Vaccine Revolt

The Vaccine Revolt or Vaccine Rebellion (Portuguese: Revolta da Vacina) was a period of civil disorder which occurred in the city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (November 10–18, 1904).

Antecedents

At the beginning of the 20th century the city of Rio de Janeiro, then capital of Brazil, although praised for its beautiful palaces and mansions, suffered from serious inadequacies in basic infrastructure. Such problems included insufficient water and sewer systems, irregular garbage collection, and overcrowded tenements. Many illnesses proliferated in this environment, including tuberculosis, measles, typhus and leprosy. Epidemics of yellow fever, smallpox and bubonic plague occurred on an intermittent basis. Yellow fever was by far the most serious of the three, killing an estimated 60,000 Rio de Janeiro residents between 1850 and 1908. Although periods of respite from this particular disease did transpire as well, they were almost invariably marred by smaller outbreaks of the others.[1] Beginning in 1902, president Rodrigues Alves launched an initiative to sanitize, modernize, and beautify the city. He gave plenary powers to the city's mayor, Pereira Passos, and to Director General of Public Health Dr. Oswaldo Cruz, to execute sweeping improvements in public sanitation.[2]

The mayor initiated an extensive urban reform program, popularly termed the Bota Abaixo ("Break it down"), in reference to the demolition of older buildings and tenement houses, with subsequent conversion of the land to stately avenues, gardens, and upscale homes and businesses. This resulted in the displacement of thousands of poor and working-class people to peripheral neighborhoods, naturally leading them to become resentful of the city government and suspicious of what it might demand of them in the near future.[3] For his part, Dr. Cruz created the Brigadas Mata Mosquitos (Mosquito-Killing Brigades), groups of sanitary service workers who entered homes in order to exterminate the mosquitoes which had been transmitting yellow fever.[4] The campaign also distributed rat poison in order to halt the proliferation of the bubonic plague, and required proper handling, storage, and collection of garbage.

Uprising

To eradicate smallpox, Dr. Cruz convinced the Congress to approve the Mandatory Vaccination Law on October 31, 1904, authorizing sanitary brigade workers, accompanied by police, to enter homes and apply the vaccine by force.[5]

Rio de Janeiro's population was confused and discontented by this time. Many residents had lost their tenement housing to the new developments, while others had had their homes invaded by health workers and police. Articles in the press criticized the action of the government and spoke of possible risks of the vaccine. Moreover, it was rumored that the vaccine would have to be applied to the “intimate parts” of the body (or at least that women would have to undress in order to be vaccinated), stirring further outrage among the conservative underclasses and helping to precipitate the rebellion that followed. Many intellectual contingents within Brazilian society opposed the law as well, including the Positivist Church, medical associations, and much of the National Congress. Although most of these objections stemmed from the practice's perceived infringements upon individual rights, vaccination was still considered a valid subject of debate among the global scientific community at the time.[6]

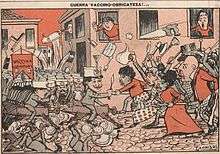

On November 5, the opposition created the Liga Contra a Vacina Obrigatória (League Against Mandatory Vaccination). Formed by a coalition of radical republican politicians, ideological factions within the army, and journalists, this group subsequently began to recruit trade unionists at large gatherings held at the Centro de Classes Operairias. The violence finally began when a few young attendees leaving one of these meetings argued with a police officer, and were promptly arrested. Witnesses to this incident furiously besieged the police station to which the men were taken, and continued to fight with cavalry officers brought in to disperse the excited mob.[7]

From November 10 through 14, Rio de Janeiro descended into violence as each party to the conflict became entrenched in its position. Rioters looted shops, overturned and burned trams, made barricades, pulled out tracks, broke poles and streetlights, and attacked federal troops with rocks, sticks, debris, knives, and stolen guns. Factory laborers revolted in their own workplaces on the outskirts of town, while impoverished and evicted townspeople attempted to secure control over the heart of the city. The momentum of opposition forces reached its zenith on November 14, when cadets of the Escola Militar da Praia Vermelha (Military College of Praia Vermelha) mutinied against President Alves for his rejection of the terms presented to him in a thinly-disguised ultimatum by General Olimpio da Silveira. Silveira's march on the presidential palace was thwarted, however, when his would-be allies at the academy of Realengo were arrested before they could mobilize. In response, the government suspended mandatory vaccination and declared a state of siege. Its forces successfully drove the rebels from their strongholds beginning on November 15, and concluding on November 18 after a grueling period of close-quarter fighting in the predominantly Afro-Brazilian district of Saude.[8] The rebellion was contained, leaving 30 dead and 110 wounded.

Aftermath

Despite its relatively swift downfall, the revolt convinced the mayor and his cabinet to abandon the forced-vaccination program for the time being. This concession was ultimately demonstrated to have been quite superficial, however, as the policy was re-instated several years later. Whatever popular frustrations or progressive ideals that the anti-vaccination movement and its allies might have expressed were thoroughly swept aside with the re-imposition of lawful authority, as the processes of unequal economic development and gentrification continued to accelerate following the uprising. Trade unions were severely marginalized, increasingly dismissed by political elites and middle-class professionals as an unsophisticated reaction against modernization. Moreover, the economic power of these native-born Brazilian workers was further diminished as increasingly large quantities of foreign laborers arrived in Rio de Janeiro on an annual basis. Senator Lauro Sodre, a prominent critic of mandatory vaccination and who had collaborated with Silveira to establish himself as Brazil's new president, subsequently enjoyed a figurehead status among Rodrigues Alves's opposition.[9]

The punishments dealt to participants in the civil conflict varied significantly across political, social, and economic status. Surviving cadets of the 'Escola Militar da Praia Vermelha' were granted amnesty despite committing what amounted to treason, along with Sodre and prominent members of the Positivist Church. The poor rank-and-file of the revolt were much less fortunate, as many hundreds were deported to both the offshore detention facility of the Ilha das Cobras and the frontier region of Acre. Those transported to this distant latter territory were shipped aboard "coastal packet-boats," where it was claimed that they faced egregious conditions comparable to those previously experienced by African slaves en route to the Americas.[10]

Unfortunately for Rio de Janeiro, the city suffered additional smallpox outbreaks following the cessation of the mandatory vaccination program. The final straw which prompted the reversal of even this concession in 1909 was a particularly brutal epidemic the previous year, which killed 9,000 residents.[11] The international medical community at large regarded Cruz's efforts in the affair with considerable sympathy; in 1907, the 14th International Congress on Hygiene and Demography in Berlin awarded him their gold medal. The Federal Serum-Therapeutic Institute, at which Cruz had worked, was also renamed the Oswaldo Cruz Institute in his honor.[12]

See also

- Vaccine controversy

- Revolutions of Brazil

- Vaccine hesitancy

In fiction

- Scliar; Moacyr – "Sonhos Tropicais" (Tropical Dreams) (in Portuguese) Cia das Letras 1992 ISBN 85-7164-249-4

- "Sonhos Tropicais" a 2001 Film adaptation of cited Scliar's book. Synopsis: in english and in Portuguese

Bibliography

- "History of Anti-vaccination Movements". History of Vaccines. The College of Physicians of Philadelphia. Archived from the original on July 29, 2014.

- Hochman Gilberto (2009). "Priority, Invisibility and Eradication: The History of Smallpox and the Brazilian Public Health Agenda". Medical History. 53 (2): 229–52. doi:10.1017/S002572730000020X. PMC 2668879. PMID 19367347.

- Meade Teresa (1986). "'Civilizing Rio de Janeiro': The Public Health Campaign and the Riot of 1904". Journal of Social History. 20 (2): 301–22. doi:10.1353/jsh/20.2.301.

- Meihy; José Carlos & Bertolli Filho; Claudio – "Revolta Da Vacina" (in Portuguese) Ática 1995 ISBN 85-08-05254-5

- Nachman Robert G (1977). "Positivism and Revolution in Brazil's First Republic: The 1904 Revolt". The Americas. 34 (1): 20–39. doi:10.2307/980810.

- Needell Jeffrey D (1987). "The Revolta Contra Vacina of 1904: The Revolt against 'Modernization' in Belle-Époque Rio de Janeiro". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 67 (2): 233–69. doi:10.2307/2515023.

- Sevcenko; Nicolau – ”A Revolta da Vacina” (in Portuguese) Cosac Naify 2010 (1st edition – Brasiliense 1984) ISBN 978-85-7503-868-0

References

- Meade, Teresa (December 1986). ""Civilizing Rio de Janeiro": The Public Health Campaign and the Riot of 1904". Journal of Social History. 20 (2): 306. doi:10.1353/jsh/20.2.301. JSTOR 3787709.

- Nachman, Robert G. (July 1977). "Positivism and Revolution in Brazil's First Republic: The 1904 Revolt". The Americas. 34 (1): 21. doi:10.2307/980810. JSTOR 980810.

- Nachman, Robert G. (July 1977). "Positivism and Revolution in Brazil's First Republic: The 1904 Revolt". The Americas. 34 (1): 22. doi:10.2307/980810. JSTOR 980810.

- Meade, Teresa (December 1986). ""Civilizing Rio de Janeiro": The Public Health Campaign and the Riot of 1904". Journal of Social History. 20 (2): 307–8. doi:10.1353/jsh/20.2.301. JSTOR 3787709.

- Nachman, Robert G. (July 1977). "Positivism and Revolution in Brazil's First Republic: The 1904 Revolt". The Americas. 34 (1): 21. doi:10.2307/980810. JSTOR 980810.

- Needell, Jeffrey D. (May 1987). "The Revolta Contra Vacina of 1904: The Revolt against "Modernization" in Belle-Époque Rio de Janeiro". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 67 (2): 244–58. doi:10.2307/2515023. JSTOR 2515023.

- Needell, Jeffrey D. (May 1987). "The Revolta Contra Vacina of 1904: The Revolt against "Modernization" in Belle-Époque Rio de Janeiro". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 67 (2): 234. doi:10.2307/2515023. JSTOR 2515023.

- Needell, Jeffrey D. (May 1987). "The Revolta Contra Vacina of 1904: The Revolt Against "Modernization" in Belle-Époque Rio de Janeiro". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 67 (2): 234–8. doi:10.2307/2515023. JSTOR 2515023.

- Needell, Jeffrey D. (May 1987). "The Revolta Contra Vacina of 1904: The Revolt Against "Modernization" in Belle-Époque Rio de Janeiro". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 67 (2): 266–8. doi:10.2307/2515023. JSTOR 2515023.

- Needell, Jeffrey D. (May 1987). "The Revolta Contra Vacina of 1904: The Revolt against "Modernization" in Belle-Époque Rio de Janeiro". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 67 (2): 266–9. doi:10.2307/2515023. JSTOR 2515023.

- Meade, Teresa (December 1986). ""Civilizing Rio de Janeiro": The Public Health Campaign and the Riot of 1904". Journal of Social History. 20 (2): 314. doi:10.1353/jsh/20.2.301.

- Hochman, Gilberto (April 2009). "Priority, Invisibility and Eradication: The History of Smallpox and the Brazilian Public Health Agenda". Medical History. 53 (2): 229–52. doi:10.1017/S002572730000020X. PMC 2668879. PMID 19367347.