Fireworks

Fireworks are a class of low explosive pyrotechnic devices used for aesthetic and entertainment purposes. The most common use of a firework is as part of a fireworks display (also called a fireworks show or pyrotechnics), a display of the effects produced by firework devices.

Fireworks take many forms to produce the four primary effects: noise, light, smoke, and floating materials (confetti for example). They may be designed to burn with colored flames and sparks including red, orange, yellow, green, blue, purple, and silver. Displays are common throughout the world and are the focal point of many cultural and religious celebrations.

Fireworks are generally classified as to where they perform, either as a ground or aerial firework. In the latter case they may provide their own propulsion (skyrocket) or be shot into the air by a mortar (aerial shell).

The most common feature of fireworks is a paper or pasteboard tube or casing filled with the combustible material, often pyrotechnic stars. A number of these tubes or cases are often combined so as to make when kindled, a great variety of sparkling shapes, often variously colored. A skyrocket is a common form of firework, although the first skyrockets were used in warfare. The aerial shell, however, is the backbone of today's commercial aerial display, and a smaller version for consumer use is known as the festival ball in the United States. Such rocket technology has also been used for the delivery of mail by rocket and is used as propulsion for most model rockets.

Fireworks were originally invented in China. One of the cultural practices for fireworks was to scare away evil spirits. Cultural events and festivities such as the Chinese New Year and the Mid-Autumn Moon Festival were and still are times when fireworks are guaranteed sights. China is the largest manufacturer and exporter of fireworks in the world.

History

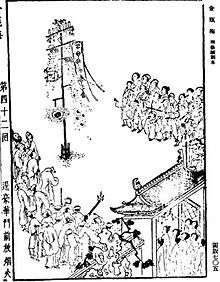

The earliest fireworks came from China during the Song dynasty (960–1279).[3] Fireworks were used to accompany many festivities.[4] The art and science of firework making has developed into an independent profession. In China, pyrotechnicians were respected for their knowledge of complex techniques in mounting firework displays.[5] Chinese people originally believed that the fireworks could expel evil spirits and bring about luck and happiness.[6]

During the Han dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD), people threw bamboo stems into a fire to produce an explosion with a loud sound.[7] In later times, gunpowder packed into small containers was used to mimic the sounds of burning bamboo.[7] These exploding bamboo stems and gunpowder firecrackers were interchangeable known as baozhu (爆竹) or baogan (爆竿).[7] By the 12th and possibly the 11th century, the term baozhang (爆仗) was used to specifically refer to gunpowder firecrackers.[7]

During the Song dynasty (960–1279), many of the common people could purchase various kinds of fireworks from market vendors.[8] Grand displays of fireworks were also known to be held. In 1110, a large fireworks display in a martial demonstration was held to entertain Emperor Huizong of Song (r. 1100–1125) and his court.[9] A record from 1264 states that a rocket-propelled firework went off near the Empress Dowager Gong Sheng and startled her during a feast held in her honor by her son Emperor Lizong of Song (r. 1224–1264).[10] Rocket propulsion was common in warfare, as evidenced by the Huolongjing compiled by Liu Bowen (1311–1375) and Jiao Yu (fl. c. 1350–1412).[11] In 1240 the Arabs acquired knowledge of gunpowder and its uses from China. A Syrian named Hasan al-Rammah wrote of rockets, fireworks, and other incendiaries, using terms that suggested he derived his knowledge from Chinese sources, such as his references to fireworks as "Chinese flowers".[4][12]

In regards to colored fireworks, this was derived and developed from earlier (possibly Han or soon thereafter) Chinese application of chemical substances to create colored smoke and fire.[13] Such application appears in the Huolongjing (14th century) and Wubeizhi (preface of 1621, printed 1628), which describes recipes, several of which used low-nitrate gunpowder, to create military signal smokes with various colors.[13] In the Wubei Huolongjing (武備火龍經; Ming, completed after 1628), two formulas appears for firework-like signals, the sanzhangju (三丈菊) and baizhanglian (百丈蓮), that produces silver sparkles in the smoke.[13] In the Huoxilüe (火戲略; 1753) by Zhao Xuemin (趙學敏), there are several recipes with low-nitrate gunpowder and other chemical substances to tint flames and smoke.[13] These included, for instance, arsenical sulphide for yellow, copper acetate (verdigris) for green, lead carbonate for lilac-white, and mercurous chloride (calomel) for white.[13] The Chinese pyrotechnics have been written about by foreign authors such as Antoine Caillot (1818) who wrote "It is certain that the variety of colours which the Chinese have the secret of giving to flame is the greatest mystery of their fireworks." or Sir John Barrow (ca. 1797) who wrote "The diversity of colours indeed with which the Chinese have the secret of cloathing fire seems to be the chief merit of their pyrotechny."[13]

Fireworks were produced in Europe by the 14th century, becoming popular by the 17th century.[14][15][16] Lev Izmailov, ambassador of Peter the Great, once reported from China: "They make such fireworks that no one in Europe has ever seen."[16] In 1758, the Jesuit missionary Pierre Nicolas le Chéron d'Incarville, living in Beijing, wrote about the methods and composition on how to make many types of Chinese fireworks to the Paris Academy of Sciences, which revealed and published the account five years later.[17][17] Amédée-François Frézier published his revised work Traité des feux d'artice pour le spectacle (Treatise on Fireworks) in 1747 (originally 1706),[18] covering the recreational and ceremonial uses of fireworks, rather than their military uses. Music for the Royal Fireworks was composed by George Frideric Handel in 1749 to celebrate the Peace treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, which had been declared the previous year.

"Prior to the nineteenth century and the advent of modern chemistry they [fireworks]] must have been relatively dull and unexciting."[14] Bertholet in 1786 discovered that oxidations with potassium chlorate resulted in a violet emission. Subsequent developments revealed that oxidations with the chlorates of barium, strontium, copper, and sodium result in intense emission of bright colors. The isolation of metallic magnesium and aluminium marked another breakthrough as these metals burn with an intense silvery light.[14]

Safety

Improper use of fireworks may be dangerous, both to the person operating them (risks of burns and wounds) and to bystanders; in addition, they may start fires after landing on flammable material. For this reason, the use of fireworks is generally legally restricted. Display fireworks are restricted by law for use by professionals; consumer items, available to the public, are smaller versions containing limited amounts of explosive material to reduce potential danger.

Fireworks are also a problem for animals, both domestic and wild, which can be frightened by their noise, leading to them running away, often into danger, or hurting themselves on fences or in other ways in an attempt to escape.[19][20][21]

Competitions

Pyrotechnical competitions involving fireworks are held in many countries. The most prestigious fireworks competition is the Montreal Fireworks Festival, an annual competition held in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Another magnificent competition is Le Festival d'Art Pyrotechnique held in the summer annually at the Bay of Cannes in Côte d'Azur, France. The World Pyro Olympics is an annual competition amongst the top fireworks companies in the world. It is held in Manila, Philippines. The event is one of the largest and most intense international fireworks competitions.

Clubs

Enthusiasts in the United States have formed clubs which unite hobbyists and professionals. The groups provide safety instruction and organize meetings and private "shoots" at remote premises where members shoot commercial fireworks as well as fire pieces of their own manufacture. Clubs secure permission to fire items otherwise banned by state or local ordinances. Competition among members and between clubs, demonstrating everything from single shells to elaborate displays choreographed to music, are held. One of the oldest clubs is Crackerjacks, Inc.,[22] organized in 1976 in the Eastern Seaboard region of the U.S.

PGI annual convention

The Pyrotechnics Guild International, Inc. or PGI,[23] founded in 1969, is an independent worldwide nonprofit organization of amateur and professional fireworks enthusiasts. It is notable for its large number of members, around 3,500 in total. The PGI exists solely to further the safe usage and enjoyment of both professional grade and consumer grade fireworks while both advancing the art and craft of pyrotechnics and preserving its historical aspects. Each August the PGI conducts its annual week-long convention, where some the world's biggest and best fireworks displays occur. Vendors, competitors, and club members come from around the US and from various parts of the globe to enjoy the show and to help out at this all-volunteer event. Aside from the nightly firework shows, the competition is a highlight of the convention. This is a completely unique event where individual classes of hand-built fireworks are competitively judged, ranging from simple fireworks rockets to extremely large and complex aerial shells. Some of the biggest, best, most intricate fireworks displays in the United States take place during the convention week.

Amateur and professional members can come to the convention to purchase fireworks, paper goods, novelty items, non-explosive chemical components and much more at the PGI trade show. Before the nightly fireworks displays and competitions, club members have a chance to enjoy open shooting of any and all legal consumer or professional grade fireworks, as well as testing and display of hand-built fireworks. The week ends with the Grand Public Display on Friday night, which gives the chosen display company a chance to strut their stuff in front of some of the world's biggest fireworks aficionados. The stakes are high and much planning is put into the show. In 1994 a shell of 36 inches (914 mm) in diameter was fired during the convention, more than twice as large as the largest shell usually seen in the US, and shells as large as 24 inches (610 mm) are frequently fired.

Halloween

- Canada

Both fireworks and firecrackers are a popular tradition during Halloween in Vancouver, although apparently this is not the custom elsewhere in Canada.

- Ireland

In the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland there are many fireworks displays, during the Halloween season. The largest are in the cities of Belfast, Derry, and Dublin. The 2010 Derry Halloween fireworks attracted an audience of over 20,000 people.[24] The sale of fireworks is strongly restricted in the Republic of Ireland, though many illegal fireworks are sold throughout October or smuggled from Northern Ireland. In the Republic the maximum punishment for possessing fireworks without a licence, or lighting fireworks in a public place, is a €10,000 fine and a five-year prison sentence.[25]

- United States

Two firework displays on All Hallows' Eve in the United States are the annual "Happy Hallowishes" show at Walt Disney World's Magic Kingdom "Mickey's Not-So-Scary Halloween Party" event, which began in 2005, and the "Halloween Screams" at Disneyland Park, which began in 2009.

Fireworks celebrations throughout the world

Australia

In Australia, fireworks displays are used in the public celebration of major events such as New Year's Eve.

France

In France, fireworks are traditionally displayed on the eve of Bastille day (14 July) to commemorate the French revolution and the storming of the Bastille on that same day in 1789. Every city in France lights up the sky for the occasion with a special mention to Paris that offers a spectacle around the Eiffel Tower.

Hungary

In Hungary fireworks are used on 20 August, which is a national celebration day [26]

India

Indians throughout the world celebrate with fireworks as part of their popular "festival of lights" (Diwali) in Oct-Nov every year.

Japan

During the summer in Japan, fireworks festivals (花火大会, hanabi taikai) are held nearly every day someplace in the country, in total numbering more than 200 during August. The festivals consist of large fireworks shows, the largest of which use between 100,000 and 120,000 rounds (Tondabayashi, Osaka), and can attract more than 800,000 spectators. Street vendors set up stalls to sell various drinks and staple Japanese food (such as Yakisoba, Okonomiyaki, Takoyaki, Kakigōri (shaved ice), and traditionally held festival games, such as Kingyo-sukui, or Goldfish scooping.

Even today, men and women attend these events wearing the traditional Yukata, summer Kimono, or Jinbei (men only), collecting in large social circles of family or friends to sit picnic-like, eating and drinking, while watching the show.

The first fireworks festival in Japan was held in 1733.[27]

Sumidagawa Fireworks Festival is one of the many being celebrated annually throughout Japan in summer.

Malta

Fireworks have been used in Malta for hundreds of years. When the islands were ruled by the Order of St John, fireworks were used on special occasions such as the election of a new Grand Master, the appointment of a new Pope or the birth of a prince.[28]

Nowadays, fireworks are used in village feasts throughout the summer. The Malta International Fireworks Festival is also held annually.[29]

Monte-Carlo International Fireworks Festival

Pyrotechnics experts from around the world have competed in Monte Carlo, Monaco since 1966. The festival runs from July to August every year, and the winner returns in 18 November for the fireworks display on the night before the National Day of Monaco.[30] The event is held in Port Hercule, beginning at around 9:30pm every night, depending on the sunset.[31]

Singapore

The Singapore Fireworks Celebrations (previously the Singapore Fireworks Festival) is an annual event held in Singapore as part of its National Day celebrations. The festival features local and foreign teams which launch displays on different nights. While currently non-competitive in nature, the organizer has plans to introduce a competitive element in the future.

The annual festival has grown in magnitude, from 4,000 rounds used in 2004, to 6,000 in 2005, to over 9,100 in 2006.

South Korea

Busan International Fireworks Festival is one of the most significant fireworks festivals in Asia.

Switzerland

In Switzerland fireworks are often used on 1 August, which is a national celebration day.[32]

United Kingdom

One of the biggest occasions for fireworks in the UK is Guy Fawkes Night held each year on 5 November, to celebrate the foiling of the Catholic Gunpowder Plot on 5 November 1605, an attempt to kill King James I. The Guardian newspaper said in 2008 that Britain's biggest Guy Fawkes night events were:[33]

- After Dark fireworks, Sheffield homepage

- Bangers on the Beach (Holyhead Round Table charity fireworks), Holyhead homepage

- Battel Bonfire in Battle, East Sussex homepage

- Blackheath Fireworks, London homepage

- Bught Park fireworks, Inverness homepage

- Fireworks with Vikings, Tutbury, Staffordshire homepage

- Flaming Tar Barrels, Ottery St Mary homepage

- Glasgow Green fireworks homepage

- Halloween Happening fireworks, Derry homepage

- Midsummer Common, Cambridge homepage

- Sparks in the Park (Cardiff Round Table charity fireworks), Cardiff homepage

The main firework celebrations in the UK are by the public who buy from many suppliers.

United States

America's earliest settlers brought their enthusiasm for fireworks to the United States. Fireworks and black ash were used to celebrate important events long before the American Revolutionary War. The very first celebration of Independence Day was in 1777, six years before Americans knew whether or not the new nation would survive the war; fireworks were a part of all festivities. In 1789, George Washington's inauguration was accompanied by a fireworks display. This early fascination with fireworks' noise and color continues today with fireworks displays commonly included in Independence Day celebrations.

In 2004, Disneyland, in Anaheim, California, pioneered the commercial use of aerial fireworks launched with compressed air rather than gunpowder. The display shell explodes in the air using an electronic timer. The advantages of compressed air launch are a reduction in fumes, and much greater accuracy in height and timing.[34] The Walt Disney Company is now the largest consumer of fireworks in the United States.

Uses other than public displays

In addition to large public displays, people often buy small amounts of fireworks for their own celebrations. Fireworks on general sale are usually less powerful than professional fireworks. Types include firecrackers, rockets, cakes (multishot aerial fireworks) and smoke balls.

Fireworks can also be used in an agricultural capacity as bird scarers.

Pyrotechnic compounds

Colors in fireworks are usually generated by pyrotechnic stars—usually just called stars—which produce intense light when ignited. Stars contain five basic types of ingredients.

- A fuel

- An oxidizer—a compound that combines with the fuel to produce intense heat

- Color-producing salts (when the fuel itself is not the colorant)

- A binder which holds the pellet together.

Some of the more common color-producing compounds are tabulated here. The color of a compound in a firework will be the same as its color in a flame test (shown at right). Not all compounds that produce a colored flame are appropriate for coloring fireworks, however. Ideal colorants will produce a pure, intense color when present in moderate concentration.

The color of sparks is limited to red/orange, yellow/gold and white/silver. This is explained by light emission from an incandescent solid particle in contrast to the element-specific emission from the vapor phase of a flame.[35] Light emitted from a solid particle is defined by black-body radiation. Low boiling metals can form sparks with an intensively colored glowing shell surrounding the basic particle.[36] This is caused by vapor phase combustion of the metal.

| Color | Metal | Example compounds |

|---|---|---|

| Red | Strontium (intense red)

Lithium (medium red) |

SrCO3 (strontium carbonate)

Li2CO3 (lithium carbonate) LiCl (lithium chloride) |

| Orange | Calcium | CaCl2 (calcium chloride) |

| Yellow | Sodium | NaNO3 (sodium nitrate) |

| Green | Barium | BaCl2 (barium chloride) |

| Blue | Copper halides | CuCl2 (copper chloride), at low temperature |

| Indigo | Caesium | CsNO3 (caesium nitrate) |

| Violet | Potassium

Rubidium (violet-red) |

KNO3 (potassium nitrate)

RbNO3 (rubidium nitrate) |

| Gold | Charcoal, iron, or lampblack | |

| White | Titanium, aluminium, beryllium, or magnesium powders | |

The brightest stars, often called Mag Stars, are fueled by aluminium. Magnesium is rarely used in the fireworks industry due to its lack of ability to form a protective oxide layer. Often an alloy of both metals called magnalium is used.

Many of the chemicals used in the manufacture of fireworks are non-toxic, while many more have some degree of toxicity, can cause skin sensitivity, or exist in dust form and are thereby inhalation hazards. Still others are poisons if directly ingested or inhaled.

Common elements in pyrotechnics

The following table lists the principal elements used in modern pyrotechnics. Some elements are used in their elemental form such as particles of titanium, aluminium, iron, zirconium, and magnesium. These elements burn in the presence of air (O2) or oxidants (perchlorate, chlorate). Most elements in pyrotechnics are in the form of salts.[14]

| Symbol | Name | Fireworks Usage |

|---|---|---|

| Aluminium | Aluminium metal is used to produce silver and white flames and sparks. It is a common component of sparklers. | |

| Barium | Barium salts are used to create green colors in fireworks, and it can also help stabilize other volatile elements. | |

| Carbon | Carbon is one of the main components of black powder, which is used as a propellent in fireworks. Carbon provides the fuel for a firework. Common forms include carbon black, sugar, or starch. | |

| Chlorine | Chlorate and perchlorates are common oxidizers. | |

| Copper | Copper compounds produce blue colors. | |

| Iron | Iron powder is used to produce sparks in sparklers. | |

| Potassium | Potassium nitrate, potassium chlorate, and potassium perchlorate are common oxidizers. The potassium content impart a faint violet color to the sparks. | |

| Magnesium | Magnesium metal burns a very bright white, so it is used to add white sparks or improve the overall brilliance of a firework. | |

| Sodium | Sodium imparts a gold or yellow color to fireworks, however, the color is often so bright that it frequently masks other, less intense colors. Sodium lamps operate with the same optical emission. | |

| Oxygen | Oxygen is a component of chlorate and perchlorate, common oxidizers. | |

| Sulfur | Sulfur is a component of black powder, and as such, it is found in a propellant/fuel. | |

| Strontium | Strontium salts impart a red color. | |

| Titanium | Titanium metal can be burned as powder or flakes to produce silver sparks. | |

| Zirconium | Zirconium, like titanium, burns to produce oxides that emit brightly. It is used in "waterfalls". |

Types of effects

Cake

A cake is a cluster of individual tubes linked by fuse that fires a series of aerial effects. Tube diameters can range in size from 1⁄4–4 inches (6.4–101.6 mm), and a single cake can have over 1,000 shots. The variety of effects within individual cakes is often such that they defy descriptive titles and are instead given cryptic names such as "Bermuda Triangle", "Pyro Glyphics", "Waco Wakeup", and "Poisonous Spider", to name a few. Others are simply quantities of 2.5–4 in (64–102 mm) shells fused together in single-shot tubes.

Crossette

A shell containing several large stars that travel a short distance before breaking apart into smaller stars, creating a crisscrossing grid-like effect. Strictly speaking, a crossette star should split into 4 pieces which fly off symmetrically, making a cross. Once limited to silver or gold effects, colored crossettes such as red, green, or white are now very common.

Chrysanthemum

A spherical break of colored stars, similar to a peony, but with stars that leave a visible trail of sparks.

Dahlia

Essentially the same as a peony shell, but with fewer and larger stars. These stars travel a longer-than-usual distance from the shell break before burning out. For instance, if a 3 in (76 mm) peony shell is made with a star size designed for a 6 in (152 mm) shell, it is then considered a dahlia. Some dahlia shells are cylindrical rather than spherical to allow for larger stars.

Diadem

A type of Chrysanthemum or Peony, with a center cluster of non-moving stars, normally of a contrasting color or effect.

Fish

Inserts that propel themselves rapidly away from the shell burst, often resembling fish swimming away.

Horsetail

Named for the shape of its break, this shell features heavy long-burning tailed stars that only travel a short distance from the shell burst before free-falling to the ground. Also known as a waterfall shell. Sometimes there is a glittering through the "waterfall".

Kamuro

Kamuro is a Japanese word meaning "boys haircut", which is what this shell resembles when fully exploded in the air. It is a dense burst of glittering silver or gold stars which leave a heavy glitter trail and shine bright in the night's sky.

Mine

A mine (aka. pot à feu) is a ground firework that expels stars and/or other garnitures into the sky. Shot from a mortar like a shell, a mine consists of a canister with the lift charge on the bottom with the effects placed on top. Mines can project small reports, serpents, small shells, as well as just stars. Although mines up to 12 inches (305 mm) diameter appear on occasion, they are usually between 3–5 inches (76–127 mm), in diameter.

Multi-break shells

A large shell containing several smaller shells of various sizes and types. The initial burst scatters the shells across the sky before they explode. Also called a bouquet shell. When a shell contains smaller shells of the same size and type, the effect is usually referred to as "Thousands". Very large bouquet shells (up to 48 inches [1,219 mm]) are frequently used in Japan.

Noise-related effects

- Bang

The bang is the most common effect in fireworks and sounds like a gunshot; technically a "report". - Crackle

The firework produces a crackling sound. - Hummer

Tiny tube fireworks that are ejected into the air spinning with such force that they shred their outer coating, in doing so they whizz and hum. - Whistle

High pitched often very loud screaming and screeching created by the resonance of gas. This is caused by a very fast strobing (on/off burning stage) of the fuel. The rapid bursts of gas from the fuel vibrate the air many hundreds of times per second causing the familiar whistling sound. It is not, as is commonly thought, made in the conventional way that musical instruments are using specific tube shapes or apertures. Common whistle fuels contain benzoate or salicylate compounds and a suitable oxidizer such as potassium perchlorate.

Palm

A shell containing a relatively few large comet stars arranged in such a way as to burst with large arms or tendrils, producing a palm tree-like effect. Proper palm shells feature a thick rising tail that displays as the shell ascends, thereby simulating the tree trunk to further enhance the "palm tree" effect. One might also see a burst of color inside the palm burst (given by a small insert shell) to simulate coconuts.

Peony

A spherical break of colored stars that burn without a tail effect. The peony is the most commonly seen shell type.

Ring

A shell with stars specially arranged so as to create a ring. Variations include smiley faces, hearts, and clovers.

Roman candle

A Roman candle is a long tube containing several large stars which fire at a regular interval. These are commonly arranged in fan shapes or crisscrossing shapes, at a closer proximity to the audience. Some larger Roman candles contain small shells (bombettes) rather than stars.

Salute

A shell intended to produce a loud report rather than a visual effect. Salute shells usually contain flash powder, producing a quick flash followed by a very loud report. Titanium may be added to the flash powder mix to produce a cloud of bright sparks around the flash. Salutes are commonly used in large quantities during finales to create intense noise and brightness. They are often cylindrical in shape to allow for a larger payload of flash powder, but ball shapes are common and cheaper as well. Salutes are also called Maroons.

Spider

A shell containing a fast burning tailed or charcoal star that is burst very hard so that the stars travel in a straight and flat trajectory before slightly falling and burning out. This appears in the sky as a series of radial lines much like the legs of a spider.

Time Rain

An effect created by large, slow-burning stars within a shell that leave a trail of large glittering sparks behind and make a sizzling noise. The "time" refers to the fact that these stars burn away gradually, as opposed to the standard brocade "rain" effect where a large amount of glitter material is released at once.

Willow

Similar to a chrysanthemum, but with long-burning silver or gold stars that produce a soft, dome-shaped weeping willow-like effect.

Hazards and regulation

Safety

Fireworks pose risks of injury to people, and of damage, largely as a fire hazard.

Pollution

Fireworks produce smoke and dust that may contain residues of heavy metals, sulfur-coal compounds and some low concentration toxic chemicals. These by-products of fireworks combustion will vary depending on the mix of ingredients of a particular firework. (The color green, for instance, may be produced by adding the various compounds and salts of barium, some of which are toxic, and some of which are not.) Some fishers have noticed and reported to environmental authorities that firework residues can hurt fish and other water-life because some may contain toxic compounds such as antimony sulfide. This is a subject of much debate due to the fact that large-scale pollution from other sources makes it difficult to measure the amount of pollution that comes specifically from fireworks. The possible toxicity of any fallout may also be affected by the amount of black powder used, type of oxidizer, colors produced and launch method.

Perchlorate salts, when in solid form, dissolve and move rapidly in groundwater and surface water. Even in low concentrations in drinking water supplies, perchlorate ions are known to inhibit the uptake of iodine by the thyroid gland. As of 2010, there are no federal drinking water standards for perchlorates in the United States, but the US Environmental Protection Agency has studied the impacts of perchlorates on the environment as well as drinking water.[37]

Several US states have enacted drinking water standard for perchlorates, including Massachusetts in 2006. California's legislature enacted AB 826, the Perchlorate Contamination Prevention Act of 2003, requiring California's Department of Toxic Substance Control (DTSC) to adopt regulations specifying best management practices for perchlorate-containing substances. The Perchlorate Best Management Practices were adopted on 31 December 2005 and became operative on 1 July 2006.[38] California issued drinking water standards in 2007. Several other states, including Arizona, Maryland, Nevada, New Mexico, New York, and Texas have established non-enforceable, advisory levels for perchlorates.

The courts have also taken action with regard to perchlorate contamination. For example, in 2003, a federal district court in California found that Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA) applied because perchlorate is ignitable and therefore a "characteristic" hazardous waste.[39]

Pollutants from fireworks raise concerns because of potential health risks associated with hazardous by-products. For most people the effects of exposure to low levels of toxins from many sources over long periods are unknown. For persons with asthma or multiple chemical sensitivity the smoke from fireworks may aggravate existing health problems.[40] Environmental pollution is also a concern because heavy metals and other chemicals from fireworks may contaminate water supplies and because fireworks combustion gases might contribute to such things as acid rain which can cause vegetation and even property damage. However, gunpowder smoke and the solid residues are basic, and as such the net effect of fireworks on acid rain is debatable. The carbon used in fireworks is produced from wood and does not lead to more carbon dioxide in the air. What is not disputed is that most consumer fireworks leave behind a considerable amount of solid debris, including both readily biodegradable components as well as nondegradable plastic items. Concerns over pollution, consumer safety, and debris have restricted the sale and use of consumer fireworks in many countries. Professional displays, on the other hand, remain popular around the world.

Others argue that alleged concern over pollution from fireworks constitutes a red herring, since the amount of contamination from fireworks is minuscule in comparison to emissions from sources such as the burning of fossil fuels. In the US, some states and local governments restrict the use of fireworks in accordance with the Clean Air Act which allows laws relating to the prevention and control of outdoor air pollution to be enacted. Few governmental entities, by contrast, effectively limit pollution from burning fossil fuels such as diesel fuel or coal. Coal-fueled electricity generation alone is a much greater source of heavy metal contamination in the environment than fireworks.

Some companies within the U.S. fireworks industry claim they are working with Chinese manufacturers to reduce and ultimately hope to eliminate of the pollutant perchlorate.[41]

Government regulations around the world

Australia

In Australia, Type 1 fireworks are permitted to be sold to the public. For anything that has a large explosion or gets airborne, users need to register for a Type 2 Licence. On 24 August 2009 the ACT Government announced a complete ban on backyard fireworks.[42] The Northern Territory allows fireworks to be sold to residents 18 years or older in the days leading up to Northern Territory Day (1 July) for personal purposes. The types of fireworks allowed for sale is restricted to quieter fireworks, which can only be used at the address provided to the seller.

Canada

.jpg)

The use, storage and sale of commercial-grade fireworks in Canada is licensed by Natural Resources Canada's Explosive Regulatory Division (ERD). Unlike their consumer counterpart, commercial-grade fireworks function differently, and come in a wide range of sizes from 50 mm (2 inches) up to 300 mm (11 13⁄16 inches) or more in diameter. Commercial grade fireworks require a Fireworks Operator Certificate (FOC), obtained from the ERD by completing a one-day safety course. There are two categories of FOC: one for pyrotechnics (those used on stage and in movies) and another for display fireworks (those used in dedicated fireworks shows). Each requires completion of its own course, though there are special categories of FOC which allow visiting operators to run their shows with the assistance of a Canadian supervisor.

The display fireworks FOC has 2 levels: assistant (which allows you to work under a qualified supervisor until you are familiar with the basics), and fully licensed. A fully licensed display fireworks operator can also be further endorsed for marine launch, flying saucers, and other more technically demanding fireworks displays.

The pyrotechnician FOC has 3 levels: pyrotechnician (which allows work under a supervisor), supervising pyrotechnician, and special effects pyrotechnician (which allows the fabrication of certain types of pyrotechnic devices). Additionally, a special effects pyrotechnician can be endorsed for the use of detonating cord.

Since commercial-grade fireworks are shells which are loaded into separate mortars by hand, there is danger in every stage of the setup.[43] Setup of these fireworks involves the placement and securing of mortars on wooden or wire racks; loading of the shells; and if electronically firing, wiring and testing. The mortars are generally made of FRE (fiber-reinforced epoxy) or HDPE (high-density polyethelene). Older mortars made of sheet steel have been banned by most countries due to the problem of shrapnel produced during a misfire.

Setup of mortars in Canada for an oblong firing site require that a mortar be configured at an angle of 10 to 15 degrees down-range with a safety distance of at least 200 meters (660 ft) down-range and 100 meters (330 ft) surrounding the mortars, plus distance adjustments for wind speed and direction. In June 2007, the ERD approved circular firing sites for use with vertically fired mortars with a safety distance of at least 175-meter (574 ft) radius, plus distance adjustments for wind speed and direction.[44]

Loading of shells is a delicate process, and must be done with caution, and a loader must ensure not only the mortar is clean, but also make sure that no part of their body is directly over the mortar in case of a premature fire. Wiring the shells is a painstaking process; whether the shells are being fired manually or electronically, any "chain fusing" or wiring of electrical ignitors, care must be taken to prevent the fuse (an electrical match, often incorrectly called a squib) from igniting. If the setup is wired electrically, the electrical matches are usually plugged into a "firing rail" or "breakout box" which runs back to the main firing board; from there, the Firing Board is simply hooked up to a car battery, and can proceed with firing the show when ready.

Since commercial-grade fireworks are so much larger and more powerful, setup and firing crews are always under great pressure to ensure they safely set up, fire, and clean up after a show.

Chile

In Chile, the manufacture, importation, possession and use of fireworks is prohibited to unauthorized individuals; only certified firework companies can legally use fireworks. As they are considered a type of explosive, offenders can in principle be tried before military courts, though this is unusual in practice.

European Union

.jpg)

The European Union's policy is aimed at harmonising and standardising the EU member states' policies on the regulation of production, transportation, sale, consumption and overall safety of fireworks across Europe.[45]

Belgium

In Belgium, each municipality can decide how to regulate fireworks. During New Year's Eve, lighting fireworks without a licence is allowed in 35% of the 308 Flemish municipalities, in around 50% a permit from the burgemeester (mayor) is required, and around 14% of municipalities have banned consumer fireworks altogether.[46]

Finland

In Finland those under 18 years old haven't been allowed to buy any fireworks since 2009. Safety goggles are required. The use of fireworks is generally allowed on the evening and night of New Year's Eve, 31 December. In some municipalities of Western Finland it is allowed to use fireworks without a fire station's permission on the last weekend of August. With the fire station's permission, fireworks can be used year-round.

Germany

In Germany, amateurs over 18 years old are allowed to buy and ignite fireworks of Category F2 for several hours on 31 December and 1 January; each German municipality is authorised to limit the number of hours this may last locally.[47] The sale of Category F3 and F4 fireworks to consumers is prohibited.[46] Lighting fireworks is forbidden near churches, hospitals, retirement homes and wooden or thatch-roofed buildings.[46] All major German cities organise professional fireworks shows.[46]

Netherlands

In the Netherlands, fireworks cannot be sold to anyone under the age of 16. It may only be sold during a period of three days before a new year. If one of these days is a Sunday, that day is excluded from sale and sale may commence one day earlier.[48]

Republic of Ireland

In the Republic of Ireland, fireworks are illegal and possession is punishable by huge fines and/or prison. However, around Halloween a large amount of fireworks are set off, due to the ease of being able to purchase from Northern Ireland.

Sweden

In Sweden, fireworks can only be purchased and used by people 18 or older. Fire crackers used to be banned, but are now allowed under European Union fireworks policy.

United Kingdom

Fireworks in the UK have become more strictly regulated since 1997. Since 2005, the law has been gradually harmonised in accordance with other EU member states' laws.

Fireworks are mostly used in England, Scotland and Wales around Diwali, in late October or early November, and Guy Fawkes Night, 5 November. In the UK, responsibility for the safety of firework displays is shared between the Health and Safety Executive, fire brigades and local authorities. Currently, there is no national system of licensing for fireworks operators, but in order to purchase display fireworks, operators must have licensed explosives storage and public liability insurance.

Fireworks cannot be sold to people under the age of 18 and are not permitted to be set off between 11pm and 7am with exceptions only for:

- Bonfire Night (5 November) (permitted until midnight)[49]

- The Chinese New Year (permitted until 1am)[49]

- Diwali (permitted until 1am)[49]

- New Year (permitted until midnight New Year's Eve, and continuing to be permitted until 1am)[49]

The maximum legal NEC (net explosive content) of a UK firework available to the public is two kilograms. Jumping jacks, strings of firecrackers, shell firing tubes, bangers and mini-rockets were all banned during the late 1990s. In 2004, single-shot air bombs and bottle rockets were banned, and rocket sizes were limited. From March 2008 any firework with over 5% flashpowder per tube has been classified 1.3G. The aim of these measures was to eliminate "pocket money" fireworks, and to limit the disruptive effects of loud bangs.

Iceland

In Iceland, the Icelandic law states that anyone may purchase and use fireworks during a certain period around New Year's Eve. Most places that sell fireworks in Iceland make their own rules about age of buyers, usually it is around 16. The people of Reykjavík spend enormous sums of money on fireworks, most of which are fired as midnight approaches on 31 December. As a result, every New Year's Eve the city is lit up with fireworks displays.

New Zealand

Fireworks in New Zealand are available from 2 to 5 November, around Guy Fawkes Day, and may be purchased only by those 18 years of age and older (up from 14 years pre-2007). Despite the restriction on when fireworks may be sold, there is no restriction regarding when fireworks may be used. The types of fireworks available to the public are multi-shot "cakes", Roman candles, single shot shooters, ground and wall spinners, fountains, cones, sparklers, and various novelties, such as smoke bombs and Pharaoh's serpents. Consumer fireworks are also not allowed to be louder than 90 decibels.[50]

Norway

In Norway, fireworks can only be purchased and used by people 18 or older. Sale is restricted to a few days before New Year's Eve. Rockets are not allowed.[51]

United States

In the United States, the laws governing fireworks vary widely from state to state, or from county to county. Federal, state, and local authorities govern the use of display fireworks in the United States. At the federal level, the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) regulates consumer fireworks through the Federal Hazardous Substances Act (FHSA). The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) sets forth a set of codes which give the minimum standards of display fireworks use and safety in the US. Both state and local jurisdictions can further add restrictions on the use and safety requirements of display fireworks. There are currently 46 states in the United States in which fireworks are legal for consumer use.[52]

References

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 5: Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 7: Military Technology: The Gunpowder Epic. Cambridge University Press. p. 140. ISBN 0-521-30358-3.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 5: Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 7: Military Technology: The Gunpowder Epic. Cambridge University Press. p. 142. ISBN 0-521-30358-3.

- Gernet, Jacques (1962). Daily Life in China on the Eve of the Mongol Invasion, 1250–1276. Translated by H.M. Wright. Stanford: Stanford University Press. Page 186. ISBN 0-8047-0720-0.

- Temple, Robert K.G. (2007). The Genius of China: 3,000 Years of Science, Discovery, and Invention (3rd edition). London: André Deutsch, pp. 256–266. ISBN 978-0-233-00202-6

- Hutchins, Paul (2009). The secret doorway: Beyond imagination. Imagination Publishing. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-9817123-3-8.

- "Lidu Fireworks". cctv.com. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 5: Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 7: Military Technology: The Gunpowder Epic. Cambridge University Press. p. 128–131. ISBN 0-521-30358-3.

- Gernet, Jacques (1962). Daily Life in China on the Eve of the Mongol Invasion, 1250–1276. Translated by H.M. Wright. Stanford: Stanford University Press, pp. 186. ISBN 0-8047-0720-0.

- Kelly, Jack (2004). Gunpowder: Alchemy, Bombards, and Pyrotechnics: The History of the Explosive that Changed the World. New York: Basic Books, Perseus Books Group, page 2.

- Crosby, Alfred W. (2002), Throwing Fire: Projectile Technology Through History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-79158-8. Pages 100–103.

- Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 489–503.

- Kelly, Jack (2004). Gunpowder: Alchemy, Bombards, & Pyrotechnics: The History of the Explosive that Changed the World. Basic Books, page 22. ISBN 0-465-03718-6.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 5: Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 7: Military Technology: The Gunpowder Epic. Cambridge University Press. pp. 144–146. ISBN 0-521-30358-3.

- T. T. Griffiths, U. Krone, R. Lancaster (2017). "Pyrotechnics". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a22_437.pub2.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "The Evolution of Fireworks", Smithsonian Science Education Center. ssec.si.edu.

- Werrett, Simon (2010). Fireworks: Pyrotechnic arts and sciences in European history. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-226-89377-8.

- Werrett, Simon (2010). Fireworks: Pyrotechnic arts and sciences in European history. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 183. ISBN 978-0-226-89377-8.

- Werrett, Simon (2010). Fireworks: Pyrotechnic arts and sciences in European history. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 144–145. ISBN 978-0-226-89377-8.

- "Fireworks Frighten Animals". Animal Aid. 26 October 2007. Archived from the original on 17 September 2010. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- "Fireworks Thunder and Pets - Safety considerations for noise phobias - fireworks and thunder". Vetmedicine.about.com. Archived from the original on 30 August 2009. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- "How should I care for my pets during fireworks displays? - RSPCA Australia knowledgebase". Kb.rspca.org.au. 17 August 2009. Archived from the original on 13 November 2009. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- "CrackerJacks". Archived from the original on 23 May 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- "PGI (Pyrotechnics Guild International)". Archived from the original on 17 May 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- "Banks of the Foyle Halloween Carnival". Derry City. 2010. Archived from the original on 21 July 2006. Retrieved 5 September 2006.

- Barry, Aoife (27 October 2013). "Warning over fireworks danger – and €10,000 fine for using them illegally". The Journal. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- 20. August-St. Stephen’s Day https://www.budapestbylocals.com/event/august-20th/ Archived 13 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine 20170823

- "Summer: the season of 'fire flowers' - The Japan Times". The Japan Times. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- "The History of Fireworks in Malta". uniqueholidaymalta.com. Archived from the original on 8 February 2015. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- "Festas in Malta & Gozo". malta.com. Archived from the original on 14 February 2015. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- "Monaco - July/August: Monte-Carlo International Fireworks Festival / Annual Events / Plan your stay / Site officiel de Monaco". www.visitmonaco.com. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- "#Monaco's International #Fireworks Festival is back this July and August". Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- "Take care around fireworks, Swiss told". 26 July 2016. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- Wills, Dixe (30 October 2008). "10 best bonfire night celebrations in the UK". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- Walt Disney Company (28 June 2004). "Disney debuts new safer, quieter and more environmentally-friendly fireworks technology". Press Release.

- Kenneth L. Kosanke; Bonnie J. Kosanke (1999), "Pyrotechnic Spark Generation", Journal of Pyrotechnics: 49–62, ISBN 978-1-889526-12-6

- Lederle, Felix; Koch, Jannis; Hübner, Eike G. (21 February 2019). "Colored Sparks". European Journal of Inorganic Chemistry. 2019 (7): 928–937. doi:10.1002/ejic.201801300.

- "Perchlorate | Drinking Water Contaminants | Safewater | Water | US EPA". Epa.gov. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- "Perchlorate". Dtsc.ca.gov. Archived from the original on 23 August 2009. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- Castaic Lake Water Agency v. Whittaker, 272 F. Supp. 2d 1053, 1059-61 (C.D. Cal. 2003)

- New Scientist - Great fireworks, shame about the toxic fallout

- Knee, Karen. Philadelphia Inquirer. 4 Jul 2009. Pa. company works to make fireworks greener

- "Cracker down: ACT bans fireworks". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 24 August 2009. Retrieved 24 August 2009.

- Natural Resources Canada, Explosive Regulatory Division. Display Fireworks Manual (March 2002 Edition)

- Natural Resources Canada Explosive Branch Bulletin #48

- Eliza Bergman & Dirk Bayens (2 January 2014). "Wereldkampioen vuurwerk". Brandpunt Reporter (in Dutch). KRO-NCRV. Archived from the original on 26 December 2017. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- "Veiligheidsrisico's jaarwisseling" (PDF). Dutch Safety Board. 1 December 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- Daniela Siebert (27 December 2017). "Sicher durch die Silvesternacht". Deutschlandfunk (in German). Archived from the original on 29 December 2017. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- "Article 2.3.5 of the Besluit van 22 januari 2002, houdende nieuwe regels met betrekking tot consumenten- en professioneel vuurwerk (Vuurwerkbesluit) Decision of January 22, 2002, laying down new rules on consumer and professional fireworks (Fireworks Decision)". Vuurwerkbesluit (in Dutch). 22 January 2002. Archived from the original on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 20 April 2009. Google Translate Archived 22 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- Statutory Instrument 2004 No. 1836 The Fireworks Regulations 2004, United Kingdom.

- "Fireworks - Know The Rules". Epa.govt.nz. NZ Environmental Protection Agency. 2015. Archived from the original on 2016-01-26. Retrieved November 2015. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - "Norsk brannvernforening: Trygg bruk av fyrverkeri". Archived from the original on 21 October 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- "46 States Where Fireworks Are Legal as July 4 Approaches". InvestorPlace. 3 July 2018. Archived from the original on 11 December 2018. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- Quote from Dave Whysall of Dave Whysall's International Fireworks located in Orton, ON. www.dwfireworks.com

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fireworks. |

Further reading

- Melanie Doderer-Winkler, "Magnificent Entertainments: Temporary Architecture for Georgian Festivals" (London and New Haven, Yale University Press for The Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, December 2013). ISBN 0300186428 and ISBN 978-0300186420.

- Plimpton, George (1984). Fireworks: A History and Celebration. Doubleday. ISBN 0385154143.

- Brock, Alan St. Hill (1949). A History of Fireworks. George G. Harrap & Co.

- Russell, Michael S (2008). The chemistry of fireworks. Royal Society of Chemistry, Great Britain. ISBN 9780854041275.

- Shimizu, Takeo (1996). Fireworks: The Art, Science, and Technique. Pyrotechnica Publications. ISBN 978-0929388052.

- Werrett, Simon (2010). Fireworks: Pyrotechnic Arts and Sciences in European History. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226893778.