Art exhibition

An art exhibition is traditionally the space in which art objects (in the most general sense) meet an audience. The exhibit is universally understood to be for some temporary period unless, as is rarely true, it is stated to be a "permanent exhibition". In American English, they may be called "exhibit", "exposition" (the French word) or "show". In UK English, they are always called "exhibitions" or "shows", and an individual item in the show is an "exhibit".

.jpg)

Such expositions may present pictures, drawings, video, sound, installation, performance, interactive art, new media art or sculptures by individual artists, groups of artists or collections of a specific form of art.

The art works may be presented in museums, art halls, art clubs or private art galleries, or at some place the principal business of which is not the display or sale of art, such as a coffeehouse. An important distinction is noted between those exhibits where some or all of the works are for sale, normally in private art galleries, and those where they are not. Sometimes the event is organized on a specific occasion, like a birthday, anniversary or commemoration.

Types of exhibitions

There are different kinds of art exhibitions, in particular there is a distinction between commercial and non-commercial exhibitions. A commercial exhibition or trade fair is often referred to as an art fair that shows the work of artists or art dealers where participants generally have to pay a fee. A vanity gallery is an exhibition space of works in a gallery that charges the artist for use of the space. Temporary museum exhibitions typically display items from the museum's own collection on a particular period, theme or topic, supplemented by loans from other collections, mostly those of other museums. They normally include no items for sale; they are distinguished from the museum's permanent displays, and most large museums set aside a space for temporary exhibitions.

Exhibitions in commercial galleries are often entirely made up of items that are for sale, but may be supplemented by other items that are not. Typically, the visitor has to pay (extra on top of the basic museum entrance cost) to enter a museum exhibition, but not a commercial one in a gallery. Retrospectives look back over the work of a single artist; other common types are individual exhibitions or "solo shows", and group exhibitions or "group shows"). The Biennale is a large exhibition held every two years, often intending to gather together the best of international art; there are now many of these. A travelling exhibition is an exhibition seen at several venues, sometimes across the world.

Exhibitions of new or recent art can be juried, invitational, or open.

- A juried exhibition, such as the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition in London, or the Iowa Biennial, has an individual (or group) acting as judge of the submitted artworks, selecting which are to be shown. If prizes are to be awarded, the judge or panel of judges will usually select the prizewinners as well.

- In an invitational exhibition, such as the Whitney Biennial, the organizer of the show asks certain artists to supply artworks and exhibits them.

- An open or "non-juried" exhibition, such as the Kyoto Triennial,[1] allows anybody to enter artworks and shows them all. A type of exhibition that is usually non-juried is a mail art exhibition.

History

The art exhibition has played a crucial part in the market for new art since the 18th and 19th centuries. The Paris Salon, open to the public from 1737, rapidly became the key factor in determining the reputation, and so the price, of the French artists of the day. The Royal Academy in London, beginning in 1769, soon established a similar grip on the market, and in both countries artists put great efforts into making pictures that would be a success, often changing the direction of their style to meet popular or critical taste. The British Institution was added to the London scene in 1805, holding two annual exhibitions, one of new British art for sale, and one of loans from the collections of its aristocratic patrons. These exhibitions received lengthy and detailed reviews in the press, which were the main vehicle for the art criticism of the day. Critics as distinguished as Denis Diderot and John Ruskin held their readers attention by sharply divergent reviews of different works, praising some extravagantly and giving others the most savage put-downs they could think of. Many of the works were already sold, but success at these exhibitions was a crucial way for an artist to attract more commissions. Among important early one-off loan exhibitions of older paintings were the Art Treasures Exhibition, Manchester 1857, and the Exhibition of National Portraits in London, at what is now the Victoria and Albert Museum, held in three stages in 1866-68.

As the academic art promoted by the Paris Salon, always more rigid than London, was felt to be stifling French art, alternative exhibitions, now generally known as the Salon des Refusés ("Salon of the Refused") were held, most famously in 1863, when the government allowed them an annex to the main exhibition for a show that included Édouard Manet's Luncheon on the Grass (Le déjeuner sur l’herbe) and James McNeill Whistler's Girl in White. This began a period where exhibitions, often one-off shows, were crucial in exposing the public to new developments in art, and eventually Modern art. Important shows of this type were the Armory Show in New York City in 1913 and the London International Surrealist Exhibition in 1936.

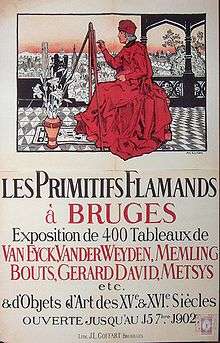

Museums started holding large loan exhibitions of historic art in the late 19th century, as also did the Royal Academy, but the modern "blockbuster" museum exhibition, with long queues and a large illustrated catalogue, is generally agreed to have been introduced by the exhibitions of artifacts from the tomb of Tutankhamun held in several cities in the 1970s. Many exhibitions, especially in the days before good photographs were available, are important in stimulating research in art history; the exhibition held in Bruges in 1902 (poster illustrated below) had a crucial impact on the study of Early Netherlandish painting.

In 1968 Art fairs in Europe became quite the fashion with the advent of the Cologne Art Fair which was sponsored by the Cologne Art Dealers Association. Because of the high admission standards of the Cologne fair a rival fair was organized in Düsseldorf which enabled less regarded galleries opportunity to meet with an international public. The fairs took place during the fall months. This rivalry continued for a few years which provided the Basel Art Fair the opportunity to interject the Basel fair in early summer. These fairs became extremely important to galleries, dealers and publishers as they provided the possibility of worldwide distribution. Düsseldorf and Cologne merged their efforts. Basel soon became the most important art fair.

In 1976, the Felluss Gallery under the direction of Elias Felluss, in Washington DC organized the first American dealer art fair. "The Washington International Art Fair" or "Wash Art" for brevity. This American fair met with fierce opposition by those galleries interested in maintaining distribution channels for European artwork already in place. The Washington fair introduced the European idea of dealer fairs to art dealers throughout the United States. Following the advent of Wash Art, many fairs developed throughout the United States.

Preservation issues

Although preservation issues are often disregarded in favor of other priorities during the exhibition process, they should certainly be considered so that possible damage to the collection is minimized or limited. As all objects in the library exhibition are unique and to some extent vulnerable, it is essential that they be displayed with care. Not all materials are able withstand the hardships of display, and therefore each piece needs to be assessed carefully to determine its ability to withstand the rigors of an exhibition. In particular, when exhibited items are archival artifacts or paper-based objects, preservation considerations need be emphasized because damage and change in such materials is cumulative and irreversible.[2] Two trusted sources – the National Information Standard Organization's[3] Environmental Conditions for Exhibiting Library and Archival Materials, and the British Library's Guidance for Exhibiting Library and Archive Materials – have established indispensable criteria to help curtail the deleterious effects of exhibitions on library and archival materials. These criteria may be divided into five main preservation categories: Environmental concerns of the exhibition space; Length of the exhibition; Individual cases; Display methods used on individual objects; and Security.

Environmental concerns of the exhibition space

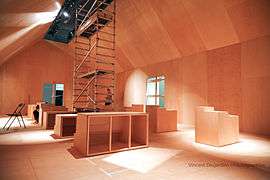

- Preparation for Richard Prince, American Prayer exhibition at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

1 February 2011

1 February 2011 25 February 2011

25 February 2011 25 February 2011

25 February 2011 8 March 2011

8 March 2011 26 June 2011

26 June 2011 26 June 2011

26 June 2011

The main concerns of exhibition environments include light, relative humidity, and temperature.

- Light

Light wavelength, intensity, and duration contribute collectively to the rate of material degradation in exhibitions.[4] The intensity of visible light in the display space should be low enough to avoid object deterioration, but bright enough for viewing. A patron’s tolerance of low level illumination can be aided by reducing ambient light levels to a level lower than that falling on the exhibit.[5] Visible light levels should be maintained at between 50 lux and 100 lux depending on the light sensitivity of objects.[6] An items level of toleration will depend on the inks or pigments being exposed and the duration of the exhibition time. A maximum exhibition length should initially be determined for each exhibited item based on its light sensitivity, anticipated light level, and its cumulative past and projected exhibition exposure.

Light levels need to be measured when the exhibition is prepared. UV light meters will check radiation levels in an exhibit space, and data event loggers help determine visible light levels over an extended period of time. Blue wool standards cards can also be utilized to predict the extent to which materials will be damaged during exhibits.[7] UV radiation must be eliminated to the extent it is physically possible; it is recommended that light with a wavelength below 400 nm (ultraviolet radiation) be limited to no more than 75 microwatts per lumen at 10 to 100 lux.[8] Furthermore, exposure to natural light is undesirable because of its intensity and high UV content. When such exposure is unavoidable, preventative measures must be taken to control UV radiation, including the use of blinds, shades, curtains, UV filtering films, and UV-filtering panels in windows or cases. Artificial light sources are safer options for exhibition. Among these sources, incandescent lamps are most suitable because they emit little or no UV radiation.[9] Fluorescent lamps, common in most institutions, may be used only when they produce a low UV output and when covered with plastic sleeves before exhibition.[10] Though tungsten-halogen lamps are currently a favorite artificial lighting source, they still give off significant amounts of UV radiation; use these only with special UV filters and dimmers.[11] Lights should be lowered or turned off completely when visitors are not in the exhibition space.

- Relative humidity (RH)

The exhibition space's relative humidity (RH) should be set to a value between 35% and 50%.[12] The maximum acceptable variation should be 5% on either side of this range. Seasonal changes of 5% are also allowed. The control of relative humidity is especially critical for vellum and parchment materials, which are extremely sensitive to changes in relative humidity and may contract violently and unevenly if displayed in too dry an environment.

- Temperature

For preservation purposes, cooler temperatures are always recommended. The temperature of the display space should not exceed 72 °F.[13] A lower temperature of down to 50 °F can be considered safe for a majority of objects. The maximum acceptable variation in this range is 5 °F, meaning that the temperature should not go above 77 °F and below 45 °F. As temperature and relative humidity are interdependent, temperature should be reasonably constant so that relative humidity can be maintained as well. Controlling the environment with 24-hour air conditioning and dehumidification is the most effective way of protecting an exhibition from serious fluctuations.

Length of the exhibition

One factor that influences how well materials will fare in an exhibition is the length of the show. The longer an item is exposed to harmful environmental conditions, the more likely that it will experience deterioration. Many museums and libraries have permanent exhibitions, and installed exhibitions have the potential to be on the view without any changes for years.

Damage from a long exhibition is usually caused by light. The degree of deterioration is different for each respective object. For paper-based items, the suggested maximum length of time that they should be on display is three months per year, or 42 kilolux hours of light per year – whichever comes first.[14]

An exhibition log report, including records of the length of the exhibition time and the light level of the display, may prevent objects from being exhibited too frequently. Displayed items need to be inspected regularly for evidence of damage or change.[15] It is recommended that high-quality facsimiles of especially delicate or fragile materials be displayed in lieu of originals for longer exhibitions.[16]

Individual cases

Library or archival materials are usually displayed in display cases or frames. Cases provide a physically and chemically secure environment. Vertical cases are acceptable for small or single-sheet items, and horizontal cases can be used for a variety of objects, including three-dimensional items such as opened or closed books, and flat paper items. All these objects can be arranged simultaneously in one horizontal case under a unified theme.

Materials used for case construction should be chosen carefully because component materials can easily become a significant source of pollutants or harmful fumes for displayed objects. Outgassing from materials used in the construction of the exhibition case and/or fabrics used for lining the case can be destructive. Pollutants may cause visible deterioration, including discoloration of surfaces and corrosion. Examples of evaluative criteria to be used in deeming materials suitable for use in exhibit display could be the potential of contact-transfer of harmful substances, water solubility or dry-transfer of dyes, the dry-texture of paints, pH, and abrasiveness.[17]

New cases may be preferred, constructed of safe materials such as metal, plexiglass, or some sealed woods.[18] Separating certain materials from the display section of an exhibition case by lining relevant surfaces with an impermeable barrier film will help protect items from damage. Any fabrics that line or decorate the case (e.g. polyester blend fabric), and any adhesives used in the process, should also be tested to determine any risk. Using internal buffers and pollutant absorbers, such as silica gel, activated carbon, or zeolite, is a good way to control relative humidity and pollutants. Buffers and absorbers should be placed out of sight, in the base or behind the backboard of a case. If the case is to be painted, it is recommended oil paints be avoided; acrylic or latex paint is preferable.

Display methods

There are two kinds of objects displayed at the library and archival exhibition – bound materials and unbound materials. Bound materials include books and pamphlets, and unbound materials include manuscripts, cards, drawings, and other two-dimensional items. The observance of proper display conditions will help minimize any potential physical damage. All items displayed must be adequately supported and secured.

- Unbound materials

Unbound materials, usually single-sheet items, need to be attached securely to the mounts, unless matted or encapsulated. Metal fasteners, pins, screws, and thumbtacks should not come in direct contact with any exhibit items.[19] Instead, photo corners, polyethylene, or polyester film straps may hold the object to the support. Objects may also be encapsulated in polyester film, though old and untreated acidic papers should be professionally deacidified before encapsulation.[20] Avoid potential slippage during encapsulation – when possible, use ultrasonic or heat seals. For objects that need to be hung (and that may require more protection than lightweight polyester film), matting would be an effective alternative.

Objects in frames should be separated from harmful materials through matting, glazing, and backing layers. Matting, which consists of two pH-neutral or alkaline boards with a window cut in the top board to enable the object to be seen, can be used to support and enhance the display of single sheet or folded items. Backing layers of archival cardboard should be thick enough to protect objects. Moreover, any protective glazing used should never come in direct contact with objects.[21] Frames should be well-sealed and hung securely, allowing a space for air circulation between the frame and the wall.

- Bound materials

The most common way to display bound materials is closed and lying horizontally. If a volume is shown open, the object should be open only as much as its binding allows. Common practice is to open volumes at an angle no greater than 135°.[22] There are some types of equipment that help support volumes as they displayed openly: blocks or wedges, which hold a book cover to reduce stain at the book hinge; cradles, which support bound volumes as they lay open without stress to the binding structure; and polyester film strips, which help to secure open leaves. Textblock supports are best used in conjunction with book cradles where the textblock is greater than 1/2 inch, or where the textblock noticeably sags.[23] Regardless of its method of support, however, it is worth noting that any book that is kept open for long periods can cause damage. One should turn an exhibited book's pages every few days in order to protect pages from overexposure to light and spread any strain on the binding structure.

Security

Because exhibited items are often of special interest, they demand a high level of security to reduce the risk of loss from theft or vandalism. Exhibition cases should be securely locked. In addition, cases may be glazed with a material that hinders penetration and that when broken does not risk shards of glass falling on the exhibits.[24] Whenever possible, the exhibition area should be patrolled; a 24-hour security presence is recommended when precious treasures are exhibited.[25] Finally, the exhibition is best protected when equipped with intruder alarms, which can be fitted at entry points to the building and internal areas.

See also

- Arts festival

- Exhibition history

- List of museums

Notes

- Kyoto Triennial

- Mary Todd Glaser, "Protecting Paper and Book Collections During Exhibition," Northeast Document Conservation Center, NEDCC.org Archived August 28, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, (accessed August 9, 2009).

- "NISO.org". Archived from the original on 2015-05-12. Retrieved 2009-08-10.

- National Preservation Office, Guidance for Exhibiting Library and Archive Materials, Preservation Management Series (London: British Library, 2000), 2.

- National Preservation Office, Guidance for Exhibiting Library and Archive Materials, Preservation Management Series (London: British Library, 2000), 2.

- National Information Standards Organization, Environmental Conditions for Exhibiting Library and Archival Materials (Bethesda, MD: NISO Press., 2001), 6.

- Gary Thompson, The Museum Environment, 2nd ed. (London: Butterworths, 1986), 183.

- NISO, 6.

- Edward P. Adcock, IFLA Principles for the Care and Handling of Library Material (Paris: IFLA, 1998), 27.

- Edward P. Adcock, IFLA Principles for the Care and Handling of Library Material (Paris: IFLA, 1998), 27.

- Edward P. Adcock, IFLA Principles for the Care and Handling of Library Material (Paris: IFLA, 1998), 27.

- NISO, 6.

- Edward P. Adcock, IFLA Principles for the Care and Handling of Library Material (Paris: IFLA, 1998), 8.

- Edward P. Adcock, IFLA Principles for the Care and Handling of Library Material (Paris: IFLA, 1998), 6.

- Edward P. Adcock, IFLA Principles for the Care and Handling of Library Material (Paris: IFLA, 1998), 6.

- Nelly Balloffet, and Jenny Hille, Preservation and Conservation for Libraries and Archives (Chicago: ALA, 2005), 37.

- NISO, 10.

- Nelly Balloffet, and Jenny Hille, Preservation and Conservation for Libraries and Archives (Chicago: ALA, 2005), 37.

- Nelly Balloffet, and Jenny Hille, Preservation and Conservation for Libraries and Archives (Chicago: ALA, 2005), 11.

- Glaser, NEDCC.org Archived August 28, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, (accessed August 09, 2009).

- Gail E. Farr, Archives and Manuscripts: Exhibits (Chicago: Society of American Archivists, 1980), 42.

- NISO, 12.

- NPO, 6.

- Nelly Balloffet, and Jenny Hille, Preservation and Conservation for Libraries and Archives (Chicago: ALA, 2005), 154.

- Gail E. Farr, Archives and Manuscripts: Exhibits (Chicago: Society of American Archivists, 1980), 22.

References

- O'Doherty, Brian and McEvilley, Thomas (1999). Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space. University of California Press, Expanded edition. ISBN 0-520-22040-4.

- New York School Abstract Expressionists Artists Choice by Artists, New York School Press, 2000. ISBN 0-9677994-0-6.

- National Information Standards Organization. Environmental Conditions for Exhibiting Library and Archival Materials. Bethesda, MD: NISO Press, 2001.

- National Preservation Office. Guidance for Exhibiting Library and Archive Materials. Preservation Management Series. London: British Library, 2000.

- Francis Haskell, The Ephemeral Museum: Old Master Paintings in the Rise of Art Exhibition, Yale University, 2000.

- Bruce Altshuler, Salon to Biennial: Exhibitions That Made Art History. Volume I: 1863–1959, Phaidon Editors, 2008.

- Bruce Altshuler, Biennials and Beyond: Exhibitions That Made Art History. Volume II: 1962–2002, Phaidon Editors, 2013.

- Where Art Worlds Meet: Multiple Modernities and the Global Salon, ed. Robert Storr, Marsilio, 2005.

- What Makes a Great Exhibition, ed. Paula Marincola, Philadelphia Exhibitions Initiative, 2006.

- Hans Ulrich Obrist, A Brief History of Curating, Zurich-Dijon 2008.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Art exhibitions. |