Classificatory disputes about art

Art historians and philosophers of art have long had classificatory disputes about art regarding whether a particular cultural form or piece of work should be classified as art. Disputes about what does and does not count as art continue to occur today.[1]

Definitions of art

Defining art can be difficult. Aestheticians and art philosophers often engage in disputes about how to define art. By its original and broadest definition, art (from the Latin ars, meaning "skill" or "craft") is the product or process of the effective application of a body of knowledge, most often using a set of skills; this meaning is preserved in such phrases as "liberal arts" and "martial arts". However, in the modern use of the word, which rose to prominence after 1750, “art” is commonly understood to be skill used to produce an aesthetic result (Hatcher, 1999).

Britannica Online defines it as "the use of skill or imagination in the creation of aesthetic objects, environments, or experiences that can be shared with others".[2] But how best to define the term “art” today is a subject of much contention; many books and journal articles have been published arguing over even the basics of what we mean by the term “art” (Davies, 1991 and Carroll, 2000). Theodor Adorno claimed in 1969 “It is self-evident that nothing concerning art is self-evident any more.” It is not clear who has the right to define art. Artists, philosophers, anthropologists, and psychologists all use the notion of art in their respective fields, and give it operational definitions that are not very similar to each other's.

The second, more narrow, more recent sense of the word “art” is roughly as an abbreviation for creative art or “fine art.” Here we mean that skill is being used to express the artist’s creativity, or to engage the audience’s aesthetic sensibilities. Often, if the skill is being used to create objects with a practical use, rather than paintings or sculpture with no practical function other than as an artwork, it will be considered it as falling under classifications such as the decorative arts, applied art and craft rather than fine art. Likewise, if the skill is being used in a commercial or industrial way, it will be considered design instead of art. Some thinkers have argued that the difference between fine art and applied art has more to do with value judgments made about the art than any clear definitional difference (Novitz, 1992). The modern distinction does not work well for older periods, such as medieval art, where the most highly regarded art media at the time were often metalwork, engraved gems, textiles and other "applied arts", and the perceived value of artworks often reflected the cost of the materials and sheer amount of time spent creating the work at least as much as the creative input of the artist.

Schemes of classification of arts

Historical schemes

In the Zhou dynasty of ancient China, excellence in the liù yì (六藝), or "Six Arts", was expected of the junzi (君子), or "perfect gentleman", as defined by philosophers like Confucius. Because these arts spanned both the civil and military aspects of life, excelling in all six required a scholar to be very well-rounded and polymathic. The Six Arts were as follows:

- Rites (禮)

- Music (樂)

- Archery (射)

- Charioteering and equestrianism (御)

- Calligraphy (書)

- Mathematics (數)

Later in the history of imperial China, the Six Arts were pared down, creating a similar system of Four Arts for the scholar-official caste to learn and follow:

- Qín (琴), an instrument representing music

- Qí (棋), a board game representing military strategy

- Shū (書), or Chinese calligraphy, representing literacy

- Huà (畫), or Chinese painting, representing the visual arts

Another attempt to systematically define art as a grouping of disciplines in antiquity is represented by the ancient Greek Muses. Each of the standard nine Muses symbolized and embodied one of nine branches of what the Greeks called techne, a term which roughly means "art" but has also been translated as "craft" or "craftsmanship", and the definition of the word also included more scientific disciplines. These nine traditional branches were:

- Epic poetry, embodied by Calliope

- History, embodied by Clio

- Music and lyric poetry, embodied by Euterpe

- Love poetry, embodied by Erato

- Tragedy, embodied by Melpomene

- Hymns and pantomime, embodied by Polyhymnia

- Dance and chorus, embodied by Terpsichore

- Comedy and idyllic poetry, embodied by Thalia

- Astronomy, embodied by Urania

In medieval Christian Europe, universities taught a standard set of seven liberal arts, defined by early medieval philosophers such as Boethius and Alcuin of York and as such centered around philosophy. The definitions of these subjects and their practice was heavily based on the educational system of Greece and Rome. These seven arts were themselves split into two categories:

- the Trivium, considered the foundation of knowledge, and comprising the three basic elements of philosophy: grammar, logic, and rhetoric;

- and the Quadrivium, comprising music, arithmetic, geometry and astronomy.

At this time, and continuing after the Renaissance, the word "art" in English and its cognates in other languages had not yet attained their modern meaning. One of the first philosophers to discuss art in the framework we understand today was Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, who described in his Lectures on Aesthetics a ranking of the five major arts from most material to most expressive:

Hegel's listing of the arts caught on particularly in France, and with continual modifications the list has remained relevant and a subject of debate in French culture into the 21st century. This classification was popularized by Ricciotto Canudo, an early scholar of film who wrote "Manifesto of the Seventh Art" in 1923. The epithets given to each discipline by its placement of the list are often used to refer to them through paraphrase, particularly with calling film "the seventh art". The French Ministry of Culture often participates in the decision making for defining a "new" art.[3] The ten arts are generally given as follows:

- le premier art: architecture

- le deuxième art: sculpture

- le troisième art: painting

- le quatrième art: music

- le cinquième art: literature, including poetry and prose

- le sixième art: the performing arts, including dance and theatre

- le septième art: film and cinema

- le huitième art: "les arts médiatiques", including radio, television, and photography

- le neuvième art: comics

- le dixième art: video games, or digital art forms more generally[4]

The ongoing dispute over what should constitute the next form of art has been fought for over a century. Currently, there are a variety of contenders for le onzième art, many of which are older disciplines whose practitioners feel that their medium is underappreciated as art. One particularly popular contender for the 11th is multimedia, which is intended to bring together the ten arts just as Canudo argued that cinema was the culmination of the first six arts. Performance art, as separate from the performing arts, has been called le douzième, or "twelfth", art.[5]

Generalized definitions of art

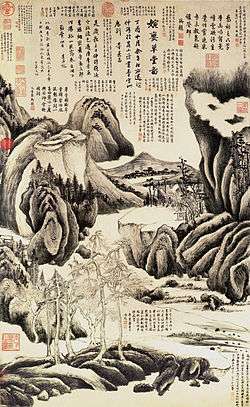

The traditional Western classifications since the Renaissance have been variants of the hierarchy of genres based on the degree to which the work displays the imaginative input of the artist, using artistic theory that goes back to the ancient world. Such thinking received something of a boost with the aesthetics of Romanticism. A similar theoretical framework applied in traditional Chinese art; for example in both the Western and Far Eastern traditions of landscape painting (see literati painting), imaginary landscapes were accorded a higher status than realistic depictions of an actual landscape view - in the West relegated to "topographical views".

Many have argued that it is a mistake to even try to define art or beauty, that they have no essence, and so can have no definition. Often, it is said that art is a cluster of related concepts rather than a single concept. Examples of this approach include Morris Weitz and Berys Gaut.

Another approach is to say that “art” is basically a sociological category, that whatever art schools and museums, and artists get away with is considered art regardless of formal definitions. This institutional theory of art has been championed by George Dickie. Most people did not consider a store-bought urinal or a sculptural depiction of a Brillo Box to be art until Marcel Duchamp and Andy Warhol (respectively) placed them in the context of art (i.e., the art gallery), which then provided the association of these objects with the values that define art.

Proceduralists often suggest that it is the process by which a work of art is created or viewed that makes it, art, not any inherent feature of an object, or how well received it is by the institutions of the art world after its introduction to society at large. For John Dewey, for instance, if the writer intended a piece to be a poem, it is one whether other poets acknowledge it or not. Whereas if exactly the same set of words was written by a journalist, intending them as shorthand notes to help him write a longer article later, these would not be a poem.

Leo Tolstoy, on the other hand, claims that what makes something art or not is how it is experienced by its audience, not by the intention of its creator.[6] Functionalists, like Monroe Beardsley argue that whether a piece counts as art depends on what function it plays in a particular context. For instance, the same Greek vase may play a non-artistic function in one context (carrying wine), and an artistic function in another context (helping us to appreciate the beauty of the human figure).

Disputes about classifying art

Philosopher David Novitz has argued that disagreements about the definition of art are rarely the heart of the problem, rather that “the passionate concerns and interests that humans vest in their social life” are “so much a part of all classificatory disputes about art” (Novitz, 1996). According to Novitz, classificatory disputes are more often disputes about our values and where we are trying to go with our society than they are about theory proper. For example, when the Daily Mail criticized Damien Hirst and Tracey Emin’s work by arguing "For 1,000 years art has been one of our great civilising forces. Today, pickled sheep and soiled beds threaten to make barbarians of us all" they are not advancing a definition or theory about art, but questioning the value of Hirst’s and Emin’s work.

On the other hand, Thierry de Duve[7] argues that disputes about the definition of art are a necessary consequence of Marcel Duchamp's presentation of a readymade as a work of art. In his 1996 book Kant After Duchamp he reinterprets Kant's Critique of Judgement exchanging the phrase "this is beautiful" with "this is art", using Kantian aesthetics to address post-Duchampian art.

Conceptual art

The work of the French artist Marcel Duchamp from the 1910s and 1920s paved the way for the conceptualists, providing them with examples of prototypically conceptual works (the readymades, for instance) that defied previous categorisations. Conceptual art emerged as a movement during the 1960s. The first wave of the "conceptual art" movement extended from approximately 1967 to 1978. Early "concept" artists like Henry Flynt, Robert Morris and Ray Johnson influenced the later, widely accepted movement of conceptual artists like Dan Graham, Hans Haacke, and Douglas Huebler.

More recently, the “Young British Artists” (YBAs), led by Damien Hirst, came to prominence in the 1990s and their work is seen as conceptual, even though it relies very heavily on the art object to make its impact. The term is used in relation to them on the basis that the object is not the artwork, or is often a found object, which has not needed artistic skill in its production. Tracey Emin is seen as a leading YBA and a conceptual artist, even though she has denied that she is and has emphasised personal emotional expression.

Recent examples of disputed conceptual art

1991

Charles Saatchi funds Damien Hirst. The following year, the Saatchi Gallery exhibits Hirst's The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, a shark in formaldehyde in a vitrine.

1993

Vanessa Beecroft holds a performance in Milan, Italy. Here, young girls act as a second audience to the display of her diary of food.

1999

Tracey Emin is nominated for the Turner Prize. My Bed consisted of her disheveled bed, surrounded by detritus such as condoms, blood-stained knickers, bottles and her bedroom slippers.

2001

Martin Creed wins the Turner Prize for accurately titled The Lights Going On and Off, in which lights turned on and off in an otherwise empty room.[8]

2002

Miltos Manetas confronts the Whitney Biennial with his Whitneybiennial.com.[9]

2005

Simon Starling wins the Turner Prize for Shedboatshed. Starling presented a wooden shed which he had converted into a boat, floated down the Rhine, then remade into a shed..[10]

Controversy in the UK

.jpg)

The Stuckist group of artists, founded in 1999, proclaimed themselves "pro-contemporary figurative painting with ideas and anti-conceptual art, mainly because of its lack of concepts." They also called it pretentious, "unremarkable and boring" and on July 25, 2002, in a demonstration, deposited a coffin outside the White Cube gallery, marked "The Death of Conceptual Art".[11][12] In 2003, the Stuckism International Gallery exhibited a preserved shark under the title A Dead Shark Isn't Art, clearly referencing the Damien Hirst work (see disputes above).[13]

In a BBC2 Newsnight programme on 19 October 1999 hosted by Jeremy Paxman with Charles Thomson attacking that year's Turner Prize and artist Brad Lochore defending it, Thomson was displaying Stuckist paintings, while Lochore had brought along a plastic detergent bottle on a cardboard plinth. At one stage Lochore states, "if people say it's art, it's art". Paxman asks, "So you can say anything is art?" and Lochore replies, "You could say everything is art..." At this point Thomson, off-screen, can be heard to say, "Is my shoe art?" while at the same time his shoe appears in front of Lochore, who observes, "If you say it is. I have to judge it on those terms." Thomson's response is, "I've never heard anything so ludicrous in my life before."[14]

In 2002, Ivan Massow, the Chairman of the Institute of Contemporary Arts branded conceptual art "pretentious, self-indulgent, craftless tat" and in "danger of disappearing up its own arse ... led by cultural tsars such as the Tate's Sir Nicholas Serota".[15] Massow was consequently forced to resign. At the end of the year, the Culture Minister, Kim Howells, an art school graduate, denounced the Turner Prize as "cold, mechanical, conceptual bullshit".[16]

In October 2004, the Saatchi Gallery told the media that "painting continues to be the most relevant and vital way that artists choose to communicate."[17] Following this, Charles Saatchi began to sell prominent works from his YBA (Young British Artists) collection.

Computer and video games

Computer games date back as far as 1947, although they did not reach much of an audience until the 1970s. It would be difficult and odd to deny that computer and video games include many kinds of art (bearing in mind, of course, that the concept "art" itself is, as indicated, open to a variety of definitions). The graphics of a video game constitute digital art, graphic art, and probably video art; the original soundtrack of a video game clearly constitutes music. However it is a point of debate whether the video game as a whole should be considered a piece of art of some kind, perhaps a form of interactive art.

Film critic Roger Ebert, for example, has gone on record claiming that video games are not art, and for structural reasons will always be inferior to cinema, but then, he admits his lack of knowledge in the area when he affirmed that he "will never play a game when there is a good book to be read or a good movie to be watched.".[18] Video game designer Hideo Kojima has argued that playing a videogame is not art, but games do have artistic style and incorporate art.[19][20][21] Video game designer Chris Crawford argues that video games are art.[22] Esquire columnist Chuck Klosterman also argues that video games are art.[23] Tadhg Kelly argues that play itself is not art and that fun is a constant required for all games [24] so the art in games is the art of location and place rather than interaction.[25]

See also

Notes and references

- Semiotics of the Media By Winfried Nöth

- Britannica Online

- Crampton, Thomas. "For France, Video Games Are as Artful as Cinema", The New York Times, November 6, 2006.

- "Connaissez-vous le 10eme art ? L'art numérique.", 2007.

- Mas, Jean. Manifeste de la Performance, AICA-France/Villa Arson, 2012.

- Tolstoy, Leo, graf, 1828-1910. (1996). What is art?. Maude, Aylmer, 1858-1938. Indianapolis: Hackett Pub. Co. ISBN 087220295X. OCLC 36716419.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Thierry de Duve, Kant After Duchamp. 1996

- BBC Online

- Mirapaul, Matthew (4 March 2002). "ARTS ONLINE; If You Can't Join 'Em, You Can Always Tweak 'Em". The New York Times.

- The Times

- Cripps, Charlotte. "Visual arts: Saying knickers to Sir Nicholas, The Independent, 7 September 2004. Retrieved from findarticles.com, 7 April 2008. Archived 5 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- "White Cube demo 2002" stuckism.com. Retrieved 25 May 2008.

- Alberge, Dalya. "Traditionalists mark shark attack on Hirst", The Times, 10 April 2003. Retrieved 6 February 2008.

- Milner, Frank, ed. The Stuckists Punk Victorian, pp.32-48, National Museums Liverpool 2004, ISBN 1-902700-27-9.

- The Guardian

- The Daily Telegraph

- Reynolds, Nigel 2004 "Saatchi's latest shock for the art world is – painting" The Daily Telegraph 10 February 2004. Accessed April 15, 2006

- "Why did the chicken cross the genders?". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on 2010-06-19.

- "Official PlayStation Magazine (US)". Feb 2006. 2006. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-10-17. Retrieved 2011-08-01.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- A videogame is not art!

- Chris Crawford, The Art of Computer Game Design 1982 mirrored with permission at Archived 2010-06-12 at the Wayback Machine

- Chuck Klosterman “The Lester Bangs of Video Games” Esquire July 2006 at

- Tadhg Kelly, Fun: Simple to Explain, Hard to Accept, 2011, at

- Tadhg Kelly, Living Galleries, 2011 at

Further reading

- Noel Carroll, Theories of Art Today. 2000

- Thierry de Duve, Kant After Duchamp. 1996

- Evelyn Hatcher, ed. Art as Culture: An Introduction to the Anthropology of Art. 1999

- David Novitz, ’’Disputes about Art’’ Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 54:2, Spring 1996

- Nina Felshin, ed. But is it Art? 1995

- David Novitz, The Boundaries of Art. 1992

- Stephen Davies, Definitions of Art. 1991

- Leo Tolstoy, What Is Art?