Sustainable development

Sustainable Development is the organizing principle for meeting human development goals while simultaneously sustaining the ability of natural systems to provide the natural resources and ecosystem services on which the economy and society depends. The desired result is a state of society where living conditions and resources are used to continue to meet human needs without undermining the integrity and stability of the natural system. Sustainable development can be defined as development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

While the modern concept of sustainable development is yet derived mostly from the 1987 Brundtland Report, it is also rooted in earlier ideas about sustainable forest management and twentieth-century environmental concerns. As the concept developed, it has shifted its focus more towards the economic development, social development and environmental protection for future generations. It has been suggested that "the term 'sustainability' should be viewed as humanity's target goal of human-ecosystem equilibrium, while 'sustainable development' refers to the holistic approach and temporal processes that lead us to the end point of sustainability".[1] Modern economies are endeavoring to reconcile ambitious economic development and obligations of preserving natural resources and ecosystems, as the two are usually seen as of conflicting nature. Instead of holding climate change commitments and other sustainability measures as a remedy to economic development, turning and leveraging them into market opportunities will do greater good. The economic development brought by such organized principles and practices in an economy is called Managed Sustainable Development (MSD).

The concept of sustainable development has been, and still is, subject to criticism, including the question of what is to be sustained in sustainable development. It has been argued that there is no such thing as a sustainable use of a non-renewable resource, since any positive rate of exploitation will eventually lead to the exhaustion of earth's finite stock;[2]:13 this perspective renders the Industrial Revolution as a whole unsustainable.[3]:20f[4]:61–67[5]:22f It has also been argued that the meaning of the concept has opportunistically been stretched from 'conservation management' to 'economic development', and that the Brundtland Report promoted nothing but a business as usual strategy for world development, with an ambiguous and insubstantial concept attached as a public relations slogan. (see below).[6]:48–54[7]:94–99

History of sustainability

Sustainability can be defined as the practice of maintaining world processes of productivity indefinitely—natural or human-made—by replacing resources used with resources of equal or greater value without degrading or endangering natural biotic systems.[9] Sustainable development ties together concern for the carrying capacity of natural systems with the social, political, and economic challenges faced by humanity. Sustainability Science is the study of the concepts of sustainable development and environmental science. There is an additional focus on the present generations' responsibility to regenerate, maintain and improve planetary resources for use by future generations.[10]:3–8

Sustainable development has its roots in ideas about sustainable forest management which were developed in Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries.[11][8]:6–16 In response to a growing awareness of the depletion of timber resources in England, John Evelyn argued that "sowing and planting of trees had to be regarded as a national duty of every landowner, in order to stop the destructive over- exploitation of natural resources" in his 1662 essay Sylva. In 1713 Hans Carl von Carlowitz, a senior mining administrator in the service of Elector Frederick Augustus I of Saxony published Sylvicultura economics, a 400-page work on forestry. Building upon the ideas of Evelyn and French minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert, von Carlowitz developed the concept of managing forests for sustained yield.[11] His work influenced others, including Alexander von Humboldt and Georg Ludwig Hartig, eventually leading to the development of a science of forestry. This, in turn, influenced people like Gifford Pinchot, first head of the US Forest Service, whose approach to forest management was driven by the idea of wise use of resources, and Aldo Leopold whose land ethic was influential in the development of the environmental movement in the 1960s.[11][8]

Following the publication of Rachel Carson's Silent Spring in 1962, the developing environmental movement drew attention to the relationship between economic growth and development and environmental degradation. Kenneth E. Boulding in his influential 1966 essay The Economics of the Coming Spaceship Earth identified the need for the economic system to fit itself to the ecological system with its limited pools of resources.[8] Another milestone was the 1968 article by Garrett Hardin that popularized the term "tragedy of the commons".[12] One of the first uses of the term sustainable in the contemporary sense was by the Club of Rome in 1972 in its classic report on the Limits to Growth, written by a group of scientists led by Dennis and Donella Meadows of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Describing the desirable "state of global equilibrium", the authors wrote: "We are searching for a model output that represents a world system that is sustainable without sudden and uncontrolled collapse and capable of satisfying the basic material requirements of all of its people."[10] That year also saw the publication of the influential A Blueprint for Survival book.[13][14]

Following the Club of Rome report, an MIT research group prepared ten days of hearings on "Growth and Its Implication for the Future" (Roundtable Press, 1973)[15] for the US Congress, the first hearings ever held on sustainable development. William Flynn Martin, David Dodson Gray, and Elizabeth Gray prepared the hearings under the Chairmanship of Congressman John Dingell.

In 1980 the International Union for the Conservation of Nature published a world conservation strategy that included one of the first references to sustainable development as a global priority[16] and introduced the term "sustainable development".[17]:4 Two years later, the United Nations World Charter for Nature raised five principles of conservation by which human conduct affecting nature is to be guided and judged.[18] In 1987 the United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development released the report Our Common Future, commonly called the Brundtland Report. The report included what is now one of the most widely recognised definitions of sustainable development.[19][20]

Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. It contains within it two key concepts:

· The concept of 'needs', in particular, the essential needs of the world's poor, to which overriding priority should be given; and

· The idea of limitations imposed by the state of technology and social organization on the environment's ability to meet present and future needs.— World Commission on Environment and Development, Our Common Future (1987)

Since the Brundtland Report, the concept of sustainable development has developed beyond the initial intergenerational framework to focus more on the goal of "socially inclusive and environmentally sustainable economic growth".[17]:5 In 1992, the UN Conference on Environment and Development published the Earth Charter, which outlines the building of a just, sustainable, and peaceful global society in the 21st century. The action plan Agenda 21 for sustainable development identified information, integration, and participation as key building blocks to help countries achieve development that recognises these interdependent pillars. It emphasises that in sustainable development everyone is a user and provider of information. It stresses the need to change from old sector-centered ways of doing business to new approaches that involve cross-sectoral co-ordination and the integration of environmental and social concerns into all development processes. Furthermore, Agenda 21 emphasises that broad public participation in decision making is a fundamental prerequisite for achieving sustainable development.[21]

Under the principles of the United Nations Charter the Millennium Declaration identified principles and treaties on sustainable development, including economic development, social development and environmental protection. Broadly defined, sustainable development is a systems approach to growth and development and to manage natural, produced, and social capital for the welfare of their own and future generations. The term sustainable development as used by the United Nations incorporates both issues associated with land development and broader issues of human development such as education, public health, and standard of living.

A 2013 study concluded that sustainability reporting should be reframed through the lens of four interconnected domains: ecology, economics, politics and culture.[22]

Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) is defined as education that encourages changes in knowledge, skills, values and attitudes to enable a more sustainable and equitable society. ESD aims to empower and equip current and future generations to meet the needs using a balanced and integrated approach to the economic, social and environmental dimensions of sustainable development.[23]

The Concept of Sustainable Developed

The concept of ESD was born from the need for education to address the growing and changing environmental challenges facing the planet. To do this, education must change to provide the knowledge, skills, values and attitudes that empower learners to contribute to sustainable development. At the same time, education must be strengthened in all agendas, programmes, and activities that promote sustainable development. Sustainable development must be integrated into education and education must be integrated into sustainable development. ESD promotes the integration of these critical sustainability issues in local and global contexts into the curriculum to prepare learners to understand and respond to the changing world. ESD aims to produce learning outcomes that include core competencies such as critical and systematic thinking, collaborative decision-making, and taking responsibility for the present and future generations. Since traditional single-directional delivery of knowledge is not sufficient to inspire learners to take action as responsible citizens, ESD entails rethinking the learning environment, physical and virtual. The learning environment itself must adapt and apply a whole-institution approach to embed the philosophy of sustainable development. Building the capacity of educators and policy support at international, regional, national and local levels helps drive changes in learning institutions. Empowered youth and local communities interacting with education institutions become key actors in advancing sustainable development.[23] It is a great gift of god.

UN Decade for Sustainable Development

The launch of the UN Decade of Education for sustainable development (2005–2014) started a global movement to reorient education to address the challenges of sustainable development. Building on the achievement of the Decade, stated in the Aichi-Nagoya Declaration on ESD, UNESCO endorsed the Global Action Programme on ESD (GAP) in the 37th session of its General Conference. Acknowledged by UN general assembly Resolution A/RES/69/211 and launched at the UNESCO World Conference on ESD in 2014, the GAP aims to scale-up actions and good practices. UNESCO has a major role, along with its partners, in bringing about key achievements to ensure the principles of ESD are promoted through formal, non-formal and informal education.[24]

International recognition of ESD as the key enabler for sustainable development is growing steadily. The role of ESD was recognized in three major UN summits on sustainable development: the 1992 UN Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; the 2002 World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) in Johannesburg, South Africa; and the 2012 UN Conference on Sustainable Development (UNCSD) in Rio de Janeiro. Other key global agreements such as the Paris Agreement (Article 12) also recognize the importance of ESD. Today, ESD is arguably at the heart of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and its 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (United Nations, 2015). The SDGs recognize that all countries must stimulate action in the following key areas – people, planet, prosperity, peace and partnership – to tackle the global challenges that are crucial for the survival of humanity. ESD is explicitly mentioned in Target 4.7 of SDG4, which aims to ensure that all learners acquire the knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development and is understood as an important means to achieve all the other 16 SDGs (UNESCO, 2017).[23]

Sub-groups

|

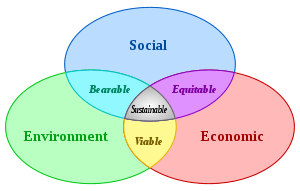

| Scheme of sustainable development: at the confluence of three constituent parts. (2006) |

Sustainable development can be thought of in terms of three spheres, dimensions, domains or pillars, i.e. the environment, the economy and society. The three-sphere framework was initially proposed by the economist Rene Passet in 1979.[25] It has also been worded as "economic, environmental and social" or "ecology, economy and equity".[26] This has been expanded by some authors to include a fourth pillar of culture, institutions or governance,[26] or alternatively reconfigured as four domains of the social – ecology, economics, politics and culture,[27] thus bringing economics back inside the social, and treating ecology as the intersection of the social and the natural.[28]

Environmental (or ecological)

The ecological stability of human settlements is part of the relationship between humans and their natural, social and built environments.[29] Also termed human ecology, this broadens the focus of sustainable development to include the domain of human health. Fundamental human needs such as the availability and quality of air, water, food and shelter are also the ecological foundations for sustainable development;[30] addressing public health risk through investments in ecosystem services can be a powerful and transformative force for sustainable development which, in this sense, extends to all species.[31]

Environmental sustainability concerns the natural environment and how it endures and remains diverse and productive. Since natural resources are derived from the environment, the state of air, water, and the climate are of particular concern. The IPCC Fifth Assessment Report outlines current knowledge about scientific, technical and socio-economic information concerning climate change, and lists options for adaptation and mitigation.[32] Environmental sustainability requires society to design activities to meet human needs while preserving the life support systems of the planet. This, for example, entails using water sustainably, using renewable energy, and sustainable material supplies (e.g. harvesting wood from forests at a rate that maintains the biomass and biodiversity).

An unsustainable situation occurs when natural capital (the sum total of nature's resources) is used up faster than it can be replenished. Sustainability requires that human activity only uses nature's resources at a rate at which they can be replenished naturally. Inherently the concept of sustainable development is intertwined with the concept of carrying capacity. Theoretically, the long-term result of environmental degradation is the inability to sustain human life. Such degradation on a global scale should imply an increase in human death rate until population falls to what the degraded environment can support. If the degradation continues beyond a certain tipping point or critical threshold it would lead to eventual extinction for humanity.[33]

| Consumption of natural resources | State of environment | Sustainability |

|---|---|---|

| More than nature's ability to replenish | Environmental degradation | Not sustainable |

| Equal to nature's ability to replenish | Environmental equilibrium | Steady state economy |

| Less than nature's ability to replenish | Environmental renewal | Environmentally sustainable |

Integral elements for a sustainable development are research and innovation activities. A telling example is the European environmental research and innovation policy, which aims at defining and implementing a transformative agenda to greening the economy and the society as a whole so to achieve a truly sustainable development. Research and innovation in Europe is financially supported by the programme Horizon 2020, which is also open to participation worldwide.[34] A promising direction towards sustainable development is to design systems that are flexible and reversible.[35][36]

Pollution of the public resources is really not a different action, it just is a reverse tragedy of the commons, in that instead of taking something out, something is put into the commons. When the costs of polluting the commons are not calculated into the cost of the items consumed, then it becomes only natural to pollute, as the cost of pollution is external to the cost of the goods produced and the cost of cleaning the waste before it is discharged exceeds the cost of releasing the waste directly into the commons. So, the only way to solve this problem is by protecting the ecology of the commons by making it, through taxes or fines, more costly to release the waste directly into the commons than would be the cost of cleaning the waste before discharge.[37]

So, one can try to appeal to the ethics of the situation by doing the right thing as an individual, but in the absence of any direct consequences, the individual will tend to do what is best for the person and not what is best for the common good of the public. Once again, this issue needs to be addressed. Because, left unaddressed, the development of the commonly owned property will become impossible to achieve in a sustainable way. So, this topic is central to the understanding of creating a sustainable situation from the management of the public resources that are used for personal use.

Agriculture

Sustainable agriculture consists of environment friendly methods of farming that allow the production of crops or livestock without damage to human or natural systems. It involves preventing adverse effects to soil, water, biodiversity, surrounding or downstream resources—as well as to those working or living on the farm or in neighbouring areas. The concept of sustainable agriculture extends intergenerationally, passing on a conserved or improved natural resource, biotic, and economic base rather than one which has been depleted or polluted.[38] Elements of sustainable agriculture include permaculture, agroforestry, mixed farming, multiple cropping, and crop rotation.[39] It involves agricultural methods that do not undermine the environment, smart farming technologies that enhance a quality environment for humans to thrive and reclaiming and transforming deserts into farmlands(Herman Daly, 2017).

Numerous sustainability standards and certification systems exist, including organic certification, Rainforest Alliance, Fair Trade, UTZ Certified, Bird Friendly, and the Common Code for the Coffee Community (4C).[40][41]

Economics

| Part of a series on |

| Ecological economics |

|---|

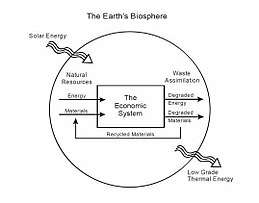

Humanity's economic system viewed as a subsystem of the global environment |

|

Works

|

It has been suggested that because of rural poverty and overexploitation, environmental resources should be treated as important economic assets, called natural capital.[42] Economic development has traditionally required a growth in the gross domestic product. This model of unlimited personal and GDP growth may be over. Sustainable development may involve improvements in the quality of life for many but may necessitate a decrease in resource consumption.[43] According to ecological economist Malte Faber, ecological economics is defined by its focus on nature, justice, and time. Issues of intergenerational equity, irreversibility of environmental change, uncertainty of long-term outcomes, and sustainable development guide ecological economic analysis and valuation.[44]

As early as the 1970s, the concept of sustainability was used to describe an economy "in equilibrium with basic ecological support systems".[45] Scientists in many fields have highlighted The Limits to Growth,[46][47] and economists have presented alternatives, for example a 'steady-state economy', to address concerns over the impacts of expanding human development on the planet.[5] In 1987 the economist Edward Barbier published the study The Concept of Sustainable Economic Development, where he recognised that goals of environmental conservation and economic development are not conflicting and can be reinforcing each other.[48]

A World Bank study from 1999 concluded that based on the theory of genuine savings, policymakers have many possible interventions to increase sustainability, in macroeconomics or purely environmental.[49] Several studies have noted that efficient policies for renewable energy and pollution are compatible with increasing human welfare, eventually reaching a golden-rule steady state.[50][51][52][53]

The study, Interpreting Sustainability in Economic Terms, found three pillars of sustainable development, interlinkage, intergenerational equity, and dynamic efficiency.[54]

But Gilbert Rist points out that the World Bank has twisted the notion of sustainable development to prove that economic development need not be deterred in the interest of preserving the ecosystem. He writes: "From this angle, 'sustainable development' looks like a cover-up operation. ... The thing that is meant to be sustained is really 'development', not the tolerance capacity of the ecosystem or of human societies."[55]

The World Bank, a leading producer of environmental knowledge, continues to advocate the win-win prospects for economic growth and ecological stability even as its economists express their doubts.[56] Herman Daly, an economist for the Bank from 1988 to 1994, writes:

When authors of WDR '92 [the highly influential 1992 World Development Report that featured the environment] were drafting the report, they called me asking for examples of "win-win" strategies in my work. What could I say? None exists in that pure form; there are trade-offs, not "win-wins." But they want to see a world of "win-wins" based on articles of faith, not fact. I wanted to contribute because WDRs are important in the Bank, [because] task managers read [them] to find philosophical justification for their latest round of projects. But they did not want to hear about how things really are, or what I find in my work...[57]

A meta review in 2002 looked at environmental and economic valuations and found a lack of "sustainability policies".[58] A study in 2004 asked if we consume too much.[59] A study concluded in 2007 that knowledge, manufactured and human capital (health and education) has not compensated for the degradation of natural capital in many parts of the world.[60] It has been suggested that intergenerational equity can be incorporated into a sustainable development and decision making, as has become common in economic valuations of climate economics.[61] A meta review in 2009 identified conditions for a strong case to act on climate change, and called for more work to fully account of the relevant economics and how it affects human welfare.[62] According to free-market environmentalist John Baden "the improvement of environment quality depends on the market economy and the existence of legitimate and protected property rights". They enable the effective practice of personal responsibility and the development of mechanisms to protect the environment. The State can in this context "create conditions which encourage the people to save the environment".[63]

Misum, Mistra Center for Sustainable Markets, based at Stockholm School of Economics, aims to provide policy research and advice to Swedish and international actors on Sustainable Markets. Misum is a cross-disciplinary and multi-stakeholder knowledge center dedicated to sustainability and sustainable markets and contains three research platforms: Sustainability in Financial Markets (Mistra Financial Systems), Sustainability in Production and Consumption and Sustainable Socio-Economic Development.[64]

Environmental economics

The total environment includes not just the biosphere of earth, air, and water, but also human interactions with these things, with nature, and what humans have created as their surroundings.[65]

As countries around the world continue to advance economically, they put a strain on the ability of the natural environment to absorb the high level of pollutants that are created as a part of this economic growth. Therefore, solutions need to be found so that the economies of the world can continue to grow, but not at the expense of the public good. In the world of economics the amount of environmental quality must be considered as limited in supply and therefore is treated as a scarce resource. This is a resource to be protected. One common way to analyze possible outcomes of policy decisions on the scarce resource is to do a cost-benefit analysis. This type of analysis contrasts different options of resource allocation and, based on an evaluation of the expected courses of action and the consequences of these actions, the optimal way to do so in the light of different policy goals can be elicited.[66]

Benefit-cost analysis basically can look at several ways of solving a problem and then assigning the best route for a solution, based on the set of consequences that would result from the further development of the individual courses of action, and then choosing the course of action that results in the least amount of damage to the expected outcome for the environmental quality that remains after that development or process takes place. Further complicating this analysis are the interrelationships of the various parts of the environment that might be impacted by the chosen course of action. Sometimes it is almost impossible to predict the various outcomes of a course of action, due to the unexpected consequences and the amount of unknowns that are not accounted for in the benefit-cost analysis.

Energy

Sustainable energy is clean and can be used over a long period of time. Unlike fossil fuels and biofuels that provide the bulk of the worlds energy, renewable energy sources like hydroelectric, solar and wind energy produce far less pollution.[67][68] Solar energy is commonly used on public parking meters, street lights and the roof of buildings.[69] Wind power has expanded quickly, its share of worldwide electricity usage at the end of 2014 was 3.1%.[70] Most of California's fossil fuel infrastructures are sited in or near low-income communities, and have traditionally suffered the most from California's fossil fuel energy system. These communities are historically left out during the decision-making process, and often end up with dirty power plants and other dirty energy projects that poison the air and harm the area. These toxicants are major contributors to health problems in the communities. As renewable energy becomes more common, fossil fuel infrastructures are replaced by renewables and we may begin to see a Renewable energy transition, providing better social equity to these communities.[71] Overall, and in the long run, sustainable development in the field of energy is also deemed to contribute to economic sustainability and national security of communities, thus being increasingly encouraged through investment policies.[72]

Manufacturing

Technology

One of the core concepts in sustainable development is that technology can be used to assist people to meet their developmental needs. Technology to meet these sustainable development needs is often referred to as appropriate technology, which is an ideological movement (and its manifestations) originally articulated as intermediate technology by the economist E. F. Schumacher in his influential work Small Is Beautiful and now covers a wide range of technologies.[73] Both Schumacher and many modern-day proponents of appropriate technology also emphasise the technology as people-centered.[74] Today appropriate technology is often developed using open source principles, which have led to open-source appropriate technology (OSAT) and thus many of the plans of the technology can be freely found on the Internet.[75] OSAT has been proposed as a new model of enabling innovation for sustainable development.[76][77]

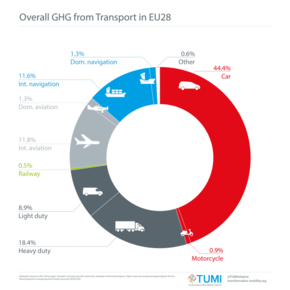

Transport

Transportation is a large contributor to greenhouse gas emissions. It is said that one-third of all gases produced are due to transportation.[78] Motorized transport also releases exhaust fumes that contain particulate matter which is hazardous to human health and a contributor to climate change.[79]

Sustainable transport has many social and economic benefits that can accelerate local sustainable development. According to a series of reports by the Low Emission Development Strategies Global Partnership (LEDS GP), sustainable transport can help create jobs,[80] improve commuter safety through investment in bicycle lanes and pedestrian pathways,[81] make access to employment and social opportunities more affordable and efficient. It also offers a practical opportunity to save people's time and household income as well as government budgets,[82] making investment in sustainable transport a 'win-win' opportunity.

Some Western countries are making transportation more sustainable in both long-term and short-term implementations.[83] An example is the modification in available transportation in Freiburg, Germany. The city has implemented extensive methods of public transportation, cycling, and walking, along with large areas where cars are not allowed.[78]

Since many Western countries are highly automobile-oriented, the main transit that people use is personal vehicles. About 80% of their travel involves cars.[78] Therefore, California, is one of the highest greenhouse gases emitters in the United States. The federal government has to come up with some plans to reduce the total number of vehicle trips to lower greenhouse gases emission. Such as:

- Improve public transit through the provision of larger coverage area in order to provide more mobility and accessibility, new technology to provide a more reliable and responsive public transportation network.[84]

- Encourage walking and biking through the provision of wider pedestrian pathway, bike share stations in downtowns, locate parking lots far from the shopping center, limit on street parking, slower traffic lane in downtown area.

- Increase the cost of car ownership and gas taxes through increased parking fees and tolls, encouraging people to drive more fuel efficient vehicles. This can produce a social equity problem, since lower income people usually drive older vehicles with lower fuel efficiency. Government can use the extra revenue collected from taxes and tolls to improve public transportation and benefit poor communities.[85]

Other states and nations have built efforts to translate knowledge in behavioral economics into evidence-based sustainable transportation policies.

Business

The most broadly accepted criterion for corporate sustainability constitutes a firm's efficient use of natural capital. This eco-efficiency is usually calculated as the economic value added by a firm in relation to its aggregated ecological impact.[86] This idea has been popularised by the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD) under the following definition: "Eco-efficiency is achieved by the delivery of competitively priced goods and services that satisfy human needs and bring quality of life, while progressively reducing ecological impacts and resource intensity throughout the life-cycle to a level at least in line with the earth's carrying capacity" (DeSimone and Popoff, 1997: 47).[87]

Similar to the eco-efficiency concept but so far less explored is the second criterion for corporate sustainability. Socio-efficiency[88] describes the relation between a firm's value added and its social impact. Whereas, it can be assumed that most corporate impacts on the environment are negative (apart from rare exceptions such as the planting of trees) this is not true for social impacts. These can be either positive (e.g. corporate giving, creation of employment) or negative (e.g. work accidents, mobbing of employees, human rights abuses). Depending on the type of impact socio-efficiency thus either tries to minimise negative social impacts (i.e. accidents per value added) or maximise positive social impacts (i.e. donations per value added) in relation to the value added.

Both eco-efficiency and socio-efficiency are concerned primarily with increasing economic sustainability. In this process they instrumentalise both natural and social capital aiming to benefit from win-win situations. However, as Dyllick and Hockerts[88] point out the business case alone will not be sufficient to realise sustainable development. They point towards eco-effectiveness, socio-effectiveness, sufficiency, and eco-equity as four criteria that need to be met if sustainable development is to be reached.[89]

CASI Global, New York "CSR & Sustainability together lead to sustainable development. CSR as in corporate social responsibility is not what you do with your profits, but is the way you make profits. This means CSR is a part of every department of the company value chain and not a part of HR / independent department. Sustainability as in effects towards Human resources, Environment and Ecology has to be measured within each department of the company." CASI Global

Income

At the present time, sustainable development can reduce poverty. Sustainable development reduces poverty through financial (among other things, a balanced budget), environmental (living conditions), and social (including equality of income) means.[90]

Architecture

In sustainable architecture the recent movements of New Urbanism and New Classical architecture promote a sustainable approach towards construction, that appreciates and develops smart growth, architectural tradition and classical design.[91][92] This in contrast to modernist and International Style architecture, as well as opposing to solitary housing estates and suburban sprawl, with long commuting distances and large ecological footprints.[93] Both trends started in the 1980s. (Sustainable architecture is predominantly relevant to the economics domain while architectural landscaping pertains more to the ecological domain.)

Politics

A study concluded that social indicators and, therefore, sustainable development indicators, are scientific constructs whose principal objective is to inform public policy-making.[94] The International Institute for Sustainable Development has similarly developed a political policy framework, linked to a sustainability index for establishing measurable entities and metrics. The framework consists of six core areas:

- International trade and investment

- Economic policy

- Climate change and energy

- Measurement and assessment

- Natural resource management

- Communication technologies.

The United Nations Global Compact Cities Programme has defined sustainable political development in a way that broadens the usual definition beyond states and governance. The political is defined as the domain of practices and meanings associated with basic issues of social power as they pertain to the organisation, authorisation, legitimation and regulation of a social life held in common. This definition is in accord with the view that political change is important for responding to economic, ecological and cultural challenges. It also means that the politics of economic change can be addressed. They have listed seven subdomains of the domain of politics:[95]

- Organization and governance

- Law and justice

- Communication and critique

- Representation and negotiation

- Security and accord

- Dialogue and reconciliation

- Ethics and accountability

This accords with the Brundtland Commission emphasis on development that is guided by human rights principles (see above).

Culture

.jpg)

Working with a different emphasis, some researchers and institutions have pointed out that a fourth dimension should be added to the dimensions of sustainable development, since the triple-bottom-line dimensions of economic, environmental and social do not seem to be enough to reflect the complexity of contemporary society. In this context, the Agenda 21 for culture and the United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG) Executive Bureau lead the preparation of the policy statement "Culture: Fourth Pillar of Sustainable Development", passed on 17 November 2010, in the framework of the World Summit of Local and Regional Leaders – 3rd World Congress of UCLG, held in Mexico City. This document inaugurates a new perspective and points to the relation between culture and sustainable development through a dual approach: developing a solid cultural policy and advocating a cultural dimension in all public policies. The Circles of Sustainability approach distinguishes the four domains of economic, ecological, political and cultural sustainability.[96][97][98]

Other organizations have also supported the idea of a fourth domain of sustainable development. The Network of Excellence "Sustainable Development in a Diverse World",[99] sponsored by the European Union, integrates multidisciplinary capacities and interprets cultural diversity as a key element of a new strategy for sustainable development. The Fourth Pillar of Sustainable Development Theory has been referenced by executive director of IMI Institute at UNESCO Vito Di Bari[100] in his manifesto of art and architectural movement Neo-Futurism, whose name was inspired by the 1987 United Nations' report Our Common Future. The Circles of Sustainability approach used by Metropolis defines the (fourth) cultural domain as practices, discourses, and material expressions, which, over time, express continuities and discontinuities of social meaning.[95]

Cultural elements in sustainable development frameworks

Recently, human-centered design and cultural collaboration have been popular frameworks for sustainable development in marginalized communities.[101][102][103][104] These frameworks involve open dialogue which entails sharing, debating, and discussing, as well as holistic evaluation of the site of development.[101][102][103][104] Especially when working on sustainable development in marginalized communities, cultural emphasis is a crucial factor in project decisions, since it largely affects aspects of their lives and traditions.[101] Collaborators use Articulation Theory in co-designing. This allows for them to understand each other's thought process and their comprehension of the sustainable projects.[101] By using the method of co-design, the beneficiaries' holistic needs are being considered.[101][103] Final decisions and implementations are made with respect to sociocultural and ecological factors.[104][103][102][101]

Human centered design

The user-oriented framework relies heavily on user participation and user feedback in the planning process.[105] Users are able to provide new perspective and ideas, which can be considered in a new round of improvements and changes.[105] It is said that increased user participation in the design process can garner a more comprehensive understanding of the design issues, due to more contextual and emotional transparency between researcher and participant.[105] A key element of human centered design is applied ethnography, which was a research method adopted from cultural anthropology.[105] This research method requires researchers to be fully immersed in the observation so that implicit details are also recorded.[105]

Life cycle analysis

Many communities express environmental concerns, so life cycle analysis is often conducted when assessing the sustainability of a product or prototype.[106][103][101] The assessment is done in stages with meticulous cycles of planning, design, implementation, and evaluation.[107] The decision to choose materials is heavily weighted on its longevity, renewability, and efficiency. These factors ensure that researchers are conscious of community values that align with positive environmental, social, and economic impacts.[106]

Themes

Progress

The United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development (UNCSD; also known as Rio 2012) was the third international conference on sustainable development, which aimed at reconciling the economic and environmental goals of the global community. An outcome of this conference was the development of the Sustainable Development Goals that aim to promote sustainable progress and eliminate inequalities around the world. However, few nations met the World Wide Fund for Nature's definition of sustainable development criteria established in 2006.[108] Although some nations are more developed than others, all nations are constantly developing because each nation struggles with perpetuating disparities, inequalities and unequal access to fundamental rights and freedoms.[109]

Measurement

In 2007 a report for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency stated: "While much discussion and effort has gone into sustainability indicators, none of the resulting systems clearly tells us whether our society is sustainable. At best, they can tell us that we are heading in the wrong direction, or that our current activities are not sustainable. More often, they simply draw our attention to the existence of problems, doing little to tell us the origin of those problems and nothing to tell us how to solve them."[110] Nevertheless, a majority of authors assume that a set of well defined and harmonised indicators is the only way to make sustainability tangible. Those indicators are expected to be identified and adjusted through empirical observations (trial and error).[111]

The most common critiques are related to issues like data quality, comparability, objective function and the necessary resources.[112] However a more general criticism is coming from the project management community: How can a sustainable development be achieved at global level if we cannot monitor it in any single project?[113][114]

The Cuban-born researcher and entrepreneur Sonia Bueno suggests an alternative approach that is based upon the integral, long-term cost-benefit relationship as a measure and monitoring tool for the sustainability of every project, activity or enterprise.[115][116] Furthermore, this concept aims to be a practical guideline towards sustainable development following the principle of conservation and increment of value rather than restricting the consumption of resources.

Reasonable qualifications of sustainability are seen U.S. Green Building Council's (USGBC) Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED). This design incorporates some ecological, economic, and social elements. The goals presented by LEED design goals are sustainable sites, water efficiency, energy consumption and atmospheric emission reduction, material and resources efficiency, and indoor environmental quality. Although amount of structures for sustainability development is many, these qualification has become a standard for sustainable building.

Recent research efforts created also the SDEWES Index to benchmark the performance of cities across aspects that are related to energy, water and environment systems. The SDEWES Index consists of 7 dimensions, 35 indicators, and close to 20 sub-indicators. It is currently applied to 58 cities.[117]

Natural capital

The sustainable development debate is based on the assumption that societies need to manage three types of capital (economic, social, and natural), which may be non-substitutable and whose consumption might be irreversible.[88] Leading ecological economist and steady-state theorist Herman Daly,[5] for example, points to the fact that natural capital can not necessarily be substituted by economic capital. While it is possible that we can find ways to replace some natural resources, it is much more unlikely that they will ever be able to replace eco-system services, such as the protection provided by the ozone layer, or the climate stabilizing function of the Amazonian forest. In fact natural capital, social capital and economic capital are often complementarities. A further obstacle to substitutability lies also in the multi-functionality of many natural resources. Forests, for example, not only provide the raw material for paper (which can be substituted quite easily), but they also maintain biodiversity, regulate water flow, and absorb CO2.

Another problem of natural and social capital deterioration lies in their partial irreversibility. The loss of biodiversity, for example, is often definitive. The same can be true for cultural diversity. For example, with globalisation advancing quickly the number of indigenous languages is dropping at alarming rates. Moreover, the depletion of natural and social capital may have non-linear consequences. Consumption of natural and social capital may have no observable impact until a certain threshold is reached. A lake can, for example, absorb nutrients for a long time while actually increasing its productivity. However, once a certain level of algae is reached lack of oxygen causes the lake's ecosystem to break down suddenly.[118]

Business-as-usual

If the degradation of natural and social capital has such important consequence the question arises why action is not taken more systematically to alleviate it. Cohen and Winn[119] point to four types of market failure as possible explanations: First, while the benefits of natural or social capital depletion can usually be privatised, the costs are often externalised (i.e. they are borne not by the party responsible but by society in general). Second, natural capital is often undervalued by society since we are not fully aware of the real cost of the depletion of natural capital. Information asymmetry is a third reason—often the link between cause and effect is obscured, making it difficult for actors to make informed choices. Cohen and Winn close with the realization that contrary to economic theory many firms are not perfect optimisers. They postulate that firms often do not optimise resource allocation because they are caught in a "business as usual" mentality.

Education

Main page: Education for sustainable development

Education must be revisited in light of a renewed vision of sustainable human and social development that is both equitable and viable. This vision of sustainability must take into consideration the social, environmental and economic dimensions of human development and the various ways in which these relate to education: 'An empowering education is one that builds the human resources we need to be productive, to continue to learn, to solve problems, to be creative, and to live together and with nature in peace and harmony. When nations ensure that such an education is accessible to all throughout their lives, a quiet revolution is set in motion: education becomes the engine of sustainable development and the key to a better world.'[120][121]

Insubstantial stretching of the term

It has been argued that since the 1960s, the concept of sustainable development has changed from "conservation management" to "economic development", whereby the original meaning of the concept has been stretched somewhat.[6]:48–54

In the 1960s, the international community realised that many African countries needed national plans to safeguard wildlife habitats, and that rural areas had to confront the limits imposed by soil, climate and water availability. This was a strategy of conservation management. In the 1970s, however, the focus shifted to the broader issues of the provisioning of basic human needs, community participation as well as appropriate technology use throughout the developing countries (and not just in Africa). This was a strategy of economic development, and the strategy was carried even further by the Brundtland Commission's report on Our Common Future when the issues went from regional to international in scope and application.[6]:48–54 In effect, the conservationists were crowded out and superseded by the developers.

But shifting the focus of sustainable development from conservation to development has had the imperceptible effect of stretching the original forest management term of sustainable yield from the use of renewable resources only (like forestry), to now also accounting for the use of non-renewable resources (like minerals).[2]:13 This stretching of the term has been questioned. Thus, environmental economist Kerry Turner has argued that literally, there can be no such thing as overall "sustainable development" in an industrialised world economy that remains heavily dependent on the extraction of earth's finite stock of exhaustible mineral resources: "It makes no sense to talk about the sustainable use of a non-renewable resource (even with substantial recycling effort and reduction in use rates). Any positive rate of exploitation will eventually lead to exhaustion of the finite stock."[2]:13

In effect, it has been argued that the industrial revolution as a whole is unsustainable.[3]:20f[4]:61–67[5]:22f[122]:52

One critic has argued that the Brundtland Commission promoted nothing but a business as usual strategy for world development, with the ambiguous and insubstantial concept of "sustainable development" attached as a public relations slogan:[7]:94–99 The report on Our Common Future was largely the result of a political bargaining process involving many special interest groups, all put together to create a common appeal of political acceptability across borders. After World War II, the notion of "development" had been established in the West to imply the projection of the American model of society onto the rest of the world. In the 1970s and 1980s, this notion was broadened somewhat to also imply human rights, basic human needs and finally, ecological issues. The emphasis of the report was on helping poor nations out of poverty and meeting the basic needs of their growing populations—as usual. This issue demanded more economic growth, also in the rich countries, who would then import more goods from the poor countries to help them out—as usual. When the discussion switched to global ecological limits to growth, the obvious dilemma was left aside by calling for economic growth with improved resource efficiency, or what was termed "a change in the quality of growth". However, most countries in the West had experienced such improved resource efficiency since the early-20th century already and as usual; only, this improvement had been more than offset by continuing industrial expansion, to the effect that world resource consumption was now higher than ever before—and these two historical trends were completely ignored in the report. Taken together, the policy of perpetual economic growth for the entire planet remained virtually intact. Since the publication of the report, the ambiguous and insubstantial slogan of "sustainable development" has marched on worldwide.[7]:94–99

See also

- Agroecology

- Applied sustainability

- Biocapacity

- Circles of Sustainability

- Circular economy

- Computational sustainability

- Conservation biology

- Conservation development

- Cradle-to-cradle

- Cultural footprint

- Development Studies

- Ecological economics

- Ecological deficit

- Ecological footprint

- Ecological modernization

- Ecologically sustainable development

- Environmental issue

- Environmental justice

- Environmental racism

- Earth system governance

- Farmer Research Committee

- Futures of Education

- Gender and development

- Green development

- Micro-sustainability

- Outline of sustainability

- Overshoot

- Purple economy

- Regenerative design

- Social sustainability

- Sustainable coffee

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Sustainable fishery

- Sustainable forest management

- Sustainable land management

- Sustainable living

- Sustainable redevelopment

- Sustainable yield

- Sustainopreneurship

- Weak and strong sustainability

- Zero-carbon city

Sources

![]()

![]()

References

- Shaker, Richard Ross (September 2015). "The spatial distribution of development in Europe and its underlying sustainability correlations". Applied Geography. 63. p. 35. doi:10.1016/j.apgeog.2015.07.009.

- Turner, R. Kerry (1988). "Sustainability, Resource Conservation and Pollution Control: An Overview". In Turner, R. Kerry (ed.). Sustainable Environmental Management. London: Belhaven Press.

- Georgescu-Roegen, Nicholas (1971). The Entropy Law and the Economic Process (Full book accessible at Scribd). Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674257801.

- Rifkin, Jeremy (1980). Entropy: A New World View (PDF contains only the title and contents pages of the book). New York: The Viking Press. ISBN 978-0670297177.

- Daly, Herman E. (1992). Steady-state economics (2nd ed.). London: Earthscan Publications.

- O'Riordan, Timothy (1993). "The Politics of Sustainability". In Turner, R. Kerry (ed.). Sustainable Environmental Economics and Management: Principles and Practice. London: Belhaven Press.

- Perez-Carmona, Alexander (2013). "Growth: A Discussion of the Margins of Economic and Ecological Thought" (Article accessible at SlideShare). In Meuleman, Louis (ed.). Transgovernance. Advancing Sustainability Governance. Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 83–161. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-28009-2_3. ISBN 9783642280085.

- Blewitt, John (2015). Understanding Sustainable Development (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415707824. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- Lynn R. Kahle, Eda Gurel-Atay, Eds (2014). Communicating Sustainability for the Green Economy. New York: M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-3680-5.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Finn, Donovan (2009). Our Uncertain Future: Can Good Planning Create Sustainable Communities?. Champaign-Urbana: University of Illinois.

- Ulrich Grober: Deep roots — A conceptual history of "sustainable development" (Nachhaltigkeit), Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung, 2007

- Hardin, Garrett (13 December 1968). "The Tragedy of the Commons". Science. 162 (3859): 1243–1248. doi:10.1126/science.162.3859.1243. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 5699198.

- "A Blueprint for Survival". The New York Times. 5 February 1972. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- "The Ecologist January 1972: a blueprint for survival". The Ecologist. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- "Growth and its implications for the future" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016.

- World Conservation Strategy: Living Resource Conservation for Sustainable Development (PDF). International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. 1980.

- Sachs, Jeffrey D. (2015). The Age of Sustainable Development. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231173155.

- World Charter for Nature, United Nations, General Assembly, 48th Plenary Meeting, 28 October 1982

- Brundtland Commission (1987). "Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development". United Nations. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Smith, Charles; Rees, Gareth (1998). Economic Development, 2nd edition. Basingstoke: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-72228-2.

- Will Allen. 2007."Learning for Sustainability: Sustainable Development."

- Liam Magee; Andy Scerri; Paul James; James A. Thom; Lin Padgham; Sarah Hickmott; Hepu Deng; Felicity Cahill (2013). "Reframing social sustainability reporting: Towards an engaged approach". Environment, Development and Sustainability. 15: 225–243. doi:10.1007/s10668-012-9384-2.

- Issues and trends in education for sustainable development. Paris: UNESCO. 2018. p. 7. ISBN 978-92-3-100244-1.

- Issues and trends in education for sustainable development. Paris: UNESCO. 2018. p. 8. ISBN 978-92-3-100244-1.

- Passet, René (1 January 1979). L'Économique et le vivant (in French). Payot.

- United Nations (2014). Prototype Global Sustainable Development Report (Online unedited ed.). New York: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Division for Sustainable Development.

- James, Paul; with Magee, Liam; Scerri, Andy; Steger, Manfred B. (2015). Urban Sustainability in Theory and Practice: Circles of Sustainability. London: Routledge.

- Circles of Sustainability Urban Profile Process Archived 12 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine and Scerri, Andy; James, Paul (2010). "Accounting for sustainability: Combining qualitative and quantitative research in developing 'indicators' of sustainability". International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 13 (1): 41–53. doi:10.1080/13645570902864145.

- http://citiesprogramme.com/aboutus/our-approach/circles-of-sustainability Archived 2 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine; Scerri, Andy; James, Paul (2010). "Accounting for sustainability: Combining qualitative and quantitative research in developing 'indicators' of sustainability". International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 13 (1): 41–53. doi:10.1080/13645570902864145..

- White, F; Stallones, L; Last, JM. (2013). Global Public Health: Ecological Foundations. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-975190-7.

- Bringing human health and wellbeing back into sustainable development. In: IISD Annual Report 2011-12. http://www.iisd.org/pdf/2012/annrep_2011_2012_en.pdf

- IPCC Fifth Assessment Report (2014). "Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability" (PDF). Geneva (Switzerland): IPCC. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Russell, Caden Jacobs & Fran (7 September 2019). Biochemistry and Forestry Management. Scientific e-Resources. ISBN 978-1-83947-173-5.

- See Horizon 2020 – the EU's new research and innovation programme http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-13-1085_en.htm

- Fawcett, William; Hughes, Martin; Krieg, Hannes; Albrecht, Stefan; Vennström, Anders (2012). "Flexible strategies for long-term sustainability under uncertainty". Building Research. 40 (5): 545–557. doi:10.1080/09613218.2012.702565.

- Zhang, S.X.; V. Babovic (2012). "A real options approach to the design and architecture of water supply systems using innovative water technologies under uncertainty". Journal of Hydroinformatics. 14: 13–29. doi:10.2166/hydro.2011.078.

- Daly, H. E. Economics, Ecology, Ethics: Essays toward a Steady-State Economy. Hardin, G. "The tragedy of the commons". New York and San Francisco: W. H. Freeman and Company. pp. 100–114.

- Networld-Project (9 February 1998). "Environmental Glossary". Green-networld.com. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- Ben Falk, The resilient farm and homestead: An innovative permaculture and whole systems design approach. Chelsea Green, 2013. pp. 61–78.

- Manning, Stephen; Boons, Frank; Von Hagen, Oliver; Reinecke, Juliane (2012). "National Contexts Matter: The Co-Evolution of Sustainability Standards in Global Value Chains". Ecological Economics. 83: 197–209. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2011.08.029. SSRN 1752655.

- Reinecke, Juliane; Manning, Stephen; Von Hagen, Oliver (2012). "The Emergence of a Standards Market: Multiplicity of Sustainability Standards in the Global Coffee Industry". Organization Studies. 33 (5/6): 789–812. doi:10.1177/0170840612443629. SSRN 1970343.

- Barbier, Edward B. (2006). Natural Resources and Economic Development. https://books.google.com/books?id=fYrEDA-VnyUC&pg=PA45: Cambridge University Press. pp. 44–45. ISBN 9780521706513. Retrieved 8 April 2014.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Brown, L. R. (2011). World on the Edge. Earth Policy Institute. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-08029-2.

- Malte Faber. (2008). How to be an ecological economist. Ecological Economics 66(1):1–7. Preprint.

- Stivers, R. 1976. The Sustainable Society: Ethics and Economic Growth. Philadelphia: Westminster Press.

- Meadows, D.H., D.L. Meadows, J. Randers, and W.W. Behrens III. 1972. The Limits to Growth. Universe Books, New York, NY. ISBN 0-87663-165-0

- Meadows, D.H.; Randers, Jørgen; Meadows, D.L. (2004). Limits to Growth: The 30-Year Update. Chelsea Green Publishing. ISBN 978-1-931498-58-6.

- Barbier, E. (1987). "The Concept of Sustainable Economic Development". Environmental Conservation. 14 (2): 101–110. doi:10.1017/S0376892900011449.

- Hamilton, K.; Clemens, M. (1999). "Genuine savings rates in developing countries". World Bank Economy Review. 13 (2): 333–356. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.452.7532. doi:10.1093/wber/13.2.333.

- Ayong Le Kama, A. D. (2001). "Sustainable growth renewable resources, and pollution". Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control. 25 (12): 1911–1918. doi:10.1016/S0165-1889(00)00007-5.

- Chichilnisky, G.; Heal, G.; Beltratti, A. (1995). "A Green Golden Rule". Economics Letters. 49 (2): 175–179. doi:10.1016/0165-1765(95)00662-Y.

- Endress, L.; Roumasset, J. (199). "Golden rules for sustainable resource management". Economic Record. 70 (210): 266–277.

- Endress, L.; Roumasset, J.; Zhou, T. (2005). "Sustainable Growth with Environmental Spillovers". Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization. 58 (4): 527–547. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.529.5305. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2004.09.003.

- Stavins, R.; Wagner, A.; Wagner, G. (2003). "Interpreting Sustainability in Economic Terms: Dynamic Efficiency Plus Intergenerational Equity". Economics Letters. 79 (3): 339–343. doi:10.1016/S0165-1765(03)00036-3. hdl:10419/119677.

- The History of Development, 3rd Ed. (New York: Zed, 2008) 194.

- Daniel P. Castillo, "Integral Ecology as a Liberationist Concept" in Theological Studies, Vol 77, 2, June 2016, 374.

- Michael Goldman, Imperial Nature: the World Bank and the Struggle for Justice in the Age of Globalization. (New Haven: Yale University, 2005), 128, quoted in Theological Studies, supra.

- Pezzey, John C. V.; Michael A., Toman (2002). "The Economics of Sustainability: A Review of Journal Articles" (PDF). —. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- Arrow, K. J.; Dasgupta, P.; Goulder, L.; Daily, G.; Ehrlich, P. R.; Heal, G. M.; Levin, S.; Maler, K-G.; Schneider, S.; Starrett, D. A.; Walker, B. (2004). "Are we consuming too much?" (PDF). Journal of Economic Perspectives. 18 (3): 147–172. doi:10.1257/0895330042162377. JSTOR 3216811.

- Dasgupta, P. (2007). "The idea of sustainable development". Sustainability Science. 2 (1): 5–11. doi:10.1007/s11625-007-0024-y.

- Heal, G. (2009). "Climate Economics: A Meta-Review and Some Suggestions for Future Research". Review of Environmental Economics and Policy. 3 (1): 4–21. doi:10.1093/reep/ren014.

- Heal, Geoffrey (2009). "Climate Economics: A Meta-Review and Some Suggestions for Future Research". Review of Environmental Economics and Policy. 3: 4–21. doi:10.1093/reep/ren014. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- Baden, John, L'économie politique du développement durable (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2008 Document de l'ICREI.

- "Misum".

- Environmental Economics, 3rd Edition. J.J. Seneca/M.K. Taussig. 1984. Page 3.

- Barbier, E.B.; Markandya, A.; Pearce, D.W. (1990). "Environmental sustainability and cost-benefit analysis". Environment and Planning A. 22 (9): 1259–1266. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.335.1749. doi:10.1068/a221259.

- "Biofuels cause pollution, not as green as thought – study". Reuters. 7 January 2013.

- Fainstein, Susan S. 2000. "New Directions in Planning Theory," Urban Affairs Review 35:4 (March)

- Bedsworf, Louise W.; Hanak, Ellen (2010). "Adaptation to Climate Change". Journal of the American Planning Association. 76: 4.

- http://www.ren21.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/REN12-GSR2015_Onlinebook_low1.pdf pg31

- Campbell, Scott. 1996. "Green Cities, Growing Cities, Just Cities?: Urban planning and the Contradictions of Sustainable Development," Journal of the American Planning Association

- Farah, Paolo Davide (2015). "Sustainable Energy Investments and National Security: Arbitration and Negotiation Issues". Journal of World Energy Law and Business. 8 (6). SSRN 2695579.

- Hazeltine, B.; Bull, C. (1999). Appropriate Technology: Tools, Choices, and Implications. New York: Academic Press. pp. 3, 270. ISBN 978-0-12-335190-6.

- Akubue, Anthony (Winter–Spring 2000). "Appropriate Technology for Socioeconomic Development in Third World Countries". The Journal of Technology Studies. 26 (1): 33–43.Retrieved March 2011. doi:10.21061/jots.v26i1.a.6.

- Pearce, Joshua M. (2012). "The Case for Open Source Appropriate Technology". Environment, Development and Sustainability. 14 (3): 425–431. doi:10.1007/s10668-012-9337-9.

- Pearce, Joshua; Albritton, Scott; Grant, Gabriel; Steed, Garrett; Zelenika, Ivana (2012). "A new model for enabling innovation in appropriate technology for sustainable development". Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy. 8 (2): 42–53. doi:10.1080/15487733.2012.11908095.

- Zelenika, I.; Pearce, J.M. (2014). "Innovation Through Collaboration: Scaling up Technological Solutions for Sustainable Development". Environment, Development and Sustainability. 16 (6): 1299–1316. doi:10.1007/s10668-014-9528-7.

- Buehler, Ralph; Pucher, John (2011). "Sustainable Transport in Freiburg: Lessons from Germany's Environmental Capital". International Journal of Sustainable Transportation. 5: 43–70. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.233.1827. doi:10.1080/15568311003650531.

- "LEDS in Practice: Breathe clean". The Low Emission Development Strategies Global Partnership.

- "LEDS in Practice: Create jobs". The Low Emission Development Strategies Global Partnership.

- "LEDS in Practice: Make roads safe". The Low Emission Development Strategies Global Partnership.

- "LEDS in Practice: Save money and time". The Low Emission Development Strategies Global Partnership.

- Barbour, Elissa and Elizabeth A. Deakin. 2012. "Smart Growth Planning for Climate Protection"

- Murthy, A.S. Narasimha Mohle, Henry. Transportation Engineering Basics (2nd Edition). (American Society of Civil Engineers 2001).

- Levine, Jonathan. 2013. "Urban Transportation and Social Equity: Transportation Planning Paradigms that Impede Policy Reform," in Naomi Carmon and Susan S. Fainstein, eds. Policy, Planning and people: promoting Justice in Urban Development (Penn)

- Schaltegger, S. & Sturm, A. 1998. Eco-Efficiency by Eco-Controlling. Zürich: vdf.

- DeSimone, L. & Popoff, F. 1997. Eco-efficiency: The business link to sustainable development. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Dyllick, T.; Hockerts, K. (2002). "Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability". Business Strategy and the Environment. 11 (2): 130–141. doi:10.1002/bse.323.

- Young, William; Tilley, Fiona (2006). "Can businesses move beyond efficiency? The shift toward effectiveness and equity in the corporate sustainability debate" (PDF). Business Strategy and the Environment. 15 (6): 402–415. doi:10.1002/bse.510. ISSN 1099-0836.

- Walczak, Damian; Adamiak, Stanisław (7 April 2014). "Catholic social teaching, sustainable development and social solidarism in the context of social security". Copernican Journal of Finance & Accounting. 3 (1): 9–18. doi:10.12775/CJFA.2014.001.

- "The Charter of the New Urbanism". CNU. 20 April 2015.

- "Beauty, Humanism, Continuity between Past and Future". Traditional Architecture Group. Archived from the original on 5 March 2018. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- Issue Brief: Smart-Growth: Building Livable Communities. American Institute of Architects. Retrieved on 23 March 2014.

- Paul-Marie Boulanger (2008). "Sustainable development indicators: a scientific challenge, a democratic issue". S.A.P.I.EN.S. 1 (1). Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- http://citiesprogramme.com/archives/resource/circles-of-sustainability-urban-profile-process Archived 12 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine Liam Magee; Andy Scerri; Paul James; James A. Thom; Lin Padgham; Sarah Hickmott; Hepu Deng; Felicity Cahill (2013). "Reframing social sustainability reporting: Towards an engaged approach". Environment, Development and Sustainability. 15: 225–243. doi:10.1007/s10668-012-9384-2.

- United Cities and Local Governments, "Culture: Fourth Pillar of Sustainable Development" Archived 10 August 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- "Principles for a Positive Urban Future".

- James, Paul. "Assessing Cultural Sustainability: Agenda 21 for Culture". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Sus.Div". Sus.Div. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- "Agreement between UNESCO and the City of Milan concerning the International Multimedia Institute (IMI) – Appointment of Executive Director — UNESCO Archives ICA AtoM catalogue". Atom.archives.unesco.org. 8 October 1999. Retrieved 2014-01-17.

- Edmunds, David S.; Shelby, Ryan; James, Angela (November 2013). "Tribal Housing, Codesign, and Cultural Sovereignty". Science, Technology & Society, & Human Values. 38 (6): 801–828. doi:10.1177/0162243913490812. JSTOR 43671157.

- Saiyed, Zahraa (September 2017). "Native American Storytelling Toward Symbiosis and Sustainable Design". Energy Research & Social Science. 31: 249–252. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2017.05.029.

- Martin, Tania (September 2005). "Thinking the Other: Towards Cultural Diversity in Architecture". Journal of Architectural Education. 59: 3–16. doi:10.1111/j.1531-314X.2005.00001.x.

- Necefer, Len; Wong-Parodi, Gabrielle; Paulina, Jaramillo; Small, Mitchell J. (May 2015). "Energy development and Native Americans: Values and beliefs about energy from the Navajo Nation". Energy Research & Social Science. 7: 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2015.02.007.

- Del'Era, Claudio; Landoni, Paolo (June 2014). "Living Lab: A Methodology between User Centered Design and Participatory Design". Creativity & Innovation Management. 23 (2): 137–154. doi:10.1111/caim.12061. hdl:11311/959178.

- Mestre, Ana; Cooper, Tim (2017). "Circular Product Design. A Multiple Loops Life Cycle Design Approach for the Circular Economy". Design Journal. 20: S1620–S1635. doi:10.1080/14606925.2017.1352686.

- Vila, Carlos (May 2016). "An Approach to Conceptual and Embodiment Design within A New Product Development Life Cycle Framework". International Journal of Production Research. 54 (10): 2856–2874. doi:10.1080/00207543.2015.1110632.

- "Living Planet Report 2006" (PDF). World Wide Fund for Nature, Zoological Society of London, Global Footprint Network. 24 October 2006. p. 19. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 August 2018. Retrieved 18 August 2012.; World failing on sustainable development Archived 9 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Nussbaum, Martha (2011). Creating Capabilities: The Human Development Approach. Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. pp. 16. ISBN 978-0-674-05054-9.

- "Joy E. Hecht, Can Indicators and Accounts Really Measure Sustainability? Considerations for the U.S. Environmental Protection". Archived from the original on 10 April 2014. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- Reed, Mark S. (2006). "An adaptive learning process for developing and applying sustainability indicators with local communities" (PDF). Ecological Economics. 59 (4): 406–418. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2005.11.008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 18 February 2011.

- "Annette Lang, Ist Nachhaltigkeit messbar?, Uni Hannover, 2003" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 August 2011. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- "Project Management T-kit, Council of Europe and European Commission, Strasbourg, 2000" (PDF). Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- "Do global targets matter?, The Environment Times, Poverty Times #4, UNEP/GRID-Arendal, 2010". Grida.no. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- "Sostenibilidad en la construcción. Calidad integral y rentabilidad en instalaciones hidro-sanitarias, Revista de Arquitectura e Ingeniería, Matanzas, 2009". Empai-matanzas.co.cu. 17 January 2009. Archived from the original on 30 October 2011. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- "Transforming the water and waste water infrastructure into an efficient, profitable and sustainable system, Revista de Arquitectura e Ingeniería, Matanzas, 2010" (PDF). Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- "SDEWES Centre – SDEWES Index". www.sdewes.org. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- Newcomb, Doug. "Nutrients: Too Much of a Good Thing". United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Archived from the original on 12 October 2006. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- Cohen, B.; Winn, M. I. (2007). "Market imperfections, opportunity and sustainable entrepreneurship". Journal of Business Venturing. 22 (1): 29–49. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2004.12.001.

- Power, C (2015). The Power of Education: Education for All, Development, Globalisation and UNESCO. London, Springer.

- Rethinking Education: Towards a global common good? (PDF). UNESCO. 2015. pp. 31–32. ISBN 978-92-3-100088-1.

- Duncan, Richard C. (2015). "The Olduvai Theory. Back to hunting and gathering" (PDF). The Social Contract. 25 (2): 52–54.

Further reading

- Ahmed, Faiz (2008). An Examination of the Development Path Taken by Small Island Developing States (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 October 2012. Retrieved 19 April 2012. (pp. 17–26)

- Atkinson, G., S. Dietz, and E. Neumayer (2009). Handbook of Sustainable Development. Edward Elgar Publishing, ISBN 1848444729.

- Bakari, Mohamed El-Kamel. "Globalization and Sustainable Development: False Twins?." New Global Studies 7.3: 23–56. ISSN (Online) 1940-0004, ISSN (Print) 2194–6566, doi:10.1515/ngs-2013-021, November 2013.

- Bertelsmann Stiftung, ed. (2013). Winning Strategies for a Sustainable Future. Reinhard Mohn Prize 2013. Verlag Bertelsmann Stiftung, Gütersloh. ISBN 978-3-86793-491-6.

- Beyerlin, Ulrich. Sustainable Development, Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law

- Borowy, Iris. Defining Sustainable Development for Our Common Future. A history of the World Commission on Environment and Development (Brundtland Commission), Milton Park: Routledge, 2014.

- Cook, Sarah & Esuna Dugarova (2014). "Rethinking Social Development for a Post-2015 World". Development. 57 (1): 30–35. doi:10.1057/dev.2014.25.

- Danilov-Danil'yan, Victor I., Losev, K.S., Reyf, Igor E. Sustainable Development and the Limitation of Growth: Future Prospects for World Civilization. Transl. Vladimir Tumanov. Ed. Donald Rapp. New York: Springer Praxis Books, 2009. at Google Books

- Edwards, A.R., and B. McKibben (2010). Thriving Beyond Sustainability: Pathways to a Resilient Society. New Society Publishers, ISBN 0865716412.

- Farah, Paolo Davide; Rossi, Piercarlo (2015). "Energy: Policy, Legal and Social-Economic Issues Under the Dimensions of Sustainability and Security". World Scientific Reference on Globalisation in Eurasia and the Pacific Rim. SSRN 2695701.

- Hickel, Jason (2019). "The contradiction of the sustainable development goals: Growth versus ecology on a finite planet". Sustainable Development. 27 (5): 873–884. doi:10.1002/sd.1947.

- Huesemann, M.H., and J.A. Huesemann (2011). Technofix: Why Technology Won't Save Us or the Environment, Chapter 6, "Sustainability or Collapse?", and Chapter 13, "The Design of Environmentally Sustainable and Socially Appropriate Technologies", New Society Publishers, ISBN 0865717044.

- James, Paul; Nadarajah, Yaso; Haive, Karen; Stead, Victoria (2012). Sustainable Communities, Sustainable Development: Other Paths for Papua New Guinea. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- James, Paul; with Magee, Liam; Scerri, Andy; Steger, Manfred B. (2015). Urban Sustainability in Theory and Practice: Circles of Sustainability. London: Routledge.

- Jarzombek, Mark, "Sustainability — Architecture: between Fuzzy Systems and Wicked Problems," Blueprints 21/1 (Winter 2003), pp. 6–9.

- Li, Rita Yi Man. Building Our Sustainable Cities " onsustainability.com, Building Our Sustainable Cities Illinois, Published by Common Ground Publishing.

- Partsvania, V. R. (2020). Profitability of multi-national corporations in the context of sustainable development: Scania business practices. Российский журнал менеджмента, 18(1), 103–116.

- Raudsepp-Hearne, C; Peterson, GD; Tengö, M; Bennett, EM; Holland, T; Benessaiah, K; MacDonald, GM; Pfeifer, L (2010). "Untangling the Environmentalist's Paradox: Why is Human Well-Being Increasing as Ecosystem Services Degrade?". BioScience. 60 (8): 576–589. doi:10.1525/bio.2010.60.8.4.

- Rogers, P., K.F. Jalal, and J.A. Boyd (2007). An Introduction to Sustainable Development. Routledge, ISBN 1844075214.

- Sianipar, C. P. M., Dowaki, K., Yudoko, G., & Adhiutama, A. (2013). Seven Pillars of Survivability: Appropriate Technology with a Human Face. European Journal of Sustainable Development (ECSDEV), 2(4), 1–18. ISSN 2239-5938.

- Tausch, Arno (2012). Globalization, the Human Condition, and Sustainable Development in the Twenty-first Century: Cross-national Perspectives and European Implications. With Almas Heshmati and a Foreword by Ulrich Brand (1st ed.). Anthem Press, London. ISBN 9780857284105.

- Van der Straaten, J., and J.C van den Bergh (1994). Towards Sustainable Development: Concepts, Methods, and Policy. Island Press, ISBN 1559633492.

- Wallace, Bill (2005). Becoming part of the solution : the engineer's guide to sustainable development. Washington, DC: American Council of Engineering Companies. ISBN 978-0-910090-37-7.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Sustainable development |

- Global Sustainable Development, an undergraduate degree program offered by the University of Warwick.