Pedro I of Brazil

Dom Pedro I (English: Peter I; 12 October 1798 – 24 September 1834), nicknamed "the Liberator", was the founder and first ruler of the Empire of Brazil. As King Dom Pedro IV, he reigned briefly over Portugal, where he also became known as "the Liberator" as well as "the Soldier King".[upper-alpha 1] Born in Lisbon, Pedro I was the fourth child of King Dom João VI of Portugal and Queen Carlota Joaquina, and thus a member of the House of Braganza. When the country was invaded by French troops in 1807, he and his family fled to Portugal's largest and wealthiest colony, Brazil.

| Pedro I of Brazil Pedro IV of Portugal | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Emperor Dom Pedro I at age 35, 1834 | |||||

| Emperor of Brazil | |||||

| Reign | 12 October 1822 – 7 April 1831 | ||||

| Coronation | 1 December 1822 Imperial Chapel | ||||

| Successor | Pedro II | ||||

| King of Portugal | |||||

| Reign | 10 March 1826 – 2 May 1826 | ||||

| Predecessor | João VI | ||||

| Successor | Maria II | ||||

| Born | 12 October 1798 Queluz Palace, Lisbon, Portugal | ||||

| Died | 24 September 1834 (aged 35) Queluz Palace, Lisbon, Portugal | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue among others... | |||||

| |||||

| House | Braganza | ||||

| Father | João VI of Portugal | ||||

| Mother | Carlota Joaquina of Spain | ||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | ||||

| Signature | |||||

The outbreak of the Liberal Revolution of 1820 in Lisbon compelled Pedro I's father to return to Portugal in April 1821, leaving him to rule Brazil as regent. He had to deal with threats from revolutionaries and insubordination by Portuguese troops, all of which he subdued. The Portuguese government's threat to revoke the political autonomy that Brazil had enjoyed since 1808 was met with widespread discontent in Brazil. Pedro I chose the Brazilian side and declared Brazil's independence from Portugal on 7 September 1822. On 12 October, he was acclaimed Brazilian emperor and by March 1824 had defeated all armies loyal to Portugal. A few months later, Pedro I crushed the short-lived Confederation of the Equator, a failed secession attempt by provincial rebels in Brazil's northeast.

A secessionist rebellion in the southern province of Cisplatina in early 1825, and the subsequent attempt by the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata to annex it, led the Empire into the Cisplatine War. In March 1826, Pedro I briefly became king of Portugal before abdicating in favor of his eldest daughter, Dona Maria II. The situation worsened in 1828 when the war in the south resulted in Brazil's loss of Cisplatina. During the same year in Lisbon, Maria II's throne was usurped by Prince Dom Miguel, Pedro I's younger brother. The Emperor's concurrent and scandalous sexual affair with a female courtier tarnished his reputation. Other difficulties arose in the Brazilian parliament, where a struggle over whether the government would be chosen by the monarch or by the legislature dominated political debates from 1826 to 1831. Unable to deal with problems in both Brazil and Portugal simultaneously, on 7 April 1831 Pedro I abdicated in favor of his son Dom Pedro II, and sailed for Europe.

Pedro I invaded Portugal at the head of an army in July 1832. Faced at first with what seemed a national civil war, he soon became involved in a wider conflict that enveloped the Iberian Peninsula in a struggle between proponents of liberalism and those seeking a return to absolutism. Pedro I died of tuberculosis on 24 September 1834, just a few months after he and the liberals had emerged victorious. He was hailed by both contemporaries and posterity as a key figure who helped spread the liberal ideals that allowed Brazil and Portugal to move from absolutist regimes to representative forms of government.

Early years

Birth

Pedro was born at 08:00 on 12 October 1798 in the Queluz Royal Palace near Lisbon, Portugal.[1] He was named after St. Peter of Alcantara, and his full name was Pedro de Alcântara Francisco António João Carlos Xavier de Paula Miguel Rafael Joaquim José Gonzaga Pascoal Cipriano Serafim.[2][3] He was referred to using the honorific "Dom" (Lord) from birth.[4]

Through his father, Prince Dom João (later King Dom João VI), Pedro was a member of the House of Braganza (Portuguese: Bragança) and a grandson of King Dom Pedro III and Queen Dona (Lady) Maria I of Portugal, who were uncle and niece as well as husband and wife.[5][6] His mother, Doña Carlota Joaquina, was the daughter of King Don Carlos IV of Spain.[7] Pedro's parents had an unhappy marriage. Carlota Joaquina was an ambitious woman, who always sought to advance Spain's interests, even to the detriment of Portugal's. Reputedly unfaithful to her husband, she went as far as to plot his overthrow in league with dissatisfied Portuguese nobles.[8][9]

As the second eldest son (though the fourth child), Pedro became his father's heir apparent and Prince of Beira upon the death of his elder brother Francisco António in 1801.[10] Prince Dom João had been acting as regent on behalf of his mother, Queen Maria I, after she was declared incurably insane in 1792.[11][12] By 1802, Pedro's parents were estranged; João lived in the Mafra National Palace and Carlota Joaquina in Ramalhão Palace.[13][14] Pedro and his siblings resided in the Queluz Palace with their grandmother Maria I, far from their parents, whom they saw only during state occasions at Queluz.[13][14]

Education

In late November 1807, when Pedro was nine, the royal family escaped from Portugal as an invading French army sent by Napoleon approached Lisbon. Pedro and his family arrived in Rio de Janeiro, then capital of Brazil, Portugal's largest and wealthiest colony, in March 1808.[15] During the voyage, Pedro read Virgil's Aeneid and conversed with the ship's crew, picking up navigational skills.[16][17] In Brazil, after a brief stay in the City Palace, Pedro settled with his younger brother Miguel and their father in the Palace of São Cristóvão (Saint Christopher).[18] Although never on intimate terms with his father, Pedro loved him and resented the constant humiliation his father suffered at the hands of Carlota Joaquina due to her extramarital affairs.[13][19] As an adult, Pedro would openly call his mother, for whom he held only feelings of contempt, a "bitch".[20] The early experiences of betrayal, coldness and neglect had a great impact on the formation of Pedro's character.[13]

A modicum of stability during his childhood was provided by his aia (governess), Maria Genoveva do Rêgo e Matos, whom he loved as a mother, and by his aio (supervisor) friar António de Arrábida, who became his mentor.[21][22] Both were in charge of Pedro's upbringing and attempted to furnish him with a suitable education. His instruction encompassed a broad array of subjects that included mathematics, political economy, logic, history and geography.[23] He learned to speak and write not only in Portuguese, but also Latin and French.[24] He could translate from English and understood German.[25] Even later on, as an emperor, Pedro would devote at least two hours of each day to study and reading.[25][26]

Despite the breadth of Pedro's instruction, his education proved lacking. Historian Otávio Tarquínio de Sousa said that Pedro "was without a shadow of doubt intelligent, quick-witted, [and] perspicacious."[27] However, historian Roderick J. Barman relates that he was by nature "too ebullient, too erratic, and too emotional". He remained impulsive and never learned to exercise self-control or to assess the consequences of his decisions and adapt his outlook to changes in situations.[28] His father never allowed anyone to discipline him.[23] While Pedro's schedule dictated two hours of study each day, he sometimes circumvented the routine by dismissing his instructors in favor of activities that he found more interesting.[23]

First marriage

The prince found fulfillment in activities that required physical skills, rather than in the classroom. At his father's Santa Cruz farm, Pedro trained unbroken horses, and became a fine horseman and an excellent farrier.[29][30] He and his brother Miguel enjoyed mounted hunts over unfamiliar ground, through forests, and even at night or in inclement weather.[29] He displayed a talent for drawing and handicrafts, applying himself to wood carving and furniture making.[31] In addition, he had a taste for music, and under the guidance of Marcos Portugal the prince became an able composer. He had a good singing voice, and was proficient with several musical instruments (including piano, flute and guitar), playing popular songs and dances.[32] Pedro was a simple man, both in habits and in dealing with others. Except on solemn occasions when he donned court dress, his daily attire consisted of white cotton trousers, striped cotton jacket and a broad-brimmed straw hat, or a frock coat and a top hat in more formal situations.[33] He would frequently take time to engage in conversation with people on the street, noting their concerns.[34]

Pedro's character was marked by an energetic drive that bordered on hyperactivity. He was impetuous with a tendency to be domineering and short-tempered. Easily bored or distracted, in his personal life he entertained himself with dalliances with women in addition to his hunting and equestrian activities.[35] His restless spirit compelled him to search for adventure, and, sometimes in disguise as a traveler, he frequented taverns in Rio de Janeiro's disreputable districts.[36][37] He rarely drank alcohol, but was an incorrigible womanizer.[38][39] His earliest known lasting affair was with a French dancer called Noémi Thierry, who had a stillborn child by him. Pedro's father, who had ascended the throne as João VI, sent Thierry away to avoid jeopardizing the prince's betrothal to Archduchess Maria Leopoldina, daughter of Emperor Franz I of Austria (formerly Franz II, Holy Roman Emperor).[40][41]

On 13 May 1817, Pedro was married by proxy to Maria Leopoldina.[42][43] When she arrived in Rio de Janeiro on 5 November, she immediately fell in love with Pedro, who was far more charming and attractive than she had been led to expect. After "years under a tropical sun, his complexion was still light, his cheeks rosy." The 19-year-old prince was handsome and a little above average in height, with bright dark eyes and dark brown hair.[29] "His good appearance", said historian Neill Macaulay, "owed much to his bearing, proud and erect even at an awkward age, and his grooming, which was impeccable. Habitually neat and clean, he had taken to the Brazilian custom of bathing often."[29] The Nuptial Mass, with the ratification of the vows previously taken by proxy, occurred the following day.[44] Seven children resulted from this marriage: Maria (later Queen Dona Maria II of Portugal), Miguel, João, Januária, Paula, Francisca and Pedro (later Emperor Dom Pedro II of Brazil).[45]

Independence of Brazil

Liberal Revolution of 1820

On 17 October 1820, news arrived that the military garrisons in Portugal had mutinied, leading to what became known as the Liberal Revolution of 1820. The military formed a provisional government, supplanting the regency appointed by João VI, and summoned the Cortes—the centuries-old Portuguese parliament, this time democratically elected with the aim of creating a national Constitution.[46] Pedro was surprised when his father not only asked for his advice, but also decided to send him to Portugal to rule as regent on his behalf and to placate the revolutionaries.[47] The prince was never educated to rule and had previously been allowed no participation in state affairs. The role that was his by birthright was instead filled by his elder sister Dona Maria Teresa: João VI had relied on her for advice, and it was she who had been given membership in the Council of State.[48]

Pedro was regarded with suspicion by his father and by the king's close advisers, all of whom clung to the principles of absolute monarchy. By contrast, the prince was a well-known, staunch supporter of liberalism and of constitutional representative monarchy. He had read the works of Voltaire, Benjamin Constant, Gaetano Filangieri and Edmund Burke.[49] Even his wife Maria Leopoldina remarked, "My husband, God help us, loves the new ideas."[50][51] João VI postponed Pedro's departure for as long as possible, fearing that once he was in Portugal, he would be acclaimed king by the revolutionaries.[47]

On 26 February 1821, Portuguese troops stationed in Rio de Janeiro mutinied. Neither João VI nor his government made any move against the mutinous units. Pedro decided to act on his own and rode to meet the rebels. He negotiated with them and convinced his father to accept their demands, which included naming a new cabinet and making an oath of obedience to the forthcoming Portuguese Constitution.[52] On 21 April, the parish electors of Rio de Janeiro met at the Merchants' Exchange to elect their representatives to the Cortes. A small group of agitators seized the meeting and formed a revolutionary government. Again, João VI and his ministers remained passive, and the monarch was about to accept the revolutionaries' demands when Pedro took the initiative and sent army troops to re-establish order.[53] Under pressure from the Cortes, João VI and his family departed for Portugal on 26 April, leaving behind Pedro and Maria Leopoldina.[54] Two days before he embarked, the King warned his son: "Pedro, if Brazil breaks away, let it rather do so for you, who will respect me, than for one of those adventurers."[55]

Independence or Death

At the outset of his regency, Pedro promulgated decrees that guaranteed personal and property rights. He also reduced government expenditure and taxes.[51][56] Even the revolutionaries arrested in the Merchants' Exchange incident were set free.[57] On 5 June 1821, army troops under Portuguese lieutenant general Jorge Avilez (later Count of Avilez) mutinied, demanding that Pedro should take an oath to uphold the Portuguese Constitution after it was enacted. The prince rode out alone to intervene with the mutineers. He calmly and resourcefully negotiated, winning the respect of the troops and succeeding in reducing the impact of their more unacceptable demands.[58][59] The mutiny was a thinly veiled military coup d'état that sought to turn Pedro into a mere figurehead and transfer power to Avilez.[60] The prince accepted the unsatisfactory outcome, but he also warned that it was the last time he would yield under pressure.[59][61]

The continuing crisis reached a point of no return when the Cortes dissolved the central government in Rio de Janeiro and ordered Pedro's return.[62][63] This was perceived by Brazilians as an attempt to subordinate their country again to Portugal—Brazil had not been a colony since 1815 and had the status of a kingdom.[64][65] On 9 January 1822, Pedro was presented with a petition containing 8,000 signatures that begged him not to leave.[66][67] He replied, "Since it is for the good of all and the general happiness of the Nation, I am willing. Tell the people that I am staying."[68] Avilez again mutinied and tried to force Pedro's return to Portugal. This time the prince fought back, rallying the Brazilian troops (which had not joined the Portuguese in previous mutinies),[69] militia units and armed civilians.[70][71] Outnumbered, Avilez surrendered and was expelled from Brazil along with his troops.[72][73]

During the next few months, Pedro attempted to maintain a semblance of unity with Portugal, but the final rupture was impending. Aided by an able minister, José Bonifácio de Andrada, he searched for support outside Rio de Janeiro. The prince traveled to Minas Gerais in April and on to São Paulo in August. He was welcomed warmly in both Brazilian provinces, and the visits reinforced his authority.[74][75] While returning from São Paulo, he received news sent on 7 September that the Cortes would not accept self-governance in Brazil and would punish all who disobeyed its orders.[76] "Never one to eschew the most dramatic action on the immediate impulse", said Barman about the prince, he "required no more time for decision than the reading of the letters demanded."[77] Pedro mounted his bay mare[upper-alpha 2] and, in front of his entourage and his Guard of Honor, said: "Friends, the Portuguese Cortes wished to enslave and persecute us. As of today our bonds are ended. By my blood, by my honor, by my God, I swear to bring about the independence of Brazil. Brazilians, let our watchword from this day forth be 'Independence or Death!'"[78]

Constitutional Emperor

.png)

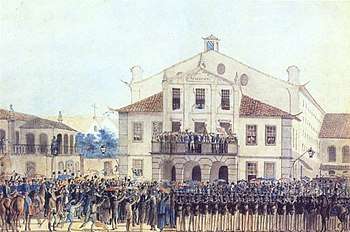

The prince was acclaimed Emperor Dom Pedro I on his 24th birthday, which coincided with the inauguration of the Empire of Brazil on 12 October. He was crowned on 1 December in what is today known as the Old Cathedral of Rio de Janeiro. His ascendancy did not immediately extend throughout Brazil's territories. He had to force the submission of several provinces in the northern, northeastern and southern regions, and the last Portuguese holdout units only surrendered in early 1824.[79][80] Meanwhile, Pedro I's relationship with Bonifácio deteriorated.[81] The situation came to a head when Pedro I, on the grounds of inappropriate conduct, dismissed Bonifácio. Bonifácio had used his position to harass, prosecute, arrest and even exile his political enemies.[82] For months Bonifácio's enemies had worked to win over the Emperor. While Pedro I was still Prince Regent, they had given him the title "Perpetual Defender of Brazil" on 13 May 1822.[83] They also inducted him into Freemasonry on 2 August and later made him grand master on 7 October, replacing Bonifácio in that position.[84]

The crisis between the monarch and his former minister was felt immediately within the Constituent and Legislative General Assembly, which had been elected for the purpose of drafting a Constitution.[85] A member of the Constituent Assembly, Bonifácio resorted to demagoguery, alleging the existence of a major Portuguese conspiracy against Brazilian interests—insinuating that Pedro I, who had been born in Portugal, was implicated.[86][87] The Emperor became outraged by the invective directed at the loyalty of citizens who were of Portuguese birth and the hints that he was himself conflicted in his allegiance to Brazil.[88] On 12 November 1823, Pedro I ordered the dissolution of the Constituent Assembly and called for new elections.[89] On the following day, he placed a newly established native Council of State in charge of composing a constitutional draft. Copies of the draft were sent to all town councils, and the vast majority voted in favor of its instant adoption as the Constitution of the Empire.[90]

As a result of the highly centralized State created by the Constitution, rebellious elements in Ceará, Paraíba and Pernambuco attempted to secede from Brazil and unite in what became known as the Confederation of the Equator.[91][92] Pedro I unsuccessfully sought to avoid bloodshed by offering to placate the rebels.[91][93] Angry, he said: "What did the insults from Pernambuco require? Surely a punishment, and such a punishment that it will serve as an example for the future."[91] The rebels were never able to secure control over their provinces, and were easily suppressed. By late 1824, the rebellion was over.[92][94] Sixteen rebels were tried and executed,[94][95] while all others were pardoned by the Emperor.[96]

Crises within and without

Portuguese dynastic affair

After long negotiations, Portugal signed a treaty with Brazil on 29 August 1825 in which it recognized Brazilian independence.[97] Except for the recognition of independence, the treaty provisions were at Brazil's expense, including a demand for reparations to be paid to Portugal, with no other requirements of Portugal. Compensation was to be paid to all Portuguese citizens residing in Brazil for the losses they had experienced, such as properties which had been confiscated. João VI was also given the right to style himself emperor of Brazil.[98] More humiliating was that the treaty implied that independence had been granted as a beneficent act of João VI, rather than having been compelled by the Brazilians through force of arms.[99][100] Even worse, Great Britain was rewarded for its role in advancing the negotiations by the signing of a separate treaty in which its favorable commercial rights were renewed and by the signing of a convention in which Brazil agreed to abolish slave trade with Africa within four years. Both accords were severely harmful to Brazilian economic interests.[101][102]

A few months later, the Emperor received word that his father had died on 10 March 1826, and that he had succeeded his father on the Portuguese throne as King Dom Pedro IV.[103] Aware that a reunion of Brazil and Portugal would be unacceptable to the people of both nations, he hastily abdicated the crown of Portugal on 2 May in favor of his eldest daughter, who became Queen Dona Maria II.[104][105][upper-alpha 3] His abdication was conditional: Portugal was required to accept the Constitution which he had drafted and Maria II was to marry his brother Miguel.[103] Regardless of the abdication, Pedro I continued to act as an absentee king of Portugal and interceded in its diplomatic matters, as well as in internal affairs, such as making appointments.[106] He found it difficult, at the very least, to keep his position as Brazilian emperor separate from his obligations to protect his daughter's interests in Portugal.[106]

Miguel feigned compliance with Pedro I's plans. As soon as he was declared regent in early 1828, and backed by Carlota Joaquina, he abrogated the Constitution and, supported by those Portuguese in favor of absolutism, was acclaimed King Dom Miguel I.[107] As painful as was his beloved brother's betrayal, Pedro I also endured the defection of his surviving sisters, Maria Teresa, Maria Francisca, Isabel Maria and Maria da Assunção, to Miguel I's faction.[108] Only his youngest sister, Ana de Jesus, remained faithful to him, and she later traveled to Rio de Janeiro to be close to him.[109] Consumed by hatred and beginning to believe rumors that Miguel I had murdered their father, Pedro I turned his focus on Portugal and tried in vain to garner international support for Maria II's rights.[110][111]

War and widowhood

Backed by the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata (present-day Argentina), a small band declared Brazil's southernmost province of Cisplatina to be independent in April 1825.[112] The Brazilian government at first perceived the secession attempt as a minor uprising. It took months before a greater threat posed by the involvement of the United Provinces, which expected to annex Cisplatina, caused serious concern. In retaliation, the Empire declared war in December, triggering the Cisplatine War.[113] The Emperor traveled to Bahia province (located in northeastern Brazil) in February 1826, taking along his wife and daughter Maria. The Emperor was warmly welcomed by the inhabitants of Bahia.[114] The trip was planned to generate support for the war-effort.[115]

The imperial entourage included Domitila de Castro (then-Viscountess and later Marchioness of Santos), who had been Pedro I's mistress since their first meeting in 1822. Although he had never been faithful to Maria Leopoldina, he had previously been careful to conceal his sexual escapades with other women.[116] However, his infatuation for his new lover "had become both blatant and limitless", while his wife endured slights and became the object of gossip.[117] Pedro I was increasingly rude and mean toward Maria Leopoldina, left her short of funds, prohibited her from leaving the palace and forced her to endure Domitila's presence as her lady-in-waiting.[118][119] In the meantime, his lover took advantage by advancing her interests, as well as those of her family and friends. Those seeking favors or to promote projects increasingly sought her help, bypassing the normal, legal channels.[120]

On 24 November 1826, Pedro I sailed from Rio de Janeiro to São José in the province of Santa Catarina. From there he rode to Porto Alegre, capital of the province of Rio Grande do Sul, where the main army was stationed.[121] Upon his arrival on 7 December, the Emperor found the military conditions to be much worse than previous reports had led him to expect. He "reacted with his customary energy: he passed a flurry of orders, fired reputed grafters and incompetents, fraternized with the troops, and generally shook up military and civilian administration."[122] He was already on his way back to Rio de Janeiro when he was told that Maria Leopoldina had died following a miscarriage.[123] Unfounded rumors soon spread that purported that she had died after being physically assaulted by Pedro I.[upper-alpha 4] Meanwhile, the war continued on with no conclusion in sight. Pedro I relinquished Cisplatina in August 1828, and the province became the independent nation of Uruguay.[124][125]

Second marriage

After his wife's death, Pedro I realized how miserably he had treated her, and his relationship with Domitila began to crumble. Maria Leopoldina, unlike his mistress, was popular, honest and loved him without expecting anything in return. The Emperor greatly missed her, and even his obsession with Domitila failed to overcome his sense of loss and regret.[126] One day Domitila found him weeping on the floor and embracing a portrait of his deceased wife, whose sad-looking ghost Pedro I claimed to have seen.[127] Later on, the Emperor left the bed he shared with Domitila and shouted: "Get off of me! I know I live an unworthy life of a sovereign. The thought of the Empress does not leave me."[128][129] He did not forget his children, orphaned of their mother, and was observed on more than one occasion holding his son, the young Pedro, in his arms and saying: "Poor boy, you are the most unhappy prince in the world."[130]

At the insistence of Pedro I, Domitila departed from Rio de Janeiro on 27 June 1828.[131] He had resolved to marry again and to become a better person. He even tried to persuade his father-in-law of his sincerity, by claiming in a letter "that all my wickedness is over, that I shall not again fall into those errors into which I have fallen, which I regret and have asked God for forgiveness".[132] Franz I was less than convinced. The Austrian emperor, deeply offended by the conduct his daughter endured, withdrew his support for Brazilian concerns and frustrated Pedro I's Portuguese interests.[133] Because of Pedro I's bad reputation in Europe, owing to his past behavior, princesses from several nations declined his proposals of marriage one after another.[107] His pride thus wounded, he allowed his mistress to return, which she did on 29 April 1829 after having been away nearly a year.[132][134]

However, once he learned that a betrothal had finally been arranged, the Emperor ended his relationship to Domitila. She returned to her native province of São Paulo on 27 August, where she remained.[135] Days earlier, on 2 August, the Emperor had been married by proxy to Amélie of Leuchtenberg.[136][137] He was stunned by her beauty after meeting her in person.[138][139] The vows previously made by proxy were ratified in a Nuptial Mass on 17 October.[140][141] Amélie was kind and loving to his children and provided a much needed sense of normality to both his family and the general public.[142] After Domitila's banishment from court, the vow the Emperor made to alter his behavior proved to be sincere. He had no more affairs and remained faithful to his spouse.[143] In an attempt to mitigate and move beyond other past misdeeds, he made peace with José Bonifácio, his former minister and mentor.[144][145]

Between Portugal and Brazil

Endless crises

Since the days of the Constituent Assembly in 1823, and with renewed vigor in 1826 with the opening of the General Assembly (the Brazilian parliament), there had been an ideological struggle over the balance of powers wielded by the emperor and legislature in governance. On one side were those who shared Pedro I's views, politicians who believed that the monarch should be free to choose ministers, national policies and the direction of government. In opposition were those, then known as the Liberal Party, who believed that cabinets should have the power to set the government's course and should consist of deputies drawn from the majority party who were accountable to the parliament.[146] Strictly speaking, both the party that supported Pedro I's government and the Liberal Party advocated Liberalism, and thus constitutional monarchy.[147]

Regardless of Pedro I's failures as a ruler, he respected the Constitution: he did not tamper with elections or countenance vote rigging, refuse to sign acts ratified by the government, or impose any restrictions on freedom of speech.[148][149] Although within his prerogative, he did not dissolve the Chamber of Deputies and call for new elections when it disagreed with his aims or postpone seating the legislature.[150] Liberal newspapers and pamphlets seized on Pedro I's Portuguese birth in support of both valid accusations (e.g., that much of his energy was directed toward affairs concerning Portugal)[151] and false charges (e.g., that he was involved in plots to suppress the Constitution and to reunite Brazil and Portugal).[152] To the Liberals, the Emperor's Portuguese-born friends who were part of the Imperial court, including Francisco Gomes da Silva who was nicknamed "the Buffoon", were part of these conspiracies and formed a "secret cabinet".[153][154] None of these figures exhibited interest in such issues, and whatever interests they may have shared, there was no palace cabal plotting to abrogate the Constitution or to bring Brazil back under Portugal's control.[155]

Another source of criticism by the Liberals involved Pedro I's abolitionist views.[156] The Emperor had indeed conceived a gradual process for eliminating slavery. However, the constitutional power to enact legislation was in the hands of the Assembly, which was dominated by slave-owning landholders who could thus thwart any attempt at abolition.[157][158] The Emperor opted to try persuasion by moral example, setting up his estate at Santa Cruz as a model by granting land to his freed slaves there.[159][160] Pedro I also professed other advanced ideas. When he declared his intention to remain in Brazil on 9 January 1822 and the populace sought to accord him the honor of unhitching the horses and pulling his carriage themselves, the then-Prince Regent refused. His reply was a simultaneous denunciation of the divine right of kings, of nobility's supposedly superior blood and of racism: "It grieves me to see my fellow humans giving a man tributes appropriate for the divinity, I know that my blood is the same color as that of the Negroes."[161][162]

Abdication

The Emperor's efforts to appease the Liberal Party resulted in very important changes. He supported an 1827 law that established ministerial responsibility.[163] On 19 March 1831, he named a cabinet formed by politicians drawn from the opposition, allowing a greater role for the parliament in the government.[164] Lastly, he offered positions in Europe to Francisco Gomes and another Portuguese-born friend to extinguish rumors of a "secret cabinet".[142][165] To his dismay, his palliative measures did not stop the continuous attacks from the Liberal side upon his government and his foreign birth. Frustrated by their intransigence, he became unwilling to deal with his deteriorating political situation.[142]

Meanwhile, Portuguese exiles campaigned to convince him to give up on Brazil and instead devote his energies to the fight for his daughter's claim to Portugal's crown.[166] According to Roderick J. Barman, "[in] an emergency the Emperor's abilities shone forth—he became cool in nerve, resourceful and steadfast in action. Life as a constitutional monarch, full of tedium, caution, and conciliation, ran against the essence of his character."[167] On the other hand, the historian remarked, he "found in his daughter's case everything that appealed most to his character. By going to Portugal he could champion the oppressed, display his chivalry and self-denial, uphold constitutional rule, and enjoy the freedom of action he craved."[166]

The idea of abdicating and returning to Portugal took root in his mind, and, beginning in early 1829, he talked about it frequently.[168] An opportunity soon appeared to act upon the notion. Radicals within the Liberal Party rallied street gangs to harass the Portuguese community in Rio de Janeiro. On 11 March 1831, in what became known as the "noite das garrafadas" (night of the broken bottles), the Portuguese retaliated and turmoil gripped the streets of the national capital.[169][170] On 5 April, Pedro I fired the Liberal cabinet, which had only been in power since 19 March, for its incompetence in restoring order.[164][171] A large crowd, incited by the radicals, gathered in Rio de Janeiro downtown on the afternoon of 6 April and demanded the immediate restoration of the fallen cabinet.[172] The Emperor's reply was: "I will do everything for the people and nothing [compelled] by the people."[173] Sometime after nightfall, army troops, including his guard, deserted him and joined the protests. Only then did he realize how isolated and detached from Brazilian affairs he had become, and to everyone's surprise, he abdicated at approximately 03:00 on 7 April.[174] Upon delivering the abdication document to a messenger, he said: "Here you have my act of abdication, I'm returning to Europe and leaving a country that I loved very much, and still love."[175][176]

Return to Europe

War of restoration

At dawn on the morning of 7 April, Pedro, his wife, and others, including his daughter Maria II and his sister Ana de Jesus, were taken on board the British warship HMS Warspite. The vessel remained at anchor off Rio de Janeiro, and, on 13 April, the former emperor transferred to and departed for Europe aboard HMS Volage.[178][179] He arrived in Cherbourg-Octeville, France, on 10 June.[180][181] During the next few months, he shuttled between France and Great Britain. He was warmly welcomed, but received no actual support from either government to restore his daughter's throne.[182] Finding himself in an awkward situation because he held no official status in either the Brazilian Imperial House or in the Portuguese Royal House, Pedro assumed the title of Duke of Braganza on 15 June, a position that once had been his as heir to Portugal's crown. Although the title should have belonged to Maria II's heir, which he certainly was not, his claim was met with general recognition.[183][184] On 1 December, his only daughter by Amélie, Maria Amélia, was born in Paris.[185]

He did not forget his children left in Brazil. He wrote poignant letters to each of them, conveying how greatly he missed them and repeatedly asking them to seriously attend to their educations. Shortly before his abdication, Pedro had told his son and successor: "I intend that my brother Miguel and I will be the last badly educated of the Braganza family".[186][187] Charles Napier, a naval commander who fought under Pedro's banner in the 1830s, remarked that "his good qualities were his own; his bad owing to want of education; and no man was more sensible of that defect than himself."[188][189] His letters to Pedro II were often couched in language beyond the boy's reading level, and historians have assumed such passages were chiefly intended as advice that the young monarch might eventually consult upon reaching adulthood.[180][upper-alpha 5]

While in Paris, the Duke of Braganza met and befriended Gilbert du Motier, Marquis of Lafayette, a veteran of the American Revolutionary War who became one of his staunchest supporters.[184][191] With limited funds, Pedro organized a small army composed of Portuguese liberals, like Almeida Garrett and Alexandre Herculano, foreign mercenaries and volunteers such as Lafayette's grandson, Adrien Jules de Lasteyrie.[192] On 25 January 1832, Pedro bade farewell to his family, Lafayette and around two hundred well-wishers. He knelt before Maria II and said: "My lady, here is a Portuguese general who will uphold your rights and restore your crown." In tears, his daughter embraced him.[193] Pedro and his army sailed to the Atlantic archipelago of the Azores, the only Portuguese territory that had remained loyal to his daughter. After a few months of final preparations they embarked for mainland Portugal, entering the city of Porto unopposed on 9 July. His brother's troops moved to encircle the city, beginning a siege that lasted for more than a year.[194]

Death

In early 1833, while besieged in Porto, Pedro received news from Brazil of his daughter Paula's impending death.[upper-alpha 6] Months later, in September, he met with Antônio Carlos de Andrada, a brother of Bonifácio who had come from Brazil. As a representative of the Restorationist Party, Antônio Carlos asked the Duke of Braganza to return to Brazil and rule his former empire as regent during his son's minority. Pedro realized that the Restorationists wanted to use him as a tool to facilitate their own rise to power, and frustrated Antônio Carlos by making several demands, to ascertain whether the Brazilian people, and not merely a faction, truly wanted him back. He insisted that any request to return as regent be constitutionally valid. The people's will would have to be conveyed through their local representatives and his appointment approved by the General Assembly. Only then, and "upon the presentation of a petition to him in Portugal by an official delegation of the Brazilian parliament" would he consider accepting.[195][196]

During the war, the Duke of Braganza mounted cannons, dug trenches, tended the wounded, ate among the rank and file and fought under heavy fire as men next to him were shot or blown to pieces.[197] His cause was nearly lost until he took the risky step of dividing his forces and sending a portion to launch an amphibious attack on southern Portugal. The Algarve region fell to the expedition, which then marched north straight for Lisbon, which capitulated on 24 July.[198] Pedro proceeded to subdue the remainder of the country, but just when the conflict looked to be winding down to a conclusion, his Spanish uncle Don Carlos, who was attempting to seize the crown of his niece Doña Isabel II, intervened. In this wider conflict that engulfed the entire Iberian Peninsula, the First Carlist War, the Duke of Braganza allied with liberal Spanish armies loyal to Isabel II and defeated both Miguel I and Carlos. A peace accord was reached on 26 May 1834.[199][200]

Except for bouts of epilepsy that manifested in seizures every few years, Pedro had always enjoyed robust health.[31][201] The war, however, undermined his constitution and by 1834 he was dying of tuberculosis.[202] He was confined to his bed in Queluz Royal Palace from 10 September.[203][204] Pedro dictated an open letter to the Brazilians, in which he begged that a gradual abolition of slavery be adopted. He warned them: "Slavery is an evil, and an attack against the rights and dignity of the human species, but its consequences are less harmful to those who suffer in captivity than to the Nation whose laws allow slavery. It is a cancer that devours its morality."[205] After a long and painful illness, Pedro died at 14:30 on 24 September 1834.[206] As he had requested, his heart was placed in Porto's Lapa Church and his body was interred in the Royal Pantheon of the House of Braganza.[207][208] The news of his death arrived in Rio de Janeiro on 20 November, but his children were informed only after 2 December.[209] Bonifácio, who had been removed from his position as their guardian, wrote to Pedro II and his sisters: "Dom Pedro did not die. Only ordinary men die, not heroes."[210][211]

Legacy

.jpg)

Upon the death of Pedro I, the then-powerful Restorationist Party vanished overnight.[212] A fair assessment of the former monarch became possible once the threat of his return to power was removed. Evaristo da Veiga, one of his worst critics as well as a leader in the Liberal Party, left a statement which, according to historian Otávio Tarquínio de Sousa, became the prevailing view thereafter:[208] "the former emperor of Brazil was not a prince of ordinary measure ... and Providence has made him a powerful instrument of liberation, both in Brazil and in Portugal. If we [Brazilians] exist as a body in a free Nation, if our land was not ripped apart into small enemy republics, where only anarchy and military spirit predominated, we owe much to the resolution he took in remaining among us, in making the first shout for our Independence." He continued: "Portugal, if it was freed from the darkest and demeaning tyranny ... if it enjoys the benefits brought by representative government to learned peoples, it owes it to D[om]. Pedro de Alcântara, whose fatigues, sufferings and sacrifices for the Portuguese cause has earned him in high degree the tribute of national gratitude."[213][214]

John Armitage, who lived in Brazil during the latter half of Pedro I's reign, remarked that "even the errors of the Monarch have been attended with great benefit through their influence on the affairs of the mother country. Had he governed with more wisdom it would have been well for the land of his adoption, yet, perhaps, unfortunate for humanity." Armitage added that like "the late Emperor of the French, he was also a child of destiny, or rather, an instrument in the hands of an all-seeing and beneficent Providence for the furtherance of great and inscrutable ends. In the old as in the new world he was henceforth fated to become the instrument of further revolutions, and ere the close of his brilliant but ephemeral career in the land of his fathers, to atone amply for the errors and follies of his former life, by his chivalrous and heroic devotion in the cause of civil and religious freedom."[215]

In 1972, on the 150th anniversary of Brazilian independence, Pedro I's remains (though not his heart) were brought to Brazil—as he had requested in his will—accompanied by much fanfare and with honors due to a head of state. His remains were reinterred in the Monument to the Independence of Brazil, along with those of Maria Leopoldina and Amélie, in the city of São Paulo.[207][216] Years later, Neill Macaulay said that "[c]riticism of Dom Pedro was freely expressed and often vehement; it prompted him to abdicate two thrones. His tolerance of public criticism and his willingness to relinquish power set Dom Pedro apart from his absolutist predecessors and from the rulers of today's coercive states, whose lifetime tenure is as secure as that of the kings of old." Macaulay affirmed that "[s]uccessful liberal leaders like Dom Pedro may be honored with an occasional stone or bronze monument, but their portraits, four stories high, do not shape public buildings; their pictures are not borne in parades of hundreds of thousands of uniformed marchers; no '-isms' attach to their names."[217]

Titles and honors

Titles and styles

| Styles of Pedro I, Emperor of Brazil | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | His Imperial Majesty |

| Spoken style | Your Imperial Majesty |

| Royal styles of Pedro IV, King of Portugal | |

|---|---|

.png) | |

| Reference style | His Most Faithful Majesty |

| Spoken style | Your Most Faithful Majesty |

- 12 October 1798 – 11 June 1801: His Highness The Most Serene Infante Dom Pedro, Grand Prior of Crato[105]

- 11 June 1801 – 20 March 1816: His Royal Highness The Prince of Beira[105]

- 20 March 1816 – 9 January 1817: His Royal Highness The Prince of Brazil[105]

- 9 January 1817 – 10 March 1826: His Royal Highness The Prince Royal[105]

- 12 October 1822 – 7 April 1831: His Imperial Majesty The Emperor[105]

- 10 March 1826 – 2 May 1826: His Most Faithful Majesty The King[105]

- 15 June 1831 – 24 September 1834: His Imperial Majesty The Duke of Braganza[183]

As Brazilian emperor his full style and title were: "His Imperial Majesty Dom Pedro I, Constitutional Emperor and Perpetual Defender of Brazil".[218]

As Portuguese king his full style and title were: "His Most Faithful Majesty Dom Pedro IV, King of Portugal and the Algarves, of either side of the sea in Africa, Lord of Guinea and of Conquest, Navigation and Commerce of Ethiopia, Arabia, Persia and India, etc."[219]

Nobility

As heir to the Portuguese crown:[220]

Honors

Emperor Pedro I was Grand Master of the following Brazilian Orders:[221]

- Order of Christ

- Order of Aviz

- Order of Saint James of the Sword

- Order of the Southern Cross

- Order of Pedro I

- Order of the Rose

As King Pedro IV, he was Grand Master of the following Portuguese Orders:[2]

- Order of Christ

- Order of Saint Benedict of Aviz

- Order of Saint James of the Sword

- Order of the Tower and Sword

- Order of the Immaculate Conception of Vila Viçosa

After having abdicated the Portuguese crown:

- Grand Cross of the Portuguese Order of the Tower and of the Sword, of Valor, Loyalty and Merit on 20 September 1834[105]

He was a recipient of the following foreign honors:[222]

- Knight of the Spanish Order of the Golden Fleece

- Grand Cross of the Spanish Order of Charles III

- Grand Cross of the Spanish Order of Isabella the Catholic

- Grand Cross of the French Order of Saint Louis

- Knight of the French Order of the Holy Spirit

- Knight of the French Order of Saint Michael

- Grand Cross of the Austro-Hungarian Order of Saint Stephen

Genealogy

Ancestry

The ancestry of Emperor Pedro I:[223]

| Ancestors of Pedro I of Brazil | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Issue

| Name | Portrait | Lifespan | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| By Maria Leopoldina of Austria (22 January 1797 – 11 December 1826; married by proxy on 13 May 1817) | |||

| Maria II of Portugal |  |

4 April 1819 – 15 November 1853 |

Queen of Portugal from 1826 until 1853. Maria II's first husband, Auguste de Beauharnais, 2nd Duke of Leuchtenberg, died a few months after the marriage. Her second husband was Prince Ferdinand of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, who became King Dom Fernando II after the birth of their first child. She had eleven children from this marriage. Maria II was heir to her brother Pedro II as Princess Imperial until her exclusion from the Brazilian line of succession by law no. 91 of 30 October 1835.[224] |

| Miguel, Prince of Beira | 26 April 1820 | Prince of Beira from birth to his death. | |

| João Carlos, Prince of Beira | 6 March 1821 – 4 February 1822 |

Prince of Beira from birth to his death. | |

| Princess Januária of Brazil |  |

11 March 1822 – 13 March 1901 |

Married Prince Luigi, Count of Aquila, son of Don Francesco I, King of the Two Sicilies. She had four children from this marriage. Officially recognized as an Infanta of Portugal on 4 June 1822,[225] she was later considered excluded from the Portuguese line of succession after Brazil became independent.[226] |

| Princess Paula of Brazil | 17 February 1823 – 16 January 1833 |

She died age 9, probably of meningitis.[227] Born in Brazil after its independence, Paula was excluded from the Portuguese line of succession.[228] | |

| Princess Francisca of Brazil | _by_an_unknown_photographer.jpg) |

2 August 1824 – 27 March 1898 |

Married Prince François, Prince of Joinville, son of Louis Philippe I, King of the French. She had three children from this marriage. Born in Brazil after its independence, Francisca was excluded from the Portuguese line of succession.[229] |

| Pedro II of Brazil |  |

2 December 1825 – 5 December 1891 |

Emperor of Brazil from 1831 until 1889. He was married to Teresa Cristina of the Two Sicilies, daughter of Don Francesco I, King of the Two Sicilies. He had four children from this marriage. Born in Brazil after its independence, Pedro II was excluded from the Portuguese line of succession and did not become King Dom Pedro V of Portugal upon his father's abdication.[211] |

| By Amélie of Leuchtenberg (31 July 1812 – 26 January 1873; married by proxy on 2 August 1829) | |||

| Princess Maria Amélia of Brazil |  |

1 December 1831 – 4 February 1853 |

She lived her entire life in Europe and never visited Brazil. Maria Amélia was betrothed to Archduke Maximilian, later Emperor Don Maximiliano I of Mexico, but died before her marriage. Born years after her father abdicated the Portuguese crown, Maria Amélia was never in the line of succession to the Portuguese throne.[230] |

| By Domitila de Castro, Marchioness of Santos (27 December 1797 – 3 November 1867) | |||

| Isabel Maria de Alcântara Brasileira |  |

23 May 1824 – 3 November 1898 |

She was the only child of Pedro I born out of wedlock who was officially legitimized by him.[231] On 24 May 1826, Isabel Maria was given the title of "Duchess of Goiás", the style of Highness and the right to use the honorific "Dona" (Lady).[231] She was the first person to hold the rank of duke in the Empire of Brazil.[232] These honors did not confer on her the status of Brazilian princess or place her in the line of succession. In his will, Pedro I gave her a share of his estate.[233] She later lost her Brazilian title and honors upon her 17 April 1843 marriage to a foreigner, Ernst Fischler von Treuberg, Count of Treuberg.[234][235] |

| Pedro de Alcântara Brasileiro | 7 December 1825 – 27 December 1825 |

Pedro I seems to have considered giving him the title of "Duke of São Paulo", which was never realized due to the child's early death.[236] | |

| Maria Isabel de Alcântara Brasileira | 13 August 1827 – 25 October 1828 |

Pedro I considered giving her the title of "Duchess of Ceará", the style of Highness and the right to use the honorific "Dona" (Lady).[237] This was never put into effect due to her early death. Nonetheless, it is quite common to see many sources calling her "Duchess of Ceará", even though "there is no record of the registry of her title in official books, which is also not mentioned in papers related to her funeral".[237] | |

| Maria Isabel de Alcântara Brasileira |  |

28 February 1830 – 13 September 1896 |

Countess of Iguaçu through marriage in 1848 to Pedro Caldeira Brant, son of Felisberto Caldeira Brant, Marquis of Barbacena.[236] She was never given any titles by her father due to his marriage to Amélie. However, Pedro I acknowledged her as his daughter in his will, but gave her no share of his estate, except for a request that his widow aid in her education and upbringing.[233] |

| By Maria Benedita, Baroness of Sorocaba (18 December 1792 – 5 March 1857) | |||

| Rodrigo Delfim Pereira |  |

4 November 1823 – 31 January 1891 |

In his will, Pedro I acknowledged him as his son and gave him a share of his estate.[233] Rodrigo Delfim Pereira became a Brazilian diplomat and lived most of his life in Europe.[238] |

| By Henriette Josephine Clemence Saisset | |||

| Pedro de Alcântara Brasileiro | born 28 August 1829 | In his will, Pedro I acknowledged him as his son and gave him a share of his estate.[233] Pedro de Alcântara Brasileiro had a son, a French navy officer, among other descendants.[239] | |

See also

- Hino da Independência and Hino da Carta, both composed by Pedro I.

- Dom Pedro aquamarine, named after the Emperor and his son Pedro II, is the world's largest cut aquamarine gem.

Endnotes

- Pedro I became known as "the Liberator" in Brazil for his role in the country's independence.(Viana 1994, p. 252) He also became known as "the Liberator" in Portugal, as well as "the Soldier King". Both epithets resulted from his part in the war against his brother, Dom Miguel I.(Saraiva 2001, p. 378)

- Of the two eyewitness accounts of 7 September 1822 that mention Prince Dom Pedro's mount, that of Father Belquior Pinheiro de Oliveira on 7 September 1826 and that of Manuel Marcondes de Oliveira e Melo (later Baron of Pindamonhangaba) on 14 April 1862, both say that it was a besta baia (bay beast) (Costa 1972, Vol 295, pp. 74, 80). In a work published in 1853 and based on an interview with another eyewitness, Colonel Antônio Leite Pereira da Gama Lobo, historian Paulo Antônio do Vale said that it was a "zaino" (bay horse) (Costa 1972, Vol 295, pp. 75, 80). The words used, "bay beast" and "bay horse", are at first glance, both similar and confusingly vague. In Portuguese, as in English, a beast is any non-human animal especially a large four-footed mammal. However, formerly in Brazil beast also meant "mare" (a female horse) as may be seen in dictionaries published in 1946 (Freira 1946, p. 1022) and 1968 (Carvalho 1968, p. 158), although this usage has since been discontinued except in Brazil's northeast and northern regions (Houaiss & Villar 2009, p. 281). The use of besta to refer to a mare is still in use in Portugal (Dicionários Editora 1997, p. 205). Thus, the description of a "bay horse" with non-defined sex and "bay beast (mare)" do in fact coincide. Two of Pedro's biographers, Pedro Calmon (Calmon 1975, p. 97) and Neill Macaulay (Macaulay 1986, p. 125) have identified his horse as a bay mare. Pedro, who was an outstanding horseman and making an average of 108 kilometers per day, was able to ride this animal from the city of São Paulo back to the capital of Rio de Janeiro in just five days, leaving his guard and his entourage far behind (Costa 1972, Vol 295, p. 131). Francisco Gomes da Silva, "the Buffoon", the second person to arrive, lagged behind the Prince by some eight hours (Costa 1972, Vol 295, p. 133).

- Pedro I gave up more than just the crowns of Portugal and Brazil. Less known is that he was also offered the crown of Greece in April 1822 (while he was still prince regent) by the Greek government which was embroiled in a fight for national independence. Pedro I declined, and eventually Otto of Bavaria became King of Greece (Costa 1995, pp. 172–173). Pedro I also declined offers of the Spanish crown made in 1826 and 1829 by liberals who rebelled against the absolutist rule of his uncle, Don Fernando VII. The liberals in Portugal and Spain agreed in 1830 to make Pedro I the "Emperor of Iberia". He seems to have declined this offer also, since nothing came of it (Costa 1995, pp. 195–197). Brazilian historian Sérgio Corrêa da Costa and Portuguese historian Antônio Sardinha have argued, however, with little supporting evidence, that one of the inducements which prompted Pedro I to abdicate the Brazilian crown was to dethrone his brother and his uncle and rule the entire Iberian Peninsula as its emperor (Costa 1995, pp. 197, 199).

- Rumors circulated at the time purporting that Pedro I had kicked Maria Leopoldina in the womb during a heated discussion. The quarrel was witnessed by Domitila de Castro and Wenzel Philipp Leopold, Baron von Mareschal. Then serving Maria Leopoldina's father as the Austrian minister in Brazil and thus inclined to reflect her interests, Mareschal was the sole eyewitness who left an account of what actually happened. According to him, the couple had a bitter argument in which they exchanged insults, but there is no mention of physical violence (Rangel 1928, pp. 162–163; Calmon 1975, pp. 14–15; Costa 1995, p. 86). Historians Alberto Rangel (Rangel 1928, p. 163), Pedro Calmon (Calmon 1950, p. 137; Calmon 1975, p. 14), Otávio Tarquínio de Sousa (Sousa 1972, Vol 2, p. 242), Sérgio Corrêa da Costa (Costa 1995, p. 86) and Roderick J. Barman (Barman 1999, p. 17) have rejected the possibility that Pedro I physically harmed his wife and all affirmed that the altercation was limited to harsh language. A later exhumation confirmed that Maria Leopoldina had died of natural causes.(Tavares 2013) As late as 1831, however, aspersions on Pedro's conduct at the time of his wife's death were still being whispered, serving as a lasting reminder of what people actually believed, regardless of the unfounded nature of the allegations (Sousa 1972, Vol 2, p. 242). Barman was categorical when he noted that Maria Leopoldina's death stripped Pedro I of "any remaining aura of sanctity, either at home or abroad" (Barman 1988, p. 147).

- A notable passage in a missive to Pedro II gives an insight into the Duke of Braganza's political philosophy: "The era in which princes were respected solely because they are simply princes has ended; in the century in which we live, in which the peoples are quite well informed of their rights, it is necessary that princes should be and also should know that they are men and not divinities, that for them knowledge and good sense are indispensable so that they are the more quickly loved than respected. The respect of a free people for their ruler ought to be born of the conviction which they hold that their ruler is capable of making them achieve that level of happiness they aspire to; and if such is not the case, unhappy ruler, unhappy people"[190]

- Pedro made two requests to José Bonifácio, his children's guardian: "the first is to keep for me a bit of her beautiful hair; the second is to place her in the convent of Nossa Senhora da Ajuda [Our Lady of Good Aid] and in the same spot where her good mother, my Leopoldina for whom even today I still shed tears of longing, is located ... I ask you as a father, as a pitiful desolate father, to do me a favor and go in person to deposit next to the body of her mother this fruit of her womb and on this occasion pray for one and other" (Santos 2011, p. 29).

References

- See:

- Calmon 1950, p. 14,

- Sousa 1972, Vol 1, pp. 10–11,

- Macaulay 1986, p. 6,

- Lustosa 2006, p. 36.

- Branco 1838, p. XXXVI.

- Calmon 1975, p. 3.

- Barman 1999, p. 424.

- Calmon 1950, pp. 5, 9, 11.

- Sousa 1972, Vol 1, pp. 5, 9–10.

- Calmon 1950, p. 12.

- Sousa 1972, Vol 1, pp. 4, 8, 10, 28.

- Calmon 1950, pp. 12–13.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 6.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 3.

- Sousa 1972, Vol 1, p. 9.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 7.

- Sousa 1972, Vol 1, p. 12.

- See:

- Costa 1972, pp. 12–13,

- Lustosa 2006, p. 43,

- Sousa 1972, Vol 1, pp. 34, 47.

- Sousa 1972, Vol 1, pp. 39,41.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 22.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 29.

- Sousa 1972, Vol 1, pp. 125, 128.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 189.

- Calmon 1950, p. 33.

- Macaulay 1986, pp. 22, 33.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 32.

- See:

- Sousa 1972, Vol 1, p. 116,

- Costa 1995, pp. 99–101,

- Lustosa 2006, p. 70.

- Costa 1995, p. 101.

- Sousa 1972, Vol 1, p. 121.

- Sousa 1972, Vol 2, p. 101.

- Barman 1999, p. 17.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 46.

- Lustosa 2006, p. 58.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 36.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 37.

- See:

- Macaulay 1986, pp. 175, 255

- Sousa 1972, Vol 2, p. 185

- Sousa 1972, Vol 3, p. 121

- Macaulay 1986, p. 177.

- Barman 1988, p. 134.

- Sousa 1972, Vol 1, p. 252.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 51.

- Lustosa 2006, p. 71.

- Sousa 1972, Vol 1, p. 76.

- Sousa 1972, Vol 1, pp. 78–80.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 53.

- Costa 1972, p. 42.

- Calmon 1950, p. 44.

- Sousa 1972, Vol 1, p. 96.

- Calmon 1950, p. 49.

- Barman 1988, p. 64.

- Barman 1988, p. 68.

- Macaulay 1986, pp. 47–48.

- See:

- Sousa 1972, Vol 1, pp. 121–122,

- Costa 1995, p. 101,

- Lustosa 2006, p. 70.

- Sousa 1972, Vol 1, p. 123.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 93.

- See:

- Barman 1988, p. 70,

- Sousa 1972, Vol 1, pp. 158–164,

- Calmon 1950, pp. 59–62,

- Viana 1994, p. 395.

- See:

- Barman 1988, p. 72,

- Sousa 1972, Vol 1, pp. 203–217,

- Calmon 1950, pp. 66–67,

- Viana 1994, p. 396.

- Barman 1988, p. 72.

- See:

- Barman 1988, p. 72,

- Sousa 1972, Vol 1, p. 227,

- Macaulay 1986, p. 86,

- Costa 1972, p. 69.

- Sousa 1972, Vol 1, pp. 232–233.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 96.

- Barman 1988, p. 74.

- Lustosa 2006, p. 114.

- See:

- Barman 1988, p. 74,

- Lustosa 2006, pp. 113–114,

- Calmon 1950, pp. 75–76.

- Sousa 1972, Vol 1, p. 242.

- Sousa 1972, Vol 1, p. 264.

- Barman 1988, p. 81.

- Sousa 1972, Vol 1, pp. 264–265.

- Barman 1988, p. 82.

- Barman 1988, p. 83.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 107.

- See:

- Barman 1988, p. 84,

- Macaulay 1986, p. 107,

- Calmon 1950, p. 82.

- Barman 1988, p. 78.

- Barman 1988, p. 84.

- Macaulay 1986, pp. 109–110.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 116.

- Calmon 1950, p. 85.

- Barman 1988, pp. 90–91, 96.

- Macaulay 1986, pp. 119, 122–123.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 124.

- Barman 1988, p. 96.

- See:

- Barman 1988, p. 96,

- Sousa 1972, Vol 2, p. 31,

- Macaulay 1986, p. 125.

- Viana 1994, pp. 420–422.

- Barman 1988, pp. 104–106.

- See: Sousa 1972, Vol 1, p. 307, Lustosa 2006, p. 139, Barman 1988, p. 110.

- See:

- Macaulay 1986, p. 148,

- Barman 1988, p. 101,

- Sousa 1972, Vol 2, p. 71.

- Barman 1988, p. 92.

- See:

- Macaulay 1986, pp. 121, 129–130,

- Barman 1988, pp. 100, 272,

- Calmon 1950, p. 93.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 120.

- Macaulay 1986, pp. 153–154.

- Barman 1988, p. 116.

- Barman 1988, p. 117.

- See:

- Barman 1988, p. 118,

- Macaulay 1986, p. 157,

- Viana 1994, p. 429.

- See:

- Macaulay 1986, p. 162,

- Lustosa 2006, p. 174,

- Sousa 1972, Vol 2, pp. 166, 168,

- Viana 1994, p. 430,

- Barman 1988, p. 123.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 165.

- Barman 1988, p. 122.

- Barman 1988, p. 121.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 166.

- Barman 1988, p. 278.

- Viana 1994, p. 435.

- See:

- Barman 1988, p. 128,

- Sousa 1972, Vol 2, p. 193,

- Macaulay 1986, p. 184.

- See:

- Barman 1988, pp. 140–141,

- Sousa 1972, Vol 2, pp. 195–197,

- Macaulay 1986, pp. 184–185.

- Barman 1988, p. 140.

- Sousa 1972, Vol 2, p. 195.

- Barman 1988, p. 141.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 186.

- Barman 1988, p. 142.

- Morato 1835, p. 26.

- Branco 1838, p. XXXVII.

- Barman 1988, p. 148.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 226.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 295.

- Macaulay 1986, pp. 255, 295.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 239.

- Barman 1988, pp. 147–148.

- Barman 1988, p. 125.

- Barman 1988, p. 128.

- Sousa 1972, Vol 2, p. 206.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 190.

- Macaulay 1986, pp. 168, 190.

- Barman 1988, p. 146.

- Lustosa 2006, pp. 192, 231, 236.

- Barman 1999, p. 16.

- Barman 1988, p. 136.

- Macaulay 1986, pp. 201–202.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 202.

- See:

- Rangel 1928, pp. 178–179,

- Macaulay 1986, p. 202,

- Costa 1972, pp. 123–124.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 211.

- Barman 1988, p. 151.

- Barman 1999, p. 24.

- See:

- Rangel 1928, p. 193,

- Lustosa 2006, p. 250,

- Costa 1995, p. 88,

- Sousa 1972, Vol 2, p. 260.

- Costa 1995, p. 88.

- Rangel 1928, p. 195.

- Lustosa 2006, p. 250.

- Lustosa 2006, p. 262.

- Lustosa 2006, p. 252.

- Barman 1988, p. 147.

- Sousa 1972, Vol 2, p. 320.

- Sousa 1972, Vol 2, p. 326.

- Costa 1995, p. 94.

- Sousa 1972, Vol 3, p. 8.

- Lustosa 2006, p. 285.

- Sousa 1972, Vol 3, p. 15.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 235.

- Rangel 1928, p. 274.

- Barman 1988, p. 156.

- See:

- Sousa 1972, Vol 3, pp. 10, 16–17,

- Macaulay 1986, pp. 231, 241,

- Costa 1995, p. 94.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 236.

- Lustosa 2006, p. 283.

- See:

- Barman 1988, pp. 114, 131, 134, 137–139, 143–146, 150,

- Needell 2006, pp. 34–35, 39,

- Macaulay 1986, pp. 195, 234.

- See:

- Macaulay 1986, p. 229,

- Needell 2006, p. 42,

- Barman 1988, pp. 136–138.

- Macaulay 1986, pp. x, 193, 195, 219, 229, 221.

- Viana 1994, p. 445.

- Viana 1994, p. 476.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 229.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 244.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 243.

- Calmon 1950, pp. 155–158.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 174.

- Macaulay 1986, pp. 216–217, 246.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 215.

- Lustosa 2006, pp. 129, 131.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 214.

- Lustosa 2006, p. 131.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 108.

- Lustosa 2006, pp. 128–129.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 195.

- Barman 1988, p. 159.

- Sousa 1972, Vol 3, p. 44.

- Barman 1988, p. 157.

- Barman 1988, p. 138.

- See:

- Viana 1966, p. 24,

- Barman 1988, p. 154,

- Sousa 1972, Vol 3, p. 127.

- Macaulay 1986, pp. 246–247.

- Barman 1988, p. 158.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 250.

- See:

- Sousa 1972, Vol 3, p. 108,

- Barman 1988, p. 159,

- Macaulay 1986, p. 251.

- See:

- Barman 1988, p. 159,

- Macaulay 1986, p. 251,

- Sousa 1972, Vol 3, p. 110.

- See:

- Barman 1988, p. 159,

- Calmon 1950, pp. 192–193,

- Macaulay 1986, p. 252.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 252.

- Sousa 1972, Vol 3, p. 114.

- Lustosa 2006, p. 323.

- Macaulay 1986, pp. 254–257.

- Sousa 1972, Vol 3, pp. 117, 119, 142–143.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 257.

- Sousa 1972, Vol 3, pp. 149, 151.

- Macaulay 1986, pp. 257–260, 262.

- Sousa 1972, Vol 3, p. 158.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 259.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 267.

- Barman 1988, p. 281.

- Calmon 1975, p. 36.

- Costa 1995, p. 117.

- Jorge 1972, p. 203.

- See:

- Barman 1999, p. 40,

- Calmon 1950, p. 214,

- Lustosa 2006, p. 318.

- Lustosa 2006, p. 306.

- See:

- Macaulay 1986, pp. 268–269,

- Sousa 1972, Vol 3, pp. 201, 204,

- Costa 1995, pp. 222, 224.

- See:

- Lustosa 2006, p. 320,

- Calmon 1950, p. 207,

- Costa 1995, p. 222.

- See:

- Costa 1972, pp. 174–179,

- Macaulay 1986, pp. 269–271, 274,

- Sousa 1972, Vol 3, pp. 221–223.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 293.

- Sousa 1972, Vol 3, p. 287.

- See:

- Calmon 1950, pp. 222–223,

- Costa 1995, pp. 311–317,

- Macaulay 1986, pp. 276, 280, 282, 292,

- Sousa 1972, Vol 3, pp. 241–244, 247

- Macaulay 1986, p. 290.

- Macaulay 1986, pp. 295, 297–298.

- Sousa 1972, Vol 3, pp. 291, 293–294.

- Lustosa 2006, pp. 72–73.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 302.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 304.

- Sousa 1972, Vol 3, p. 302.

- Jorge 1972, pp. 198–199.

- See:

- Costa 1995, p. 312,

- Macaulay 1986, p. 305,

- Sousa 1972, Vol 3, p. 309.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 305.

- Sousa 1972, Vol 3, p. 309.

- Barman 1999, p. 433.

- Macaulay 1986, p. 299.

- Calmon 1975, p. 81.

- Barman 1988, p. 178.

- Jorge 1972, p. 204.

- Sousa 1972, Vol 3, pp. 309, 312.

- Armitage 1836, Vol 2, pp. 139–140.

- Calmon 1975, p. 900.

- Macaulay 1986, p. x.

- Rodrigues 1863, p. 71.

- Palácio de Queluz 1986, p. 24.

- Branco 1838, p. XXIV.

- Barman 1999, p. 11.

- Branco 1838, pp. XXXVI–XXXVII.

- Barman 1999, p. 8.

- Barman 1999, p. 438.

- Morato 1835, p. 17.

- Morato 1835, pp. 33–34.

- Barman 1999, p. 42.

- Morato 1835, pp. 17–18.

- Morato 1835, pp. 18–19, 34.

- Morato 1835, pp. 31–32, 35–36.

- Sousa 1972, Vol 2, p. 229.

- Viana 1968, p. 204.

- Rangel 1928, p. 447.

- Rodrigues 1975, Vol 4, p. 22.

- Lira 1977, Vol 1, p. 276.

- Viana 1968, p. 206.

- Viana 1968, p. 205.

- Barman 1999, p. 148.

- Besouchet 1993, p. 385.

Bibliography

- Armitage, John (1836). The History of Brazil, from the period of the arrival of the Braganza family in 1808, to the abdication of Don Pedro The First in 1831. 2. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Barman, Roderick J. (1988). Brazil: The Forging of a Nation, 1798–1852. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-1437-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Barman, Roderick J. (1999). Citizen Emperor: Pedro II and the Making of Brazil, 1825–1891. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-3510-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Besouchet, Lídia (1993). Pedro II e o Século XIX (in Portuguese) (2nd ed.). Rio de Janeiro: Nova Fronteira. ISBN 978-85-209-0494-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Branco, João Carlos Feo Cardoso de Castello (1838). Resenha das familias titulares do reino de Portugal: Acompanhada das notícias biográphicas de alguns indivíduos da mesmas famílias (in Portuguese). Lisbon: Imprensa Nacional.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Calmon, Pedro (1950). O Rei Cavaleiro (in Portuguese) (6 ed.). São Paulo: Edição Saraiva.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Calmon, Pedro (1975). História de D. Pedro II (in Portuguese). 1–5. Rio de Janeiro: José Olímpio.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Carvalho, J. Mesquita de (1968). Dicionário prático da língua nacional ilustrado. 1 (12 ed.). São Paulo: Egéria.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Costa, Horácio Rodrigues da (1972). "Os Testemunhos do Grito do Ipiranga". Revista do Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Brasileiro (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: Imprensa Nacional. 295.

- Costa, Sérgio Corrêa da (1972) [1950]. Every Inch a King: A Biography of Dom Pedro I First Emperor of Brazil. Translated by Samuel Putnam. London: Robert Hale. ISBN 978-0-7091-2974-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Costa, Sérgio Corrêa da (1995). As quatro coroas de D. Pedro I. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra. ISBN 978-85-219-0129-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dicionários Editora (1997). Dicionário de Sinônimos (2 ed.). Porto: Porto Editora.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Freira, Laudelino (1946). Grande e novíssimo dicionário da língua portuguesa. 2. Rio de Janeiro: A Noite.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Houaiss, Antônio; Villar, Mauro de Salles (2009). Dicionário Houaiss da língua portuguesa. Rio de Janeiro: Objetiva. ISBN 978-85-7302-963-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jorge, Fernando (1972). Os 150 anos da nossa independendência (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: Mundo Musical.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lustosa, Isabel (2006). D. Pedro I: um herói sem nenhum caráter (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Companhia das Letras. ISBN 978-85-359-0807-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Macaulay, Neill (1986). Dom Pedro: The Struggle for Liberty in Brazil and Portugal, 1798–1834. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-0681-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lima, Manuel de Oliveira (1997). O movimento da Independência (in Portuguese) (6th ed.). Rio de Janeiro: Topbooks.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lira, Heitor (1977). História de Dom Pedro II (1825–1891): Ascenção (1825–1870) (in Portuguese). 1. Belo Horizonte: Itatiaia.

- Morato, Francisco de Aragão (1835). Memória sobre a soccessão da coroa de Portugal, no caso de não haver descendentes de Sua Magestade Fidelíssima a rainha D. Maria II (in Portuguese). Lisbon: Typographia de Firmin Didot.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Needell, Jeffrey D. (2006). The Party of Order: the Conservatives, the State, and Slavery in the Brazilian Monarchy, 1831–1871. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-5369-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rangel, Alberto (1928). Dom Pedro Primeiro e a Marquesa de Santos (in Portuguese) (2 ed.). Tours, Indre-et-Loire: Arrault.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Palácio de Queluz (1986). D. Pedro d'Alcântara de Bragança, 1798–1834 (in Portuguese). Lisbon: Secretária de Estado.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rodrigues, José Carlos (1863). A Constituição política do Império do Brasil (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: Typographia Universal de Laemmert.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rodrigues, José Honório (1975). Independência: revolução e contra-revolução (in Portuguese). 4. Rio de Janeiro: Livraria Francisco Alves Editora.

- Santos, Eugénio Francisco dos (2011). "Fruta fina em casca grossa". Revista de História da Biblioteca Nacional (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: SABIN. 74. ISSN 1808-4001.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Saraiva, António José (2001) [1969]. The Marrano Factory. The Portuguese Inquisition and Its new Christians 1536–1765. Translated by H.P. Solomon and I.S.D. Sasson. Leiden, South Holland: Brill. ISBN 90-04-12080-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sousa, Otávio Tarquínio de (1972). A vida de D. Pedro I (in Portuguese). 1. Rio de Janeiro: José Olímpio.

- Sousa, Otávio Tarquínio de (1972). A vida de D. Pedro I (in Portuguese). 2. Rio de Janeiro: José Olímpio.

- Sousa, Otávio Tarquínio de (1972). A vida de D. Pedro I (in Portuguese). 3. Rio de Janeiro: José Olímpio.

- Tavares, Ingrid (3 April 2013). "Infecção, e não briga, causou aborto e morte de mulher de Dom Pedro 1º" [Infection, and not a fight, caused the abortion and death of the wife of Dom Pedro the First]. UOL. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- Viana, Hélio (1966). D. Pedro I e D. Pedro II. Acréscimos às suas biografias (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Companhia Editora Nacional.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Viana, Hélio (1968). Vultos do Império (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Companhia Editora Nacional.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Viana, Hélio (1994). História do Brasil: período colonial, monarquia e república (in Portuguese) (15th ed.). São Paulo: Melhoramentos. ISBN 978-85-06-01999-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

![]()

Pedro I of Brazil Cadet branch of the House of Aviz Born: 12 October 1798 Died: 24 September 1834 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| New title |

Emperor of Brazil 12 October 1822 – 7 April 1831 |

Succeeded by Pedro II |

| Preceded by João VI |

King of Portugal 10 March 1826 – 2 May 1826 |

Succeeded by Maria II |

.svg.png)

.svg.png)