Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro (/ˈriːoʊ di ʒəˈnɛəroʊ, - deɪ -, - də -/; Portuguese: [ˈʁi.u d(ʒi) ʒɐˈne(j)ɾu] (![]()

Rio de Janeiro Rio | |

|---|---|

| Município do Rio de Janeiro Municipality of Rio de Janeiro | |

From the top, clockwise: panorama of the buildings of the Rio Downtown; statue of Christ the Redeemer on Corcovado; Sugarloaf Mountain with Botafogo's beach; Barra da Tijuca beach with the Pedra da Gávea at background; Museum of Tomorrow in Plaza Mauá with Rio–Niterói Bridge at background and tram of Santa Teresa. | |

Coat of arms | |

| Nickname(s): Cidade Maravilhosa (Marvellous City) Princesa Maravilhosa (Marvellous Princess) Cidade dos Brasileiros (City of Brazilians) | |

Location in the state of Rio de Janeiro | |

Rio de Janeiro Location in Brazil, east South America | |

| Coordinates: 22°54′30″S 43°11′47″W | |

| Country | |

| Region | Southeast |

| State | |

| Historic countries | |

| Founded | 1 March 1565[1] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor-council |

| • Mayor | Marcelo Crivella (PRB) |

| • Vice Mayor | Vacant[note 1] |

| Area | |

| • Municipality | 1,221 km2 (486.5 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 4,539.8 km2 (1,759.6 sq mi) |

| Elevation | from 0 to 1,020 m (from 0 to 3,349 ft) |

| Population (2019)[2] | |

| • Municipality | 6,718,903 |

| • Rank | 2nd |

| • Urban | 11,616,000 |

| • Metro | 12,280,702 (2nd) |

| • Metro density | 2,705.1/km2 (7,006/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Carioca and Guanabarino(a) (by former city-state, obsolete) |

| Time zone | UTC−3 (BRT) |

| Postal Code | 20000-000 |

| Area code(s) | +55 21 |

| Website | prefeitura.rio |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | vi |

| Designated | 2012 (36th session) |

| Reference no. | 1100 |

| State Party | Brazil |

| Latin America and Europe | |

Founded in 1565 by the Portuguese, the city was initially the seat of the Captaincy of Rio de Janeiro, a domain of the Portuguese Empire. Later, in 1763, it became the capital of the State of Brazil, a state of the Portuguese Empire. In 1808, when the Portuguese Royal Court transferred itself from Portugal to Brazil, Rio de Janeiro became the chosen seat of the court of Queen Maria I of Portugal, who subsequently, in 1815, under the leadership of her son, the Prince Regent, and future King João VI of Portugal, raised Brazil to the dignity of a kingdom, within the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil, and Algarves. Rio stayed the capital of the pluricontinental Lusitanian monarchy until 1822, when the War of Brazilian Independence began. This is one of the few instances in history that the capital of a colonising country officially shifted to a city in one of its colonies. Rio de Janeiro subsequently served as the capital of the independent monarchy, the Empire of Brazil, until 1889, and then the capital of a republican Brazil until 1960 when the capital was transferred to Brasília.

Rio de Janeiro has the second largest municipal GDP in the country,[6] and 30th largest in the world in 2008,[7] estimated at about R$343 billion (nearly US$201 billion). It is headquarters to Brazilian oil, mining, and telecommunications companies, including two of the country's major corporations – Petrobras and Vale – and Latin America's largest telemedia conglomerate, Grupo Globo. The home of many universities and institutes, it is the second-largest center of research and development in Brazil, accounting for 17% of national scientific output according to 2005 data.[8] Despite the high perception of crime, the city actually has a lower incidence of crime than most state capitals in Brazil. [9]

Rio de Janeiro is one of the most visited cities in the Southern Hemisphere and is known for its natural settings, Carnival, samba, bossa nova, and balneario beaches[10] such as Barra da Tijuca, Copacabana, Ipanema, and Leblon. In addition to the beaches, some of the most famous landmarks include the giant statue of Christ the Redeemer atop Corcovado mountain, named one of the New Seven Wonders of the World; Sugarloaf Mountain with its cable car; the Sambódromo (Sambadrome), a permanent grandstand-lined parade avenue which is used during Carnival; and Maracanã Stadium, one of the world's largest football stadiums. Rio de Janeiro was the host of the 2016 Summer Olympics and the 2016 Summer Paralympics, making the city the first South American and Portuguese-speaking city to ever host the events, and the third time the Olympics were held in a Southern Hemisphere city.[11] The Maracanã Stadium held the finals of the 1950 and 2014 FIFA World Cups, the 2013 FIFA Confederations Cup, and the XV Pan American Games.

History

Colonial period

Europeans first encountered Guanabara Bay on 1 January 1502 (hence Rio de Janeiro, "January River"), by a Portuguese expedition under explorer Gaspar de Lemos, captain of a ship in Pedro Álvares Cabral's fleet, or under Gonçalo Coelho.[12] Allegedly the Florentine explorer Amerigo Vespucci participated as observer at the invitation of King Manuel I in the same expedition. The region of Rio was inhabited by the Tupi, Puri, Botocudo and Maxakalí peoples.[13]

In 1555, one of the islands of Guanabara Bay, now called Villegagnon Island, was occupied by 500 French colonists under the French admiral Nicolas Durand de Villegaignon. Consequently, Villegagnon built Fort Coligny on the island when attempting to establish the France Antarctique colony.

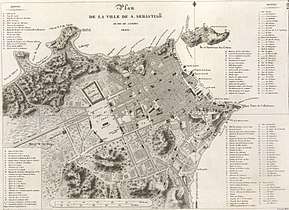

The city of Rio de Janeiro proper was founded by the Portuguese on 1 March 1565 and was named São Sebastião do Rio de Janeiro, in honour of St. Sebastian, the saint who was the namesake and patron of the Portuguese then-monarch Sebastião. Rio de Janeiro was the name of Guanabara Bay. Until early in the 18th century, the city was threatened or invaded by several mostly French pirates and buccaneers, such as Jean-François Duclerc and René Duguay-Trouin.[14]

In the late 17th century, still during the Sugar Era, the Bandeirantes discovered gold and diamonds in the neighbouring captaincy of Minas Gerais, thus Rio de Janeiro became a much more practical port for exporting wealth (gold, precious stones, besides the sugar) than Salvador, Bahia, much farther northeast. On 27 January 1763,[15] the colonial administration in Portuguese America was moved from Salvador to Rio de Janeiro. The city remained primarily a colonial capital until 1808, when the Portuguese royal family and most of the associated Lisbon nobles, fleeing from Napoleon's invasion of Portugal, moved to Rio de Janeiro.

Portuguese court and imperial capital

The kingdom's capital was transferred to the city, which, thus, became the only European capital outside of Europe. As there was no physical space or urban structure to accommodate hundreds of noblemen who arrived suddenly, many inhabitants were simply evicted from their homes.[16] In the first decade, several educational establishments were created, such as the Military Academy, the Royal School of Sciences, Arts and Crafts and the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts, as well as the National Library of Brazil – with the largest collection in Latin America[17] – and The Botanical Garden. The first printed newspaper in Brazil, the Gazeta do Rio de Janeiro, came into circulation during this period.[18] When Brazil was elevated to Kingdom in 1815, it became the capital of the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves until the return of the Portuguese Royal Family to Lisbon in 1821, but remained as capital of the Kingdom of Brazil.[19]

From the colonial period until the first independent era, Rio de Janeiro was a city of slaves. There was a large influx of African slaves to Rio de Janeiro: in 1819, there were 145,000 slaves in the captaincy. In 1840, the number of slaves reached 220,000 people.[20] The Port of Rio de Janeiro was the largest port of slaves in America.[21]

When Prince Pedro proclaimed the independence of Brazil in 1822, he decided to keep Rio de Janeiro as the capital of his new empire while the place was enriched with sugar cane agriculture in the Campos region and, especially, with the new coffee cultivation in the Paraíba Valley.[19] In order to separate the province from the capital of the Empire, the city was converted, in the year of 1834, in Neutral Municipality, passing the province of Rio de Janeiro to have Niterói as capital.[19]

As a political centre of the country, Rio concentrated the political-partisan life of the Empire. It was the main stage of the abolitionist and republican movements in the last half of the 19th century.[19] At that time the number of slaves was drastically reduced and the city was developed, with modern drains, animal trams, train stations crossing the city, gas and electric lighting, telephone and telegraph wiring, water and river plumbing.[19] Rio continued as the capital of Brazil after 1889, when the monarchy was replaced by a republic.

On 6 February 1889 the Bangu Textile Factory was founded, with the name of Industrial Progress Company of Brazil (Companhia Progresso Industrial do Brasil). The factory was officially opened on 8 March 1893, in a complex with varying architectural styles like Italianate, Neo-Gothic and a tower in Mansard Roof style. After the opening in 1893, workers from Great Britain arrived in Bangu to work in the textile factory. The old farms became worker villages with red bricks houses, and a neo-gothic church was created, which still exists as the Saint Sebastian and Saint Cecilia Parish Church. Street cinemas and cultural buildings also appeared. In May 1894, Thomas Donohoe, a British worker from Busby, Scotland, arrived in Bangu.[22]

Donohoe was horrified to discover that there was absolutely no knowledge of football among Brazilians. So he wrote to his wife, Elizabeth, asking her to bring a football when she joined him. And shortly after her arrival, in September 1894, the first football match in Brazil took place in the field beside the textile factory. It was a five-a-side match between British workers, and took place six months before the first game organized by Charles Miller in São Paulo. However, the Bangu Football Club was not formally created until 1904.[23]

Republican period

At the time Brazil's Old Republic was established, the city lacked urban planning and sanitation, which helped spread several diseases, such as yellow fever, dysentery, variola, tuberculosis and even black death. Pereira Passos, who was named mayor in 1902, imposed reforms to modernize the city, demolishing the cortiços where most of the poor population lived. These people, mostly descendants of slaves, then moved to live in the city's hills, creating the first favelas.[24] Inspired by the city of Paris, Passos built the Municipal Theatre, the National Museum of Fine Arts and the National Library in the city's center; brought electric power to Rio and created larger avenues to adapt the city to automobiles.[25] Passos also named Dr. Oswaldo Cruz as Director General of Public Health. Cruz's plans to clean the city of diseases included compulsory vaccination of the entire population and forced entry into houses to kill mosquitos and rats. The people of city rebelled against Cruz's policy, in what would be known as the Vaccine Revolt.[26]

In 1910, Rio saw the Revolt of the Lash, where Afro-Brazilian crew members in the Brazilian Navy mutinied against the heavy use of corporal punishment, which was similar to the punishment slaves received. The mutineers took control of the battleship Minas Geraes and threatened to fire on the city. Another military revolt occurred in 1922, the 18 of the Copacabana Fort revolt, a march against the Old Republic's coronelism and café com leite politics. This revolt marked the beginning of Tenentism, a movement that resulted in the Brazilian Revolution of 1930 that started the Vargas Era.

Until the early years of the 20th century, the city was largely limited to the neighbourhood now known as the historic city centre (see below), on the mouth of Guanabara Bay. The city's centre of gravity began to shift south and west to the so-called Zona Sul (South Zone) in the early part of the 20th century, when the first tunnel was built under the mountains between Botafogo and the neighbourhood that is now known as Copacabana. Expansion of the city to the north and south was facilitated by the consolidation and electrification of Rio's streetcar transit system after 1905.[27] Botafogo's natural environment, combined with the fame of the Copacabana Palace Hotel, the luxury hotel of the Americas in the 1930s, helped Rio to gain the reputation it still holds today as a beach party town. This reputation has been somewhat tarnished in recent years by favela violence resulting from the narcotics trade and militias.[28]

Plans for moving the nation's capital city from Rio de Janeiro to the centre of Brazil had been occasionally discussed, and when Juscelino Kubitschek was elected president in 1955, it was partially on the strength of promises to build a new capital.[29] Though many thought that it was just campaign rhetoric, Kubitschek managed to have Brasília and a new Federal District built, at great cost, by 1960. On 21 April of that year, the capital of Brazil was officially moved to Brasília. The territory of the former Federal District became its own state, Guanabara, after the bay that borders it to the east, encompassing just the city of Rio de Janeiro. After the 1964 coup d'état that installed a military dictatorship, the city-state was the only state left in Brazil to oppose the military. Then, in 1975, a presidential decree known as "The Fusion" removed the city's federative status and merged it with the State of Rio de Janeiro, with the city of Rio de Janeiro replacing Niterói as the state's capital, and establishing the Rio de Janeiro Metropolitan Region.[30]

In 1992, Rio hosted the Earth Summit, a United Nations conference to fight environmental degradation. Twenty years later, in 2012, the city hosted another conference on sustainable development, named United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development. The city hosted the World Youth Day in 2013, the second World Youth Day in South America and first in Brazil. In the sports field, Rio de Janeiro was the host of the 2007 Pan American Games and the 2014 FIFA World Cup Final. On 2 October 2009, the International Olympic Committee announced that Rio de Janeiro would host the 2016 Olympic Games and the 2016 Paralympic Games, beating competitors Chicago, Tokyo, and Madrid. The city became the first South American city to host the event and the second Latin American city (after Mexico City in 1968) to host the Games.

Geography

.jpg)

Rio de Janeiro is on the far western part of a strip of Brazil's Atlantic coast (between a strait east to Ilha Grande, on the Costa Verde, and the Cabo Frio), close to the Tropic of Capricorn, where the shoreline is oriented east–west. Facing largely south, the city was founded on an inlet of this stretch of the coast, Guanabara Bay (Baía de Guanabara), and its entrance is marked by a point of land called Sugar Loaf (Pão de Açúcar) – a "calling card" of the city.[31]

The Centre (Centro), the core of Rio, lies on the plains of the western shore of Guanabara Bay. The greater portion of the city, commonly referred to as the North Zone (Zona Norte, Rio de Janeiro), extends to the northwest on plains composed of marine and continental sediments and on hills and several rocky mountains. The South Zone (Zona Sul) of the city, reaching the beaches fringing the open sea, is cut off from the Centre and from the North Zone by coastal mountains. These mountains and hills are offshoots of the Serra do Mar to the northwest, the ancient gneiss-granite mountain chain that forms the southern slopes of the Brazilian Highlands. The large West Zone (Zona Oeste), long cut off by the mountainous terrain, had been made more easily accessible to those on the South Zone by new roads and tunnels by the end of the 20th century.[32]

The population of the city of Rio de Janeiro, occupying an area of 1,182.3 square kilometres (456.5 sq mi),[33] is about 6,000,000.[34] The population of the greater metropolitan area is estimated at 11–13.5 million. Residents of the city are known as cariocas. The official song of Rio is "Cidade Maravilhosa", by composer André Filho.

Parks

The city has parks and ecological reserves such as the Tijuca National Park, the world's first urban forest and UNESCO Environmental Heritage and Biosphere Reserve; Pedra Branca State Park, which houses the highest point of Rio de Janeiro, the peak of Pedra Branca; the Quinta da Boa Vista complex; the Botanical Garden;[35] Rio's Zoo; Parque Lage; and the Passeio Público, the first public park in the Americas.[36] In addition the Flamengo Park is the largest landfill in the city, extending from the center to the south zone, and containing museums and monuments, in addition to much vegetation.

Environment

Due to the high concentration of industries in the metropolitan region, the city has faced serious problems of environmental pollution. The Guanabara Bay has lost mangrove areas and suffers from residues from domestic and industrial sewage, oils and heavy metals. Although its waters renew when they reach the sea, the bay is the final receiver of all the tributaries generated along its banks and in the basins of the many rivers and streams that flow into it. The levels of particulate matter in the air are twice as high as that recommended by the World Health Organization, in part because of the large numbers of vehicles in circulation.[37]

The waters of Sepetiba Bay are slowly following the path traced by Guanabara Bay, with sewage generated by a population of the order of 1.29 million inhabitants being released without treatment in streams or rivers. With regard to industrial pollution, highly toxic wastes, with high concentrations of heavy metals – mainly zinc and cadmium – have been dumped over the years by factories in the industrial districts of Santa Cruz, Itaguaí and Nova Iguaçu, constructed under the supervision of State policies.[38]

The Marapendi lagoon and the Rodrigo de Freitas Lagoon have suffered with the leniency of the authorities and the growth in the number of apartment buildings close by. The illegal discharge of sewage and the consequent deaths of algae diminished the oxygenation of the waters, causing fish mortality.[39][40]

There are, on the other hand, signs of decontamination in the lagoon made through a public-private partnership established in 2008 to ensure that the lagoon waters will eventually be suitable for bathing. The decontamination actions involve the transfer of sludge to large craters present in the lagoon itself, and the creation of a new direct and underground connection with the sea, which will contribute to increase the daily water exchange between the two environments. However, during the Olympics the lagoon hosted the rowing competitions and there were numerous concerns about potential infection resulting from human sewage.[41]

Climate

Rio has a tropical savanna climate (Aw) that closely borders a tropical monsoon climate (Am) according to the Köppen climate classification, and is often characterized by long periods of heavy rain between December and March.[42] The city experiences hot, humid summers, and warm, sunny winters. In inland areas of the city, temperatures above 40 °C (104 °F) are common during the summer, though rarely for long periods, while maximum temperatures above 27 °C (81 °F) can occur on a monthly basis.

Along the coast, the breeze, blowing onshore and offshore, moderates the temperature. Because of its geographic situation, the city is often reached by cold fronts advancing from Antarctica, especially during autumn and winter, causing frequent weather changes. In summer there can be strong rains, which have, on some occasions, provoked catastrophic floods and landslides. The mountainous areas register greater rainfall since they constitute a barrier to the humid wind that comes from the Atlantic.[43] The city has had rare frosts in the past. Some areas within Rio de Janeiro state occasionally have falls of snow grains and ice pellets (popularly called granizo) and hail. [44][45][46]

Drought is very rare, albeit bound to happen occasionally given the city's strongly seasonal tropical climate. The Brazilian drought of 2014–2015, most severe in the Southeast Region and the worst in decades, affected the entire metropolitan region's water supply (a diversion from the Paraíba do Sul River to the Guandu River is a major source for the state's most populous mesoregion). There were plans to divert the Paraíba do Sul to the Sistema Cantareira (Cantareira system) during the water crisis of 2014 in order to help the critically drought-stricken Greater São Paulo area. However, availability of sufficient rainfall to supply tap water to both metropolitan areas in the future is merely speculative.[47][48][49]

Roughly in the same suburbs (Nova Iguaçu and surrounding areas, including parts of Campo Grande and Bangu) that correspond to the location of the March 2012, February–March 2013 and January 2015 pseudo-hail (granizo) falls, there was a tornado-like phenomenon in January 2011, for the first time in the region's recorded history, causing structural damage and long-lasting blackouts, but no fatalities.[50][51] The World Meteorological Organization has advised that Brazil, especially its southeastern region, must be prepared for increasingly severe weather occurrences in the near future, since events such as the catastrophic January 2011 Rio de Janeiro floods and mudslides are not an isolated phenomenon. In early May 2013, winds registering above 90 km/h (56 mph) caused blackouts in 15 neighborhoods of the city and three surrounding municipalities, and killed one person.[52] Rio saw similarly high winds (about 100 km/h (62 mph)) in January 2015.[53] The average annual minimum temperature is 21 °C (70 °F),[54] the average annual maximum temperature is 27 °C (81 °F),[55] and the average annual temperature is 24 °C (75 °F).[56] The average yearly precipitation is 1,069 mm (42.1 in).[57]

Temperature also varies according to elevation, distance from the coast, and type of vegetation or land use. During the winter, cold fronts and dawn/morning sea breezes bring mild temperatures; cold fronts, the Intertropical Convergence Zone (in the form of winds from the Amazon Forest), the strongest sea-borne winds (often from an extratropical cyclone) and summer evapotranspiration bring showers or storms. Thus the monsoon-like climate has dry and mild winters and springs, and very wet and warm summers and autumns. As a result, temperatures over 40 °C (104 °F), that may happen about year-round but are much more common during the summer, often mean the actual temperature feeling is over 50 °C (122 °F), when there is little wind and the relative humidity percentage is high.[58][59][60][61]

Rio de Janeiro is second only to Cuiabá as the hottest Brazilian state capital outside Northern and Northeastern Brazil; temperatures below 14 °C (57 °F) occur yearly, while those lower than 11 °C (52 °F) happen less often. The phrase, fazer frio ("making cold", i.e. "the weather is getting cold"), usually refers to temperatures going below 21 °C (70 °F), which is possible year-round and is commonplace in mid-to-late autumn, winter and early spring nights.

Between 1961 and 1990, at the INMET (Brazilian National Institute of Meteorology) conventional station in the neighborhood of Saúde, the lowest temperature recorded was 10.1 °C (50.2 °F) in October 1977,[62] and the highest temperature recorded was 39 °C (102.2 °F) in December 1963.[63] The highest accumulated rainfall in 24 hours was 167.4 mm (6.6 in) in January 1962.[64] However, the absolute minimum temperature ever recorded at the INMET Jacarepaguá station was 3.8 °C (38.8 °F) in July 1974,[62] while the absolute maximum was 43.2 °C (110 °F) on 26 December 2012[65] in the neighborhood of the Santa Cruz station. The highest accumulated rainfall in 24 hours, 186.2 mm (7.3 in), was recorded at the Santa Teresa station in April 1967.[64] The lowest temperature ever registered in the 21st century was 8.1 °C (46.6 °F) in Vila Militar, July 2011.[66]

| Climate data for Rio de Janeiro (station of Saúde, 1961—1990) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 40.9 (105.6) |

41.8 (107.2) |

41.0 (105.8) |

39.3 (102.7) |

36.3 (97.3) |

35.9 (96.6) |

34.9 (94.8) |

38.9 (102.0) |

40.6 (105.1) |

42.8 (109.0) |

40.5 (104.9) |

43.2 (109.8) |

43.2 (109.8) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 30.2 (86.4) |

30.2 (86.4) |

29.4 (84.9) |

27.8 (82.0) |

26.4 (79.5) |

25.2 (77.4) |

25.0 (77.0) |

25.5 (77.9) |

25.4 (77.7) |

26.0 (78.8) |

27.4 (81.3) |

28.6 (83.5) |

27.3 (81.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 26.3 (79.3) |

26.6 (79.9) |

26.0 (78.8) |

24.4 (75.9) |

22.8 (73.0) |

21.8 (71.2) |

21.3 (70.3) |

21.8 (71.2) |

22.2 (72.0) |

22.9 (73.2) |

24.0 (75.2) |

25.3 (77.5) |

23.8 (74.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 23.3 (73.9) |

23.5 (74.3) |

23.3 (73.9) |

21.9 (71.4) |

20.4 (68.7) |

18.7 (65.7) |

18.4 (65.1) |

18.9 (66.0) |

19.2 (66.6) |

20.2 (68.4) |

21.4 (70.5) |

22.4 (72.3) |

21.0 (69.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 17.7 (63.9) |

18.9 (66.0) |

18.6 (65.5) |

16.2 (61.2) |

11.1 (52.0) |

11.6 (52.9) |

12.2 (54.0) |

10.6 (51.1) |

10.2 (50.4) |

10.1 (50.2) |

15.1 (59.2) |

17.1 (62.8) |

10.1 (50.2) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 137.1 (5.40) |

130.4 (5.13) |

135.8 (5.35) |

94.9 (3.74) |

69.8 (2.75) |

42.7 (1.68) |

41.9 (1.65) |

44.5 (1.75) |

53.6 (2.11) |

86.5 (3.41) |

97.8 (3.85) |

134.2 (5.28) |

1,069.4 (42.10) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1 mm) | 11 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 93 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 79 | 79 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 79 | 77 | 77 | 79 | 80 | 79 | 80 | 79.1 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 211.9 | 201.3 | 206.4 | 181.0 | 186.3 | 175.1 | 188.6 | 184.8 | 146.2 | 152.1 | 168.5 | 179.6 | 2,181.8 |

| Source: Brazilian National Institute of Meteorology (INMET).[54][55][56][57][62][63][67][68][69] | |||||||||||||

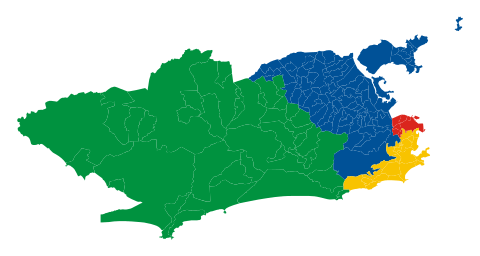

City districts

|

West Zone |

North Zone |

South Zone |

Central Zone |

The city is commonly divided into the historic center (Centro); the tourist-friendly wealthier South Zone (Zona Sul); the residential less wealthy North Zone (Zona Norte); peripheries in the West Zone (Zona Oeste), among them Santa Cruz, Campo Grande and the wealthy newer Barra da Tijuca district.

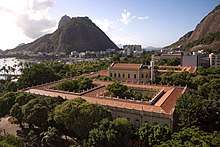

Central Zone

Centro or Downtown is the historic core of the city, as well as its financial centre. Sites of interest include the Paço Imperial, built during colonial times to serve as a residence for the Portuguese governors of Brazil; many historic churches, such as the Candelária Church (the former cathedral), São Jose, Santa Lucia, Nossa Senhora do Carmo, Santa Rita, São Francisco de Paula, and the monasteries of Santo Antônio and São Bento. The Centro also houses the modern concrete Rio de Janeiro Cathedral. Around the Cinelândia square, there are several landmarks of the Belle Époque of Rio, such as the Municipal Theatre and the National Library building.

Among its several museums, the Museu Nacional de Belas Artes (National Museum of Fine Arts) and the Museu Histórico Nacional (National Historical Museum) are the most important. Other important historical attractions in central Rio include its Passeio Público, an 18th-century public garden. Major streets include Avenida Rio Branco and Avenida Vargas, both constructed, in 1906 and 1942 respectively, by destroying large swaths of the colonial city. A number of colonial streets, such as Rua do Ouvidor and Uruguaiana, have long been pedestrian spaces, and the popular Saara shopping district has been pedestrianized more recently. Also located in the center is the traditional neighbourhood called Lapa, an important bohemian area frequented by both townspeople and tourists.

South Zone

The South Zone of Rio de Janeiro (Zona Sul) is composed of several districts, among which are São Conrado, Leblon, Ipanema, Arpoador, Copacabana, and Leme, which compose Rio's famous Atlantic beach coastline. Other districts in the South Zone are Glória, Catete, Flamengo, Botafogo, and Urca, which border Guanabara Bay, and Santa Teresa, Cosme Velho, Laranjeiras, Humaitá, Lagoa, Jardim Botânico, and Gávea. It is the wealthiest part of the city and the best known overseas; the neighborhoods of Leblon and Ipanema, in particular, have the most expensive real estate in all of South America.

The neighbourhood of Copacabana beach hosts one of the world's most spectacular New Year's Eve parties ("Reveillon"), as more than two million revelers crowd onto the sands to watch the fireworks display. From 2001, the fireworks have been launched from boats, to improve the safety of the event.[70]

To the north of Leme, and at the entrance to Guanabara Bay, is the district of Urca and the Sugarloaf Mountain ('Pão de Açúcar'), whose name describes the famous mountain rising out of the sea. The summit can be reached via a two-stage cable car trip from Praia Vermelha, with the intermediate stop on Morro da Urca. It offers views of the city second only to Corcovado mountain. Hang gliding is a popular activity on the Pedra Bonita (literally, "Beautiful Rock"). After a short flight, gliders land on the Praia do Pepino (Pepino, or "cucumber", Beach) in São Conrado.

Since 1961, the Tijuca National Park (Parque Nacional da Tijuca), the largest city-surrounded urban forest and the second largest urban forest in the world, has been a National Park. The largest urban forest in the world is the Floresta da Pedra Branca (White Rock Forest), which is located in the West Zone of Rio de Janeiro.[71]

The Pontifical Catholic University of Rio (Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro or PUC-Rio), Brazil's top private university, is located at the edge of the forest, in the Gávea district. The 1984 film Blame It on Rio was filmed nearby, with the rental house used by the story's characters sitting at the edge of the forest on a mountain overlooking the famous beaches. In 2012, CNN elected Ipanema the best city beach in the world.[72]

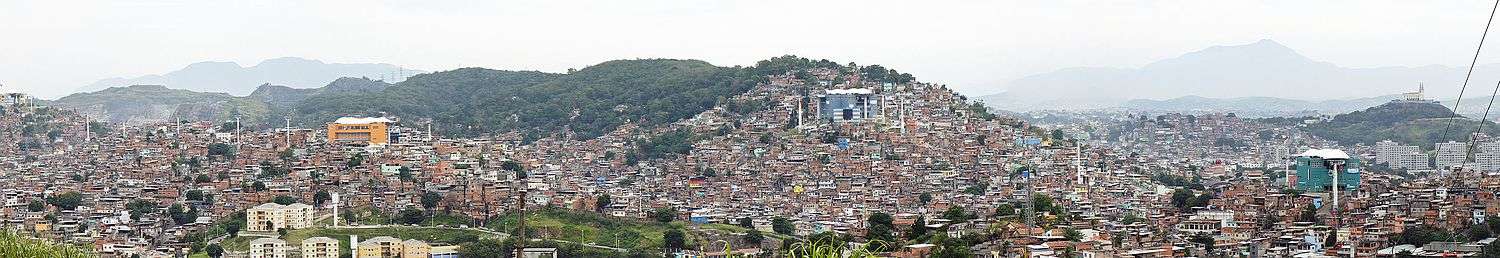

North Zone

The North Zone (Zona Norte) begins at Grande Tijuca (the middle class residential and commercial bairro of Tijuca), just west of the city center, and sprawls for miles inland until Baixada Fluminense and the city's Northwest.

This region is home to the Maracanã stadium (located in Grande Tijuca), once the world's highest capacity football venue, able to hold nearly 199,000 people, as it did for the World Cup final of 1950. More recently its capacity has been reduced to conform with modern safety regulations and the stadium has introduced seating for all fans. Currently undergoing reconstruction, it has now the capacity for 90,000; it will eventually hold around 80,000 people. Maracanã was the site for the Opening and Closing Ceremonies and football competition of the 2007 Pan American Games; hosted the final match of the 2014 FIFA World Cup, the Opening and Closing Ceremonies and the football matches of the 2016 Summer Olympics.

Besides Maracanã, the North Zone of Rio also has other tourist and historical attractions, such "Nossa Senhora da Penha de França Church", the Christ the Redeemer (statue) with its stairway built into the rock bed, 'Manguinhos', the home of Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, a centenarian biomedical research institution with a main building fashioned like a Moorish palace, and the Quinta da Boa Vista, the park where the historic Imperial Palace is located. Nowadays, the palace hosts the National Museum, specialising in Natural History, Archaeology, and Ethnology. The International Airport of Rio de Janeiro (Galeão – Antônio Carlos Jobim International Airport, named after the famous Brazilian musician Antônio Carlos Jobim), the main campus of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro at the Fundão Island, and the State University of Rio de Janeiro, in Maracanã, are also located in the Northern part of Rio.

This region is also home to most of the samba schools of Rio de Janeiro such as Mangueira, Salgueiro, Império Serrano, Unidos da Tijuca, Imperatriz Leopoldinense, among others. Some of the main neighbourhoods of Rio's North Zone are Alto da Boa Vista which shares the Tijuca Rainforest with the South and Southwest Zones; Tijuca, Vila Isabel, Méier, São Cristovão, Madureira, Penha, Manguinhos, Fundão, Olaria among others. Many of Rio de Janeiro's roughly 1000 slums, or favelas, are located in the North Zone.[73] The favelas resemble the slums of Paris, New York or other major cities in the 19th and early 20th centuries in the United States and Europe, or similar neighborhoods in present underdeveloped countries.

West Zone

West Zone (Zona Oeste) of Rio de Janeiro is a vaguely defined area that covers some 50% of the city's entire area, including Barra da Tijuca and Recreio dos Bandeirantes neighborhoods. The West Side of Rio has many historic sites because of the old "Royal Road of Santa Cruz" that crossed the territory in the regions of Realengo, Bangu, and Campo Grande, finishing at the Royal Palace of Santa Cruz in the Santa Cruz region. The highest peak of the city of Rio de Janeiro is the Pedra Branca Peak (Pico da Pedra Branca) inside the Pedra Branca State Park. It has an altitude of 1024m. The Pedra Branca State Park (Parque Estadual da Pedra Branca)[74] is the biggest urban state park in the world comprising 17 neighborhoods in the west side, being a "giant lung" in the city with trails,[75] waterfalls and historic constructions like an old aqueduct in the Colônia Juliano Moreira[76] in the neighborhood of Taquara and a dam in Camorim. The park has three principal entrances: the main one is in Taquara called Pau da Fome Core, another entrance is the Piraquara Core in Realengo and the last one is the Camorim Core, considered the cultural heritage of the city.

Santa Cruz and Campo Grande Region have exhibited economic growth, mainly in the Campo Grande neighborhood. Industrial enterprises are being built in lower and lower middle class residential Santa Cruz, one of the largest and most populous of Rio de Janeiro's neighbourhoods, most notably Ternium Brasil, a new steel mill with its own private docks on Sepetiba Bay, which is planned to be South America's largest steel works.[77] A tunnel called Túnel da Grota Funda, opened in 2012, creating a public transit facility between Barra da Tijuca and Santa Cruz, lessening travel time to the region from other areas of Rio de Janeiro.[78]

Barra da Tijuca region

This is an elite area of the West Zone of the city of Rio de Janeiro. It includes Barra da Tijuca, Recreio dos Bandeirantes, Vargem Grande, Vargem Pequena, Grumari, Itanhangá, Camorim and Joá. Westwards from the older zones of Rio, Barra da Tijuca is a flat complex of barrier islands of formerly undeveloped coastal land, which constantly experiences new constructions and developments. It remains an area of accelerated growth, attracting some of the richer sectors of the population as well as luxury companies. High rise flats and sprawling shopping centers give the area a far more modern feel than the crowded city centre.

The urban planning of the area, completed in the late 1960s, mixes zones of single-family houses with residential skyscrapers. The beaches of Barra da Tijuca are also popular with the residents from other parts of the city. One of the most famous hills in the city is the 842-metre-high (2,762-foot) Pedra da Gávea (Crow's nest Rock) bordering the South Zone. On the top of its summit is a huge rock formation (some, such as Erich von Däniken in his 1973 book, In Search of Ancient Gods, claim it to be a sculpture) resembling a sphinx-like, bearded head that is visible for many kilometres around.

Demographics

According to the 2010 IBGE Census, there were 5,940,224 people residing in the city of Rio de Janeiro.[79] The census revealed the following numbers: 3,239,888 White people (51.2%), 2,318,675 Pardo (multiracial) people (36.5%), 708,148 Black people (11.5%), 45,913 Asian people (0.7%), 5,981 Amerindian people (0.1%).[80] The population of Rio de Janeiro was 53.2% female and 46.8% male.[80]

In 2010, the city of Rio de Janeiro was the 2nd most populous city in Brazil, after São Paulo.[81]

Different ethnic groups contributed to the formation of the population of Rio de Janeiro. Before European colonization, there were at least seven different indigenous peoples speaking 20 languages in the region. A part of them joined the Portuguese and the other the French. Those who joined the French were then exterminated by the Portuguese, while the other part was assimilated.[82]

Rio de Janeiro is home to the largest Portuguese population outside of Lisbon in Portugal.[83] After independence from Portugal, Rio de Janeiro became a destination for hundreds of thousands of immigrants from Portugal, mainly in the early 20th century. The immigrants were mostly poor peasants who subsequently found prosperity in Rio as city workers and small traders.[84] The Portuguese cultural influence is still seen in many parts of the city (and many other parts of the state of Rio de Janeiro), including architecture and language. Most Brazilians with some cultural contact with Rio know how to easily differentiate between the local dialect, fluminense, and other Brazilian dialects.

.jpg)

People of Portuguese ancestry predominate in most of the state. The Brazilian census of 1920 showed that 39.7% of the Portuguese who lived in Brazil lived in Rio de Janeiro. Including all of the Rio de Janeiro, the proportion raised to 46.3% of the Portuguese who lived in Brazil. The numerical presence of the Portuguese was extremely high, accounting for 72% of the foreigners who lived in the capital. Portuguese born people accounted for 20.4% of the population of Rio, and those with a Portuguese father or a Portuguese mother accounted for 30.8%. In other words, native born Portuguese and their children accounted for 51.2% of the inhabitants of Rio, or a total of 267,664 people in 1890.[86]

| Group | Population | Percentage[87] |

|---|---|---|

| Portuguese immigrants | 106,461 | 20.4% |

| Brazilians with at least one Portuguese parent | 161,203 | 30.8% |

| Portuguese immigrants and their descendants | 267,664 | 51.2% |

The black community was formed by residents whose ancestors had been brought as slaves, mostly from Angola and Mozambique, as well by people of Angolan, Mozambican and West African descent who moved to Rio from other parts of Brazil. The samba (from Bahia with Angolan influence) and the famous local version of the carnival (from Europe) first appeared under the influence of the black community in the city.

Today, nearly half of the city's population is by phenotype perceptibly black or part black.[88] A large majority has some recent sub-Saharan ancestor. White in Brazil is defined more by having a European-looking phenotype rather than ancestry, and two full siblings can be of different "racial" categories[89] in a skin color and phenotype continuum from pálido (branco) or fair-skinned, through branco moreno or swarthy Caucasian, mestiço claro or lighter skinned multiracial, pardo (mixed race) to negro or black. Pardo, for example, in popular usage includes those who are caboclos (mestizos), mulatos (mulattoes), cafuzos (zambos), juçaras (archaic term for tri-racials) and westernized Amerindians (which are called caboclos as well), being more of a skin color rather than a racial group in particular.

As a result of the influx of immigrants to Brazil from the late 19th to the early 20th century, also found in Rio de Janeiro and its metropolitan area are communities of Levantine Arabs who are mostly Christian or Irreligious, Spaniards, Italians, Germans, Japanese,[90] Jews, and people from other parts of Brazil. The main waves of internal migration came from people of African, mixed or older Portuguese (as descendants of early settlers) descent from Minas Gerais and people of Eastern European, Swiss, Italian, German, Portuguese and older Portuguese-Brazilian heritage from Espírito Santo in the early and mid-20th century, together with people with origins in Northeastern Brazil, in the mid-to-late and late 20th century, as well some in the early 21st century (the latter more directed to peripheries than the city's core).

| Genomic ancestry of non-related individuals in Rio de Janeiro[91] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race or skin color | Number of individuals | Amerindian | African | European |

| White | 107 | 6.7% | 6.9% | 86.4% |

| Pardo (Mixed race) | 119 | 8.3% | 23.6% | 68.1% |

| Black | 109 | 7.3% | 50.9% | 41.8% |

According to an autosomal DNA study from 2009, conducted on a school in the poor suburb of Rio de Janeiro, the "pardos" there were found to be on average about 80% European, and the "whites" (who thought of themselves as "very mixed") were found to carry very little Amerindian and/or African admixtures. The results of the tests of genomic ancestry are quite different from the self made estimates of European ancestry. In general, the test results showed that European ancestry is far more important than the students thought it would be. The "pardos" for example thought of themselves as ⅓ European, ⅓ African and ⅓ Amerindian before the tests, and yet their ancestry on average reached 80% European.[92][93] Other studies showed similar results[91][94]

| Self-reported ancestry of people from Rio de Janeiro, by race or skin color (2000 survey)[95] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ancestry | White | Pardo | Black |

| European only | 48% | 6% | — |

| African only | — | 12% | 25% |

| Amerindian only | — | 2% | — |

| African and European | 23% | 34% | 31% |

| Amerindian and European | 14% | 6% | — |

| African and Amerindian | — | 4% | 9% |

| African, Amerindian and European | 15% | 36% | 35% |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% |

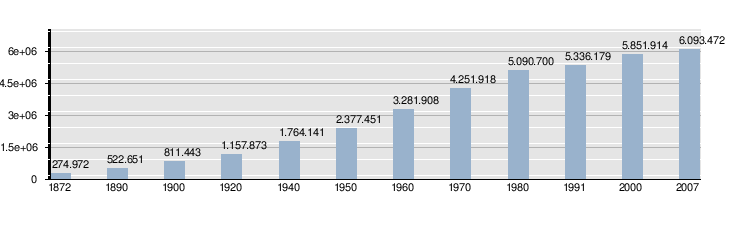

Population growth

Rio de Janeiro is the second largest city in Brazil (after São Paulo) and has a rapidly expanding population and rapidly growing area due to rapid urbanization.

- Changing demographics the city of Rio de Janeiro[96]

Religion

The Rio de Janeiro metropolitan area, according to 2009 research from Fundação Getúlio Vargas (known as Novo Mapa das Religiões), is mostly Catholic (51.1%). Rio de Janeiro city also ranks fifth among Brazilian state capital cities in the percentage of its population that is irreligious (13.3%), barely changing since 2000 (the first-ranked, Boa Vista, has 21.2% irreligious).[97][98] It is also the Brazilian state capital with the greatest percentage of Spiritists (now about 4–5%), and with substantial numbers in Afro-Brazilian religions and Eastern religions.

| Religion | Percentage | Number |

| Catholic | 51.1% | 3,229,192 |

| Protestant | 23.4% | 1,477,021 |

| Irreligious | 13.6% | 858,704 |

| Spiritist | 5.9% | 372,851 |

| Umbanda and Candomblé | 1.3% | 72,946 |

| Jewish | 0.3% | 21,800 |

| Source: IBGE 2010.[99] | ||

Social issues

There are significant disparities between the rich and the poor in Rio de Janeiro, and different socioeconomic groups are largely segregated into different neighborhoods.[100] Although the city clearly ranks among the world's major metropolises, large numbers live in slums known as favelas, where 95% of the population are poor, compared to 40% in the general population.[101]

There have been a number of government initiatives to counter this problem, from the removal of the population from favelas to housing projects such as Cidade de Deus to the more recent approach of improving conditions in the favelas and bringing them up to par with the rest of the city, as was the focus of the "Favela Bairro" program and deployment of Pacifying Police Units.

Rio has more people living in slums than any other city in Brazil, according to the 2010 Census.[102] More than 1,500,000 people live in its 763 favelas, 22% of Rio's total population. São Paulo, the largest city in Brazil, has more favelas (1,020) in sheer numbers, but proportionally has fewer people living in favelas than Rio.

Rio also has a large proportion of state-sanctioned violence, with about 20% of all killings committed by state security.[103] In 2019, police killed an average of five people each day in the state of Rio de Janeiro, with a total of 1,810 killed in the year. This was more police killings than any year since official records started in 1998.[104]

Economy

Rio de Janeiro has the second largest GDP of any city in Brazil, surpassed only by São Paulo. According to the IBGE, it was approximately US$201 billion in 2008, equivalent to 5.1% of the national total. Taking into consideration the network of influence exerted by the urban metropolis (which covers 11.3% of the population), this share in GDP rises to 14.4%, according to a study released in October 2008 by the IBGE.[106]

Greater Rio de Janeiro, as perceived by the IBGE, has a GDP of US$187 billion, constituting the second largest hub of national wealth. Per capita GDP is US$11,786.[107] It concentrates 68% of the state's economic strength and 7.9% of all goods and services produced in the country.[108] The services sector comprises the largest portion of GDP (65.5%), followed by commerce (23.4%), industrial activities (11.1%) and agriculture (0.1%).[109][110]

Benefiting from the federal capital position it had for a long period (1763–1960), the city became a dynamic administrative, financial, commercial and cultural center. Rio de Janeiro became an attractive place for companies to locate when it was the capital of Brazil, as important sectors of society and of the government were present in the city, even when their factories were located in other cities or states. The city was chosen as headquarters for state-owned companies such as Petrobras, Eletrobras, Caixa Econômica Federal, National Economic and Social Development Bank and Vale (which was privatized in the 1990s). The Rio de Janeiro Stock Exchange (BVRJ), which currently trades only government securities, was the first stock exchange founded in Brazil in 1845. Despite the transfer of the capital to Brasília in 1960, many of these headquarters remained within the Rio metropolitan area.

The off-shore oil exploration in the Campos Basin began in 1968 and became the main site for oil production of Brazil. This caused many oil and gas companies to be based in Rio de Janeiro, such as the Brazilian branches of Shell, EBX and Esso. For many years Rio was the second largest industrial hub of Brazil,[111] with oil refineries, shipbuilding industries, steel, metallurgy, petrochemicals, cement, pharmaceutical, textile, processed foods and furniture industries.

Major international pharmaceutical companies have their Brazilian headquarters in Rio such as: Merck, Roche, Arrow, Darrow, Baxter, Mayne, and Mappel. A newer electronics and computer sector has been added to the more-established industries. Construction, also an important activity, provides a significant source of employment for large numbers of unskilled workers and is buoyed by the number of seasonal residents who build second homes in the Greater Rio de Janeiro area.

Rio is an important financial centre, second only to São Paulo in volume of business. Its securities market, although declining in significance relative to São Paulo, is still of major importance. Recent decades have seen a sharp transformation in its economic profile, which is becoming more and more one of a major national hub of services and businesses.[112] The city is the headquarters of large telecom companies, such as Intelig, Oi and Embratel. Major Brazilian entertainment and media organizations are based in Rio de Janeiro like Organizações Globo and also some of Brazil's major newspapers: Jornal do Brasil, O Dia, and Business Rio.

Tourism and entertainment are other key aspects of the city's economic life. The city is the nation's top tourist attraction for both Brazilians and foreigners.[113]

To attract industry, the state government has designated certain areas on the outskirts of the city as industrial districts where infrastructure is provided and land sales are made under special conditions. Oil and natural gas from fields off the northern coast of Rio de Janeiro state are a major asset used for developing manufacturing activities in Rio's metropolitan area, enabling it to compete with other major cities for new investment in industry.[114]

Owing to the proximity of Rio's port facilities, many of Brazil's export-import companies are headquartered in the city. In Greater Rio, which has one of the highest per capita incomes in Brazil, retail trade is substantial. Many of the most important retail stores are located in the Centre, but others are scattered throughout the commercial areas of the other districts, where shopping centres, supermarkets, and other retail businesses handle a large volume of consumer trade.[115]

Rio de Janeiro is (as of 2014) the second largest exporting municipality in Brazil. Annually, Rio exported a total of $7.49B (USD) worth of goods.[116] The top three goods exported by the municipality were crude petroleum (40%), semi finished iron product (16%), and semi finished steel products (11%).[117] Material categories of mineral products (42%) and metals (29%) make up 71% of all exports from Rio.[118]

Compared to other cities, Rio de Janeiro's economy is the 2nd largest in Brazil, behind São Paulo, and the 30th largest in the world with a GDP of R$ 201,9 billion in 2010. The per capita income for the city was R$22,903 in 2007 (around US$14,630).[119] Largely because of the strength of Brazil's currency at the time, Mercer's city rankings of cost of living for expatriate employees, reported that Rio de Janeiro ranked 12th among the most expensive cities in the world in 2011, up from the 29th position in 2010, just behind São Paulo (ranked 10th), and ahead of London, Paris, Milan, and New York City.[120][121] Rio also had the most expensive hotel rates in Brazil, and the daily rate of its five star hotels were the second most expensive in the world after only New York City.[122]

Tourism

Rio de Janeiro is Brazil's primary tourist attraction and resort. It receives the most visitors per year of any city in South America with 2.82 million international tourists a year.[123]

The city boasts world-class hotels, like Belmond Copacabana Palace, approximately 80 kilometres of beaches and the famous Corcovado, Sugarloaf mountains and Maracanã Stadium. While the city had in past had a thriving tourism sector, the industry entered a decline in the last quarter of the 20th century. Annual international airport arrivals dropped from 621,000 to 378,000 and average hotel occupancy dropped to 50% between 1985 and 1993.[124]

The fact that Brasília replaced Rio de Janeiro as the Brazilian capital in 1960 and that São Paulo replaced Rio as the country's commercial, financial and main cultural center during the mid-20th century, has also been cited as a leading cause of the decline.[125]

Rio de Janeiro's government has since undertaken to modernise the city's economy, reduce its chronic social inequalities, and improve its commercial standing as part of an initiative for the regeneration of the tourism industry.[125]

The city is an important global LGBT destination, 1 million LGBT tourists visiting each year.[126] The Rua Farme de Amoedo is located in Ipanema, a famous neighborhood in the South Zone of Rio de Janeiro. The street and the nearby beach, famous tourist spots, are remarkable for their popularity in the LGBT community. Rio de Janeiro is the most awarded destination by World Travel Awards in the South American category of "best destination".[127]

Education

The Portuguese language is the official and national language, and thus the primary language taught in schools. English and Spanish are also part of the official curriculum. There are also international schools, such as the American School of Rio de Janeiro, Our Lady of Mercy School, the Corcovado German School, the Lycée Français and the British School of Rio de Janeiro.

Educational institutions

The city has several universities and research institutes. The Ministry of Education has certified approximately 99 upper-learning institutions in Rio.[128]

The most prestigious university is the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. It is the fifth best in Latin America; the second best in Brazil, second only to the University of São Paulo; and the best in Latin America, according to the QS World University Rankings.[129][130]

Some notable higher education institutions are Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ); Federal University of the Rio de Janeiro state (UNIRIO); Rio de Janeiro State University (UERJ); Federal Rural University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRRJ, often nicknamed Rural); Fluminense Federal University (UFF); Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (PUC-Rio); Getúlio Vargas Foundation (FGV); Military Institute of Engineering (IME); Superior Institute of Technology in Computer Science of Rio de Janeiro (IST-Rio); College of Publicity and Marketing (ESPM); National Institute of Pure and Applied Mathematics (IMPA); Superior institute of Education of Rio de Janeiro (ISERJ) and Federal Center of Technological Education Celso Suckow da Fonseca (CEFET/RJ). There are more than 137 upper-learning institutions in whole Rio de Janeiro state.[131]

Educational system

Primary schools are largely under municipal administration, while the state plays a more significant role in the extensive network of secondary schools. There are also a small number of schools under federal administration, as is the case of Pedro II School, Colégio de Aplicação da UFRJ and the Centro Federal de Educação Tecnológica of Rio de Janeiro (CEFET-RJ). In addition, Rio has an ample offering of private schools that provide education at all levels. Rio is home to many colleges and universities. The literacy rate for cariocas aged 10 and older is nearly 95 percent, well above the national average.[132]

The Rio de Janeiro State University (public), Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (public), Brazilian Institute of Capital Markets (private) and Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (private) are among the country's top institutions of higher education. Other institutes of higher learning include the Colégio Regina Coeli in Usina, notable for having its own 3 ft (914 mm) narrow gauge[133] funicular railway on its grounds.[134]

In Rio, there were 1,033 primary schools with 25,594 teachers and 667,788 students in 1995. There are 370 secondary schools with 9,699 teachers and 227,892 students. There are 53 University-preparatory schools with 14,864 teachers and 154,447 students. The city has six major universities and 47 private schools of higher learning.[135]

Culture

Rio de Janeiro is a main cultural hub in Brazil. Its architecture embraces churches and buildings dating from the 16th to the 19th centuries, blending with the world-renowned designs of the 20th century. Rio was home to the Portuguese Imperial family and capital of the country for many years, and was influenced by Portuguese, English, and French architecture.[136]

Rio de Janeiro has inherited a strong cultural role from the past. In the late 19th century, there were sessions held of the first Brazilian film and since then, several production cycles have spread out, eventually placing Rio at the forefront of experimental and national cinema. The Rio de Janeiro International Film Festival[137] has been held annually since 1999.[138]

Rio currently brings together the main production centers of Brazilian television.[139] Major international films set in Rio de Janeiro include Blame it on Rio; the James Bond film Moonraker; the Oscar award-winning, critically acclaimed Central Station by Walter Salles, who is also one of Brazil's best-known directors; and the Oscar award-winning historical drama, Black Orpheus, which depicted the early days of Carnaval in Rio de Janeiro. Internationally famous, Brazilian-made movies illustrating a darker side of Rio de Janeiro include Elite Squad and City of God.

Rio has many important cultural landmarks, such as the Biblioteca Nacional (National Library), one of the largest libraries in the world with collections totalling more than 9 million items; the Theatro Municipal; the National Museum of Fine Arts; the Carmen Miranda Museum; the Rio de Janeiro Botanical Garden; the Parque Lage; the Quinta da Boa Vista; the Imperial Square; the Brazilian Academy of Letters; the Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro; and the Natural History Museum.

Literature

After Brazilian independence from Portugal in 1822, Rio de Janeiro quickly developed a European-style bourgeois cultural life, including numerous newspapers, in which most 19th-century novels were initially published in serial. Joaquim Manuel de Macedo's A Moreninha (1844) was perhaps the first successful novel in Brazil and inaugurates a recurrent 19th-century theme: a romantic relationship between idealistic young people in spite of cruelties of social fortune.

The first notable work of realism focusing on the urban lower-middle class is Manuel Antônio de Almeida's Memórias de um sargento de milícias (1854), which presents a series of picaresque but touching scenes, and evokes the transformation of a town into a city with suggestive nostalgia. Romantic and realist modes both flourished through the late 19th century and often overlapped within works.[140]

The most famous author of Rio de Janeiro, however, was Machado de Assis, who is also widely regarded as the greatest writer of Brazilian literature[141] and considered the founder of Realism in Brazil, with the publication of The Posthumous Memoirs of Bras Cubas (1881).[142] He commented on and criticized the political and social events of the city and country such as the abolition of slavery in 1888 and the transition from Empire to Republic with his numerous chronicles published in newspapers of the time.[143] Many of his short stories and novels, like Quincas Borba (1891) and Dom Casmurro (1899), are placed in Rio.

The headquarters of the Brazilian Academy of Letters is based in Rio de Janeiro. It was satirized by the novelist Jorge Amado in Pen, Sword, Camisole. Amado, himself, went on to be one of the 40 members of the Academy.

Libraries

The Biblioteca Nacional (National Library of Brazil) ranks as one of the largest libraries in the world. It is also the largest library in all of Latin America.[144] Located in Cinelândia, the National Library was originally created by the King of Portugal, in 1810. As with many of Rio de Janeiro's cultural monuments, the library was originally off-limits to the general public. The most valuable collections in the library include: 4,300 items donated by Barbosa Machado including a precious collection of rare brochures detailing the History of Portugal and Brazil; 2,365 items from the 17th and 18th centuries that were previously owned by Antônio de Araújo de Azevedo, the "Count of Barca", including the 125-volume set of prints "Le Grand Théâtre de l'Univers;" a collection of documents regarding the Jesuítica Province of Paraguay and the "Region of Prata;" and the Teresa Cristina Maria Collection, donated by Emperor Pedro II. The collection contains 48,236 items. Individual items of special interest include a rare first edition of Os Lusíadas by Luis de Camões, published in 1584; two copies of the Mogúncia Bible; and a first edition of Handel's Messiah.[145]

The Real Gabinete Português de Leitura (Portuguese Royal Reading Library) is located at Rua Luís de Camões, in the Centro (Downtown). The institution was founded in 1837 by a group of forty-three Portuguese immigrants, political refugees, to promote culture among the Portuguese community in the then capital of the Empire. The history of the Brazilian Academy of Letters is linked to the Real Gabinete, since some of the early meetings of the Academy were held there.[146]

Music

The official song of Rio de Janeiro is "Cidade Maravilhosa", which means "marvelous city". The song is considered the civic anthem of Rio, and is always the favourite song during Rio's Carnival in February. Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, are considered the centre of the urban music movement in Brazil.[147]

"Rio was popularised by the hit song "The Girl from Ipanema", composed by Antônio Carlos Jobim and Vinicius de Moraes and recorded by Astrud Gilberto and João Gilberto, Frank Sinatra, and Ella Fitzgerald. It is also the main key song of the bossa nova, a music genre born in Rio. A genre unique to Rio and Brazil as a whole is Funk Carioca. While samba music continues to act as the national unifying agent in Rio, Funk Carioca found a strong community following in Brazil. With its genesis in the 1970s as the modern black pop music from the United States, it evolved in the 1990s to describe a variety of electronic music associated with the current US black music scene, including hip hop, modern soul, and house music."[148]

Brazil's return to democracy in 1985 allowed for a new music expression which promoted creativity and experimentation in expressive culture, in a wave of Rock'n'roll that swept the 80s. Lobão emerged as the most legendary rocker in Brazil.[149] Commercial and cultural imports from Europe and North America have often influenced Brazil's own cultural output. For example, the hip hop that has stemmed from New York is localized into forms of musical production such as Funk Carioca and Brazilian hip hop. Bands from Rio de Janeiro also had influence in the mid-to-late development of the Punk in Brazil, and that of Brazilian thrash metal. Democratic renewal also allowed for the recognition and acceptance of this diversification of Brazilian culture.[150]

Some of the best singers in the history of Rio de Janeiro are Lobão, Tim Maia, Agepê, Emílio Santiago, Evandro Mesquita, Byafra, Erasmo Carlos, Elymar Santos, Gretchen, Latino, Kátia Cega, Rafael Ilha, Sérgio Mallandro e Wilson Simonal.

Theatre

.jpg)

Rio de Janeiro's Theatro Municipal is one of the most attractive buildings in the central area of the city. Home of one of the largest stages in Latin America and one of Brazil's best known venues for opera, ballet, and classical music, the building was inspired by the Palais Garnier, home of the Paris Opera. Construction of the Theatro Municipal began in 1905 following designs of the architect Francisco Pereira Passos. The statues on the top, of two women representing Poetry and Music, are by Rodolfo Bernardelli, and the interior is rich with furnishings and fine paintings. Inaugurated in 1909, the Teatro Municipal has close to 1,700 seats. Its interior includes turn of the century stained glass from France, ceilings of rose-colored marble and a 1,000 pound crystal bead chandelier surrounded by a painting of the "Dance of the Hours". The exterior walls of the building are dotted with inscriptions bearing the names of famous Brazilians as well as many other international celebrities.[151]

Cidade das Artes (City of Arts) is a cultural complex in Barra da Tijuca in the Southwest Zone of Rio de Janeiro, which was originally planned to open in 2004. Formally known as "Cidade da Música" (City of Music), it was finally inaugurated at the beginning of 2013. The project will host the Brazilian Symphony Orchestra becoming a main center for music as will be the largest modern concert hall in South America, with 1,780 seats. The complex spans approximately 90 thousand square metres (1 million square feet) and also features a chamber music hall, three theaters, and 12 rehearsal rooms. From the terrace there is a panoramic view of the zone. The building was designed by the French architect Christian de Portzamparc and construction was funded by the city of Rio de Janeiro.

Events

New Year's Eve

Every 31 December, 2.5 million people gather at Copacabana Beach to celebrate New Year's in Rio de Janeiro. The crowd, mostly dressed in white, celebrates all night at the hundreds of different shows and events along the beach. It is the second largest celebration only next to the Carnival. People celebrate the New Year by sharing chilled champagne. It is considered good luck to shake the champagne bottle and spray around at midnight. Chilled champagne adds to the spirit of the festivities.[152]

Rock in Rio

"Rock in Rio" is a music festival conceived by entrepreneur Roberto Medina for the first time in 1985, and since its creation, recognized as the largest music festival in the Latin world and the largest in the world, with 1.5 million people attending the first event, 700,000 attending the second and fourth, about 1.2 million attending the third, and about 350,000 people attending each of the 3 Lisbon events. It was originally organized in Rio de Janeiro, from where the name comes from, has become a world level event and, in 2004, had its first edition abroad in Lisbon, Portugal, before Madrid, Spain and Las Vegas, United States. The festival is considered the eighth best in the world by the specialized site Fling Festival.[153]

Carnival

Carnaval, is an annual celebration in the Roman Catholic tradition that allows merry-making and red meat consumption before the more sober 40 days of Lent penance which culminates with Holy or Passion Week and Easter. The tradition of Carnaval parades was probably influenced by the French or German courts and the custom was brought by the Portuguese or Brazilian Imperial families who had Bourbon and Austrian ancestors. Up until the time of the marchinhas, the revelry was more of a high class and Caucasian-led event. The influence of the African-Brazilian drums and music became more noticeable from the first half of the 20th century. Rio de Janeiro has many Carnaval choices, including the famous samba school (Escolas de Samba)[154] parades in the sambadrome exhibition center and the popular blocos de carnaval, street revelry, which parade in almost every corner of the city. The most famous ones are:

- Cordão do Bola Preta: Parades in the centre of the city. It is one of the most traditional carnavals. In 2008, 500,000 people attended in one day.[155] In 2011, a record 2 million people attended the city covering three different metro stations.

- Suvaco do Cristo: Band that parades in the Botanic Garden, directly below the Redeemer statue's arm. The name translates to 'Christ's armpit' in English, and was chosen for that reason.

- Carmelitas: Band that was supposedly created by nuns, but in fact is just a theme chosen by the band. It parades in Santa Teresa, a bairro from where one can see extensive panoramas.

- Simpatia é Quase Amor: One of the most popular parades in Ipanema. Translates as 'Friendliness is almost love'.

- Banda de Ipanema: The most traditional in Ipanema. It attracts a wide range of revellers, including families and a wide spectrum of the LGBT/Queer population (notably drag queens).

In 1840, the first Carnaval was celebrated with a masked ball. As years passed, adorned floats and costumed revelers became a tradition among the celebrants. Carnaval is known as a historic root of Brazilian music.[156]

Sports

Football

As in the rest of Brazil, association football is the most popular sport. The city's major teams are Flamengo, Vasco da Gama, Fluminense and Botafogo. Madureira, Bangu, Portuguesa, America and Bonsucesso are small clubs. Famous players born in the city include Ronaldo and Romário.[157]

Rio de Janeiro was one of the host cities of the 1950 and 2014 FIFA World Cups, for which on both occasions Brazil was the host nation. In 1950, the Maracanã Stadium hosted 8 matches, including all but one of the host team's matches. The Maracanã was also the location of the infamous tournament-deciding match between Uruguay and Brazil, where Brazil only needed a draw to win the final group stage and the whole tournament. Brazil ended up losing 2–1 in front of a home crowd of more than 199,000. In 2014, the Maracanã hosted seven matches, including the final, where Germany beat Argentina 1–0.[158]

| Club | League | Venue | Established (team) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flamengo | Série A | Maracanã Stadium

78,838 (173,850 record) |

1895 |

| Vasco da Gama | Série A | São Januário Stadium

24,880 (40,209 record) |

1898 |

| Fluminense | Série A | Maracanã Stadium

78,838 (173,850 record) |

1902 |

| Botafogo | Série A | Nilton Santos Stadium

46,931 (43,810 record) |

1894 |

| Madureira | Série D | Estádio Aniceto Moscoso

5,400 (10,762 record) |

1914 |

| Bangu | Série D | Estádio Moça Bonita

9,564 (17,000 record) |

1904 |

| Portuguesa | Série D | Estádio Luso Brasileiro

15,000 (18,725 record) |

1924 |

| Bonsucesso | Campeonato Carioca | Leônidas da Silva Stadium

13,000 (13,571 record) |

1913 |

| America | Campeonato Carioca Série B | Edson Passos

13,544 (9,861 record) |

1904 |

Olympics

.jpg)

On 2 October 2009, the International Olympic Committee selected Rio de Janeiro to host the 2016 Summer Olympics.[159] Rio made their first bid for the 1936 Summer Olympics, but lost to Berlin. They later made bids for the 2004 and 2012 Games, but failed to become a candidate city both times. Those games were awarded to Athens and London respectively.[160]

Rio is the first Brazilian and South American city to host the Summer Olympics. Rio de Janeiro also became the first city in the southern hemisphere outside of Australia to host the games – Melbourne in 1956 and Sydney in 2000. In July 2007, Rio successfully organized and hosted the XV Pan American Games.

Rio de Janeiro also hosted the 2011 Military World Games from 15–24 July 2011. The 2011 Military World Games were the largest military sports event ever held in Brazil, with approximately 4,900 athletes from 108 countries competing in 20 sports.[161]

Rio de Janeiro hosted the 2016 Olympics and Paralympics. The Olympic Games were held from 5 to 21 August 2016. The Paralympics were held from 7 to 18 September 2016.

Other sports

The city has a history as host of major international sports events. The Ginásio do Maracanãzinho was the host arena for the official FIBA Basketball World Championship for its 1954 and 1963 editions. Later, the Jacarepaguá circuit in Rio de Janeiro was the site for the Formula One Brazilian Grand Prix from 1978 to 1989. Rio de Janeiro also hosted the MotoGP Brazilian Grand Prix from 1995 to 2004 and the Champ Car event from 1996 to 1999. WCT/WQS surfing championships were contested on the beaches from 1985 to 2001. The Rio Champions Cup Tennis tournament is held in the spring. As part of its preparations to host the 2007 Pan American Games, Rio built a new stadium, Estádio Olímpico João Havelange, to hold 45,000 people. It was named after Brazilian ex-FIFA president João Havelange. The stadium is owned by the city of Rio de Janeiro, but it was rented to Botafogo de Futebol e Regatas for 20 years.[162] Rio de Janeiro has also a multi-purpose arena, the HSBC Arena.

The Brazilian Dance/Sport/Martial art Capoeira is very popular. Other popular sports are basketball, beach football, beach volleyball, Beach American Football, footvolley, surfing, kite surfing, hang gliding, motor racing, Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, sailing, and competitive rowing. Another sport that is highly popular in beaches of Rio is called "Frescobol" (pronounced [fɾe̞ɕko̞ˈbɔw]), a type of beach tennis. Rio de Janeiro is also paradise for rock climbers, with hundreds of routes all over the city, ranging from easy boulders to highly technical big wall climbs, all inside the city. The most famous, Rio's granite mountain, the Sugar Loaf (Pão de Açúcar), is an example, with routes from the easy third grade (American 5.4, French 3) to the extremely difficult ninth grade (5.13/8b), up to 280 metres (919 feet).

Horse racing events are held Thursday nights and weekend afternoons at Hipódromo da Gávea. An impressive place with excellent grass and dirt tracks, it runs the best horses in the nation. Hang gliding in Rio de Janeiro started in the mid-1970s and quickly proved to be well-suited for this town, because of its geography: steep mountains encounter the Atlantic Ocean, which provide excellent take-off locations and great landing zones on the beach.

One of the most popular sea sports in the city is yachting. The main yacht clubs are in Botafogo area that extends halfway between Copacabana and the center of town. Though the most exclusive and interesting is probably the Rio Yacht club, where high society makes it a point to congregate. Most yacht clubs are open to members only and gate crashing is not easy. Copacabana is also a great place to surf, as well as "Arpoador of Ipanema" beach and "Praia dos Bandeirantes". The sea at these beaches is rough and dangerous, and the best surfers from Brazil and other sites of the world come to these beaches to prove themselves.[163]

Transportation

Airports

The city of Rio de Janeiro is served by the following airports for use:

- Galeão–Antônio Carlos Jobim International Airport: used for all international and most of the domestic flights. Since August 2004, with the transfer of many flights from Santos-Dumont Airport, Rio de Janeiro International Airport has returned to being the main doorway to the city. Besides linking Rio to the rest of Brazil with domestic flights, Galeão has connections to 19 countries. It has a capacity to handle up to 30 million users a year in two passenger terminals. It is located 20 km (12 mi) from downtown Rio. The airport complex also has Brazil's longest runway at 4,000 m (13,123.36 ft), and one of South America's largest cargo logistics terminals. The airport is connected to the express bus service.[164]

- Santos Dumont Airport: used mainly by the services to São Paulo, some short and medium-haul domestic flights, and general aviation. Located on Guanabara Bay just a few blocks from the heart of downtown Rio, during the 1990s Santos-Dumont began to outgrow its capacity, besides diverging from its specialization on short-hop flights, offering routes to other destinations in Brazil. For this reason, in late 2004 Santos-Dumont returned to its original condition of operating only shuttle flights to and from Congonhas Airport in São Paulo, along with regional aviation. The passenger terminal has undergone extensive renovation and expansion, which increased its capacity to 9,9 million users a year. The airport is connected to the city light rail system (Rio de Janeiro Light Rail), which connects several transport systems to downtown.[165]

- Jacarepaguá-Roberto Marinho Airport: used by general aviation and home to the Aeroclube do Brasil (Brasil Flying club). The airport is located in the district of Baixada de Jacarepaguá, within the municipality of Rio de Janeiro approximately 30 km (19 mi) from the city center.[166]

Military airports include:

- Galeão Air Force Base: A Brazilian Air Force airbase, sharing some facilities with Galeão - Antônio Carlos Jobim International Airport;

- Santa Cruz Air Force Base: A Brazilian Air Force airbase. Formerly called Bartolomeu de Gusmão Airport, it was built by the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin. Today it is one of the most important Air Force Bases in Brazil;

- Afonsos Air Force Base: One of the historical Brazilian Air Force airbases. It is also the location of the University of the Air Force (Universidade da Força Aérea),[167] the Museu Aeroespacial,[168] and where air shows take place.

Ports

The Port of Rio de Janeiro is Brazil's third busiest port in terms of cargo volume, and it is the center for cruise vessels. Located on the west coast of the Guanabara Bay, it serves the States of Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, Minas Gerais, and Espírito Santo. The port is managed by Companhia Docas de Rio de Janeiro. The Port of Rio de Janeiro covers territory from the Mauá Pier in the east to the Wharf of the Cashew in the north. The Port of Rio de Janeiro contains almost seven thousand metres (23 thousand feet) of continuous wharf and an 883-metre (2,897-foot) pier. The Companhia Docas de Rio de Janeiro administers directly the Wharf of the Gamboa general cargo terminal; the wheat terminal with two warehouses capable of moving 300 tons of grains; General Load Terminal 2 with warehouses covering over 20 thousand square metres (215 thousand square feet); and the Wharves of Are Cristovao with terminals for wheat and liquid bulk.[169]

At the Wharf of Gamboa, leaseholders operate terminals for sugar, paper, iron and steel products. Leaseholders at the Wharf of the Cashew operate terminals for roll-on/roll-off cargoes, containers, and liquid bulk. In 2004, the Port of Rio de Janeiro handled over seven million tons of cargo on almost 1700 vessels. In 2004, the Port of Rio de Janeiro handled over two million tons of containerized cargo in almost 171 thousand TEUs. The port handled 852 thousand tons of wheat, more than 1.8 million tons of iron and steel, over a million tons of liquid bulk cargo, almost 830 thousand tons of dry bulk, over five thousand tons of paper goods, and over 78 thousand vehicles. In 2003, over 91 thousand passengers moved through the Port of Rio Janeiro on 83 cruise vessels.[170]

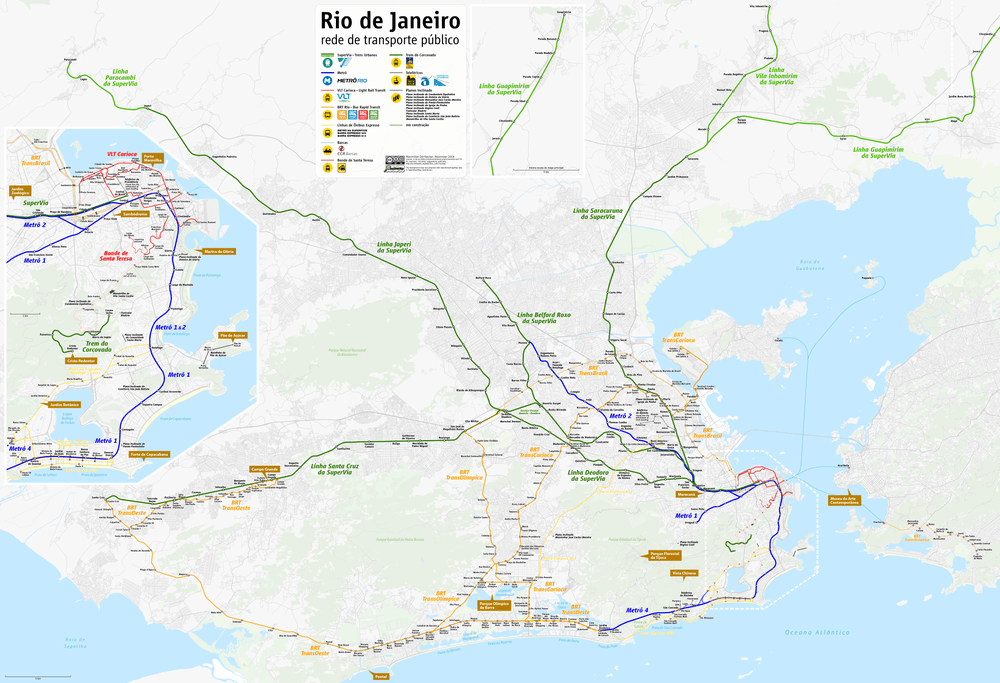

Public transportation