Mirror

A mirror or reflector is an object such that each narrow beam of light that incides on its surface bounces (is reflected) in a single direction. This property, called specular reflection, distinguishes a mirror from objects that scatter light in many directions (such as flat-white paint), let it pass through them (such as a lens or prism), or absorb it.

Most mirrors behave as such only for certain ranges of wavelength, direction, and polarization of the incident light; most commonly for visible light, but also for other regions of the electromagnetic spectrum from X-rays to radio waves. A mirror will generally reflect only a fraction of the incident light; even the best mirrors may scatter, absorb, or transmit a small portion of it. If the mirror's width is only a few times the wavelength of the light, a significant part of the light will also be diffracted instead. An object that is a mirror when examined at a small scale (like a bearing ball) may seem to be scattering light when examined at a larger scale.

When looking at a mirror, one will see a mirror image or reflected image of objects in the environment, formed by light emitted or scattered by them and reflected by the mirror towards one's eyes. This effect gives the illusion that those objects are behind the mirror, or (sometimes) in front of it. A plane mirror will yield a real-looking undistorted image, while a curved mirror may distort, magnify, or reduce the image in various ways.

A mirror is commonly used for inspecting oneself, such as during personal grooming; hence the old-fashioned name looking glass.[1] This use, which dates from the Prehistory,[2] overlaps with uses in decoration and architecture. Mirrors are also used to view other items that are not directly visible because of obstructions; examples include rear-view mirrors in vehicles, security mirrors in or around buildings, and dentist's mirrors. Mirrors are also used in optical and scientific apparatus such as telescopes, lasers, cameras, periscopes, and industrial machinery.

The terms "mirror" and "reflector" can be used for devices that reflect other types of radiation according to the same laws. An acoustic mirror reflects sound waves, and may be used for applications such as directional microphones, atmospheric studies, sonar, and sea floor mapping.[3] An atomic mirror reflects matter waves, and can be used for atomic interferometry and atomic holography.

History

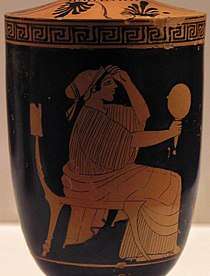

Right: seated woman holding a mirror; Ancient Greek Attic red-figure lekythos by the Sabouroff Painter, c. 470–460 BC, National Archaeological Museum, Athens (Greece)

.jpg)

Prehistory

The first mirrors used by humans were most likely pools of dark, still water, or water collected in a primitive vessel of some sort. The requirements for making a good mirror are a surface with a very high degree of flatness (preferably but not necessarily with high reflectivity), and a surface roughness smaller than the wavelength of the light.

The earliest manufactured mirrors were pieces of polished stone such as obsidian, a naturally occurring volcanic glass.[4] Examples of obsidian mirrors found in Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) have been dated to around 6000 BC.[5] Mirrors of polished copper were crafted in Mesopotamia from 4000 BC,[5] and in ancient Egypt from around 3000 BC.[6] Polished stone mirrors from Central and South America date from around 2000 BC onwards.[5]

Bronze Age to Early Middle Age

By the Bronze Age most cultures were using mirrors made from polished discs of bronze, copper, silver, or other metals.[4][7] In China, bronze mirrors were manufactured from around 2000 BC, some of the earliest bronze and copper examples being produced by the Qijia culture. Such metal mirrors remained the norm through to Greco-Roman Antiquity and throughout the Middle Ages in Europe.[8] During the Roman Empire silver mirrors were in wide use even by maidservants.[9]

Speculum metal is a highly reflective alloy of copper and tin that has been used for mirrors until a couple of centuries ago. Such mirrors may have originated in China and India.[10] Mirrors of speculum metal or any precious metal were hard to produce and were only owned by the wealthy.[11]

Common metal mirrors tarnished and required frequent polishing. Bronze mirrors had low reflectivity and poor color rendering, and stone mirrors were much worse in this regard.[12]:p.11 These defects explain the New Testament reference in 1 Corinthians 13 to seeing "as in a mirror, darkly."

The Greek philosopher Socrates, of "know thyself" fame, urged young people to look at themselves in mirrors so that, if they were beautiful, they would become worthy of their beauty, and if they were ugly, they would know how to hide their disgrace through learning.[12]:p.106

Glass began to be used for mirrors in the 1st century CE, with the development of soda-lime glass and glass blowing.[13] The Roman scholar Pliny the Elder claims that artisans in Sidon (modern-day Lebanon) were producing glass mirrors coated with lead or gold leaf in the back. The metal provided good reflectivity, and the glass provided a smooth surface and protected the metal from scrathes and tarnishing.[14][15][16][12]:p.12[17] However, there is no archeological evidence of glass mirrors before the third century.[18]

These early glass mirrors were made by blowing a glass bubble, and then cutting off a small circular section from 10 to 20 cm in diameter. Their surface was either concave or convex, and imperfections tended to distort the image. Lead-coated mirrors were very thin to prevent cracking by the heat of the molten metal.[12]:p.10 Due to their poor quality, high cost, and small size, solid-metal mirrors, primarily of steel, remained in common use until the late nineteenth century.[12]:p.13

Silver-coated metal mirrors were developed in China as early as 500 CE. The bare metal was coated with an amalgam, then heated it until the mercury boiled away.[19]

Middle Ages and Renaissance

The evolution of glass mirrors in the Middle Ages followed improvements in glassmaking technology. Glassmakers in France made flat glass plates by blowing glass bubbles, spinning them rapidly to flatten them, and cutting rectangles out of them. A better method, developed in Germany and perfected in Venice by the 16th century, was to blow a cylinder of glass, cut off the ends, slice it along its length, and unroll it onto a flat hot plate.[12]:p.11 Venetian glassmakers also adopted lead glass for mirrors, because of its crystal-clarity and its easier workability. By the 11th century, glass mirrors were being produced in Moorish Spain.[20]

During the early European Renaissance, a fire-gilding technique developed to produce an even and highly reflective tin coating for glass mirrors. The back of the glass was coated with a tin-mercury amalgam, and the mercury was then evaporated by heating the piece. This process caused less thermal shock to the glass than the older molten-lead method.[12]:p.16 The date and location of the discovery is unknown, but by the 16th century Venice was a center of mirror production using this technique. These Venetian mirrors were up to 40 inches (100 cm) square.

For a century, Venice retained the monopoly of the tin amalgam technique. Venetian mirrors in richly decorated frames served as luxury decorations for palaces throughout Europe, and were very expensive. For example, in the late seventeenth century, the Countess de Fiesque was reported to have traded an entire wheat farm for a mirror, considering it a bargain.[21] However, by the end of that century the secret was leaked through to industrial espionage. French workshops succeeded in large-scale industrialization of the process, eventually making mirrors affordable to the masses, in spite of the toxicity of mercury's vapor.[22]

Industrial Revolution

The invention of the ribbon machine in the late Industrial Revolution allowed modern glass panes to be produced in bulk.[12] The Saint-Gobain factory, founded by royal initiative in France, was an important manufacturer, and Bohemian and German glass, often rather cheaper, was also important.

The invention of the silvered-glass mirror is credited to German chemist Justus von Liebig in 1835.[23] His wet deposition process involved the deposition of a thin layer of metallic silver onto glass through the chemical reduction of silver nitrate. This silvering process was adapted for mass manufacturing and led to the greater availability of affordable mirrors.

Contemporary technologies

Currently mirrors are often produced by the wet deposition of silver, or sometimes nickel or chromium (the latter used most often in automotive mirrors) via electroplating directly onto the glass substrate.[24]

Glass mirrors for optical instruments are usually produced by vacuum deposition methods. These techniques can be traced to observations in the 1920s and 1930s that metal was being ejected from electrodes in gas discharge lamps and condensed on the glass walls forming a mirror-like coating. The phenomenon, called sputtering, was developed into an industrial metal-coating method with the development of semiconductor technology in the 1970s.

A similar phenomenon had been observed with incandescent light bulbs: the metal in the hot filament would slowly sublimate and condense on the bulb's walls. This phenomenon was developed into the method of evaporation coating by Pohl and Pringsheim in 1912. John D. Strong used evaporation coating to make the first aluminum-coated telescope mirrors in the 1930s.[25] The first dielectric mirror was created in 1937 by Auwarter using evaporated rhodium.[13]

The metal coating of glass mirrors is usually protected from abrasion and corrosion by a layer of paint applied over it. Mirrors for optical instruments often have the metal layer on the front face, so that the light does not have to cross the glass twice. In these mirrors, the metal may be protected by a thin transparent coating of anon-metallic (dielectric) material. The first metallic mirror to be enhanced with a dielectric coating of silicon dioxide was created by Hass in 1937. In 1939 at the Schott Glass company, Walter Geffcken invented the first dielectric mirrors to use multilayer coatings.[13]

Burning mirrors

The Greek in Classical Antiquity were familiar with the use of mirrors to concentrate light. Parabolic mirrors were described and studied by the mathematician Diocles in his work On Burning Mirrors.[26] Ptolemy conducted a number of experiments with curved polished iron mirrors,[2]:p.64 and discussed plane, convex spherical, and concave spherical mirrors in his Optics.[27]

Parabolic mirrors were also described by the Caliphate mathematician Ibn Sahl in the tenth century.[28] The scholar Ibn al-Haytham discussed concave and convex mirrors in both cylindrical and spherical geometries,[29] carried out a number of experiments with mirrors, and solved the problem of finding the point on a convex mirror at which a ray coming from one point is reflected to another point.[30]

Types of mirrors

Mirrors can be classified in many ways; including by shape, support and reflective materials, manufacturing methods, and intended application.

By shape

Typical mirror shapes are planar, convex, and concave.

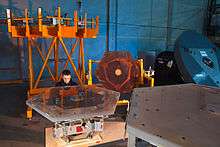

The surface of curved mirrors is often a part of a sphere, for ease of fabrication. Mirrors that are meant to precisely concentrate parallel rays of light into a point are usually made in the shape of a paraboloid of revolution instead; they are used in telescopes (form radio waves to X-rays), in antennas to communicate with broadcast satellites, and in solar furnaces. A segmented mirror, consisting of multiple flat or curved mirrors, properly placed and oriented, may be used instead.

Mirrors that are intended to concentrate sunlight onto a long pipe may be a circular cylinder or of a parabolic cylinder.

By structural material

Jan2007.jpg)

The most common structural material for mirrors is glass, due to its transparency, ease of fabrication, rigidity, hardness, and ability to take a smooth finish.

Back-silvered mirrors

The most common mirrors consist of a plate of transparent glass, with a thin reflective layer on the back (the side opposite to the incident and reflected light) backed by a coating that protects that layer against abrasion, tarnishing, and corrosion. The glass is usually soda-lime glass, but lead glass may be used for decorative effects, and other transparent materials may be used for specific applications.

A plate of transparent plastic may be used instead of glass, for lighter weight or impact resistance. Alternatively, a flexible transparent plastic film may be bonded to the front and/or back surface of the mirror, to prevent injuries in case the mirror is broken. Lettering or decorative designs may be printed on the front face of the glass, or formed on the reflective layer. The front surface may have an anti-reflection coating.

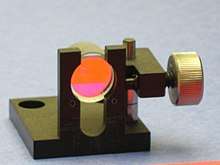

Front-silvered mirrors

Mirrors which are reflective on the front surface (the same side of the incident and reflected light) may be made of any rigid material.[31] The supporting material does not need to be transparent, but telescope mirrors often use glass anyway. Often a protective transparent coating is added on top of the reflecting layer, to protect it against abrasion, tarnishing, and corrosion, or to absorb certain wavelengths.

Flexible mirrors

Thin flexible plastic mirrors are sometimes used for safety, since they cannot shatter or produce sharp flakes. Their flatness is achieved by stretching them on a rigid frame. These usually consist of a layer of evaporated aluminum between two thin layers of transparent plastic.

By reflective material

In common mirrors, the reflective layer is usually some metal like silver, tin, nickel, or chromium, deposited by a wet process; or aluminum,[24][32] deposited by sputtering or evaporation in vacuum. The reflective layer may also be made of one or more layers of transparent materials with suitable indices of refraction.

The structural material may be a metal, in which case the reflecting layer may be just the surface of the same. Metal concave dishes are often used to reflect infrared light (such as in space heaters) or microwaves (as in satellite TV antennas). Some telescopes, such as the Sky Mirror and liquid metal telescopes, as well as mirrors for high-power laser cutting, also use all-metal mirrors.

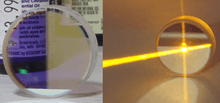

Mirrors that reflect only part of the light, while transmitting some of the rest, can be made with very thin metal layers or suitable combinations of dielectric layers. They are typically used as beamsplitters. A dichroic mirror, in particular, has surface that reflects certain wavelengths of light, while letting other wavelengths pass through. A cold mirror is a dichroic mirror that efficiently reflects the entire visible light spectrum while transmitting infrared wavelengths. A hot mirror is the opposite: it reflects infrared light while transmitting visible light. Dichroic mirrors are often used as filters to remove undesired components of the light in cameras and measuring instruments.

An active mirror will produce reflected beams that have more power than the incident beams. They are used to make disk lasers. The amplification is typically over a narrow range of wavelengths, and requires an external source of power.[33]

In X-ray telescopes, the X-rays incide on a highly precise metal surface at almost grazing angles, and only a small fraction of the rays are reflected.[34] In flying relativistic mirrors conceived for X-ray lasers, the reflecting surface is a spherical shockwave (wake wave) created in a low-density plasma by a very intense laser-pulse, and moving at an extremely high velocity.[35]

A phase-conjugating mirror uses nonlinear optics to reverse the phase difference between incident beams. Such mirrors may be used, for example, for combination and self-guiding of laser beams and correction of atmospheric distortions in imaging systems.[36][37][38]

Physical principles

When a sufficiently narrow beam of light is reflected at a point of a surface, the surface's normal direction will be the bisector of the angle formed by the two beams at that point. That is, the direction vector towards the incident beams's source, the normal vector , and direction vector of the reflected beam will be coplanar, and the angle between and will be equal to the angle of incidence between and , but of opposite sign.[39]

This property can be explained by the physics of an electromagnetic plane wave that is incident to a flat surface that is electrically conductive or where the speed of light changes abruptly, as between two materials with different indices of refraction.

- When parallel beams of light are reflected on a plane surface, the reflected rays will be parallel too.

- If the reflecting surface is concave, the reflected beams will be convergent, at least to some extent and for some distance from the surface.

- A convex mirror, on the other hand, will reflect parallel rays towards divergent directions.

More specifically, a concave parabolic mirror (whose surface is a part of a paraboloid of revolution) will reflect rays that are parallel to its axis into rays that pass through its focus. Conversely, a parabolic concave mirror will reflect any ray that comes from its focus towards a direction parallel to its axis. If a concave mirror surface is a part of a prolate ellipsoid, it will reflect any ray coming from one focus toward the other focus.[39]

A convex parabolic mirror, on the other hand, will reflect rays that are parallel to its axis into rays that seem to emanate from the focus of the surface, behind the mirror. Conversely, it will reflect incoming rays that converge toward that point into rays that are parallel to the axis. A convex mirror that is part of a prolate ellipsoid will reflect rays that converge towards one focus into divergent rays that seem to emanate from the other focus.[39]

Spherical mirrors do not reflect parallel rays to rays that converge to or diverge from a single point, or vice-versa, due to spherical aberration. However, a spherical mirror whose diameter is sufficiently small compared to the sphere's radius will behave very similarly to a parabolic mirror whose axis goes through the mirror's center and the center of that sphere; so that spherical mirrors can substitute for parabolic ones in many applications.[39]

A similar aberration occurs with parabolic mirrors when the incident rays are parallel among themselves but not parallel to the mirror's axis, or are divergent from a point that is not the focus — as when trying to form an image of an objet that is near the mirror or spans a wide angle as seen from it. However, this aberration can be sufficiently small if the object image is sufficiently far from the mirror and spans a sufficiently small angle around its axis.[39]

Mirror images

Objects viewed in a (plane) mirror will appear laterally inverted (e.g., if one raises one's right hand, the image's left hand will appear to go up in the mirror), but not vertically inverted (in the image a person's head still appears above their body).[40] However, a mirror does not usually "swap" left and right any more than it swaps top and bottom. A mirror typically reverses the forward/backward axis. To be precise, it reverses the object in the direction perpendicular to the mirror surface (the normal). Because left and right are defined relative to front-back and top-bottom, the "flipping" of front and back results in the perception of a left-right reversal in the image. (If you stand side-on to a mirror, the mirror really does reverse your left and right, because that's the direction perpendicular to the mirror.)

Looking at an image of oneself with the front-back axis flipped results in the perception of an image with its left-right axis flipped. When reflected in the mirror, your right hand remains directly opposite your real right hand, but it is perceived as the left hand of your image. When a person looks into a mirror, the image is actually front-back reversed, which is an effect similar to the hollow-mask illusion. Notice that a mirror image is fundamentally different from the object and cannot be reproduced by simply rotating the object.

For things that may be considered as two-dimensional objects (like text), front-back reversal cannot usually explain the observed reversal. In the same way that text on a piece of paper appears reversed if held up to a light and viewed from behind, text held facing a mirror will appear reversed, because the observer is behind the text. Another way to understand the reversals observed in images of objects that are effectively two-dimensional is that the inversion of left and right in a mirror is due to the way human beings turn their bodies. To turn from viewing the side of the object facing the mirror to view the reflection in the mirror requires the observer to look in the opposite direction. To look in another direction, human beings turn their heads about a vertical axis. This causes a left-right reversal in the image but not an up-down reversal.

Optical properties

Reflectivity

The reflectivity of a mirror is determined by the percentage of reflected light per the total of the incident light. The reflectivity may vary with wavelength. All or a portion of the light not reflected is absorbed by the mirror, while in some cases a portion may also transmit through. Although some small portion of the light will be absorbed by the coating, the reflectivity is usually higher for first-surface mirrors, eliminating both reflection and absorption losses from the substrate. The reflectivity is often determined by the type and thickness of the coating. When the thickness of the coating is sufficient to prevent transmission, all of the losses occur due to absorption. Aluminum is harder, less expensive, and more resistant to tarnishing than silver, and will reflect 85 to 90% of the light in the visible to near-ultraviolet range, but experiences a drop in its reflectance between 800 and 900 nm. Gold is very soft and easily scratched, costly, yet does not tarnish. Gold is greater than 96% reflective to near and far-infrared light between 800 and 12000 nm, but poorly reflects visible light with wavelengths shorter than 600 nm (yellow). Silver is expensive, soft, and quickly tarnishes, but has the highest reflectivity in the visual to near-infrared of any metal. Silver can reflect up to 98 or 99% of light to wavelengths as long as 2000 nm, but loses nearly all reflectivity at wavelengths shorter than 350 nm. Dielectric mirrors can reflect greater than 99.99% of light, but only for a narrow range of wavelengths, ranging from a bandwidth of only 10 nm to as wide as 100 nm for tunable lasers. However, dielectric coatings can also enhance the reflectivity of metallic coatings and protect them from scratching or tarnishing. Dielectric materials are typically very hard and relatively cheap, however the number of coats needed generally makes it an expensive process. In mirrors with low tolerances, the coating thickness may be reduced to save cost, and simply covered with paint to absorb transmission.[41]

Surface quality

Surface quality, or surface accuracy, measures the deviations from a perfect, ideal surface shape. Increasing the surface quality reduces distortion, artifacts, and aberration in images, and helps increase coherence, collimation, and reduce unwanted divergence in beams. For plane mirrors, this is often described in terms of flatness, while other surface shapes are compared to an ideal shape. The surface quality is typically measured with items like interferometers or optical flats, and are usually measured in wavelengths of light (λ). These deviations can be much larger or much smaller than the surface roughness. A normal household-mirror made with float glass may have flatness tolerances as low as 9–14λ per inch (25.4 mm), equating to a deviation of 5600 through 8800 nanometers from perfect flatness. Precision ground and polished mirrors intended for lasers or telescopes may have tolerances as high as λ/50 (1/50 of the wavelength of the light, or around 12 nm) across the entire surface.[42][41] The surface quality can be affected by factors such as temperature changes, internal stress in the substrate, or even bending effects that occur when combining materials with different coefficients of thermal expansion, similar to a bimetallic strip.[43]

Surface roughness

Surface roughness describes the texture of the surface, often in terms of the depth of the microscopic scratches left by the polishing operations. Surface roughness determines how much of the reflection is specular and how much diffuses, controlling how sharp or blurry the image will be.

For perfectly specular reflection, the surface roughness must be kept smaller than the wavelength of the light. Microwaves, which sometimes have a wavelength greater than an inch (~25 mm) can reflect specularly off a metal screen-door, continental ice-sheets, or desert sand, while visible light, having wavelengths of only a few hundred nanometers (a few hundred-thousandths of an inch), must meet a very smooth surface to produce specular reflection. For wavelengths that are approaching or are even shorter than the diameter of the atoms, such as X-rays, specular reflection can only be produced by surfaces that are at a grazing incidence from the rays.

Surface roughness is typically measured in microns, wavelength, or grit size, with ~80,000–100,000 grit or ~½λ–¼λ being "optical quality".[44][41][45]

Transmissivity

Transmissivity is determined by the percentage of light transmitted per the incident light. Transmissivity is usually the same from both first and second surfaces. The combined transmitted and reflected light, subtracted from the incident light, measures the amount absorbed by both the coating and substrate. For transmissive mirrors, such as one-way mirrors, beam splitters, or laser output couplers, the transmissivity of the mirror is an important consideration. The transmissivity of metallic coatings are often determined by their thickness. For precision beam-splitters or output couplers, the thickness of the coating must be kept at very high tolerances to transmit the proper amount of light. For dielectric mirrors, the thickness of the coat must always be kept to high tolerances, but it is often more the number of individual coats that determine the transmissivity. For the substrate, the material used must also have good transmissivity to the chosen wavelengths. Glass is a suitable substrate for most visible-light applications, but other substrates such as zinc selenide or synthetic sapphire may be used for infrared or ultraviolet wavelengths.[46]:p.104–108

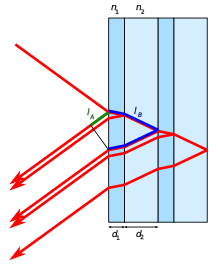

Wedge

Wedge errors are caused by the deviation of the surfaces from perfect parallelism. An optical wedge is the angle formed between two plane-surfaces (or between the principle planes of curved surfaces) due to manufacturing errors or limitations, causing one edge of the mirror to be slightly thicker than the other. Nearly all mirrors and optics with parallel faces have some slight degree of wedge, which is usually measured in seconds or minutes of arc. For first-surface mirrors, wedges can introduce alignment deviations in mounting hardware. For second-surface or transmissive mirrors, wedges can have a prismatic effect on the light, deviating its trajectory or, to a very slight degree, its color, causing chromatic and other forms of aberration. In some instances, a slight wedge is desirable, such as in certain laser systems where stray reflections from the uncoated surface are better dispersed than reflected back through the medium.[41][47]

Surface defects

Surface defects are small-scale, discontinuous imperfections in the surface smoothness. Surface defects are larger (in some cases much larger) than the surface roughness, but only affect small, localized portions of the entire surface. These are typically found as scratches, digs, pits (often from bubbles in the glass), sleeks (scratches from prior, larger grit polishing operations that were not fully removed by subsequent polishing grits), edge chips, or blemishes in the coating. These defects are often an unavoidable side-effect of manufacturing limitations, both in cost and machine precision. If kept low enough, in most applications these defects will rarely have any adverse effect, unless the surface is located at an image plane where they will show up directly. For applications that require extremely low scattering of light, extremely high reflectance, or low absorption due to high energy-levels that could destroy the mirror, such as lasers or Fabry-Perot interferometers, the surface defects must be kept to a minimum.[48]

Manufacturing

Mirrors are usually manufactured by either polishing a naturally reflective material, such as speculum metal, or by applying a reflective coating to a suitable polished substrate.[49]

In some applications, generally those that are cost-sensitive or that require great durability, such as for mounting in a prison cell, mirrors may be made from a single, bulk material such as polished metal. However, metals consist of small crystals (grains) separated by grain boundaries that may prevent the surface from attaining optical smoothness and uniform reflectivity.[13]:p.2,8

Coating

Silvering

The coating of glass with a reflective layer of a metal is generally called "silvering", even though the metal may not be silver. Currently the main processes are electroplating, "wet" chemical deposition, and vacuum deposition [13] Front-coated metal mirrors achieve reflectivities of 90–95% when new.

Dielectric coating

Applications requiring higher reflectivity or greater durability, where wide bandwidth is not essential, use dielectric coatings, which can achieve reflectivities as high as 99.997% over a limited range of wavelengths. Because they are often chemically stable and do not conduct electricity, dielectric coatings are almost always applied by methods of vacuum deposition, and most commonly by evaporation deposition. Because the coatings are usually transparent, absorption losses are negligible. Unlike with metals, the reflectivity of the individual dielectric-coatings is a function of Snell's law known as the Fresnel equations, determined by the difference in refractive index between layers. Therefore, the thickness and index of the coatings can be adjusted to be centered on any wavelength. Vacuum deposition can be achieved in a number of ways, including sputtering, evaporation deposition, arc deposition, reactive-gas deposition, and ion plating, among many others.[13]:p.103,107

Shaping and polishing

Tolerances

Mirrors can be manufactured to a wide range of engineering tolerances, including reflectivity, surface quality, surface roughness, or transmissivity, depending on the desired application. These tolerances can range from wide, such as found in a normal household-mirror, to extremely narrow, like those used in lasers or telescopes. Tightening the tolerances allows better and more precise imaging or beam transmission over longer distances. In imaging systems this can help reduce anomalies (artifacts), distortion or blur, but at a much higher cost. Where viewing distances are relatively close or high precision is not a concern, wider tolerances can be used to make effective mirrors at affordable costs.

Applications

Personal grooming

Mirrors are commonly used as aids to personal grooming.[50] They may range from small sizes, good to carry with oneself, to full body sized; they may be handheld, mobile, fixed or adjustable. A classic example of the latter is the cheval glass, which may be tilted.

Safety and easier viewing

- Convex mirrors

- Convex mirrors provide a wider field of view than flat mirrors,[51] and are often used on vehicles,[52] especially large trucks, to minimize blind spots. They are sometimes placed at road junctions, and corners of sites such as parking lots to allow people to see around corners to avoid crashing into other vehicles or shopping carts. They are also sometimes used as part of security systems, so that a single video camera can show more than one angle at a time. Convex mirrors as decoration are used in interior design to provide a predominantly experiential effect.[53]

- Mouth mirrors or "dental mirrors"

- Mouth mirrors or "dental mirrors" are used by dentists to allow indirect vision and lighting within the mouth. Their reflective surfaces may be either flat or curved.[54] Mouth mirrors are also commonly used by mechanics to allow vision in tight spaces and around corners in equipment.

- Rear-view mirrors

- Rear-view mirrors are widely used in and on vehicles (such as automobiles, or bicycles), to allow drivers to see other vehicles coming up behind them.[55] On rear-view sunglasses, the left end of the left glass and the right end of the right glass work as mirrors.

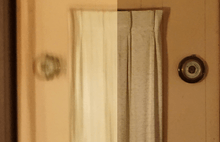

One-way mirrors and windows

- One-way mirrors

- One-way mirrors (also called two-way mirrors) work by overwhelming dim transmitted light with bright reflected light.[56] A true one-way mirror that actually allows light to be transmitted in one direction only without requiring external energy is not possible as it violates the second law of thermodynamics.:

- One-way windows

- One-way windows can be made to work with polarized light in the laboratory without violating the second law. This is an apparent paradox that stumped some great physicists, although it does not allow a practical one-way mirror for use in the real world.[57][58] Optical isolators are one-way devices that are commonly used with lasers.

Signalling

With the sun as light source, a mirror can be used to signal by variations in the orientation of the mirror. The signal can be used over long distances, possibly up to 60 kilometres (37 mi) on a clear day. This technique was used by Native American tribes and numerous militaries to transmit information between distant outposts.

Mirrors can also be used for search to attract the attention of search and rescue parties. Specialized type of mirrors are available and are often included in military survival kits.

Technology

Televisions and projectors

Microscopic mirrors are a core element of many of the largest high-definition televisions and video projectors. A common technology of this type is Texas Instruments' DLP. A DLP chip is a postage stamp-sized microchip whose surface is an array of millions of microscopic mirrors. The picture is created as the individual mirrors move to either reflect light toward the projection surface (pixel on), or toward a light absorbing surface (pixel off).

Other projection technologies involving mirrors include LCoS. Like a DLP chip, LCoS is a microchip of similar size, but rather than millions of individual mirrors, there is a single mirror that is actively shielded by a liquid crystal matrix with up to millions of pixels. The picture, formed as light, is either reflected toward the projection surface (pixel on), or absorbed by the activated LCD pixels (pixel off). LCoS-based televisions and projectors often use 3 chips, one for each primary color.

Large mirrors are used in rear projection televisions. Light (for example from a DLP as mentioned above) is "folded" by one or more mirrors so that the television set is compact.

Solar power

Mirrors are integral parts of a solar power plant. The one shown in the adjacent picture uses concentrated solar power from an array of parabolic troughs.[59]

Instruments

Telescopes and other precision instruments use front silvered or first surface mirrors, where the reflecting surface is placed on the front (or first) surface of the glass (this eliminates reflection from glass surface ordinary back mirrors have). Some of them use silver, but most are aluminium, which is more reflective at short wavelengths than silver. All of these coatings are easily damaged and require special handling. They reflect 90% to 95% of the incident light when new. The coatings are typically applied by vacuum deposition. A protective overcoat is usually applied before the mirror is removed from the vacuum, because the coating otherwise begins to corrode as soon as it is exposed to oxygen and humidity in the air. Front silvered mirrors have to be resurfaced occasionally to keep their quality. There are optical mirrors such as mangin mirrors that are second surface mirrors (reflective coating on the rear surface) as part of their optical designs, usually to correct optical aberrations.[60]

The reflectivity of the mirror coating can be measured using a reflectometer and for a particular metal it will be different for different wavelengths of light. This is exploited in some optical work to make cold mirrors and hot mirrors. A cold mirror is made by using a transparent substrate and choosing a coating material that is more reflective to visible light and more transmissive to infrared light.

A hot mirror is the opposite, the coating preferentially reflects infrared. Mirror surfaces are sometimes given thin film overcoatings both to retard degradation of the surface and to increase their reflectivity in parts of the spectrum where they will be used. For instance, aluminum mirrors are commonly coated with silicon dioxide or magnesium fluoride. The reflectivity as a function of wavelength depends on both the thickness of the coating and on how it is applied.

For scientific optical work, dielectric mirrors are often used. These are glass (or sometimes other material) substrates on which one or more layers of dielectric material are deposited, to form an optical coating. By careful choice of the type and thickness of the dielectric layers, the range of wavelengths and amount of light reflected from the mirror can be specified. The best mirrors of this type can reflect >99.999% of the light (in a narrow range of wavelengths) which is incident on the mirror. Such mirrors are often used in lasers.

In astronomy, adaptive optics is a technique to measure variable image distortions and adapt a deformable mirror accordingly on a timescale of milliseconds, to compensate for the distortions.

Although most mirrors are designed to reflect visible light, surfaces reflecting other forms of electromagnetic radiation are also called "mirrors". The mirrors for other ranges of electromagnetic waves are used in optics and astronomy. Mirrors for radio waves (sometimes known as reflectors) are important elements of radio telescopes.

Face-to-face mirrors

Two or more mirrors aligned exactly parallel and facing each other can give an infinite regress of reflections, called an infinity mirror effect. Some devices use this to generate multiple reflections:

- Fabry–Pérot interferometer

- Laser (which contains an optical cavity)

- 3D Kaleidoscope to concentrate light[62]

- momentum-enhanced solar sail[63]

Military applications

It has been said that Archimedes used a large array of mirrors to burn Roman ships during an attack on Syracuse. This has never been proven or disproved. On the TV show MythBusters, a team from MIT tried to recreate the famous "Archimedes Death Ray". They were unsuccessful at starting a fire on the ship.[64] Previous attempts to light the boat on fire using only the bronze mirrors available in Archimedes' time were unsuccessful, and the time taken to ignite the craft would have made its use impractical, resulting in the MythBusters team deeming the myth "busted". It was however found that the mirrors made it very difficult for the passengers of the targeted boat to see, likely helping to cause their defeat, which may have been the origin of the myth. (See solar power tower for a practical use of this technique.)

Seasonal lighting

Due to its location in a steep-sided valley, the Italian town of Viganella gets no direct sunlight for seven weeks each winter. In 2006 a €100,000 computer-controlled mirror, 8×5 m, was installed to reflect sunlight into the town's piazza. In early 2007 the similarly situated village of Bondo, Switzerland, was considering applying this solution as well.[65][66] In 2013, mirrors were installed to reflect sunlight into the town square in the Norwegian town of Rjukan.[67] Mirrors can be used to produce enhanced lighting effects in greenhouses or conservatories.

Architecture

Mirrors are a popular design theme in architecture, particularly with late modern and post-modernist high-rise buildings in major cities. Early examples include the Campbell Center in Dallas, which opened in 1972,[68] and the John Hancock Tower in Boston.

More recently, two skyscrapers designed by architect Rafael Viñoly, the Vdara in Las Vegas and 20 Fenchurch Street in London, have experienced unusual problems due to their concave curved glass exteriors acting as respectively cylindrical and spherical reflectors for sunlight. In 2010, the Las Vegas Review Journal reported that sunlight reflected off the Vdara's south-facing tower could singe swimmers in the hotel pool, as well as melting plastic cups and shopping bags; employees of the hotel referred to the phenomenon as the "Vdara death ray",[69] aka the "fryscraper." In 2013, sunlight reflecting off 20 Fenchurch Street melted parts of a Jaguar car parked nearby and scorching or igniting the carpet of a nearby barber shop.[70] This building had been nicknamed the "walkie-talkie" because its shape was supposedly similar to a certain model of two-way radio; but after its tendency to overheat surrounding objects became known, the nickname changed to the "walkie-scorchie."

Fine art

Paintings

Painters depicting someone gazing into a mirror often also show the person's reflection. This is a kind of abstraction—in most cases the angle of view is such that the person's reflection should not be visible. Similarly, in movies and still photography an actor or actress is often shown ostensibly looking at him- or herself in the mirror, and yet the reflection faces the camera. In reality, the actor or actress sees only the camera and its operator in this case, not their own reflection. In the psychology of perception, this is known as the Venus effect.

The mirror is the central device in some of the greatest of European paintings:

- Édouard Manet's A Bar at the Folies-Bergère

- Titian's Venus with a Mirror

- Jan van Eyck's Arnolfini Portrait

- Pablo Picasso's Girl before a Mirror (1932)

- Diego Velázquez's Rokeby Venus

- Diego Velázquez's Las Meninas, wherein the viewer is both the watcher (of a self-portrait in progress) and the watched, and the many adaptations of that painting in various media

- Veronese's Venus with a Mirror

Mirrors have been used by artists to create works and hone their craft:

- Filippo Brunelleschi discovered linear perspective with the help of the mirror.[71]

- Leonardo da Vinci called the mirror the "master of painters". He recommended, "When you wish to see whether your whole picture accords with what you have portrayed from nature take a mirror and reflect the actual object in it. Compare what is reflected with your painting and carefully consider whether both likenesses of the subject correspond, particularly in regard to the mirror."[72]

- Many self-portraits are made possible through the use of mirrors, such as the great self-portraits by Dürer, Frida Kahlo, Rembrandt, and Van Gogh. M. C. Escher used special shapes of mirrors in order to achieve a much more complete view of his surroundings than by direct observation in Hand with Reflecting Sphere (also known as Self-Portrait in Spherical Mirror).

Mirrors are sometimes necessary to fully appreciate art work:

- István Orosz's anamorphic works are images distorted such that they only become clearly visible when reflected in a suitably shaped and positioned mirror.[73]

Sculpture

_Sala_d'aspetto_per_la_casa_di_M.me_B.%2C1939.jpg)

- Anamorphosis projecting sculpture into mirrors

Contemporary anamorphic artist Jonty Hurwitz uses cylindrical mirrors to project distorted sculptures.[74]

- Sculptures comprised entirely or in part of mirrors

- Infinity Also Hurts is a mirror, glass and silicone sculpture by artist, Seth Wulsin

- Sky Mirror is a public sculpture by artist, Anish Kapoor

Other artistic mediums

.jpg)

Some other contemporary artists use mirrors as the material of art:

- A Chinese magic mirror is an art in which the face of the bronze mirror projects the same image that was cast on its back. This is due to minute curvatures on its front.[75]

- Specular holography uses a large number of curved mirrors embedded in a surface to produce three-dimensional imagery.

- Paintings on mirror surfaces (such as silkscreen printed glass mirrors)

- Special mirror installations

- Follow Me mirror labyrinth by artist, Jeppe Hein (see also, Entertainment: Mirror mazes, below)

- Mirror Neon Cube by artist, Jeppe Hein

Religious Function of the real and depicted mirror

In the Middle Ages mirrors existed in various shapes for multiple uses. Mostly they were used as an accessory for personal hygiene but also as tokens of courtly love, made from ivory in the ivory carving centers in Paris, Cologne and the Southern Netherlands.[76] They also had their uses in religious contexts as they were integrated in a special form of pilgrims badges or pewter/lead mirror boxes[77] since the late 14th century. Burgundian ducal inventories show us that the dukes owned a mass of mirrors or objects with mirrors, not only with religious iconography or inscriptions, but combined with reliquaries, religious paintings or other objects that were distinctively used for personal piety.[78] Considering mirrors in paintings and book illumination as depicted artifacts and trying to draw conclusions about their functions from their depicted setting, one of these functions is to be an aid in personal prayer to achieve self-knowledge and knowledge of God, in accord with contemporary theological sources. E.g. the famous Arnolfini-Wedding by Jan van Eyck shows a constellation of objects that can be recognized as one which would allow a praying man to use them for his personal piety: the mirror surrounded by scenes of the Passion to reflect on it and on oneself, a rosary as a device in this process, the veiled and cushioned bench to use as a prie-dieu, and the abandoned shoes that point in the direction in which the praying man kneeled.[78] The metaphorical meaning of depicted mirrors is complex and many-layered, e.g. as an attribute of Mary, the “speculum sine macula”, or as attributes of scholarly and theological wisdom and knowledge as they appear in book illuminations of different evangelists and authors of theological treatises. Depicted mirrors – orientated on the physical properties of a real mirror – can be seen as metaphors of knowledge and reflection and are thus able to remind the beholder to reflect and get to know himself. The mirror may function simultaneously as a symbol and a device of a moral appeal. That is also the case if it is shown in combination with virtues and vices, a combination which also occurs more frequently in the 15th century: The moralizing layers of mirror metaphors remind the beholder to examine himself thoroughly according to his own virtuous or vicious life. This is all the more true if the mirror is combined with iconography of death. Not only is Death as a corpse or skeleton holding the mirror for the still living personnel of paintings, illuminations and prints, but the skull appears on the convex surfaces of depicted mirrors, showing the painted and real beholder his future face.[78]

Decoration

.jpg)

Mirrors are frequently used in interior decoration and as ornaments:

- Mirrors, typically large and unframed, are frequently used in interior decoration to create an illusion of space and amplify the apparent size of a room.[79] They come also framed in a variety of forms, such as the pier glass and the overmantel mirror.

- Mirrors are used also in some schools of feng shui, an ancient Chinese practice of placement and arrangement of space to achieve harmony with the environment.

- The softness of old mirrors is sometimes replicated by contemporary artisans for use in interior design. These reproduction antiqued mirrors are works of art and can bring color and texture to an otherwise hard, cold reflective surface. It is an artistic process that has been attempted by many and perfected by few.

- A decorative reflecting sphere of thin metal-coated glass, working as a reducing wide-angle mirror, is sold as a Christmas ornament called a bauble.

- Some pubs and bars hang mirrors depicting the logo of a brand of liquor, beer or drinking establishment.

Entertainment

- Illuminated rotating disco balls covered with small mirrors are used to cast moving spots of light around a dance floor.

- The hall of mirrors, commonly found in amusement parks, is an attraction in which a number of distorting mirrors are used to produce unusual reflections of the visitor.

- Mirrors are employed in kaleidoscopes, personal entertainment devices invented in Scotland by Sir David Brewster.

- Mirrors are often used in magic to create an illusion. One effect is called Pepper's ghost.

- Mirror mazes, often found in amusement parks as well, contain large numbers of mirrors and sheets of glass. The idea is to navigate the disorientating array without bumping into the walls. Mirrors in attractions like this are often made of Plexiglas as to assure that they do not break.[80]

Film and television

- Candyman is a horror film about a malevolent spirit summoned by speaking its name in front of a mirror.

- Mirrors is a horror film about haunted mirrors that reflect different scenes than those in front of them.

- Poltergeist III features mirrors that do not reflect reality and which can be used as portals to the afterlife.

- Oculus is a horror film about a haunted mirror that causes people to hallucinate and commit acts of violence.

- The 10th Kingdom miniseries requires the characters to use a magic mirror to travel between New York City (the 10th Kingdom) and the Nine Kingdoms of fairy tale.

Literature

Mirrors play a powerful role in cultural literature.

- Christian Bible passages, 1 Corinthians 13:12 ("Through a Glass Darkly") and 2 Corinthians 3:18, reference a dim mirror image or poor mirror reflection.

- Narcissus of Greek mythology wastes away while gazing, self-admiringly, at his reflection in water.

- The Song dynasty history Zizhi Tongjian Comprehensive Mirror in Aid of Governance by Sima Guang is so titled because "mirror" (鑑, jiàn) is used metaphorically in Chinese to refer to gaining insight by reflecting on past experience or history.

- In the European fairy tale, Snow White (collected by the Brothers Grimm in 1812), the evil queen asks, "Mirror, mirror, on the wall... who's the fairest of them all?"

- In Alfred, Lord Tennyson's famous poem The Lady of Shalott (1833, revised in 1842), the titular character possesses a mirror that enables her to look out on the people of Camelot, as she is under a curse that prevents her from seeing Camelot directly.

- Hans Christian Andersen's fairy tale The Snow Queen, in which the devil, in a form of an evil troll,[81] has made a magic mirror that distorts the appearance of everything that it reflects.

- Lewis Carroll's Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There (1871) is one of the best-loved uses of mirrors in literature. The text itself utilizes a narrative that mirrors that of its predecessor, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland.[82]

- In Oscar Wilde's novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890), a portrait serves as a magical mirror that reflects the true visage of the perpetually youthful protagonist, as well as the effect on his soul of each sinful act.[83][84]

- The short story Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius by Jorge Luis Borges begins with the phrase "I owe the discovery of Uqbar to the conjunction of a mirror and an encyclopedia" and contains other references to mirrors.

- The Trap, a short story by H.P. Lovecraft and Henry S. Whitehead, centers around a mirror. "It was on a certain Thursday morning in December that the whole thing began with that unaccountable motion I thought I saw in my antique Copenhagen mirror. Something, it seemed to me, stirred—something reflected in the glass, though I was alone in my quarters."[85]

- The magical objects in the Harry Potter series (1997–2011) include the Mirror of Erised and two-way mirrors.

- Under Appendix: Variant Planes & Cosmologies of the Dungeons & Dragons Manual Of The Planes (2000), is The Plane of Mirrors (page 204).[86] It describes the Plane of Mirrors as a space existing behind reflective surfaces, and experienced by visitors as a long corridor. The greatest danger to visitors upon entering the plane is the instant creation of a mirror-self with the opposite alignment of the original visitor.

- The Mirror Thief, a novel by Martin Seay (2016),[87] includes a fictional account of industrial espionage surrounding mirror manufacturing in 16th century Venice.

- The Reaper's Image, a short story by Stephen King, concerns a rare Elizabethan mirror that displays the Reaper's image when viewed, which symbolises the death of the viewer.

- Kilgore Trout, a protagonist of Kurt Vonnegut's novel Breakfast of Champions, believes that mirrors are windows to other universes, and refers to them as "leaks," a recurring motif in the book.

Mirrors and animals

Only a few animal species have been shown to have the ability to recognize themselves in a mirror, most of them mammals. Experiments have found that the following animals can pass the mirror test:

- All great apes:

- Humans. Humans tend to fail the mirror test until they are about 18 months old, or what psychoanalysts call the "mirror stage".[88][89][90]

- Bonobos[91]

- Chimpanzees[91][92]

- Orangutans[93]

- Gorillas. Initially, it was thought that gorillas did not pass the test, but there are now several well-documented reports of gorillas (such as Koko[94]) passing the test.

- Bottlenose dolphins[95]

- Orcas[96]

- Elephants[97]

- European magpies[98]

- Jumping spiders, specifically of the genus Portia

See also

Bibliography

- Le miroir: révélations, science-fiction et fallacies. Essai sur une légende scientifique, Jurgis Baltrušaitis, Paris, 1978. ISBN 2020049856.

- On reflection, Jonathan Miller, National Gallery Publications Limited (1998). ISBN 0-300-07713-0.

- Lo specchio, la strega e il quadrante. Vetrai, orologiai e rappresentazioni del 'principium individuationis' dal Medioevo all'Età moderna, Francesco Tigani, Roma, 2012. ISBN 978-88-548-4876-4.

References

- Entry "looking glass" in the online Cambridge Dictionary. Accessed on 2020-05-04.

- Mark Pendergrast (2004): Mirror Mirror: A History of the Human Love Affair With Reflection. Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-05471-4

- M. A. Kallistratova (1997). "Physical grounds for acoustic remote sensing of the atmospheric boundary layer". Acoustic Remote Sensing Applications. Lecture Notes in Earth Sciences. 69. Springer. pp. 3–34. Bibcode:1997LNES...69....3K. doi:10.1007/BFb0009558. ISBN 978-3-540-61612-2.

- Fioratti, Helen. "The Origins of Mirrors and their uses in the Ancient World". L'Antiquaire & the Connoisseur. Archived from the original on 3 February 2011. Retrieved 14 August 2009.

- History of Mirrors Dating Back 8000 Years, Jay M. Enoch, School of Optometry, University of California at Berkeley

- The National Museum of Science and Technology, Stockholm Archived 3 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Whiton, Sherrill (16 April 2013). Elements Of Interior Design And Decoration. Read Books Ltd. ISBN 9781447498230.

- "A Brief History of Mirrors". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 28 April 2020. Retrieved 14 August 2009.

- "Speculum". Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- Joseph Needham (1974). Science and Civilisation in China. Cambridge University Press. p. 238. ISBN 978-0-521-08571-7.

- Albert Allis Hopkins (1910). The Scientific American cyclopedia of formulas: partly based upon the 28th ed. of Scientific American cyclopedia of receipts, notes and queries. Munn & co., inc. p. 89.

- Sabine Melchoir-Bonnet (2011): The Mirror: A History by – Routledge 2011. ISBN 978-0415924481

- H. Pulker, H.K. Pulker (1999): Coatings on Glass. Elsevier 1999

- Pliny the Elder (ca. 77 CE): 'Natural History.

- Holland, Patricia. "Mirrors". Isnare Free Articles. Retrieved 14 August 2009.

- The Book of the Mirror Archived 11 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, edited by Miranda Anderson

- Wondrous Glass: Images and Allegories Archived 13 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Kelsey Museum of Archaeology

- Mirrors in Egypt, Digital Egypt for Universities

- Archaeominerology By George Rapp – Springer Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2009 page 180

- Kasem Ajram (1992). The Miracle of Islam Science (2nd ed.). Knowledge House Publishers. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-911119-43-5.

- Hadsund, Per (1993). "The Tin-Mercury Mirror: Its Manufacturing Technique and Deterioration Processes". Studies in Conservation. 38 (1): 3–16. doi:10.1179/sic.1993.38.1.3. JSTOR 1506387.

- "Mirror Reflection – Interesting Materials to use in interior design (I) – Iri's Interior Design World". Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- Liebig, Justus (1856). "Ueber Versilberung und Vergoldung von Glas". Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie. 98 (1): 132–139. doi:10.1002/jlac.18560980112.

- "Mirror Manufacturing and Composition". Mirrorlink.org. Archived from the original on 14 February 2015. Retrieved 3 June 2014.

- The Foundations of Vacuum Coating Technology By D. M. Mattox -- Springer 2004 Page 37

- pp. 162–164, Apollonius of Perga's Conica: text, context, subtext, Michael N. Fried and Sabetai Unguru, Brill, 2001, ISBN 90-04-11977-9.

- Smith, A. Mark (1996). "Ptolemy's Theory of Visual Perception: An English Translation of the "Optics" with Introduction and Commentary". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. New Series. 86 (2): iii–300. doi:10.2307/3231951. JSTOR 3231951.

- Rashed, Roshdi (1990). "A Pioneer in Anaclastics: Ibn Sahl on Burning Mirrors and Lenses". Isis. 81 (3): 464–491 [465, 468, 469]. doi:10.1086/355456.

- R. S. Elliott (1966). Electromagnetics, Chapter 1. McGraw-Hill.

- Dr. Mahmoud Al Deek. "Ibn Al-Haitham: Master of Optics, Mathematics, Physics and Medicine", Al Shindagah, November–December 2004.

- Molded Optics: Design and Manufacture By Michael Schaub, Jim Schwiegerling, Eric Fest, R. Hamilton Shepard, Alan Symmons -- CRC Press 2011 Page 88–89

- Saunders, Nigel (6 February 2004). Aluminum and the Elements of Group 13. Capstone Classroom. ISBN 9781403454959.

- Wang, Wei-Chih. "PME4031: Engineering Optips" (PDF). University of Washington. National Tsinghua University. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- V.V. Protopopov; V.A. Shishkov, and V.A. Kalnov (2000). "X-ray parabolic collimator with depth-graded multilayer mirror". Review of Scientific Instruments. 71 (12): 4380–4386. Bibcode:2000RScI...71.4380P. doi:10.1063/1.1327305.

- X-Ray Lasers 2008: Proceedings of the 11th International Conference By Ciaran Lewis, Dave Riley == Springer 2009 Page 34

- Basov, N G; Zubarev, I G; Mironov, A B; Mikhailov, S I; Okulov, A Yu (1980). "Laser interferometer with wavefront reversing mirrors". Sov. Phys. JETP. 52 (5): 847. Bibcode:1980ZhETF..79.1678B.

- Okulov, A Yu (2014). "Coherent chirped pulse laser network with Mickelson phase conjugator". Applied Optics. 53 (11): 2302–2311. arXiv:1311.6703. doi:10.1364/AO.53.002302. PMID 24787398.

- Bowers, M W; Boyd, R W; Hankla, A K (1997). "Brillouin-enhanced four-wave-mixing vector phase-conjugate mirror with beam-combining capability". Optics Letters. 22 (6): 360–362. doi:10.1364/OL.22.000360. PMID 18183201.

- Katz, Debora M. (1 January 2016). Physics for Scientists and Engineers: Foundations and Connections. Cengage Learning. ISBN 9781337026369.

- Arago, François; Lardner, Dionysius (1845). Popular Lectures on Astronomy: Delivered at the Royal Observatory of Paris. Greeley & McElrath.

- Bruce H. Walker (1998): Optical Engineering Fundamentals. Spie Optical Engineering Press

- The Principles of Astronomical Telescope Design By Jingquan Cheng -- Springer 2009 Page 87

- Mems/Nems: Volume 1 Handbook Techniques and Applications Design Methods By Cornelius T. Leondes -- Springer 2006 Page 203

- Düzgün, H. Şebnem; Demirel, Nuray (2011). Remote Sensing of the Mine Environment. CRC Press. p. 24.

- Warner, Timothy A.; Nellis, M. Duane; Foody, Giles M. The SAGE Handbook of Remote Sensing. SAGE. pp. 349–350.

- Synchrotron Radiation Sources and Applications By G.N Greaves, I.H Munro -- Sussp Publishing 1989

- Mirrors and windows for high power/high energy laser systems by Claude A Klein -- SPIE Optical Engineering Press 1989 Page 158

- https://wp.optics.arizona.edu/optomech/wp-content/uploads/sites/53/2016/08/10-Specifying-optical-components.pdf

- Lanzagorta, Marco (2012). Quantum Radar. Morgan & Claypool Publishers. ISBN 9781608458264.

- Schram, Joseph F. (1 January 1969). Planning & remodeling bathrooms. Lane Books. ISBN 9780376013224.

- Taylor, Charles (2000). The Kingfisher Science Encyclopedia. Kingfisher. p. 266. ISBN 9780753452691.

- Assessment of Vehicle Safety Problems for Special Driving Populations: Final Report. U.S. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. 1979.

- "The Charm of Convex Mirrors". 6 February 2016.

- Anderson, Pauline Carter; Pendleton, Alice E. (2000). The Dental Assistant. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0766811133.

- Board, Editorial. The Gist of NCERT -- GENERAL SCIENCE. Kalinjar Publications. ISBN 9789351720188.

- "How Do Two-Way Mirrors Work?". 2 November 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- Mungan, C.E. (1999). "Faraday Isolators and Kirchhoff's Law: A Puzzle" (PDF). Retrieved 18 July 2006.

- Rayleigh (10 October 1901). "On the magnetic rotation of light and the second law of thermodynamics". Nature. 64 (1667): 577. doi:10.1038/064577e0.

- Palenzuela, Patricia; Alarcón-Padilla, Diego-César; Zaragoza, Guillermo (9 October 2015). Concentrating Solar Power and Desalination Plants: Engineering and Economics of Coupling Multi-Effect Distillation and Solar Plants. Springer. ISBN 9783319205359.

- "Mirror Lenses – how good? Tamron 500/8 SP vs Canon 500/4.5L". Bobatkins.com. Retrieved 3 June 2014.

- "Super-thin Mirror Under Test at ESO". ESO Picture of the Week. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

- Ivan Moreno (2010). "Output irradiance of tapered lightpipes" (PDF). JOSA A. 27 (9): 1985–93. Bibcode:2010JOSAA..27.1985M. doi:10.1364/JOSAA.27.001985. PMID 20808406. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 March 2012. Retrieved 3 September 2011.

- Meyer, Thomas R.; Mckay, Christopher P.; Mckenna, Paul M. (1 October 1987), The laser elevator – Momentum transfer using an optical resonator, NASA, IAF PAPER 87–299

- "2.009 Archimedes Death Ray: Testing with MythBusters". Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- "Italy village gets 'sun mirror'". BBC News. 18 December 2006. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- "Swiss Officials Want to Spread Sunshine, Swiss Officials May Build Giant Mirror to Give Light to Sunless Village – CBS News". Archived from the original on 17 March 2009.

- Mirrors finally bring winter sun to Rjukan in Norway, BBC News, 30 October 2013

- Steve Brown (17 May 2012). "Reflections on mirrored glass: '70s bling buildings still shine". Dallas Morning News.

- "Vdara visitor: 'Death ray' scorched hair". 25 September 2010.

- "'Death Ray II'? London Building Reportedly Roasts Cars".

- Camp, Pannill (4 December 2014). The First Frame. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107079168.

- Leonardo da Vinci, The Notebooks of Leonardo Da Vinci, XXIX : Precepts of the Painter, Tr. Edward MacCurdy (1938)

- Kurze, Caroline (30 January 2015). "Anamorphic Art by István Orosz". Ignant. Archived from the original on 3 December 2017.

- "The skewed anamorphic sculptures and engineered illusions of Jonty Hurwitz". Christopher Jobson, Colossal. 21 January 2013.

- "Magic Mirrors" (PDF). The Courier: 16–17. October 1988. ISSN 0041-5278. Retrieved 23 August 2011.

- "Gothic Ivories Project at The Courtauld Institute of Art, London". www.gothicivories.courtauld.ac.uk. 1 October 2008. Archived from the original on 28 July 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2018. Search for "mirror case" or "mirror".

- "Lid of a mirror box". Museum Bojmans van Beuningen, Rotterdam. Retrieved 29 July 2018. See this example of a pewter mirror box from around 1450–1500.

- Scheel, Johanna (2013). Das altniederländische Stifterbild. Emotionsstrategien des Sehens und der Selbsterkenntnis. Berlin: Gebr. Mann. pp. 342–351. ISBN 978-3-7861-2695-9.

- "Product Design: Futuristic, Liquid Mirror Door". Archived from the original on 14 October 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- Dale Samuelson, Wendy Yegoiants (2001). The American Amusement Park. MBI Publishing Company. pp. 65.

- Andersen, Hans Christian (1983). "The Snow Queen". The Complete Fairy Tales and Stories. trans. Erik Christian Haugaard. United States: Anchor Books. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- Carroll, Lewis (1872). "Through the Looking-glass: And what Alice Found There". Macmillan Children's. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- Simon Callow (19 September 2009). "Mirror, mirror". The Guardian. The Guardian: Culture Web. Retrieved 20 November 2010.

- "The Picture of Dorian Gray". Sparknotes.com. Retrieved 20 November 2010.

- ""The Trap" by H. P. Lovecraft". hplovecraft.com.

- Grubb, Jeff; David Noonan; Bruce R. Cordell (2001). Manual Of The Planes. Wizards of the Coast. ISBN 978-0-7869-1850-8.

- Seay, Martin (2016). The Mirror Thief. Melville House. ISBN 9781612195148.

- "Consciousness and the Symbolic Universe". Ulm.edu. Retrieved 3 June 2014.

- Stanley Coren (2004). How dogs think. ISBN 978-0-7432-2232-7.

- Archer, John (1992). Ethology and Human Development. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-389-20996-6.

- Miller, Jason (2009). "Minding the Animals: Ethology and the Obsolescence of Left Humanism". American Chronicle. Retrieved 21 May 2009.

- Daniel, Povinellide Veer, Monique; Gallup Jr., Gordon; Theall, Laura; van den Bos, Ruud (2003). "An 8-year longitudinal study of mirror self-recognition in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes)". Neuropsychologia. 41 (2): 229–334. doi:10.1016/S0028-3932(02)00153-7. ISSN 0028-3932. PMID 12459221.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "National Geographic documentary "Human Ape"". Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- Francine Patterson and Wendy Gordon The Case for Personhood of Gorillas Archived 25 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine. In The Great Ape Project, ed. Paola Cavalieri and Peter Singer, St. Martin's Griffin, 1993, pp. 58–77.

- Marten, K. & Psarakos, S. (1995). "Evidence of self-awareness in the bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus)". In Parker, S.T.; Mitchell, R. & Boccia, M. (eds.). Self-awareness in Animals and Humans: Developmental Perspectives. Cambridge University Press. pp. 361–379. Archived from the original on 13 October 2008. Retrieved 4 October 2008.

- Delfour, F; Marten, K (2001). "Mirror image processing in three marine mammal species: killer whales (Orcinus orca), false killer whales (Pseudorca crassidens) and California sea lions (Zalophus californianus)". Behavioural Processes. 53 (3): 181–190. doi:10.1016/s0376-6357(01)00134-6. PMID 11334706.

- Joshua M. Plotnik, Frans B.M. de Waal, and Diana Reiss (2006) Self-recognition in an Asian elephant. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 103(45):17053–17057 10.1073/pnas.0608062103 abstract

- Prior, Helmut; Schwarz, Ariane; Güntürkün, Onur; De Waal, Frans (2008). De Waal, Frans (ed.). "Mirror-Induced Behavior in the Magpie (Pica pica): Evidence of Self-Recognition" (PDF). PLOS Biology. 6 (8): e202. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0060202. PMC 2517622. PMID 18715117. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 November 2008. Retrieved 21 August 2008.

External links

| Look up mirror in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Mirror |

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 18 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 575–577.

- Mirror Manufacturing and Composition, Mirrorlink

- Video of Mirror Making on YouTube

- How Mirrors Are Made (video), Glass Association of North America (GANA)

- July 2019 "The Ugly History of Beautiful Things: Mirrors" by Katy Kelleher for Longreads