Reims Cathedral

Notre-Dame de Reims (/ˌnɒtrə ˈdɑːm, ˌnoʊtrə ˈdeɪm, ˌnoʊtrə ˈdɑːm/;[2][3][4] French: [nɔtʁə dam də ʁɛ̃s] (![]()

| Reims Cathedral | |

|---|---|

| Cathedral of Our Lady of Reims | |

French: Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Reims | |

Façade, looking northeast | |

Reims Cathedral Location in France | |

| 49°15′13″N 4°2′3″E | |

| Location | Place du Cardinal Luçon, 51100 Reims, France |

| Country | |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic |

| Website | www |

| History | |

| Status | Cathedral |

| Dedication | Our Lady of Reims |

| Associated people | Clovis I |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Active |

| Architect(s) | Jean d'Orbais Jean-le-Loup Gaucher of Reims Bernard de Soissons |

| Architectural type | Church |

| Style | High Gothic |

| Years built | 1211–1345 |

| Groundbreaking | 1211 |

| Completed | 1275 |

| Specifications | |

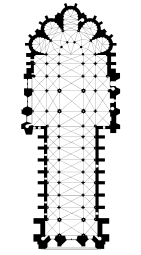

| Length | 149.17 m (489.4 ft) |

| Floor area | 6,650 m2 (71,600 sq ft) |

| Number of towers | 2 |

| Tower height | 81 m (266 ft) |

| Bells | 2 (in south tower) |

| Administration | |

| Archdiocese | Reims (Seat) |

| Clergy | |

| Archbishop | Thierry Jordan |

| Priest in charge | Jean-Pierre Laurent |

| Part of | Cathedral of Notre-Dame, Former Abbey of Saint-Rémi and Palace of Tau, Reims |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, ii, vi |

| Reference | 601-001 |

| Inscription | 1991 (15th session) |

| Official name | Cathédrale Notre-Dame |

| Designated | 1862, 1920[1] |

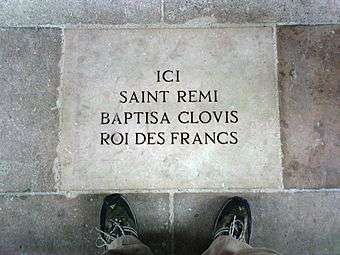

The cathedral church is thought to have been founded by Bishop Saint Nicasius in the early 5th century. Marking an important conversion, Clovis, King of the Franks, was baptized a Christian here about a century later. Construction of the present Reims Cathedral began in the 13th century and concluded in the 15th century. A prominent example of High Gothic architecture, it was built to replace an earlier church destroyed by fire in 1221. Although little damaged during the French Revolution, the present cathedral saw extensive restoration in the 19th century but was severely damaged during World War I. The church was again restored in the 20th century.

Reims Cathedral is the seat of the Archdiocese of Reims.

The cathedral, a major tourist destination, receives about one million visitors annually.[5]

History

According to Flodoard, Saint Nicasius founded the first church on the site of the current cathedral at the beginning of the 5th century,[6] probably in 401,[7] on the site of a Gallo-Roman bath.[8] The site is not far from the basilica built by Bishop Betause,[9] where Saint Nicasius was martyred by beheading either by the Vandals in 407[10] or by the Huns in 451. The dedication of the church to the Virgin Mary[6] suggests that the latter of the two dates is the correct one, given that the first church to be named after the Virgin Mary was the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore in the 430s.[9] The Reims church, measuring approximately 20 m (66 ft) by 55 m (180 ft),[11] was where Clovis, King of the Franks, was baptized by Saint Remigius on Christmas Day some time between 496 and 508.[12][13] A baptistery was built in the 6th century to the north of the current site to a plan of a square exterior and a circular interior.[10]

In 816, the Frankish emperor Louis the Pious was crowned in Reims by Pope Stephen IV.[10] The coronation and ensuing celebrations highlighted the poor condition of the church, then the seat of an archbishop.[12] Over the next decade, Archbishop Ebbo of Reims rebuilt much of the church under the direction of the royal architect Rumaud,[10] only ceasing in 846, under the episcopate of Archbishop Hincmar, who adorned the church's interior with gilding, mosaics, paintings, sculptures and tapestries.[7] On 18 October 862, in the presence of King Charles the Bald, Hincmar dedicated the new church, which measured 86 m (282 ft) and had two transepts.[14] At the beginning of the 10th century, an ancient crypt underneath the original church was rediscovered. Under Archbishop Hervé, the crypt (which had been the initial centre of the previous churches above it) was cleared, renovated, and then rededicated to Saint Remi.[10] The altar has been located above the crypt for 15 centuries.[14]

Beginning in 976, Archbishop Adalbero began to enlarge and illuminate the Carolingian cathedral.[15] The historian Richerus, a pupil of Adalbero, gives a very precise description of the work carried out by the Archbishop:[16]

"He completely destroyed the arcades which, extending from the entrance to nearly a quarter of the basilica, up to the top, so that the whole church, embellished, acquired more extent and a more suitable form (...). He decorated the main altar of the golden cross and enveloped it with a resplendent trellis (...). He lit up the same church with windows in which various stories were represented and endowed it with bells roaring like thunder."

— Richerus of Reims

On 19 May 1051, King Henry I of France and Anne of Kiev married in the cathedral.[17]

Whilst conducting the Council of Reims in 1131, Pope Innocent II anointed and crowned the future Louis VII in the cathedral.[18][19]

In the middle of the 12th century, Archbishop Samson demolished the façade and adjoining tower in order to build a new cathedral with two flanking towers, likely in imitation of the Abbey of Saint Denis in Paris, whose choir dedication Samson himself had attended a few years earlier. In addition to these works to the west of the building, a new choir and chapels began to be built east of the cathedral,[20] which measured 110 m (360 ft).[15] At the end of the century, the nave and the transept were of the Carolingian style while the chevet and façade were early Gothic.[21]

Our Lady of Reims

On 6 May 1210,[22][23] the Carolingian-early Gothic cathedral was destroyed by fire on the feast day of Saint John Before the Latin Gate, allegedly due to "carelessness."[12] Exactly one year later,[22] construction began when Archbishop Aubrey laid the first stone[15] of the new cathedral's chevet. In July 1221, the chapel of this axially-radiating chevet entered use.[23] Four architects would succeed each other until the completion of the cathedral's structural work in 1275: Jean d'Orbais, Jean-le-Loup, Gaucher of Reims and Bernard de Soissons.

Documentary records show the acquisition of land to the west of the site in 1218, suggesting the new cathedral was substantially larger than its predecessors, the lengthening of the nave presumably being an adaptation to afford room for the crowds that attended the coronations.[24] In 1233 a long-running dispute between the cathedral chapter and the townsfolk (regarding issues of taxation and legal jurisdiction) boiled over into open revolt.[25] Several clerics were killed or injured during the resulting violence and the entire cathedral chapter fled the city, leaving it under an interdict (effectively banning all public worship and sacraments).[26] Work on the new cathedral was suspended for three years, only resuming in 1236 after the clergy returned to the city and the interdict was lifted following mediation by the King and the Pope. Construction then continued more slowly. The area from the crossing eastwards was in use by 1241 but the nave was not roofed until 1299 (when the French King lifted the tax on lead used for that purpose). Work on the west façade took place in several phases, which is reflected in the very different styles of some of the sculptures. The upper parts of the façade were completed in the 14th century, but apparently following 13th-century designs, giving Reims an unusual unity of style.

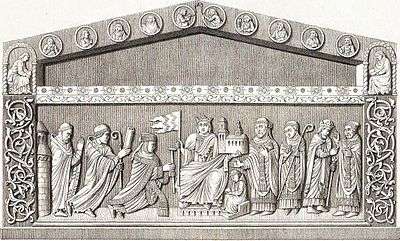

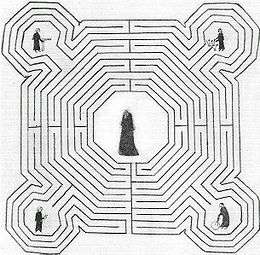

Unusually the names of the cathedral's original architects are known. A labyrinth built into floor of the nave at the time of construction or shortly after (similar to examples at Chartres and Amiens) included the names of four master masons (Jean d'Orbais, Jean-Le-Loup, Gaucher de Reims and Bernard de Soissons) and the number of years they worked there, though art historians still disagree over who was responsible for which parts of the building.[27] The labyrinth itself was destroyed in 1779 but its details and inscriptions are known from 18th-century drawings. The clear association here between a labyrinth and master masons adds weight to the argument that such patterns were an allusion to the emerging status of the architect (through their association with the mythical artificer Daedalus, who built the Labyrinth of King Minos). The cathedral also contains further evidence of the rising status of the architect in the tomb of Hugues Libergier (d. 1268, architect of the now-destroyed Reims church of St-Nicaise). Not only is he given the honour of an engraved slab; he is shown holding a miniature model of his church (an honour formerly reserved for noble donors) and wearing the academic garb befitting an intellectual.

The towers, 81 meters (266 ft) tall, were originally designed to rise 120 meters (390 ft). The south tower holds just two great bells; one of them, named “Charlotte” by Charles, Cardinal of Lorraine in 1570, weighs more than 10,000 kilograms (10 t).

Following the death of the infant King John I, his uncle Philip was hurriedly crowned at Reims, 9 January 1317.[28]

During the Hundred Years' War the cathedral and city were under siege by the English from 1359 to 1360, but the siege failed.[29] In 1380, Reims cathedral was the location of Charles VI's coronation and eight years later Charles called a council at Reims in 1388 to take personal rule from the control of his uncles.[30] After Henry V, King of England, defeated Charles VI's army at Agincourt, Reims along with most of northern France fell to the English.[31] The English held Reims and the Cathedral until 1429 when it was liberated by Joan of Arc which allowed the Dauphin Charles to be crowned king on 17 July 1429.[32] Following the death of Francis I of France, Henry II was crowned King of France on 25 July 1547 in Reims cathedral.[33]

On 24 July 1481, a new fire caused by the negligence of workers on the roof took hold in the attic, causing the destruction of the framework, central bell tower, and the galleries at the base of the roof, and caused the lead of the roof to melt, causing further damage. However, recovery was quick with Kings Charles VIII and Louis XII making donations to the Cathedral's reconstruction. In particular, they granted the Cathedral an octroi in regards to the unpopular Gabelle tax. In gratitude, the new roof was adorned by fleur-de-lis and the royal coat of arms "affixed to the top of the façade". However, this work was suspended before the arrows were completed in 1516.[34]

Although Reims was an important symbol of the French monarchy, the chaos of the French Revolution did not damage it to the same extent as at Chartres Cathedral, where the structure of the cathedral itself was threatened. Some statues were broken, the gates were torn down, and the royal Hand of Justice was burned.[35]

In 1860, Eugène Viollet-le-Duc directed the restoration of Reims Cathedral.[36] In 1875, the French National Assembly voted to allocate £80,000 for repairs of the façade and balustrades.

First World War

On the outbreak of the First World War, the cathedral was commissioned as a hospital, and troops and arms were removed from its immediate vicinity.[37][38][39] On 4 September 1914, the XII Saxon corps arrived at the city and later that day the Imperial German Army began shelling the city.[lower-alpha 2] The guns, located 7 kilometers (4.3 mi) away in Les Mesneux, ceased firing when the XII Saxon Corps sent two officers and a city employee to ask them to stop shelling the city.[42] The bombardment damaged the cathedral considerably, blowing out many windows, and damaging several statues and elements of the upper facade.[43] On 12 September, the German Army decided to place their wounded in the cathedral against the protests of Maurice Landrieux,[44] and spread 15,000 bales of straw on the floor of the cathedral for this purpose. That day, however, the town was evacuated of German soldiers before French General Franchet d'Esperey entered the city.[45] Six days later, a shell exploded in the bishop's palace, killing three and injuring 15.[46]

Scaffolding around the north tower caught fire, spreading the blaze to all parts of the timber frame superstructure. The lead in the roofing melted and poured through the stone gargoyles, destroying in turn the bishop's palace.[47] Images of the cathedral in ruins were shown during the war by the indignant French, accusing the Germans of the deliberate destruction of buildings rich in national and cultural heritage.

Restoration work began in 1919, under the direction of architect Henri Deneux, a native of Reims; the cathedral was fully reopened in 1938, thanks in part to financial support from the Rockefellers, but work has been steadily going on since.

Modern era

In 1955 Georges Saupique made a copy of "Le Couronnement de la Vierge" which can be seen above the cathedral entrance and with Louis Leygue copied many of the other sculptures on the cathedral facade. He also executed a statue of St Thomas for the north tower.

The Franco-German reconciliation was symbolically formalized in July 1962 by French president Charles de Gaulle and German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, where in 1914 the Imperial German Army deliberately shelled the cathedral in order to shake French morale.[48]

The cathedral, former Abbey of Saint-Remi, and the Palace of Tau were added to the list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites in 1991.[49]

On his 74th Pastoral Visit, Pope John Paul II visited Reims on 26 September 1996 for the 1500th anniversary of the baptism of Clovis.[50] While there, the Pope prayed at the same chapel where Jean-Baptiste de La Salle celebrated his first Mass in 1678.[51]

On 8 October 2016, a plaque bearing the names of the 31 kings crowned in Reims was placed in the Cathedral in the presence of Archbishop Thierry Jordan and Prince Louis Alphonse, Duke of Anjou, one of many pretenders to the French throne.[52]

French royal church

The prestige of the Holy Ampulla and the political power of the Archbishop of Reims resulted from King Henry I of France, who was crowned here in 1027 and permanently established Reims Cathedral as the location of the coronation of the French monarch. All but seven of France's future kings would be crowned at Reims.[lower-alpha 3]

The coronation of Charles VII in 1429 marked the reversal of the course of the Hundred Years' War, due in large part to the actions of Joan of Arc. She is memorialized at Reims Cathedral with two statues: an equestrian statue outside the church and another within the church.

Exterior

The cathedral's exterior glorifies royalty. In the center of the front facade and above the rose window is the Gallery of Kings, composed of 56 statues with a height of 4.5 meters (15 ft), with Clovis I in the center mid-baptism, Clotilde to his right, and Saint Remigius to his left.

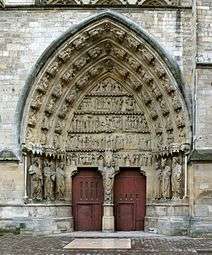

The three portals are laden with statues and statuettes; among European cathedrals, only Chartres has more sculpted figures. The central portal, dedicated to the Virgin Mary, is surmounted by a rose window framed in an arch itself decorated with statuary, in place of the usual sculptured tympanum. The "gallery of the kings" above shows the baptism of Clovis in the centre flanked by statues of his successors.

The facades of the transepts are also decorated with sculptures. That on the North has statues of bishops of Reims, a representation of the Last Judgment and a figure of Jesus (le Beau Dieu), while that on the south side has a modern rose window with the prophets and apostles. Fire destroyed the roof and the spires in 1481: of the four towers that flanked the transepts, nothing remains above the height of the roof. Above the choir rises an elegant lead-covered timber bell tower that is 18 m (about 59 feet) tall, reconstructed in the 15th century and in the 1920s. The total exterior length is 149.17 meters and its surface area is 6,650 square meters.

Interior

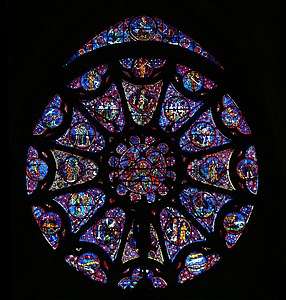

The interior of the cathedral is 138.75 m (about 455 ft) long, 30 m (approx. 98 feet) wide in the nave, and 38 m (about 125 feet) high in the centre. It comprises a nave with aisles, transepts with aisles, a choir with double aisles, and an apse with ambulatory and radiating chapels. It has interesting stained glass ranging from the 13th to the 20th century. The rose window over the main portal and the gallery beneath are of rare magnificence.

The cathedral possesses fine tapestries. Of these the most important series is that presented by Robert de Lenoncourt, archbishop under François I (1515–1547), representing the life of the Virgin. They are now to be seen in the former bishop's palace, the Palace of Tau. The north transept contains a fine organ in a flamboyant Gothic case. The choir clock is ornamented with curious mechanical figures. Marc Chagall designed the stained glass installed in 1974 in the axis of the apse.

The treasury, kept in the Palace of Tau, includes many precious objects, among which is the Sainte Ampoule, or holy flask, the successor of the ancient one that contained the oil with which French kings were anointed, which was broken during the French Revolution, a fragment of which the present Ampoule contains.

800th anniversary

In 2011, the city of Reims celebrated the cathedral's 800th anniversary. The celebrations ran from 6 May to 23 October. Concerts, street performances, exhibitions, conferences, and a series of evening light shows highlighted the cathedral and its 800th anniversary. In addition, six new stained glass windows designed by Imi Knoebel, a German artist, were inaugurated on June 25, 2011. The six windows cover an area of 128 square meters (1,380 sq ft) and are positioned on both sides of the Chagall windows in the apse of the cathedral.

Gallery

%2C_Die_Kathedrale_von_Reims.jpg) The Cathedral of Reims, by Domenico Quaglio the Younger

The Cathedral of Reims, by Domenico Quaglio the Younger The first German shell bursts on the cathedral during the First World War

The first German shell bursts on the cathedral during the First World War Reims Cathedral burning during World War I (retouched photograph)

Reims Cathedral burning during World War I (retouched photograph) North tower

North tower- Rose windows, west end

Interior view, west rose

Interior view, west rose Organ

Organ Central altar

Central altar Stained-glass at the west end of the northern aisle

Stained-glass at the west end of the northern aisle- The Cathedral of Reims at night Rêve de couleurs

Above the choir

Above the choir North transept

North transept- Axial chapel stained glass windows designed by Marc Chagall, 1974

Roof details

Roof details- Support structure of the roof

Paving stone in cathedral nave commemorating baptism of Clovis by Saint Remi

Paving stone in cathedral nave commemorating baptism of Clovis by Saint Remi Main gate

Main gate Side portal (north)

Side portal (north) Golden eagle

Golden eagle Interior of the cathedral

Interior of the cathedral Cathedral diagram

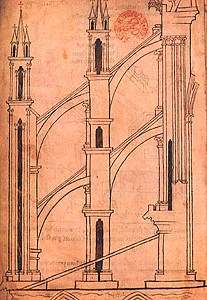

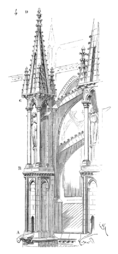

Cathedral diagram Villard de Honnecourt's drawing of a flying buttress at Reims, ca. 1230s (Bibliothèque nationale)

Villard de Honnecourt's drawing of a flying buttress at Reims, ca. 1230s (Bibliothèque nationale)

Architectural details depicting Horse Chestnut tree leaves

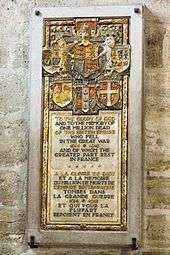

Architectural details depicting Horse Chestnut tree leaves Marker in memory of World War I

Marker in memory of World War I

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Reims. |

Notes

Footnotes

- The name Notre Dame, meaning "Our Lady" was frequently used in names of churches including the cathedrals in France.

- According to Maurice Landrieux, then Bishop of Dijon, the German shelling began an hour after he had finished that Friday's sermon. A white flag was said by Bishop Landrieux to have mounted from the north tower of the cathedral by the vicar and an M. Rouné.[40] This flag remained at the top of the tower through the short German occupation of the city and was replaced with the French tricolor on 12 September 1914.[41]

- Exceptions: Hugh Capet, Robert II, Louis VI, John I, Henry IV, Louis XVIII, and Louis Philippe I.

Citations

- French Ministry of Culture: Cathédrale Notre-Dame.

- Collins Dictionary: "Notre Dame".

- Oxford English Dictionary: "Notre Dame".

- New Oxford American Dictionary: "Notre Dame".

- Reims Cathedral page on culture.fr.

- Sadler 2017, p. 17.

- Bourassé 1872, p. 45.

- Demouy 1995, pp. 11.

- Demouy 1995, p. 10.

- Lambert 1959, p. 244.

- Demouy 1995, pp. 11–12.

- Demouy 2011, p. 9.

- Bordonove 1988, p. 97.

- Demouy 1995, p. 12.

- Demouy 1995, p. 14.

- Barral i Altet 1987, p. 105.

- McLaughlin 2010, p. 56.

- Robinson 1990, pp. 22, 135.

- Brown 1992, p. 43.

- Lambert 1959, p. 224.

- Demouy 2011, p. 10.

- Branner 1961, p. 23.

- Lillich 2011, p. 1.

- For detailed chronology of rebuilding see P. Frankl / P. Crossley, Gothic Architecture, Yale University Press, 2001 (Revised Ed.), p. 322 notes 10–14.

- Raguin, Brush & Draper 1995, pp. 214–35.

- Branner 1961, p. 36.

- Branner 1962, pp. 18–25.

- Jordan 2005, p. 69.

- Prestwich 1999, p. 301.

- Sumption 2009, pp. 397, 665–66.

- Santosuosso 2004, pp. 245–46.

- Tucker 2010, pp. 333, 335.

- Thevet 2010, pp. 24–25.

- Demouy 1995, p. 20.

- Souchal 1993, pp. 61, 68.

- Auzas 1982, p. 158.

- New York Times, 4 December 2015.

- "Reims Cathedral Burns". 2014-09-19. Retrieved 2018-04-17.

- Peace Palace Library: The Destruction of the Cathedral of Reims, 1914.

- Landrieux 1920, pp. 11–12.

- Landrieux 1920, p. 26.

- Landrieux 1920, p. 13.

- Landrieux 1920, pp. 14–17.

- Landrieux 1920, p. 22.

- Landrieux 1920, pp. 23–24.

- Landrieux 1920, p. 28.

- Western Front Virtual Tour: Stop 40, Reims Cathedral.

- Auzias & Labourdette 2011, p. 14.

- UNESCO: Reims.

- Diblik 1998, p. 7.

- DLS Foot: Reims Cathedral.

- L'Union, 8 October 2016.

References

English-language references

- Branner, Robert (January 1961). "Historical Aspects of the Reconstruction of Reims Cathedral, 1210–1241". Speculum. 36 (1): 23–37. doi:10.2307/2849842. JSTOR 2849842.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Branner, Robert (1962). "The Labyrinth of Reims Cathedral". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 21: 18–25. doi:10.2307/988130. JSTOR 988130.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brown, Elizabeth A. R. (1992). "Franks, Burgundians, and Aquitanians" and the Royal Coronation Ceremony in France. The American Philosophical Society. ISBN 978-0871698278.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jordan, William Chester (2005). Unceasing Strife, Unending Fear: Jacques de Therines and the Freedom of the Church in the Age of the Last Capetians. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691121208.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Landrieux, Maurice (1920). The Cathedral of Reims: The Story of a German Crime. K. Paul, Trench, Trubner & Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lillich, Meredith Parsons (2011). The Gothic Stained Glass of Reims Cathedral. Penn State University Press. ISBN 978-0271037776.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McLaughlin, Megan (2010). Sex, Gender, and Episcopal Authority in an Age of Reform, 1000–1122. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521870054.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Prestwich, Michael (1999). Armies and Warfare in the Middle Ages: The English Experience. Yale University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Raguin, Virginia Chieffo; Brush, Kathryn; Draper, Peter (1995). Artistic Integration in Early Gothic Churches. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9780802074775.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Robinson, I. S. (1990). The Papacy, 1073–1198: Continuity and Innovation. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139167772.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sadler, Donna L. (2017). Reading the Reverse of Façade of Reims: Royalty and Ritual in Thirteenth-Century France. Routledge. ISBN 978-1351552165.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Santosuosso, Antonio (2004). Barbarians, Marauders, and Infidels. MJF Books. ISBN 978-0813391533.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sumption, Jonathan (2009). The Hundred Years War: Divided Houses. III. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780571138975.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thevet, André (2010). Benson, Edward; Schlesinger, Roger (eds.). Portraits from the French Renaissance and the Wars of Religion. Truman State University Press. ISBN 9781931112987.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2010). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-672-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

French-language references

- Auzias, Dominique; Labourdette, Jean-Paul (2011). Le Petit Futé Champagne-Ardenne. Le Petit Futé. ISBN 978-2746935181.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Baillat, Gilles (1990). Reims. Bonneton.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Barral i Altet, Xavier (1987). Le Paysage monumental de la France autour de l'an mil: avec un appendice Catalogne. Picard. ISBN 2708403370.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bordonove, Georges (1988). Clovis et les Mérovingiens. Pygmalion. ISBN 2857042825.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bourassé, Jean-Jacques (1872). Les plus belles cathédrales de France. A. Mame et fils.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Demouy, Patrick (1995). Notre-Dame de Reims : Sanctuaire de la monarchie sacrée. CNRS Éditions. ISBN 2-271-05258-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Demouy, Patrick (May 2011). "Genèse d'une cathédrale royale". Historia.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Diblik, Jean (1998). Reims: Comment lire une cathédrale. Editions d'art et d'histoire ARHIS. ISBN 2906755133.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lambert, Élie (1959). "La cathédrale de Reims et les cathédrales qui l'ont précédée sur le même emplacement". Comptes-rendus des Séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. 103 (2): 241–250. doi:10.3406/crai.1959.11054.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Souchal, François (1993). Le Vandalisme de la Révolution. Nouvelles Éditions latines. ISBN 9782723304764.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Theis, Laurent (1996). Clovis de l'histoire au mythe. Complexe. ISBN 2870276192.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Auzas, Pierre-Marie (1982). Actes du Colloque international Viollet-le-Duc, Paris, 1980. Nouvelles Éditions latines. ISBN 9782723301763.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

News sources

- Rubin, Richard (4 December 2015). "The Legend and Lore of Notre-Dame de Reims". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- Coulet, Valérie (8 October 2016). "Des "Vive le roi!" résonnent dans la cathédrale de Reims". L'Union (in French). Retrieved 8 October 2016.

Online references

- "Notre Dame". Collins English Dictionary. Archived from the original on 16 October 2018. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- "Notre Dame". Oxford English Dictionary. Archived from the original on 15 April 2019. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- "Notre Dame". New Oxford American Dictionary. Archived from the original on 15 April 2019. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- "Cathedral of Notre-Dame, Former Abbey of Saint-Rémi and Palace of Tau, Reims". United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization.

- "In the Footsteps of De La Salle". The Brothers of the Christian Schools.

- "Cathédrale Notre-Dame". culture.gouv.fr (in French). Monument historique. 29 March 1993.

- "The Destruction of the Cathedral of Reims". Peace Palace Library. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- Worcester, Kimball (2014-10-17). "Western Front Virtual Tour — Stop 40: Reims Cathedral". roadstothegreatwar-ww1.blogspot.com. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

See also

- High Gothic

- French Gothic architecture

- Gothic architecture

- List of Gothic Cathedrals in Europe

External links

- (in French) Official website

- Reims Cathedral on French cultural website (culture.fr)

- Reims Cathedral at archINFORM

- Photographs of Reims at kunsthistorie.com

- 360 degrees panoramas

- Poems by Florence Earle Coates: "Rheims", "The Smile of Reims"