City of God (2002 film)

City of God (Portuguese: Cidade de Deus) is a 2002 Brazilian crime film co-directed by Fernando Meirelles and Kátia Lund, released in its home country in 2002 and worldwide in 2003. Bráulio Mantovani adapted the story from the 1997 novel of the same name written by Paulo Lins, but the plot is loosely based on real events. It depicts the growth of organized crime in the Cidade de Deus suburb of Rio de Janeiro, between the end of the 1960s and the beginning of the 1980s, with the film's closure depicting the war between the drug dealer Li'l Zé and vigilante-turned-criminal Knockout Ned. The tagline is "If you run, the beast catches you; if you stay, the beast eats you."

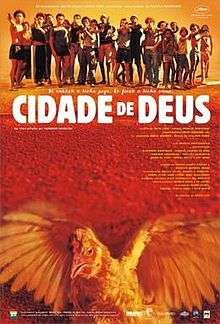

| City of God | |

|---|---|

Original poster | |

| Portuguese | Cidade de Deus |

| Directed by | Fernando Meirelles[lower-alpha 1] |

| Produced by |

|

| Written by | Bráulio Mantovani |

| Based on | City of God by Paulo Lins |

| Starring |

|

| Music by |

|

| Cinematography | César Charlone |

| Edited by | Daniel Rezende |

Production company |

|

| Distributed by | Miramax Films |

Release date |

|

Running time | 130 minutes |

| Country | Brazil |

| Language | Portuguese |

| Budget | $3.3 million[1] |

| Box office | $30.6 million[2] |

The cast includes Alexandre Rodrigues, Leandro Firmino da Hora, Phellipe Haagensen, Douglas Silva, Alice Braga, and Seu Jorge. Most of the actors were, in fact, residents of favelas such as Vidigal and the Cidade de Deus itself.

The film received widespread critical acclaim and was nominated for four Academy Awards in 2004: Best Cinematography (César Charlone), Best Director (Meirelles), Best Film Editing (Daniel Rezende), and Best Writing (Adapted Screenplay) (Mantovani). In 2003, it was Brazil's entry for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, but it did not end up being nominated as one of the five finalists.

Meirelles and Lund went on to create the City of Men TV series and film City of Men (2007), which share some of the actors (notably leads Douglas Silva and Darlan Cunha) and their setting with City of God.

Plot

The film begins in medias res with an armed gang chasing after an escaped chicken in a favela called the Cidade de Deus ("City of God"). The chicken stops between the gang and the narrator, a young man nicknamed Rocket ("Buscapé").

The film flashes back to the 1960s where the favela is shown as a newly built housing project with few resources. Three impoverished, amateur thieves known as the "Tender Trio" – Shaggy ("Cabeleira"), Clipper ("Alicate"), and Rocket's older brother, Goose ("Marreco") – rob business owners and share the money with the community who, in turn, hide them from the police. Li'l Dice (Dadinho), a young boy, convinces them to hold up a motel and rob its occupants.

The gang resolves not to kill anyone and tells Li'l Dice to serve as a lookout. Instead, Li'l Dice guns down the motel occupants after falsely warning the trio that the police are coming. The massacre is brought to the police's attention, forcing the trio to split up: Clipper joins the Church, Shaggy is shot by the police while trying to escape the favela, and Goose is shot by Li'l Dice after taking his money while Li'l Dice's friend Benny (Bené), Shaggy's brother, watches.

In the 1970s, the favela has been transformed into an urban jungle. Rocket has joined a group of young hippies. He enjoys photography and likes one girl, Angélica, but his attempt to get close to her is ruined by a gang of petty criminal kids known as "The Runts". Li'l Dice, who now calls himself "Li'l Zé" ("Zé Pequeno"), has established a drug empire with Benny by eliminating all of the competition, except for Carrot, who is a good friend of Benny's.

Li'l Zé takes over 'the apartment', a known drug distribution center, and forces Carrot's manager Blacky ("Neguinho"), to work for him instead. Coincidentally, Rocket visits the apartment to get some drugs off Blacky for Angélica during the apartment raid. Through narration, Rocket momentarily considers attempting to kill Li'l Zé to avenge his brother but decides against it. He is let go after Benny tells Li'l Zé that Rocket is Goose's brother.

Sometime later, a relative peace comes over the City of God under the reign of Li'l Zé, who manages to avoid police attention. Benny decides to branch out of the drug dealer crowd and befriends Tiago, Angélica's ex-boyfriend, who introduces him to his (and Rocket's) friend group. Benny and Angélica begin dating. Together, they decide to leave the City and the drug trade.

During Benny's farewell party, Zé and Benny get into an argument. Blacky accidentally kills Benny while trying to shoot Li'l Zé. Benny's death leaves Li'l Zé unchecked. Carrot kills Blacky for endangering his life. Li'l Zé and a group of his soldiers start to make their way to Carrot's hideout to kill him.

On the way, Zé follows a girl who dismissed his advances at Benny's party. He beats up her boyfriend, a peaceful man named Knockout Ned (Mané Galinha), and rapes her. After Ned's brother stabs Li'l Zé, his gang retaliates by shooting into his house, killing his brother and uncle in the process. A gang war breaks out between Carrot and Li'l Zé. A vengeful Ned sides with Carrot.

The war is still ongoing a year later, in 1981, the origin forgotten. Both sides enlist more "soldiers" and Li'l Zé gives the Runts weapons. One day, Li'l Zé has Rocket take photos of him and his gang. AA reporter publishes the photos, a significant scoop since nobody can safely enter the City of God anymore. Rocket believes his life is endangered, as he thinks Li'l Zé will kill him for publishing the photo of him and his gang. The reporter takes Rocket in for the night, and he loses his virginity to her. Unbeknownst to him, Li'l Zé, jealous of Ned's media fame, is pleased with the photos and with his own increased notoriety.

Rocket returns to the City for more photographs, bringing the film back to its opening scene. Confronted by the gang, Rocket is surprised that Zé asks him to take pictures, but as he prepares to take the photo, the police arrive and then drive off when Carrot's gang arrives. In the ensuing gunfight, Ned is killed by a boy who has infiltrated his gang to avenge his father, a policeman whom Ned has shot. The police capture Li'l Zé and Carrot and plan to show Carrot off to the media. Since Li'l Zé has been bribing the police, they take all of Li'l Zé's money and let him go, but Rocket secretly photographs the scene. The Runts murder Zé to avenge the Runt murdered at the behest of Zé; they intend to run his criminal enterprise themselves.

Rocket contemplates whether to publish the cops' photo, expose corruption, and become famous, or the picture of Li'l Zé's dead body, which will get him an internship at the newspaper. He decides on the latter, fearing a violent response from the cops, as well as seeing the opportunity to pursue his dream. The film ends with the Runts walking around the City of God, making a hit list of the dealers they plan to kill to take over the drug business, including the Red Brigade.

Cast

Many characters are known only by nicknames. The literal translation of these nicknames is given next to their original Portuguese name; the names given in English subtitles are sometimes different.

| Name | Actor(s) | Name in English subtitles | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Buscapé ("Firecracker") | Alexandre Rodrigues (adult) Luis Otávio (child) | Rocket | The main narrator. A quiet, honest boy who dreams of becoming a photographer, and the only character who manages to prevent himself from being dragged down into corruption and murder during the gang wars. His real name is Wilson Rodrigues. |

| Zé Pequeno ("Little Joe" "Lil Zé") childhood: Dadinho ("Little Eddy" "Lil Dice") | Leandro Firmino da Hora (adult) Douglas Silva (child) | Li'l Zé Li'l Dice | A power-hungry, sociopathic drug lord who takes sadistic pleasure in killing his rivals. When his only friend, Benny, is killed, he is driven over the edge. "Dado" is a common nickname for Eduardo, and "inho" a diminutive suffix; "dado" also means "dice". As an adult, he changes his name to Zé Pequeno in Candomblé ceremony, a religion of African origin. Since it was chosen for him at that moment, it may be unrelated to his actual name. Zé is a nickname for José, while pequeno means "little". |

| Bené ("Benny") | Phellipe Haagensen (adult) Michel de Souza Gomes (child) | Benny | Zé's longtime partner in crime, he is a friendly City of God drug dealer who fancies himself a sort of Robin Hood, and eventually wants to lead an honest life. |

| Sandro, nicknamed Cenoura ("Carrot") | Matheus Nachtergaele | Carrot | A smaller-scale drug dealer who is friendly with Benny but is constantly threatened by Zé. |

| Mané Galinha ("Chicken Manny") | Seu Jorge | Knockout Ned | A handsome, charismatic ladies' man. Zé rapes Ned's girlfriend and then proceeds to kill several members of Ned's family. Ned joins forces with Carrot to retaliate against Zé. His name was changed for the English subtitles because in English, "chicken" is a term for a coward (in Brazil it denotes popularity among women). "Mané" is a nickname for Manuel. |

| Cabeleira ("Long Hair") | Jonathan Haagensen | Shaggy | Older brother of Bené ("Benny") and the leader of the Tender Trio ("Trio Ternura"), a group of thieves who share their profits with the population of the City of God. |

| Marreco ("Garganey") | Renato de Souza | Goose | One of the Tender Trio, and Rocket's brother. |

| Alicate ("Pliers") | Jefechander Suplino | Clipper | One of the Tender Trio. Later gives up crime and joins the Church. |

| Barbantinho ("Little twine") | Edson Oliveira (adult) Emerson Gomes (child) | Stringy | Childhood friend of Rocket. |

| Angélica | Alice Braga | Angélica | A friend and love interest of Rocket, and later Benny's girlfriend, who motivates Benny to abandon the criminal life. |

| Tiago | Daniel Zettel | Tiago | Angélica's boyfriend, who later becomes Li'l Zé's associate and a drug addict. |

| Filé com Fritas ("Steak with Fries") | Darlan Cunha | Steak with Fries | A young boy who joins Zé's gang. |

| Charles, nicknamed Tio Sam ("Uncle Sam") | Charles Paraventi | Charles / Uncle Sam | A weapons dealer. |

| Marina Cintra | Graziella Moretto | Marina Cintra | A journalist for Jornal do Brasil, who hires Rocket as a photographer. Rocket has his first sexual experience with her. |

| Touro ("Bull") | Luiz Carlos Ribeiro Seixas | Touro | An honest police officer. |

| Cabeção ("Big Head") | Maurício Marques | Melonhead | A corrupt police officer. |

| Lampião ("Lantern") | Thiago Martins | Lampião | Child leader of the Runts gang. |

| Otávio | Marcos Junqueira | Otávio | Child leader of the Runts gang. |

Production

On the bonus DVD, it is revealed that the only professional actor with years of filming experience was Matheus Nachtergaele, who played the supporting role of Carrot.[3] Most of the remaining cast were from real-life favelas, and in some cases, even the real-life City of God favela itself. According to Meirelles, amateur actors were used for two reasons: the lack of available professional black actors, and the desire for authenticity. Meirelles explained: "Today I can open a casting call and have 500 black actors, but just ten years ago this possibility did not exist. In Brazil, there were three or four young black actors and at the same time I felt that actors from the middle class could not make the film. I needed authenticity."[4]

Beginning around 2000, about a hundred children and young people were hand-picked and placed into an "actors' workshop" for several months.[3] In contrast to more traditional methods (e.g. studying theatre and rehearsing), it focused on simulating authentic street war scenes, such as a hold-up, a scuffle, a shoot-out etc. A lot came from improvisation, as it was thought better to create an authentic, gritty atmosphere. This way, the inexperienced cast soon learned to move and act naturally.[3] After filming, the crew could not leave the cast to return to their old lives in the favelas. Help groups were set up to help those involved in the production to build more promising futures.[5]

Meirelles went into the film with the intention of staying true to the "casual nature"[6] of the violence in the novel by Lins. Critic Jean Oppenheimer wrote on the production of the film saying that: "A second guiding principle was to avoid glamorising the violence" and that "many of the killings are either shown indistinctly or kept out of frame."[6]

Because the real Cidade de Deus favela was in conflict, a large majority of the film was shot in Cidade Alta, a different favela within Rio. During the production, slumlords did not allow for the production company to have their own security, so local security guards were hired for the safety of the set.[7]

Prior to City of God, Lund and Meirelles filmed the short film Golden Gate as a test run.[3] Golden Gate was shot while casting for City of God was in the initial stages.[8]

Reception

Box office

The film was screened out of competition at the 2002 Cannes Film Festival.[9] In Brazil, City of God garnered the largest audience for a domestic film in 2003, with over 3.1 million tickets sold, and a gross of 18.6 million reais ($10.3 million).[10] The film grossed over $7.5 million in the U.S. and over $30.5 million worldwide (in U.S. Dollars).[11]

Critical reception

City of God gathered 91% favorable reviews on Rotten Tomatoes, and 79% on Metacritic.[12][13] Empire chose it as the 177th best film of all time in 2008,[14] and TIME chose it as one of the 100 greatest films of all time.[15] Critic Roger Ebert gave the film a four-star review, writing "City of God churns with furious energy as it plunges into the story of the slum gangs of Rio de Janeiro. Breathtaking and terrifying, urgently involved with its characters, it announces a new director of great gifts and passions: Fernando Meirelles. Remember the name.".[16]

The film was not without criticism. Peter Rainer of New York Magazine stated that while the film was "powerful", it was also "rather numbing". John Powers of L.A. Weekly wrote that "[the film] whirs with energy for nearly its full 130-minute running time, it is oddly lacking in emotional heft for a work that aspires to be so epic – it is essentially a tarted up exploitation picture whose business is to make ghastly things fun".[17]

Ivana Bentes, a Brazilian film critic, criticised the film for its depiction of the favela and her view that it glorified issues of poverty and violence as means of "domestication of the most radical themes of culture and Brazilian cinema (…) as products for export."[18] Bentes targets the film specifically in saying that: "City of God promotes tourism in hell".[19]

City of God was ranked third in Film4's "50 Films to See Before You Die", and ranked No.7 in Empire magazine's "The 100 Best Films of World Cinema" in 2010.[20] It was also ranked No. 6 on The Guardian's list of "the 25 Best Action Movies Ever".[21] It was ranked No. 1 in Paste magazine's 50 best movies of the decade of the 2000s.[22]

In 2012, the Motion Picture Editors Guild listed City of God as the 17th best-edited film of all time based on a survey of its members.[23]

Top ten lists

The film appeared on several American critics' top ten lists of the best films of 2003.[24]

- 2nd – Chicago Sun Times (Roger Ebert) (for 2002)

- 2nd – Charlotte Observer (Lawrence Toppman)

- 2nd – Chicago Tribune (Marc Caro)

- 4th – New York Post (Jonathan Foreman)

- 4th – Time Magazine (Richard Corliss)

- 5th – Portland Oregonian (Shawn Levy)

- 7th – Chicago Tribune (Michael Wilmington)

- 10th – The Hollywood Reporter (Michael Rechtshaffen)

- 10th – New York Post (Megan Lehmann)

- 10th – The New York Times (Stephen Holden)

It is #38 on the BBC list of best 100 films of the 21st century.[25]

MV Bill's response

Brazilian rapper MV Bill, a resident of Cidade de Deus, provided his own criticisms on the film. He criticized the film as he believed it had a negative impact on the image of the favela. He wrote on the impact saying: "this film has brought no good to the favela, no social, moral, or human benefit."[26][27] He emphasised his opinion that the film was exploitative of the youth of the favela saying: "The world will know that they exploited the image of the children who live here in Cidade de Deus. What is obvious is that they are going to carry a bigger stigma throughout their lives; it has only become greater because of the film."[27]

Awards and nominations

City of God won fifty-five awards and received another twenty-nine nominations. Among those:

| Organization | Award | Recipient | Result | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards | Best Director | Fernando Meirelles | Nominated | [28] |

| Best Adapted Screenplay | Bráulio Mantovani | Nominated | ||

| Best Cinematography | César Charlone | Nominated | ||

| Best Film Editing | Daniel Rezende | Nominated | ||

| AFI Fest | Audience Award | Won | [29] | |

| Broadcast Film Critics Association Awards | Best Foreign Language Film | Nominated | [30] | |

| British Academy Film Awards | Best Editing | Daniel Rezende | Won | [31] |

| Best Foreign Film | Andrea Barata Ribeiro, Mauricio Andrade Ramos, Fernando Meirelles | Nominated | [32] | |

| British Independent Film Awards | Best Foreign Independent Film | Won | [33] | |

| Chicago Film Critics Association Awards | Best Foreign Language Film | Won | [34] | |

| Golden Globe Awards | Best Foreign Language Film | Nominated | [35] | |

| Golden Trailer Awards | Best Independent Foreign Film | Won | [36] | |

| Grande Prêmio do Cinema Brasileiro | Best Film | Won | [37] | |

| Best Director | Fernando Meirelles | Won | ||

| Best Adapted Screenplay | Bráulio Mantovani | Won | ||

| Best Cinematography | César Charlone | Won | ||

| Best Editing | Daniel Rezende | Won | ||

| Best Sound | Guilherme Ayrosa, Paulo Ricardo Nunes, Alessandro Laroca, Alejandro Quevedo, Carlos Honc, Roland Thai, Rudy Pi, Adam Sawelson | Won | ||

| Best Actor | Leandro Firmino | Nominated | [38] | |

| Best Actress | Roberta Rodrigues | Nominated | ||

| Best Supporting Actor | Jonathan Haagensen | Nominated | [39] | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Douglas Silva | Nominated | ||

| Best Supporting Actress | Alice Braga | Nominated | [40] | |

| Best Supporting Actress | Graziela Moretto | Nominated | ||

| Best Art Direction | Tulé Peak | Nominated | [41] | |

| Best Costume Design | Bia Salgado, Inês Salgado | Nominated | [42] | |

| Best Makeup | Anna Van Steen | Nominated | [43] | |

| Best Soundtrack | Antonio Pinto, Ed Côrtes | Nominated | [44] | |

| Independent Spirit Awards | Best Foreign Language Film | Fernando Meirelles | Nominated | [45] |

| Las Vegas Film Critics Society Awards | Best Foreign Language Film | Won | [46] | |

| Motion Picture Sound Editors | Best Sound Editing in a Foreign Film | Martín Hernández, Roland N. Thai, Alessandro Laroca | Won | [47] |

| New York Film Critics Circle Awards | Best Foreign Language Film | Won | [48] | |

| Prism Awards | Best Theatrical Film | Won | [49] | |

| Satellite Awards | Best Foreign Language Film | Won | [50] | |

| Southeastern Film Critics Association Awards | Best Foreign Language Film | Won | [51] | |

| Toronto Film Critics Association Awards | Best Foreign Language Film | Won | [52] | |

| Toronto International Film Festival | Visions Award – Special Citation | Won | [53] |

Music

The score to the film composed by Antonio Pinto and Ed Córtes. It was followed by two remix albums. Songs from the film:

- "Alvorada" (Cartola / Carlos Cachaça / Herminio B. Carvalho) - Cartola

- "Azul Da Cor Do Mar" (Tim Maia) - Tim Maia

- "Dance Across the Floor" (Harry Wayne Casey / Ronald Finch) - Jimmy Bo Horne

- "Get Up (I Feel Like Being a) Sex Machine" (James Brown / Bobby Byrd / Ronald R. Lenhoff) - James Brown

- "Hold Back the Water" (Randy Bachman / Robin Bachman / Charles Turner) - Bachman–Turner Overdrive

- "Hot Pants Road" (Charles Bobbit / James Brown / St Clair Jr Pinckney) - The J.B.'s

- "Kung Fu Fighting" (Carl Douglas) - Carl Douglas

- "Magrelinha" (Luiz Melodia) - Luiz Melodia

- "Metamorfose Ambulante" (Raul Seixas) - Raul Seixas

- "Na Rua, Na Chuva, Na Fazenda" (Hyldon) - Hyldon

- "Nem Vem Que Não Tem" (Carlos Imperial) - Wilson Simonal

- "O Caminho Do Bem" (Sérgio / Beto / Paulo) - Tim Maia

- "Preciso Me Encontrar" (Candeia) - Cartola

- "So Very Hard to Go" (Emilio Castillo / Stephen M. Kupka) - Tower of Power

Legacy

In an interview with Slant Magazine, Meirelles states he had met with Brazil's former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva who told him about the impact the film has had on both policies and public security within the country. The film has also sparked major increase in production shootings, with over 45 being done during 2002. Films such as The Motorcycle Diaries and The Intruder are some of the films which have used Brazil for film production.[54]

Brazilian academic Bianca Freire-Medeiros (who specialises in favela tourism) has found that since the film's release in 2002, favela tour participation has greatly increased. "After the movie...Rio de Janeiro favelas became...hyped", Leandro Firmino (who played Li'l Ze in the film) told interviewers in the documentary City of God - 10 Years Later. Around 40,000 people visit Rocinha (the most tourist-friendly of Rio's favelas) per year making it the fourth most visited "attraction" in Rio.[55]

In 2013, a documentary was released called City of God - 10 Years Later. The film reunites the cast and crew and takes a look at their lives after the original film was released. In a BBC article written at the time of the documentary's release, Firmino mentions that the cast had mixed careers after the film's release. Firmino says that Jefechander Suplino, the actor who played Clipper, could not be found by the documentary producers. His mother, however, believes him to still be alive, but is unaware of his whereabouts. Seu Jorge, who played Knockout Ned, had a better career after the film and is now a major musician and performed at the London 2012 Olympic Games closing ceremony.[56]

Notelist

- Co-directed by Kátia Lund

References

- Izmirlian, Pablo (4 September 2005). "From Way South of the Border, an Ecuadorean Thriller". The Washington Post. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- "City of God (2003) - Box Office Mojo". Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- City of God DVD extras

- Bessa, Priscila. "Dez anos depois, diretor de Cidade de Deus diz ter prejuízo de R$4 milhões". 4 June 2012. Internet Group / ig.com.br. Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- Vieira, Else R P (2005). "18". In Vieira, Else R P (ed.). City of God in Several Voices Brazilian Social Cinema as Action. Great Britain: Critical, Cultural and Communications Press. pp. 135–139. ISBN 1 905510 00 4.

- Oppenheimer, Jean (2005). "4". In Vieira, Else P R (ed.). City of God in Several Voices Brazilian Social Cinema as Action. Great Britain: Critical, Cultural and Communications Press. pp. 26–32. ISBN 1 905510 00 4.

- https://www.theguardian.com/film/2014/jun/09/how-we-made-city-of-god

- Kuykendall, Niija (2 May 2003). "We in Cinema: City of God Benefit". Black Film. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- "Festival de Cannes: City of God". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- "Informe 269" (PDF) (in Portuguese). Filme B. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2009.

- City of God at Box Office Mojo.

- City of God at Rotten Tomatoes.

- "City of God critic reviews". Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- The 500 Greatest Movies of All-Time: 184–175, Empire

- "City of God – ALL-TIME 100 movies". TIME. 12 February 2005. Archived from the original on 25 May 2005. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- "City of God (2002)". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- "City of God critic reviews". Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- Bentes, Ivana (2003). "8". In Nagib, Lúcia (ed.). The New Brazilian Cinema. University of Oxford: I.B. Tauris. pp. 121–136. ISBN 978-1-86064-878-6.

- Freire-Medeiros, Bianca (9 May 2011). "'I went to the City of God': Gringos, guns and the touristic favela". Journal of Latin American Cultural Studies. 20 (1): 25. doi:10.1080/13569325.2011.562631.

- "The 100 Best Films of World Cinema | 7. City of God". Empire.

- Fox, Killian (19 October 2010). "City of God: No 6 best action movie and war film of all time | Film | The Guardian". The Guardian. London.

- "The 50 Best Movies of the Decade (2000-2009)". Paste. 3 November 2009. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- "The 75 Best Edited Films". Editors Guild Magazine. 1 (3). May 2012.

- "Metacritic: 2003 Film Critic Top Ten Lists". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 25 December 2007. Retrieved 5 January 2008.

- "The 21st Century's 100 greatest films". BBC. 23 August 2016. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

- "REALIDADE E FICÇÃO Cidade de Deus sofre com o estigma da violência". Folha de Londrina (in Portuguese). February 2003. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- Bill, MV (2003). "15". In Vieira, Else R P (ed.). City of God in Several Voices Brazilian Social Cinema as Action. Great Britain: Critical, Cultural and Communications Press. pp. 123, 124. ISBN 1 905510 00 4.

- Gray, Tim (27 January 2004). "A wing-ding for 'The King'". Variety. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- Berkshire, Geoff (18 November 2002). "'Shoujyo' nabs AFI jury prize". Variety. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- Hirsch, Lisa (9 March 2003). "Handicapping Oscar". Variety. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- Dawtrey, Adam (23 February 2003). "High notes for 'Pianist'". Variety. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- "Kudos count". Variety. 15 February 2004. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- Dawtrey, Adam (4 November 2003). "'Dirty' sweeps BIFAs". Variety. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- Rooney, David (21 January 2004). "'King' reigns among Chi crix". Variety. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- Gray, Tim (19 December 2002). "Miramax & 'Chi' fly high". Variety. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- Berkshire, Geoff (26 May 2004). "'Stepford' steps off with best-trailer trophy". Variety. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- "Academia Brasileira de Cinema divulga lista dos melhores de 2002". Folha de S.Paulo (in Portuguese). Grupo Folha. 17 December 2003. Retrieved 16 February 2015 – via Universo Online.

- ""Oscar brasileiro" anuncia finalistas". O Estado de S. Paulo (in Portuguese). Grupo Estado. 3 November 2003. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- "Finalistas 2003: Melhor Ator Coadjuvante" (in Portuguese). Academia Brasileira de Cinema. Archived from the original on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- "Finalistas 2003: Melhor Atriz Coadjuvante" (in Portuguese). Academia Brasileira de Cinema. Archived from the original on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- "Finalistas 2003: Melhor Direção de Arte" (in Portuguese). Academia Brasileira de Cinema. Archived from the original on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- "Finalistas 2003: Melhor Figurino" (in Portuguese). Academia Brasileira de Cinema. Archived from the original on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- "Finalistas 2003: Melhor Maquiagem" (in Portuguese). Academia Brasileira de Cinema. Archived from the original on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- "Finalistas 2003: Melhor Trilha Sonora" (in Portuguese). Academia Brasileira de Cinema. Archived from the original on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- Susman, Gary (3 December 2003). "Here are the Independent Spirit Award nominees". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- Grimm, Bob (8 January 2004). "Las Vegas Film Critics Society 2003 Winners". News & Review. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- Kamzan, Josh (3 March 2004). "Pic 'Masters' sound kudos". Variety. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- Rooney, David (15 December 2003). "Gotham crix crown 'King' as best film". Variety. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- "Prism Awards honor actors for portrayals". Deseret News. 1 May 2004. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- Maldonado, Ryan (17 December 2003). "Satellites pix picked". Variety. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- "The Critics' Choice". Entertainment Weekly. 9 January 2004. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- Kelly, Brendan (17 December 2003). "Toronto crix speak up for 'Translation'". Variety. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- Tillson, Tamsen (15 September 2002). "A 'Whale' of a tale in Toronto". Variety. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- Gonzalez, Ed (27 August 2003). "Interview: Fernando Meirelles Talks City of God". Slant Magazine. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- Cheded, Farah (17 January 2018). "The Legacy of 'City of God' on Brazil's Favelas". FilmSchoolRejects. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- Bowater, Donna (6 August 2013). "City of God, 10 years on". BBC News. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: City of God (2002 film) |

- Official website (in Portuguese)

- City of God on IMDb

- City of God at AllMovie

- City of God at Box Office Mojo

- City of God at Rotten Tomatoes

- City of God at Metacritic