Antler

Antlers are extensions of an animal's skull found in members of the deer family. Antlers are true bone and are a single structure. They are generally found only on males, with the exception of the reindeer/caribou.[1] Antlers are shed and regrown each year and function primarily as objects of sexual attraction and as weapons in fights between males for control of harems.

In contrast, horns, found on pronghorns and bovids such as sheep, goats, bison and cattle, are two-part structures. An interior of bone (also an extension of the skull) is covered by an exterior sheath made of keratin, the same material as human fingernails and toenails, grown by specialized hair follicles. Horns are never shed and continue to grow throughout the animal's life. The exception to this rule is the pronghorn which sheds and regrows its horn sheath each year. They usually grow in symmetrical pairs.

Etymology

Antler comes from the Old French antoillier (see present French : "Andouiller", from ant-, meaning before, oeil, meaning eye and -ier, a suffix indicating an action or state of being)[2][3] possibly from some form of an unattested Latin word *anteocularis, "before the eye"[4] (and applied to the word for "branch"[5] or "horn"[3]).

Evolution and function

Antlers are unique to cervids. The ancestors of deer had tusks (long upper canine teeth). In most species, antlers appear to replace tusks. However, one modern species (the water deer) has tusks and no antlers and the muntjac has small antlers and tusks. The musk deer, which are not true cervids, also bear tusks in place of antlers.[6]

Antlers are usually found only on males. Only reindeer (known as caribou in North America) have antlers on the females, and these are normally smaller than those of the males. Nevertheless, fertile does from other species of deer have the capacity to produce antlers on occasion, usually due to increased testosterone levels.[7] The "horns" of a pronghorn (which is not a cervid but a giraffoid) meet some of the criteria of antlers, but are not considered true antlers because they contain keratin.[8]

Development

Each antler grows from an attachment point on the skull called a pedicle. While an antler is growing, it is covered with highly vascular skin called velvet, which supplies oxygen and nutrients to the growing bone.[6] Antlers are considered one of the most exaggerated cases of male secondary sexual traits in the animal kingdom,[9] and grow faster than any other mammal bone.[10] Growth occurs at the tip, and is initially cartilage, which is later replaced by bone tissue. Once the antler has achieved its full size, the velvet is lost and the antler's bone dies. This dead bone structure is the mature antler. In most cases, the bone at the base is destroyed by osteoclasts and the antlers fall off at some point.[6] As a result of their fast growth rate, antlers are considered a handicap since there is an immense nutritional demand on deer to re-grow antlers annually, and thus can be honest signals of metabolic efficiency and food gathering capability.[11]

In most arctic and temperate-zone species, antler growth and shedding is annual, and is controlled by the length of daylight. Although the antlers are regrown each year, their size varies with the age of the animal in many species, increasing annually over several years before reaching maximum size. In tropical species, antlers may be shed at any time of year, and in some species such as the sambar, antlers are shed at different times in the year depending on multiple factors. Some equatorial deer never shed their antlers. Antlers function as weapons in combats between males, which sometimes cause serious wounds, and as dominance and sexual displays.[10]

Sexual selection

The principal means of evolution of antlers is sexual selection, which operates via two mechanisms: male-to-male competition (behaviorally, physiologically) and female mate choice.[9] Male-male competition can take place in two forms. First, they can compete behaviorally where males use their antlers as weapons to compete for access to mates; second, they can compete physiologically where males present their antlers to display their strength and fertility competitiveness to compete for access to mates.[9] Males with the largest antlers are more likely to obtain mates and achieve the highest fertilization success due to their competitiveness, dominance and high phenotypic quality.[9] Whether this is a result of male-male fighting or display, or of female choosiness differs depending on the species as the shape, size, and function of antlers vary between species.[12]

Heritability and reproductive advantage

There is evidence to support that antler size influences mate selection in the red deer, and has a heritable component. Despite this, a 30-year study showed no shift in the median size of antlers in a population of red deer.[13] The lack of response could be explained by environmental covariance, meaning that lifetime breeding success is determined by an unmeasured trait which is phenotypically correlated with antler size but for which there is no genetic correlation of antler growth.[13] Alternatively, the lack of response could be explained by the relationship between heterozygosity and antler size, which states that males heterozygous at multiple loci, including MHC loci, have larger antlers.[14] The evolutionary response of traits that depend on heterozygosity is slower than traits that are dependent on additive genetic components and thus the evolutionary change is slower than expected.[14] A third possibility is that the costs of having larger antlers (resource use, and mobility detriments, for instance) exert enough selective pressure to offset the benefit of attracting mates; thereby stabilizing antler size in the population.

Protection against predation

If antlers functioned only in male–male competition for mates, the best evolutionary strategy would be to shed them immediately after the rutting season, both to free the male from a heavy encumbrance and to give him more time to regrow a larger new pair. Yet antlers are commonly retained through the winter and into the spring,[15] suggesting that they have another use. Wolves in Yellowstone National Park are 3.6 times more likely to attack individual male elk without antlers, or groups of elk in which at least one male is without antlers.[15] Half of all male elk killed by wolves lack antlers, at times in which only one quarter of all males have shed antlers. These findings suggest that antlers have a secondary function in deterring predation.

Diversification

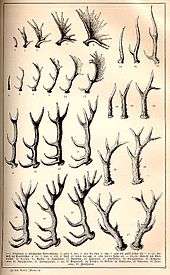

The diversification of antlers, body size and tusks has been strongly influenced by changes in habitat and behavior (fighting and mating).[12]

Capreolinae

Reindeer (genus Rangifer, whose sole member species R. tarandus comprises several distinctive subspecies of reindeer and caribou) use their antlers to clear away snow so they can eat the vegetation underneath. This is one possible reason that females of this species evolved antlers.[6] Another possible reason is for female competition during winter foraging.[12] Male and female reindeer antlers differ in several respects. Males shed their antlers prior to winter, while female antlers are retained throughout winter.[16] Also, female antler size plateaus at the onset of puberty, around age three, while males' antler size increases during their lifetime.[17] This likely reflects the differing life history strategies of the two sexes, where females are resource limited in their reproduction and cannot afford costly antlers, while male reproductive success depends on the size of their antlers because they are under directional sexual selection.[17]

In moose, antlers may act as large hearing aids. Equipped with large, highly adjustable external ears, moose have highly sensitive hearing. Moose with antlers have more sensitive hearing than moose without, and a study of trophy antlers with an artificial ear confirmed that the large flattened (palmate) antler behaves like a parabolic reflector.[19]

A mule deer with relatively large antlers

A mule deer with relatively large antlers

Cervinae

Irish elk are now extinct

Irish elk are now extinct Young red deer, with velvet

Young red deer, with velvet- American elk, or wapiti

- Sambar deer with thick, forked beams for antlers.

Exploitation by other species

Ecological role

Discarded antlers represent a source of calcium, phosphorus and other minerals and are often gnawed upon by small animals, including squirrels, porcupines, rabbits and mice. This is more common among animals inhabiting regions where the soil is deficient in these minerals. Antlers shed in oak forest inhabited by squirrels are rapidly chewed to pieces by them.[20][21]

Trophy hunting

Antlered heads are prized as trophies with larger sets being more highly prized. The first organization to keep records of sizes was Rowland Ward Ltd., a London taxidermy firm, in the early 20th century. For a time only total length or spread was recorded. In the middle of the century, the Boone and Crockett Club and the Safari Club International developed complex scoring systems based on various dimensions and the number of tines or points, and they keep extensive records of high-scoring antlers.[22] Deer bred for hunting on farms are selected based on the size of the antlers.[23]

Hunters have developed terms for antler parts: beam, palm, brow, bez or bay, trez or tray, royal, and surroyal. These are the main shaft, flattened center, first tine, second tine, third tine, fourth tine, and fifth or higher tines, respectively.[24] The second branch is also called an advancer.

In Yorkshire in the United Kingdom roe deer hunting is especially popular due to the large antlers produced there. This is due to the high levels of chalk in Yorkshire. The chalk is high in calcium which is ingested by the deer and helps growth in the antlers.[25]

Shed antler hunting

Gathering shed antlers or "sheds" attracts dedicated practitioners who refer to it colloquially as shed hunting, or bone picking. In the United States, the middle of December to the middle of February is considered shed hunting season, when deer, elk, and moose begin to shed. The North American Shed Hunting Club, founded in 1991, is an organization for those who take part in this activity.[20]

In the United States in 2017 sheds fetch around US$10 per pound, with larger specimens in good condition attracting higher prices. The most desirable antlers have been found soon after being shed. The value is reduced if they have been damaged by weathering or being gnawed by small animals. A matched pair from the same animal is a very desirable find but often antlers are shed separately and may be separated by several miles. Some enthusiasts for shed hunting use trained dogs to assist them.[26] Most hunters will follow 'game trails' (trails where deer frequently run) to find these sheds or they will build a shed trap to collect the loose antlers in the late winter/early spring.

In most US states, the possession of or trade in parts of game animals is subject to some degree of regulation, but the trade in antlers is widely permitted.[27] In the national parks of Canada, the removal of shed antlers is an offense punishable by a maximum fine of C$25,000, as the Canadian government considers antlers to belong to the people of Canada and part of the ecosystems in which they are discarded.[28]

Carving for decorative and tool uses

Antler has been used through history as a material to make tools, weapons, ornaments, and toys.[29] It was an especially important material in the European Late Paleolithic, used by the Magdalenian culture to make carvings and engraved designs on objects such as the so-called Bâton de commandements and the Bison Licking Insect Bite. In the Viking Age and medieval period, it formed an important raw material in the craft of comb-making. In later periods, antler—used as a cheap substitute for ivory—was a material especially associated with equipment for hunting, such as saddles and horse harness, guns and daggers, powder flasks, as well as buttons and the like. The decorative display of wall-mounted pairs of antlers has been popular since medieval times at least.

The Netsilik Inuit people made bows and arrows using antler, reinforced with strands of animal tendons braided to form a cable-backed bow.[30] Several American Indian tribes also used antler to make bows, gluing tendons to the bow instead of tying them as cables. An antler bow, made in the early 19th century, is on display at Brooklyn Museum. Its manufacture is attributed to the Yankton Sioux.[31]

Through history large deer antler from a suitable species (e.g. red deer) were often cut down to its shaft and its lowest tine and used as a one-pointed pickax.[32][33]

Ceremonial roles

Antler headdresses were worn by shamans and other spiritual figures in various cultures, and for dances; 21 antler "frontlets" apparently for wearing on the head, and over 10,000 years old, have been excavated at the English Mesolithic site of Starr Carr. Antlers are still worn in traditional dances such as Yaqui deer dances and carried in the Abbots Bromley Horn Dance.

Dietary usage

In the velvet antler stage, antlers of elk and deer have been used in Asia as a dietary supplement or alternative medicinal substance for more than 2,000 years.[34] Recently, deer antler extract has become popular among Western athletes and body builders because the extract, with its trace amounts of IGF-1, is believed to help build and repair muscle tissue; however, one double-blind study did not find evidence of intended effects.[35][36]

Elk, deer, and moose antlers have also become popular forms of dog chews that owners purchase for their pet canines.

References

- "Arctic Wildlife - Arctic Studies Center". naturalhistory.si.edu. Archived from the original on 1 May 2018. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- Brown, Leslie (1993). The New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, Volume 1. Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-861271-0.

- Harper, Douglas (2010). "Online Etymology Dictionary". Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 8 November 2010. Retrieved 2010-11-08.

- "antler". CollinsDictionary.com. Collins English Dictionary - Complete & Unabridged 11th Edition. Retrieved October 27, 2012. Archived from the original on October 28, 2012.

- "Dictionary.com Unabridged". Dictionary.com. 2010. Archived from the original on 8 November 2010. Retrieved 2010-11-08.

- Hall, Brian K. (2005). "Antlers". Bones and Cartilage: Developmental and Evolutionary Skeletal Biology. Academic Press. pp. 103–114. ISBN 0-12-319060-6. Retrieved 2010-11-08.

- Antlered Doe Archived February 29, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- "Mammals: Pronghorn". San Diego Zoo. Retrieved 2013-06-27.

- Malo, A. F.; Roldan, E. R. S.; Garde, J.; Soler, A. J.; Gomendio, M. (2005). "Antlers honestly advertise sperm production and quality". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 272 (1559): 149–57. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2933. PMC 1634960. PMID 15695205.

- Whitaker, John O.; Hamilton, William J., Jr. (1998). Mammals of the Eastern United States. Cornell University Press. p. 517. ISBN 0-8014-3475-0. Retrieved 2010-11-08.

- Ditchkoff, Stephen S.; Lochmiller, Robert L.; Masters, Ronald E.; Hoofer, Steven R.; Bussche, Ronald A. Van Den (2007). "Major-Histocompatibility-Complex-Associated Variation in Secondary Sexual Traits of White-Tailed Deer (Odocoileus Virginianus): Evidence for Good-Genes Advertisement". Evolution. 55 (3): 616–25. doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2001.tb00794.x. PMID 11327168.

- Gilbert, Clément; Ropiquet, Anne; Hassanin, Alexandre (2006). "Mitochondrial and nuclear phylogenies of Cervidae (Mammalia, Ruminantia): Systematics, morphology, and biogeography". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 40 (1): 101–17. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2006.02.017. PMID 16584894.

- Kruuk, Loeske E. B.; Slate, Jon; Pemberton, Josephine M.; Brotherstone, Sue; Guinness, Fiona; Clutton-Brock, Tim (2002). "Antler Size in Red Deer: Heritability and Selection but No Evolution". Evolution. 56 (8): 1683–95. doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2002.tb01480.x. PMID 12353761. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-09-16.

- Perez-Gonzalez, J.; Carranza, J.; Torres-Porras, J.; Fernandez-Garcia, J. L. (2010). "Low Heterozygosity at Microsatellite Markers in Iberian Red Deer with Small Antlers". Journal of Heredity. 101 (5): 553–61. doi:10.1093/jhered/esq049. PMID 20478822.

- Metz, Matthew C.; Emlen, Douglas J.; Stahler, Daniel R.; MacNulty, Daniel R.; Smith, Douglas W. (2018-09-03). "Predation shapes the evolutionary traits of cervid weapons". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 2 (10): 1619–1625. doi:10.1038/s41559-018-0657-5. PMID 30177803.

- Schaefer and Mahoney (December 2001). "Antlers on Female Caribou: Biogeography of the Bones of Contention". Ecology. 82 (12): 3556–3560. doi:10.2307/2680172. JSTOR 2680172.

- Melnycky; et al. (December 2013). "Scaling of antler size in reindeer (Rangifer tarandus): sexual dimorphism and variability in resource allocation" (PDF). Journal of Mammalogy. 94 (6): 1371–1379. doi:10.1644/12-mamm-a-282.1. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- "Moose as a domestic animal". The Kostroma moose farm. Archived from the original on 2016-12-10.

- Bubenik, George A.; Bubenik, Peter G. (2008). "Palmated antlers of moose may serve as a parabolic reflector of sounds". European Journal of Wildlife Research. 54 (3): 533–5. doi:10.1007/s10344-007-0165-4. Lay summary – The Guardian (March 20, 2008).

- George A. Feldhamer; William J. McShea (26 January 2012). Deer: The Animal Answer Guide. JHU Press. pp. 32–. ISBN 978-1-4214-0387-8.

- Dennis Walrod (2010). Antlers: A Guide to Collecting, Scoring, Mounting, and Carving. Stackpole Books. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-8117-0596-7.

- Bauer, Erwin A.; Bauer, Peggy (2000). Antlers: Nature's Majestic Crown. Voyageur Press. pp. 20–1. ISBN 978-1-61060-343-0.

- Laskow, Sarah. "Antler Farm". Medium (service). Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- "Wildlifeonline - Questions & Answers - Deer". Archived from the original on January 15, 2012. Retrieved March 1, 2012.

- Fieldsports Britain. "Fieldsports Britain : Grouse on the Glorious Twelfth, roebucks and". fieldsportschannel.tv. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- Dennis Walrod (2010). Antlers: A Guide to Collecting, Scoring, Mounting, and Carving. Stackpole Books. pp. 44–52. ISBN 978-0-8117-0596-7.

- Dennis Walrod (2010). Antlers: A Guide to Collecting, Scoring, Mounting, and Carving. Stackpole Books. pp. 46–47. ISBN 978-0-8117-0596-7.

- Susan Quinlan (18 November 2011). "Parks Canada reminds visitors you can look, but don't touch". Prairie Post West. p. 3. Archived from the original on 6 February 2015. Retrieved 5 December 2011.

- Bauer, Erwin A.; Bauer, Peggy (2000). Antlers: Nature's Majestic Crown. Voyageur Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-61060-343-0.

- Balikci, Asen (1989). The Netsilik Inuit. Waveland Press. pp. 38–39.

- "Bow, Bow Case, Arrows and Quiver". Brooklyn Museum.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-03-08. Retrieved 2012-07-06.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-07-25. Retrieved 2011-01-15.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Velvet Antler - Research Summary". www.vitaminsinamerica.com. Archived from the original on 18 October 2017. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- DiSalvo (2015-9-18). How to Squeeze Snake Oil from Deer Antlers and Make Millions. [1] forbes.com

- Sleivert, G; Burke, V; Palmer, C; Walmsley, A; Gerrard, D; Haines, S; Littlejohn, R (2003). "The effects of deer antler velvet extract or powder supplementation on aerobic power, erythropoiesis, and muscular strength and endurance characteristics". International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism. 13 (3): 251–65. doi:10.1123/ijsnem.13.3.251. PMID 14669926.

![]()

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Antlers. |