Palmette

The palmette is a motif in decorative art which, in its most characteristic expression, resembles the fan-shaped leaves of a palm tree. It has a far-reaching history, originating in ancient Egypt with a subsequent development through the art of most of Eurasia, often in forms that bear relatively little resemblance to the original. In ancient Greek and Roman uses it is also known as the anthemion (from the Greek ανθέμιον, a flower). It is found in most artistic media, but especially as an architectural ornament, whether carved or painted, and painted on ceramics. It is very often a component of the design of a frieze or border. The complex evolution of the palmette was first traced by Alois Riegl in his Stilfragen of 1893. The half-palmette, bisected vertically, is also a very common motif, found in many mutated and vestigial forms, and especially important in the development of plant-based scroll ornament.

_(14597671860).jpg)

.jpg)

Description

The essence of the palmette is a symmetrical group of spreading "fronds" that spread out from a single base, normally widening as they go out, before ending at a rounded or fairly blunt pointed tip. There may be a central frond that is larger than the rest. The number of fronds is variable, but typically between five and about fifteen.

In the repeated border design commonly referred to as anthemion the palm fronds more closely resemble petals of the honeysuckle flower, as if designed to attract fertilizing insects. Some compare the shape to an open hamsa[1] hand – explaining the commonality and derivation of the 'palm' of the hand.

In some forms of the motif the volutes or scrolls resemble a pair of eyes, like those on the harmika[2] of the Tibetan or Nepalese stupa and the eyes and sun-disk[3] at the crown of Egyptian stelae.

In some variants the features of a more fully developed face[3] become discernible in the palmette itself, while in certain architectural uses, usually at the head of pilasters or herms, the fan of palm-fronds transforms into a male or female face and the volutes sometimes appear as breasts. Common to all these forms is the pair of volutes at the base of the fan – constituting the defining characteristics of the palmette.

Evolution

It is thought that the palmette originated in ancient Egypt 2,500 years BC,[4] and has influenced Greek art. Egyptian palmettes (Greek anthemia) were originally based on features of various flowers, including the papyrus and the lotus or lily representing lower and upper Egypt and their fertile union, before it became associated with the palm tree. From earliest times there was a strong association with the sun and it is probably an early form of the halo. Among the oldest forms of the palmette in ancient Egypt was a 'rosette' or daisy-like lotus flower[5] emerging from a 'V' of foliage or petals resembling the akhet hieroglyph depicting the setting or rising sun at the point where it touches the two mountains of the horizon – 'dying', being 'reborn' and giving life to the earth. A second form, apparently evolved from this, is a more fully developed palmette[6] similar to the forms found in Ancient Greece.

Third is a version consisting of a clump of lotus or papyrus blooms on tall stems, with a drooping bud or flower on either side, arising from a (primal) swamp. The lotus and papyrus clump occur in association with Hapy, the god of the crucial life-giving annual Nile inundation, who binds their stems together around an offering table in the sema-tawi motif – itself echoing the shapes of the 'akhet' of the horizon. This unification scene appeared on the base of the throne of several kings, who were thought of as preserving the union of the two lands of (upper and lower, but also physical and spiritual) Egypt and thereby mastering the forces of renewal. These 'binding' scenes, and the heliotropic swamp plants appearing in them, evoked the necessity of discerning and revealing the underlying harmony, the origin of all manifest forms, that re-connects the dispersed and separate-seeming fragments of everyday experience. The further implication is that it is from this apparently occult and magical, undivided source that fertility and new life spring.

Another variant of this motif is a single lotus bloom between two upright buds, a favourite fragrant offering. The god of fragrance, Nefertem,[7] is represented by such a lotus, or is shown bearing a lotus as his crown. The lotus in Nefertem's head dress typically incorporates twin 'menats'[8] or necklace counterpoises (commonly said to represent fertility) hanging down from the base of the flower on either side of the stem, recalling the symmetrically drooping pair of stems in the lotus and papyrus clumps mentioned above. Curiously, when depicted on Egyptian tomb walls and in formalized garden scenes,[9] date palms are invariably shown in a similar stylistic convention with a cluster of dates hanging down on either side below the crown in this same position. The link between these hanging clusters and the volutes of the palmette is visually clear, but remains inexplicit. Rising and setting sun and opening and closing lotus are linked by the Osiris legend to day and night, life and death and the nightly ordeal of the setting sun to be swallowed by night-sky goddess Nut, to pass through the Duat ("underworld") and be born anew each morning.[10] The plants depicted with this solar fan of fronds or petals and 'supported' by pairs of pendant blooms, buds or fruit clusters all seem especially to emulate and share in the sun's sacrificial cycle of death and rebirth and to point to the lessons it holds for mankind. It seems likely that the underlying model for all these fertile shapes, echoed by the curling cows-horn wig and sistrum-volutes of maternity-goddess Hathor, was the womb, with the twin egg-clusters of its ovaries. When the sun is reborn in the morning it is said to be born from the womb of Nut. The stylized palmette-forms of the lotus and papyrus showing the solar rosette or daisy-wheel emerging from the volutes of the calyx are similar magical enactments of the 'akhet' – this sacred moment of enhanced creation, the act of transcending or surpassing one's mortal form and 'going forth by day' as an akh or higher, winged, shining, all-encompassing and all-seeing form of life.

Most early Egyptian forms of the motif appear later in Crete, Mesopotamia, Assyria and Ancient Persia, including the daisy-wheel-style lotus and bud border.[11] In the form of the palmette that appears most frequently on Greek pottery,[12] often interspersed with scenes of heroic deeds, the same motif is bound within a leaf-shaped or lotus-bud shaped outer line. The outer line can be seen to have evolved from an alternating frieze of stylized lotus and palmette.[13] This anticipates the form it often took – from Renaissance sculpture through to Baroque fountains – of the inside of a half scallop shell, in which the palm fronds have become the fan of the shell and the scrolls remain at the convergence of the fan. Here the shape was associated with Venus or Neptune and was typically flanked by a pair of dolphins or became a vehicle drawn by sea-horses. Later, this circular or oval outer line became a motif in itself, forming an open C-shape with the two in-growing scrolls at its tips. Much Baroque and Rococo furniture, stucco ornament or wrought-iron work of gates and balconies is made up of ever-varying combinations these C-scrolls, either on their own, back to back, or in support of full palmettes.

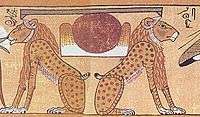

The hieroglyph akhet of the horizon guarded by the twin lions of Aker

The hieroglyph akhet of the horizon guarded by the twin lions of Aker Hapy, god of the Nile inundation: by making offerings and ensuring that Upper and Lower Egypt remain unified, the Pharaoh helps to guarantee that the annual flood of the Nile will recur

Hapy, god of the Nile inundation: by making offerings and ensuring that Upper and Lower Egypt remain unified, the Pharaoh helps to guarantee that the annual flood of the Nile will recur

Classical architecture

As an ornamental motif found in classical architecture, the palmette and anthemion[14] take many and varied forms.[15] Typically, the upper part of the motif consists of five or more leaves or petals fanning rhythmically upwards from a single triangular or lozenge-shaped source at the base. In some instances fruits resembling palm fruits hang down on either side above the base and below the lowest leaves. The lower part consists of a symmetrical pair of elegant 'S' scrolls or volutes curling out sideways and downwards from the base of the leaves. The upper part recalls the thrusting growth of leaves and flowers, while the volutes of the lower part seem to suggest both contributing fertile energies and resulting fruits. It is often present on the necking of the capital of Ionic order columns; however in column capitals of the Corinthian order it takes the shape of a 'fleuron' or flower resting against the abacus (top-most slab) of the capital and springing out from a pair of volutes which, in some versions, give rise to the elaborate volutes and acanthus ornament of the capital.

Botanical combinations

_MET_DP21014_(cropped).jpg)

According to Boardman, although lotus friezes or palmette friezes were known in Mesopotamia centuries before, the unnatural combination of various botanical elements which have no relationship in the wild, such as the palmette, the lotus and sometimes rosette flowers, is a purely Greek innovation, which was then adopted on a very broad geographical scale throughout the Hellenistic world.[16]

Hellenistic "Flame palmettes"

From the 5th century, palmettes tended to have sharply splaying leaves. From the 4th century however, the end of the leaves tend to turn in, forming what is called the "flame palmette" design. This is the design that was adopted in Hellenistic architecture and became very popular on a wide geographical scale. This is the design that was adopted by India in the 3rd century BC for some of its sculptural friezes, such as on the abaci of the Pillars of Ashoka, or the central design of the Pataliputra capital, probably through the Seleucid Empire or Hellenistic cities such as Ai-Khanoum.[17]

Usage

In classical architecture the motif had specific uses, including:

- the fronts of ante-fixae,

- acroteria

- the upper portion of the stele or vertical tombstones,

- the necking of the Ionic columns of the Erechtheum and its continuation as a decorative frieze on the walls of the same, and

- the cymatium of a cornice.[18]

Variants and related motifs

The palmette is related to a range of motifs in differing cultures and periods. In ancient Egypt palmette motifs existed both as a form of flower and as a stylized tree, often referred to as a Tree of life. Other examples from ancient Egypt are the alternating lotus flower and bud border[19] designs, the winged disk of Horus with its pair of Uraeus serpents, the Eye of Horus and curve-topped commemorative stele. In later Assyrian versions of the Tree of Life, the feathered falcon wings of the Egyptian winged disk[20] have become associated with the fronds of the palm tree. Similar lotus flower and bud borders, closely associated with palmettes and rosettes, also appeared in Mesopotamia. There appears to be an equivalence between the horns of horned creatures, the wings of winged beings[21] including angels, griffins and sphinxes and both the fan and the volutes of the palmette; there is also an underlying 'V' shape in each of these forms that parallels the association of the palm itself with victory, energy and optimism.

An image of Nike, winged goddess of victory, from an Attic vase of the 6th century BC (see gallery), shows how the sacrificial offering alluded to by the voluted altar and flame, the wings of the goddess and the victory being celebrated, all resonate with the same multiple underlying associations carried within the component forms of the palmette motif. Similar forms are found in the hovering winged disc and sacred trees[22] of Mesopotamia, the caduceus wand of Hermes, the ubiquitous scrolled scallop shells in the canopy of the Renaissance sculptural niche, originating in Greek and Roman sarcophagi, echoed above theatrical proscenium arches[23] and on the doors, windows, wrought iron gates and balconies[24] of palaces and grand houses; the shell-like fanlight over the door in Georgian[25] and similar urban architecture, the gul[26] and[27] boteh motifs of Central Asian carpets and textiles, the trident of Neptune/Poseidon, both the trident and lingam of Shiva, the 'bai sema' lotus-petal-shaped boundary markers of the Thai inner-temple, Vishnu's mount, Garuda,[28] the vajra thunderbolt,[29] diamond mace or enlightenment jewel-in-the-lotus of Tibet and South-East Asia, the symmetrically scrolled cloud and bat[30] motifs and the similarly scrolled ruyi[31] or ju-i scepter and lingzhi[32] or fungus of longevity of the Chinese tradition. Both as a form of the lotus rising from the swamps to touch the sun and as a (palm) tree reaching from earth to heaven, the palmette carries the characteristics of the axis mundi or world tree. The fleur-de-lis, which became a potent and enigmatic emblem of the divine right of kings, said to have been bestowed on early French kings by an angel, evolved in Egypt and Mesopotamia as a variant of the palmette.

Similarly, from the early 13th century to 1806 the divine right of the Holy Roman Emperors was conferred by investiture in the Imperial Regalia, which included the coronation mantle displaying the twin lions (recalling the twin lions of Aker above) guarding the palm in the form of a tree of life, with its two pendant clusters of fruit.

It is believed that the Irminsul, the sacred pillar of the Saxons and equivalent of the Norse Yggdrasil, another version of the world tree, took on its palmette form under Gallo-Roman influence.[33]

Even everyday garden gates throughout Western suburbia are topped with almost identical pairs of scrolls seemingly derived from the motifs associated with the akhet and the palmette, including the related winged sun and sun disk flanked with a pair of eyes.[3] Churchyard gates, tombs[34] and gravestones bear the motif over and again in different forms.

The anthemion is also the mint mark of the Mint of Greece, and it shows in all Greek euro coins destined for circulation, as well as in all Greek collectors' coins.

Notes

- "Silver jewelry, judaica and Christian gifts – Sterling Silver Jerusalem Hamsa". Caspi SIlver. Archived from the original on 29 February 2008. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- http://www.pollackphoto.com/nepal/kathmandu/large/F0227-10.jpg

- "Funerary Stela". 150.si.edu. Archived from the original on 10 April 2009. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- E.H. Gombrich, The Sense Of Order, A study in the psychology of decorative art, PHAIDON second edition, London 1984 page 181

- "Page Redirecting". Etc.usf.edu. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- http://www.asia.si.edu/collections/singleObject.cfm?ObjectId=3660

- "Miho Museum". Miho.or.jp. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- Archived 6 November 2003 at the Wayback Machine

- http://www.arthistory.upenn.edu/smr04/101910/Slide4.jpg

- The Art of Ancient Egypt | Publications for Educators | Explore & Learn | The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archived 2 April 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- "FORGOTTEN EMPIRE the world of Ancient Persia | 118". Thebritishmuseum.ac.uk. 23 May 2011. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- The New Greek Galleries | Explore & Learn | The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archived 11 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- "Water Jar (Getty Museum)". Getty.edu. 7 May 2009. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- https://images.google.com/images?q=anthemion&hl=en&btnG=Search+Images

- https://images.google.com/images?svnum=10&hl=en&lr=&q=Palmette&btnG=Search

- BOARDMAN, JOHN (19 April 1998). "Reflections on the Origins of Indian Stone Architecture". Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 12: 13–22. JSTOR 24049089.

- "Reflections on The origins of Indian Stone Architecture", John Boardman, p.16

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 93.

- "Stone door sill". Betnahrain.org. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- "Egyptianizing figures on either side of a tree with a winged disk [Mesopotamia, Nimrud (ancient Kalhu)] | Work of Art | Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum o". Metmuseum.org. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- Archived 20 December 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- "King on either side of a sacred Tree". Betnahrain.org. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- "Overview". Cinema Treasures. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- "wroughtironproductions.com". wroughtironproductions.com. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- Archived 27 March 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- "Oriental Rugs, Salor Images". TurkoTek. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- "Banque d'images". Imagomag. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- "Later Tibetan Gallery – Garuda". Artsofasia.biz. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- "Vajra". Keithdowman.net. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- https://images.google.com/images?svnum=10&hl=en&lr=&q=chinese+bat&btnG=Search

- http://www.shakris.com/images/W/WC103C.gif

- "CHINA: THE THREE EMPERORS, 1662–1795: Scholar Collectors". Threeemperors.org.uk. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- Simek, Rudolf (2007). Dictionary of Northern Mythology. Translated by Angela Hall. D.S. Brewer. ISBN 0-85991-513-1.

- Highgate Cemetery West : London Cemeteries Archived 29 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Palmettes. |

- Jessica Rawson, Chinese Ornament: The Lotus and the Dragon; ISBN 0-7141-1431-6, British Museum Pubns Ltd, 1984

- Alois Riegl, Stilfragen. Grundlegungen zu einer Geschichte der Ornamentik. Berlin 1893

- Helene J. Kantor, Plant Ornament in the Ancient Near East, Revised: 11 August 1999, Copyright 1999 Oriental Institute, University of Chicago

- Idris Parry, Speak Silence, ISBN 0-85635-790-1, Carcanet Press Ltd., 1988

- Gombrich, Symbolic Images: Studies in the Art of the Renaissance, London, Phaidon, 1972

- Ernst H. Gombrich, The Sense of Order, A Study in the Psychology of Decorative Art, Phaidon, 1985