Intertropical Convergence Zone

The Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), known by sailors as the doldrums or the calms because of its monotonous, windless weather, is the area where the northeast and southeast trade winds converge. It encircles Earth near the thermal equator, though its specific position varies seasonally. When it lies near the geographic Equator, it is called the near-equatorial trough. Where the ITCZ is drawn into and merges with a monsoonal circulation, it is sometimes referred to as a monsoon trough, a usage more common in Australia and parts of Asia.

Meteorology

The ITCZ was originally identified from the 1920s to the 1940s as the Intertropical Front (ITF), but after the recognition in the 1940s and the 1950s of the significance of wind field convergence in tropical weather production, the term Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) was then applied.[1]

The ITCZ appears as a band of clouds, usually thunderstorms, that encircle the globe near the Equator. In the Northern Hemisphere, the trade winds move in a southwestward direction from the northeast, while in the Southern Hemisphere, they move northwestward from the southeast. When the ITCZ is positioned north or south of the Equator, these directions change according to the Coriolis effect imparted by Earth's rotation. For instance, when the ITCZ is situated north of the Equator, the southeast trade wind changes to a southwest wind as it crosses the Equator. The ITCZ is formed by vertical motion largely appearing as convective activity of thunderstorms driven by solar heating, which effectively draw air in; these are the trade winds.[2] The ITCZ is effectively a tracer of the ascending branch of the Hadley cell and is wet. The dry descending branch is the horse latitudes.

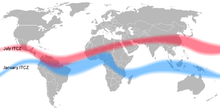

The location of the ITCZ gradually varies with the seasons, roughly corresponding with the location of the thermal equator. As the heat capacity of the oceans is greater than air over land, migration is more prominent over land. Over the oceans, where the convergence zone is better defined, the seasonal cycle is more subtle, as the convection is constrained by the distribution of ocean temperatures.[3] Sometimes, a double ITCZ forms, with one located north and another south of the Equator, one of which is usually stronger than the other. When this occurs, a narrow ridge of high pressure forms between the two convergence zones.

ITCZ over oceans vs. land

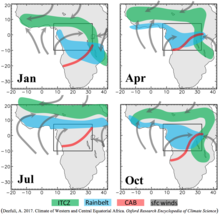

The ITCZ is commonly defined as an equatorial zone where the trade winds converge. Rainfall seasonality is traditionally attributed to the north–south migration of the ITCZ, which follows the sun. Although this is largely valid over the equatorial oceans, the ITCZ and the region of maximum rainfall can be decoupled over the continents.[4][5] The equatorial precipitation over land is not simply a response to just the surface convergence. Rather, it is modulated by a number of regional features such as local atmospheric jets and waves, proximity to the oceans, terrain-induced convective systems, moisture recycling, and spatiotemporal variability of land cover and albedo.[4]

South Pacific convergence zone

The South Pacific convergence zone (SPCZ) is a reverse-oriented, or west-northwest to east-southeast aligned, trough extending from the west Pacific warm pool southeastwards towards French Polynesia. It lies just south of the equator during the Southern Hemisphere warm season, but can be more extratropical in nature, especially east of the International Date Line. It is considered the largest and most important piece of the ITCZ, and has the least dependence upon heating from a nearby land mass during the summer than any other portion of the monsoon trough.[6] The southern ITCZ in the southeast Pacific and southern Atlantic, known as the SITCZ, occurs during the Southern Hemisphere fall between 3° and 10° south of the equator east of the 140th meridian west longitude during cool or neutral El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) patterns. When ENSO reaches its warm phase, otherwise known as El Niño, the tongue of lowered sea surface temperatures due to upwelling off the South American continent disappears, which causes this convergence zone to vanish as well.[7]

Effects on weather

Variation in the location of the intertropical convergence zone drastically affects rainfall in many equatorial nations, resulting in the wet and dry seasons of the tropics rather than the cold and warm seasons of higher latitudes. Longer term changes in the intertropical convergence zone can result in severe droughts or flooding in nearby areas.

In some cases, the ITCZ may become narrow, especially when it moves away from the equator; the ITCZ can then be interpreted as a front along the leading edge of the equatorial air.[8] There appears to be a 15 to 25-day cycle in thunderstorm activity along the ITCZ, which is roughly half the wavelength of the Madden–Julian oscillation (MJO).[9]

Within the ITCZ the average winds are slight, unlike the zones north and south of the equator where the trade winds feed. As trans-equator sea voyages became more common, sailors in the eighteenth century named this belt of calm the doldrums because of the calm, stagnant, or inactive winds.

Role in tropical cyclone formation

Tropical cyclogenesis depends upon low-level vorticity as one of its six requirements, and the ITCZ fills this role as it is a zone of wind change and speed, otherwise known as horizontal wind shear. As the ITCZ migrates to tropical - subtropical latitudes and even beyond (Shandong province of the People's Republic of China) during the respective hemisphere's summer season, increasing Coriolis force makes the formation of tropical cyclones within this zone more possible. Surges of higher pressure from high latitudes can enhance tropical disturbances along its axis.[10] In the north Atlantic and the northeastern Pacific oceans, tropical waves move along the axis of the ITCZ causing an increase in thunderstorm activity, and clusters of thunderstorms can develop under weak vertical wind shear.

Hazards

Thunderstorms along the Intertropical Convergence Zone played a role in the loss of Air France Flight 447, which left Rio de Janeiro–Galeão International Airport on Sunday, 31 May 2009, at about 7:00 p.m. local time (6:00 p.m. EDT or 10:00 p.m. UTC) and had been expected to land at Charles de Gaulle Airport near Paris on Monday, 1 June 2009, at 11:15 a.m. (5:15 a.m. EDT or 9:15 a.m. UTC).[11] The aircraft crashed with no survivors while flying through a series of large ITCZ thunderstorms, and ice forming rapidly on airspeed sensors was the precipitating cause for a cascade of human errors which ultimately doomed the flight. Most aircraft flying these routes are able to avoid the larger convective cells without incident.

In the Age of Sail, to find oneself becalmed in this region in a hot and muggy climate could mean death when wind was the only effective way to propel ships across the ocean. Calm periods within the doldrums could strand ships for days or weeks. Even today, leisure and competitive sailors attempt to cross the zone as quickly as possible as the erratic weather and wind patterns may cause unexpected delays.

In literature

The doldrums are notably described in Samuel Taylor Coleridge's poem The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1798) and also provide a metaphor for the initial state of boredom and indifference of Milo, the child hero of Norton Juster's classic children's novel The Phantom Tollbooth.

Notes

- Barry, Roger Graham; Chorley, Richard J. (1992). Atmosphere, weather, and climate. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-07760-6. OCLC 249331900.

Atmosphere, weather, and climate.

- "Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone". JetStream - Online School for Weather. NOAA. 2007-10-24. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- "Inter Tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) - SKYbrary Aviation Safety". www.skybrary.aero. Retrieved 2018-04-12.

- Dezfuli, Amin (2017-03-29). "Climate of Western and Central Equatorial Africa". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Climate Science. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190228620.013.511. ISBN 9780190228620.

- Nicholson, Sharon E. (February 2018). "The ITCZ and the Seasonal Cycle over Equatorial Africa". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 99 (2): 337–348. Bibcode:2018BAMS...99..337N. doi:10.1175/bams-d-16-0287.1. ISSN 0003-0007.

- E. Linacre and B. Geerts. Movement of the South Pacific convergence zone Retrieved on 2006-11-26.

- Semyon A. Grodsky; James A. Carton (2003-02-15). "The Intertropical Convergence Zone in the South Atlantic and the Equatorial Cold Tongue" (PDF). University of Maryland, College Park. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- Djurić, D: Weather Analysis. Prentice Hall, 1994. ISBN 0-13-501149-3.

- Patrick A. Harr. Tropical Cyclone Formation/Structure/Motion Studies. Office of Naval Research Retrieved on 2006-11-26. Archived November 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- C.-P. Chang, J.E. Erickson, and K.M. Lau. Northeasterly Cold Surges and Near-Equatorial Disturbances over the Winter MONEX Area during December 1974. Part I: Synoptic Aspects. Retrieved on 2007-04-26.

- "Q & A Turbulences" 1.June.2009 The Guardian

External links

| Look up doldrums in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Intertropical Convergence Zone. |