Borobudur

Borobudur, or Barabudur (Indonesian: Candi Borobudur, Javanese: ꦕꦤ꧀ꦣꦶꦧꦫꦧꦸꦣꦸꦂ, romanized: Candhi Barabudhur) is a 9th-century Mahayana Buddhist temple in Magelang Regency, not far from the town of Muntilan, in Central Java, Indonesia. It is the world's largest Buddhist temple.[1][2][3] The temple consists of nine stacked platforms, six square and three circular, topped by a central dome. It is decorated with 2,672 relief panels and 504 Buddha statues. The central dome is surrounded by 72 Buddha statues, each seated inside a perforated stupa.[4]

| Borobudur | |

|---|---|

| Native name Javanese: ꦧꦫꦧꦸꦝꦸꦂ | |

Borobudur, a UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| Location | Magelang, Central Java |

| Coordinates | 7.608°S 110.204°E |

| Built | Originally built in the 9th century during the reign of the Sailendra Dynasty |

| Restored | 1911 |

| Restored by | Theodoor van Erp |

| Architect | Gunadharma |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, vi |

| Designated | 1991 (15th session) |

| Part of | Borobudur Temple Compounds |

| Reference no. | 592 |

| State Party | |

| Region | Southeast Asia |

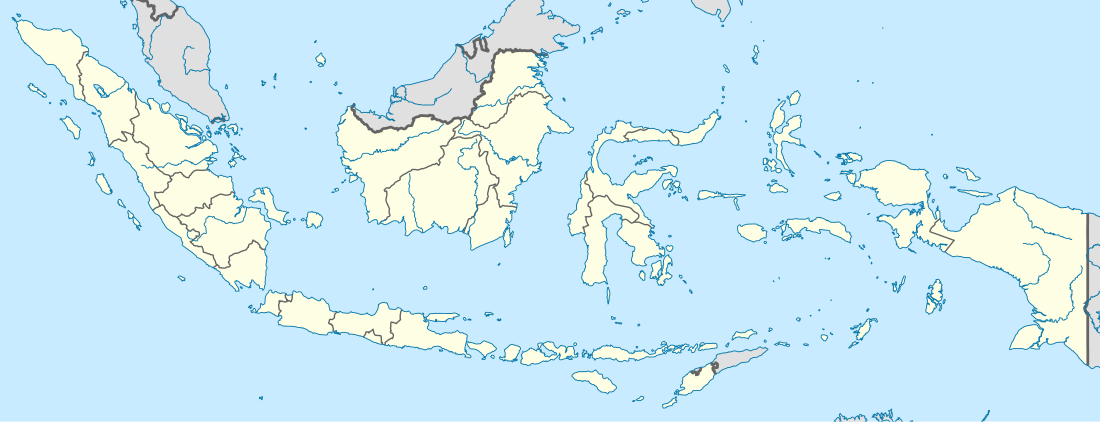

Location within Java  Borobudur (Indonesia) | |

Built in the 9th century during the reign of the Sailendra Dynasty, the temple design follows Javanese Buddhist architecture, which blends the Indonesian indigenous cult of ancestor worship and the Buddhist concept of attaining Nirvana.[3] The temple demonstrates the influences of Gupta art that reflects India's influence on the region, yet there are enough indigenous scenes and elements incorporated to make Borobudur uniquely Indonesian.[5][6] The monument is a shrine to the Lord Buddha and a place for Buddhist pilgrimage. The pilgrim journey begins at the base of the monument and follows a path around the monument, ascending to the top through three levels symbolic of Buddhist cosmology: Kāmadhātu (the world of desire), Rūpadhātu (the world of forms) and Arūpadhātu (the world of formlessness). The monument guides pilgrims through an extensive system of stairways and corridors with 1,460 narrative relief panels on the walls and the balustrades. Borobudur has one of the largest and most complete ensembles of Buddhist reliefs in the world.[3]

Evidence suggests that Borobudur was constructed in the 9th century and subsequently abandoned following the 14th-century decline of Hindu kingdoms in Java and the Javanese conversion to Islam.[7] Worldwide knowledge of its existence was sparked in 1814 by Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, then the British ruler of Java, who was advised of its location by native Indonesians.[8] Borobudur has since been preserved through several restorations. The largest restoration project was undertaken between 1975 and 1982 by the Indonesian government and UNESCO, followed by the monument's listing as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[3]

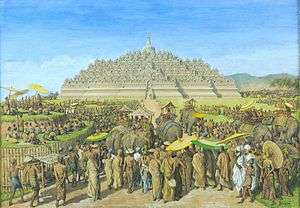

Borobudur is the largest Buddhist temple in the world, and ranks with Bagan in Myanmar and Angkor Wat in Cambodia as one of the great archeological sites of Southeast Asia. Borobudur remains popular for pilgrimage, with Buddhists in Indonesia celebrating Vesak Day at the monument. Borobudur is Indonesia's single most visited tourist attraction.[9][10][11]

Etymology

In Indonesian, ancient temples are referred to as candi; thus locals refer to "Borobudur Temple" as Candi Borobudur. The term candi also loosely describes ancient structures, for example gates and baths. The origins of the name Borobudur, however, are unclear,[12] although the original names of most ancient Indonesian temples are no longer known.[12] The name Borobudur was first written in Raffles's book on Javan history.[13] Raffles wrote about a monument called Borobudur, but there are no older documents suggesting the same name.[12] The only old Javanese manuscript that hints the monument called Budur as a holy Buddhist sanctuary is Nagarakretagama, written by Mpu Prapanca, a Buddhist scholar of Majapahit court, in 1365.[14]

Most candi are named after a nearby village. If it followed Javanese language conventions and was named after the nearby village of Bore, the monument should have been named "BudurBoro". Raffles thought that Budur might correspond to the modern Javanese word Buda ("ancient")—i.e., "ancient Boro". He also suggested that the name might derive from boro, meaning "great" or "honourable" and Budur for Buddha.[12] However, another archaeologist suggests the second component of the name (Budur) comes from Javanese term bhudhara ("mountain").[15]

Another possible etymology by Dutch archaeologist A.J. Bernet Kempers suggests that Borobudur is a corrupted simplified local Javanese pronunciation of Biara Beduhur written in Sanskrit as Vihara Buddha Uhr. The term Buddha-Uhr could mean "the city of Buddhas", while another possible term Beduhur is probably an Old Javanese term, still survived today in Balinese vocabulary, which means "a high place", constructed from the stem word dhuhur or luhur (high). This suggests that Borobudur means vihara of Buddha located on a high place or on a hill.[16]

The construction and inauguration of a sacred Buddhist building—possibly a reference to Borobudur—was mentioned in two inscriptions, both discovered in Kedu, Temanggung Regency. The Karangtengah inscription, dated 824, mentioned a sacred building named Jinalaya (the realm of those who have conquered worldly desire and reached enlightenment), inaugurated by Pramodhawardhani, daughter of Samaratungga. The Tri Tepusan inscription, dated 842, is mentioned in the sima, the (tax-free) lands awarded by Çrī Kahulunnan (Pramodhawardhani) to ensure the funding and maintenance of a Kamūlān called Bhūmisambhāra.[17] Kamūlān is from the word mula, which means "the place of origin", a sacred building to honor the ancestors, probably those of the Sailendras. Casparis suggested that Bhūmi Sambhāra Bhudhāra, which in Sanskrit means "the mountain of combined virtues of the ten stages of Boddhisattvahood", was the original name of Borobudur.[18]

Location

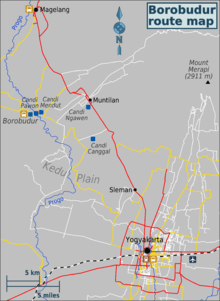

The three temples

Approximately 40 kilometres (25 mi) northwest of Yogyakarta and 86 kilometres (53 mi) west of Surakarta, Borobudur is located in an elevated area between two twin volcanoes, Sundoro-Sumbing and Merbabu-Merapi, and two rivers, the Progo and the Elo. According to local myth, the area known as Kedu Plain is a Javanese "sacred" place and has been dubbed "the garden of Java" due to its high agricultural fertility.[19]

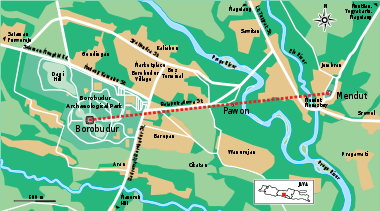

During the restoration in the early 20th century, it was discovered that three Buddhist temples in the region, Borobudur, Pawon and Mendut, are positioned along a straight line.[20] A ritual relationship between the three temples must have existed, although the exact ritual process is unknown.[14]

Ancient lake hypothesis

Speculation about a surrounding lake's existence was the subject of intense discussion among archaeologists in the 20th century. In 1931, a Dutch artist and scholar of Hindu and Buddhist architecture, W.O.J. Nieuwenkamp, developed a hypothesis that the Kedu Plain was once a lake and Borobudur initially represented a lotus flower floating on the lake.[15] It has been claimed that Borobudur was built on a bedrock hill, 265 m (869 ft) above sea level and 15 m (49 ft) above the floor of a dried-out paleolake.[21]

Dumarçay together with Professor Thanikaimoni took soil samples in 1974 and again in 1977 from trial trenches that had been dug into the hill, as well as from the plain immediately to the south. These samples were later analysed by Thanikaimoni, who examined their pollen and spore content to identify the type of vegetation that had grown in the area around the time of Borobudur's construction. They were unable to discover any pollen or spore samples that were characteristic of any vegetation known to grow in an aquatic environment such as a lake, pond or marsh. The area surrounding Borobudur appears to have been surrounded by agricultural land and palm trees at the time of the monument's construction, as is still the case today. Caesar Voûte and the geomorphologist Dr J.J. Nossin in 1985–86 field studies re-examined the Borobudur lake hypothesis and confirmed the absence of a lake around Borobudur at the time of its construction and active use as a sanctuary. These findings A New Perspective on Some Old Questions Pertaining to Borobudur were published in the 2005 UNESCO publication titled "The Restoration of Borobudur".

History

Construction

There are no known records of construction or the intended purpose of Borobudur.[22] The duration of construction has been estimated by comparison of carved reliefs on the temple's hidden foot and the inscriptions commonly used in royal charters during the 8th and 9th centuries. Borobudur was likely founded around 800 AD.[22] This corresponds to the period between 760 and 830 AD, the peak of the Sailendra dynasty rule over Mataram kingdom in central Java,[23] when their power encompassed not only the Srivijayan Empire but also southern Thailand, Indianized kingdoms of Philippines, North Malaya (Kedah, also known in Indian texts as the ancient Hindu state of Kadaram).[24][25][26] The construction has been estimated to have taken 75 years with completion during the reign of Samaratungga in 825.[27][28]

There is uncertainty about Hindu and Buddhist rulers in Java around that time. The Sailendras were known as ardent followers of Buddhism, though stone inscriptions found at Sojomerto also suggest they may have been Hindus.[27] It was during this time that many Hindu and Buddhist monuments were built on the plains and mountains around the Kedu Plain. The Buddhist monuments, including Borobudur, were erected around the same period as the Hindu Shiva Prambanan temple compound. In 732 AD, the Shivaite King Sanjaya commissioned a Shivalinga sanctuary to be built on the Wukir hill, only 10 km (6.2 mi) east of Borobudur.[29]

Construction of Buddhist temples, including Borobudur, at that time was possible because Sanjaya's immediate successor, Rakai Panangkaran, granted his permission to the Buddhist followers to build such temples.[30] In fact, to show his respect, Panangkaran gave the village of Kalasan to the Buddhist community, as is written in the Kalasan Charter dated 778 AD.[30] This has led some archaeologists to believe that there was never serious conflict concerning religion in Java as it was possible for a Hindu king to patronize the establishment of a Buddhist monument; or for a Buddhist king to act likewise.[31] However, it is likely that there were two rival royal dynasties in Java at the time—the Buddhist Sailendra and the Saivite Sanjaya—in which the latter triumphed over their rival in the 856 battle on the Ratubaka plateau.[32] Similar confusion also exists regarding the Lara Jonggrang temple at the Prambanan complex, which was believed to have been erected by the victor Rakai Pikatan as the Sanjaya dynasty's reply to Borobudur,[32] but others suggest that there was a climate of peaceful coexistence where Sailendra involvement exists in Lara Jonggrang.[33]

Abandonment

Borobudur lay hidden for centuries under layers of volcanic ash and jungle growth. The facts behind its abandonment remain a mystery. It is not known when active use of the monument and Buddhist pilgrimage to it ceased. Sometime between 928 and 1006, King Mpu Sindok moved the capital of the Medang Kingdom to the region of East Java after a series of volcanic eruptions; it is not certain whether this influenced the abandonment, but several sources mention this as the most likely period of abandonment.[7][21] The monument is mentioned vaguely as late as c. 1365, in Mpu Prapanca's Nagarakretagama, written during the Majapahit era and mentioning "the vihara in Budur".[34] Soekmono (1976) also mentions the popular belief that the temples were disbanded when the population converted to Islam in the 15th century.[7]

The monument was not forgotten completely, though folk stories gradually shifted from its past glory into more superstitious beliefs associated with bad luck and misery. Two old Javanese chronicles (babad) from the 18th century mention cases of bad luck associated with the monument. According to the Babad Tanah Jawi (or the History of Java), the monument was a fatal factor for Mas Dana, a rebel who revolted against Pakubuwono I, the king of Mataram in 1709.[7] It was mentioned that the "Redi Borobudur" hill was besieged and the insurgents were defeated and sentenced to death by the king. In the Babad Mataram (or the History of the Mataram Kingdom), the monument was associated with the misfortune of Prince Monconagoro, the crown prince of the Yogyakarta Sultanate in 1757.[35] In spite of a taboo against visiting the monument, "he took what is written as the knight who was captured in a cage (a statue in one of the perforated stupas)". Upon returning to his palace, he fell ill and died one day later.

Rediscovery

Following its capture, Java was under British administration from 1811 to 1816. The appointed governor was Lieutenant Governor-General Thomas Stamford Raffles, who took great interest in the history of Java. He collected Javanese antiques and made notes through contacts with local inhabitants during his tour throughout the island. On an inspection tour to Semarang in 1814, he was informed about a big monument deep in a jungle near the village of Bumisegoro.[35] He was not able to see the site himself, but sent Hermann Cornelius, a Dutch engineer who, among other antiquity explorations had uncovered the Sewu complex in 1806–07, to investigate. In two months, Cornelius and his 200 men cut down trees, burned down vegetation and dug away the earth to reveal the monument. Due to the danger of collapse, he could not unearth all galleries. He reported his findings to Raffles, including various drawings. Although Raffles mentioned the discovery and hard work by Cornelius and his men in only a few sentences, he has been credited with the monument's rediscovery, as the one who had brought it to the world's attention.[13]

Christiaan Lodewijk Hartmann, the Resident of the Kedu region, continued Cornelius's work, and in 1835, the whole complex was finally unearthed. His interest in Borobudur was more personal than official. Hartmann did not write any reports of his activities, in particular, the alleged story that he discovered the large statue of Buddha in the main stupa.[36] In 1842, Hartmann investigated the main dome, although what he discovered is unknown and the main stupa remains empty.

The Dutch East Indies government then commissioned Frans Carel Wilsen, a Dutch engineering official, who studied the monument and drew hundreds of relief sketches. Jan Frederik Gerrit Brumund was also appointed to make a detailed study of the monument, which was completed in 1859. The government intended to publish an article based on Brumund's study supplemented by Wilsen's drawings, but Brumund refused to cooperate. The government then commissioned another scholar, Conradus Leemans, who compiled a monograph based on Brumund's and Wilsen's sources. In 1873, the first monograph of the detailed study of Borobudur was published, followed by its French translation a year later.[36] The first photograph of the monument was taken in 1872 by the Dutch-Flemish engraver Isidore van Kinsbergen.[37]

Appreciation of the site developed slowly, and it served for some time largely as a source of souvenirs and income for "souvenir hunters" and thieves. In 1882, the chief inspector of cultural artifacts recommended that Borobudur be entirely disassembled with the relocation of reliefs into museums due to the unstable condition of the monument.[37] As a result, the government appointed Willem Pieter Groeneveldt, curator of the archaeological collection of the Batavian Society of Arts and Sciences,[38] to undertake a thorough investigation of the site and to assess the actual condition of the complex; his report found that these fears were unjustified and recommended it be left intact.

Borobudur was considered as the source of souvenirs, and parts of its sculptures were looted, some even with colonial-government consent. In 1896 King Chulalongkorn of Siam visited Java and requested and was allowed to take home eight cartloads of sculptures taken from Borobudur. These include thirty pieces taken from a number of relief panels, five buddha images, two lions, one gargoyle, several kala motifs from the stairs and gateways, and a guardian statue (dvarapala). Several of these artifacts, most notably the lions, dvarapala, kala, makara and giant waterspouts are now on display in the Java Art room in The National Museum in Bangkok.[39]

Restoration

Borobudur attracted attention in 1885, when the Dutch engineer Jan Willem IJzerman, Chairman of the Archaeological Society in Yogyakarta, made a discovery about the hidden foot.[40] Photographs that reveal reliefs on the hidden foot were made in 1890–1891.[41] The discovery led the Dutch East Indies government to take steps to safeguard the monument. In 1900, the government set up a commission consisting of three officials to assess the monument: Jan Lourens Andries Brandes, an art historian, Theodoor van Erp, a Dutch army engineer officer, and Benjamin Willem van de Kamer, a construction engineer from the Department of Public Works.

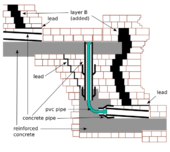

In 1902, the commission submitted a threefold plan of proposal to the government. First, the immediate dangers should be avoided by resetting the corners, removing stones that endangered the adjacent parts, strengthening the first balustrades and restoring several niches, archways, stupas and the main dome. Second, after fencing off the courtyards, proper maintenance should be provided and drainage should be improved by restoring floors and spouts. Third, all loose stones should be removed, the monument cleared up to the first balustrades, disfigured stones removed and the main dome restored. The total cost was estimated at that time around 48,800 Dutch guilders.

The restoration then was carried out between 1907 and 1911, using the principles of anastylosis and led by Theodor van Erp.[42] The first seven months of restoration were occupied with excavating the grounds around the monument to find missing Buddha heads and panel stones. Van Erp dismantled and rebuilt the upper three circular platforms and stupas. Along the way, Van Erp discovered more things he could do to improve the monument; he submitted another proposal, which was approved with the additional cost of 34,600 guilders. At first glance, Borobudur had been restored to its old glory. Van Erp went further by carefully reconstructing the chattra (three-tiered parasol) pinnacle on top of the main stupa. However, he later dismantled the chattra, citing that there were not enough original stones used in reconstructing the pinnacle, which means that the original design of Borobudur's pinnacle is actually unknown. The dismantled chattra now is stored in Karmawibhangga Museum, a few hundred meters north from Borobudur.

Due to the limited budget, the restoration had been primarily focused on cleaning the sculptures, and Van Erp did not solve the drainage problem. Within fifteen years, the gallery walls were sagging, and the reliefs showed signs of new cracks and deterioration.[42] Van Erp used concrete from which alkali salts and calcium hydroxide leached and were transported into the rest of the construction. This caused some problems, so that a further thorough renovation was urgently needed.

Small restorations had been performed since then, but not sufficient for complete protection. During World War II and Indonesian National Revolution in 1945 to 1949, Borobudur restoration efforts were halted. The monument suffered further from the weather and drainage problems, which caused the earth core inside the temple to expand, pushing the stone structure and tilting the walls. By 1950s some parts of Borobudur were facing imminent danger of collapsing. In 1965, Indonesia asked the UNESCO for advice on ways to counteract the problem of weathering at Borobudur and other monuments. In 1968 Professor Soekmono, then head of the Archeological Service of Indonesia, launched his "Save Borobudur" campaign, in an effort to organize a massive restoration project.[43]

.jpg)

In the late 1960s, the Indonesian government had requested from the international community a major renovation to protect the monument. In 1973, a master plan to restore Borobudur was created.[44] Through an Agreement concerning the Voluntary Contributions to be Given for the Execution of the Project to Preserve Borobudur (Paris, 29 January 1973), 5 countries agreed to contribute to the restoration: Australia (AUD $200,000), Belgium (BEF fr.250,000), Cyprus (CYP £100,000), France (USD $77,500) and Germany (DEM DM 2,000,000).[45] The Indonesian government and UNESCO then undertook the complete overhaul of the monument in a big restoration project between 1975 and 1982.[42] In 1975, the actual work began. Over one million stones were dismantled and removed during the restoration, and set aside like pieces of a massive jig-saw puzzle to be individually identified, catalogued, cleaned and treated for preservation. Borobudur became a testing ground for new conservation techniques, including new procedures to battle the microorganisms attacking the stone.[43] The foundation was stabilized, and all 1,460 panels were cleaned. The restoration involved the dismantling of the five square platforms and the improvement of drainage by embedding water channels into the monument. Both impermeable and filter layers were added. This colossal project involved around 600 people to restore the monument and cost a total of US$6,901,243.[46]

After the renovation was finished, UNESCO listed Borobudur as a World Heritage Site in 1991.[3] It is listed under Cultural criteria (i) "to represent a masterpiece of human creative genius", (ii) "to exhibit an important interchange of human values, over a span of time or within a cultural area of the world, on developments in architecture or technology, monumental arts, town-planning or landscape design", and (vi) "to be directly or tangibly associated with events or living traditions, with ideas, or with beliefs, with artistic and literary works of outstanding universal significance".[3]

In December 2017, the idea to reinstall chattra on top of Borobudur main stupa's yasthi has been revisited. However, expert said a thorough study is needed on restoring the umbrella-shaped pinnacle. By early 2018, the chattra restoration has not yet commenced.[47]

Contemporary events

Religious ceremony

Following the major 1973 renovation funded by UNESCO,[44] Borobudur is once again used as a place of worship and pilgrimage. Once a year, during the full moon in May or June, Buddhists in Indonesia observe Vesak (Indonesian: Waisak) day commemorating the birth, death, and the time when Siddhārtha Gautama attained the highest wisdom to become the Buddha Shakyamuni. Vesak is an official national holiday in Indonesia,[48] and the ceremony is centered at the three Buddhist temples by walking from Mendut to Pawon and ending at Borobudur.[49]

Tourism

The monument is the single most visited tourist attraction in Indonesia. In 1974, 260,000 tourists, of whom 36,000 were foreigners, visited the monument.[10] The figure climbed to 2.5 million visitors annually (80% were domestic tourists) in the mid-1990s, before the country's economic crisis.[11] Tourism development, however, has been criticized for not including the local community, giving rise to occasional conflicts.[10] In 2003, residents and small businesses around Borobudur organized several meetings and poetry protests, objecting to a provincial government plan to build a three-storey mall complex, dubbed the "Java World".[50]

International tourism awards were given to Borobudur archaeological park, such as PATA Grand Pacific Award 2004, PATA Gold Award Winner 2011, and PATA Gold Award Winner 2012. In June 2012, Borobudur was recorded in the Guinness Book of World Records as the world's largest Buddhist archaeological site.[51]

Conservation

UNESCO identified three specific areas of concern under the present state of conservation: (i) vandalism by visitors; (ii) soil erosion in the south-eastern part of the site; and (iii) analysis and restoration of missing elements.[52] The soft soil, the numerous earthquakes and heavy rains lead to the destabilization of the structure. Earthquakes are by far the most important contributing factors, since not only do stones fall down and arches crumble, but the earth itself can move in waves, further destroying the structure.[52] The increasing popularity of the stupa brings in many visitors, most of whom are from Indonesia. Despite warning signs on all levels not to touch anything, the regular transmission of warnings over loudspeakers and the presence of guards, vandalism on reliefs and statues is a common occurrence and problem, leading to further deterioration. As of 2009, there is no system in place to limit the number of visitors allowed per day or to introduce mandatory guided tours only.[52]

In August 2014, the Conservation Authority of Borobudur reported some severe abrasion of the stone stairs caused by the scraping of visitors' footwear. The conservation authority planned to install wooden stairs to cover and protect the original stone stairs, just like those installed in Angkor Wat.[53]

Rehabilitation

Borobudur was heavily affected by the eruption of Mount Merapi in October and November 2010. Volcanic ash from Merapi fell on the temple complex, which is approximately 28 kilometres (17 mi) west-southwest of the crater. A layer of ash up to 2.5 centimetres (1 in)[54] thick fell on the temple statues during the eruption of 3–5 November, also killing nearby vegetation, with experts fearing that the acidic ash might damage the historic site. The temple complex was closed from 5 to 9 November to clean up the ashfall.[55][56]

UNESCO donated US$3 million as a part of the costs towards the rehabilitation of Borobudur after Mount Merapi's 2010 eruption.[57] More than 55,000 stone blocks comprising the temple's structure were dismantled to restore the drainage system, which had been clogged by slurry after the rain. The restoration was finished in November.[58]

In January 2012, two German stone-conservation experts spent ten days at the site analyzing the temples and making recommendations to ensure their long-term preservation.[59] In June, Germany agreed to contribute $130,000 to UNESCO for the second phase of rehabilitation, in which six experts in stone conservation, microbiology, structural engineering and chemical engineering would spend a week in Borobudur in June, then return for another visit in September or October. These missions would launch the preservation activities recommended in the January report and would include capacity building activities to enhance the preservation capabilities of governmental staff and young conservation experts.[60]

On 14 February 2014, major tourist attractions in Yogyakarta and Central Java, including Borobudur, Prambanan and Ratu Boko, were closed to visitors, after being severely affected by the volcanic ash from the eruption of Kelud volcano in East Java, located around 200 kilometers east from Yogyakarta. Workers covered the iconic stupas and statues of Borobudur temple to protect the structure from volcanic ash. The Kelud volcano erupted on 13 February 2014 with an explosion heard as far away as Yogyakarta.[61]

Security threats

On 21 January 1985, nine stupas were badly damaged by nine bombs.[62][63] In 1991, a blind Muslim preacher, Husein Ali Al Habsyie, was sentenced to life imprisonment for masterminding a series of bombings in the mid-1980s, including the temple attack.[64] Two other members of the Islamic extremist group that carried out the bombings were each sentenced to 20 years in 1986, and another man received a 13-year prison term.

On 27 May 2006, an earthquake of 6.2 magnitude struck the south coast of Central Java. The event caused severe damage around the region and casualties to the nearby city of Yogyakarta, but Borobudur remained intact.[65]

In August 2014, Indonesian police and security forces tightened the security in and around Borobudur temple compound, as a precaution to a threat posted on social media by a self-proclaimed Indonesian branch of ISIS, citing that the terrorists planned to destroy Borobudur and other statues in Indonesia.[66] The security improvements included the repair and increased deployment of CCTV monitors and the implementation of a night patrol in and around the temple compound. The jihadist group follows a strict interpretation of Islam that condemns any anthropomorphic representations such as sculptures as idolatry.

Visitor overload problem

The high volume of visitors ascending the Borobudur's narrow stairs, has caused a severe wear out on the stone of the stairs, eroding the stones surface and made them thinner and smoother. Overall, Borobudur has 2,033 surfaces of stone stairs, spread over four cardinal directions; including the west side, the east, south and north. There are around 1,028 surfaces of them, or about 49.15 percent, that are severely worn out.[67]

To avoid further wear of stairs' stones, since November 2014, two main sections of Borobudur stairs – the eastern (ascending route) and northern (descending route) sides – are covered with wooden structures. The similar technique has been applied in Angkor Wat in Cambodia and Egyptian Pyramids.[67] In March 2015, Borobudur Conservation Center proposed further to seal the stairs with rubber cover.[68] Proposals have also been made that visitors be issued special sandals.[69]

Architecture

The archaeological excavation into Borobudur during reconstruction suggests that adherents of Hinduism or a pre-Indic faith had already begun to erect a large structure on Borobudur's hill before the site was appropriated by Buddhists. The foundations are unlike any Hindu or Buddhist shrine structures, and therefore, the initial structure is considered more indigenous Javanese than Hindu or Buddhist.[70]

Design

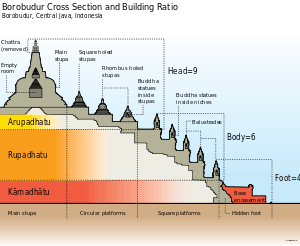

Borobudur is built as a single large stupa and, when viewed from above, takes the form of a giant tantric Buddhist mandala, simultaneously representing the Buddhist cosmology and the nature of mind.[71] The original foundation is a square, approximately 118 metres (387 ft) on each side. It has nine platforms, of which the lower six are square and the upper three are circular.[72] The upper platform features seventy-two small stupas surrounding one large central stupa. Each stupa is bell-shaped and pierced by numerous decorative openings. Statues of the Buddha sit inside the pierced enclosures.

The design of Borobudur took the form of a step pyramid. Previously, the prehistoric Austronesian megalithic culture in Indonesia had constructed several earth mounds and stone step pyramid structures called punden berundak as discovered in Pangguyangan site near Cisolok[73] and in Cipari near Kuningan.[74] The construction of stone pyramids is based on native beliefs that mountains and high places are the abode of ancestral spirits or hyangs.[75] The punden berundak step pyramid is the basic design in Borobudur,[76] believed to be the continuation of older megalithic tradition incorporated with Mahayana Buddhist ideas and symbolism.[77]

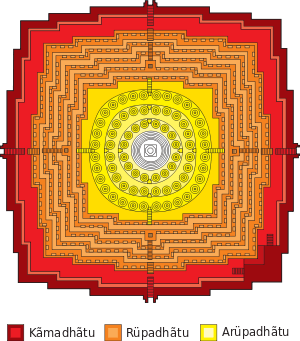

The monument's three divisions symbolize the three "realms" of Buddhist cosmology, namely Kamadhatu (the world of desires), Rupadhatu (the world of forms), and finally Arupadhatu (the formless world). Ordinary sentient beings live out their lives on the lowest level, the realm of desire. Those who have burnt out all desire for continued existence leave the world of desire and live in the world on the level of form alone: they see forms but are not drawn to them. Finally, full Buddhas go beyond even form and experience reality at its purest, most fundamental level, the formless ocean of nirvana.[78] The liberation from the cycle of Saṃsāra where the enlightened soul had no longer attached to worldly form corresponds to the concept of Śūnyatā, the complete voidness or the nonexistence of the self. Kāmadhātu is represented by the base, Rupadhatu by the five square platforms (the body), and Arupadhatu by the three circular platforms and the large topmost stupa. The architectural features between the three stages have metaphorical differences. For instance, square and detailed decorations in the Rupadhatu disappear into plain circular platforms in the Arupadhatu to represent how the world of forms—where men are still attached with forms and names—changes into the world of the formless.[79]

Congregational worship in Borobudur is performed in a walking pilgrimage. Pilgrims are guided by the system of staircases and corridors ascending to the top platform. Each platform represents one stage of enlightenment. The path that guides pilgrims was designed to symbolize Buddhist cosmology.[80]

In 1885, a hidden structure under the base was accidentally discovered.[40] The "hidden footing" contains reliefs, 160 of which are narratives describing the real Kāmadhātu. The remaining reliefs are panels with short inscriptions that apparently provide instructions for the sculptors, illustrating the scenes to be carved.[81] The real base is hidden by an encasement base, the purpose of which remains a mystery. It was first thought that the real base had to be covered to prevent a disastrous subsidence of the monument into the hill.[81] There is another theory that the encasement base was added because the original hidden footing was incorrectly designed, according to Vastu Shastra, the Indian ancient book about architecture and town planning.[40] Regardless of why it was commissioned, the encasement base was built with detailed and meticulous design and with aesthetic and religious consideration.

Building structure

Approximately 55,000 cubic metres (72,000 cu yd) of andesite stones were taken from neighbouring stone quarries to build the monument.[82] The stone was cut to size, transported to the site and laid without mortar. Knobs, indentations and dovetails were used to form joints between stones. The roof of stupas, niches and arched gateways were constructed in corbelling method. Reliefs were created in situ after the building had been completed.

The monument is equipped with a good drainage system to cater to the area's high stormwater run-off. To prevent flooding, 100 spouts are installed at each corner, each with a unique carved gargoyle in the shape of a giant or makara.

Borobudur differs markedly from the general design of other structures built for this purpose. Instead of being built on a flat surface, Borobudur is built on a natural hill. However, construction technique is similar to other temples in Java. Without the inner spaces seen in other temples, and with a general design similar to the shape of pyramid, Borobudur was first thought more likely to have served as a stupa, instead of a temple.[82] A stupa is intended as a shrine for the Buddha. Sometimes stupas were built only as devotional symbols of Buddhism. A temple, on the other hand, is used as a house of worship. The meticulous complexity of the monument's design suggests that Borobudur is in fact a temple.

Little is known about Gunadharma, the architect of the complex.[83] His name is recounted from Javanese folk tales rather than from written inscriptions.

The basic unit of measurement used during construction was the tala, defined as the length of a human face from the forehead's hairline to the tip of the chin or the distance from the tip of the thumb to the tip of the middle finger when both fingers are stretched at their maximum distance.[84] The unit is thus relative from one individual to the next, but the monument has exact measurements. A survey conducted in 1977 revealed frequent findings of a ratio of 4:6:9 around the monument. The architect had used the formula to lay out the precise dimensions of the fractal and self-similar geometry in Borobudur's design.[84][85] This ratio is also found in the designs of Pawon and Mendut, nearby Buddhist temples. Archeologists have conjectured that the 4:6:9 ratio and the tala have calendrical, astronomical and cosmological significance, as is the case with the temple of Angkor Wat in Cambodia.[83]

The main structure can be divided into three components: base, body, and top.[83] The base is 123 m × 123 m (404 ft × 404 ft) in size with 4 metres (13 ft) walls.[82] The body is composed of five square platforms, each of diminishing height. The first terrace is set back 7 metres (23 ft) from the edge of the base. Each subsequent terrace is set back 2 metres (6.6 ft), leaving a narrow corridor at each stage. The top consists of three circular platforms, with each stage supporting a row of perforated stupas, arranged in concentric circles. There is one main dome at the center, the top of which is the highest point of the monument, 35 metres (115 ft) above ground level. Stairways at the center of each of the four sides give access to the top, with a number of arched gates overlooked by 32 lion statues. The gates are adorned with Kala's head carved on top of each and Makaras projecting from each side. This Kala-Makara motif is commonly found on the gates of Javanese temples. The main entrance is on the eastern side, the location of the first narrative reliefs. Stairways on the slopes of the hill also link the monument to the low-lying plain.

Reliefs

Borobudur is constructed in such a way that it reveals various levels of terraces, showing intricate architecture that goes from being heavily ornamented with bas-reliefs to being plain in Arupadhatu circular terraces.[86] The first four terrace walls are showcases for bas-relief sculptures. These are exquisite, considered to be the most elegant and graceful in the ancient Buddhist world.[87]

The bas-reliefs in Borobudur depicted many scenes of daily life in 8th-century ancient Java, from the courtly palace life, hermit in the forest, to those of commoners in the village. It also depicted temple, marketplace, various flora and fauna, and also native vernacular architecture. People depicted here are the images of king, queen, princes, noblemen, courtier, soldier, servant, commoners, priest and hermit. The reliefs also depicted mythical spiritual beings in Buddhist beliefs such as asuras, gods, bodhisattvas, kinnaras, gandharvas and apsaras. The images depicted on bas-relief often served as reference for historians to research for certain subjects, such as the study of architecture, weaponry, economy, fashion, and also mode of transportation of 8th-century Maritime Southeast Asia. One of the famous renderings of an 8th-century Southeast Asian double outrigger ship is Borobudur Ship.[88] Today, the actual-size replica of Borobudur Ship that had sailed from Indonesia to Africa in 2004 is displayed in the Samudra Raksa Museum, located a few hundred meters north of Borobudur.[89]

The Borobudur reliefs also pay close attention to Indian aesthetic discipline, such as pose and gesture that contain certain meanings and aesthetic value. The reliefs of noblemen, and noble women, kings, or divine beings such as apsaras, taras and boddhisattvas are usually portrayed in tribhanga pose, the three-bend pose on neck, hips, and knee, with one leg resting and one upholding the body weight. This position is considered as the most graceful pose, such as the figure of Surasundari holding a lotus.[90]

During Borobudur excavation, archeologists discovered colour pigments of blue, red, green, black, as well as bits of gold foil, and concluded that the monument that we see today – a dark gray mass of volcanic stone, lacking in colour – was probably once coated with varjalepa white plaster and then painted with bright colors, serving perhaps as a beacon of Buddhist teaching.[91] The same vajralepa plaster can also be found in Sari, Kalasan and Sewu temples. It is likely that the bas-reliefs of Borobudur was originally quite colourful, before centuries of torrential tropical rainfalls peeled-off the colour pigments.

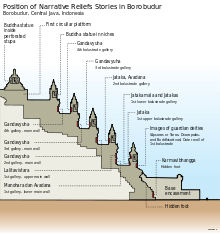

| Section | Location | Story | No. of panels |

|---|---|---|---|

| hidden foot | wall | Karmavibhangga | 160 |

| first gallery | main wall | Lalitavistara | 120 |

| Jataka/Avadana | 120 | ||

| balustrade | Jataka/Avadana | 372 | |

| Jataka/Avadana | 128 | ||

| second gallery | balustrade | Jataka/Avadana | 100 |

| main wall | Gandavyuha | 128 | |

| third gallery | main wall | Gandavyuha | 88 |

| balustrade | Gandavyuha | 88 | |

| fourth gallery | main wall | Gandavyuha | 84 |

| balustrade | Gandavyuha | 72 | |

| Total | 1,460 | ||

Borobudur contains approximately 2,670 individual bas reliefs (1,460 narrative and 1,212 decorative panels), which cover the façades and balustrades. The total relief surface is 2,500 square metres (27,000 sq ft), and they are distributed at the hidden foot (Kāmadhātu) and the five square platforms (Rupadhatu).[92]

The narrative panels, which tell the story of Sudhana and Manohara,[93] are grouped into 11 series that encircle the monument with a total length of 3,000 metres (9,800 ft). The hidden foot contains the first series with 160 narrative panels, and the remaining 10 series are distributed throughout walls and balustrades in four galleries starting from the eastern entrance stairway to the left. Narrative panels on the wall read from right to left, while those on the balustrade read from left to right. This conforms with pradaksina, the ritual of circumambulation performed by pilgrims who move in a clockwise direction while keeping the sanctuary to their right.[94]

The hidden foot depicts the workings of karmic law. The walls of the first gallery have two superimposed series of reliefs; each consists of 120 panels. The upper part depicts the biography of the Buddha, while the lower part of the wall and also the balustrades in the first and the second galleries tell the story of the Buddha's former lives.[92] The remaining panels are devoted to Sudhana's further wandering about his search, terminated by his attainment of the Perfect Wisdom.

The law of karma (Karmavibhangga)

The 160 hidden panels do not form a continuous story, but each panel provides one complete illustration of cause and effect.[92] There are depictions of blameworthy activities, from gossip to murder, with their corresponding punishments. There are also praiseworthy activities, that include charity and pilgrimage to sanctuaries, and their subsequent rewards. The pains of hell and the pleasure of heaven are also illustrated. There are scenes of daily life, complete with the full panorama of samsara (the endless cycle of birth and death). The encasement base of the Borobudur temple was disassembled to reveal the hidden foot, and the reliefs were photographed by Casijan Chepas in 1890. It is these photographs that are displayed in Borobudur Museum (Karmawibhangga Museum), located just several hundred meters north of the temple. During the restoration, the foot encasement was reinstalled, covering the Karmawibhangga reliefs. Today, only the southeast corner of the hidden foot is revealed and visible for visitors.

The story of Prince Siddhartha and the birth of Buddha (Lalitavistara)

The story starts with the descent of the Lord Buddha from the Tushita heaven and ends with his first sermon in the Deer Park near Benares.[94] The relief shows the birth of the Buddha as Prince Siddhartha, son of King Suddhodana and Queen Maya of Kapilavastu (in Nepal).

The story is preceded by 27 panels showing various preparations, in the heavens and on the earth, to welcome the final incarnation of the Bodhisattva.[94] Before descending from Tushita heaven, the Bodhisattva entrusted his crown to his successor, the future Buddha Maitreya. He descended on earth in the shape of white elephants with six tusks, penetrated to Queen Maya's right womb. Queen Maya had a dream of this event, which was interpreted that his son would become either a sovereign or a Buddha.

While Queen Maya felt that it was the time to give birth, she went to the Lumbini park outside the Kapilavastu city. She stood under a plaksa tree, holding one branch with her right hand, and she gave birth to a son, Prince Siddhartha. The story on the panels continues until the prince becomes the Buddha.

The stories of Buddha's previous life (Jataka) and other legendary people (Avadana)

Jatakas are stories about the Buddha before he was born as Prince Siddhartha.[95] They are the stories that tell about the previous lives of the Buddha, in both human and animal form. The future Buddha may appear in them as a king, an outcast, a god, an elephant—but, in whatever form, he exhibits some virtue that the tale thereby inculcates.[96] Avadanas are similar to jatakas, but the main figure is not the Bodhisattva himself. The saintly deeds in avadanas are attributed to other legendary persons. Jatakas and avadanas are treated in one and the same series in the reliefs of Borobudur.

The first twenty lower panels in the first gallery on the wall depict the Sudhanakumaravadana, or the saintly deeds of Sudhana. The first 135 upper panels in the same gallery on the balustrades are devoted to the 34 legends of the Jatakamala.[97] The remaining 237 panels depict stories from other sources, as do the lower series and panels in the second gallery. Some jatakas are depicted twice, for example the story of King Sibhi (Rama's forefather).

Sudhana's search for the ultimate truth (Gandavyuha)

Gandavyuha is the story told in the final chapter of the Avatamsaka Sutra about Sudhana's tireless wandering in search of the Highest Perfect Wisdom. It covers two galleries (third and fourth) and also half of the second gallery, comprising in total of 460 panels.[98] The principal figure of the story, the youth Sudhana, son of an extremely rich merchant, appears on the 16th panel. The preceding 15 panels form a prologue to the story of the miracles during Buddha's samadhi in the Garden of Jeta at Sravasti.

During his search, Sudhana visited no fewer than thirty teachers, but none of them had satisfied him completely. He was then instructed by Manjusri to meet the monk Megasri, where he was given the first doctrine. As his journey continues, Sudhana meets (in the following order) Supratisthita, the physician Megha (Spirit of Knowledge), the banker Muktaka, the monk Saradhvaja, the upasika Asa (Spirit of Supreme Enlightenment), Bhismottaranirghosa, the Brahmin Jayosmayatna, Princess Maitrayani, the monk Sudarsana, a boy called Indriyesvara, the upasika Prabhuta, the banker Ratnachuda, King Anala, the god Siva Mahadeva, Queen Maya, Bodhisattva Maitreya and then back to Manjusri. Each meeting has given Sudhana a specific doctrine, knowledge and wisdom. These meetings are shown in the third gallery.

After the last meeting with Manjusri, Sudhana went to the residence of Bodhisattva Samantabhadra, depicted in the fourth gallery. The entire series of the fourth gallery is devoted to the teaching of Samantabhadra. The narrative panels finally end with Sudhana's achievement of the Supreme Knowledge and the Ultimate Truth.[99]

Buddha statues

Apart from the story of the Buddhist cosmology carved in stone, Borobudur has many statues of various Buddhas. The cross-legged statues are seated in a lotus position and distributed on the five square platforms (the Rupadhatu level), as well as on the top platform (the Arupadhatu level).

The Buddha statues are in niches at the Rupadhatu level, arranged in rows on the outer sides of the balustrades, the number of statues decreasing as platforms progressively diminish to the upper level. The first balustrades have 104 niches, the second 104, the third 88, the fourth 72 and the fifth 64. In total, there are 432 Buddha statues at the Rupadhatu level.[4] At the Arupadhatu level (or the three circular platforms), Buddha statues are placed inside perforated stupas. The first circular platform has 32 stupas, the second 24 and the third 16, which adds up to 72 stupas.[4] Of the original 504 Buddha statues, over 300 are damaged (mostly headless), and 43 are missing. Since the monument's discovery, heads have been acquired as collector's items, mostly by Western museums.[100] Some of these Buddha heads are now displayed in numbers of museums, such as the Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam, Musée Guimet in Paris, and The British Museum in London.[101] Germany has in 2014 returned its collection and funded their reattachment and further conservation of the site.[102]

At first glance, all the Buddha statues appear similar, but there is a subtle difference between them in the mudras, or the position of the hands. There are five groups of mudra: North, East, South, West and Zenith, which represent the five cardinal compass points according to Mahayana. The first four balustrades have the first four mudras: North, East, South and West, of which the Buddha statues that face one compass direction have the corresponding mudra. Buddha statues at the fifth balustrades and inside the 72 stupas on the top platform have the same mudra: Zenith. Each mudra represents one of the Five Dhyani Buddhas; each has its own symbolism.[103]

Following the order of Pradakshina (clockwise circumumbulation) starting from the East, the mudras of the Borobudur buddha statues are:

| Statue | Mudra | Symbolic meaning | Dhyani Buddha | Cardinal Point | Location of the Statue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Bhumisparsa mudra | Calling the Earth to witness | Aksobhya | East | Rupadhatu niches on the first four eastern balustrades |

|

Vara mudra | Benevolence, alms giving | Ratnasambhava | South | Rupadhatu niches on the first four southern balustrades |

|

Dhyana mudra | Concentration and meditation | Amitabha | West | Rupadhatu niches on the first four western balustrades |

|

Abhaya mudra | Courage, fearlessness | Amoghasiddhi | North | Rupadhatu niches on the first four northern balustrades |

|

Vitarka mudra | Reasoning and virtue | Vairochana | Zenith | Rupadhatu niches in all directions on the fifth (uppermost) balustrade |

|

Dharmachakra mudra | Turning the Wheel of dharma (law) | Vairochana | Zenith | Arupadhatu in 72 perforated stupas on three rounded platforms |

Legacy

The aesthetic and technical mastery of Borobudur, and also its sheer size, has evoked the sense of grandeur and pride for Indonesians. Just like Angkor Wat for Cambodian, Borobudur has become a powerful symbol for Indonesia — to testify for its past greatness. Sukarno made a point of showing the site to foreign dignitaries. The Suharto regime — realized its important symbolic and economic meanings — diligently embarked on a massive project to restore the monument with the help from UNESCO. Many museums in Indonesia contain a scale model replica of Borobudur. The monument has become almost an icon, grouped with the wayang puppet play and gamelan music into a vague classical Javanese past from which Indonesians are to draw inspiration.[104]

Several archaeological relics taken from Borobudur or its replica have been displayed in some museums in Indonesia and abroad. Other than Karmawibhangga Museum within Borobudur temple ground, some museums boast to host relics of Borobudur, such as Indonesian National Museum in Jakarta, Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam, British Museum in London, and Thai National Museum in Bangkok. Louvre museum in Paris, Malaysian National Museum in Kuala Lumpur, and Museum of World Religions in Taipei also displayed the replica of Borobudur.[91] The monument has drawn global attention to the classical Buddhist civilization of ancient Java.

The rediscovery and reconstruction of Borobudur has been hailed by Indonesian Buddhist as the sign of the Buddhist revival in Indonesia. In 1934, Narada Thera, a missionary monk from Sri Lanka, visited Indonesia for the first time as part of his journey to spread the Dharma in Southeast Asia. This opportunity was used by a few local Buddhists to revive Buddhism in Indonesia. A bodhi tree planting ceremony was held in Southeastern side of Borobudur on 10 March 1934 under the blessing of Narada Thera, and some Upasakas were ordained as monks.[105] Once a year, thousands of Buddhist from Indonesia and neighboring countries flock to Borobudur to commemorate national Vesak ceremony.[106]

The emblem of Central Java province and Magelang Regency bears the image of Borobudur. It has become the symbol of Central Java, and also Indonesia on a wider scale. Borobudur has become the name of several establishments, such as Borobudur University, Borobudur Hotel in Central Jakarta, and several Indonesian restaurants abroad. Borobudur has been featured in Rupiah banknote, stamps, numbers of books, publications, documentaries and Indonesian tourism promotion materials. The monument has become one of the main tourism attraction in Indonesia, vital for generating local economy in the region surrounding the temple. The tourism sector of the city of Yogyakarta for example, flourishes partly because of its proximity to Borobudur and Prambanan temples.

In literature

In her poem ![]()

Gallery

Gallery of reliefs

- Relief panel of a ship at Borobudur.

Musicians performing a musical ensemble, probably the early form of gamelan.

Musicians performing a musical ensemble, probably the early form of gamelan. The Apsara of Borobudur.

The Apsara of Borobudur. The scene of King and Queen with their subjects.

The scene of King and Queen with their subjects. One relief on a corridor wall.

One relief on a corridor wall. A weapon, probably the early form of keris.

A weapon, probably the early form of keris. A detailed carved relief stone.

A detailed carved relief stone.

Surasundari holding a lotus

Surasundari holding a lotus Close up of a relief

Close up of a relief%2C_1022a.jpg) Great Departure from Lalitavistara

Great Departure from Lalitavistara

Gallery of Borobudur

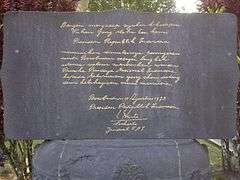

World Heritage inscription of Borobudur Temple

World Heritage inscription of Borobudur Temple The procedures signage for visiting Borobudur Temple

The procedures signage for visiting Borobudur Temple The inscription of Borobudur restoration in 1973 by the former Indonesian president Soeharto

The inscription of Borobudur restoration in 1973 by the former Indonesian president Soeharto The scattered parts of Borobudur Temple at Karmawibhangga Museum. People still can't locate their original positions.

The scattered parts of Borobudur Temple at Karmawibhangga Museum. People still can't locate their original positions. A Buddha statue inside a stupa

A Buddha statue inside a stupa

See also

Notes

- "Largest Buddhist temple". Guinness World Records. Guinness World Records. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- Purnomo Siswoprasetjo (4 July 2012). "Guinness names Borobudur world's largest Buddha temple". The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on 5 November 2014. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- "Borobudur Temple Compounds". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. UNESCO. Retrieved 28 December 2008.

- Soekmono (1976), page 35–36.

- "Borobudur : A Wonder of Indonesia History". Indonesia Travel. Archived from the original on 14 April 2012. Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- Le Huu Phuoc (April 2010). Buddhist Architecture. Grafikol. Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- Soekmono (1976), page 4.

- Hary Gunarto, Preserving Borobudur's Narrative Walls of UNESCO Heritage, Ritsumeikan RCAPS Occasional Paper, October 2007

- Mark Elliott; et al. (November 2003). Indonesia. Melbourne: Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd. pp. 211–215. ISBN 1-74059-154-2.

- Mark P. Hampton (2005). "Heritage, Local Communities and Economic Development". Annals of Tourism Research. 32 (3): 735–759. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2004.10.010.

- E. Sedyawati (1997). "Potential and Challenges of Tourism: Managing the National Cultural Heritage of Indonesia". In W. Nuryanti (ed.). Tourism and Heritage Management. Yogyakarta: Gajah Mada University Press. pp. 25–35.

- Soekmono (1976), page 13.

- Thomas Stamford Raffles (1817). The History of Java (1978 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-580347-7.

- J. L. Moens (1951). "Barabudur, Mendut en Pawon en hun onderlinge samenhang (Barabudur, Mendut and Pawon and their mutual relationship)" (PDF). Tijdschrift voor de Indische Taai-, Land- en Volkenkunde. Het Bataviaasch Genootschap van Kunsten en Wetenschappen: 326–386. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 August 2007.

trans. by Mark Long

- J.G. de Casparis, "The Dual Nature of Barabudur", in Gómez and Woodward (1981), page 70 and 83.

- "Borobudur" (in Indonesian). Indonesian Embassy in Den Haag. 21 December 2012. Archived from the original on 6 November 2014. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- Drs. R. Soekmono (1988) [1973]. Pengantar Sejarah Kebudayaan Indonesia 2, 2nd ed (5th reprint ed.). Yogyakarta: Penerbit Kanisius. p. 46.

- Walubi. "Borobudur: Candi Berbukit Kebajikan". Archived from the original on 3 July 2010. Retrieved 9 December 2009.

- Soekmono (1976), page 1.

- N. J. Krom (1927). Borobudur, Archaeological Description. The Hague: Nijhoff. Archived from the original on 17 August 2008. Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- Murwanto, H.; Gunnell, Y; Suharsono, S.; Sutikno, S. & Lavigne, F (2004). "Borobudur monument (Java, Indonesia) stood by a natural lake: chronostratigraphic evidence and historical implications". The Holocene. 14 (3): 459–463. Bibcode:2004Holoc..14..459M. doi:10.1191/0959683604hl721rr.

- Soekmono (1976), page 9.

- Miksic (1990)

- Laguna Copperplate Inscription

- Ligor inscription

- Coedès, George (1968). Walter F. Vella, ed. The Indianized States of Southeast Asia. trans.Susan Brown Cowing. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1.

- Dumarçay (1991).

- Paul Michel Munoz (2007). Early Kingdoms of the Indonesian Archipelago and the Malay Peninsula. Singapore: Didier Millet. p. 143. ISBN 981-4155-67-5.

- W. J. van der Meulen (1977). "In Search of "Ho-Ling"". Indonesia. 23: 87–112. doi:10.2307/3350886.

- W. J. van der Meulen (1979). "King Sañjaya and His Successors". Indonesia. 28 (28): 17–54. doi:10.2307/3350894. hdl:1813/53687. JSTOR 3350894.

- Soekmono (1976), page 10.

- D.G.E. Hall (1956). "Problems of Indonesian Historiography". Pacific Affairs. 38 (3/4): 353–359. doi:10.2307/2754037. JSTOR 2754037.

- Roy E. Jordaan (1993). Imagine Buddha in Prambanan: Reconsidering the Buddhist Background of the Loro Jonggrang Temple Complex. Leiden: Vakgroep Talen en Culturen van Zuidoost-Azië en Ocenanië, Rijksuniversiteit te Leiden. ISBN 90-73084-08-3.

- "Wacana Nusantara - Candi Borobudur". Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- Soekmono (1976), page 5.

- Soekmono (1976), page 6.

- Soekmono (1976), page 42.

- W.P. Groeneveldt at parlement.com

- John Miksic; Marcello Tranchini; Anita Tranchini (1996). Borobudur: Golden Tales of the Buddhas. Tuttle publishing. p. 29. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- "Borobudur Pernah Salah Design?" (in Indonesian). Kompas. 7 April 2000. Archived from the original on 26 December 2007. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- Soekmono (1976), page 43.

- "UNESCO experts mission to Prambanan and Borobudur Heritage Sites" (Press release). UNESCO. 31 August 2004.

- "Saving Borobudur". PBS. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- Caesar Voute; Voute, Caesar (1973). "The Restoration and Conservation Project of Borobudur Temple, Indonesia. Planning: Research: Design". Studies in Conservation. 18 (3): 113–130. doi:10.2307/1505654. JSTOR 1505654.

- "Agreement concerning the voluntary contributions to be given for the execution of the project to preserve Borobudur" (PDF).

- "Cultural heritage and partnership; 1999" (PDF) (Press release). UNESCO. Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- Post, The Jakarta. "UI archaeology professor weighs in on Borobudur's 'chattra' restoration". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- Vaisutis, Justine (2007). Indonesia. Lonely Planet. p. 856. ISBN 1-74104-435-9.

- "The Meaning of Procession". Waisak. Walubi (Buddhist Council of Indonesia). Archived from the original on 11 February 2009. Retrieved 28 December 2008.

- Jamie James (27 January 2003). "Battle of Borobudur". Time. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- "Candi Borobudur dicatatkan di Guinness World Records" (in Indonesian). AntaraNews.com. 5 July 2012. Archived from the original on 9 July 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- "Section II: Periodic Report on the State of Conservation" (PDF). State of Conservation of the World Heritage Properties in the Asia-Pacific Region. UNESCO World Heritage. Retrieved 23 February 2010.

- "Batu Tangga Candi Borobudur akan Dilapisi Kayu" (in Indonesian). National Geographic Indonesia. 19 August 2014. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- "Covered in volcanic ash, Borobudur closed temporarily". from, Magelang, C Java (by ANTARA News). 6 November 2010. Archived from the original on 9 November 2010. Retrieved 6 November 2010.

- "Borobudur Temple Forced to Close While Workers Remove Merapi Ash". Jakarta Globe. 7 November 2010. Archived from the original on 11 November 2010. Retrieved 7 November 2010.

- "Inilah Foto-foto Kerusakan Candi" (in Indonesian). Tribun News. 7 November 2010. Retrieved 7 November 2010.

- "Borobudur's post-Merapi eruption rehabilitating may take three years: Official". 17 February 2011. Archived from the original on 16 January 2016.

- "Borobudur clean-up to finish in November". The Jakarta Post. 28 June 2011. Retrieved 28 June 2012.

- "Stone Conservation Workshop, Borobudur, Central Java, Indonesia, 11-12 January 2012 funded by the Federal Republic of Germany - | UNESCO Office in Jakarta". Portal.unesco.org. 16 January 2012. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- "Germany Supports Safeguarding of Borobudur". The Jakarta Globe. Archived from the original on 15 June 2012. Retrieved 28 June 2012.

- "Borobudur, Other Sites, Closed After Mount Kelud Eruption". JakartaGlobe. 14 February 2014. Archived from the original on 14 February 2014. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

- "1,100-Year-Old Buddhist Temple Wrecked By Bombs in Indonesia". The Miami Herald. 22 January 1985. Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- "Teror Bom di Indonesia (Beberapa di Luar Negeri) dari Waktu ke Waktu" (in Indonesian). Tempo Interaktif.com. 17 April 2004. Archived from the original on 17 September 2011. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- Harold Crouch (2002). "The Key Determinants of Indonesia's Political Future" (PDF). Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. 7. ISSN 0219-3213. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 March 2015.

- Sebastien Berger (30 May 2006). "An ancient wonder reduced to rubble". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- Ika Fitriana (22 August 2014). "Terkait Ancaman ISIS di Media Sosial, Pengamanan Candi Borobudur Diperketat" (in Indonesian). National Geographic Indonesia. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- Ika Fitriana (19 November 2014). "Tangga Candi Borobudur Mulai Dilapisi Kayu". Kompas.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 14 October 2015.

- I Made Asdhiana, ed. (6 March 2015). "Tangga Candi Borobudur Dilapisi Karet". Kompas.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 14 October 2015.

- Sugiyanto (13 October 2015). "Cegah Keausan Batu, Pengunjung Borobudur Diharuskan Pakai Sandal Khusus".

- John N. Miksic; Marcello Tranchini. Borobudur: Golden Tales of the Buddhas, Periplus Travel Guides Series. Tuttle Publishing, 1990. p. 46. ISBN 0-945971-90-7. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

- A. Wayman (1981). "Reflections on the Theory of Barabudur as a Mandala". Barabudur History and Significance of a Buddhist Monument. Berkeley: Asian Humanities Press.

- Vaisutis, Justine (2007). Indonesia. Victoria: Lonely Planet Publications. p. 168. ISBN 1-74104-435-9.

- "Pangguyangan". Dinas Pariwisata dan Budaya Provinsi Jawa Barat (in Indonesian).

- I.G.N. Anom; Sri Sugiyanti; Hadniwati Hasibuan (1996). Maulana Ibrahim; Samidi (eds.). Hasil Pemugaran dan Temuan Benda Cagar Budaya PJP I (in Indonesian). Direktorat Jenderal Kebudayaan. p. 87.

- Timbul Haryono (2011). Sendratari mahakarya Borobudur (in Indonesian). Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia. p. 14. ISBN 9789799103338.

- R. Soekmono (2002). Pengantar Sejarah Kebudayaan Indonesia 2 (in Indonesian). Kanisius. p. 87. ISBN 9789794132906.

- "Kebudayaan Megalithikum Prof. Dr. Sutjipto Wirgosuparto". E-dukasi.net. Archived from the original on 10 July 2012. Retrieved 28 June 2012.

- Tartakov, Gary Michael. "Lecture 17: Sherman Lee's History of Far Eastern Art (Indonesia and Cambodja)". Lecture notes for Asian Art and Architecture: Art & Design 382/582. Iowa State University. Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- Soekmono (1976), page 17.

- Peter Ferschin & Andreas Gramelhofer (2004). "Architecture as Information Space". 8th Int. Conf. on Information Visualization. IEEE. pp. 181–186. doi:10.1109/IV.2004.1320142.

- Soekmono (1976), page 18.

- Soekmono (1976), page 16.

- Caesar Voûte & Mark Long. Borobudur: Pyramid of the Cosmic Buddha. D.K. Printworld Ltd. Archived from the original on 8 June 2008. Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- Atmadi (1988).

- H. Situngkir (2010). "Borobudur Was Built Algorithmically". BFI Working Paper Series WP-9-2010. Bandung Fe Institute. SSRN 1672522.

- "Borobudur". Buddhist Travel. 2008. Archived from the original on 5 January 2012. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- Tom Cockrem (2008). "Temple of enlightenment". The Buddhist Channel.tv. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- "The Cinnamon Route". Borobudur Park. Archived from the original on 25 September 2010. Retrieved 14 December 2011.

- "The Borobudur Ship Expedition, Indonesia to Africa 2003–2004". The Borobudur Ship Expedition. 2004. Archived from the original on 17 February 2003. Retrieved 14 December 2011.

- "Surasundari". Art and Archaeology.com. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- "The Greatest Sacred Buildings". Museum of World Religions, Taipei. Archived from the original on 7 February 2017. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- Soekmono (1976), page 20.

- Jaini, P.S. (1966). "The Story of Sudhana and Manohara: An Analysis of the Texts and the Borobudur Reliefs". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 29 (3): 533–558. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00073407. ISSN 0041-977X. JSTOR 611473.

- Soekmono (1976), page 21.

- Soekmono (1976), page 26.

- "Jataka". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- Soekmono (1976), page 29.

- Soekmono (1976), page 32.

- Soekmono (1976), page 35.

- Hiram W. Woodward Jr. (1979). "Acquisition". Critical Inquiry. 6 (2): 291–303. doi:10.1086/448048.

- "Borobudur Buddha head". BBC. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

A History of The World, The British Museum

- Muryanto, Bambang (20 November 2014). "Buddhas to be reunited with their heads". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- Roderick S. Bucknell & Martin Stuart-Fox (1995). The Twilight Language: Explorations in Buddhist Meditation and Symbolism. UK: Routledge. ISBN 0-7007-0234-2.

- Wood, Michael (2011). "Chapter 2: Archaeology, National Histories, and National Borders in Southeast Asia". In Clad, James; McDonald, Sean M.; Vaughan, Bruce (eds.). The Borderlands of Southeast Asia. NDU Press. p. 38.

- "Buddhism in Indonesia". Buddhanet. Archived from the original on 14 February 2002. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- "Vesak Festival: A Truly Sacred Experience". Wonderful Indonesia. Archived from the original on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

References

- Peter Cirtek (2016). Borobudur: Appearance of a Universe. Hamburg: Monsun Verlag. ISBN 978-3-940429-06-3.

- Parmono Atmadi (1988). Some Architectural Design Principles of Temples in Java: A study through the buildings projection on the reliefs of Borobudur temple. Yogyakarta: Gajah Mada University Press. ISBN 979-420-085-9.

- Jacques Dumarçay (1991). Borobudur. trans. and ed. by Michael Smithies (2nd ed.). Singapore: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-588550-3.

- Luis O. Gómez & Hiram W. Woodward, Jr. (1981). Barabudur: History and Significance of a Buddhist Monument. Berkeley: Univ. of California. ISBN 0-89581-151-0.

- John Miksic (1990). Borobudur: Golden Tales of the Buddhas. Boston: Shambhala Publications. ISBN 0-87773-906-4.

- Soekmono (1976). Chandi Borobudur: A Monument of Mankind (PDF). Paris: Unesco Press. ISBN 92-3-101292-4. Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- R. Soekmono; J.G. de Casparis; J. Dumarçay; P. Amranand; P. Schoppert (1990). Borobudur: A Prayer in Stone. Singapore: Archipelago Press. ISBN 2-87868-004-9.

Further reading

- Luis O. Gomez & Hiram W. Woodward (1981). Barabudur, history and significance of a Buddhist monument. presented at the Int. Conf. on Borobudur, Univ. of Michigan, 16–17 May 1974. Berkeley: Asian Humanities Press. ISBN 0-89581-151-0.

- August J.B. Kempers (1976). Ageless Borobudur: Buddhist mystery in stone, decay and restoration, Mendut and Pawon, folklife in ancient Java. Wassenaar: Servire. ISBN 90-6077-553-8.

- John Miksic (1999). The Mysteries of Borobudur. Hongkong: Periplus. ISBN 962-593-198-8.

- Morton III, W. Brown (January 1983). "Indonesia Rescues Ancient Borobudur". National Geographic. 163 (1): 126–142. ISSN 0027-9358. OCLC 643483454.

- Adrian Snodgrass (1985). The symbolism of the stupa. Southeast Asia Program. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University. ISBN 0-87727-700-1.

- Levin, Cecelia. "Enshrouded in Dharma and Artha: The Narrative Sequence of Borobudur’s First Gallery Wall." In Materializing Southeast Asia's Past: Selected Papers from the 12th International Conference of the European Association of Southeast Asian Archaeologists, edited by Klokke Marijke J. and Degroot Véronique, 27-40. SINGAPORE: NUS Press, 2013. Accessed June 17, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv1qv3kf.7.

- Jaini, Padmanabh S. "The Story of Sudhana and Manoharā: An Analysis of the Texts and the Borobudur Reliefs." Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 29, no. 3 (1966): 533-58. Accessed June 17, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/611473.

- Shastri, Bahadur Chand. “THE IDENTIFICATION OF THE FIRST SIXTEEN RELIEFS ON THE SECOND MAIN-WALL OF BARABUDUR.” Bijdragen Tot De Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde Van Nederlandsch-Indië, vol. 89, no. 1, 1932, pp. 173–181. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/20770599. Accessed 24 Apr. 2020.

- SUNDBERG, JEFFREY ROGER. "Considerations on the Dating of the Barabuḍur Stūpa." Bijdragen Tot De Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde 162, no. 1 (2006): 95-132. Accessed June 17, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/27868287.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Borobudur. |

- Official site of Borobudur, Prambanan, and Ratu Boko Park

- UNESCO Site

- Borobudur Temple Compounds short documentary by UNESCO and NHK

- Wonderful Indonesia's Guide on Borobudur

- Learning From Borobudur documentary about Borobudur's bas-reliefs stories of Jatakas, Lalitavistara and Gandavyuha in YouTube

- Australian National University's research project on Borobudur

- Analysis of Borobudur's hidden base

- Explore Borobudur on Global Heritage Network

- Photographs of Borobudur Stupa

- "Yogyakarta. Temple Ruins: Details of Sculpted Figures" is a photograph with commentary by Frank G. Carpenter.

- Wacana Nusantara