Manaus

Manaus (/mɑːˈnaʊs/; Portuguese: [mɐˈnaws, mɐˈnawʃ]) is the capital and largest city of the Brazilian state of Amazonas. It is the seventh-largest city in Brazil, with an estimated 2019 population of 2,182,763[2] distributed over a land area of about 4,401.97 square miles (11,401 km2). Located at the east center of the state, the city is the center of the Manaus metropolitan area and the largest metropolitan area in the North Region of Brazil by urban landmass. It is situated near the confluence of the Negro and Solimões rivers.

Manaus | |

|---|---|

| Município de Manaus Municipality of Manaus | |

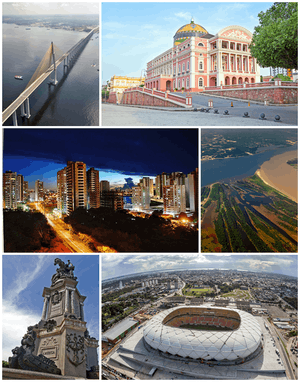

Top left, clockwise: Manaus–Iranduba Bridge; Teatro Amazonas; Meeting of Waters; Arena da Amazônia; Opening of the Ports Monument and view of the city. | |

Flag  Seal | |

| Nickname(s): A Paris dos Trópicos (The Paris of the Tropics); Mãe dos Deuses (Mother of the Gods) | |

| Motto(s): "A metrópole da Amazônia" (The metropolis of the Amazon) | |

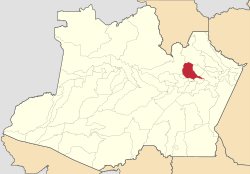

Location in the state of Amazonas | |

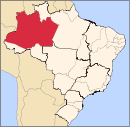

Manaus Location in Brazil | |

| Coordinates: 03°06′S 60°01′W | |

| Country | |

| Region | North |

| State | |

| Founded | October 24, 1669 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Arthur Virgílio Neto (PSDB) |

| Area | |

| • Metropolis | 11,401.092 km2 (4,401.97 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 427 km2 (165 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 92 m (302 ft) |

| Population (2019)[1] | |

| • Metropolis | 2,182,763 (7th) |

| • Density | 191.45/km2 (450.29/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,676,936 (11th) |

| Demonym(s) | Manauara, Manauense |

| Time zone | UTC−04:00 |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−04:00 |

| Postal Code | 69000-000 |

| Area code(s) | +55 (92) |

| Website | Manaus, Amazonas |

The city was founded in 1669 as the Fort of São José do Rio Negro. It was elevated to a town in 1832 with the name of "Manaus", an altered spelling of the indigenous Manaós peoples, and legally transformed into a city on October 24, 1848, with the name of Cidade da Barra do Rio Negro, Portuguese for "The City of the Margins of the Black River". On September 4, 1856 it returned to its original name.[3]

Manaus is located in the center of the world's largest rainforest, and home to the National Institute of Amazonian Research, being the most important center for scientific studies in the Amazon region and for international sustainability issues.[4] It was known at the beginning of the century, as "Heart of the Amazon" and "City of the Forest".[5] Currently its main economic engine is the Industrial Park of Manaus, a Free Economic Zone.[6] The city has a free port and an international airport. Its manufactures include electronics, chemical products, and soap; there are distilling and ship construction industries. Manaus also exports Brazil nuts, rubber, jute and rosewood oil. It has a cathedral, opera house, zoological and botanical gardens, an ecopark and regional and native peoples museums.[7]

The Solimões and Negro rivers meet just east of Manaus and join to form the Amazon River (using the Brazilian definition of the river; elsewhere, Solimões is considered the upper part of the Amazon[8]). Rubber made it the richest city in South America during the late 1800s. Rubber also helped Manaus earn its nickname, the "Paris of the Tropics". Many wealthy European families settled in Manaus and brought their love for sophisticated European art, architecture, and culture with them. Manaus was one of the twelve Brazilian host cities of the 2014 World Cup, as well as one of the five subsections of the 2016 Summer Olympics.

History

Etymology

The name Manaus comes from the native people called Manaós, which means Mother of the Gods.[9]

Early settlement of Manaus

The history of the European colonization of Manaus began in 1499 with the Spanish discovery of the mouth of the Amazon River. The Spanish then continued to colonize the region north of Brazil. Development continued in 1668–1669 with the building of the Fort of São José da Barra do Rio Negro by the Portuguese in order to ensure its predominance in the region, especially against the Dutch, at that time headquartered in what is today Suriname. The fort was constructed in rock and clay, with four cannon guarding the curtains.[10] It continued to function for more than 100 years. Next to the fort there were many indigenous mestizos, who helped in its construction and began to live in the vicinity.[10]

The population grew so much that in 1695, the missionaries (Carmelite, Jesuit, Franciscan) built a nearby chapel dedicated as Nossa Senhora da Conceição (Our Lady of the Conception), who in time became the patron saint of the city.[11] A Royal Charter of March 3 of 1755, created the captaincy of São José do Rio Negro, with capital in Mariuá (now Barcelos), but with the governor, Lobo D'Almada fearing a Spanish invasion, the seat went back to Lugar de Barra in 1791. Being located at the confluence of the Rio Negro and Amazon Rivers, it was a strategic point. On November 13 of 1832, Lugar da Barra was elevated to town status and named Manaus. On October 24 of 1848, under Law 145 of the Provincial Assembly of Para, it was renamed City of Barra do Rio Negro. On September 4 of 1856 the governor Herculano Ferreira Pena finally gave it the name "Manaus".[12]

Cabanagem

The Cabanagem was the revolt in which blacks, Native Americans and mestizos fought against the white political elite and took power in 1835. The Cabanagem reduced the population of the then state of Grão-Pará from about 100,000 to 60,000.[13] The involvement of rebels from the Upper Amazon (Manaus today) in what was originally a movement based in Belém was crucial for the birth of the current state of the Amazon. During the brief period of revolution, the Cabanos of the Upper Amazon, bands of rebels, roamed throughout the region, occupying Manaus twice, and in most settlements their arrival was greeted by the non-white population spontaneously joining their ranks, leading to a greater number of adherents to the movement. With that there was an integration of people in the region thus forming the state.[14]

Rubber boom

Manaus was at the center of the Amazon region's rubber boom during the late 19th century. For a time, it was "one of the gaudiest cities of the world".[15] Historian Robin Furneaux wrote of this period, "No extravagance, however absurd, deterred" the rubber barons. "If one rubber baron bought a vast yacht, another would install a tame lion in his villa, and a third would water his horse on champagne."[16] The city built a grand opera house, with vast domes and gilded balconies, and using marble, glass, and crystal, from around Europe. The opera house cost ten million (public-funded) dollars. In one season, half the members of one visiting opera troupe died of yellow fever.[17] The opera house, called the Teatro Amazonas, was effectively closed for most of the 20th Century. However it was used in scenes of the Werner Herzog film Fitzcarraldo (1982). After a gap of almost 90 years, it reopened to produce live opera in 1997 and is now attracting performers from all over the world.[18]

When the seeds of the rubber tree were smuggled out of the Amazon region to be cultivated on plantations in Southeast Asia,[Note 1] Brazil and Peru lost their monopoly on the product. The rubber boom ended abruptly, many people left its major cities, and Manaus fell into poverty. The rubber boom had made possible electrification of the city before it was installed on many European cities, but the end of the rubber boom made the generators too expensive to run. The city was not able to generate electricity again for years.[18]

Free Zone

In the 1960s during the establishment of the military dictatorship in Brazil, the newly installed government concerned about the "demographic gap in Brazil", began to introduce numerous projects in the interior of the country, especially in the Amazon region, with the introduction of the Manaus free trade zone in 1967,[19] and with the opening of new roads within the region, the city had a wide period of investments in financial and economic capital, both national and international, attracted by the tax incentives granted by the free zone, in this period, Manaus had enormous demographic growth becoming one of the most populous cities in Brazil.[20]

Recent events

Manaus was one of the host cities of the 2014 FIFA World Cup and one of the seats of some Olympic football games.[21] It was the only host city in the Amazon rainforest and the most geographically isolated, being further north and west than any of the other host cities. A massive prison riot occurred in January 2017, having begun in Manaus and later spreading to two additional cities in Brazil,[22] thus unleashing security problems within the country.[23][24]

Geography

.jpg)

The largest city in northern Brazil, Manaus occupies an area of 11,401 square kilometres (4,402 sq mi), with a density of 158.06 inhabitants/km2. It is the neighboring city of Presidente Figueiredo, Careiro, Iranduba, Rio Preto da Eva, Itacoatiara and Novo Airão.

Vegetation

Manaus is located in the middle of the Amazon Rainforest. The Amazon represents over half of the planet's remaining rainforests and comprises the largest and most species-rich tract of tropical rainforest in the world. Wet tropical forests are the most species-rich biome, and tropical forests in the Americas are consistently more species rich than the wet forests in Africa and Asia.[25] As the largest tract of tropical rainforest in the Americas, the Amazonian rainforests have unparalleled biodiversity. More than one-third of all species in the world live in the Amazon rainforest.[26]

Green areas

Despite being located in the Amazon, Manaus is densely developed and has few green areas in the city. The largest green areas are:

- Mindu Park, located in the center-south of the city, the district Park 10. The Park of Mindú, established in 1989, is one of the largest and most visited parks of the city.

- Bilhares Park, established in 2005, located in the south-central region of Manaus, in the neighborhood of Planalto (Plateau).

- Area of the green hill of Aleixo, created in the 1980s, located in the east of the city and one of the largest urban green areas.

- Sumaúma State Park, a state park located in the north of Manaus, in the New Town district. It is the smallest state park of the Brazilian Amazon Basin.

- Castanheiras Pied Tamarin Wildlife Refuge, a 95 hectares (230 acres) refuge created in 1982 to protect a population of endangered pied tamarins.

- Adolfo Ducke Forest Reserve, a biological reserve established in 1963, and covering an area of 100 square kilometres (10,000 hectares, 39 square miles). The Reserve is managed by INPA (Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazonia - National Institute for Amazon Research).

- Part of the Anavilhanas National Park, a 350,018 hectares (864,910 acres) conservation unit that was originally an ecological station created in 1981.[27]

- About 75% of the Rio Negro Left Bank Environmental Protection Area, a 611,008 hectares (1,509,830 acres) sustainable use conservation area created in 1995.[28]

- The 11,930 hectares (29,500 acres) Tupé Sustainable Development Reserve, created in 2005, about 25 kilometres (16 mi) west of the city.[29]

- The 86,601 hectares (214,000 acres) Rio Negro State Park South Section, created in 1995, about 40 kilometres (25 mi) by boat to the north west of the city.[30]

Climate

Manaus has a humid tropical rainforest climate (Af) according to the Köppen climate classification system, just wet enough in its driest month to not be a tropical monsoon climate, with average annual compensated temperature of 27.6 °C or 81.7 °F and high air humidity, with a rainfall index around 2,300 mm (90.6 in) annually. The seasons are relatively well defined with respect to rain: July to September is relatively dry, and December to May is very rainy. Thunderstorms are frequent everyday in the summer, but they can occur at any time of the year. There have been occasional occurrences of hail in the city.[31]

Due to the city's proximity to the equator, the heat is constant in the local climate. There are no cold days in winter, and rarely very intense polar air masses in the South-Central part of Brazil and in the south-west of the Amazon have some effect on the city, as occurred in August 1955. But although they are rare, they influence the climate, causing the temperature to drop to 18 °C (64.4 °F) or below.[32] The proximity to the forest usually avoids extremes of heat and makes the city wet.[33]

According National Institute of Meteorology (INMET), the highest temperature registered in the city was 39 °C or 102.2 °F, in 2015 and the lowest was 12 °C or 53.6 °F in 1989.

On November 26, 2009, a case of acid rain was recorded in Manaus. Air pollution, caused in large part by the accumulation of smoke from burning, associated with the carbon dioxide emitted by cars, was the cause of this phenomenon. Although the incidence of acid rain is common in some Brazilian capitals where there is a great concentration of cars, in Manaus and other cities of Amazonas the situation is aggravated by the prolonged period of drought with the smoke from forest fires.[34]

| Climate data for Manaus (1981–2010, extremes 1872–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 37.0 (98.6) |

37.8 (100.0) |

36.2 (97.2) |

35.4 (95.7) |

34.7 (94.5) |

34.9 (94.8) |

35.7 (96.3) |

37.6 (99.7) |

38.3 (100.9) |

38.1 (100.6) |

38.2 (100.8) |

37.3 (99.1) |

38.3 (100.9) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 30.9 (87.6) |

30.8 (87.4) |

30.9 (87.6) |

31.0 (87.8) |

31.1 (88.0) |

31.4 (88.5) |

32.1 (89.8) |

33.1 (91.6) |

33.5 (92.3) |

33.4 (92.1) |

32.6 (90.7) |

31.7 (89.1) |

31.9 (89.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 26.3 (79.3) |

26.3 (79.3) |

26.3 (79.3) |

26.4 (79.5) |

26.6 (79.9) |

26.7 (80.1) |

27.0 (80.6) |

27.6 (81.7) |

28.0 (82.4) |

28.0 (82.4) |

27.6 (81.7) |

26.9 (80.4) |

27.0 (80.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 23.1 (73.6) |

23.1 (73.6) |

23.2 (73.8) |

23.2 (73.8) |

23.4 (74.1) |

23.0 (73.4) |

23.1 (73.6) |

23.4 (74.1) |

23.7 (74.7) |

23.9 (75.0) |

23.7 (74.7) |

23.5 (74.3) |

23.4 (74.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 18.5 (65.3) |

18.0 (64.4) |

19.0 (66.2) |

18.5 (65.3) |

14.3 (57.7) |

17.0 (62.6) |

12.1 (53.8) |

18.0 (64.4) |

20.0 (68.0) |

19.4 (66.9) |

18.3 (64.9) |

19.0 (66.2) |

12.1 (53.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 287.0 (11.30) |

295.1 (11.62) |

300.0 (11.81) |

319.0 (12.56) |

246.9 (9.72) |

118.3 (4.66) |

75.4 (2.97) |

64.3 (2.53) |

76.3 (3.00) |

104.1 (4.10) |

169.2 (6.66) |

245.6 (9.67) |

2,301.2 (90.60) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 19 | 18 | 19 | 18 | 16 | 11 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 8 | 11 | 15 | 155 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 86.4 | 86.0 | 86.9 | 86.8 | 85.6 | 83.1 | 80.2 | 78.4 | 77.2 | 78.1 | 80.7 | 84.2 | 82.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 112.7 | 93.4 | 95.8 | 107.3 | 144.2 | 186.8 | 218.5 | 215.7 | 183.8 | 158.1 | 140.0 | 118.5 | 1,774.8 |

| Source 1: Brazilian National Institute of Meteorology (INMET) (climatological normals from 1981-2010;[35] (temperature extremes: 1961-present).[36][37] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Meteo Climat (record highs and lows)[38] | |||||||||||||

Hydrology

The urban area covers all or part of four river basins, all tributaries of the Rio Negro. The São Raimundo and Educandos streams are completely contained in the city. The Tarumã Açu forms the western boundary of the city in its lower reaches, and is fed by several tributaries that originate in the Ducke Reserve and run through the north and west of the city. The Puraquequara forms the east boundary of the urban area in its lower section.[39]

Demographics

According to the IBGE, in 2019 there were 2,182,763 people residing in the city, and 2,676,936 people in the Metropolitan Region of Manaus. The population density was 191.45 inhabitants per square kilometre (495.9/sq mi).

| Racial composition | 2000[40] |

|---|---|

| Mixed race | 63.93% |

| White | 31.88% |

| Black or African Brazilian | 2.43% |

| Asian or Amerindian | 0.87% |

- Total population: 2,145,444 inhabitants (87% urban, 13% rural, 52.07% women and 47.93% men)

- Population density: 158,06 inhabitants per square km

Manaus is the seventh largest city in Brazil, after São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Salvador, Brasilia, Fortaleza and Belo Horizonte.

The city's population growth is above the national average, and 10% above the average for the capital (Brasilia). Most of the population is located in the North and East regions of the city, and the New Town (northern area) the neighborhood is the most populous, with more than 260,000 residents.

According to the results of the last census, the city's population increased from 343,038 inhabitants in 1960 to 622,733 in 1970. By 1990 the population grew to 1,025,979 inhabitants, increasing its density to 90.0 inhabitants / km2.

According to a 2013 genetic study, the ancestry of the inhabitants of Manaus is 45.9% European, 37.8% Native American and 16.3% African.[41]

Religion

The city has been influenced by Catholicism since the time of European colonialism, and the majority of Manauenses are Catholic – there are nevertheless dozens of different Protestant denominations in the city. Judaism, Candomblé, Islam and spiritualism, among others, are also practised.[10] The city's Catedral Metropolitana Nossa Senhora da Conceição is the seat of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Manaus.

The city has a very diverse presence of Protestant or Reformed faiths, such as the Presbyterian Church, Calvary Chapel, For Christ International Church of Grace of God, Pentecostal Church of God in Brazil, Methodist Church, the Anglican Episcopal Church, the Baptist Church, an Assembly of God Church, the Seventh-day Adventist Church, the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God, and the Jehovah's Witnesses among others. These churches are experiencing considerable growth, mainly in the outskirts of the city. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints also has a large presence, with a LDS temple having been built in the city, the 6th in Brazil.[42]

Districts and regions

Metropolitan region

The Metropolitan Region of Manaus (RMM) is a metropolitan area that comprises eight cities of the Amazonas state, but without conurbation.

Regions

Manaus is divided into seven regions: North, Southern, Central-South, East, West, Mid-West and Rural area. The eastern region of the city is the most populated, with approximately 600,000 inhabitants (2007).[43] The northern region of the city has had the highest rate of population growth in recent years, and has the largest neighborhood of the city, the Nova Cidade neighborhood. The Center-South region has the highest per capita income.[44] The Eastern Zone is known for having a large number of hills.

Neighborhoods

- See also: List of bairros in Manaus

The first neighborhood (bairro) established in Manaus was Educandos. From there, other areas of the city began to be occupied, with the arrival of migrants from other regions of Brazil.

Manaus has the largest neighborhood of Latin America, the neighborhood of Cidade Nova, which has 264,449 inhabitants, but it is estimated that the population exceeds 300,000 inhabitants. Cidade Nova is larger than all the cities inside the Amazonas state.[45] With the permanence and the strengthening of Free Economic Zone of Manaus, the city began to receive investments and constant migration of people from many parts of the state and northern Brazil.

The wealthiest neighborhood in Manaus is Adrianópolis, located in the Central-South Area of the city. Downtown Manaus is located in the Southern area of the city, next to Rio Negro River. After years of development, the historical center has been neglected by the authorities and it has become an area mostly for commerce and poor housing. There is a plan to restore the city centre to its former glory by removing beggars and irregular sellers from sidewalks and by doing that provide more safety for tourists and locals who are trying to walk in the historical areas of the city. All these plans were prompted by the 2014 World Cup.

Economy

Manaus is the sixth largest economy in Brazil. According to IBGE in 2014, its GDP was R$67,5 billion.[46] The per capita income for the city was R$33,446.[47] Although the main industry of Manaus through much of the 20th century was rubber, its importance has declined. Given its location, fish, wild fruits like Açaí and Cupuaçu, and Brazil-nuts make up important trades, as do petroleum refining, soap manufacturing, and chemical industries. Over the last decades, a system of federal investments and tax incentives has turned the surrounding region into a major industrial center (the Free Economic Zone of Manaus).

Manaus sprawls, but the center of town, the Centro where most of the hotels and attractions are located, rises above the river on a slight hill. As the largest city and a major port on the river, Manaus is commercial. Local industries include brewing, shipbuilding, soap manufacturing, the production of chemicals, computers, motorcycles and petroleum refining of oil brought in by barge and tourism.[48][49]

The mobile phone companies LG, Nokia, Samsung, Siemens, Sagem, Gradiente and BenQ-Siemens operate mobile phone manufacturing plants in Manaus.[50][51] Plastic lens manufacturer Essilor also has a plant here. The Brazilian sport utility vehicle manufacturer Amazon Veiculos is headquartered in Manaus.[52] Two airlines, MAP Linhas Aéreas and Manaus Aerotáxi, have headquarters on the grounds of Eduardo Gomes International Airport in Manaus.[53][54]

Free Trade Zone

The initial idea of a Free Trade Port in Manaus, came from Deputy Francisco Pereira da Silva and was subsequently formalized by Law No. 3.173 on June 6, 1957. The project was approved by the National Congress on October 23, 1951 under No. 1.310 and regulated by Decree No. 47.757 on February 2, 1960. It was then amended by rapporteur Maurício Jopper, engineer, who by agreement with the original author, justified the creation of a Free Trade Zone instead of a Free Trade Port.

For the first ten years the ZFM (Manaus Free Trade Zone) was located in a warehouse rented from Manaus Harbour, in the Port of Manaus, and relied on federal funds. It was perhaps due to this lack of its own resources that there was little credibility in the project. On February 28, 1967, President Castello Branco signed Decree-Law No. 288, which redefined the Manaus Free Trade Zone in more concrete terms. The new Decree-Law stipulated that the Manaus Free Trade Zone would have a radius of 10 km (6.2 mi) with an industrial center as well as an agricultural center and that these would be given the economic means to allow for regional development in order to lift the Amazon out of the economic isolation that it had fallen into at that time.

On August 28, 1967, the Manaus Free Trade Zone Authority, SUFRAMA, was created. SUFRAMA is an independent body with its own legal status and assets and having financial and administrative autonomy. Tax incentives and the subsequent complementary legislation created comparative advantages in the region with respect to other parts of the country and as a result the Manaus Free Trade Zone attracted new investment to the area. These incentives constituted tax exemptions administered federally by SUFRAMA and SUDAM.

Government and politics

- See also: List of mayors of Manaus, List of aldermen of Manaus, and Câmara Municipal de Manaus

There is a prison, Anisio Jobim Penitentiary Complex.[55]

Education, science and technology

Manaus has research centers, technology and public and private universities.

- Federal University of Amazonas - Universidade Federal do Amazonas;

- University of the State of Amazonas - Universidade do Estado do Amazonas;

- National Institute of Amazonian Research - Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia;

- Sidia Institute of Science and Technology - Sidia Instituto de Ciência e Tecnologia;

- Federal Institute of Education, Science and Technology - Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia do Amazonas;

- Centro Universitário do Norte - UNINORTE;

- Lutheran University of Brazil - Universidade Luterana do Brasil;

- Centro de Educação Integrada Martha Falcão;

- Unilasalle - Faculdade La Salle;

- Universidade Nilton Lins;

- Centro Universitário de Educação Superior do Amazonas - CIESA;

- Escola Superior Batista do Amazonas;

- Faculdade Boas Novas;

- Faculdade Metropolitana de Manaus;

- Universidade Paulista.

Transportation

Airports

Eduardo Gomes International Airport is the airport serving Manaus. The airport has two passenger terminals, one for scheduled flights and the other for regional aviation. It also has three cargo terminals.

Eduardo Gomes International Airport is Brazil's third largest in freight movement,[56] handling the import and export demand from the Manaus Industrial Complex. For this reason, Infraero invested in construction of the third cargo terminal, opened on December 14, 2004. TAM Airlines also inaugurated their own cargo terminal near the airport in 2008, which claims to be their largest cargo terminal in Brazil. The country's major dedicated freight route is between Manaus and Viracopos International Airport, which is operated by wide-body jets. Other freight routes include North America and Europe.

The passenger terminal had been fully refurbished and expanded in time for the 2014 FIFA Football World Cup, which held 4 games in Manaus. The airport currently operates daily international flights to Miami and Orlando, United States, by American Airlines and LATAM Airlines Brasil, to the city of Panama, by Copa Airlines and to Barcelona, Venezuela, by Avior Airlines. The airport has direct flights to all major airports in Brazil, operated by the three major carriers: Gol Transportes Aéreos, TAM Airlines and Azul Brazilian Airlines. The airport's IATA code is MAO.

Manaus Air Force Base, a base of the Brazilian Air Force is at the former Ponta Pelada Airport.

Apart from the Eduardo Gomes International Airport and Ponta Pelada Airport, Manaus still has an operational airstrip used by small propeller aircraft and helicopters about 6 kilometres (4 miles) north of the city centre, simply known as the "Aeroclube" ("airclub"). On Sundays, it is used for parachuting and where flying classes can be hired. Due to the fact that it is surrounded by residential areas, and has a recent history of crashes, it is under constant pressure to be moved.

Highways

There are two federal highways that intersect Manaus. There is a paved road heading North (BR-174) connecting Manaus to Boa Vista, capital of the State of Roraima and to Venezuela. Strictly speaking, Manaus is connected by road to the rest of Brazil, as it is possible to drive continuously from Manaus into Venezuela, and then reenter Brazil through the BR-364 in the state of Acre and its capital, Rio Branco, therefore passing through the countries of Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. As such a route is impractical for most motorists, the vast majority of transportation to and from Manaus is by boat or plane, except for journeys to Roraima. The Independent noted that "there are still no roads to Manaus" from the rest of the country.[57]

The BR-319 heads South connecting Manaus to Porto Velho, the state capital of Rondônia. However, the access to this highway requires a ferry crossing to Careiro, across the Rio Negro and River Amazon, which takes about 40 minutes, and then is only paved for about another 100 km (62 mi) to Castanho. After that, the highway is not paved, and can not be used. Various governments have promised to recover this land-link with the rest of the country, but environmental issues, high costs and complicated logistics have impeded any progress so far.

The two major state highways are the AM-010 and the AM-070. The AM-010 heads east, to Itacoatiara, Amazonas at the banks of the River Amazon, which is the third largest city of the state. The AM-070 heads south, starting on the other side of the new bridge spanning the Rio Negro at Manaus, and reaching Manacapuru which lies at the banks of the Solimoes River, also known as the upper River Amazon, and which is the fourth largest city of the state. Both roads are paved and operate all year round.

Port

Ships dock at the main port in Manaus directly downtown on the banks of the Negro River. The terraced city is home to a network of bridged channels that divide it into several compartments. Several mobile phone companies have manufacturing plants in the port area, and other major electronics manufacturers also have plants there. Major exports going through the port include Brazil nuts, chemicals, petroleum, electrical equipment, and forest products.

Taxis

Regular Manaus taxis are white and can be stopped anywhere. They're organised into separate cooperatives, each with their own contact phone numbers. All taxis are metered, which doesn't necessarily mean the meter will be used.

The 'especial' taxi cars are typically black and of a higher quality than the white taxis, and will charge a fixed rate for all journeys or daily hire. Most can only be booked locally; however, the reputable Brazil Airport Transfers[58] has recently started providing airport transfer and general transportation services in Manaus.

Bus

The bus system in Manaus is quite extensive and there are buses and vans that go to most destinations, including the popular tourist destinations. There is a very simple bus website that permits planning of routes.

Events and holidays

The annual calendar of festivals in Manaus starts in late February/early March. The Manaus carnival (carnaval) celebrations are a good start to upcoming events and include traditional processions and samba dancing at the Sambódromo in the Centro de Convenções (Convention Centre). May is a popular time to pay a visit to Manaus, since the city hosts both the Ponta Negra Music and the Amazonas de Opera festivals during this month. Staged at the Teatro Amazonas, the Opera Festival lasts around three weeks and usually runs into early June. The Floclorico do Amazonas (Amazonas Folklore Festival) is in June, and this has grown to become a major event, involving a huge array of folk dancing and music, culminating in the Procissao Fluvial de São Pedro (St. Peter River Procession), when hundreds of riverboats sail along the Rio Negro, honouring the patron saint of fishermen.

October 24 was the day in 1848 that Manaus legally became a city. This anniversary is always cause for a party, culminating in fireworks at the end of the day. In November is the week-long Amazonas Film Festival, with films and documentaries often emphasising ecology, ethnology and human relationships.[59]

- February – Amazonas Carnival – samba schools parade at the "sambódromo" in the Convention Center

- May – Ponta Negra's Music Festival

- May - Amazonas Opera Festival

- June – Amazonas Folklore Festival

- June 29 – São Pedro Fluvial Procession

- July - Amazonas Jazz Festival

- September 5 - Elevation of Amazonas to the category of Brazilian Province

- October 24 – Anniversary of Manaus

- December 31 – Ponta Negra's New Year's Eve Party

Sights and attractions

Because of Manaus' location next to the Amazon rainforest, it attracts a substantial number of Brazilian and foreign tourists, who come to see wildlife on land and in the rivers. It is also home to one of the most endangered primates in Brazil, the pied tamarin.

Tour boats leave Manaus to see the Meeting of the Waters, where the black waters of the Negro River meet the brown waters of the Solimoes River, flowing side by side without mixing for about 9 km (6 mi). Visitors can also explore river banks and "igarapes", swim and canoe in placid lakes, simply walk in the lush forest or stay at hotels in the jungle.

About 18 km (11 mi) from downtown is Ponta Negra beach, a neighbourhood that has a beachfront and popular nightlife area.[61] A luxurious hotel is located at the west end of Ponta Negra; its zoo and orchid greenhouse as well as preserved woods and beach are open for public visits.

The Mercado Adolpho Lisboa, founded in 1882, is the city's oldest marketplace, trading in fruit, vegetables, and especially fish. It is a copy of the Les Halles market of Paris.[62] Other interesting historical sites include the customs building, of mixed styles and medieval inspiration; the Rio Negro Palace cultural center; and the Justice Palace, right next to the Amazonas Opera House.

Manaus has also many large parks with native forest preservation areas, such as the Bosque da Ciência and Parque do Mindú. The largest urban forest in the world is located within the Federal University of Amazonas, which was founded on January 17, 1909 and is the oldest federal university in Brazil.

Manaus also has several Malls such as Manauara Shopping, Amazonas Shopping Center, Millennium Shopping, Shopping Ponta Negra, Studio 5 Festival Mall, Shopping Cidade Nova, Manaus Plaza Shopping, Shopping Sao José and other small Shopping Areas. Most of these malls include large food courts and movie theaters.

The city's cultural calendar throughout the year includes the Opera, Theater, Jazz and Cinema festivals, as well as Boi Manaus (usually held around Manaus' anniversary on the 24th of October), which is a great celebration of Northern Brazilian culture through Boi-Bumbá music.

Amazonas Opera House

The Amazonas Opera House, inaugurated in 1896, has 700 seats and was constructed with bricks brought from Europe, French glass and Italian marble. Several important opera and theater companies, as well as international orchestras, have already performed there. The Theater is home to the Amazonas Philharmonic orchestra which regularly rehearses and performs there along with choirs, jazz bands, dance performances and more.[63]

Parks

Ponta Negra Cultural, Sport and Leisure Park

Ponta Negra beach, located 13 km (8.1 mi) from downtown Manaus, is one of the city's most important tourist attractions. It also has an amphitheater with capacity for 15.000 people.

Adolpho Ducke Botanical Garden

The Adolpho Ducke Botanical Garden, inside a 100 square kilometres (39 sq mi) ecological reserve, holds a huge number of plant and animal species.[64]

Mindu Municipal Park

It is located in an urban area, in the November 10 Park district. It was created in 1992 to be an area of ecological interest. It covers an area of 330,000 m2 (3,552,090 sq ft) of forest remaining from the Township, and is used for scientific, educational, cultural and tourist activities. It is one of the last habitats for the pied tamarin, a species of monkey that only inhabits the Manaus region and is considered to be at high risk of extinction. It is possible to walk through four distinct ecosystems in the park: land covered by secondary growth, firm ground brush, sandbanks and degraded areas that were illegally cleared in 1989. It also has an amphitheater for 600 people, gardens planted with medicinal and aromatic herbs, orchid nursery, aerial trails and signs aiming to develop environmental education programs.[65]

Public swimming areas

The Tarumã, Tarumãzinho and Cachoeira das Almas bayous (branches of rivers), located near the city, are leisure spots for the population on weekends. Manaus has several public swimming areas that are being remodeled and urbanized lately. There are also many private clubs that can be visited.

Meeting of Waters

This natural phenomenon is caused by the confluence of the Negro River's dark water and the Solimões River's muddy brown water that come together to form the Amazonas River. For 6 km (3.7 mi) or more, both rivers waters run side by side without mixing. The reason for this is not clear, although it is likely that the main factors are differences in the speed of the current, the volumes of water and the different densities of the two rivers. It is not thought that other differences between the two rivers (temperature and acidity) affect the mixing process significantly.[66] The Negro River flows approximately 2 km/h (1.2 mph) at 28 °C (82 °F), while the Solimões River flows 4 to 6 km/h (2.5 to 3.7 mph) at 22 °C (72 °F).[67]

CIGS Zoo

The zoo is open to the public. It is managed by the Brazilian Army and has approximately 300 species of animals from the Amazon fauna.[68]

Beaches and waterfalls

For outings to beaches and parks situated near the city, it is often necessary to use boats. The beaches are formed right after the river water level starts dropping, which lasts from August to November. Starting in December, as the river rises, the waters invade the sand and the woods on the banks. The Paricatuba Waterfall, located on the right bank of the Negro River, along a small tributary, is formed by sedimentary rocks, surrounded by abundant vegetation. Access is by boat. The best time to visit is from August to February. Love Cascade located in the Guedes bayou, with cold and crystal clear water, is accessible only by boat and, then, hiking through the forest.

Tupé Beach is approximately 34 km (21 mi) from Manaus. This beach is well frequented by bathers on holidays and weekends. It is accessible only by boat. Moon Beach is located on the left bank of the Negro River, 23 km (14 mi) from Manaus. It is accessed only by boat. The beach is shaped like a crescent moon and is surrounded by rare vegetation. Lion waterfall is located on km 34 of the AM-010 highway (Manaus-Itacoatiara).

Sports

Football

The leader club in Manaus is the Nacional Futebol Clube, founded on January 13, 1913, and called "Leão da Vila". Participant of the serie A (first division) for several times between 1970 and 1990. Nacional is 40-times state champion, the great state champion in Amazon state, and one of the greatest state champion in Brazil, and is the best amazonian football club ranked in the CBF ranking, the official Brazilian football entity.

Other club is the Atlético Rio Negro Clube, called "Galo da Praça da Saudade" (Remembrance Square Rooster) or "Barriga Preta" club (Black Belly), also founded in 1913, but in November, which is the second largest holder of state titles, and the National Fast Club, the Tricolor of the Boulevard" or "roll", founded in the early 40 years from a dissident's National Football Club, which has won six state championships, in addition to being Northern Region champion and North-Northeast Championship runner-up in 1970.

There is also San Raimundo Sports Club – the Typhoon Hill (Tufão da Colina), founded on November 18, 1918, participant of the Series B (2nd division) of the Brazilian Championship until 2006, when it was demoted. It is a 7-times states champion, 3-times North Cup champion.

2014 FIFA World Cup

Manaus was chosen in 2009 to be a host city for the 2014 FIFA World Cup, after a competition to represent the North Region of Brazil with neighboring Pará state capital, Belém.

Manaus was restructured in order to host such a big event. A new airport was built, streets throughout the city were repaved and new and improved sidewalks were built. The communications infrastructure of the city was improved with 4G networks installed by the biggest mobile phone carriers in Brazil.

The Vivaldão, previously the largest stadium in Manaus, was inaugurated in 1970 by the Brazilian national team in their last game in the country before they headed to their victorious 1970 in Mexico. It was demolished to be replaced by the 44,000 seater Arena Amazônia for the 2014 World Cup.[69]

The first 2014 World Cup match held in Manaus was England vs Italy on June 14. The second match was Cameroon vs Croatia on June 18, to be followed by USA vs Portugal on June 22. The last was Honduras vs Switzerland on June 25. Manaus, known for its intense heat and humidity, was the site of the World Cup's first ever official water break on June 22 in the match between Portugal and the United States.

Brazilian jiu-jitsu

Manaus is the origin of several world-champion Brazilian jiu-jitsu black belts, mixed martial artists and submission grapplers. Champions such as Fredson Paixão, Wallid Ismail, Saulo Ribeiro, Cristiane De Souza, Alexandre Ribeiro, Ronaldo Souza, and Bibiano Fernandes hail from Manaus. Brazilian jiu-jitsu is a major component of MMA (mixed martial arts). José Aldo (born September 9, 1986) is a black-belt in Brazilian jiu-jitsu and notable UFC fighter. Aldo defeated Mike Brown at WEC 44 to win the title and has since successfully defended his WEC title against Urijah Faber & Manvel Gamburyan. He later became the UFC Featherweight champion, with title defenses against such notable fighters as Mark Hominick and Kenny Florian.

International relations

Twin towns – sister cities

Manaus is twinned with:

|

|

Notable people

- Adrino Aragão - short story writer

- Elisio de Albuquerque - film actor

- Fredson Paixão - 4X BJJ world champion, UFC & WEC Featherweight (MMA)

- José Aldo - UFC featherweight champion

- Helder Agostini - actor

- Arthur Autran - screenwriter, producer, director

- Gabriel Azevedo - television actor

- Djalma Limongi Batista - director, cinematographer, producer

- Wirlesson Falcão - youth ambassador to the U.S.

- Diego Brandão - Ultimate Fighter Season 14 featherweight winner

- Antonio Calmon - screenwriter

- Vinicius Cantuária - bossa nova musician

- Violeta Cavalcanti - actress

- Luiz de Miranda Correa - screenwriter, director, producer and composer

- Cristiane De Souza - 3X BJJ world champion, MMA competitor

- Bibiano Fernandes - jiu-jitsu competitor

- Oscar Felipe - actor

- Marcelo Gomes - principal dancer with American Ballet Theatre

- Milton Hatoum - writer

- Wallid Ismail - jiu-jitsu black belt, UFC competitor

- Darcyana Moreno Izel - film/television director, producer and animator

- Roberto Kahane - film director

- Francisco Lima Govinho - football player

- Cesar Manaus - actor

- Priscilla Meirelles - Miss Brazil Earth 2004, Miss Earth 2004

- Cosme Alves Neto - actor

- Olga Nobre - actress

- Cristiano Moraes Oliveira - football player

- Fábio Pereira de Oliveira - known as Fábio Bala, Brazilian football player

- Jefferson Peres - politician

- Antônio Pizzonia - Formula 1 and Champion Car World Series driver

- Eliana Printes - MPB singer and composer

- Larissa Ramos - Miss Brazil Earth 2009, Miss Earth 2009

- Saulo Ribeiro - jiu-jitsu world champion

- Xande Ribeiro - jiu-jitsu world champion

- Carlos Frederico Rodrigues - screenwriter, director, producer and composer

- Malvino Salvador - actor

- Cláudio Santoro - conductor and composer of classical music

- Márcio Souza - writer and novelist

- Ronaldo Souza - jiu-jitsu world champion, ADCC Submission Wrestling World Championship and UFC competitor

- Mister No - comic book character

Notes

- For an account, see The Thief at the End of the World: Rubber, Power, and the Seeds of Empire, by Joe Jackson.

References

- "IBGE discloses municipal population estimates for 2019. Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) (August 28, 2019)". Ibge.gov.br. Archived from the original on August 28, 2019. Retrieved August 28, 2019.

- IBGE releases Population Estimates of municipalities for 2019 Archived 2019-08-28 at the Wayback Machine(in English)

- About Manaus Archived 2009-07-01 at the Wayback Machine

- "National Institute for Amazonia Research (INPA)". eubon.eu. Archived from the original on 2019-07-14. Retrieved 2019-07-14.

- Heart of The Amazon and City of the Forest Archived 2009-06-14 at the Wayback Machine

- "Manaus, Brazil - Amazon River Cruise Ship Port of Call". TripSavvy. Archived from the original on 2018-09-11. Retrieved 2019-02-05.

- "Manaus - Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on 2019-02-07. Retrieved 2019-02-05.

- "Where Does the Amazon River Begin?". National Geographic News. 15 February 2014. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- "Manaus" (PDF). ICMBio. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- "About Manaus". www.calvarymanaus.com. Archived from the original on 2014-01-28. Retrieved 2014-01-21.

- "creyete.com". creyete.com. Archived from the original on 2011-07-08. Retrieved 2009-07-22.

- Manaus History Archived 2014-02-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Renato Cancian. "Cabanagem (1835–1840): Uma das mais sangrentas rebeliões do período regencial". Universo Online Liçao de Casa (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 2 November 2007. Retrieved 12 November 2007.

- Sampaio, Patricia. "Crônicas de gente pouco importante IV: Bernardo de Sena – negro, cabano e "prefeito"". Amazônia Real. Archived from the original on 23 January 2017. Retrieved 8 May 2017.

- David Grann. The Lost City of Z. Random House. New York: 2009. Page 87.

- Robin Furneaux. The Amazon: the Story of a Great River. London: Hamish Hamilton, 1969. Page 153.

- Grann 87.

- "Christina Lamb, "A night at the opera - and 14 days on the Amazon to get there", The Sunday Telegraph, London, 17th June 2001". Archived from the original on 2017-06-20. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

- Presidency of the Republic (February 28, 1967). "Decree-Law. 288 of 28 February 1967" (in Portuguese). Civil House; Subheading for Legal Affairs. Archived from the original on 5 July 2017. Retrieved June 21, 2017.

- "Panorama Manaus". cidades.ibge.gov.br (in Portuguese). IBGE- (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics). Archived from the original on September 1, 2017. Retrieved June 21, 2017.

- "In the Brazilian Rain Forest, 'a White Elephant, a Big One'". The New York Times. August 16, 2016. Archived from the original on February 22, 2017. Retrieved May 15, 2017.

- "Riot Police Try to Quell Continuing Violence in Brazilian Prison". By DOM PHILLIPS. The New York Times. January 19, 2017. Archived from the original on January 21, 2017. Retrieved March 23, 2017.

- BRUNA CHAGAS in collaboration with Folha, in Manaus; RUBENS VALENTE special envoy for Folha in Manaus. (January 3, 2017). "Prison fight between gangs leads to 56 deaths in Manaus". FOLHA. Archived from the original on February 7, 2017. Retrieved February 3, 2017.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- By SIMON ROMERO (January 2, 2017). "Riot by Drug Gangs in Brazil Prison Leaves at Least 56 Dead". Archived from the original on January 8, 2017. Retrieved February 6, 2017.

- Turner, I.M. 2001. The ecology of trees in the tropical rain forest. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-80183-4

- "Biomes - Conserving Biomes - WWF". World Wildlife Fund. Archived from the original on 2013-04-15. Retrieved 2019-02-05.

- PARNA de Anavilhanas (in Portuguese), ISA: Instituto Socioambiental, archived from the original on 2016-05-06, retrieved 2016-04-30

- APA Margem Esquerda do Rio Negro (in Portuguese), ISA: Instituto Socioambiental, archived from the original on 2019-01-23, retrieved 2016-06-28

- Fabio Pontes (23 September 2016), "População tradicional da RDS do Tupé vive conflito ambiental no Amazonas", Amazônia Real (in Portuguese), archived from the original on 13 October 2016, retrieved 2016-10-12

- PES do Rio Negro Setor Sul (in Portuguese), ISA:Instituto Socioambiental, archived from the original on 2017-02-21, retrieved 2016-06-24

- "Chuva de granizo atinge diversos pontos de Manaus" (in Portuguese). G1 Amazonas. 25 October 2011. Archived from the original on 23 February 2015. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- "Frente fria deve atingir Manaus e temperatura pode cair para 18°C" (in Portuguese). G1 Amazonas. 24 July 2013. Archived from the original on 23 February 2015. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- "Cidades do Amazonas - Manaus" (in Portuguese). Ache tudo e região. Archived from the original on 8 May 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- "Instituto de meteorologia registra chuva ácida em Manaus" (in Portuguese). Portal Amazônia. Archived from the original on 2013-04-26.

- "Normais Climatológicas Do Brasil 1981–2010" (in Portuguese). Instituto Nacional de Meteorologia. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- "BDMEP - Série Histórica - Dados Diários - Temperatura Mínima (°C) - Manaus". Banco de Dados Meteorológicos para Ensino e Pesquisa. Instituto Nacional de Meteorologia. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- "BDMEP - Série Histórica - Dados Diários - Temperatura Máxima (°C) - Manaus". Banco de Dados Meteorológicos para Ensino e Pesquisa. Instituto Nacional de Meteorologia. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- "Station Manaus" (in French). Meteo Climat. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- Rovere, Ana Lúcia Nadalutti La; Crespo, Samyra; Velloso, Rui (2002), Projeto geo cidades: relatório ambiental urbano integrado: informe GEO: Manaus (PDF) (in Portuguese), Rio de Janeiro: PNUMA; Brasil. Ministério do Meio Ambiente. Secretaria de Qualidade Ambiental nos Assentamentos Humanos; Consórcio Perceria 21, p. 68, archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-02-02, retrieved 2016-06-28

- Síntese de Indicadores Sociais 2000 (PDF) (in Portuguese). Manaus, Brazil: IBGE. 2000. ISBN 85-240-3919-1. Archived from the original on 2011-06-14. Retrieved 2009-01-31.

- Dennis O'Rourke, University of Utah (20 September 2013). "Revisiting the Genetic Ancestry of Brazilians Using Autosomal AIM-Indels". PLoS ONE. Archived from the original on 25 July 2014. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- "Manaus Brazil Temple Is Dedicated". Mormon Newsroom. 2012-06-11. Archived from the original on 2019-06-30. Retrieved 2019-02-09.

- "East zone of Manaus". Archived from the original on 2016-09-23. Retrieved 2009-07-22.

- "Center-South region of Manaus". Archived from the original on 2011-07-15. Retrieved 2009-07-22.

- "Amazonas City Populations, Retrieved on June 20, 2012". Archived from the original on November 30, 2011. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

- "IBGE - Agência de Notícias". IBGE - Agência de Notícias. Archived from the original on 2019-02-08. Retrieved 2019-02-05.

- http://cod.ibge.gov.br/1U8VW

- "Manaus, Brazil". Gosouthamerica.about.com. 2012-04-09. Archived from the original on 2013-03-26. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- Terry Wade of Reuters (2006-09-30). "Jets collide, 155 feared dead". Courier Mail. Archived from the original on 2012-09-08. Retrieved 2011-03-04.

- "Nokia in Manaus". Archived from the original on 2007-08-17. Retrieved 2009-07-22.

- Siemens Archived 2012-12-17 at Archive.today

- "Pólo Industrial de Manaus". www.suframa.gov.br. Archived from the original on 2009-07-26. Retrieved 2009-07-22.

- Home page Archived 2016-12-11 at the Wayback Machine. Rico Linhas Aéreas. Retrieved on February 9, 2010.

- "Fale Conosco Archived 2010-01-30 at the Wayback Machine." Manaus Aerotáxi. Retrieved on October 13, 2009.

- "Brazil prison riots leave dozens dead, more than 100 inmates at large". ABC News (Australia). 2017-01-03.

- Cargo movement in International Airport of Manaus Archived 2009-10-07 at the Wayback Machine

- "England v Italy: Are they painting the Manaus pitch green?". The Independent. 12 June 2014. Archived from the original on 7 February 2019. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- "Brazil Airport Transfers". Archived from the original on 2018-11-22. Retrieved 2019-10-05.

- "Manaus Events and Festivals in 2014 / 2015: Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil". www.world-guides.com. Archived from the original on 2014-02-01. Retrieved 2014-01-20.

- "Manaus's opulent Amazon Theatre". The Guardian. 2015-04-14. Retrieved 2019-10-29.

- "Photos from Ponta Negra Beach - Manaus". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04.

- Manaus Archived 2014-02-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Facts - Amazon Theatre Archived 2009-04-06 at the Wayback Machine

- Adolpho Ducke Botanical Garden Archived 2007-03-04 at Archive.today

- "Parque do Mindú - Pontos Turísticos, Passeios e Diversões - Guia Manaus Mais". www.manausmais.com.br. Archived from the original on 2009-07-06. Retrieved 2009-07-24.

- Maguire, T. C., 2012. 'The Amazon Handbook' 2nd Ed., ISBN 978-0-9565741-2-1

- "Natural phenomenon of confluence". Archived from the original on 2007-03-04. Retrieved 2009-07-24.

- Zoo of Manaus Archived 2008-12-27 at Archive.today

- Vivaldão Stadium Archived 2014-01-21 at the Wayback Machine

- "LEI Nº 2.044, DE 16 DE OUTUBRO DE 2015" (PDF) (in Portuguese). Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 February 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- "Braga e Manaus reforçam cooperação estratégica" (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 20 August 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

Bibliography

External links

- Official website—(in Portuguese)

.tif.png)

.tif.png)

.jpg)