Lee Lawrie

Lee Oscar Lawrie (October 16, 1877 – January 23, 1963[1]) was one of the United States' foremost architectural sculptors and a key figure in the American art scene preceding World War II. Over his long career of more than 300 commissions Lawrie's style evolved through Modern Gothic, to Beaux-Arts, Classicism, and, finally, into Moderne or Art Deco.

Lee Oscar Lawrie | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | October 16, 1877 Rixdorf, Germany |

| Died | January 23, 1963 (aged 85) Easton, Maryland, United States |

| Nationality | German-American |

| Alma mater | Yale University |

| Known for | Sculptor |

Notable work | Atlas in collaboration with Rene Paul Chambellan |

| Style | Gothic, Beaux-Arts, Classicism, Art Deco |

He created a frieze on the Nebraska State Capitol building in Lincoln, Nebraska, including a portrayal of the announcement of the Emancipation Proclamation. He also created some of the architectural sculpture and his most prominent work, the free-standing bronze Atlas (installed 1937) at New York City's Rockefeller Center.[2]

Lawrie's work is associated with some of the United States' most noted buildings of the first half of the twentieth century. His stylistic approach evolved with building styles that ranged from Beaux-Arts to neo-Gothic to Art Deco. Many of his architectural sculptures were completed for buildings by Bertram Goodhue of Cram & Goodhue, including the chapel at West Point; the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, D.C.; the Nebraska State Capitol; the Los Angeles Public Library; St. Bartholomew's Episcopal Church in New York; Cornell Law School in Ithaca, New York; and Rockefeller Chapel at the University of Chicago. He completed numerous pieces in Washington, D.C., including the bronze doors of the John Adams Building of the Library of Congress, the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception south entrance portal, and the interior sculpture of George Washington at the National Cathedral.[3]

Early work

Lee Lawrie was born in Rixdorf, Germany, in 1877 and immigrated to the United States in 1882 as a young child with his family; they settled in Chicago. It was there, at the age of 14, that he began working for the sculptor Richard Henry Park.

At the age of 15, in 1892 Lawrie worked as an assistant to many of the sculptors in Chicago, for their part in constructing the "White City" for the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893. Following the completion of that work, Lawrie went East, where he became an assistant to William Ordway Partridge. During the next decade, he worked with other established sculptors: Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Philip Martiny, Alexander Phimister Proctor, John William Kitson and others. His work at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, St Louis, 1904, under Karl Bitter, the foremost architectural sculptor of the time, allowed Lawrie to develop both his skills and his reputation as an architectural sculptor.

Lawrie received a bachelor's degree in fine arts from Yale University in 1910. He was an instructor in Yale's School of Fine Arts from 1908 to 1919 and taught in the architecture program at Harvard University from 1910 to 1912.[4]

Collaborations with Cram and Goodhue

Lawrie's collaborations with Ralph Adams Cram and Bertram Goodhue brought him to the forefront of architectural sculptors in the United States. After the breakup of the Cram, Goodhue firm in 1914, Lawrie continued to work with Goodhue until the architect died in 1924. He next worked with Goodhue's successors.

Lawrie sculpted numerous bas reliefs for El Fureidis,[5] an estate in Montecito, California designed by Goodhue. The bas reliefs depict the Arthurian Legends and remain intact at the estate today.

The Nebraska State Capitol and the Los Angeles Public Library both feature extensive sculptural programs integrated with the surface, massing, spatial grammar, and social function of the building. Lawrie's collaborations with Goodhue are arguably the most highly developed example of architectural sculpture in American architectural history.

Lawrie served as a consultant to the 1933-34 Century of Progress International Exposition in Chicago. He was a member of the National Institute of Arts and Letters, the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the National Academy of Design, and the Architectural League of New York. Among his many awards was the AIA Gold Medal of the American Institute of Architects in 1921 and 1927, a medal of honor from the Architectural League of New York in 1931, and an honorary degree from Yale University. He served on the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts in Washington, DC from 1933 to 1937 and again from 1945 to 1950; it oversees federal public works and artwork in the city.[6]

Commissions related to Goodhue

- Marble reliefs above the windows of the Deborah Cook Sayles Public Library, Pawtucket, Rhode Island, 1902 (Cram, Goodhue & Ferguson)[7][8]

- Chapel at West Point, West Point, New York (Cram and Goodhue)

- Church of St. Vincent Ferrer, New York City (Cram and Goodhue)

- Pulpit and Lectern and Apse carvings at St. Bartholomew's Episcopal Church, (Cram and Goodhue)

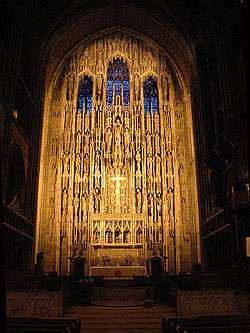

- reredos at Saint Thomas Church on Fifth Avenue in New York City (Cram and Goodhue)

- reredos at St. John's Episcopal Church (West Hartford, Connecticut) (Goodhue)

- Nebraska State Capitol, Lincoln, Nebraska (Goodhue)

- Los Angeles Public Library, Los Angeles, California (Goodhue)

- Trinity English Lutheran Church, Fort Wayne, Indiana (Goodhue)

- National Academy of Sciences Building in Washington, D.C. (Goodhue)

- Rockefeller Chapel, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois (Goodhue)

- Christ Church Cranbrook, in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan (Goodhue)

- Church of the Heavenly Rest, New York City (Mayers Murray & Phillip)

Commissions after Goodhue's death

Rockefeller Center

After Goodhue's death, Lawrie produced important and highly visible work under Raymond Hood at Rockefeller Center in New York City, which included the Atlas in collaboration with Rene Paul Chambellan. By November 1931 Hood said, "There has been entirely too much talk about the collaboration of architect, painter and sculptor." He relegated Lawrie to the role of a decorator.[9]

Lawrie's most noted work is not architectural: it is the freestanding statue of Atlas, on Fifth Avenue at Rockefeller Center, standing a total 45 feet tall, with a 15-foot human figure supporting an armillary sphere.[10] At its unveiling, some critics were reminded of Benito Mussolini, while James Montgomery Flagg suggested that it looked as Mussolini thought he looked.[11] The international character of Streamline Moderne, embraced by Fascism as well as corporate democracy, lost favor during the Second World War.

Featured above the entrance to 30 Rockefeller Plaza and axially behind the golden Prometheus, Lawrie's Wisdom is one of the most visible works of art in the complex. An Art Deco piece, it echoes the statements of power shown in Atlas and Paul Manship's Prometheus.

Other commissions

- Allegorical relief panels called Courage, Patriotism and Wisdom over the entry doors to United States Senate chamber (done as part of the 1950 Federal-period remodeling of the Senate), Washington, D.C.

- Education Building (a.k.a. Forum Building) in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania

- Louisiana State Capitol in Baton Rouge, Louisiana

- Peace Memorial at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

- sculptural elements of the Fidelity Mutual Life Building in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (now Perelman Building of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, including the owl of wisdom, the dog of fidelity, the pelican of charity, the possum of protection, and the squirrel of frugality), architects Zantzinger, Borie and Medary

- Statue of George Washington, National Cathedral, Washington, D.C.

- Friezes for the Ramsey County Courthouse in Saint Paul, Minnesota

- Whatsoever a Man Soweth, fifth issue of the long running Society of Medalists.

- Two Egyptian bas-reliefs for the 1924 Hale Solar Laboratory in Pasadena, California

- National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception and the bronze doors of the John Adams Building at the Library of Congress Annex, both in Washington, D.C.

- Harkness Memorial Tower at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut

- Sterling Memorial Library at Yale University

- Beaumont Tower at Michigan State University in East Lansing, Michigan

- Kirk in the Hills Presbyterian in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

- Bok Singing Tower in Mountain Lake, Florida, architects Zantzinger, Borie and Medary

- Designed sculptures for the Brittany American Cemetery and Memorial in Brittany, France, executed by Jean Juge of Paris and the French sculptor, Augustine Beggi.

- Hubbard Bell Grossman Pillot Memorial gravestone.

- World War I Memorial Flagstaff, Pasadena, California[12]

- Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Bridge, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, 1930[13]

In popular culture

His Atlas was featured on the cover of The New Yorker magazine for December 20 and 27, 2010.

Gallery

- Works by Lawrie

George Washington statue - National Cathedral, Washington, DC

George Washington statue - National Cathedral, Washington, DC Hubbard Bell Grossman Pillot Memorial, Rock Creek Cemetery, Washington, DC

Hubbard Bell Grossman Pillot Memorial, Rock Creek Cemetery, Washington, DC Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Bridge, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, (1930)

Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Bridge, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, (1930)

- Bronze doors of the John Adams Building

East doors, Library of Congress John Adams Building (1939)

East doors, Library of Congress John Adams Building (1939)

Sculpted bronze figures of Odin and Quetzalcoatl (1939)

Sculpted bronze figures of Odin and Quetzalcoatl (1939)

Sculpted bronze figures of Cangjie (1939)

Sculpted bronze figures of Cangjie (1939)

See also

- Edward Ardolino, collaborating sculptor

- List of Saltus Award winners

Notes and references

Notes

- "Lee Lawrie, 85, Is Dead;Sculptor of Statue of Atlas" The New York Times, January 25, 1963

- UPI, "Atlas statue to get makeover in New York", NewsTrack, 4 May 2005

- Civic Art: A Centennial History of the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Commission of Fine Arts, 2013)

- Civic Art: A Centennial History of the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts

- http://www.montecitoparadise.com

- Thomas E. Luebke, ed., Civic Art: A Centennial History of the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Commission of Fine Arts, 2013): Appendix b, p. 548.

- Morgan, William (14 February 2019). "5 gems of Rhode Island architecture". The Providence Journal. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- "Sayles Library Reliefs by Lee Lawrie". Pawtucket Public Art. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

The reliefs represent the first ever commission won by Lawrie

- "'Wisdom with Sound and Light' by Lee Lawrie". Museum Planet. Archived from the original on 2012-09-06. Retrieved 2008-11-25.

- Dianne L. Durante, Outdoor Monuments of Manhattan: A Historical Guide 2007:139ff.

- Durante 2007:141 offers this and some further negative quotes from artists and critics in New York during the forties.

- visited and photographed, September 2012

- Lawrie, Lee, Lee Lawrie: Sculpture, J.H. Jansen, Cleveland, Ohio, 1936, Plate 6

References

- Bok, Edward W., America's Taj Mahal: The Singing Tower of Florida, The Georgia Marble Company, Tate, Georgia c. 1929.

- Brown, Elinor L., Architectural Wonder of the World, State of Nebraska, Building Division, Lincoln, Nebraska 1978.

- Fowler, Charles F., Building a Landmark: The Capitol of Nebraska, Nebraska State Building Division, 1981.

- Garvey, Timothy Joseph, Lee Lawrie: Classicism and American Culture, 1919 - 1954, PhD. Thesis University of Minnesota 1980.

- Gebhard, David, The National Trust Guide to Art Deco in America, John Wiley & Sons, New York, New York 1996.

- Kvaran & Lockley, Guide to Architectural Sculpture of America, unpublished manuscript.

- Lawrie; Lee, Sculpture - 48 Plates With a Foreword by the Sculptor, J.H. Hanson Cleveland, Ohio 1936.

- Luebke, Frederick C. Editor, A Harmony of the Arts: The Nebraska State Capitol, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, Nebraska 1990.

- Masters, Magaret Dale, Hartley Burr Alexander—Writer-In-Stone, Margaret Dale Masters 1992 .

- Nelson, Paul D., Courthouse Sculptor: Lee Lawrie, Ramsey County History Quarterly V43 #4, *Ramsey County Historical Society, St Paul, MN, 2009.

- Oliver, Richard, Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue, The Architectural History Foundation, New York & The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts 1985.

- Whitaker, Charles Harris, Editor, Text by Lee Lawrie et al. Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue, Architect-and Master of Many Arts, Press of the American Institute of Architects, Inc., NYC 1925.

- Whitaker, Charles Harris and Hartley Burr Alexander, The Architectural Sculpture of the State Capitol at Lincoln Nebraska, Press of the American Institute of Architects, New York 1926.

External links

- LeeLawrie.com - Additional Website of Gregory Paul Harm. Features additional Lawrie works recently added by Harm to the Smithsonian Institution's Art Inventory Catalog.

- Lee Lawrie - Stalking Lawrie: America's Machine Age Michelangelo.

- Lee Lawrie page on philart.net - pictures of artistic details on the Perelman building

- Article on Greg Harm's research and discoveries about Lawrie and his work on the Nebraska State Capitol

- Lawrie collection in process. Held by the Department of Drawings & Archives, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University.