History of the Jews in Brazil

The history of the Jews in Brazil is a rather long and complex one, as it stretches from the very beginning of the European settlement in the new continent. Although only baptized Christians were subject to the Inquisition, Jews started settling in Brazil when the Inquisition reached Portugal, in the 16th century. They arrived in Brazil during the period of Dutch rule, setting up in Recife the first synagogue in the Americas, the Kahal Zur Israel Synagogue, as early as 1636. Most of those Jews were Sephardic Jews who had fled the Inquisition in Spain and Portugal to the religious freedom of the Netherlands.

Judeus brasileiros יְהוּדִי ברזילאי | |

|---|---|

| Total population | |

| 107,329[1]–120,000[2] Jewish Brazilians | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Brazil: Mainly in the cities of São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro and Porto Alegre. | |

| Languages | |

| Brazilian Portuguese · Hebrew · Yiddish · Ladino | |

| Religion | |

| Judaism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Brazilian people, Sephardi Jews, Mizrahi Jews and Ashkenazi Jews |

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Brazil |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Portuguese Inquisition expanded its scope of operations from Portugal to Portugal's colonial possessions, including Brazil, Cape Verde, and Goa, where it continued investigating and trying cases based on supposed breaches of orthodox Roman Catholicism until 1821. As a colony of Portugal, Brazil was affected by the 300 years of repression of the Portuguese Inquisition, which began in 1536.[3]

In his The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith attributed much of the development of Brazil's sugar industry and cultivation to the arrival of Portuguese Jews who were forced out of Portugal during the Inquisition.[4]

After the first Brazilian constitution in 1824 that granted freedom of religion, Jews began to arrive gradually in Brazil. Many Moroccan Jews arrived in the 19th century, principally because of the rubber boom, settling on the Amazon, where their mixed-race descendants continue to live. Waves of Jewish immigration occurred first by Russian and Polish Jews escaping pogroms and the Russian Revolution, and then during the 1930s during the rise of Nazis in Europe. In the late 1950s, another wave of immigration brought thousands of North African Jews. By the 21st Century the Jewish communities thrive in Brazil. Some anti-Semitic events and acts have occurred, mainly during the 2006 Lebanon War such as vandalism of Jewish cemeteries. But in the main, Brazil's Jewish population is highly educated, with 68% of the community holding university degrees, employed mainly in business, law, medicine, engineering, and the arts. Most own businesses or are self-employed. The IBGE Census shows that 70% of Brazil's Jews belong to the middle and upper classes. As a group, Jews in Brazil see themselves as a successful segment of society, and face relatively little antisemitism at the onset of the 21st Century.[5]

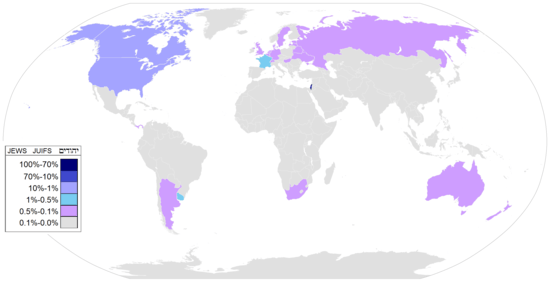

Brazil has the ninth largest Jewish community in the world, about 107,329 by 2010, according to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) Census,[1] and has the second largest Jewish population in South America after Argentina.[6] The Jewish Confederation of Brazil (CONIB) estimates that there are more than 120,000 Jews in Brazil.[2]

First Jewish arrivals

There have been Jews in what is now Brazil since the first Portuguese arrived in the country in 1500, notably Mestre João and Gaspar da Gama who arrived in the first ships. A number of Sephardic Jews immigrated to Brazil during its early settlements. They were known as "New Christians" (Conversos or Marranos — Jews obliged to convert to Roman Catholicism by the Portuguese crown).

The Jews from Portugal avoided immigrating to Brazil, because they would also be persecuted by the Inquisition. Most of the Portuguese Marranos took refuge in Mediterranean countries such as in North Africa, Italy, Greece and the Middle East), and others emigrated to countries that tolerated Judaism, such as the Netherlands, England and Germany. Many Sephardic Jews from Holland and England worked with the maritime trade of the Dutch West India Company, especially with the sugar production in the northeast of Brazil.[7] The first Jews who arrived in North America were Sephardic Jews who after being expelled from Brazil by the Portuguese, settled in the American northeast.

In the final decades of the 18th century, some Marranos came to southeastern Brazil to work in the gold mines. Many were arrested, accused of Judaism. Brazilian families that descend from the Marranos are mainly concentrated in the states of Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro, Pará and Bahia.

Most sources state that the first synagogue of Belém, Sha'ar haShamaim ("Gate of Heaven"), was founded in 1824. There are, however, controversies; Samuel Benchimol, author of Eretz Amazônia: Os Judeus na Amazônia, affirms that the first synagogue in Belém was Eshel Avraham ("Abraham's Tamarisk") and that it was established in 1823 or 1824, while Sha'ar haShamaim was founded in 1826 or 1828.

The Jewish population in the capital of Grão-Pará had by 1842 an established necropolis.[8]

Agricultural settlements

Because of unfavorable conditions in Europe, European Jews began debating in the 1890s about establishing agricultural settlements in Brazil. At first, the plan did not work because of Brazilian political quarrels.[9]

In 1904, the Jewish agricultural colonization, supported by the Jewish Colonization Association, began in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, the southernmost state in Brazil. The main intention of the JCA in creating those colonies was to resettle Russian Jews during the mass immigration from the hostile Russian empire. The first colonies were Philippson (1904) and Quatro Irmãos (1912).[10] However, these colonization attempts all failed because of "inexperience, insufficient funds and poor planning" and also because of "administrative problems, lack of agricultural facilities and the lure of city jobs."

In 1920, the JCA began selling some of the land to non-Jewish settlers.[9] Despite the failure, "The colonies aided Brazil and helped change the stereotypical image of the non-productive Jew, capable of working only in commerce and finance. The main benefit from these agricultural experiments was the removal of restrictions in Brazil on Jewish immigration from Europe during the 20th century."[10]

Other 20th-century developments

By the First World War, about 7,000 Jews were inhabiting Brazil. In 1910 in Porto Alegre, capital of Rio Grande do Sul, a Jewish school was opened and a Yiddish newspaper, Di Menshhayt ("Humanity") was established in 1915. One year later, the Jewish community of Rio de Janeiro formed an aid committee for World War I victims.[9]

Congregação Israelita Paulista (“CIP,” or “Israeli Congregation of São Paulo), the largest synagogue in Brazil, was founded in by Dr. Fritz Pinkus, who was born in Egeln, Germany.[11]

Associação Religiosa Israelita (the “Israeli Religious Association”), now a member of the World Union for Progressive Judaism, was founded by Dr. Heinrich Lemle, who emigrated from Frankfurt to Rio de Janeiro in 1941.[11]

Antisemitism

Auto-da-fé

The first recorded auto-da-fé was held in Paris in 1242. Auto-da-fés took place in France, Spain, Portugal, Brazil, Peru, the Ukraine in the Portuguese colony of Goa, India and in Mexico where the last in the world was held in 1850. Nearly five hundred auto-da-fés were “celebrated” by the Roman Catholic Church over the course of three centuries, and thousands of Jews met their deaths this way usually after months of suffering in the Inquisition's prisons and torture chambers. This brutal and public ritual consisted of a Catholic Mass, a procession of heretics and apostates, many of them marranos, or "secret Jews", and their torture and execution by burning at the stake. Last-minute penitents were garroted to spare the pain of death by burning.[12][13] Auto-da-fé victims were most frequently apostate former Jews and former Muslims, then Alumbrados (followers of a condemned mystical movement) and Protestants, and occasionally those who had been accused of such crimes against the Roman Catholic Church as bigamy and sorcery[14]

Historians note that the best-known action of the Inquisition against Crypto-Jews in Brazil were the Visitations of 1591–93 in Bahia; 1593–95 in Pernambuco; 1618 in Bahia; around 1627 in the Southeast; and in 1763 and 1769 in Grão-Pará, in the north of the country. In the 18th century, the Inquisition was also active in Paraíba, Rio de Janeiro, and Minas Gerais. Approximately 400 "judaizers" were prosecuted, most of them being condemned to imprisonment, and 18 New Christians were condemned to death in Lisbon.

One of the best-known Portuguese playwrights, António José da Silva (1705-1739), "the Jew," who lived part of his life in Portugal and part in Brazil was condemned to death by the Inquisition in 1739.[15] His parents, João Mendes da Silva and Lourença Coutinho, were descended from Jews who had emigrated to the colony of Brazil to escape the Inquisition, but in 1702 that tribunal began to persecute the Marranos or anyone of Jewish descent in Rio, and in October 1712 Lourença Coutinho became a victim. Her husband and children accompanied her to Portugal when António was 7 years old,[16] where she figured among the "reconciled" in the auto-da-fé of July 9, 1713, after undergoing the torment only.[17] António produced his first play or opera in 1733, and the next year he married his cousin, D. Leonor Maria de Carvalho, whose parents had been burnt by the Inquisition, while she herself had gone through an auto-da-fé in Spain and been exiled on account of her religion. They had their first daughter in 1734, but the years of their happiness and of Silva's dramatic career were few, for on October 5, 1737 husband and wife were both imprisoned on the charge of "judaizing." A slave of theirs had denounced them to the Holy Office. Though the details of the accusation against them seemed trivial and contradictory, and some of his friends testified about his Catholic piety and observation, António was condemned to death. On October 18, like those who wanted to die in the Catholic faith, he was first strangled and after had his body burnt in an auto-da-fé.[17] His wife, who witnessed his death, did not long survive him.[18]

Another notable person is Isaac de Castro Tartas (1623-1647) who emigrated to Brazil from France and Holland. In 1641 he arrived in Paraíba, Brazil, where he lived for several years. Against the wishes of his relatives there, he went later to Bahia de Todos os Santos, the colony's capital, where he was recognized as a Jew, arrested by the Portuguese Inquisition, and sent to Lisbon[19] where he died as a Jewish martyr.

20th Century Antisemitism

Heightened antisemitism in Brazil in the 1900s reached its peak during 1933–1945 with the ascent of Nazism in Germany. Brazil blocked its doors to an influx of Jewish refugees from Europe during the Holocaust.[20] Research by Brazil's Virtual Archives on Holocaust and Antisemitism Institute (Arqshoah) has uncovered that between 1937 and 1950 more than 16,000 visas to European Jews attempting to escape the Nazis were denied by the governments of presidents Getulio Vargas and Eurico Gaspar Dutra.[21]

Attitude towards antisemitism

Brazil strictly condemns antisemitism, and such act is an explicit violation of the law. According to Brazilian penal code, it is illegal to write, edit, publish, or sell literature that promotes anti-Semitism or racism.[22] The law provides penalties of up to five years in prison for crimes of racism or religious intolerance and enables courts to fine or imprison for two to five years anyone who displays, distributes, or broadcasts antisemitic or racist material.[23]

In 1989, the Brazilian Congress passed a law prohibiting the manufacture, trade and distribution of swastikas for the purpose of disseminating Nazism. Anyone who violates this law is liable to serve a prison term from between two and five years.[24] (Law no. 7716 of 5 January 1989)

According to a U.S. Department of State report, antisemitism in Brazil remains rare.[23] The results of a global survey on anti-Semitic sentiments, released by the Anti-Defamation League, ranked Brazil among the least anti-Semitic countries in the world. According to this global survey conducted between July 2013 and February 2014, Brazil has the lowest "Anti-Semitic Index" (16%) in Latin America and the third lowest in all Americas, only behind Canada (14%) and the United States (9%).[25][26]

Present-day Jewish community

Brazil has the 9th largest Jewish community in the world, about 107,329 according to the IBGE 2010 Census.[1] The Jewish Confederation of Brazil (CONIB) estimates that there are more than 120,000 Jews in Brazil,[2] with the lower figure representing active practitioners. The current Jewish community is composed by 75% of Ashkenazi Jews of Polish and German descent and also of 25% Sephardic Jews of Spanish, Portuguese, and North African descent; among the North African Jews, a significant number are of Egyptian descent.

Brazilian Jews play an active role in politics, sports, academia, trade and industry, and are overall well integrated in all spheres of Brazilian life. The majority of Brazilian Jews live in the State of São Paulo, but there are also sizeable communities in the States of Rio de Janeiro, Rio Grande do Sul, Minas Gerais, Pernambuco and Paraná.

Jews lead an open religious life in Brazil and there are rarely any reported cases of anti-semitism in the country. In the main urban centers there are schools, associations and synagogues where Brazilian Jews can practice and pass on Jewish culture and traditions. Some Jewish scholars say that the only threat facing Judaism in Brazil is the relatively high frequency of intermarriage, which in 2002 was estimated at 60%. Intermarriage is especially high among the country's Jews and Arabs.[27][28]

There has been a steady stream of aliyah (immigration to Israel) since the nation's foundation in 1948. Between 1948 and 2010, 11,586 Brazilian Jews immigrated to Israel.

Size of Jewish communities in Brazil

- São Paulo, São Paulo: 51,050,[29] 75,000[30]

- Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro: 25,000–30,000[31]

- Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul: 15,000[32]

- Curitiba, Paraná: 1,774[33]

- Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais: 1,714[33]

- Belém, Pará: 900[33]

- Recife, Pernambuco: 700 [33]

- Piracicaba, São Paulo: 700[34]

- Manaus, Amazonas: 627[33]

- Brasília, Distrito Federal: 624[33]

- Niterói, Rio de Janeiro: 600[35]

- Florianópolis, Santa Catarina: 420[36]

- Santos, São Paulo: 413[33]

- Campinas, São Paulo: 364[33]

- Pelotas, Rio Grande do Sul: 330[37]

- Santo André, São Paulo: 311[33]

- Salvador, Bahia: 300[33]* Petrópolis, Rio de Janeiro: 295[33]

- Osasco, São Paulo: 261[33]

- São Bernardo do Campo, São Paulo: 251[33]

- Barueri, São Paulo: 245[33]

- Erechim, Rio Grande do Sul: 240[38]

- Vitória, Espírito Santo: 202[33]

- Goiânia, Goiás: 198[33]

- Nova Friburgo, Rio de Janeiro: 180

- Gurupi, Tocantins: 173[33]

- Santana de Parnaíba, São Paulo: 168[33]

- Cotia, São Paulo: 167[33]

- São Carlos, São Paulo: 150[33]

- Uberaba, Minas Gerais: 143[33]

- Jaboatão dos Guararapes, Pernambuco: 137[33]

- Nilópolis, Rio de Janeiro: 133[33]

- Nova Iguaçu, Rio de Janeiro: 124[33]

- Fortaleza, Ceará: 100–120[39]

- Teresópolis, Rio de Janeiro: 119[33]

- São Gonçalo, Rio de Janeiro: 116[33]

- Campo Grande, Mato Grosso do Sul: 113[33]

- Jandira, São Paulo: 113[33]

- Taboão da Serra, São Paulo: 100[33]

- Rolândia, Paraná: 99[33]

- Aracaju, Sergipe: 96[33]

- Embu-Guaçu, São Paulo: 96[33]

- Natal, Rio Grande do Norte: 91[33]

- Jacareí, São Paulo: 90[33]

- Vitória da Conquista, Bahia: 88[33]

- São Caetano do Sul, São Paulo: 80[33]

- Atibaia, São Paulo: 78[33]

- Franca, São Paulo: 77[33]

- Duque de Caxias, Rio de Janeiro: 75[33]

- Nossa Senhora do Socorro, Sergipe: 75[33]

- Guarulhos, São Paulo: 74[33]

- Ribeirão Preto, São Paulo: ≈70[40]

- Ilhéus, Bahia: 69[33]

- Joinville, Santa Catarina: 68[33]

- Magé, Rio de Janeiro: 67[33]

- Americana, São Paulo: 63[33]

- Blumenau, Santa Catarina: 63[33]

- Londrina, Paraná: 64[33]

- Mairiporã, São Paulo: 64[33]

- Itapira, São Paulo: 63[33]

- Limeira, São Paulo: 63[33]

- Guarujá, São Paulo: 62[33]

- São Sebastião, São Paulo: 60[33]

- Rio das Ostras, Rio de Janeiro: 59[33]

- Volta Redonda, Rio de Janeiro: 59[33]

- Francisco Morato, São Paulo: 58[33]

- São Vicente, São Paulo: 58[33]

- São José dos Campos, São Paulo: 56[33]

- Ourinhos, São Paulo: 55[33]

- Santa Maria, Rio Grande do Sul: 55[33]

- Campina Grande, Paraíba: 54[33]

- Resende, Rio de Janeiro: 54[33]

- Rio Grande, Rio Grande do Sul: 54[33]

- Xaxim, Santa Catarina: 54[33]

- Redenção do Gurguéia, Piauí: 49[33]

- Itajubá, Minas Gerais: 48[33]

- Barra do Bugres, Mato Grosso: 47[33]

- São Joaquim da Barra, São Paulo: 47[33]

- Silvânia, Goiás: 46[33]

- Foz do Iguaçu, Paraná: 45[33]

- Macapá, Amapá: 45[33]

- Araçatuba, São Paulo: 44[33]

- Gravataí, Rio Grande do Sul: 44[33]

- Maracaí, São Paulo: 43[33]

- Passo Fundo, Rio Grande do Sul: 43[33]

- Dourados, Mato Grosso do Sul: 42[33]

- Eldorado do Sul, Rio Grande do Sul: 41[33]

- Luziânia, Goiás: 41[33]

- Rolim de Moura, Rondônia: 41[33]

- Iporã, Paraná: 40[33]

- Juiz de Fora, Minas Gerais: 40[33]

- São Luís, Maranhão: 40[33]

- Paulista, Pernambuco: ≈35

Other smaller Jewish communities include:

- In the state of Pernambuco: Arcoverde, Camaragibe and Olinda

- In the state of Rio de Janeiro: Barra do Piraí, Campos dos Goytacazes, Macaé and São João de Meriti

- In the state of São Paulo: Araçoiaba da Serra, Araraquara, Boituva, Guaratinguetá, Itu, Mauá, Praia Grande, São José do Rio Preto, Taubaté, Ubatuba, Valinhos and Vinhedo

See also

- Amazonian Jews

- Dutch Empire

- Dutch Brazil

- Jewish Agency for Israel

- Kahal Zur Israel Synagogue

- List of Brazilian Jews

- List of Latin American Jews

- Oldest synagogues in the world#Recife, Brazil

- History of the Jews in Latin America

- Brazil–Israel relations

- History of Pernambuco#Jews in Pernambuco

References

- Censo demográfico : 2010 : características gerais da população, religião e pessoas com deficiência [Census 2010: General characteristics of the population, religion and people with disabilities] (PDF) (in Portuguese). Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística [Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics] (IGBE). Tabela 1.4.1 - População residente, por situação do domicílio e sexo, segundo os grupos de religião [Table 1.4.1 - Resident population, by household situation and sex, the religious groups]. ISSN 0104-3145. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- "Brazil". state.gov. US Department of State. Retrieved December 10, 2013.

- JTA Archives. "Impact of Portuguese Inquisition Still Felt by Brazil, Its Jews (last of Three Parts)". www.jta.org. JTA. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- Smith, Adam (1776), The Wealth of Nations (PDF) (Penn State Electronic Classics ed.), republication in 2005 by Pennsylvania State University of The Wealth of Nations, p. 476, archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-20, retrieved 2011-03-08

- Information and text generously provided by Conib – Confederação Israelita do Brasil. "The Jewish Community in Brazil". bh.org.il. Beit Hatfutsot. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- "The Jewish Community of Brazil". The Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot.

- https://www.jta.org/2013/12/26/news-opinion/world/dutch-rabbi-confronts-jews-with-ancestors-complicity-in-slavery

- Scheinbein, Cássia (2006). "Línguas em extinção: o hakitia em Belém do Pará" [Endangered languages: the Hakitia in Belem] (PDF) (in Portuguese). Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. p. 45.

- Oreck, Alden. "Brazil". The Virtual Jewish History Tour. Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 2008-06-09.

- Nachman, Falbel (2007-08-16). "Jewish agricultural settlement in Brazil". Jewish History. Springer Netherlands. 21 (3–4): 325. doi:10.1007/s10835-007-9043-6. OCLC 46840526.

Jewish agricultural colonization in Brazil began in 1904 in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, supported by the Jewish Colonization Association (JCA). The JCA created the first colonies – Philippson (1904) and Quatro Irmãos (1912) – with the intention of resettling Russian Jews during the decisive years of mass immigration from the Russian empire.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) No page; quote taken from abstract. - Rosman, Kitty (October 2012). "The German roots of Brazil's largest synagogues". Jewish Renaissance. 12 (1): 16.

- Bush, Lawrence. "Auto-da-fé". jewishcurrents.org. Jewish Currents. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- Jewish Virtual Library. "Auto De Fe". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- ENCYCLOPÆDIA BRITANNICA. "Auto-da-fé". www.britannica.com. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- Jewish Virtual Library. "Brazil". jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- António José Saraiva: The Marrano Factory: The Portuguese Inquisition and Its New Christians 1536-1765, p. 95

-

- Antonio Jose da Silva, Jewish Virtual Library

- The encyclopedia of Jewish knowledge Jacob de Haas 1946 "CASTRO TARTAS, ISAAC De: Martyr; b. Tartas, Gascony, c.1623: d. Lisbon, 1647. He was arrested by the Inquisition in Bahia dos Santos and sent to Lisbon.

- Ben-Dror, Graciela. "The Catholic Elites in Brazil and Their Attitude Toward the Jews, 1933–1939 (Source: Yad Vashem Studies, XXX, Jerusalem, 2002, pp. 229-270.)". yadvashem.org. Yad Vashem. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- JTA. "Brazil denied 16,000 visas to Jews during Nazi regime — study". timesofisrael.com. Times of Israel. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- "Brazil", International Religious Freedom Report 2010, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, US Department of State, November 17, 2010, retrieved September 7, 2016

- Brazil. US Department of State. Retrieved 2013-12-08.

- Legislation against Antisemitism and Holocaust denial Archived 2013-12-04 at the Wayback Machine. The Coordination Forum For Countering Antisemitism. Retrieved 2013-12-08.

- "Global survey on anti-Semitic sentiments". ADL.org. Anti-Defamation League. Retrieved May 21, 2014.

- Herald Staff (May 14, 2014). "Around 24% of the country holds anti-semitic sentiments". Buenos Aires Herald. Retrieved May 21, 2014.

- Weingarten, Sherwood L. (January 4, 2002). "Brazil's Jews face 60% intermarriage rate". JWeekly.com; J. the Jewish news weekly of Northern California. San Francisco Jewish Community Publications Inc. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- Krieger, Hilary; Stoil, Rebecca (May 4, 2012). "Brazilian FM suggests Arab-Jewish intermarriage is a model for peace". Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- Dashefsky, Arnold; Sheskin, Ira M., eds. (2016), American Jewish Year Book 2015: The Annual Record of the North American Jewish Communities, Springer, p. 319, ISBN 9783319245058

- "Brazil - Modern-Day Community". jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Jewish Virtual Library. 2013. Retrieved 2013-12-22.

- Federação Israelita do Estado do Rio de Janeiro. "Comunidade Judaica do Rio de Janeiro" (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 2010-10-30. Retrieved 2010-10-26.

- "Federação Israelita do Rio Grande do Sul" (in Portuguese). 2009-05-29. Archived from the original on 2009-05-28. Retrieved 2008-06-09.

- Censo Demográfico Brasileiro de 2000. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. 2000.

- Ricci, Daniele (2009-05-29). "Volta para casa: Restos mortais de três judeus deixam Piracicaba". Gazeta de Piracicaba (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2008-06-09.

- Telo da Côrte, Andréa (2009-05-29). "Judeus e Judeus: A Coletividade Judaica de Niterói e as Disputas pela Memória" (PDF) (in Portuguese). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-09. Retrieved 2008-06-09.

- Vainer Schuman, Lia (2009-05-29). "Produção de Sentidos e a Construção da Identidade Judaica em Florianópolis" (PDF) (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2008-06-09.

- Guimarães, Álvaro (2009-05-29). "Perdão e reverência no Sábado dos Sábados" (in Portuguese). Diário Popular. Archived from the original on 2011-08-27. Retrieved 2008-06-09.

- "Prefeitura Municipal de Erechim" (in Portuguese). 2009-05-29. Retrieved 2008-06-09.

- Queirós, Amanda (2007-04-07). "Os judeus do Ceará" (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2010-05-28.

- Toledo, Marcelo (2001-03-11). "Ribeirão Preto terá a 1ª sinagoga da região" (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2010-05-27.

Further reading

- Lesser, Jeffrey (1995). Welcoming the Undesirables: Brazil and the Jewish Question. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-08413-6.

- Pieroni, Geraldo. "Outcasts from the Kingdom: The Inquisition and the Banishment of New Christians to Brazil," in Paolo Bernardini and Norman Fiering, eds. The Jews and the Expansion of Europe to the West, 1450-1800. New York: Berghahn Books 2001, 242–54.

External links

- History of the Jews in Brazil by Ralph G. Bennett