Blade (archaeology)

In archaeology, a blade is a type of stone tool created by striking a long narrow flake from a stone core. This process of reducing the stone and producing the blades is called lithic reduction. Archaeologists use this process of flintknapping to analyze blades and observe their technological uses for historical peoples.

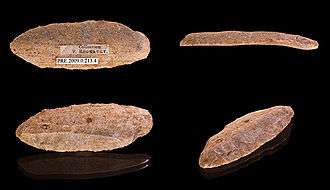

Blades are defined as being flakes that are at least twice as long as they are wide and that have parallel or subparallel sides and at least two ridges on the dorsal (outer) side. Blade cores appear and are different from regular flaking cores, as each core's conchoidal nature is suited for different types of flaking. Blades are created using stones that have a cryptocrystalline structure and easily be fractured into a smooth piece without fracturing. Blades became the favored technology of the Upper Palaeolithic era, although they are occasionally found in earlier periods. Different techniques are also required for blade creation; a soft punch or hammerstone is necessary for creating a blade.

The long sharp edges of blades made them useful for a variety of purposes. After blades are flaked, they are often incorporated as parts of larger tools, such as spears. Other times, the simple shape and sharpness serves the designed role. Blades were often employed in the impression process of material culture, assisting ancient humans in imprinting ornate designs into other parts of their material culture. Scrapers, used for hide working or woodworking, or burins, used for engraving, are two common such examples.

Cores from which blades have been struck are called blade cores and the tools created from single blades are called blade tools. Small examples (under 12 mm) are called microblades and were used in the Mesolithic as elements of composite tools. Blades with one edge blunted by removal of tiny flakes are called backed blade. A blade core becomes an exhausted core when there are no more useful angles to knock off blades.

Blades can be classified into many different types depending on their shape and size. Archaeologists have also been known to use the microscopic striations created from the lithic reduction process to classify the blades into specific types. Once classified archaeologists can use this information to see how the blade was produced, who produced it, and how it was used.

Cultural implications

Blade technology, too, is able to provide researchers with understanding of the social realms of the culture in question.[1] For example, in 2002 an article was published concerning research done in Tehran, Iran. The research focused on six late prehistoric sites which coincidentally had a large focus of blade production.[2] The main focus of the paper concentrated on the early Chalcolithic and showed that as time passed and the chopper tools became more prominent, stone tools became less aesthetically pleasing. Thus, there was a collapse of lithic craft specialization. Wherein raw material was being sent out and coming back in as blades, people were producing their own blades at home.[2] The raw materials that these tools were made of were also very diverse. 92% of the Chalcolithic tool variety was a product of chert, a sedimentary rock indigenous to the area and easily harvested. Other raw materials found in the collection, such as obsidian, suggested that trading and expeditions were sources for blade cores, too, as these raw materials were not readily available.[2] The provenance of parts of a culture's material culture illuminates common trade patterns and needs of that society for archaeologists. If the resources are not available how they traded these raw materials such as obsidian to improve their blades and stone tool technology.

Likewise, the blades and blade cores located in the Ambergris Caye Museum dated to Mayan inhabitation showed heavy reliance on obsidian. Because obsidian is not natural to Belize, the site of excavation, the obsidian cores were the product of transactions between the Mayans and those in present-day Honduras, Mexico and Guatemala. Obsidian blades are the sharpest natural cutting edges known, and after the lithic reduction already fractured blades, the triangular heads were produced. These obsidian blades were used as the Mayans' primary cutting utensil.[3]

See also

Further reading

- Butler, C (2005). Prehistoric Flintwork, Tempus, Stroud. ISBN 0-7524-3340-7.

- Darvill, T (ed.) (2003). Oxford Concise Dictionary of Archaeology, Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280005-1.

References

- Driscoll, Killian; García-Rojas, Maite (2014). "Their lips are sealed: identifying hard stone, soft stone, and antler hammer direct percussion in Palaeolithic prismatic blade production" (PDF). Journal of Archaeological Science. 47: 134–141. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2014.04.008. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- Fazeli, H.; Donahue, R.E; Coningham, R.A.E (2002). "Stone Tool Production, Distribution and use during the Late Neolithic and Chalcolithic on the Tehran Plain, Iran". Iran. 40: 1–14. doi:10.2307/4300616. JSTOR 4300616.

- Smith, Herman. "Blades and cores of Obsidian". Dig It. Retrieved 10 March 2016.