Pramipexole

Pramipexole, sold under the brand Mirapex among others, is medication used to treat Parkinson's disease (PD) and restless legs syndrome (RLS).[1] In PD it may be used alone or together with levodopa.[1] It is taken by mouth.[1]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌpræmɪˈpɛksoʊl/ |

| Trade names | Mirapex, Mirapexin, Sifrol, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a697029 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | >90% |

| Protein binding | 15% |

| Elimination half-life | 8–12 hours |

| Excretion | Urine (90%), Feces (2%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.124.761 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

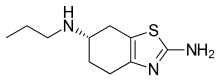

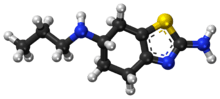

| Formula | C10H17N3S |

| Molar mass | 211.33 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Common side effects include nausea, headache, feeling tired, trouble sleeping, dry mouth, and hallucinations.[1] Serious side effects may include an urge to gamble or have sex, heart failure, and low blood pressure.[1] Use in pregnancy and breastfeeding is of unclear safety.[2] It is a dopamine agonist of the non-ergoline class.[1]

Pramipexole was approved for medical use in the United States in 1997.[1] It is available as a generic medication.[3] In 2017, it was the 179th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than three million prescriptions.[4][5]

Medical uses

Pramipexole is used in the treatment of Parkinson's disease (PD) and restless legs syndrome (RLS).[1]

Side effects

Common side effects of pramipexole may include:[6][7]

- Headache

- Peripheral edema[8]

- Hyperalgesia (body aches and pains)

- Nausea and vomiting

- Sedation and somnolence

- Decreased appetite and subsequent weight loss

- Orthostatic hypotension (resulting in dizziness, lightheadedness, and possibly fainting, especially when standing up)

- Insomnia

- Hallucinations (seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting or feeling things that are not there), amnesia and confusion

- Twitching, twisting, or other unusual body movements

- Unusual tiredness or weakness

Several unusual adverse effects of pramipexole (and related D3-preferring dopamine agonist medications such as ropinirole) may include compulsive gambling, punding, hypersexuality, and overeating, even in people without any prior history of these behaviours.[9][10][11] Pramipexole may cause paradoxical worsening of restless legs syndrome in some cases.[1] Use in pregnancy and breastfeeding is of unclear safety.[2]

Pharmacology

Pramipexole acts as a partial/full agonist at the following receptors:[12][13]

- D2S receptor (Ki = 3.9 nM; IA = 130%)

- D2L receptor (Ki = 2.2 nM; IA = 70%)

- D3 receptor (Ki = 0.5 nM; IA = 70%)

- D4 receptor (Ki = 5.1 nM; IA = 42%)

Pramipexole also possesses low/insignificant affinity (500–10,000 nM) for the 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, 5-HT1D, and α2-adrenergic receptors.[12][14] It has negligible affinity (>10,000 nM) for the D1, D5, 5-HT2, α1-adrenergic, β-adrenergic, H1, and mACh receptors.[12][14] All sites assayed were done using human tissues.[12][13]

While pramipexole is used clinically (see below), its D3-preferring receptor binding profile has made it a popular tool compound for preclinical research. For example, pramipexole has been used (in combination with D2- and or D3-preferring antagonists) to discover the role of D3 receptor function in rodent models and tasks for neuropsychiatric disorders.[15] Of note, it appears that pramipexole, in addition to having effects on dopamine D3 receptors, may also affect mitochondrial function via a mechanism that remains less understood. A pharmacological approach to separate dopaminergic from non-dopaminergic (e.g. mitochondrial) effects of pramipexole has been to study the effects of the R-stereoisomer of pramipexole (which has much lower affinity to the dopamine receptors when compared to the S-isomer) side by side with the effects of the S-isomer.[16]

Parkinson's disease is a neurodegenerative disease affecting the substantia nigra, a component of the basal ganglia. The substantia nigra has a high quantity of dopaminergic neurons, which are nerve cells that release the neurotransmitter known as dopamine. When dopamine is released, it may activate dopamine receptors in the striatum, which is another component of the basal ganglia. When neurons of the substantia nigra deteriorate in Parkinson's disease, the striatum no longer properly receives dopamine signals. As a result, the basal ganglia can no longer regulate body movement effectively and motor function becomes impaired. By acting as an agonist for the D2, D3, and D4 dopamine receptors, pramipexole may directly stimulate the underfunctioning dopamine receptors in the striatum, thereby restoring the dopamine signals needed for proper functioning of the basal ganglia.

Brand names

Brand names include Mirapex, Mirapexin, Sifrol, Glepark, and Oprymea.

Research

Pramipexole has been evaluated for the treatment of sexual dysfunction experienced by some users of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants.[17] Pramipexole has shown effects on pilot studies in a placebo-controlled proof of concept study in bipolar disorder.[18][19][20] It is also being investigated for the treatment of clinical depression and fibromyalgia.[21][22][23]

References

- "Pramipexole Dihydrochloride Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- "Pramipexole Pregnancy and Breastfeeding Warnings". Drugs.com. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- British national formulary : BNF 76 (76 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. pp. 417–418. ISBN 9780857113382.

- "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "Pramipexole Dihydrochloride - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "MedlinePlus Drug Information: Pramipexole (Systemic)". United States National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2006-09-26. Retrieved 2006-09-27.

- "FDA Prescribing Information: Mirapex (pramipexole dihydrochloride)" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration (United States). Retrieved 2008-12-31.

- Tan EK, Ondo W (2000). "Clinical characteristics of pramipexole-induced peripheral edema". Arch Neurol. 57 (5): 729–732. doi:10.1001/archneur.57.5.729. PMID 10815140.

- Bostwick JM, Hecksel KA, Stevens SR, Bower JH, Ahlskog JE (April 2009). "Frequency of new-onset pathologic compulsive gambling or hypersexuality after drug treatment of idiopathic Parkinson disease". Mayo Clin. Proc. 84 (4): 310–6. doi:10.4065/84.4.310. PMC 2665974. PMID 19339647.

- Moore TJ; Glenmullen J; Mattison DR (December 2014). "Reports of Pathological Gambling, Hypersexuality, and Compulsive Shopping Associated With Dopamine Receptor Agonist Drugs". JAMA Internal Med. 174 (12): 1930–1933. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5262. PMID 25329919.

- Wolters ECh; van der Werf YD; van den Heuvel OA (September 2008). "Parkinson's disease-related disorders in the impulsive-compulsive spectrum". J. Neurol. 255 Suppl 5: 48–56. doi:10.1007/s00415-008-5010-5. PMID 18787882.

- Kvernmo T, Härtter S, Burger E (August 2006). "A review of the receptor-binding and pharmacokinetic properties of dopamine agonists". Clinical Therapeutics. 28 (8): 1065–78. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.08.004. PMID 16982285.

- Newman-Tancredi A, Cussac D, Audinot V, et al. (November 2002). "Differential actions of antiparkinson agents at multiple classes of monoaminergic receptor. II. Agonist and antagonist properties at subtypes of dopamine D(2)-like receptor and alpha(1)/alpha(2)-adrenoceptor". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 303 (2): 805–14. doi:10.1124/jpet.102.039875. PMID 12388667.

- Millan MJ, Maiofiss L, Cussac D, Audinot V, Boutin JA, Newman-Tancredi A (November 2002). "Differential actions of antiparkinson agents at multiple classes of monoaminergic receptor. I. A multivariate analysis of the binding profiles of 14 drugs at 21 native and cloned human receptor subtypes". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 303 (2): 791–804. doi:10.1124/jpet.102.039867. PMID 12388666.

- Weber, M; Chang W; Breier M; Ko D; Swerdlow NR (December 2008). "Heritable strain differences in sensitivity to the startle gating-disruptive effects of D2 but not D3 receptor stimulation". Behav Pharmacol. 19 (8): 786–795. doi:10.1097/FBP.0b013e32831c3b2b. PMC 3255557. PMID 19020413.

- Chang, W; Weber M; Breier MR; Saint Marie RL; Hines SR; Swerdlow NR (February 2012). "Stereochemical and neuroanatomical selectivity of pramipexole effects on sensorimotor gating in rats". Brain Res. 1437: 69–76. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2011.12.007. PMC 3268831. PMID 22227455.

- DeBattista C, Solvason HB, Breen JA, Schatzberg AF (2000). "Pramipexole augmentation of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor in the treatment of depression". J Clin Psychopharmacol. 20 (2): 274–275. doi:10.1097/00004714-200004000-00029. PMID 10770475.

- Zarate CA, Payne JL, Singh J, et al. (July 2004). "Pramipexole for bipolar II depression: a placebo-controlled proof of concept study". Biol. Psychiatry. 56 (1): 54–60. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.03.013. PMID 15219473.

- Goldberg JF, Burdick KE, Endick CJ (March 2004). "Preliminary, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of pramipexole added to mood stabilizers for treatment resistant bipolar depression". American Journal of Psychiatry. 161 (3): 161:564–566. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.564. PMID 14992985.

- Guy M. Goodwina; A. Martinez-Aranb; David C. Glahn c; Eduard Vieta b (November 2008). "Cognitive impairment in bipolar disorder: Neurodevelopment or neurodegeneration? An ECNP expert meeting report". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 18 (11): 787–793. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2008.07.005. PMID 18725178.

- Lattanzi L, Dell'Osso L, Cassano P, Pini S, Rucci P, Houck PR, Gemignani A, Battistini G, Bassi A, Abelli M, Cassano GB (2002). "Pramipexole in treatment-resistant depression: a 16-week naturalistic study". Bipolar Disord. 4 (5): 307–314. doi:10.1034/j.1399-5618.2002.01171.x. PMID 12479663.

- Cassano P, Lattanzi L, Soldani F, Navari S, Battistini G, Gemignani A, Cassano GB (2004). "Pramipexole in treatment-resistant depression: an extended follow-up". Depression and Anxiety. 20 (3): 131–138. doi:10.1002/da.20038. PMID 15549689.

- Holman AJ, Myers RR (2005). "A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of pramipexole, a dopamine agonist, in patients with fibromyalgia receiving concomitant medications". Arthritis Rheum. 52 (8): 2495–2505. doi:10.1002/art.21191. PMID 16052595.