Brazilian Grand Prix

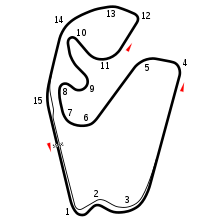

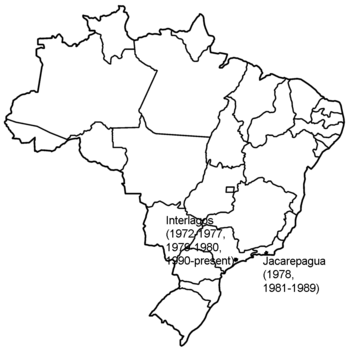

The Brazilian Grand Prix (Portuguese: Grande Prêmio do Brasil) is a Formula One championship race which is currently held at the Autódromo José Carlos Pace in Interlagos neighborhood, Socorro district, São Paulo.

| Autódromo José Carlos Pace (1990–present) | |

| |

| Race information | |

|---|---|

| Number of times held | 48 |

| First held | 1972 |

| Most wins (drivers) | |

| Most wins (constructors) | |

| Circuit length | 4.309 km (2.677 mi) |

| Race length | 305.879 km (190.064 mi) |

| Laps | 71 |

| Last race (2019) | |

| Pole position | |

| |

| Podium | |

| |

| Fastest lap | |

| |

History

Origins

Motor racing started in Brazil before World War II, with races on the 6.9-mile Gávea street circuit in Rio de Janeiro starting in 1934. In 1936 construction began on Brazil's first permanent autodrome in the São Paulo neighborhood of Interlagos and was finished in 1940. Brazil held Grands Prix during the early parts of WWII at Interlagos and Gavea. Interlagos, a circuit inspired in layout by the Roosevelt Raceway in the United States quickly gained a reputation as being a tough and demanding circuit with many challenging corners, elevation changes, a rough surface, and little room for error.

Formula One

Interlagos, São Paulo

A Brazilian Grand Prix was first held in 1972 at Interlagos, although it was not part of the Formula One World Championship. Typical of European motorsports at the time, this race was done as a test to convince the FIA if the Interlagos circuit and its organizers could capably hold a Grand Prix. Like most major circuits used for Grands Prix in Latin America such as the Hermanos Rodríguez Autodrome in Mexico City Interlagos was (and still is) located in the confines of a sprawling urban neighborhood in a very large city. The following year, however, the race was first included in the official calendar, and it was won by defending world champion and São Paulo native Emerson Fittipaldi. In 1974, Fittipaldi won again in rain soaked conditions, and the year after, another São Paulo native, Carlos Pace, won the race in his Brabham, followed by Fittipaldi. 1977 was won by Reutemann, but the drivers began complaining about Interlagos's very rough surface, and the event was then relocated for a year to the new Jacarepaguá circuit in Rio de Janeiro.

After a year in Rio, the race returned to Interlagos, now with new and upgraded facilities for the next two seasons; this race was won by Jacques Laffite to complete his and Ligier's conquest of the opening South American rounds in Argentina and Brazil. But the Interlagos surface was still very bumpy. The original arrangement from 1978 onwards was to alternate the Brazilian Grand Prix between the São Paulo and Rio circuits; the 1980 race was originally supposed to be held at Jacarepaguá but parts of that circuit (which was originally built on a swamp) were beginning to sink into the soft ground and the circuit disintegrated badly, so the 1980 Grand Prix was to be relocated to Interlagos. But by this time, the population of São Paulo had risen from 5 to 8 million over the space of 10 years; the area surrounding the track was becoming increasingly run-down and surrounding the circuit did not look good for Formula One, which thanks to worldwide television exposure was becoming something of a glamorous spectacle. Formula One was originally supposed to come back to Interlagos for the 1981 season after the track surface there would be repaved; it turned out that F1 came back a year too early. The drivers were dissatisfied with the safety conditions of the very bumpy 5-mile Interlagos circuit which had not been changed after the previous year's improvements. The ground-effect wing cars of that year had a tendency to bounce up and down thanks to the suction created by the cars' wing-shaped underbodies, and they were more stiffly suspended than before; so these fragile cars were barely tolerant of such a rough track and were very unpleasant to drive. The bad surface was so rough that the bumps caused mechanical problems for some cars. Also, the barriers and catch-fence arrangements were not adequate enough for Formula One. Jody Scheckter attempted to stop the race from going ahead but this did not work and the race ended up being won by Frenchman René Arnoux. With Formula One's more glamorous image being better suited to the more better-looking city of Rio de Janeiro, the F1 circus went back to Rio again and the circuit went on to host the 1980s turbo era.

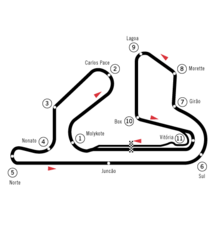

Jacarepaguá, Rio de Janeiro

In 1978 the Brazilian Grand Prix moved to Jacarepaguá in Rio de Janeiro. Argentine Carlos Reutemann dominated in his Ferrari, which was equipped with superior Michelin tyres. This proved to be the French company's first victory in Formula One. Reutemann was followed by home favorite Fittipaldi and defending champion Niki Lauda.[1]

After the emergence in 1980 of Rio de Janeiro racer Nelson Piquet, the decline of Interlagos and the retirement of Fittipaldi, Brazilian fans lobbied to host the Brazilian GP in Piquet's home town. The flat Jacarepaguá circuit, like Interlagos before it, proved to be extremely demanding: most corners were long and fast, some were slightly banked and the track had a very abrasive surface. Due to the FIA calendar, which invariably had the Brazilian GP at the beginning of the season thus in the Southern hemisphere summer and the tropical weather of Rio, most races were held under very high temperatures and high humidity. Due to all of those circumstances, Grands Prix at Rio were highly demanding and most drivers who won it were exhausted in the end.

In 1981, Carlos Reutemann disobeyed team orders to let his teammate Alan Jones by and took the victory; the following year Piquet finished 1st and Keke Rosberg finished 2nd but because of the FISA–FOCA war, Piquet and Rosberg were both disqualified for being underweight in post-race scrutineering, and the race victory was given to 3rd placed Alain Prost, who would go on to win at Jacarepaguá 4 more times (thus earning the nickname "the King of Rio"). The race also saw Italian Riccardo Patrese retire due to physical exhaustion (a very rare occurrence in F1, but quite common at Rio). Piquet won in 1983 and 1986, and the 1988 race was particularly notable, as up-and-coming star Ayrton Senna started from the pit-lane in his first race for McLaren; he began a furious charge that brought him up to second behind his teammate Prost; but he was disqualified for switching to his spare car after the parade lap had begun. The 1989 event was the last race at Jacarepaguá. It was won by British driver Nigel Mansell in his Ferrari, in the first Grand Prix won by a car with a semi-automatic gearbox, and it also saw German Bernd Schneider and American Eddie Cheever collide, and Cheever collapsed twice after he exited his car due to exhaustion.

Return to a new Interlagos

São Paulo native Ayrton Senna's success thus far in Formula One had city officials working hard to revamp the Interlagos circuit in a $15 million investment to shorten and smooth over the circuit. In 1990 the Grand Prix returned to a shortened Interlagos, where it has stayed since. The Interlagos circuit has created some of the most exciting and memorable races in recent Formula One history, and is regarded as one of the most challenging and exciting circuits on the F1 calendar.

The first race at the new Interlagos in 1990 was won by Alain Prost, who won his 40th career race (the most ever at that point in time) and his 6th Brazilian Grand Prix. It wasn't a popular win, as the events of the previous year's Japanese Grand Prix were still fresh in the minds of many Brazilians: Prost was seen as having been given the Drivers' title by FIA president Jean-Marie Balestre at Senna's expense after Senna was disqualified from that race in Japan. The Brazilian, a home favorite, finished 3rd in Brazil after leading much of the race but then hitting his backmarker ex-teammate Satoru Nakajima in a Tyrrell. 1991 saw the patriotic Senna emotionally win his first Brazilian Grand Prix. His McLaren's manual gearbox was losing gears quickly and close to the end, he only had 6th gear left. This made the car much more difficult and physically demanding to drive, but he still eventually won holding off Williams driver Riccardo Patrese. His exhaustion was so high that had to be extricated from his car. 1992 saw Mansell dominate the weekend and the rest of the season. 1993 was a race of variables; it began to rain heavily early into the race and Prost, now driving a Williams, had a rare accident on the main straight and retired. Senna went on to win in a McLaren from Prost's teammate Damon Hill. 1994 saw Senna, now driving for Williams, spin his recalcitrant car going through Juncao late into the race. He was running in 2nd, trying to catch German Michael Schumacher, who went on to win. Senna would lose his life in an accident at the San Marino Grand Prix later in the year. 1995 was a very controversial race that initially had race winner Schumacher and Briton David Coulthard's cars excluded for apparently using illegal fuel during the race, but then reinstated. 1996 saw Damon Hill win his first of 8 races that season. 1997 saw an accident at the start that involved 4 cars, and Canadian Jacques Villeneuve went off the course at the first corner; the race was stopped and restarted, and Villeneuve jumped into the spare car and won the race. 1998 saw a controversy surrounding McLaren – Ferrari had protested about their braking system, and it was then banned from the Brazilian Grand Prix, although it had been approved 4 times by FIA technical delegate Charlie Whiting. It didn't matter much: Finnish McLaren driver Mika Häkkinen won the race anyway. 1999 saw local Rubens Barrichello lead for some time until the engine in his car failed, and Hakkinen won again.

The 2001 Grand Prix was notable for marking the explosive arrival of Juan Pablo Montoya onto the Formula One scene. The Colombian driver stunningly muscled his way past Michael Schumacher early on and led easily until an incident in which Arrows's Jos Verstappen ran into the back of his Williams-BMW and ended his race. Montoya did eventually laid to rest the ghost of this event by winning the 2004 race in his final Grand Prix for Williams before moving to McLaren, holding off his future teammate Kimi Räikkönen to take a hard-fought victory. The 2001 race is also notable for two brothers, Michael and Ralf Schumacher, sharing a row on the starting grid for the first time.

Particularly memorable recent Brazilian Grands Prix include the 2003 race, which saw a maiden Grand Prix victory, highly unexpectedly, and amidst chaotic and unusual circumstances, for Jordan's Giancarlo Fisichella. Heavy rain before and during the race produced problems with tyre selection which caught out many teams, which allowed the weak Minardi team to have a real chance for victory the only time ever, because they were the only team who prepared for the rainfall, but their drivers were also soon out. And treacherous track conditions caused multiple drivers to spin out of the race, including then-reigning World Champion Michael Schumacher, ending a remarkable run of race finishes dating back to the 2001 German Grand Prix. Amidst this, a number of drivers, including McLaren's Kimi Räikkönen and David Coulthard, led the race, and, when a heavy accident involving Renault's Fernando Alonso blocked the circuit and brought out the red flag, confusion reigned. Fisichella led the race at the time, having just overtaken Räikkönen; however, it was the Finn who was declared the race winner under the rule that stipulated that the race result in such circumstances was to be taken from the running order two laps prior to the race being stopped. This decision was overturned days later in the FIA Court of Appeal in Paris after new evidence came to light which proved that Fisichella had crossed the finish line in the lead for a second time before Alonso's accident, and therefore was the rightful winner. The 2004 event marked the first time since the race's admission to the Formula One Championship calendar that it was not one of the first three rounds of the championship season.

Fernando Alonso became the youngest ever Formula One World Champion at the 2005 Brazilian Grand Prix, his third place behind winner Juan Pablo Montoya and championship rival Kimi Räikkönen was enough to clinch the title with two races remaining.

For 2006, the Brazilian Grand Prix, as in 2004, was moved to the prestigious position of hosting the final round of the season, in what was Michael Schumacher's first farewell to Formula One, before his return for the 2010 season. Starting from 10th position on the grid, Schumacher did an astonishing job on his last race. He fell to 19th position on the ninth lap due to a flat tyre caused by a minor collision with Giancarlo Fisichella when the former was trying to overtake the latter. After pitting for a new tyre he returned to the race, just in front of leader Massa, so almost being lapped, then passing several drivers to take the chequered flag in fourth place, after a dazzling passing manoeuvre on Kimi Räikkönen. His performance was not enough to give 'Schumi' his eighth trophy, as Fernando Alonso, who needed only one point to become World Champion again, finished in second place. Brazilian Felipe Massa took pole position and led the race from start to finish to get the second victory of his career and to be greeted by celebrations from his Brazilian supporters.

In March 2008, the mayor of São Paulo announced that he had signed a new deal with Bernie Ecclestone to continue the holding of the Brazilian Grand Prix. This deal allowed the Brazilian race to be on the calendar until 2015. With this, Interlagos was set for major improvements in its pit and paddock facilities.[2]

In the final race of the 2008 season in Brazil, Lewis Hamilton became the youngest Formula One World Champion up to that point in Formula One history. After adopting a conservative strategy without risks for most of the race to secure at least 5th place, and the title, a late-race rain shower caused unexpected trouble. First, Hamilton was pushed down to 5th place by German Toyota driver Timo Glock who didn't enter the pits for intermediates like most other front runners. With just 3 laps to go, Sebastian Vettel then also overtook the Briton on the track which meant he would end up with equal points to Massa, but with one fewer victory. While everybody was focusing on the battle between these two (Vettel managed to stay in front in the end), against all expectations both were able to overtake Glock, who had lost all grip with his dry-weather tyres, in the very last corner before the finishing straight. This meant that, while the McLaren Drivers' Championship title rival Felipe Massa won the race in his Ferrari, Hamilton ultimately grabbed the fifth place he needed to become champion. Renault's Fernando Alonso, the previous youngest champion, was second ahead of Massa's teammate Kimi Räikkönen and Toro Rosso's Sebastian Vettel.

The 2009 race determined another Drivers' Champion, with Jenson Button in a Brawn finishing 5th to secure his only Drivers' Championship over Vettel, now driving for Red Bull, who finished 4th; Vettel's Australian teammate Mark Webber won the race ahead of Pole Robert Kubica. 2010 saw a wet qualifying and German Nico Hülkenberg drove an astonishing lap to put his non-competitive Williams on pole position. His countryman Vettel won the race ahead of Webber, and this race gave Red Bull the Constructors' Championship, and it set up a 4-way duel for the Drivers' title at the final round in Abu Dhabi. 2011 saw another Red Bull 1–2, but it was Webber this time who had won from Vettel, who had already won his second Drivers' title in Japan earlier that year. 2012 was another classic race, where Vettel this time had to do battle with Spanish Ferrari driver Fernando Alonso. After making a very poor start which dropped him to 22nd, he climbed up to 6th which was enough to see him win his 3rd consecutive Drivers' title. This race was also notable for being Michael Schumacher's last ever F1 race: the legendary German had made a comeback with Mercedes in 2010, but he did not win a single race – a huge surprise, considering he was the most successful F1 driver in history. 2013 saw Vettel win his 9th consecutive race that season which was a new record. 2014 saw the totally dominant Mercedes duo of Nico Rosberg and Lewis Hamilton finish 1–2 in the race. 2015 saw Rosberg win again; he had spent most of that season demoralized and at the mercy of his teammate Hamilton, who won his 3rd consecutive Drivers' Championship. 2016 saw continued Mercedes domination, but it was Hamilton who won with Rosberg second. But the Mercedes victory that day was overshadowed by heavy rain, multiple accidents and an astonishing drive from the Dutch teenager Max Verstappen, son of former F1 driver Jos Verstappen, who drove his Red Bull from 16th to 3rd in 15 laps after his team botched its tyre strategy.

Five Brazilian drivers have won the Brazilian Grand Prix, with Emerson Fittipaldi, Nelson Piquet, Ayrton Senna and Felipe Massa each winning twice, and Jose Carlos Pace winning once. The most wins ever is by the Frenchman Alain Prost, who has won the race 6 times (including 5 times at Jacarepaguá). Argentine driver Carlos Reutemann and Michael Schumacher have both won 4 times.

On 10 October 2013 it was announced that the contract for the Brazilian Grand Prix had been extended until 2022.[3]

The scheduled 2020 race was cancelled by Formula One Management in July that year due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, leaving promoters of the Interlagos race furious who say the losses they will make because of this and that it could mean the end of Formula One racing at the venue longer term.[4][5]

Rumours of a return to Rio de Janeiro

In spring 2019, Jair Bolsonaro, the President of Brazil, announced that the Brazilian Grand Prix would move back to Rio de Janeiro.[6] Because the Jacerapaquá circuit had been demolished to make way for the construction of facilities for the 2016 Summer Olympics, a new circuit is to be built in the Deodoro neighborhood of Rio de Janeiro.[6] However, this was denied by Formula One's commercial manager Sean Bratches.[7]

Official names

- 1979: Grande Premio do Brasil (no official sponsor)[8]

- 1981, 1988–1993, 1997–1998, 2002–2008, 2016: Grande Prêmio do Brasil [9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25]

- 1984, 1986: Grande Prêmio Brasil de Fórmula 1[26][27]

- 1985: GP do Brasil[28]

- 1987: GP do Brasil Fórmula 1[29]

- 1994–1996: Grande Prêmio do Brasil[30][31][32]

- 1999–2001: Grande Prêmio Marlboro do Brasil[33][34][35]

- 2009–2015: Grande Prêmio Petrobras do Brasil[36][37][38][39][40][41]

- 2017–2018: Grande Prêmio Heineken do Brasil[42][43][44]

- 2019: Heineken Grande Prêmio do Brasil[45][46]

Winners

Repeat winners (drivers)

Drivers in bold are competing in the Formula One championship in the current season.

A pink background indicates an event which was not part of the Formula One World Championship.

| Wins | Driver | Years won |

|---|---|---|

| 6 | 1982, 1984, 1985, 1987, 1988, 1990 | |

| 4 | 1972, 1977, 1978, 1981 | |

| 1994, 1995, 2000, 2002 | ||

| 3 | 2010, 2013, 2017 | |

| 2 | 1973, 1974 | |

| 1983, 1986 | ||

| 1989, 1992 | ||

| 1991, 1993 | ||

| 1998, 1999 | ||

| 2004, 2005 | ||

| 2006, 2008 | ||

| 2009, 2011 | ||

| 2014, 2015 | ||

| 2016, 2018 |

Repeat winners (constructors)

Teams in bold are competing in the Formula One championship in the current season.

A pink background indicates an event which was not part of the Formula One World Championship.

| Wins | Constructor | Years won |

|---|---|---|

| 12 | 1974, 1984, 1985, 1987, 1988, 1991, 1993, 1998, 1999, 2001, 2005, 2012 | |

| 11 | 1976, 1977, 1978, 1989, 1990, 2000, 2002, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2017 | |

| 6 | 1981, 1986, 1992, 1996, 1997, 2004 | |

| 5 | 2009, 2010, 2011, 2013, 2019 | |

| 4 | 2014, 2015, 2016, 2018 | |

| 3 | 1972, 1975, 1983 | |

| 2 | 1980, 1982 | |

| 1994, 1995 |

Repeat winners (engine manufacturers)

Manufacturers in bold are competing in the Formula One championship in the current season.

A pink background indicates an event which was not part of the Formula One World Championship.

| Wins | Manufacturer | Years won |

|---|---|---|

| 11 | 1976, 1977, 1978, 1989, 1990, 2000, 2002, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2017 | |

| 10 | 1980, 1982, 1992, 1995, 1996, 1997, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2013 | |

| 9 | 1972, 1973, 1974, 1975, 1979, 1981, 1993, 1994, 2003 | |

| 8 | 1998, 1999, 2005, 2012, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2018 | |

| 4 | 1986, 1988, 1991, 2019 | |

| 3 | 1984, 1985, 1987 | |

| 2 | 1983, 2004 |

* Built by ![]()

** Between 1998-2005 built by ![]()

*** Built by ![]()

By year

A pink background indicates an event which was not part of the Formula One World Championship.

References

- "Brazilian GP, 1978 Race Report – GP Encyclopedia – F1 History on Grandprix.com". Grandprix.com. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- Autosport magazine, 27 March 2008 p.11

- "Brazil signs contract extension through 2022". F1 Times. 10 October 2013. Archived from the original on 27 February 2014. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- Benson, Andrew. "US, Mexican & Brazilian races cancelled". BBC Sport. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- "Brazilian GP promoter hits out at F1 over 2020 race cancellation". www.motorsport.com. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- Noble, Jon; Faldon, Gustavo (8 May 2019). "Brazilian president reveals grand prix will move to Rio for 2020". Autosport. Motorsport Network. Archived from the original on 8 May 2019.

- "F1 boss denies Brazilian GP is moving". Speedcafe. 13 May 2019. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- "1979 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1981 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1988 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1989 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1990 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1991 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1992 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1993 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1997 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1998 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2002 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2003 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2004 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2005 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2006 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2007 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2008 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2016 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1984 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1986 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1985 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1987 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1994 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1995 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1996 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1999 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2000 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2001 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2009 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2010 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2011 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2012 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2014 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2015 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2017 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "Formula 1 Grande Prêmio Heineken do Brasil 2017". Formula1.com. Formula One World Championship Ltd. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- "2018 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "Formula 1 Heineken Grande Prêmio do Brasil 2019". Formula1.com. Formula One World Championship Ltd. Retrieved 22 April 2019.

- "Brazilian Grand Prix 2020 – F1 Race". Formula 1® – The Official F1® Website. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Brazilian Grand Prix. |