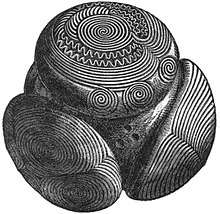

Carved stone balls

Carved stone balls are petrospheres dated from the late Neolithic to possibly as late as the Iron Age mainly found in Scotland, but also elsewhere in Britain and Ireland. They are usually round and rarely oval, and of fairly uniform size at around 2.75 inches or 7 cm across, with 3 to 160 protruding knobs on the surface. They range from having no ornamentation (apart from the knobs) to extensive and highly varied engraved patterns.[2] A wide range of theories have been produced to explain their use or significance, with none gaining very wide acceptance.

They are not to be confused with the much larger smooth round stone spheres of Costa Rica.

Age and distribution

Carved stone balls are up to 5200 years old, coming from the late Neolithic to at least the Bronze Age.[3]

Nearly all have been found in north-east Scotland, the majority in Aberdeenshire, the fertile land lying to the east of the Grampian Mountains. A similar distribution to that of Pictish symbols led to the early suggestion that carved stone balls are Pictish artefacts.[4] The core distribution also reflects that of the Recumbent stone circles. As objects they are very easy to transport and a few have been found on Iona, Skye, Harris, Uist, Lewis, Arran, Hawick, Wigtownshire and fifteen from Orkney. Outside Scotland examples have been found in Ireland at Ballymena, and in England at Durham, Cumbria, Lowick and Bridlington. The larger (90mm diameter) balls are all from Aberdeenshire, bar one from Newburgh in Fife.

By the late 1970s a total of 387 had been recorded.[4] Of these, by far the greatest concentration (169) was found in Aberdeenshire. By 1983 the number had risen to 411[5] and by 2015 over 425 balls had been recorded.[3] A collection of over 30 carved balls from Scotland, Ireland and northern England are held by the British Museum.[6]

Archaeological context

Many of the balls have not had their discovery site recorded and most are found as a result of agricultural activity. Five were found at the Neolithic settlement of Skara Brae and one at the Dunadd hillfort. The distribution of the balls is similar to that of mace-heads, which were both weapons and prestige objects used in ceremonial situations.[7] The lack of context is likely to distort the interpretation. Random finds are only likely to have been picked up and entered a collection if they were aesthetically appealing. Damaged and plain balls were less likely to find a market than decorated examples so some more decorated examples might be fraudulent.

In 2013, archaeologists discovered a carved stone ball at Ness of Brodgar, a rare find of such an object in situ in "a modern archaeological context".[8]

Physical characteristics

Materials

Many are said to be made of "greenstone", but this is a general term for all varieties of dark, greenish igneous rocks, including diorites, serpentinite, and altered basalts. Forty-three are sandstone, including Old Red Sandstone, 26 greenstone and 12 quartzite. Nine were serpentinite and these had been carved. Some were made of gabbro, a difficult material to carve. Round and oval natural shaped sandstones are sometimes found. Examples made from Hornblende gneiss and granitic gneiss were noted, both very difficult stone to work. Granitic rocks were also used and the famous Towie example may be serpentinised picrite. The highly ornamented examples were mainly made of sandstone or serpentine.[9] A significant number have not as yet been fully inspected or tested to ascertain their composition.

Experimental archaeology

Using authentic manufacturing techniques (pecking and grinding), full replicas have been made by Andrew T. Young, a researcher at the University of Exeter. It was shown that they could be made using prehistoric technology with no recourse to the use of metal tools.[10]

Size, shape and knobs

Of the 387 carved stone balls known in 1976 (now about 425), 375 are about 70 mm in diameter, but twelve are known with diameters of 90 to 114 mm. Only 7 are oval. They are therefore about the size of tennis balls or oranges.

Nearly half have 6 knobs, 3 have 3 knobs, 43 have 4 knobs, 3 have 5 knobs, 18 have 7 knobs, 9 have 8 knobs, 3 have 9 knobs, 52 have between 10 and 55 knobs and finally 14 have between 70 and 160 knobs.

Ornamentation

The decoration used falls into three categories, those with spirals, those with concentric circles and those with patterns of straight incised lines and hatchings. More than one design is used on the same ball and the standard of artwork varies from the extremely crude to the highly expert which only an exceptionally skilled craftsman could have produced. Some balls have designs on the interspaces between the knobs which must be significant in the context of the speculated use of these artefacts. Twenty-six of the six-knobbed balls are decorated. The Orkney examples are unusual, being either all ornamented or otherwise unusual in appearance, such as the lack, bar one example, of the frequently found six-knobbed type. Metal may have been used to work some of the designs.

The Towie ball has some design similarities with the carvings on the Folkton Drums. These were found in a tumulus in England and are made of chalk with elaborate carvings, amongst which are distinct oculi or eyes.[11] Concentric carved lines on stone balls appear to be stylised oculi. This ball also has a roughly triangular arrangement of three dots in an interspace between the knobs. This appears to be identical to the arrangement of dots found on the Parkhill silver chain terminal ring, found near Aberdeen, a Pictish artefact. It is possible that the dots represent a name, as some of the Pictish symbols at least are thought to represent personal names.[12]

Spirals or plastic ornament which is similar to Grooved Ware is found on the Aberdeenshire examples, this being a type of late Neolithic pottery not known in the north-east but common in Orkney and Fife. The New Grange carvings in Ireland show strong similarities to those found on some balls. A continuous spiral is found on one and elements of chevrons, zig-zags and concentric triangles are also found, stimulating comparisons with petrosomatoglyph symbolism. Mostly the different knobs have different or sometimes no ornamentation. A 'golf-ball' variety of ornamentation is found on a few balls. The carving does not appear to have any practical purpose in general, however it has been suggested that one type, with very distinct knobs, was used for processing copper ores (see under 'Function'). Some of the bold triangles and criss-cross incisions seem to be more Iron Age in character than Neolithic or Bronze Age.[13]

Function

Some of the balls have grooves or interspaces between the knobs into which leather could be tied so as to make a device such as a bolas. Their use as weapons was suggested by many researchers but in recent years this idea has fallen from favour.

One suggestion saw the balls as movable poises on a primitive weighing machine, following the logic of the remarkable uniformity in size shown by a good number of these carefully made objects. However, it has been shown that their weights vary so considerably that mathematically they could not be considered part of a system of weight measurement.

'Sink stones' found in Denmark and Ireland have some slight similarities, these artefacts being used in conjunction with fishing nets.[14]

The possible use of the balls as oracles has been suggested. The way in which the ball came to rest could be interpreted as a message from the gods or an answer to a question. The lack of balls found in graves may indicate that they were not considered to belong to individuals.

An alternative or supplementary use could have been as the 'right to speak' where discussions are controlled by the requirement for the speaker to hold the carved stone ball or if not, then keep his or her peace and listen to the views of others. The balls are of a size that fits comfortably in one hand.

Another possible use for the stones would be in the working of hides. Into the 20th century leatherworkers polished leather, parchment, and hides, by tying the skins to a frame using a ball at each corner of the hide then rubbing down material being worked with stones. The corners of the hides were wrapped around the balls which allowed the bindings to hold fast without slipping off. In more modern times, the balls were often made from scraps of the material being worked and the leather was cut away from the balls when the polishing was finished. This caused the balls to grow in size until the process had to be started over by replacing the oversized balls with scraps and beginning a new ball.

Balls of plain sandstone with the facets from shaping still clearly visible were found at Traprain Law in East Lothian. A significant number have already been found here and are known from other southern Scottish Iron Age sites. They may date from the fourth to third centuries BC. These balls are not ornamented and do not have knobs.[15]

Megalith construction aid

A theory on the movement of 'monument stones' has been put forward as a result of an observed correlation between standing stone circles in Aberdeenshire, Scotland and a concentration of carved stone balls, and it is suggested that these petrospheres may have been used to help transport the big stones by functioning like ball bearings.

Many of the late Neolithic stone balls have diameters differing by only a millimetre. The discovery of this led to the suggestion that they might have been meant to be used together. By plotting the find sites on a map it can be demonstrated that often these petrospheres were located in the vicinity of Neolithic recumbent stone circles. Models using small wooden balls placed in a groove in parallel longitudinal pieces of wood 'sleepers' with a carrying board above have shown such megalith transport to be practical in some situations.[16]

Platonic solids

The carved stone balls have been taken as evidence of knowledge of the five Platonic solids a millennium before Plato described them. Indeed, some of them exhibit the symmetries of Platonic solids, but the extent of this and how much it depends on mathematical understanding is disputed, as configurations resembling the solids can naturally arise when placing knobs around a sphere. There does not appear to be much special attention given to the Platonic solid arrangements over less symmetrical arrangements of knobs over the balls, and some of the five solids do not appear.[17][18]

See also

- List of prehistoric artworks

- Dodecahedra

- Roman dodecahedron

References

- "Carved stone ball". National Museums of Scotland. Retrieved 22 March 2008.

- Marshall, D. N. (1976/77). "Carved Stone Balls". Proc Soc Antiq Scot, 108, Pp. 4–72.

- http://www.ashmolean.org/ash/britarch/highlights/stone-balls.html

- Marshall, D.N. (1976/77). Carved Stone Balls. Proc Soc Antiq Scot, 108, P. 55.

- Marshall, D. N. (1983). "Further notes on Carved Stone Balls". Proc Soc Antiq Scot, 113, pp. 628-646.

- British Museum Collection

- Marshall, D.N. (1976/77). Carved Stone Balls. Proc Soc Antiq Scot, 108, P. 62 – 63.

- "Dig Diary — Wednesday, August 7, 2013" Archived 25 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Orkneyjar. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- Marshall, D.N. (1976/77). Carved Stone Balls. Proc Soc Antiq Scot, 108, P. 54.

- University of Exter, The Ground Stone Tools of Britain and Ireland: an Experimental Approach von Andrew T. Young, retrieved 30. August 2014

- Powell, T. G. E. (1966). Prehistoric Art. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-20046-7

- Cummins, W. A. (1999). The Picts and their Symbols. Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-2207-9. P. 92.

- Marshall, D. N. (1976/77). Carved Stone Balls. Proc Soc Antiq Scot, 108, P. 62.

- Evans, Sir John (1897). The Ancient Stone Implements, weapons and ornaments of Great Britain. Pub. Longmans, Green & Co. 2nd Edition. P. 422.

- Rees, Thomas & Hunter, Fraser (2000). Archaeological excavation of a medieval structure and an assemblage of prehistoric artefacts from the summit of Traprain Law, East Lothian. 1996 - 7. PSAS 130, P. 413 - 440.

- "Discovering the Secrets of Stonehenge". Science Daily. 20 November 2010. Retrieved 8 July 2011.

- Lloyd 2012.

- Hart, George. "Neolithic Carved Stone Polyhedra".

Sources

- Smith, John Alexander (1874–76) Notes of Small Ornamented Stone Balls found in different parts of Scotland, &c., with Remarks on their supposed Age and Use. PSAS V. 11, P.29 - 62.

- Smith, John Alexander (1874–76) Additional notes of Small Ornamented Stone Balls found in different parts of Scotland, &c., PSAS V. 11, P.313 - 319.

- Lloyd, David Robert (2012). "How old are the Platonic Solids?". BSHM Bulletin: Journal of the British Society for the History of Mathematics. 27 (3): 131–140. doi:10.1080/17498430.2012.670845.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carved stone balls from Prehistoric Britain. |