Northeast Region, Brazil

The Northeast Region of Brazil (Portuguese: Região Nordeste do Brasil; [ʁeʒiˈɐ̃w̃ nɔʁˈdɛstʃi du bɾaˈziw]) is one of the five official and political regions of the country according to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics. For the socio-geographic area see Nordeste (socio-geographic division). Of Brazil's twenty-six states, it comprises nine: Maranhão, Piauí, Ceará, Rio Grande do Norte, Paraíba, Pernambuco, Alagoas, Sergipe and Bahia, along with the Fernando de Noronha archipelago (formerly a separate territory, now part of Pernambuco).

Northeast Region Região Nordeste | |

|---|---|

Location of Northeast Region in Brazil | |

| Coordinates: 12°58′S 38°31′W | |

| Country | Brazil |

| Largest cities | Salvador (by city proper) Recife (by metro pop.) Fortaleza (by pop. density) |

| States | Alagoas, Bahia, Ceará, Maranhão, Paraíba, Pernambuco, Piauí, Rio Grande do Norte, Sergipe |

| Area | |

| • Region | 1,558,196 km2 (601,623 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 3rd |

| Population (2015 followed census) | |

| • Rank | 2nd |

| • Density rank | 3rd |

| • Urban | 71.5% |

| GDP | |

| • Year | 2014 estimate |

| • Total | R$805,099,000,000 (3rd) |

| • Per capita | R$14,329.13 (5th) |

| HDI | |

| • Year | 2017 |

| • Category | 0.710 – high (5th) |

| • Life expectancy | 69 years (5th) |

| • Infant mortality | 33.2 per 1,000 (1st) |

| • Literacy | 85,2% (5th) |

| Time zone | UTC-03 (BRT) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-02 (BRST) |

Chiefly known as Nordeste ("Northeast") in Brazil, this region was the first to be discovered and colonized by the Portuguese and other European peoples, playing a crucial role in the country's history. Nordeste's dialects and rich culture, including its folklore, cuisines, music and literature, became the most easily distinguishable across the country. To this day, Nordeste is known for its history and culture, as well as for its natural environment and its hot weather.

Nordeste stretches from the Atlantic seaboard in the northeast and southeast, northwest and west to the Amazon Basin and south through the Espinhaço highlands in southern Bahia. It encloses the São Francisco River and drainage basin, which were instrumental in the exploration, settlement and economic development of the region. The region lies entirely within the earth's tropical zone and encompasses Caatinga, Atlantic Forest and part of the Cerrado ecoregions. The climate is hot and semi-arid, varying from xeric in Caatinga, to mesic in Cerrado and hydric in the Atlantic Forest.

The Northeast Region represents 18% of Brazilian territory, has a population of 53.6 million people, 28% of the total population of the country, and contributes 13.4% (2011) of Brazil's GDP. Nearly three quarters of the population live in urban areas clustered along the Atlantic coast and about 15 million people live in the hinterland. It is an impoverished region: 43.5% of the population lives in poverty, defined as less than $2/day.[1]

Each of the states' capitals are also its largest cities, and they include Salvador, Recife, Fortaleza and São Luís, all of which are coastal cities with a population above one million.[2]

Nordeste has nine international airports,[Note 1] and the region has the second largest number of passengers (roughly 20%) in Brazil.

Geography and climate

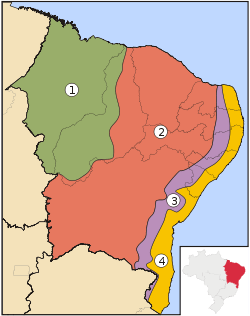

1 • Meio-Norte

2 • Sertão

3 • Agreste

4 • Zona da Mata

Zona da Mata ("Forest Zone")

The Zona da Mata comprises the rainforest zones of Nordeste (part of the Atlantic Forest or Mata Atlântica) in the humid eastern coast, where the region's largest capital cities are also located. The forest area was much larger before suffering from centuries of deforestation and exploration. For many years, sugar cane cultivation in this region was the mainstay of Brazil's economy, being superseded only when coffee production developed in the late 19th century. Sugar cane is cultivated on large estates whose owners maintain tremendous political influence.

Agreste

Since the escarpment does not generate any further rainfall on its slopes from the lifting of the trade winds, annual rainfall decreases steadily inland. After a relatively short distance, there is no longer enough rainfall to support tropical rainforest, especially since the rainfall is extremely erratic from year to year. This transitional zone is known as the agreste and because it is located on the steep escarpment, was not generally used whilst flatter land was abundant. Today, with irrigation water available, however, the agreste, as its name suggest, is a major farming region. Despite containing no major city, it contains well developed medium large cities such as Caruaru, Campina Grande and Arapiraca.

Sertão ("Backlands")

In Portuguese, the word sertão (Portuguese pronunciation: [sehˈtɐ̃w̃], meaning "backcountry" or "outback") first referred to the vast hinterlands of Asia and South America that Lusitanian explorers encountered. In Brazil, the geographical term referred to backlands away from the Atlantic coastal regions where the Portuguese first settled in South America in the early sixteenth century.

Geographically, the Sertão consists mainly of low uplands that form part of the Brazilian Highlands. Most parts of the sertão are between 200 and 500 meters above sea level, with higher elevations found on the eastern edge in the Planalto da Borborema, where it merges into a sub-humid region known as agreste, in the Serra da Ibiapaba in western Ceará and in the Serro do Periquito of central Pernambuco. In the north, the Sertão extends to the northern coastal plains of Rio Grande do Norte state, whilst in the south it fades out in the northern fringe of Minas Gerais.

Because the Sertão lies close to the equator, temperatures remain nearly uniform throughout the year and are typically tropical, often extremely hot in the west. However, the sertão is distinctive in its low rainfall compared to other areas of Brazil. Because of the relatively cool temperatures in the South Atlantic Ocean, the intertropical convergence zone remains north of the region for most of the year, so that most of the year is very dry.

Although annual rainfall averages between 500 and 800 millimeters over most of the sertão and 1300 millimeters on the northern coast at Fortaleza, it is confined to a short rainy season. This season extends from January to April in the west, but in the eastern Sertão it generally occurs from March to June. However, rainfall is extremely erratic and in some years the rains are minimal, leading to catastrophic drought. The drought duration has increased over the last 36 years. the drought occurred in 2012-2016 hit the longest drought in its drought history. [3] Because of this vulnerability to the climate, Sertão is also known as a “polygon of drought.” [4] More frequent, severer and longer droughts are estimated to hit the region over the next 90 years under the effect of global warming.[5]

Hydrology

The Northeast region comprises the drainage basins of the São Francisco, Canindé, and Parnaíba Rivers.

Geology and topography

Geographically, Nordeste consists chiefly of an eroded continental craton with many low hills and small ranges. The highest peaks are around 1,850 metres (6,070 ft) in Bahia, while further north there are no peaks above 1,123 metres (3,684 ft). On its northern and western side, the plateaus fall steadily to the coast and into the basin of the Tocantins River in Maranhão, but on the eastern side it falls off quite sharply to the coast except in the valley of the São Francisco river. The steep slopes and long cliffs of the eastern coastline are known as "The Great Escarpment".

The escarpment serves an extremely important climatic function. Because for most of the year Nordeste is out of reach of the Intertropical Convergence Zone, the easterly trade winds blow across the region, giving abundant rainfall to the coast but producing clear, dry conditions inland where the escarpment blocks moisture flow. This gives rise to four distinct regions, the zona da mata on the coast, the agreste on the escarpment, sertão beyond and the Mid north.

Conservation and biodiversity

Summary of threats

- Deforestation

- Degradation of Mangroves and Restingas

- Poaching and Animal Trading

- Infrastructure

- Dams

- Mining

- Tourism Development

- Introduction of Alien Species

Protected areas in Brazil

Brazil is characterized by a complex system of conservation units. As a matter of fact, 2.61% of Brazil's national territory is covered by strict protected areas and 5.52% by areas dedicated to sustainable development, for a total of 8.13% of the national territory. However, this figure is slightly overestimated, since many areas of environmental protection (APAs) include one or more conservation units dedicated to indirect use.

The conservation units managed by Instituto Brasileiro de Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais Renovaveis (IBAMA) cover approximately 45 million hectares and include about 256 conservation units of direct or indirect use which include Environmental protection areas, Biological reserves, Ecological stations, National forests, Areas of relevant ecological interest, National parks, several Private natural heritage reserves, and Wildlife sanctuaries. There are also several conservation units that are managed by the Brazilian states, and cover about 22 million hectares. Moreover, there are wetlands protected as Ramsar sites:

- Reserva de Desenvolvimento Sustentado Mamirauá

- Área de Proteção Ambiental da Baixada Maranhense

- Área de Proteção Ambiental da Serra de Baturité

- Parque Nacional da Lagoa do Peixe

- Área de Proteção Ambiental das Reentrâncias Maranhenses

- Parque Estadual Marinho do Parcel de Manuel Luiz

- Parque Nacional do Araguaia

- Parque Nacional do Pantanal Matogrossense

- Reseva Particular do Patrimônio Natural do SESC Pantanal

and Biosphere Reserves:

- Reserva da Biosfera da Mata Atlântica

- Reserva da Biosfera do Cerrado

- Reserva da Biosfera do Pantanal

Main Categories of Protected Areas

Environment protection area: it is a rather large area characterized by a considerable population density and with abiotic, biotic, aesthetic, or cultural features of great importance, above all for the quality of life and well-ness of man. Protecting biological diversity, regulating the settlement processes, and ensuring the sustainable use of natural resources are among its main aims.

Wildlife refuge: this protected area aims at protecting the natural environments ensuring the conditions for the survival and reproduction of species or communities belonging to the local flora and to resident or migratory fauna.

Biological reserve: it aims at strictly safeguarding the natural aspects within its borders, avoiding direct human interference or environmental changes, through measures to recover altered ecosystems and management actions necessary to recover or maintain the natural balance, biological diversity, and natural ecological processes.

Ecological station: it aims at safeguarding nature and carrying out scientific research activities.

National park: it aims at preserving natural ecosystems, giving the opportunity to carry out scientific research activities or developing environmental education and interpretation activities, as well as promoting recreational activities at direct contact with nature and ecological tourism.

Area of relevant ecological interest: not very large area, with a scarce population density and extraordinary natural features of great importance at a regional and local level.

Sustainable development reserve: natural area including traditional populations whose existence is based on sustainable systems of exploitation of the natural resources which have been developed generation after generation and adapted to local ecological conditions. They play an essential role in the protection of nature and maintenance of biological diversity.

Source: Instituto Brasileiro de Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais Renovaveis (IBAMA), Ministério do Meio Ambiente

History

- Main articles: Colonial Brazil, History of Brazil

Before the arrival of Europeans, Nordeste was inhabited by indigenous peoples, mostly speaking languages of the Tupi–Guarani family.[6][7] In the Sertão region, Tapuia tribes could also be found.[6][8]

It was the first area discovered in Brazil, when roughly 1,500 Portuguese arrived on April 22, 1500, under the command of Pedro Álvares Cabral at Porto Seguro, in what is now the state of Bahia.

The coast of Nordeste saw the first economic activity of the country, namely the extraction and export of pau Brasil, or brazilwood. Indigenous peoples helped Europeans with the extraction of brazilwood in exchange for spices. They also engaged in an exchange of goods (Portuguese: escambo), trading things like animal skins for knives and other valuables. Brazilwood was highly valued in Europe where it was used to make violin bows (especially the Pau de Pernambuco variety) and for the red dye it produced. Countries like France, which disagreed with the Treaty of Tordesillas (a papal bull decreed by the Spanish-born Pope Alexander VI in 1493 which sought to divide South America between the Spanish and the Portuguese), launched many attacks on the coast to steal the wood.

Soon after their arrival, Portuguese settlers began to displace native peoples and enslave them as field laborers, leading to conflicts in which many natives died. These conflicts were one contributor to the decline of the indigenous population, which intensified as colonization, commercial interest, and disease escalated in the region. After resistance from indigenous peoples and opposition to their enslavement from the Jesuits[9], the Portuguese colonials began importing black African slaves in 1530, largely to Bahia.

In 1552, the seat of the first Catholic bishop of Brazil was established in Nordeste.

French colonists not only tried to settle in present-day Rio de Janeiro, from 1555 to 1567 (the so-called France Antarctique episode), but also in present-day São Luís, from 1612 to 1614 (the so-called France Equinoxiale). The Dutch, also opposed to the Treaty of Tordesillas, plundered Nordeste's coast, sacked Bahia in 1604, and even temporarily captured Salvador, which had been Brazil's first capital and general seat of government since 1549. However, the Portuguese soon regained control of Salvador, and the Dutch were unable to recapture it, despite repeated attempts.[10]

In 1630, the Dutch captured Pernambuco and made Recife (Dutch: Mauritsstad) their capital. By 1640, they had set up more permanently in Nordeste and controlled a long stretch of coast that was most accessible to Europe without, however, penetrating the interior. The colonists of the Dutch West India Company (WIC) in Brazil were under constant siege despite the presence in Recife of John Maurice of Nassau as governor. To help fight the Portuguese, the WIC sought the support of native peoples. By 1635, the majority of Tupi, mostly from Rio Grande do Norte and Paraíba, had given their support to the Dutch, as they viewed the Portuguese as more brutal and believed that they would be better off if the Dutch remained in Brazil. The military aid provided by the Tupi population proved to be useful in 1645, when Portuguese colonists who had remained in Dutch-controlled territory began to revolt. Tupi mediators such as Poty and Paraupaba were instrumental in maintaining strong Dutch-Tupi relations during the struggle against the Portuguese. At the end of 1653, the Portuguese succeeded in capturing Recife, effectively ending Dutch Brazil and culminating in their surrender in 1654.[11][10]

Slave resistance began during the colonial era, in the 17th century, and eventually led to the formation of quilombos, or settlements of runaway and free-born African slaves. The Quilombo dos Palmares, the largest and most well-known of these settlements, was founded around 1600 in the Serra da Barriga hills, in the present state of Alagoas. Palmares, at the height of its power, was an independent, self-sustaining republic, hosting a population of over 30,000 free African men, women and children. There were over 200 buildings in the community, a church, four smithies, and a council house. Although Palmares managed to defend itself from the Dutch military and the Portuguese colonials for several decades, it was finally taken and destroyed and its leader Zumbi dos Palmares was captured and beheaded. His head was then displayed in a public plaza in Recife.

Although the King of Portugal had abolished the enslavement of native peoples in 1570, it continued until the Marquis of Pombal declared them to be 'free men' in 1755.[12] However, by that time the practice was already rare.

Salvador remained the colonial capital until 1763 when it was succeeded by Rio de Janeiro, the new economic power center of that era.

In 1850, the Eusébio de Queirós Law was passed, abolishing the international slave trade in Brazil. Following the ban, some slaves from Nordeste were sold to the Southeast region of Brazil (Portuguese: Sudeste), primarily to the state of Rio de Janeiro. The percentage of slaves in Salvador dropped from 41.6% of the population in 1775 to 27.5% in 1855.[13]

Before the rise of Sudeste, Nordeste was the center of the African slave trade in Brazil, the center of the sugar industry in Brazil, and Brazil's main seaport.

Cangaceiros

Independent armed groups emerged in the Brazilian Northeast, which used guerrilla tactics to fight and were wanting to avenge crimes against family members or friends as well as fight for food and ammunition to their members, and often working for landlords who evicted the workers of the estates who reacted against exploitation in the county.

They were formed by people of humble origin, usually from the field, under the leadership of a chief who imposed their own concept of morality, honor, justice and piety.[14]

Gangs were pursuing isolated goals, sometimes even fighting among themselves, and had its heyday between 1922 and 1930, when terror spread throughout the semi-arid Northeast and were chased by troops from seven states; Bahia, Sergipe, Alagoas, Pernambuco, Paraíba, Rio Grande do Norte and Ceará, the officials even using airplanes in repeated, unsuccessful, search attempts.

In the struggle to capture the leader of the most feared of these bands, Virgolino Ferreira da Silva, Lampião, the Brazilian government went on to publish wanted posters promising 50,000,000 réis to whoever brought in Lampião "dead or alive."

Deeply knowledgeable of the caatinga, the gangs had support from local farmers, politicians, peasants and priests, not only for fear of the bandits, but for need of their services. The rank of Captain Virgolino Ferreira, for example, was given by Father Cícero do Juazeiro.

Besides Lampião, other bandits and outlaws have also become myths in the Northeast, outlaws like Antônio Silvino Corisco, o Diabo Louro, (the Blond Devil). The entry of women into banditry happened in 1930 when Maria Bonita became fellow Cangaceiro and followed Lampião's gang. Although the highwaymen took momentum in the early 1920s, the existence of armed groups in the Northeast comes from colonial times.

And one of the first of outlaws ever heard was The Cabeleira, in the second half of the 18th century, was active in rural areas close to Recife. According to scholars, one of the factors that contributed to the proliferation of gangs was the great drought that decimated the Northeast in 1877: extreme poverty and hunger caused thousands in the Sertão, (hinterland), with no prospect of survival, to depart for plunder, paving the way for the world of cangaceiros.

Banditry is at the origin in the very form of colonization in the Brazilian Northeast, where, financed by the Crown, the pioneers invaded the Sertão, fell forests, landmarks and paid the gunmen and bandits to eliminate the native populations to react to the occupation of their land.

The private armies maintained by the Northeastern colonels who owned the land since the Captaincies also differed on almost nothing, its methods, the bands of outlaws. The highwaymen was one of the most turbulent and contradictory times in Brazilian history and still comes up in a heated controversy: that the outlaws would have been righteous if they didn't become bloodthirsty bandits.

The end of the cangaceiros took place in 1938, when Lampião's gang was slaughtered, on the banks of the São Francisco River in Angicos, Alagoas. Corisco, o Diabo Louro, survived until 1940, but almost without doing anything to keep the promise to "avenge the death of Lampião."

Political subdivisions

The regions of Brazil do not have their own governmental or administrative bodies, but they are well defined.[Note 2] Their boundaries and constituent states are part of the recognized geopolitical structure of the country. The Northeast Region is composed of nine states, with 1793 municipalities[Note 3] and two special municipalities, Saint Peter and Saint Paul Archipelago and Fernando de Noronha Archipelago; there are no unincorporated areas. Brazilian states are divided into Mesoregions, and Mesoregions into Microregions, each region representing a group of municipalities. These regions were created by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics for statistical purposes and do not, therefore, constitute an administrative area. Municipalities are analogous to counties in states of the United States; a city is the urban area of the municipality, and always has the same name as the municipality.

A municipality may include cities other than the one which gives it its name. The largest state of the Northeast region in terms of area, population and economic output is Bahia; its capital Salvador is the largest city of Nordeste.

| State | Symbol | Area km2 | Municipalities | Population 2014 IBGE |

HDI 2010 |

HDI 2018 |

GDP (R$x1000) 2014 IBGE[15] |

GDP per capita 2014 (R$) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AL | 27,768 | 102 | 3,327,551 | 0.631 | 0.719 | 40,975,000 | 12.335,44 | |

| BA | 564,693 | 417 | 15,150,143 | 0.660 | 0.735 | 223,930,000 | 14.803,95 | |

| CE | 148,826 | 184 | 8,867,448 | 0.682 | 0.734 | 126,054,000 | 14.255,05 | |

| MA | 331,983 | 217 | 6,861,924 | 0.639 | 0.706 | 76,842,000 | 11.216,37 | |

| PB | 56,440 | 223 | 3,950,359 | 0.658 | 0.736 | 52,936,000 | 13.422,42 | |

| PE | 98,312 | 185 | 9,297,861 | 0.673 | 0.737 | 155,143,000 | 16.722,05 | |

| PI | 251,529 | 223 | 3,198,185 | 0.646 | 0.716 | 37,723,000 | 11.808,08 | |

| RN | 52,797 | 167 | 3,419,550 | 0.684 | 0.751 | 54,023,000 | 15.849,33 | |

| SE | 21,910 | 75 | 2,227,294 | 0.665 | 0.747 | 37,472,000 | 16.882,71 | |

| Northeast | NE | 1,558,196 | 1,793 | 56,300,315 | 0.659 | 0.731 | 805,099,000 | 14.329,13 |

| Metropolitan area | Population (2010 census)[16] |

|---|---|

| Recife | 3,690,547 |

| Fortaleza | 3,615,767 |

| Salvador | 3,573,973 |

| Natal | 1,351,004 |

| São Luís | 1,331,181 |

| João Pessoa | 1,198,576 |

| Maceió | 1,156,364 |

| Teresina | 1,150,959 |

| Aracaju | 835,816 |

Economy

Northeastern Brazil's economy is based on coffee, cocoa, sugar cane, livestock, manufacturing and textiles, as well as forest products. Some time ago, at São Francisco River Valley (between the states of Bahia and Pernambuco), fruits for export started being produced, too. At the seaside and the continental platform of the region, the main activity is the exploitation of oil, which is later processed in the state of Bahia, and natural gas in Maranhão. Major industries (clothing, food, small machinery) are in the main metropolitan areas of Nordeste.

Official reclamation activities have spurred the construction of numerous dams and hydroelectric projects, especially on the São Francisco River. In the 1960s a violent dictatorship in Brazil created a resilient state of poverty in the region.[19] Development of tourism is a concerted, ongoing effort.[20] The São Francisco River is responsible for the regional production of energy and it also bathes the states of Bahia, Sergipe, Alagoas and Pernambuco. Nordeste has a number of beaches with clear, warm water. Beyond tourism, Nordeste also develops its industrial sector. Every day, important investors from many countries come to this region to search for new opportunities. The governments try to motivate the inflow of new investment money, based on the needs of its states.[21]

Sugar cane is the main agricultural product of the region, produced mainly in Alagoas, Pernambuco and Paraíba. It is also important to highlight the soybean (Bahia, Maranhão and Piauí), cotton (Bahia, Maranhão, Ceará, Paraíba and Rio Grande do Norte), rice (Maranhão), tobacco (Alagoas and Bahia) and cashew trees (Piauí, Paraíba and Ceará), as well as fine grapes, mango, melon, acerola and other fruits for domestic consumption and export (Pernambuco, Bahia and Rio Grande do Norte). Also noteworthy are the plantations of Cacau in Ilhéus and Itabuna, coffee plantations in the Planalto da Conquista, Vitória da Conquista region and beans in Irecê, in the state of Bahia.

In terms of livestock, cattle is the most commonly raised. The largest cattle herds are in Bahia (10,229,459 heads), followed by Maranhão (5,592,007), Ceará (2,105,441), Pernambuco (1,861,570) and Piauí (1,560,552). In the hinterland, producers often suffer losses due to constant droughts. Goats, who are more resistant to drought, swine, sheep and birds are also raised.

Tourism and recreation

- See Also: List of beaches#Brazil, List of national parks of Brazil, Brazil#Economy#Tourism

Tourism has grown significantly in the Region in the last decades, showing the high potential of each State.

Besides the capitals, most coastal cities of the Northeast Region have natural amenities, such as the Abrolhos Marine National Park, Itacaré, Comandatuba Island, Costa do Sauípe, Canasvieiras and Porto Seguro, in the State of Bahia; the Marine National Park of Fernando de Noronha, Porto de Galinhas beach in the State of Pernambuco; tropical paradises, such as Canoa Quebrada and Jericoacoara, on the coast of Ceará, as well as the places to practice free flight, as Quixadá and Sobral; and Lençóis Maranhenses, embellishing the coast of Maranhão State, among many others. In the interior area, National Parks of Serra da Capivara and Sete Cidades, both in the State of Piauí; João Pessoa, in the State of Paraíba; Chapada Diamantina, in the State of Bahia; and many other attractions.

The economy is based on tourism (in coastal or historical cities) or agriculture. The tourist industry is based largely on the beaches, which attract thousands of tourists per year, not only from other regions of Brazil but also many from Europe (especially Italy, Portugal, Germany, France, United Kingdom and Spain), the United States, and Australia. There are two recognized nudist beaches in Nordeste: Tambaba Beach north of Recife, Paraiba, and Massarandupio Beach 100 km north of Salvador, Bahia.

Infrastructure

Educational institutions

- Universidade Federal de Pernambuco (UFPE)

- Universidade Federal da Bahia (UFBA)

- Universidade da Integração Internacional da Lusofonia Afro-Brasileira (UNILAB)

- Universidade Federal do Ceará (UFC)

- Universidade Federal da Paraíba (UFPB)

- Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN)

- Universidade Federal de Sergipe (UFS)

- Universidade Federal de Alagoas (UFAL)

- Universidade Federal do Maranhão (UFMA)

- Universidade Federal do Piauí (UFPI)

- and many others.

International airports

- AJU Santa Maria Airport (Sergipe), Aracaju, Sergipe

- MCZ Zumbi dos Palmares International Airport, Maceio, Alagoas

- PHB Parnaíba-Prefeito Dr. João Silva Filho International Airport Parnaiba, Piaui

- SLZ Marechal Cunha Machado International Airport, Sao Luis, Maranhão

- NAT Greater Natal International Airport, Natal, Rio Grande do Norte

- FOR Pinto Martins International Airport, Fortaleza, Ceará

- JPA Presidente Castro Pinto International Airport, Joao Pessoa, Paraíba

- REC Guararapes International Airport, Recife, Pernambuco

- SSA Deputado Luís Eduardo Magalhães International Airport, Salvador, Bahia

Oil refineries

- Lubnor (Petrobras), Fortaleza 82,000 bbl/d (13,000 m3/d)

Seaports

- Mucuripe port, Ceará

- Suape port, Ipojuca, Pernambuco

- Aratu Port, Bahia

Railroads

Planned for completion in 2013(It is now 2020?), a new railway will link Suape to the north-eastern interior. The federal government began construction in 1990, but it was postponed due to a shortage of money and only resumed in 2006. A second branch will travel north to the port of Pecém, which is also being expanded. There, the Ceará state government is setting up an institute to provide railroad travel for 12,000 workers a year, while Petrobras is also building another refinery. Paulo Roberto Costa, its downstream director, envisages trains transporting soybeans, corn, and iron ore from the interior to the ports, and returning with oil. Journey times to Europe and America will be three or four days less than from south-eastern ports. The 1,728-km line will one day carry 30 million tonnes of cargo a year.

The North-South railway and the Carajás railray in Maranhão are important logistics corridors, transporting the iron ore from the Serra dos Carajás in Pará and draining the agricultural production (soybeans, corn, cotton) of southern Maranhão, Tocantins, Goiás and Mato Groso, to the ports of Itaqui and Ponta da Madeira, in São Luís. Other products are also transported, such as cellulose and fuels.[22]

Mines

Hydroelectric dams and reservoirs

Brazil counts on hydroelectricity for more than 80% of its electricity.

Alagoas / Sergipe

- Xingó Hydroelectric Power Plant 3162

Bahia

- Apollonius Sales (Moxoto) Hydroelectric Power Plant 400

- Paulo Afonso Complex Hydroelectric Power Plant 1417.2

- Paulo Afonso IV Hydroelectric Power Plant 2642.4

- Sobradinho Hydroelectric Power Plant 1050

Maranhão

- Boa Esperanca (Castelo Branco) Hydroelectric Power Plant 237.4

- Estreito Hydroelectric Plant- 1.087

Pernambuco

- Luiz Gonzaga (Itaparica) Hydroelectric Power Plant 1479.6

In 2018, in Maranhão, natural gas exploration in the Parnaíba Basin has the capacity to produce 8.4 million m³ of gas per day, exploited by Eneva, with the implementation of 153 km of gas pipelines, at the cost of R $ 9 billion. Such production is destined for the production of electric energy in the Parnaíba Power Station, with 1.4 GW of capacity. The thermal power stations has important composition in the generation of energy in the region, with other examples being the Campina Grande Power Starion, the Pecém Power Station and the Jorge Lacerda Power Station, among others.[23]

In 2017, due to low levels of reservoirs, wind energy accounted for 50% of the electric power generation in the region, with the states of Rio Grande do Norte, with 3,722 MW and 137 parks; Bahia, with 2,594 MW and 100 parks; Ceará, with 1,950 MW and 75 parks; Piauí, with 1,443 MW and 52 parks; Pernambuco, with 781 MW and 34 parks; Maranhão, with 220 MW and 8 parks; and Paraíba, with 157 MW and 15 parks. [24]

New investments, seeking to diversify the northeastern energy matrix and promote energy security, allowed in 2017 the start-up of the Solar Lapa Park (BA), with 158 MW, Solar Ituverava Park (BA), with 254 MW, and the Solar Park Nova Olinda (PI), with 292 MW, considered the largest solar parks in Latin America. In 2018, the Solar Parque Horizonte (BA) was inaugurated, with 103 MW.[25]

Demographics

Urban areas and rural areas

Nordeste's major cities are almost all on the Atlantic coast. Some exceptions can be seen, however, like Petrolina-Juazeiro conurbation Bahia/Pernambuco (population over 500,000) on the São Francisco River and Teresina-Timon conurbation Piaui (population nearly 1,000,000) on the Parnaiba River.

Good rural areas are scarce and generally they are all near the coast, or in the west of Maranhão, and are mainly used for exportation products. In the semi-arid areas of the Northeast Region, rural areas do exist, but rain is scarce in the region; rural areas in the interior are generally based on subsistence agriculture. Fazendas (large farms) are common in the interior, where cattle-rasing and the cultivation of tropical fruit is often practiced. Also, in the areas where water is scarce local politicians often use the promise of irrigation projects as a bargaining chip to win elections.

Ethnic groups

Northeastern Brazilians are a result of the mixing of Europeans, Africans and Native Americans. African ancestry is significant particularly in the coastal areas, and especially in Bahia, Pernambuco and Maranhão. Native American ancestry is also present in all states, though more significantly in Ceará and Maranhão. Northeastern Brazilians also have a significant degree of European ancestry.

The racial makeup of the region is considered to be one of the primary reasons for which Northeastern Brazilians are often the target of prejudice and discrimination within Brazil, with other reasons including the region's comparative poverty and its leftist political leanings.[26][27][28][29]

Ethnic composition of Northeast Brazil compared to other regions

The composition of the Northeast of Brazil compared to other regions of Brazil according to autosomal genetic studies focused on the Brazilian population (which has been found to be a complex melting pot of European, African and Native Americans components):

A 2015 autosomal genetic study, which also analysed data of 25 studies of 38 different Brazilian populations concluded that: European ancestry accounts for 62% of the heritage of the population, followed by the African (21%) and the Native American (17%). The European contribution is highest in Southern Brazil (77%), the African highest in Northeast Brazil (27%) and the Native American is the highest in Northern Brazil (32%).[30]

| Region[30] | European | African | Native American |

|---|---|---|---|

| North Region | 51% | 16% | 32% |

| Northeast Region | 58% | 27% | 15% |

| Central-West Region | 64% | 24% | 12% |

| Southeast Region | 67% | 23% | 10% |

| South Region | 77% | 12% | 11% |

An autosomal study from 2013, with nearly 1300 samples from all of the Brazilian regions, found a pred. degree of European ancestry combined with African and Native American contributions, in varying degrees. 'Following an increasing North to South gradient, European ancestry was the most prevalent in all urban populations (with values up to 74%). The populations in the North consisted of a significant proportion of Native American ancestry that was about two times higher than the African contribution. Conversely, in Nordeste, Center-West and Southeast, African ancestry was the second most prevalent. At an intrapopulation level, all urban populations were highly admixed, and most of the variation in ancestry proportions was observed between individuals within each population rather than among population'.[31]

| Region[32] | European | African | Native American |

|---|---|---|---|

| North Region | 51% | 17% | 32% |

| Northeast Region | 56% | 28% | 16% |

| Central-West Region | 58% | 26% | 16% |

| Southeast Region | 61% | 27% | 12% |

| South Region | 74% | 15% | 11% |

A 2011 autosomal DNA study, with nearly 1000 samples from all over the country ("whites", "pardos" and "blacks"), found a major European contribution, followed by a high African contribution and an important Native American component.[33] The study showed that Brazilians from different regions are more homogeneous than previously thought by some based on the census alone. "Brazilian homogeneity is, therefore, a lot greater between Brazilian regions than within Brazilian regions."[34]

| Region[33] | European | African | Native American |

|---|---|---|---|

| Northern Brazil | 68.80% | 10.50% | 18.50% |

| Northeast of Brazil | 60.10% | 29.30% | 8.90% |

| Southeast Brazil | 74.20% | 17.30% | 7.30% |

| Southern Brazil | 79.50% | 10.30% | 9.40% |

According to an autosomal DNA study from 2010, a new portrayal of each ethnicity contribution to the DNA of Brazilians, obtained with samples from the five regions of the country, has indicated that, on average, European ancestors are responsible for nearly 80% of the genetic heritage of the population. The variation between the regions is small, with the possible exception of the South, where the European contribution reaches nearly 90%. The results, published by the scientific American Journal of Human Biology by a team of the Catholic University of Brasília, show that, in Brazil, physical indicators such as colour of skin, eyes and hair have little to do with the genetic ancestry of each person, which has been shown in previous studies (regardless of census classification).[35] Ancestry informative single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) can be useful to estimate individual and population biogeographical ancestry. Brazilian population is characterized by a genetic background of three parental populations (European, African, and Brazilian Native Amerindians) with a wide degree and diverse patterns of admixture. In this work we analyzed the information content of 28 ancestry-informative SNPs into multiplexed panels using three parental population sources (African, Amerindian, and European) to infer the genetic admixture in an urban sample of the five Brazilian geopolitical regions. The SNPs assigned apart the parental populations from each other and thus can be applied for ancestry estimation in a three hybrid admixed population. Data was used to infer genetic ancestry in Brazilians with an admixture model. Pairwise estimates of F(st) among the five Brazilian geopolitical regions suggested little genetic differentiation only between the South and the remaining regions. Estimates of ancestry results are consistent with the heterogeneous genetic profile of Brazilian population, with a major contribution of European ancestry (0.771) followed by African (0.143) and Amerindian contributions (0.085). The described multiplexed SNP panels can be useful tool for bioanthropological studies but it can be mainly valuable to control for spurious results in genetic association studies in admixed populations."[32]

| Region[32] | European | African | Native American |

|---|---|---|---|

| Northern Brazil | 71.10% | 18.20% | 10.70% |

| Northeast of Brazil | 77.40% | 13.60% | 8.90% |

| West-Central Brazil | 65.90% | 18.70% | 11.80% |

| Southeast Region, Brazil | 79.90% | 14.10% | 6.10% |

| Southern Brazil | 87.70% | 7.70% | 5.20% |

An autosomal DNA study from 2009 found a similar profile "all the Brazilian samples (regions) lie more closely to the European group than to the African populations or to the Mestizos from Mexico."[36]

| Region[36] | European | African | Native American |

|---|---|---|---|

| Northern Brazil | 60.6% | 21.3% | 18.1% |

| Northeast of Brazil | 66.7% | 23.3% | 10.0% |

| West-Central Brazil | 66.3% | 21.7% | 12.0% |

| Southeast Region, Brazil | 60.7% | 32.0% | 7.3% |

| Southern Brazil | 81.5% | 9.3% | 9.2% |

According to another autosomal DNA study from 2008, by the University of Brasília (UnB), European ancestry dominates in the whole of Brazil (in all regions), accounting for 65.90% of heritage of the population, followed by the African contribution (24.80%) and the Native American (9.3%); the European ancestry being the dominant ancestry in all regions including the Northeast of Brazil.[37]

A study from 1965, "Methods of Analysis of a Hybrid Population" (Human Biology, vol 37, number 1), led by the geneticists D. F. Roberts e R. W. Hiorns, found out the average the Northeastern Brazilian to be predominantly European in ancestry (65%), with minor but important African and Native American contributions (25% and 9%).[38]

Religion

Nordeste has the largest percentage of Roman Catholics of any region of the country.

Culture

Nordeste has a rich culture, with its unique constructions in the old centers of Salvador, Recife and Olinda, dance (frevo and maracatu), music (axé and forró) and unique cuisine. Dishes particular to the region include carne de sol, farofa, acarajé, vatapá, paçoca, canjica, pamonha, quibebe, bolo de fubá cozido, sururu de capote and many others. Salvador was the first Brazilian capital.

The festival of São João (Saint John), one of the festas juninas, is especially popular in Nordeste, particularly in Caruaru in the state of Pernambuco and Campina Grande in the state of Paraíba. The festival takes place once a year in June. As Nordeste is mostly arid or semi-arid, the Northeasters give thanks to Saint John for the rainfall that typical falls this time of year, which greatly helps the farmers with their crops. And because this time of year also coincides with the corn harvest many regional dishes containing corn, such as canjica, pamonha, and milho verde, have become part of the cultural tradition.

The Bumba-Meu-Boi festival is also popular, especially in the state of Maranhão. During the Bumba-Meu-Bói festival in the city of São Luis do Maranhão and its environs there are many different groups, with elaborate costumes and different styles of music, which are called sotaques: sotaque de orquestra, as the names implies, uses an orchestra of saxophones, clarinets, flutes, banjos, drums, etc.; sotaque de zabumba employs primarily very large drums; and sotaque de matraca, a percussion instrument made of two pieces of wood that you carry in your hands and hit against each other. Some matracas are very large and are carried around the neck.

Many major cities in Nordeste also hold an off-season carnaval (or "micareta"), such as the Carnatal in Natal or the Fortal in Fortaleza. Since its inception in 1991, Carnatal has become the largest off-season carnaval in Brazil. The event takes place once a year, in December, and draws roughly one million participants. The Fortal takes place once every year as well but in the month of July. Held in a stadium called Cidade Fortal, the Fortal is considered the largest indoor off-season carnaval in Brazil.

Celebrities

The Northeast of Brazil is home to many notable Brazilians, including 6 former presidents:

Arts & Letters

- Paulo Freire, educator and philosopher who was a leading advocate of critical pedagogy;

- Aurélio Buarque de Holanda, author of the most widely Portuguese Dictionary adopted and cited in Brazil;

- Nelson Rodrigues, playwright, author of play Vestido de Noiva (The Wedding Dress)

- Luís da Câmara Cascudo, folklorist

- Jorge Amado, wrote stories of life in state of Bahia

- Zé Ramalho, musician

- José de Alencar, writer from the 19th century,

- Rachel de Queiroz, writer; the first woman to become part of the Academia Brasileira de Letras;

- Ferreira Gullar, poet, one of the founders of Neo-Concrete Movement;

- João Cabral de Melo Neto, writer and poet, whose body of work is a solid reference to the hardships of the local people endures;

- Gonçalves Dias, poet;

- Ariano Suassuna, playwright, which work has been focus of a recent revival, via TV and Cinema adaptations;

- Luiz Gonzaga, musician, author of many successes, including "Asa Branca", with Humberto Teixeira;

- Gilberto Gil, musician

- Alceu Valença, musician

- Djavan, musician

- Raul Seixas, musician

- Caetano Veloso, musician

- Dorival Caymmi, musician

- Sílvio Romero, folklorist

- Graciliano Ramos, writer

- Castro Alves, poet

- Geraldo Vandré, musician during the mid-60's, author of many songs against the then dictatorship imposed in the country.

- Hermeto Pascoal, musician, creator of a revolutionary style and approach to Music, born in Arapiraca, Alagoas;

- Daniela Mercury, musician

- Clarice Lispector, writer

- Aluísio de Azevedo, writer, precursor of modern, urban literature

Science & Math

- Mário Schenberg, physicist, electrical engineer, art critic and writer;

- José Leite Lopes, theoretical physicist in the field of quantum field theory and particle physics;

- Leopoldo Nachbin, mathematician who is best known for Nachbin's theorem;

- Paulo Ribenboim, mathematician;

- Fernando de Mendonça, electronic engineer, founder of Brazil's National Institute for Space Research;

- Casimiro Montenegro Filho, founder of the Instituto Tecnológico de Aeronáutica (ITA);

- Carlos Paz de Araújo, scientist and inventor, he holds nearly 600 patents in the area of nanotechnology;

- Maurício Peixoto, mathematician, he pioneered the studies on structural stability, and he is the author of the Peixoto's theorem;

- Milton Santos, geographer

Medicine

- Pirajá da Silva, physician responsible for the identification of the cycle of the Schistosomiasis;

- Nise da Silveira, Psychiatry that founded the Museum of Images of the Unconscious and introduced Jungian psychology in Brazil;

Business & Economics

- José Ermírio de Moraes, entrepreneur, founder of the Votorantim Group, the Votorantim Group is one of the largest industrial conglomerates in Latin America,

- Norberto Odebrecht, entrepreneur from the Building Industry;

- Assis Chateaubriand, media conglomerate owner, founded the first television network of Latin America

- Celso Furtado, economist, who while in exile was guest teacher in the University of Sorbonne, in Paris, France;

Politics & Law

- Clóvis Beviláqua, jurist, author of the Brazilian Civil Code of 1916;

- Luíza Erundina, first female mayor of São Paulo;

- Pontes de Miranda, jurist;

- Teixeira de Freitas, jurist, author of a Brazilian Civil Code .

- Humberto de Alencar Castelo Branco, former Brazilian president

- Epitácio Pessoa, former Brazilian president

- Floriano Peixoto, former Brazilian president

- Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, former Brazilian president

- José Sarney, former Brazilian president

- Marshal Deodoro da Fonseca, first president of the Brazilian Republic;

Entertainment

- Glauber Rocha, motion picture director, born in Bahia;

- Martha Vasconcellos, Miss Universe in 1968

- Martha Rocha, Miss Brazil

- Adriana Lima, international model

Sports

- Juninho Pernambucano, male footballer, all-time leading scorer from free kicks

- Marta, female football player, five-time FIFA Women's World Player of the Year

- Oscar Schmidt, basketball player; member of the Naismith and FIBA Halls of Fame

Scholars & Educators

- Ruy Barbosa, intellectuals;

- Anísio Teixeira, educator

- Gilberto Freyre, sociologist, author of work about the structure of Brazil's Social Relations, the "Casa Grande & Senzala", a source of the origins of the intrincate Social & Ethnics in the Country;

Spiritual, Religious & Cultural Figures

- Nísia Floresta, pioneer of feminism in Brasil;

- Padre Cícero, spiritual leader of the whole Region, widely worshipped in Nordeste

- Zumbi, a freedom fighter, leader of Brazil's most important Quilombo, the "Quilombo of Palmares";

- Virgulino Ferreira da Silva(Lampião), bandit leader of a Cangaço band of marauders and outlaws, who defied the authorities of Brazilian Northeast in the 1920s and 1930s.

In popular culture

Northeast Brazil and especially Fortaleza are where the espionage hero Cono 7Q grows up in the spy novel Performance Anomalies,[40] by Victor Robert Lee.[41][42]

See also

Notes

- AJU Santa Maria Airport (Sergipe), Aracaju, Sergipe; MCZ Zumbi dos Palmares International Airport, Maceió, Alagoas; PHB Parnaíba-Prefeito Dr. João Silva Filho International Airport Parnaíba, Piauí; SLZ Marechal Cunha Machado International Airport, São Luís, Maranhão; NAT Augusto Severo International Airport, Natal, Rio Grande do Norte; FOR Pinto Martins International Airport, Fortaleza, Ceará; JPA Presidente Castro Pinto International Airport, João Pessoa, Paraíba, REC Guararapes International Airport, Recife, Pernambuco; SSA Deputado Luís Eduardo Magalhães International Airport, Salvador, Bahia

- by the Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE), an agency of the Brazilian federal administration

- The 1988 Brazilian Constitution treats the municipalities as parts of the Federation and not simply dependent subdivisions of the states.

References

- Garmany, Jeff (2011). "Situating Fortaleza: Urban space and uneven development in northeastern Brazil". Cities. Elsevier. 28 (1): 45–52. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2010.08.004.

- Ranking das maiores regiões metropolitanas do Brasil

- Brito SSB, Cunha APMA, Cunningham CC, Alvala RC, Marengo JA, Carvalho MA. 2018. Frequency, duration, and severity of drought in the Semiarid Northeast Brazil region. Int J Climatol 38 (2): 517-519.

- Lemos, C. M. (2007). Drought, Governance and Adaptive Capacity in North East Brazil: A Case Study of Ceará. Human Development Report. Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/9fc9/b6ee36d7992252784771e039b1757e9cd7db.pdf

- Marengo, JA; Bernasconi, M (2014). ""Regional differences in aridity/drought conditions over Northeast brazil" present state and future projections". Climatic Change. 129 (1): 103–105. doi:10.1007/s10584-014-1310-1.

- Métraux, A. (1927). "Migrations historiques des Tupi-Guarani". Journal de la Société des américainistes. 19. JSTOR 24719658.

- Campbell, Lyle; Grondona, Verónica (2012). The Indigenous Languages of South America: A Comprehensive Guide (illustrated ed.). Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9783110258035. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- Williams, Caroline A. (2013). Bridging the Early Modern Atlantic World: People, Products, and Practices on the Move. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 117. ISBN 9781409480372. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- Campbell, Thomas J. (1921). The Jesuits, 1534–1921: A History of the Society of Jesus from Its Foundation to the Present Time. New York: The Encyclopedia Press. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- Meuwese, Marcus P. (2003). "For the Peace and Well-Being of the Country": Intercultural Mediators and Dutch-Indian Relations in New Netherland and Dutch Brazil, 1600-1664 (Thesis). University Of Notre Dame. p. 184. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- Williams, Caroline A. (2013). Bridging the Early Modern Atlantic World: People, Products, and Practices on the Move. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 17. ISBN 9781409480372. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- Maxwell, Kenneth (2001). "The Spark: Pombal, the Amazon and the Jesuits". Portuguese Studies. 17: 175. JSTOR 41105166.

- Graden, Dale T. (1996). "An Act "Even of Public Security": Slave Resistance, Social Tensions, and the End of the International Slave Trade to Brazil, 1835-1856" (PDF). Hispanic American Historical Review. 76 (2): 240. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 April 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- Paulo Gil Soares, in Vida, paix~ao e mortes de Corisco, o Diabo Louro

- Produto Interno Bruto - PIB e participação das Grandes Regiões e Unidades da Federação - 2014

- "Brazil: Metropolitan Areas". citypopulation.de. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- Ceará retoma o posto de 4º maior produtor têxtil nacional | Profissão Moda. O seu portal de moda Archived 2011-08-22 at the Wayback Machine

- Polo Industrial de Camaçari Archived 2016-03-12 at the Wayback Machine

- "Indústria da Seca".

- Exploring Brazil's Northeast

- ImoveisNordeste.com

- REDAÇÃO. "Portos e Navios - Cresce a movimentação de grãos no Centro-Norte; VLI já movimentou mais de cinco milhões de toneladas este ano" (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 2018-02-13. Retrieved 2018-05-06.

- "Maranhão é pioneiro na exploração de gás natural | O Imparcial". O Imparcial (in Portuguese). 2017-06-06. Retrieved 2018-05-06.

- Energia, Agência de Notícias Ambiente. "Energia eólica é responsável por 50% do abastecimento do Nordeste". Ambiente Energia (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2018-05-06.

- "Conheça os maiores parques solares do Brasil - Sharenergy". Sharenergy (in Portuguese). 2017-12-20. Retrieved 2018-05-06.

- Robb Larkins, Erika; José Bacelar da Silva, Antonio (11 November 2019). "The Bolsonaro Election, Antiblackness, and Changing Race Relations in Brazil". The Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology. 24 (2). doi:10.1111/jlca.12438. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- Pacheco, Tania (28 October 2008). "Inequality, environmental injustice, and racism in Brazil: beyond the question of colour". Development in Practice. 18 (6): 713–725. doi:10.1080/09614520802386355. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- Da Silva Martins, Sérgio; Alberto Medeiros, Carlos; Larkin Nascimento, Elisa (July 2004). "The Road from "Racial Democracy" to Affirmative Action in Brazil". Journal of Black Studies. 34 (6): 7878–816. doi:10.1177/0021934704264006. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- Salles, Ygor (7 October 2018). "Após primeiro turno, nordestinos são alvos de preconceito mais uma vez". Folha de São Paulo. Archived from the original on 25 January 2019. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- Rodrigues De Moura, Ronald; Coelho, Antonio Victor Campos; De Queiroz Balbino, Valdir; Crovella, Sergio; Brandão, Lucas André Cavalcanti (2015). "Meta-analysis of Brazilian genetic admixture and comparison with other Latin America countries". American Journal of Human Biology. 27 (5): 674–680. doi:10.1002/ajhb.22714. PMID 25820814.

- Saloum De Neves Manta, Fernanda; Pereira, Rui; Vianna, Romulo; Rodolfo Beuttenmüller De Araújo, Alfredo; Leite Góes Gitaí, Daniel; Aparecida Da Silva, Dayse; De Vargas Wolfgramm, Eldamária; Da Mota Pontes, Isabel; Ivan Aguiar, José; Ozório Moraes, Milton; Fagundes De Carvalho, Elizeu; Gusmão, Leonor (2013). "Revisiting the Genetic Ancestry of Brazilians Using Autosomal AIM-Indels". PLOS ONE. 8 (9): e75145. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...875145S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0075145. PMC 3779230. PMID 24073242.

- Lins, T. C.; Vieira, R. G.; Abreu, B. S.; Grattapaglia, D.; Pereira, R. W. (March–April 2009). "Genetic composition of Brazilian population samples based on a set of twenty-eight ancestry informative SNPs". American Journal of Human Biology. 22 (2): 187–192. doi:10.1002/ajhb.20976. PMID 19639555.

- Pena, Sérgio D. J.; Di Pietro, Giuliano; Fuchshuber-Moraes, Mateus; Genro, Julia Pasqualini; Hutz, Mara H.; Kehdy, Fernanda de Souza Gomes; Kohlrausch, Fabiana; Magno, Luiz Alexandre Viana; Montenegro, Raquel Carvalho; Moraes, Manoel Odorico; de Moraes, Maria Elisabete Amaral; de Moraes, Milene Raiol; Ojopi, Élida B.; Perini, Jamila A.; Racciopi, Clarice; Ribeiro-dos-Santos, Ândrea Kely Campos; Rios-Santos, Fabrício; Romano-Silva, Marco A.; Sortica, Vinicius A.; Suarez-Kurtz, Guilherme (2011). Harpending, Henry (ed.). "The Genomic Ancestry of Individuals from Different Geographical Regions of Brazil is More Uniform Than Expected". PLoS ONE. 6 (2): e17063. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...617063P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017063. PMC 3040205. PMID 21359226.

- Nossa herança europeia — Archived 2011-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- DNA de brasileiro é 80% europeu, indica estudo

- Forensic Science International: Genetics. Allele frequencies of 15 STRs in a representative sample of the Brazilian population (inglés) Archived 2011-04-08 at WebCite basandos en estudios del IBGE de 2008. Se presentaron muestras de 12.886 individuos de distintas etnias, por regiones, provenían en un 8,26% del Norte, 23,86% del Nordeste, 4,79% del Centro-Oeste, 10,32% del Sudeste y 52,77% del Sur.

- the impact of migrations in the constitution of Latin American populations

- BVGF - A Obra / OpЩsculos Archived 2002-04-23 at the Wayback Machine

- http://www.bibliotecadigital.ufmg.br/dspace/bitstream/1843/BUOS-8FMH5A/1/entre_fanaticos_e_her_is___gabriel_braga.pdf

- Lee, Victor Robert (2012-08-29). Performance Anomalies. Mercury Frontline LLC. ISBN 9781938409219.

- Diplomat, James Pach, The. "Interview: Victor Robert Lee". The Diplomat. Retrieved 2017-06-08.

- Performance Anomalies

- Ferretti, F (2019). "Decolonising the Northeast: subalterns, non-European heritages and radical geography in Pernambuco". Annals of the American Association of Geographers. 109: 1632–1650. doi:10.1080/24694452.2018.1554423.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Brazil Northeast. |

- Brazilian Tourism Portal

- Photos of the Northeast Region of Brazil

- discover Bahia in your language with expats

.jpg)