National Museum of Brazil

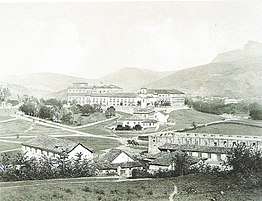

The National Museum of Brazil (Portuguese: Museu Nacional) is Brazil's oldest scientific institution.[3][4] It is located in the city of Rio de Janeiro, where it is installed in the Paço de São Cristóvão (Saint Christopher's Palace), which is inside the Quinta da Boa Vista. The main building was originally the residence of the Portuguese Royal Family between 1808 and 1821 and was later used to house the Brazilian Imperial Family between 1822 and 1889. After the monarchy was deposed, it hosted the Republican Constituent Assembly from 1889 to 1891 before being assigned to the use of the museum in 1892. The building was listed as Brazilian National Heritage in 1938[5] and was largely destroyed by a fire in 2018.

Museu Nacional | |

| |

| |

| Established | 6 June 1818 |

|---|---|

| Location | Quinta da Boa Vista in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil |

| Coordinates | 22°54′21″S 43°13′34″W |

| Type | Natural history, ethnology and archaeology |

| Collection size | approx. 20 million objects (before 2018 fire),[1] 1.5 million objects placed in other buildings (after 2 September 2018 fire) |

| Visitors | approx. 150,000 (2017)[2] |

| Founder | King João VI of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves |

| Director | Alexander Wilhelm Armin Kellner |

| Owner | Federal University of Rio de Janeiro |

| Website | museunacional |

| Ruin | |

Founded by King João VI of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves on 6 June 1818, under the name of "Royal Museum", the institution was initially housed at the Campo de Santana park, where it exhibited the collections incorporated from the former House of Natural History, popularly known as Casa dos Pássaros ("House of the Birds"), created in 1784 by the Viceroy of Brazil, Luís de Vasconcelos e Sousa, 4th Count of Figueiró, as well as collections of mineralogy and zoology. The museum foundation was intended to address the interests of promoting the socioeconomic development of the country by the diffusion of education, culture, and science. In the 19th century, the institution was already established as the most important South American museum of its type. In 1946, it was incorporated into the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro.[6][5][7]

The National Museum held a vast collection with more than 20 million objects, one of the largest collections of natural history and anthropological artifacts in the world, encompassing some of the most important material records regarding natural science and anthropology in Brazil, as well as numerous items that came from other regions of the world and were produced by several cultures and ancient civilizations. Built-up over more than two centuries through expeditions, excavations, acquisitions, donations and exchanges, the collection was subdivided into seven main nuclei: geology, paleontology, botany, zoology, biological anthropology, archaeology, and ethnology. The collection was the principal basis for the research conducted by the academic departments of the museum – which are responsible for carrying out activities in all the regions of the Brazilian territory and several places of the world, including the Antarctic continent. The museum holds one of the largest scientific libraries of Brazil, with over 470,000 volumes and 2,400 rare works.[5]

In the area of education, the museum offers specializations, extension and post-graduation courses in several fields of the knowledge, in addition to hosting temporary and permanent exhibitions and educational activities open to the general public.[5] The museum manages the Horto Botânico (Botanical Garden), adjacent to the Paço de São Cristóvão, as well as an advanced campus in the city of Santa Teresa, in Espírito Santo – the Santa Lúcia Biological Station, jointly managed with the Museum of Biology Prof. Mello Leitão. A third site, located in the city of Saquarema, is used as a support and logistics center for field activities. Finally, the museum is also dedicated to editorial production, outstanding in that field the Archivos do Museu Nacional, the oldest scientific journal of Brazil,[8] continuously published since 1876.[6][9]

The palace, which housed a large part of the collection, was destroyed in a fire on the night of 2 September 2018.[10][11][12] The building had been called a "firetrap" by critics, who argued the fire was predictable and could have been prevented.[13] The fire began in the air-conditioning system of the auditorium on the ground floor. One of the three devices did not have external grounding, there was no individual circuit breaker for each of them, and a wire was without insulation in contact with metal.[14] In the wake of the fire, the ruined edifice is being treated as an archaeological site and undergoing reconstruction efforts, with a metallic roof covering a 5,000 m² area including debris.[15]

In 2019, more than 30,000 pieces of the Imperial Family's past were found during archaeological works on Rio de Janeiro Zoological Garden nearby, part of Quinta da Boa Vista. Among the finds are many items such as fragments of crockery, cups, plates, cutlery, horseshoes and even buttons and brooches with imperial coat of arms from military clothing. Those items were given to the museum.[16] After being destroyed by fire, the National Museum has received donations to the amount of R$ 1.1 million in seven months towards rebuilding efforts.[17] The financial help is expected more from international influences than from the local Brazilian population.

History

The National Museum was officially established by King João VI of Portugal, Brazil, and the Algarves (1769–1826) in 1818 with the name Royal Museum, in an initiative to stimulate scientific research in the Kingdom of Brazil, then a constituent part of the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil, and the Algarves. Initially, the museum housed plant and animal specimens, especially birds, which caused it to be known by locals n as the "House of the Birds".

After the marriage of King João VI's eldest son and Brazil's first Emperor, Dom Pedro I (1798–1834), to H.I. & R.H. Archduchess Maria Leopoldina of Austria (1797–1826), the Museum started to attract some of the greatest European naturalists of the 19th century, such as Maximilian zu Wied-Neuwied (1782–1867), Johann Baptist von Spix (1781–1826), and Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius (1794–1868). Other European researchers who explored the country, such as Augustin Saint-Hilaire (1799–1853) and the Baron von Langsdorff (1774–1852), contributed to the collections of the Royal Museum.[18]

By the end of the 19th century, reflecting the personal preferences of His Imperial Majesty Emperor Pedro II (1825–1891), the National Museum started to invest in the areas of the anthropology, paleontology and archaeology. The Emperor himself, who was an avid amateur scientist and enthusiastic supporter of all branches of science, contributed with several of the collections of the art of Ancient Egypt, botanical fossils, etc., which he acquired during many of his trips abroad. In this way, the National Museum was modernized and became the most important museum of natural history and human sciences of South America. Edmund Roberts visited the museum in 1832, noting that the museum only had three open rooms at that time, and that the closed rooms were "sadly plundered of its contents by Don Pedro."[19]

D. Pedro II was well aware of the shortage of true scientists and naturalists in Brazil. He fixed this problem by inviting foreign scientists to come to work at the Museum. The first to come was Ludwig Riedel (1761–1861), a German botanist who had participated in Baron von Langsdorff's famed expedition to Mato Grosso from 1826 to 1828. Other scientists to come were German chemist Theodor Peckolt and American geologist and paleontologist Charles Frederick Hartt (1840–1878). In the following years, the museum gradually became known so it continued to attract several foreign scientists who wished to achieve scientific stature with their work in Brazil, such as Fritz Müller (1821–1897), Hermann von Ihering (1850–1930), Carl August Wilhelm Schwacke (1848–1894), Orville Adalbert Derby (1851–1915), Émil August Goeldi (1859–1917), Louis Couty (1854–1884) and others; all of them were fired by museum director Ladislau Netto when the Emperor was deposed.

The Emperor was a very popular figure when he was deposed by a military coup in 1889, so the republicans tried to erase the symbols of the Empire. One of these symbols, the Paço de São Cristóvão, the official residence of the emperors in the Quinta da Boa Vista, became vacant; therefore, in 1892, the National Museum, with all its collections, valuables and researchers, was transferred to this palace, where it stays until today.

In 1946, the museum's management was passed to the University of Brazil, currently the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. The researchers and their offices and laboratories occupy a good part of the palace and other buildings erected at Botanical Gardens (Horto Florestal), in the Quinta da Boa Vista park – one of the largest scientific libraries of Rio. The National Museum offers graduate courses in the following areas: anthropology, sociology, botany, geology, paleontology, and zoology.

Former collections

The museum sheltered one of the largest exhibits of the Americas, prior to the fire, consisting of animals, insects, minerals, aboriginal collections of utensils, Egyptian mummies and South American archaeological artifacts, meteorites, fossils and many other findings.

One of the meteorites that was on display is the Bendegó meteorite, which weighs over 5,000 kilograms (11,000 lb) and was discovered in 1784.[21]

Archaeology

The collection of archaeology of the National Museum comprised more than 100,000 objects, covering distinct several civilizations that lived in the Americas, Europe, Africa, and the Middle East, since the Paleolithic Age until the 19th century. The collection is subdivided into four main segments: Ancient Egypt, Mediterranean cultures, Pre-Columbian archaeology, and Pre-Columbian Brazil – last nucleus, systematically gathered since 1867, is the largest segment of the archaeological collection, as well as the most important collection of its typology in the world, covering the history of Pre-Cabraline Brazil in a very comprehensive manner and sheltering some of the most important material records related to Brazilian archaeology. It was, therefore, a collection of considerable scientific value, and object of several works of basic research, theses, dissertations, and monographs.[22][23]

Ancient Egypt

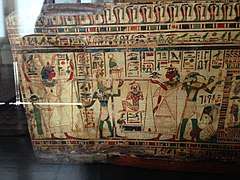

With more than 700 items, the collection of Egyptian archaeology of the National Museum was one of the largest of Latin America and one of the oldest in the Americas. Most part of the objects entered the museum collection in 1826, when the tradesman Nicolau Fiengo brought from Marseille an assemblage of Egyptian antiquities that belonged to the famous Italian explorer Giovanni Battista Belzoni, who had been in charge of excavating the Theban Necropolis (modern-day Luxor) and the Temple of Karnak.[24]

This collection had Argentina as the initial destination, and had probably been ordered by the president of that country, Bernardino Rivadavia, creator of the University of Buenos Aires and a noted enthusiast of museums. However, a naval blockade at the La Plata River would impede Fiengo from completing his journey, forcing him to return from Montevideo to Rio de Janeiro, where the pieces were offered at an auction. Emperor Pedro I bought the entire collection for five million réis, and subsequently donated it to the National Museum. It has been suggested that the action of Pedro I would have been influenced by José Bonifácio de Andrada, a relevant early member of Freemasonry in Brazil, perhaps driven by the interest that the organization had for the Egyptian iconography.[25][26] [27]

The collection started by Pedro I would be expanded by his son, emperor Pedro II, an amateur Egyptologist and notable collector of archaeological and ethnographic artifacts. One of the most important additions to the Egyptian collection of the National Museum made by Pedro II is the polychromed wood sarcophagus of the singer of Amun, Sha-Amun-en-su, from the Late Period, offered to the emperor as a gift during his second trip to Egypt, in 1876, by the Khedive Ismail Pasha. The sarcophagus is distinguished for its rarity, since it is one of few examples that have never been opened, still preserving the mummy of the singer in its interior.[24] The collection would be enriched through other acquisitions and donations, becoming, at the beginning of the 20th-century, sufficiently relevant to draw the attention of international researchers and Egyptologists, such as Alberto Childe, who served as conservator of the Department of Archaeology of the museum between 1912 and 1938 and was also responsible for publishing the Guide of the Collections of Classical Archaeology of the National Museum, in 1919.[25][26][27]

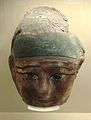

Besides the aforementioned coffin of Sha-Amun-en-su, the museum possesses other three sarcophagi, from the Third Intermediate Period and the Late Era, belonging to three priests of Amun: Hori, Pestjef, and Harsiese. The museum also conserves six human mummies (four adults and two children), as well as a number of mummies and sarcophagi of animals (cats, ibises, fishes, and crocodiles). Among the human examples, the highlight is a mummy of a woman from the Roman Period, which is considered extremely rare for the preparatory technique used, of which there are only eight similar examples worldwide. Called "princess of the Sun" or "princess Kherima", the mummy has her members and fingers of the hands and feet individually swaddled and is richly adorned, with painted strips.[27] "Princess Kherima" is one of the most popular items of the National Museum collection, being even related to accounts of parapsychological experiences and collective trances, that supposedly occurred in the 1960s. "Kherima" also inspired the romance The Secret of the Mummy by Everton Ralph, member of the Rosicrucian society.[25][28][29]

The collection of votive and funerary steles is composed of dozens of pieces dated, in their majority, from the Intermediate Period and the Late Era. The steles of Raia and Haunefer, which are graved with titles of Semitic origins present in the Bible and in the tablets of Mari, stand out, as well as an unfinished stele, attributed to the emperor Tiberius, of the Roman Period. The museum also had a vast collection of shabtis, i.e. statuettes representing funerary servers, including a group of pieces that belonged to pharaoh Seti I, excavated from his tomb at the Valley of the Kings. The rare artifacts included a limestone statue of a young woman, dated of the New Kingdom, carrying a conic ointment vessel on the top of her head – an iconography that is almost exclusively found among paintings and reliefs. The collection also includes fragments of reliefs, masks, statues of deities in bronze, stone and wood (such as representations of Ptah-Sokar-Osiris), canopic jars, alabaster bowls, funerary cones, jewels, and amulets.[25][27][30]

Stele of Raia. New Kingdom, XIX Dynasty, c. 1300–1200 BC

Stele of Raia. New Kingdom, XIX Dynasty, c. 1300–1200 BC_01.jpg)

Bronze statuette of Amun.

Bronze statuette of Amun. Golden mask. Ptolemaic Kingdom, c. 304 BC.

Golden mask. Ptolemaic Kingdom, c. 304 BC._01.jpg) Harsiese Sarcophagus interior

Harsiese Sarcophagus interior Cat Sacophagus

Cat Sacophagus

Lion figure

Lion figure

Mediterranean cultures

The collection of classical archaeology of the National Museum added up to around 750 pieces and consists mostly of Greek, Roman, Etruscan, and Italiote objects, being the largest collection of its kind in Latin America. Most of the pieces previously belonged to the Greco-Roman collection of empress Teresa Cristina, who had been interested in archaeology since her youth. When the empress disembarked in Rio de Janeiro in 1843, right after her proxy wedding to emperor Pedro II, she brought an assemblage of antiquities found during the excavations of Herculaneum and Pompeii, the Ancient Roman cities destroyed by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD. Part of this collection had also belonged to Carolina Murat, sister of Napoleon Bonaparte and queen consort of the king of Naples, Joachim Murat.[31][32][33]

In turn, Ferdinand II of the Two Sicilies, brother of empress Teresa Cristina, had ordered the excavations of Herculaneum and Pompeii, initiated in the 18th century, be resumed. The recovered pieces were sent to the Royal Bourbon Museum of Naples. Aiming to increase the number of classical artifacts in Brazil with a view to the future creation of a museum of Greco-Roman archaeology in the country, the empress established formal exchanges with the Kingdom of Naples. She requested the shipment of Greco-Roman objects to Rio de Janeiro, while sending artifacts of indigenous origins to Italy. The empress also personally financed excavations in Veios, an Etruscan archeological site located fifteen kilometers north of Rome, thus enabling a large part of the objects found there to be brought to Brazil. A greater part of those had been gathered between 1853 and 1859, but Teresa Cristina continued to enrich the collection until the fall of the Brazilian empire in 1889, when the Republic was proclaimed and the empress left the country with all the royal family.[31][32]

Among the highlights of the collection were a set of four frescos from Pompeii, made around the 1st century AD. Two of those are decorated with marine motifs, respectively depicting a sea dragon and a seahorse as the central figure surrounded by dolphins, and had adorned the lower walls of the room of the devotees at the Temple of Isis. The other two frescos are decorated with representations of plants, birds, and landscapes, stylistically close to the paintings of Herculaneum and Stabiae. The museum also housed a large number of objects from Pompeii portraying the daily life of Ancient Roman citizens: fibulae, jewels, mirrors, and other pieces of the Roman female toilette, glass and bronze vessels, phallic amulets, oil lamps molded in terracotta, etc.[28][33][34]

The collection of Mediterranean pottery comprised more than dozens of objects and is noted for the diversity of origins, shapes, decorations and utilitarian purposes. Several of the most important styles and schools of classical antiquity are represented, from the Corinthian geometric style of the 7th century BC to the Roman terracotta amphoras of the Early Christian era. The museum houses examples of kraters, oenochoai, kantharos, chalices, kyathos, cups, hydriai, lekythoi, askoi, and lekanides. The groups of Etruscan Bucchero pottery (7th–4th centuries BC), Greek black-figure vases (7th–5th centuries BC), Gnathian vessels (4th century BC), and the vast set of Italian red-figure vases, with ceramics from Apulia, Campania, Lucania and Magna Graecia, which also stand out.[28]

The collection of sculptures comprised a large number of Tanagra figurines, small terracotta sculptures of Greek origin that were widely appreciated in the Ancient world, as well as a group of Etruscan bronze statuettes representing warriors and female figures. The collection of military artifacts included entire pieces or fragments of helmets, maces, scabbards, bronze blades, brooches and phalleras.[28]

_01.jpg)

Corinthian oinochoe with lid, c. 600–575 BC

Corinthian oinochoe with lid, c. 600–575 BC Campanian Red-figure chalice krater, late 4th century BC

Campanian Red-figure chalice krater, late 4th century BC

_-_pequenas_%C3%A2nforas.jpg)

Pre-Columbian archaeology

The National Museum housed an important group of about 1,800 artifacts produced by the Indigenous peoples of the Americas during the Pre-Columbian era, as well as Andean mummies. Gathered throughout the 19th century, the collection was based on holdings of the Brazilian royal family, with several objects coming from the private collection of Emperor Pedro II. It was later enlarged through acquisitions, donations, exchanges, and excavations. By the end of the 19th-century, the collection already had considerable prestige, being cited, on the occasion of opening the 1889 Anthropological Exposition, as one of the largest collections of South American archaeology.[28][35][36]

The collection comprised mostly objects related to the textile manufacturing, featherwork, ceramic production, and stonecraft of the Andean cultures (groups of Peru, Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina) and, to a lesser extent, of the Amazonian natives (including a rare assemblage of artifacts from the area of present-day Venezuela) and Mesoamerican cultures (mainly from present-day Mexico and Nicaragua). Several aspects of the daily routine, social organization, religiosity, and imagery of the Pre-Columbian civilizations are addressed in the collection, which has items from common daily use (clothing, body ornaments, weapons) to more refined artifacts, imbued with notable artistic sense (measurement and musical instruments, ritual objects, figurative ceramic sculptures and vessels distinguished for their aesthetic features).[35][28] Other aspects of Pre-Columbian life, such as the dynamics of trade, ideological diffusion, and cultural influences among the groups, are also represented in the collection. Items are evaluated in terms of the similarity of decorative patterns and artistic techniques, as well as in the subjects portrayed. Common to nearly all distinct groups are such subjects as plants, nocturnal animals (bats, serpents, owls), and fantastic creatures associated to natural elements and phenomena.[37][28][38]

The best represented groups, in the context of Andean cultures, include:

- Nazca culture, which flourished on the southern coast of Peru between the 1st century BC and 800 AD. The National Museum has a large set of fragments of Nazca textiles depicting animals (mainly llamas), fantastic beings, plants, and geometric patterns;[37]

- Moche civilization, which flourished on the northern coast of Peru between the early Christian era and 8th century AD, responsible for building large monuments, temples, pyramids, and ceremonial complexes, represented in the collection by a group of figurative pottery of high artistic and technical quality (zoomorphic, anthropomorphic, and globular vessels) and examples of goldsmithery;[39][40]

- Wari culture, which inhabited the south-central Andes since the 5th century AD, represented by anthropomorphic ceramic vessels and textile fragments;[40]

- Lambayeque culture, which arose in the homonymous region of Peru during the 8th century AD, exemplified in the collection through textiles, pottery and metalwork;[41]

- Chimú culture, which flourished on the Valley of the Moche River since the 10th century AD, represented by a group of zoomorphic and anthropomorphic pottery (characteristically dark, obtained through the technique of reducing burning, and inspired by stylistic elements of the Moche and Wari cultures), as well as textiles decorated with varying motifs;[42][43]

- Chancay culture, which developed between the Intermediate and Late periods (from about 1000 to 1470 AD), on the valleys of the rivers Chancay and Chillon, presented in the collection by a set of anthropomorphic pottery (characteristically dark, decorated with light-colored engobe and brown painting) and sophisticated textiles depicting animals and vegetables – namely a large mantle, with three meters of length;[28][44]

- Inca civilization, which flourished around the 13th century AD and became the largest empire of the Pre-Columbian Americas in the following century. The National Museum possesses a set of figurative pottery and vessels decorated with geometric patterns ("Incan aryballos"), miniature figures of human beings and llamas, made with alloys of gold, silver, and copper, miniatures of Inca ceremonial clothing, featherwork, quipus, mantles, tunics, and several other examples of textiles.[45][46]

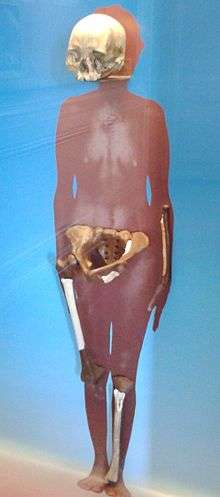

The collection of Andean mummies of the National Museum allows a glimpse at the funerary practices of the cultures of the region. The mummies of the collection were preserved either naturally (as a result of the favorable geo-climatic conditions of the Andean Mountains) or artificially, in the context of religious and ritualistic practices. Originating from Chiu Chiu, at the Atacama Desert, northern Chile, there is a mummy of a man with an estimated age of 3,400 to 4,700 years, preserved in a seated position, with the head resting on the knees and covered by a wool cap. This was the position which the Atacaman cultures used to sleep, due to the cold climate of the desert. It was also the position in which they were buried, together with their belongings.[47] A second mummy in the collection – an Aymara man, found in the surroundings of Lake Titicaca, between Peru and Bolivia – is preserved in the same position, but involved in a funerary bundle.[48] The collection of mummies also include a boy, donated by the Chilean government, and, illustrating the techniques of artificial mummification of Pre-Columbian cultures, an example of a shrunken head, coming from the Jivaroan peoples of equatorial Amazon, of ritualistic purposes.[38][49]

Brazilian archaeology

The collection of Brazilian archaeology of the National Museum brought together a vast set of artifacts produced by the cultures that flourished in the Brazilian territory during the pre-colonial era, with more than 90,000 objects. It was considered the largest collection in its typology worldwide. Gradually assembled since the early 19th century, the collection started being systematically gathered since 1867 and has been continually expanded until the present day, through excavations, acquisitions and donations, also serving as basis for a large number of research projects conducted by the academics of the museum, the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, and other institutions. It was composed of objects coming from all regions of Brazil, establishing a timeline spanning more than 10,000 years.[38][23][22]

From the oldest inhabitants of the Brazilian territory (horticulturists and hunter-gatherer groups), the museum preserved several artifacts made of stone (flint, quartz and other minerals) and bones, such as projectile points used for hunting, axe blades of polished stone and other tools used for carving, scraping, cleaving, triturating, and piercing, in addition to artifacts of ceremonial use and adornments. Although objects made of wood, fiber, and resin were also produced, the majority of them didn't stand the test of time and are almost absent in the collection, except for some individual pieces – namely a woven straw basket covered by resin, only partially preserved, found in the southern coast of Brazil.[38][50][37][51]

In the segment regarding the Sambaqui people, i.e. the fishing and gathering communities which lived in the south-central coast of Brazil between 8,000 years before present and the early Christian era, the National Museum holds a large number of vestiges originating from deposits constituted of agglomerated lime and organic material – the so-called Sambaquis, or middens. Two fragments of Sambaquis are preserved in the collection, in addition to a group of human skeletal remains found in these archaeological sites, as well as several cultural testimonies of the Sambaqui people, encompassing utilitarian objects used in routine tasks (vessels, bowls, pestles and mortars carved in stone), ceremonies and rituals (such as votive statuettes). Among the highlights of the Sambaqui collection, there is a large set of zoolites (stone sculptures of votive use, with representation of animals, such as fish and birds, and human figures).[38][37]

The collection included several examples of funerary urns, rattles, dishes, bowls, clothing, dresses, idols, and amulets, with emphasis being placed on ceramic objects, produced by numerous cultures of precolonial Brazil.[38] Best represented groups in the collection include:

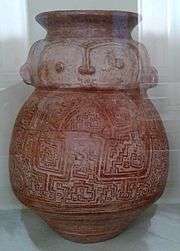

- Marajoara culture, which flourished on Marajó island, at the mouth of the Amazon River, between the 5th and the 15th centuries, considered the group that reached the highest level of social complexity in precolonial Brazil. The museum has a vast assemblage of Marajoara pottery, notable for their heightened artistic and aesthetic sense, as well as for the variety of shapes and refined decoration – mostly works of figurative nature (representations of humans and animals), combined with rich geometric patterns (compositions imbued with symmetry, rhythmic repetitions, paired elements, binary oppositions, etc.) and with a predominant usage of the excision technique. Major part of the ceramic pieces are of ceremonial nature, used in funerary contexts, rites of passage, etc. Among the highlights, it's possible to mention the anthropomorphic statuettes (particularly the phallus-shaped female figurines, uniting the male and female principles, a recurring theme of the Marajoara art), large-scale funerary urns, anthropomorphic vases with geometric decoration, ritual thongs, zoomorphic, anthropomorphic and hybrid vessels, etc.[52]

- Santarém culture (or Tapajós culture), which inhabited the region of the Tapajós River in the state of Pará, between the 5th and the 15th centuries, known for their ceramic work of peculiar style and high technical quality, produced with the techniques of modeling, incision, dotted lines, and appliqué, imbued with aesthetic features that suggest the influence of the Mesoamerican civilizations. Among the highlights of the collection were the anthropomorphic statuettes of naturalist style (characterised by the closed eyes, shaped like coffee beans), the anthropomorphic and zoomorphic vessels, vases for ceremonial use and, above all, the so-called "caryatid vases" – complex ceramic vessels, endowed with bottlenecks, reliefs and pedestals decorated with anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figurines and fantastic beings. The museum also possesses several examples of Muiraquitãs, i.e. small statuettes carved in green gems, shaped like animals (mainly frogs) used as adornments or amulets.[52]

- Konduri culture, which reached their apex in the 7th century and met their decline in the 15th century, and inhabited the region between the Trombetas and Nhamundá rivers, in Pará. Although this culture kept an intense contact with the Santarém culture, their artistic production developed unique features. The Konduri collection is primarily composed of pottery, noted for the techniques of decoration such as incision and dotted lines, the lively polichromy, and the reliefs with anthropomorphic and zoomorphic motifs.[53]

- Trombetas River culture, which inhabited the lower Amazon, in the state of Pará, near the region of Santarém. This culture, still largely unknown, was responsible for producing rare artifacts sculpted in polished stone and objects imbued with stylistic elements common to the Mesoamerican cultures. The museum collection preserves lithic artifacts of ceremonial use, as well as anthropomorphic and zoomorphic statuettes (zoolites representing fish and jaguars).[54]

- Miracanguera culture, which flourished on the left bank of the Amazon river, in the region between Itacoatiara and Manaus, between the 9th and the 15th centuries. The museum preserved several examples of ceremonial pottery, mainly anthropomorphic funerary urns characterized by the presence of bulges, necks, and lids, used to store the ashes of the deceased, and other vessels related to funerary rituals. The Miracanguera pottery is distinguished for the presence of tabatinga layers (clay mixed with organic materials) and the eventual painted decoration of geometric motifs. The plastic composition frequently outlines specific details, such as human figures in a seated position, with the legs represented.[55]

- Maracá culture, which lived in the region of Amapá between the 15th and the 18th centuries, represented in the collection by a group of typical funerary urns depicting male and female figurines in hierarchic position, with head-shaped lids, as well as zoomorphic funerary urns depicting quadrupedal animals, originating from indigenous cemeteries located in the outskirts of the Maracá River. The Maracá pottery was frequently adorned with geometric patterns and polychromed with white, yellow, red, and black pigments. Ornaments in the members and the head of the figures expressed the social identity of the deceased.[56]

- Tupi-Guaraní culture, which inhabited the Brazilian coast when the Portuguese arrived in the 16th century – subdivided into the group of the Tupinambá people (in the North, Northeast, and Southeast regions of Brazil) and the group of the Guaraní people (in the South region of Brazil and parts of Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay). The collection is predominantly composed of ceramics and lithic artifacts of daily use (such as pans, bowls, jars, and dishes) or ritual nature (mainly funerary urns). The Tupi-Guaraní pottery is characterized by its distinct polychromy (with predominance of red, black, and white pigments) and drawings of geometric and sinuous patterns.[57]

The National Museum held the oldest known examples of indigenous mummies found in the Brazilian territory. The collection consisted of the body of an adult woman of approximately 25 years of age, and two children, one located at her feet, with an estimated age of twelve months, involved in a bundle, and a new-born, also covered by a mantle, positioned behind the head of the woman. This mummified set is composed of individuals that probably belonged to the group of the Botocudos (or Aimoré) people, of the Macro-Jê branch. They were found at the Caverna da Babilônia, a cavern located in the city of Rio Novo, interior of the state of Minas Gerais, in a farm that belonged to Maria José de Santana, who donated the mummies to emperor Pedro II. As an act of gratitude for this favor, Pedro II awarded Maria José with the title of Baroness of Santana.[58]

Gallery

Recreation of dinosaur heads

Recreation of dinosaur heads Pompeii fresco

Pompeii fresco Pompeii fresco

Pompeii fresco Historic artwork of the interior

Historic artwork of the interior

Ceiling artwork

Ceiling artwork

Artwork of an Egyptian sarcophagus

Artwork of an Egyptian sarcophagus Butterflies on display

Butterflies on display The throne room, on display in preserved rooms in the front wings of the museum

The throne room, on display in preserved rooms in the front wings of the museum Part of the preserved throne room

Part of the preserved throne room Pre-Columbian artifacts

Pre-Columbian artifacts Pre-Columbian jars and ceramics

Pre-Columbian jars and ceramics

Ancient Greek vases

Ancient Greek vases Paleontological tools

Paleontological tools

Financial difficulties

From 2014 the museum faced budget cuts that dropped its maintenance to less than R$ 520,000 annually. The budget was so low, there was US$ 0.01 to spend on each of the artifacts.[59] The building fell into disrepair, evidenced by peeling wall material, exposed electrical wiring, and termite problem.[60][59] By June 2018, the museum's 200th anniversary, it had reached a state of near-complete abandonment.[61] There was an offer from the World Bank to purchase the museum for US$80 m, which was turned down because the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro would have to give up ownership.[59]

According to the dean of UFRJ Denise Pires de Carvalho, the university does not have the money to pay bills of light delayed since January 2019, of water since 2 years, of security and cleaning services. She also said that although they do not have any more money available, she would seek the release of 20% of the R$43 million released by the parliamentary bench in Rio de Janeiro to continue the reconstruction works of the National Museum. It aims to reopen at least one wing of the palace in 2022, the year of independence bicentennial.[62]

2018 fire

The National Museum building burning behind the statue of Emperor Pedro II | |

| Native name | Incêndio no Museu Nacional |

|---|---|

| Date | 2 September 2018 (1 year) |

| Time | 23:30 UTC |

| Duration | 6 hours |

| Location | Rio de Janeiro, RJ, |

| Type | Conflagration |

| Cause | Overheating of air conditioning caused by short circuit.[63][64] |

| Outcome | Approximately 18.5 million (92.5 %) of the museum's 20 million items were destroyed.[65] |

| Deaths | 0 |

| Non-fatal injuries | 1, a firefighter suffered burns to his fingers trying to save the skull of Luzia.[66] |

| Property damage | Paço de São Cristóvão |

The building was heavily damaged by a large fire which began about 19:30 local time (23:30 UTC) on 2 September 2018.[10][12][67]

Although some items were saved, it is believed that 92.5% of its archive of 20 million items were destroyed in the fire, though circa 1.5 million items are stored in a separate building, which were not damaged.[11]

First responders fighting the fire were hindered by a lack of water. Rio's fire chief claimed that two nearby fire hydrants had insufficient water, leaving firefighters to resort to pumping water from a nearby lake. According to a CEDAE (Rio de Janeiro's Water and Sewerage State Company) employee, although the hydrants did have water, the water pressure was very low, due to the fact that the building is on top of a hill.[68][69] Brazil President Michel Temer claimed the loss due to the fire to be "incalculable."[67]

Background

Museum Deputy Director Luiz Fernando Dias Daniel pointed to neglect by successive governments as a cause of the fire,[70][71] saying that curators "fought with different governments to get adequate resources to preserve what is now completely destroyed" and that he felt "total dismay and immense anger."[72] The museum lacked a fire sprinkler system, although there were smoke detectors and a few fire extinguishers.[73][74] The museum did not receive the R$520,000 per year necessary for its maintenance since 2014, and it closed temporarily in 2015 when cleaning and security staff could no longer be paid. Repairs to a popular exhibit hall had to be crowd-funded, and the museum's maintenance budget had been cut by 90 per cent by 2018.[75] There were visible signs of decay before the fire, such as peeling walls and exposed wiring.[76] The museum celebrated its 200th anniversary in June 2018 in a situation of partial abandonment. No state ministers attended the occasion.[72][77][78]

Fire

A large fire broke out shortly after the museum closed on 2 September 2018, reaching all three floors of the building.[79][80][81] Firefighters were called at 19:30 local time (22:30 UTC)[82] and arrived quickly at the scene.[78] However, the fire chief reported that the two fire hydrants closest to the museum had no water, and trucks had to be sent to a nearby lake.[83] According to the spokesman for the fire department, the fire crews went inside the burning building to rescue artifacts, despite there being no people inside, and they were able to remove items with the help of museum staff.[84][85]

The fire was out of control by 21:00 (00:00 UTC 3 September), with great flames and occasional explosions,[86] being fought by firefighters from four sectors.[87] Dozens of people went to Quinta da Boa Vista to see the fire.[78] A specialized team of firefighters entered the building at 21:15 to block areas still not hit by the flames and to evaluate the extent of the damage.[88] However, by 21:30, the whole building had been engulfed by the fire, including exhibitions of Imperial rooms that were in the two areas at the front of the main building. The four security guards who were on duty at the museum managed to escape; first reports stated that there were no casualties, although a firefighter suffered burns to the fingers while trying to rescue the Luzia’s fossil.[87][89]

Two fire engines were used with turntable ladders, with two water trucks taking turns to supply water.[83][88] The Brazilian Marine Corps also provided fire engines, water trucks, and a decontamination unit from a nearby base.[90] Pictures on social media showed artifacts being rescued from the burning building by firefighters and civilians.[91]

At 22:00 (01:00 UTC 3 September), dozens of museum employees joined the fight against the flames. Two floors of the building were already destroyed by this time, and the roof had collapsed.[88] Brazilian Culture Minister Sérgio Sá Leitão suggested that it was probably caused by either an electric fault or by a sky lantern accidentally landing on the building.[92]

Damage to collection

A building area of 13600 m² with 122 rooms was destroyed. The building was started on 1803 with luso-lebanese Elie Antun Lubbus.[93] According to museum officials, approximately 92.5 percent of the collection has been destroyed.[94] The building was uninsured.[95]

A spokesman for the fire department reported that pieces had been recovered from the blaze, due to efforts from firefighters and workers from the museum.[96] Information about the condition of pieces that had been displayed started being reported as early as late 2 September, when the images of items had been shared. One of these was a Roman fresco from Pompeii that had survived the eruption of Vesuvius, but was lost in the fire.[97]

Preservation director of the museum João Carlos Nara told reporters that "very little will be left" and that they would "have to wait until the firefighters have completed their work here in order to really assess the scale of it all."[98] The next day, firefighters began more salvage work inside the museum, trying to rescue what they could from beneath the charred remains of the collapsed roof.[99]

The collection relating to indigenous languages is believed to have been completely destroyed, including the recordings since 1958, the chants in all the extinct languages, the Curt Nimuendajú archives (papers, photos, negatives, the original ethnic-historic-linguistic map localizing all the ethnic groups in Brazil, the only extant record from 1945), and the ethnological and archaeological references of all ethnic groups in Brazil since the 16th century.[100] One of the linguistic researchers, Bruna Franchetto, who returned only to see her office as a pile of ash, criticised the fact that a project to back up the collection digitally had only just received funding and barely started, asking for any student who had ever come to the museum to scan or photocopy things for projects to send a copy back.[101]

The fire destroyed the museum's collection of thousands of indigenous artifacts from the country's pre-Columbian Indo-American culture. The items include many indigenous peoples' remains as well as relics amassed in the personal collection of Pedro II.[102][103] This collection also featured items from present native tribes, including "striking feather art by the Karajá people". There are only about 3,000 Karajá people left.[103]

Indigenous people expressed anger that there was no money given to a museum with indigenous history but "the city had recently managed to find a huge budget to build a brand new Museum of Tomorrow".[72] Cira Gonda also confirmed shortly after the fire that the indigenous linguistics collected had been completely destroyed, and so that original recordings of spoken word and song in dead languages have been lost, as well as other artifacts including those detailing the land and language distribution of tribes in Brazil.[100]

Surviving items

Some items survived the fire. The Bendegó meteorite from the museum's collection of meteorites, which is the biggest iron meteorite ever found in Brazil, was unscathed, due to its inherent fire-resistance.[104][105] From images and video of salvage after the fire, at least three other meteorites also survived undamaged.[106][107] Another meteorite called Angra dos Reis was rediscovered among the debris. The meteorite is worth R$ 3 million and was lost in the rubble of the National Museum. With a mass 76 thousand times smaller than that of Bendegó, with mere 65 grams and 4 cm long, Angra dos Reis rock is the most valuable of the collection and was already the object of meteorite hunters. In more than a century of research, this fragment was divided into small portions. The biggest one was buried in the rubble of the museum.[108][109] Some meteorites were found on 19 October 2018, including the Angra dos Reais, besides, burnt.[110]

In the days following the fire, firefighters recovered several portraits from the upper floor of the museum, which had been burnt, smoke and water damaged but not destroyed. Cristiana Serejo, deputy director of the museum, also said that "part of the zoological collection, the library and some ceramics" had survived.[111] Images were shared of research microscopes, freezers, and specimen jars being collected outside of the building by museum staff during the fire, next to a rusted hydrant.[106] During the fire, part of the Zoology department pulled out mollusks and other marine specimens, and only stopped due to the imminent danger the fire posed.[112] The fire did not reach an annex of the site where vertebrate specimens were kept, but due to a loss of electricity parts of the collection could become damaged.[113]

During the salvage, an intact skull that appeared to be that of Luzia Woman was found, and sent to a nearby scientific laboratory for analysis.[114] Due to other skulls and fragments of bones were discovered in the remains of the building prompting a need for lab testing on the found items.[113] On 19 October 2018, it was announced that the Luzia skull indeed was found however as many fragments, which 80% were identified as being part of the frontal (forehead and nose), side, bones that are more resistant and the fragment of a femur that also belonged to the fossil and was stored. A part of the box where Luiza's skull was, was also recovered. Though the assembly of them was postponed.[115] The bones became white, because the earth along them were burned.

A portion of the museum's collection, specifically the herbarium, and fish and reptile species, was housed elsewhere and has not been affected.[116] There was also a large scientific library within the museum, containing thousands of rare works. People on social media were reported to have found burnt pages from the library in the nearby streets;[103] it was later confirmed that the library proper is housed in an adjacent building and was mostly undamaged.[117] Some burnt pages, of unknown origin, were recovered by security guards. Nine Torah scrolls from the 15th century had previously been on display but were in the library at the time and survived.[95]

Reactions

_BHL4958452.jpg)

Brazil's president, Michel Temer, said that "the loss of the National Museum is incalculable for Brazil. Today is a tragic day for our country's museology. Two hundred years of work, research and knowledge were lost. The value of our history cannot be measured now, due to the damage to the building that housed the Royal Family during the Empire. It is a sad day for all Brazilians."[72][118] His statement was echoed by Rio Mayor Marcelo Crivella, who called for rebuilding stating: "It's a national obligation to reconstruct it from the ashes, recompose every detail of the paintings and photos. Even if they are not original, they will continue to be a reminder of the royal family that gave us independence, the empire and the first constitution and national unity".[119]

The archaeologist Zahi Hawass says that the tragedy legitimizes the movement for the repatriation of Egyptian objects in museums around the world and that if museums are not able to guarantee the safety and conservation of the objects, the archaeologist argues that to be returned to the native land. Although the collection of the National Museum was not targeted by Egyptian archaeologists, Hawass says that the destruction of the collection strengthens the movement for the repatriation of objects and that UNESCO observes countries with overseas collections and overseas museums to control them, to ensure that objects are properly protected and restored.[120]

French President Emmanuel Macron expressed his condolences on Twitter at the event. He offered to send experts to help rebuild the museum.[121]

Brazilian environmentalist and politician Marina Silva called the fire "a lobotomy of the Brazilian memory".[72]

News of the fire quickly spread through the city of Rio de Janeiro, and protesters turned up at the gates in the early hours of Monday morning. Initial reports suggested that there were 500 people, forming a chain around the still-smoking building.[99] Some of the protesters tried to climb over fencing into the museum grounds; the police who were called to attend, in full riot gear, threw tear gas bombs into the crowds. The public were later allowed to enter the grounds.[92]

A group of Museum Studies students from the Federal University of the State of Rio de Janeiro called for the public to send in any photographs or videos of the destroyed collections. Their appeal received 14,000 videos, photos, and drawings of the museum's exhibitions within hours.[122]

Cultural institutions

The president of the National Institute of Historic and Artistic Heritage, Kátia Bogéa, said that "It's a national and worldwide tragedy. Everybody can see that this is not a loss for the Brazilian people, but for the whole humanity" and commented that it was "a predictable tragedy, because we've known for a long time that Brazilian cultural heritage has no budget".[118]

Museums around the world sent their condolences. In the UK, the British Library said "our hearts go out to the staff and users of [the National Museum] of Brazil" and called the fire "a reminder of the fragility and preciousness of our shared global heritage";[123] London's Natural History Museum,[124] the Oxford University Museum of Natural History,[125] and the Smithsonian Institution[126] were among other institutions expressing their sorrow. The head of the Australian Museum said that she was "shocked", "devastated", and "distraught".[127] Egypt's Supreme Council of Antiquities expressed both solidarity with the museum and concern over the status of more than 700 ancient Egyptian artifacts that were housed in the building. It offered to send experts, if requested by the Brazilian government, to assist the National Museum in restoring the damaged pieces.[128]

Salvage efforts

On 12 September 2018, work began to implement a plan to temporarily shelter and work with what is currently the ruins of the museum:[129]

- Wooden structures, including a metallic wall, completely surrounding the São Cristovão Palace to protect what remains of the building,

- Containment measures for the building to avoid risk of landslide,

- An improvised roof to protect against rain water,

- Modules and containers outside to serve as temporary research laboratory space.

For this plan, the Brazilian government offered R$9 million as an emergency budget which has since been received by the museum. The company, Concrejato, is contracted to reinstall the walls of the building at a cost of R$8,998,075.66.[130] and Unesco says that the reconstruction would take 10 years to get ready.[131] Researchers are recreating 300 parts of the collection of the National Museum, including the skull of Luzia, with 3D printers. The studies are being resumed in a laboratory of the National Institute of Technology (INT), by master's and doctoral students of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro.[132]

_(20145716190).jpg)

The museum is still doing some festivals called Museu Nacional Vive or Museum lives to public in tents mounted in front of current under construction improvements to the burned headquarters, with exposition of fossils, living snakes and taxidermied animals like Pterosaurs and Armadillo among others. The museum would do a permanent exposition outside. By some estimates, it would take R$100 million to rebuild the main dependencies. With the exception of a few metal cabinets intact, there are only charred fragments. Around 80% of the roof and 60% of the floors have been affected. The one million euro aid announced by Germany would allow the installation of laboratories for analysis of archaeological finds.[133][134][135]

The museum director said there is a collective effort to rebuild the collection, pursue research, and plan the reconstruction of the institution housing six major graduate programs. He reported that classes, thesis defenses and dissertations were resumed and knowledge production did not stop. "The National Museum has lost part of its collection but has not lost the ability to create knowledge and do science," said the director.[136] The social anthropology library, one of the most important in Latin America and totally destroyed by the fire, has received a considerable amount of donations, including the personal library of Rio de Janeiro researcher Gilberto Velho (1945–2012), who was dean of the Department of Anthropology of the museum until his death. Museum zoologists have already gone to the field to collect new specimens in an attempt to repopulate the invertebrate collection, one of the richest (with 5 million copies only in the case of insects) and harder hit by the fire. Before a revamped headquarters is available, Kellner said the museum's intention is to re-display its collection – still considerable – to the public. There is a collective funding campaign to allow the institution's loan back to schools and the plan to revitalize the museum's botanical garden so that it houses a small exhibition that would receive visitors again. "It would be an illusion, even a frivolous thing, to say that the old collection will be reconstituted, but we will continue to fulfill our role," said the director.[137] It was also informed they plan to keep part of ruins as historical exposition with a high modern structure of equipment inside.

According to UFJR dean Roberto Leher, the facade and the exterior of the National Museum is to be preserved in the reconstruction works, but the building could be different. The recovery of the building will take into account a new concept of architecture. The cost would still depend on the concept of the museum. Technicians focus are on 3D modeling and a term of reference. New materials with low-carbon, energy-less, environmentally friendly will be used because it is a science museum. IPHAN has endorsed (since the property is overturned) to do the reconstruction taking this model into account.[138] The new project could be with high roof space or with more slabs, depending the approval of R$100 million or € 22,610,000,00 in the budget of 2019.[139]

In 7 May 2019, the museum presented 27 small pieces found of Egypt collection. The current director took the chance to ask for more money, a minimum of R$1 million to guarantee his services further.[140] In 14 May 2019, the statue of the Bés god about 2,350 years old was found. The piece in rock and glass paste was one of the highlights of the collection.[141]

The roof was finished on 8 June 2019, nine months after the fire. It is 23 m high sustained by 42 truss tower pillars with 30 thousand steel bars and 147 tons of total weight.[142]

Cooperation agreement with the Italian government provides for restoration of damaged parts and long-term loan of Italian parts that would be displayed in the National Museum when it is ready for reopening. Until then, the exhibition would be installed in the Sala Roma of the Consulate General of Italy, in the Center of Rio de Janeiro. The Italian Ministry of Culture would collaborate in the restoration of a Koré, an important Greek female statue, which was found in 1853 in a tomb in Italy, in which Empress Teresa of Bourbon brought dowry of her marriage to Emperor Pedro II of Brazil.[143] However, the director denied to borrow pieces. Instead, he prefers money donations, which is denied by Italian and French governments. Samba Mangueira and Chico Buarque tries with music to help the museum in some way.[144][145]

Reconstruction

During the signing of a protocol of intent for technical-scientific cooperation with the Brazilian Institute of Museums (Ibram), held on 14 May 2019, it was reported that the works of restoration of the patrimony would be initiated in 2019, with an elaborated executive project of the reconstruction of the facades and of the roof, with an endowment of R$1 million. Paulo Amaral, president of Ibram, said that the new concept of the National Museum would probably be announced in April 2020, when the final formatting of the space would be defined, with parts dedicated to the historical collection, contemporary works and equipment.[146][147]

On the first floor of the building was the Francisca Keller Library, which had the largest collection of anthropology and human sciences in South America. To speed up the fundraising process, they are making a crowdfunding campaign on the Benfeitoria platform. The money would be used for the demolition of the interior walls of the space, restoring the floor, finishing and painting, laying the ceiling, making the electrical and air conditioning installation and the restoration of hardware. They expect to get R$129,000 by 12 September 2019.[146][148]

The Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, responsible for the museum, signed on Saturday 31 August 2019 a memorandum of understanding with the Vale Foundation, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the BNDES to create a governance steering committee that can lead the museum's recovery project. Vale provides R$50 million and BNDES R$21.7 million for this reconstruction.[149] The Ministry of Education had allocated R$16 million to the National Museum. Of this total, R$8.9 million was used in emergency works, and the rest for facade and roof projects. The Ministry of Science, Technology, Innovations and Communications contributed R$10 million to acquire equipment for scientific research and infrastructure actions. Germany had donated 230,000 euros so far.[150] After 1 year since the destruction, 44% of the museum's collections had been saved. More than 50 of the 70 areas hit by the fire were searched.

Reconstruction of the facade and roof is expected to take place between the end of 2019 and the beginning of 2020. In the first half of 2020, the salvage of parts of the collection and the start of the inventory process are expected to be completed. R$69 million in public funds for the project. The amount is composed of R$21 million from BNDES (R$3.3 million of which have already been released), R$43 million from the amendment of the Rio de Janeiro bench in the Chamber of Deputies and R$5 million from the Ministry Education.[151]

On 3 October 2019, the museum has about 120 million reais available to make works, coming from funds from parliamentary amendments, the BNDES and Vale. But, the money cannot be used to buy the material needed to continue the rescue, only in the works. In the box of the Association Friends of the National Museum, there are 80 thousand reais in cash, coming from donations, but only R$25 thousand are not yet committed. The Rio de Janeiro Legislative Assembly (Alerj) donated R$20 million to help in the works. Funding are available as project steps are completed.[152]

Donations

_(20146507828).jpg)

- The German Foreign Ministry has offered €1 million in aid to rebuild Brazil's National Museum. This amount was used to buy container-laboratories to investigate specimens. Those equipment were to be located in a donated field nearby Maracanã Stadium.[153] From the initial amount announced, R$180 thousand was delivered. On 21 May 2019 the Director travelled to Germany and France to ask for the rest and more help, because Brazil Government seems not possible to financially further help.[154] From Germany, the second amount of €145 thousand or R$654 thousand was donated.

- Each of 140 geoparks of UNESCO's conservation areas will collect and send a lithic, fossil, or cultural artifact to Brazil. This means 140 objects would complement the future collection.[155]

- On 17 October 2018, Secretary of the Patrimony of the Union, Sidrack Correia confirmed the donation of the area of 49,300 m², that is about a kilometer from the museum, to install laboratories containers in 45 days, budgeted at R$2.2 million, purchased with funds from the TJRJ Pecunary Penalty Fund to be used by museum researchers. It also serves as a center for students visitation. Part of the total, 10 thousand square meters will be for the Justice Court to install its transport area.[156]

- The National Institute of Industrial Property (INPI), linked to the Ministry of Industry, Foreign Trade and Services (MDIC), concluded on 17 October 2018 the donation of 1,164 items, mostly mobile, to the National Museum. The furniture, which includes tables, chairs, workstations, drawers and cabinets, aid in the restructuring of the Museum. The idea of the donation came from the need for the institute to free itself of idle equipment that was in its old headquarters, in Edifício A Noite, located in Praça Mauá, the port area of Rio de Janeiro, to allow the return of the property to the Secretariat of the Patrimony of the Union (SPU), which should have been empty. Part of the furniture was taken to the Botanical Garden of the National Museum, located in Quinta da Boa Vista, where some sectors are working. Others will be used in the direction of the museum, in the services of museology and teaching assistance, and in the departments of invertebrates, geology, paleontology, entomology and ethnology.[157]

- On 24 October 2018, a farmer from Cuiabá donates 780 old Brazilian coins at an average value of R$5 thousand to Rio de Janeiro National Museum.[158] More than R$100 thousand was donated in campaign to museum.

- On 13 November 2018, the Universidade Estadual do Pará donated 514 insects to the Museum, 314 were borrowed from there. Among them were grasshoppers.[159][160]

- On 25 May 2019, Nuuvem, largest gaming platform in Latin America, donated R$16,860 to the National Museum. The two-day income from the game "The Hero's Legend" was reverted to the museum and 500 gamers engaged in the action. The inspiration came from an initiative that Ubisoft created for the game "Assassin's Creed" for the reconstruction of the Cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris.[161]

- Until June 2019, the small donations from several private individuals summed R$323 thousand.[162]

- The British Council donated R$150 thousand for educational exchange.[162]

- The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew would donate in 2020 a collection of relics collected in the Amazon, stored in the British institution for over 150 years. The items were grouped by botanist Richard Spruce, who spent 15 years gathering specimens and making notes while travelling through the forest and brought to Queen Victoria ceremonial tools and objects used by indigenous tribes in the region. His collection, later stored in the Kew Gardens archives, also includes wooden baskets and graters, trumpets, rattles, and ritual headdresses.[163]

- Wilson Saviano, professor at the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, donated 300 pieces, 15 paintings and 40 books from his private collection of contemporary African art.[164]

- Books: In entomology, it had 20 donations that would give about 23,000 items, it was certainly one of the areas that suffered the most. In vertebrates, more than 500 specimens from various areas of Brazil were donated. In geology and paleontology, it had assets seized by the IRS that were destined for the National Museum. Kellner points out that the Francisca Keller Library of the Graduate Program in Social Anthropology, which had 37,000 documents and books and was fully incinerated, is already being rebuilt. About 10,500 volumes had been donated, and another 8,000 were on the way. From France is approximately 700 kilos. At the Central Library the donation of several other books, over 170 kilos.[165]

Political influences

_(20146447960).jpg)

The director of the National Museum, Alexander W. A. Kellner, issued an open letter addressed to presidential candidates Jair Messias Bolsonaro and Fernando Haddad on the evening of 15 October 2018, which, along two pages, reinforces the historical importance of the institution, and recalls that his survival is tied to the responsibility of those who hold "power in the hands."[166]

The document was also sent to the National Congress, where he had regularly gone to ask for a public hearing, during which he asked for the inclusion of resources for the museum, and for the next budget. Without these resources, he says the institution will end up harming decades of research.

In the letter, the director says that many reflect on what could have been done differently to avoid a disaster that led to the loss of an invaluable patrimony, involving millions of cultural and scientific pieces. He also adds that "others should be deeply reflecting on why, being in a position of decision, they did not act firmly in triggering actions that would have avoided the absurdity of that loss".

On 17 October 2018, the Director of the Museum had a meeting with federal deputies to first resolve the R$50 million needed to reinstall the front part of Palace.[167]In late October 2018, the museum's director attended an audience in Brasília at the Chamber of Deputies in order to secure R$56 million for the basic reconstruction of the front part of main building, No. 1, including the facade, roof and its structure. He negotiated the money before the President-elect Jair Bolsonaro, being afraid that the building would remain destroyed for years in an abandoned state. Also, the laboratory containers were not received.[168] On 31 October 2018, the Chamber of Deputies approved an amendment of R$55 million to the budget of 2019. This would need to be further approved by a joint committee and also by the plenary.[169] The Director travelled to China to guarantee pieces of collections for the museum. During his travel to (Germany), specifically Berlin, Munich and Paris, France to bargain some money, the amount of R$55 million, supposed to reconstruct some part of building was reduced to R$43 million by Government.[170] However the Louvre Museum could lend some Egyptian pieces to be displayed in Rio de Janeiro, when its reconstruction comes done. From this sum, until June 2019, Education Ministry or Ministério da Educação (MEC) paid R$908.800,00 for the facade project.[162]

A proposal by Senator Maria do Carmo Alves (DEM-SE) under review in the Commission of Education, Culture and Sport proposes to include a National Day of the Museum, in the official Brazilian calendar to be celebrated on 18 May.[171]

Until December 2018, the concern was the change of the Brazilian Government, because none of the transition teams of the future Governor of Rio de Janeiro, nor the President of the Republic Jair Messias Bolsonaro have sought the direction of the museum to talk about the disaster that hit the former Residence of the Imperial Family. Even then, the containers to store restored objects, until the reconstruction work is completed, had not yet been delivered by the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, which did not express its opinion on the delay.[172]

_(20145700388).jpg)

Recent Events

During the three months after the fire debris was removed, the "economic support network" promised by the president was not established. The partnership to help the museum would count on the participation of the Brazilian Federation of Banks (Febraban), Petrobrás, Bradesco, Itaú, Santander, Caixa, Banco do Brasil, BNDES and Vale. According to the entity, the banks are awaiting approval of Provisional Measure 851 in the National Congress to be able to make the donations. The text must be approved by Congress until February 2019. If this does not happen, the Provisional Measure loses its validity. "The first disbursement of the contract between the BNDES, the Association of Friends of the National Museum and UFRJ, with a total execution period of four years, was scheduled for October 2018 of R$ 3 million."

In June 2018, when the National Museum completed 200 years, the BNDES signed a R$21.7 million contract to pay for the update of the building, but before the first transfer of R$3 million, it caught fire. The agreement was maintained, and the BNDES promised that the money would be used to support the reconstruction works. That was not done. Until final of 2018, only R$8.9 million was released to carry out emergency works for the reconstruction of the building.[173]

The Ministry of Education (MEC) gave R$5 million to a second phase of elaboration of recovery project of the Museum. Unesco personnel and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs visited the debris. Another R$2.5 million was allocated to the research of the institution through the Coordination of Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (Capes).[174]

1,500 items were found among the rubble, between parts of the collection, equipment, personal property and others not unidentifiable. Among them were pieces from the Egyptian collection and minerals from the Werner collection, that came to Brazil along with the Portuguese Crown, as well as pre-Columbian ceramics.

A partnership with Google Brasil, through Google Arts & Culture, allowed guided virtual tours via internet of 160 items from the collections in 2016.[175][176]

See also

- Paço de São Cristóvão, the historic palace that houses the National Museum

- National Historical Museum of Brazil

- List of directors of the National Museum of Brazil

- Wikipedia:Notice on the National Museum

Further reading

- Araujo, Ana Lucia (April 2019). "The Death of Brazil's National Museum". The American Historical Review. 124 (2): 569–580.

References

- "Museus em Números, Vol. 1" (PDF). Instituto Brasileiro de Museus – IBRAM. p. 73. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2015.

- "200 Anos do Museu Nacional" (PDF). Associação Amigos do Museu Nacional. p. 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2017.

- "Museum lives" (in Portuguese). Eco & Youtube. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- "O Museu Nacional é uma instituição autônoma, integra..." (in Portuguese). Museu Nacional Ufrj. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- "Museu Nacional – UFRJ" (in Portuguese). Museus do Rio. 2018. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 15 February 2017. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Grande Enciclopédia Larousse Cultural. Santana de Parnaíba: Banco Safra. 1998. p. 4132.

- "O Museu" (in Portuguese). Museu Nacional - UFRJ. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 15 February 2017. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Arquivos do Museu Nacional Vol. 62 N. 3" (PDF). 2004. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 September 2018. Retrieved 3 September 2018. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "A Revista Arquivos e a Biblioteca do Museu Nacional" (in Portuguese). Revista do Arquivo Nacional. 2018. Archived from the original on 26 April 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2017. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Rio's 200-year-old National Museum hit by massive fire". Reuters. 2 September 2018. Archived from the original on 3 September 2018. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- "Fire engulfs 200-year-old Brazil museum". BBC. 2 September 2018. Archived from the original on 3 September 2018. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- "Incêndio atinge prédio do Museu Nacional, no Rio". UOL Notícias (in Portuguese). 2 September 2018. Archived from the original on 3 September 2018. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- "Lessons from the destruction of the National Museum of Brazil". The Economist. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- "Incêndio que destruiu o Museu Nacional começou no ar-condicionado do auditório, diz laudo da PF". G1 (in Portuguese). 4 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- "Museu Nacional é liberado para ações de prevenção e estabilização". UOL (in Portuguese). 14 September 2018. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- "Mais de 30 mil peças do passado da Família Imperial são encontradas durante obras no RioZoo". G1 (in Portuguese). Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- "Destruído por incêndio, Museu Nacional recebeu R$ 1,1 milhão em doações. Em dois dias, R$ 3 bilhões foram doados para reconstrução da Catedral Notre-Dame, na França". Folha De S.Paulo (in Portuguese). Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- Simon Schwartzman. Space for Science: The Development of the Scientific Community in Brazil. Penn State Press. p. 53. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- Roberts, Edmund (1837). Embassy to the Eastern Courts of Cochin-China, Siam, and Muscat. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 25. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- "Lego". 25 September 2019.

- Sears, P M (1963). "Recovery of the Bendego Meteorite". Meteoritics. 2 (1): 22–23. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- O Museu Nacional. São Paulo: Banco Safra. 2007. p. 45.

- "Departamento de Antropologia" (in Portuguese). Museu Nacional/UFRJ. Archived from the original on 14 February 2017. Retrieved 13 February 2017. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Guia de Exposições do Museu Nacional – Egito Antigo (I)" (in Portuguese). Museu Nacional/UFRJ. Archived from the original on 15 March 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2017. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Barkos, Margaret Marchiori (2004). Egiptomania – O Egito no Brasil. São Paulo: Paris Editorial. pp. 31–35. ISBN 85-72-44261-8.

- O Museu Nacional. São Paulo: Banco Safra. 2007. p. 222.

- Brancaglion Junior, Antonio (2007). Revelando o Passado: estudos da coleção egípcia do Museu Nacional (in In: Lessa, Fábio de Souza & Bustamente, Regina. "Memoria & festa"). Rio de Janeiro: Mauad Editora. pp. 75–80.

- O Museu Nacional. São Paulo: Banco Safra. 2007. pp. 41–42.

- "Múmia Kherima intriga pesquisadores do Museu Nacional". O Globo (in Portuguese). 2016. Archived from the original on 9 February 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- "Guia de Exposições do Museu Nacional – Egito Antigo (II)" (in Portuguese). Museu Nacional/UFRJ. 2016. Archived from the original on 24 April 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2017. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Culturas do Mediterrâneo" (in Portuguese). Museu Nacional/UFRJ. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2017. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - O Museu Nacional. São Paulo: Banco Safra. 2007. p. 238.

- "Italianos restauram afrescos inéditos da coleção Imperatriz Tereza Cristina" (in Portuguese). Agência Brasil. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2017. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Guia de Exposições do Museu Nacional – Culturas Mediterrâneas" (in Portuguese). Museu Nacional/UFRJ. Archived from the original on 1 March 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2017. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - O Museu Nacional. São Paulo: Banco Safra. 2007. p. 19.

- "Projeto da Nova Exposição do Museu Nacional/UFRJ" (PDF) (in Portuguese). Museu Nacional/UFRJ. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 February 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2017. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Guia de Visitação Escolar ao Museu Nacional/UFRJ" (in Portuguese). Museu Nacional/UFRJ. Archived from the original on 14 February 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2017. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - O Museu Nacional. São Paulo: Banco Safra. 2007. p. 43.

- "Cultura Moche" (in Portuguese). Museu Nacional/UFRJ. Archived from the original on 14 February 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2017. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - O Museu Nacional. São Paulo: Banco Safra. 2007. p. 290.

- "Cultura Lambayeque" (in Portuguese). Museu Nacional/UFRJ. Archived from the original on 14 February 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2017. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Cultura Chimu" (in Portuguese). Museu Nacional/UFRJ. Archived from the original on 14 February 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2017. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - O Museu Nacional. São Paulo: Banco Safra. 2007. p. 296.

- "Cultura Chancay" (in Portuguese). Museu Nacional/UFRJ. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2017. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Cultura Inca" (in Portuguese). Museu Nacional/UFRJ. Archived from the original on 14 February 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2017. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - O Museu Nacional. São Paulo: Banco Safra. 2007. p. 304.

- O Museu Nacional. São Paulo: Banco Safra. 2007. p. 308.

- O Museu Nacional. São Paulo: Banco Safra. 2007. p. 309.

- O Museu Nacional. São Paulo: Banco Safra. 2007. p. 334.

- "Arqueologia Brasileira – Artefatos líticos dos primeiros povoadores" (in Portuguese). Guia de Exposições do Museu Nacional. Archived from the original on 3 May 2015. Retrieved 16 February 2017. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - O Museu Nacional. São Paulo: Banco Safra. 2007. p. 261.

- O Museu Nacional. São Paulo: Banco Safra. 2007. pp. 264–275.

- O Museu Nacional. São Paulo: Banco Safra. 2007. p. 282.

- O Museu Nacional. São Paulo: Banco Safra. 2007. pp. 284–285.

- "Arqueologia Brasileira – Miracanguera" (in Portuguese). Guia de Exposições do Museu Nacional. Archived from the original on 28 February 2017. Retrieved 16 February 2017. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - O Museu Nacional. São Paulo: Banco Safra. 2007. pp. 286–289.

- "Arqueologia Brasileira – Cerâmica Tupi-guaran" (in Portuguese). Guia de Exposições do Museu Nacional. Archived from the original on 1 March 2017. Retrieved 16 February 2017. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Só para os íntimos" (in Portuguese). Revista de História. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 16 February 2017. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Lessons from the destruction of the National Museum of Brazil". The Economist. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- Pamplona, Nicola; Alegretti, Laís (2 September 2018). "Incêndio de grandes proporções atinge Museu Nacional na Quinta da Boa Vista, no Rio". Folha de S.Paulo (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 3 September 2018. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- "Fogo destrói Museu Nacional, mais antigo centro de ciência do País". Estadão (in Portuguese). 2 September 2018. Archived from the original on 3 September 2018. Retrieved 3 September 2018.