Vientiane

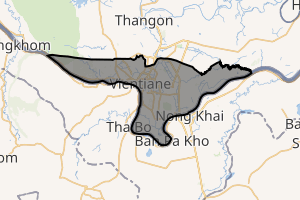

Vientiane (/viˌɛntiˈɑːn/ vi-EN-ti-AHN,[3] French: [vjɛ̃tjan]; Lao: ວຽງຈັນ, Thai: เวียงจันทน์ RTGS: Wīang chan, pronounced [wíəŋ tɕàn], Chinese: 万象) is the capital and largest city of Laos, on the banks of the Mekong River near the border with Thailand. Vientiane became the capital in 1573 due to fears of a Burmese invasion but was later looted then razed to the ground in 1827 by the Siamese (Thai).[4] Vientiane was the administrative capital during French rule and, due to economic growth in recent times, is now the economic center of Laos. The city had a population of 820,000 as at the 2015 Census.

Vientiane | |

|---|---|

Clockwise from top: Temple at That Luang, Haw Phra Kaew, That Dam, That Luang Stupa, Mekong Riverside, Patuxai, Wat Si Saket | |

| |

Vientiane  Vientiane | |

| Coordinates: 17°58′N 102°36′E | |

| Country | |

| Admin. division | Vientiane Prefecture |

| Settled | 9th century[1] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 130 km2 (50 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 174 m (570 ft) |

| Population (2015 Census) | |

| • Total | 820,940[2] |

| Time zone | UTC+7 (ICT) |

Vientiane is noted as the home of the most significant national monument in Laos: That Luang, which is a known symbol of Laos and an icon of Buddhism in Laos. Other significant Buddhist temples in Laos can be found there as well, such as Haw Phra Kaew, which formerly housed the Emerald Buddha.

The city hosted the 25th Southeast Asian Games in December 2009, celebrating 50 years of the Southeast Asian Games.

Etymology

The name of the city is derived from Pali, the liturgical language of Theravada Buddhism. The name Vientiane is a French version of the city's Lao name, Viang Chan, reflecting the difficulty the French had in pronouncing the Lao name.[5] Viang means city (originally, walled settlement).[5] The word chan has multiple potential meanings but is generally believed in this context to refer to sandalwood. Some believe, however, that it means moon.[5][6] This issue exists because the words for "moon" (ຈັນທຣ໌, from Sanskrit चन्द्र candra) and "sandalwood" (ຈັນທນ໌, from Sanskrit चन्दन candana) are written and pronounced identically as ຈັນ chan in modern Lao. Other renderings of the city's name in English include Viangchan,[7] or occasionally Wiangchan.

History

The great Laotian epic, the Phra Lak Phra Lam, claims that Prince Thattaradtha founded the city when he left the legendary Lao kingdom of Muong Inthapatha Maha Nakhone because he was denied the throne in favor of his younger brother. Thattaradtha founded a city called Maha Thani Si Phan Phao on the western banks of the Mekong River; this city was said to have later become today's Udon Thani, Thailand. One day, a seven-headed Naga told Thattaradtha to start a new city on the east bank of the river opposite Maha Thani Si Phan Phao. The prince called this city Chanthabuly Si Sattanakhanahud; which was said to be the predecessor of modern Vientiane.

Contrary to the Phra Lak Phra Lam, most historians believe Vientiane was an early Khmer settlement centered around a Hindu temple, which the Pha That Luang would later replace. In the 11th and 12th centuries, the time when the Lao and Thai people are believed to have entered Southeast Asia from Southern China, the few remaining Khmers in the area were either killed, removed, or assimilated into the Lao civilization, which would soon overtake the area.

In 1354, when Fa Ngum founded the kingdom of Lan Xang.[8]:223 Vientiane became an important administrative city, even though it was not made the capital. King Setthathirath officially established it as the capital of Lan Xang in 1563, to avoid Burmese invasion.[9] When Lan Xang fell apart in 1707, it became an independent Kingdom of Vientiane. In 1779, it was conquered by the Siamese general Phraya Chakri and made a vassal of Siam.

When King Anouvong raised an unsuccessful rebellion, it was obliterated by Siamese armies in 1827. The city was burned to the ground and was looted of nearly all Laotian artifacts, including Buddha statues and people. Vientiane was in great disrepair, depopulated and disappearing into the forest, when the French arrived. It eventually passed to French rule in 1893. It became the capital of the French protectorate of Laos in 1899. The French rebuilt the city and rebuilt or repaired Buddhist temples such as Pha That Luang, Haw Phra Kaew, and left many colonial buildings behind. During French rule, the Vietnamese were encouraged to migrate to Laos, which resulted in 53% of the population of Vientiane being Vietnamese in the year of 1943.[10] As late as 1945, the French drew up an ambitious plan to move massive Vietnamese population to three key areas, i.e. the Vientiane Plain, Savannakhet region, Bolaven Plateau, which was only discarded by Japanese invasion of Indochina.[10] If this plan had been implemented, according to Martin Stuart-Fox, the Lao might well have lost control over their own country.[10]

During World War II, Vientiane fell with little resistance and was occupied by Japanese forces, under the command of Sako Masanori.[11] On 9 March 1945 French paratroopers arrived, and reoccupied the city on 24 April 1945.[12]

As the Laotian Civil War broke out between the Royal Lao Government and the Pathet Lao, Vientiane became unstable. In August 1960, Kong Le seized the capital and insisted that Souvanna Phouma become prime minister. In mid-December, Phoumi Nosavan then seized the capital, overthrew the Phouma Government, and installed Boun Oum as prime minister. In mid-1975, Pathet Lao troops moved towards the city and Americans began evacuating the capital. On 23 August 1975, a contingent of 50 Pathet Lao women symbolically liberated the city.[12] On 2 December 1975, the communist party of the Pathet Lao took over Vientiane, defeated the Kingdom of Laos, and renamed the country the Lao People's Democratic Republic, which ended the Laotian Civil War. The next day, an Insurgency in Laos began in the jungle, with the Pathet Lao fighting factions of Hmong and royalists.

Vientiane was the host of the incident-free 2009 Southeast Asian Games. Eighteen competitions were dropped from the previous games held in Thailand, due to Laos' landlocked borders and the lack of adequate facilities in Vientiane.

Geography and climate

Geography

Vientiane is on a bend of the Mekong River, at which point it forms the border with Thailand.

Climate

Vientiane features a tropical savanna climate (Köppen Aw) with a distinct wet season and a dry season. Vientiane's dry season spans from November through March. April marks the onset of the wet season which in Vientiane lasts about seven months. Vientiane tends to be very hot and humid throughout the course of the year, though temperatures in the city tend to be somewhat cooler during the dry season than the wet season.

| Climate data for Vientiane | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 35.6 (96.1) |

37.8 (100.0) |

40.0 (104.0) |

41.1 (106.0) |

38.9 (102.0) |

37.8 (100.0) |

36.1 (97.0) |

37.2 (99.0) |

38.9 (102.0) |

38.9 (102.0) |

34.4 (93.9) |

33.4 (92.1) |

41.1 (106.0) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 28.4 (83.1) |

30.3 (86.5) |

33.0 (91.4) |

34.3 (93.7) |

33.0 (91.4) |

31.9 (89.4) |

31.3 (88.3) |

30.8 (87.4) |

30.9 (87.6) |

30.8 (87.4) |

29.8 (85.6) |

28.1 (82.6) |

31.1 (88.0) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 16.4 (61.5) |

18.5 (65.3) |

21.5 (70.7) |

23.8 (74.8) |

24.6 (76.3) |

24.9 (76.8) |

24.7 (76.5) |

24.6 (76.3) |

24.1 (75.4) |

22.9 (73.2) |

19.3 (66.7) |

16.7 (62.1) |

21.8 (71.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 0.0 (32.0) |

7.6 (45.7) |

12.1 (53.8) |

17.1 (62.8) |

20.0 (68.0) |

21.1 (70.0) |

21.2 (70.2) |

21.1 (70.0) |

21.2 (70.2) |

12.9 (55.2) |

8.9 (48.0) |

5.0 (41.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 7.5 (0.30) |

13.0 (0.51) |

33.7 (1.33) |

84.9 (3.34) |

245.8 (9.68) |

279.8 (11.02) |

272.3 (10.72) |

334.6 (13.17) |

297.3 (11.70) |

78.0 (3.07) |

11.1 (0.44) |

2.5 (0.10) |

1,660.5 (65.37) |

| Average rainy days | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 15 | 18 | 20 | 21 | 17 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 118 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 70 | 68 | 66 | 69 | 78 | 82 | 82 | 84 | 83 | 78 | 72 | 70 | 75 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 254.4 | 214.3 | 216.8 | 226.3 | 207.1 | 152.9 | 148.6 | 137.1 | 137.7 | 247.7 | 234.3 | 257.5 | 2,434.7 |

| Source 1: World Meteorological Organization,[13] Deutscher Wetterdienst (extremes 1907–1990)[14] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (sun and humidity)[15] | |||||||||||||

Tourism

Although still a small city, the capital attracts many tourists. The city contains many temples and Buddhist monuments. A popular attraction for foreign visitors is Pha That Luang, an important national cultural monument of Laos and one of its best known stupas. It was originally built in 1566 by King Setthathirath, and was restored in 1953. The golden stupa is 45 metres tall and is believed to contain a relic of the Lord Buddha.[16]

Another site that is also popular amongst tourists is Wat Si Muang. The temple was built on the ruins of a Khmer Hindu shrine, the remains of which can be seen behind the ordination hall.[17] It was built in 1563 and is believed to be guarded by the spirit of a local girl, Nang Si. Legend tells that Nang Si, who was pregnant at the time, leapt to her death as a sacrifice, just as the pillar was being lowered into the hole. In front of the temple stands a statue of King Sisavang Vong.[17]

The memorial monument, Patuxai, built between 1957 and 1968, is perhaps the most prominent landmark in the city.[16] While the Arc de Triomphe in Paris inspired the architecture, the design incorporates typical Lao motifs including Kinnari, a mythical bird woman. Energetic visitors can climb to the top of the monument for a panoramic view of the city.

Buddha Park was built in 1958 by Luang Pu Bunleua Sulilat and contains a collection of Buddhist and Hindu sculptures, scattered amongst gardens and trees. The park is 28 kilometres south of Vientiane at the edge of the Mekong River.[18]

Vientiane is home to one of the three bowling alleys in Laos (the other two are in Luang Prabang and Pakse).

Other sites include:

- Haw Phra Kaew, former temple, now museum and small shops

- Lao National Museum

- Kaysone Phomvihane Museum

- Talat Sao Morning market

- That Dam, large stupa

- Wat Ong Teu Mahawihan, Buddhist monastery

- Wat Sri Chomphu Ong Tue, Buddhist temple

- Wat Si Saket, Buddhist wat

- Wat Sok Pa Luang, Buddhist temple

- Settha Palace Hotel, established 1932

- The Sanjiang Market[19]

Colleges and universities

The National University of Laos, one of three universities in the country, is in Vientiane.[20]

Broadcasting

- Lao National Radio has a large mediumwave transmitter with a 277-metre guyed mast at 18° 20' 33"N, 102° 27' 01"E.

- China Radio International (CRI) FM 93.0.[21]

Economy

Vientiane is the driving force behind economic change in Laos. In recent years, the city has experienced rapid economic growth from foreign investment.[22] In 2011, the stock exchange opened with two listed company stocks, with the cooperation of South Korea.[23]

Transportation

Within Laos

There are regular bus services connecting Vientiane Bus Station with the rest of the country. In Vientiane, regular bus services around the city are provided by Vientiane Capital State Bus Enterprise.[24] Vientiane will have metro system that are currently in the feasibility study being conducted by China Railway Construction Corporation.

From Thailand

The First Thai-Lao Friendship Bridge, built in the 1990s, crosses the river 18 kilometres downstream of the city of Nong Khai in Thailand, and is the major crossing between the two countries. The official name of the bridge was changed in 2007 by the addition of "First", after the Second Friendship Bridge linking Mukdahan in Thailand with Savannakhet in Laos was opened early in 2007.

A metre gauge railway link over the bridge was formally inaugurated on 5 March 2009, ending at Thanaleng Railway Station, in Dongphosy village (Vientiane Prefecture), 20 km east of Vientiane.[26][27] As of November 2010, Lao officials plan to convert the station into a rail cargo terminal for freight trains, allowing cargo to be transported from Bangkok into Laos at a lower cost than would be possible with road transport.[28]

To Thailand

Daily non-stop bus services run between Vientiane and Nong Khai, Udon Thani, and Khon Kaen.

From China

In October 2010, plans were announced for a 530 km high-speed railway linking Vientiane to Xishuangbanna, in Yunnan Province in China.[29] which was later modified to a high speed train from the border town of Boten to Vientiane, with total distance of 421.243 km, to be served by 21 stations, including 5 major stations, passing through 165 bridges (total length of 92.6 km) and 69 tunnels (total length of 186.9 km)[30][31] Construction on this line, as part of the longer Kunming to Singapore Railway, began on 25 April 2011.[32]

By air

Vientiane is served by Wattay International Airport with international connections to other Asian countries. Lao Airlines has regular flights to several domestic destinations in the country (including several flights daily to Luang Prabang, plus a few flights weekly to other local destinations).[33] In Thailand, Udon Thani International Airport, one of Wattay's main connections, is less than 90 km distant.

Healthcare

The "Centre Medical de l'Ambassade de France" is available to the foreign community in Laos. The Mahosot Hospital is an important local hospital in treating and researching diseases and is connected with the University of Oxford. In 2011 the Alliance Clinic opened near the airport, with a connection to Thai hospitals. The Setthathirat International Clinic has foreign doctors. A free, 24/7 ambulance service is provided by Vientiane Rescue, a volunteer-run rescue service established in 2010.[34]

References

- Lao Statistics Bureau (21 October 2016). "Results of Population and Housing Census 2015" (PDF). Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- United Nations Statistics Division. "Population by sex, rate of population increase, surface area and density" (PDF). Retrieved 9 November 2007.

- Wells, John (3 April 2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Pearson Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- "Vientiane". Farlex Encyclopedia. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- Askew, Marc; Long, Colin; Logan, William (2006). Vientiane: Transformations of a Lao Landscape. Routledge. pp. 15, 46. ISBN 978-1-134-32365-4.

- Goscha, Christopher E.; Ivarsson, Søren (2003). Contesting Visions of the Lao Past: Laos Historiography at the Crossroads. NIAS Press. pp. 34 n.62, 204 n.18. ISBN 978-87-91114-02-1.

- "Definition of 'Viangchan'". Collins English Dictionary. Glasgow: HarperCollins. Archived from the original on 11 June 2019. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

Viangchan in British. (ˌwiːɛŋˌtæn). noun: another spelling of Vientiane

- Coedès, George (1968). Walter F. Vella (ed.). The Indianized States of Southeast Asia. trans.Susan Brown Cowing. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1.

- "Vientiane marks 450 years anniversary". Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- Stuart-Fox, Martin (1997). A History of Laos. Cambridge University Press, p. 51. ISBN 978-0-521-59746-3.

- "Far East and Australasia". Archived from the original on 21 November 2010. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- Far East and Australasia 2003 - Google Books

- "World Weather Information Service - Vientiane (1951-2000)". World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- "Klimatafel von Vientiane (Viangchan) / Laos" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961-1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- "Vientiane Climate Normals 1961−1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- Lao National Tourism Administration - Tourist Sites in Vientiane Capital Archived 23 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "Wat Si Muang". Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- "Buddha Park - Vientiane - Laos - Asia for Visitors". Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- "China Gives Southeast Asia's Poorest First Time Access to Consumer Goods - China Briefing News". China Briefing News.

- "National University of Laos (NUOL)". National University of Laos (NUOL). NUOL. Retrieved 8 December 2014.

- "China Radio International".

- Work begins on major new Vientiane shopping centre | Lao Voices Archived 3 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "Laos stocks soar on debut – yes, both of them". Financial Times.

- "Timetables". Vientiane Capital State Bus Enterprise. VCSBE. Retrieved 8 December 2014.

- Matthias Gasnier (13 August 2012). "Laos 2012 Update: Chinese models keep spreading". bestsellingcarsblog.com. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- "Inaugural train begins Laos royal visit". Railway Gazette International. 5 March 2009.

- Andrew Spooner (27 February 2009). "First train to Laos". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- Rapeepat Mantanarat (9 November 2010). "Laos rethinks rail project". TTR Weekly. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- "New China-Laos link". Railways Africa. Archived from the original on 31 January 2014. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- "Boten Vientiane Railway Link". Laos-Travel-Guide. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 18 January 2011.

- "中国铁路考察团对中老铁路进行全线考察 | China Railway Erju Group Corporation (中铁二局集团公司)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 25 December 2010.

- "Kunming-Singapore High-Speed Railway begins construction". People's Daily. 25 April 2011. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- "Route Map". Lao Airlines. Lao Airlines. Retrieved 8 December 2014.

- "About". Vientiane Rescue. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

Further reading

- Askew, Marc, William Stewart Logan, and Colin Long. Vientiane: Transformations of a Lao Landscape. London: Routledge, 2007. ISBN 978-0-415-33141-8

- Sharifi et al., Can master planning control and regulate urban growth in Vientiane, Laos?. Landscape and Urban Planning, 2014. DOI: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2014.07.014

- Flores, Penelope V. Good-Bye, Vientiane: Untold Stories of Filipinos in Laos. San Francisco, CA: Philippine American Writers and Artists, Inc, 2005. ISBN 978-0-9763316-1-2

- Renaut, Thomas, and Arnaud Dubus. Eternal Vientiane. City heritage. Hong Kong: Published by Fortune Image Ltd. for Les Editions d'Indochine, 1995.

- Schrama, Ilse, and Birgit Schrama. Buddhist Temple Life in Laos: Wat Sok Pa Luang". Bangkok: Orchid Press, 2006. ISBN 978-974-524-073-5

- Women's International Group Laos. Vientiane Guide. Vientiane: Women's International Group, 1993.