Chongqing

Chongqing (Sichuanese pronunciation: [tsʰoŋ˨˩tɕʰin˨˩˦], Standard Mandarin pronunciation: [ʈʂʰʊ̌ŋ.tɕʰîŋ] (![]()

Chongqing 重庆市 Chungking, Ch'ung-ch'ing | |

|---|---|

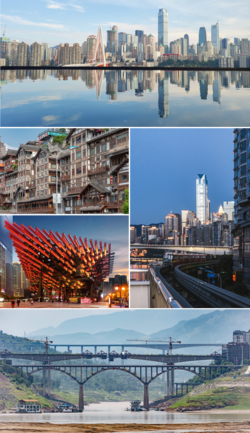

Clockwise from top: Yuzhong District skyline, Chongqing Rail Transit Line 2 running along Jialing River, bridges under construction in Fengdu County, Chongqing Art Museum, and Hongya Cave | |

| |

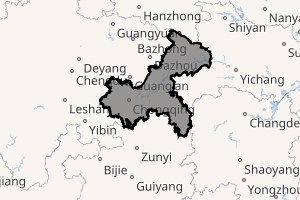

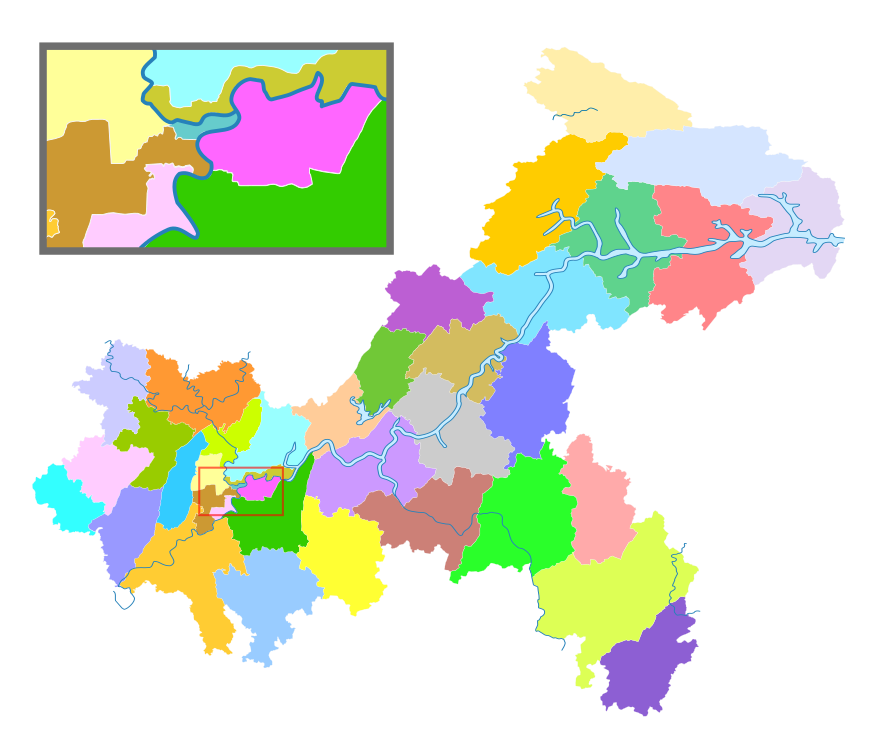

.svg.png) Location of Chongqing Municipality within China | |

| Coordinates (Chongqing municipal government): 29°33′49″N 106°33′01″E | |

| Country | People's Republic of China |

| Settled | c. 316 BC |

| Municipal seat | Yuzhong District |

| Divisions - County-level - Township-level | 25 districts, 13 counties 1259 towns, townships, and subdistricts |

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipality |

| • CPC Secretary | Chen Min'er |

| • Mayor | Tang Liangzhi |

| • Congress chairman | Zhang Xuan |

| • Conference chairman | Wang Jiong |

| Area | |

| • Municipality | 82,403 km2 (31,816 sq mi) |

| • Core districts | 5,472.8 km2 (2,113.1 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 244 m (801 ft) |

| Highest elevation | 1,709.4 m (5,608.3 ft) |

| Population (2016)[2] | |

| • Municipality | 30,484,300 |

| • Density | 370/km2 (960/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 18,384,100[note 1][3] |

| • Core districts | 8,518,000[4] |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (CST) |

| Postal code | 4000 00 – 4099 00 |

| Area code(s) | 23 |

| ISO 3166 code | CN-CQ |

| GDP | 2019[5] |

| - Total | CNY 2.36 trillion US$ 342 billion $675 billion (PPP) (17th) |

| - Per capita | CNY 75,828 US$ 10,992 $21,684 (PPP) (9th) |

| HDI (2018) | 0.759[6] (13th) – high |

| Licence plate prefixes | 渝A, 渝D (Yuzhong, Jiangbei, Jiulongpo, Dadukou) 渝B (Nan'an, Shapingba, Beibei, Wansheng, Shuangqiao, Yubei, Banan, Changshou) 渝C (Yongchuan, Hechuan, Jiangjin, Qijiang, Tongnan, Tongliang, Dazu, Rongchang, Bishan) 渝F (Wanzhou, Liangping, Chengkou, Wushan, Wuxi, Zhongxian, Kaizhou, Fengjie, Yunyang) 渝G (Fuling, Nanchuan, Dianjiang, Fengdu, Wulong) 渝H (Qianjiang, Shizhu, Xiushan, Youyang, Pengshui) |

| Abbreviation | CQ / 渝; Yú |

| City flower | Camellia[7] |

| City tree | Ficus lacor[8] |

| Website | CQ.gov.cn (in Chinese) English.CQ.gov.cn |

| Chongqing | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.svg.png) "Chongqing" in Simplified (top) and Traditional (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 重庆 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 重慶 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cong2qin4 (Sichuanese Pinyin) [tsʰoŋ˨˩ tɕʰin˨˩˦] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Postal | Chungking | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Doubled Celebration" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Chongqing was a municipality during the Republic of China (ROC) administration, within the Sichuan Province. It served as its wartime capital during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945), being one of the world's anti-fascist command centers. The current municipality was separated from Sichuan province on 14 March 1997 to help develop the central and western parts of China.[13] The Chongqing administrative municipality has a population of over 30 million.[14] The city of Chongqing, comprising 9 urban and suburban districts, has a population of 8,518,000 as of 2016.[4] According to the 2010 census, Chongqing is the most populous Chinese municipality,[15] and also the largest direct-controlled municipality in China, containing 26 districts, eight counties, and four autonomous counties.

The official abbreviation of the city, "Yú" (渝), was approved by the State Council on 18 April 1997.[16] This abbreviation is derived from the old name of a part of the Jialing River that runs through Chongqing and feeds into the Yangtze River.

Chongqing has a significant history and culture. Being one of China's National Central Cities, it serves as the economic centre of the Sichuan Basin and the upstream Yangtze. It is a major manufacturing centre and transportation hub; a July 2012 report by the Economist Intelligence Unit described it as one of China's "13 emerging megalopolises".[17]

History

Ancient history

Tradition associates Chongqing with the State of Ba. This new capital was first named Jiangzhou (江州).[18]

Imperial era

Jiangzhou subsequently remained under Qin Shi Huang's rule during the Qin dynasty, the successor of the Qin State, and under the control of Han dynasty emperors. Jiangzhou was subsequently renamed during the Northern and Southern dynasties to Chu Prefecture (楚州), then in 581 AD (Sui dynasty) to Yu Prefecture (渝州), and later in 1102 during Northern Song to Gong Prefecture (恭州).[19] The name Yu however survives to this day as an abbreviation for Chongqing, and the city centre where the old town stood is also called Yuzhong (渝中, Central Yu).[18] It received its current name in 1189, after Prince Zhao Dun of the Southern Song dynasty described his crowning as king and then Emperor Guangzong as a "double celebration" (simplified Chinese: 双重喜庆; traditional Chinese: 雙重喜慶; pinyin: shuāngchóng xǐqìng, or chongqing in short). In his honour, Yu Prefecture was therefore converted to Chongqing Fu, marking the occasion of his enthronement.

In 1362, (Yuan dynasty), Ming Yuzhen, a peasant rebel leader, established the Daxia Kingdom (大夏) at Chongqing for a short time.[20] In 1621 (Ming dynasty), another short-lived kingdom of Daliang (大梁) was established by She Chongming (奢崇明) with Chongqing as its capital.[21] In 1644, after the fall of the Ming dynasty to a rebel army, Chongqing, together with the rest of Sichuan, was captured by Zhang Xianzhong, who was said to have massacred a large number of people in Sichuan and depopulated the province, in part by causing many people to flee to safety elsewhere. The Manchus later conquered the province, and during the Qing dynasty, immigration to Chongqing and Sichuan took place with the support of the Qing emperor.[22]

In 1890, the British Consulate General was opened in Chongqing.[23] The following year, the city became the first inland commerce port open to foreigners.[24] The French, German, US and Japanese consulates were opened in Chongqing in 1896–1904.[25][26][27][28]

Provisional capital of the Republic of China

During and after the Second Sino-Japanese War, from Nov 1937 to May 1946, it was Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek's provisional capital. Indeed, after the General and remaining army had lived there for a time following their retreat in 1938 from the previous capital of Wuhan, it was formally declared the second capital city (pei du) on 6 September 1940.[29] After Britain, the United States, and other Allies entered the war in Asia in December 1941, one of the Allies' deputy commanders of operations in South East Asia (South East Asia Command SEAC), Joseph Stilwell, was based in the city. This made it a city of world importance in the fight against Axis powers, together with London, Moscow and Washington, D.C.[30] The city was also visited by Lord Louis Mountbatten, the Supreme Commander of SEAC which was itself headquartered in Ceylon, modern day Sri Lanka. Chiang Kai Shek as Supreme Commander in China worked closely with Stilwell.[31] From 1938 to 1943, the city suffered from continuous terror bombing by the Japanese air force. Lives were saved by the air-raid shelters which took the advantage of the mountainous terrain. Chongqing was acclaimed to be the “City of Heroes” due to the indomitable spirits of its people as well as their contributions and sacrifices during World War II. Many factories and universities were relocated from eastern China to Chongqing during the war, transforming this city from inland port to a heavily industrialized city. In late November 1949, the Nationalist KMT government retreated from the city.[32]

Municipality status

On 14 March 1997, the Eighth National People's Congress decided to merge the Sub-provincial city with the neighbouring Fuling, Wanxian, and Qianjiang prefectures that it had governed on behalf of the province since September 1996. The resulting single division became Chongqing Municipality, containing 30,020,000 people in forty-three former counties (without intermediate political levels). The municipality became the spearhead of China's effort to develop its western regions and to coordinate the resettlement of residents from the reservoir areas of the Three Gorges Dam project. Its first official ceremony took place on 18 June 1997. On 8 February 2010, Chongqing became one of the four National Central/Core cities, the other three are Beijing, Shanghai and Tianjin.[33] On 18 June 2010, Liangjiang New Area was established in Chongqing, which is the third State-level new areas at the time of its establishment.[34]

Geography

Physical geography and topography

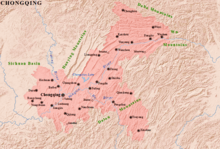

Chongqing is situated at the transitional area between the Tibetan Plateau and the plain on the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River in the sub-tropical climate zone often swept by moist monsoons. It often rains at night in late spring and early summer, and thus the city is famous for its "night rain in the Ba Mountains", as described by poems throughout Chinese history including the famous Written on a Rainy Night-A Letter to the North by Li Shangyin.[35] The municipality reaches a maximum width of 470 kilometres (290 mi) from east to west, and a maximum length of 450 km (280 mi) from north to south.[36] It borders the following provinces: Hubei in the east, Hunan in the southeast, Guizhou in the south, Sichuan in the west and northwest, and Shaanxi to the north in its northeast corner.[37]

Chongqing covers a large area crisscrossed by rivers and mountains. The Daba Mountains stand in the north, the Wu Mountains in the east, the Wuling Mountains in the southeast, and the Dalou Mountains in the south. The whole area slopes down from north and south towards the Yangtze River valley, with sharp rises and falls. The area is featured by a large geological massif, of mountains and hills, with large sloping areas at different heights.[38] Typical karst landscape is common in this area, and stone forests, numerous collections of peaks, limestone caves and valleys can be found in many places. The Longshuixia Gap (龙水峡地缝), with its natural arch-bridges, has made the region a popular tourist attraction. The Yangtze River runs through the whole area from west to east, covering a course of 665 km (413 mi), cutting through the Wu Mountains at three places and forming the well-known Three Gorges: the Qutang, the Wuxia and the Xiling gorges.[39] Coming from northwest and running through "the Jialing Lesser Three Gorges" of Libi, Wentang and Guanyin, the Jialing River joins the Yangtze in Chongqing.[40]

I've sailed a thousand li through canyons in a day.

With the monkeys' adieus the riverbanks are loud,

The central urban area of Chongqing, or Chongqing proper, is a city of unique features. Built on mountains and partially surrounded by the Yangtze and Jialing rivers, it is known as a "mountain city" and a "city on rivers".[41] The night scene of the city is very illuminated, with millions of lights and their reflection on the rivers. With its special topographical features, Chongqing has the unique scenery of mountains, rivers, forests, springs, waterfalls, gorges, and caves. Li Bai, a famous poet of the Tang dynasty, was inspired by the natural scenery and wrote this epigram.[42]

Specifically, the central urban area is located on a huge folding area. Yuzhong District, Nan'an District, Shapingba District and Jiangbei District are located right on a big syncline. And the "Southern Mountain of Chongqing" (Tongluo Mountain), along with the Zhongliang Mountain are two anticlines next to the syncline of downtown.[43]

Zhongliang Mountains (中梁山) and Tongluo Mountains (铜锣山) roughly forms the eastern and western boundaries of Chongqing's urban area. The highest point in downtown is the top of Eling Hill, which is a smaller syncline hill that keeps Yangtze River and Jialing River apart for some more kilometres. The elevation of Eling Hill is 379 metres (1,243 feet). The lowest point is Chaotian Gate, where the two rivers merge with each other. The altitude there is 160 metres (520 feet). The average height of the area is 259 metres (850 feet). However, there are several high mountains outside central Chongqing, such as the Wugong Ling Mountain, with the altitude of 1,709.4 metres (5,608 feet), in Jiangjin.

Climate

Chongqing has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa), bordering on a monsoonal humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cwa) and for most of the year experiences very high relative humidity, with all months above 75%. Known as one of the "Three Furnaces" of the Yangtze river, along with Wuhan and Nanjing, its summers are long and among the hottest and most humid in China, with highs of 33 to 34 °C (91 to 93 °F) in July and August in the urban area.[44] Winters are short and somewhat mild, but damp and overcast. The city's location in the Sichuan Basin causes it to have one of the lowest annual sunshine totals nationally, at only 1,055 hours, lower than much of Northern Europe; the monthly percent possible sunshine in the city proper ranges from a mere 8% in December and January to 48% in August. Extremes since 1951 have ranged from −1.8 °C (29 °F) on 15 December 1975 (unofficial record of −2.5 °C (27 °F) was set on 8 February 1943) to 43.0 °C (109 °F) on 15 August 2006 (unofficial record of 44.0 °C (111 °F) was set on 8 and 9 August 1933).[45]

Chongqing, with over 100 days of fog per year,[46] is known as the "Fog City" (雾都), like San Francisco, and a thick layer of fog enshrouds it for 68 days per year during the spring and autumn.[47][48] During the Second Sino-Japanese War, this special weather possibly played a role in protecting the city from being overrun by the Imperial Japanese Army.

As exemplified by Youyang County below, conditions are often cooler in the southeast part of the municipality due to the higher elevations there.

| Climate data for Chongqing (Shapingba District, 1981–2010 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 18.8 (65.8) |

24.6 (76.3) |

34.0 (93.2) |

36.5 (97.7) |

38.9 (102.0) |

39.8 (103.6) |

42.0 (107.6) |

43.0 (109.4) |

41.9 (107.4) |

35.1 (95.2) |

29.2 (84.6) |

21.5 (70.7) |

43.0 (109.4) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 10.3 (50.5) |

12.9 (55.2) |

17.7 (63.9) |

23.0 (73.4) |

27.2 (81.0) |

29.4 (84.9) |

33.0 (91.4) |

33.2 (91.8) |

28.3 (82.9) |

21.7 (71.1) |

17.1 (62.8) |

11.5 (52.7) |

22.1 (71.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 7.9 (46.2) |

10.0 (50.0) |

13.8 (56.8) |

18.6 (65.5) |

22.6 (72.7) |

25.1 (77.2) |

28.3 (82.9) |

28.3 (82.9) |

24.1 (75.4) |

18.6 (65.5) |

14.2 (57.6) |

9.2 (48.6) |

18.4 (65.1) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 6.2 (43.2) |

8.0 (46.4) |

11.2 (52.2) |

15.4 (59.7) |

19.3 (66.7) |

22.1 (71.8) |

24.8 (76.6) |

24.7 (76.5) |

21.2 (70.2) |

16.5 (61.7) |

12.3 (54.1) |

7.7 (45.9) |

15.8 (60.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −1.8 (28.8) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

1.2 (34.2) |

2.8 (37.0) |

10.8 (51.4) |

15.5 (59.9) |

19.2 (66.6) |

17.8 (64.0) |

14.3 (57.7) |

6.9 (44.4) |

0.7 (33.3) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 19.7 (0.78) |

23.3 (0.92) |

43.2 (1.70) |

95.2 (3.75) |

145.9 (5.74) |

192.6 (7.58) |

186.0 (7.32) |

137.9 (5.43) |

105.8 (4.17) |

85.8 (3.38) |

48.3 (1.90) |

24.3 (0.96) |

1,108 (43.63) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 10.0 | 9.8 | 11.9 | 14.3 | 15.5 | 15.7 | 12.5 | 11.3 | 12.7 | 16.1 | 11.5 | 9.8 | 151.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 84 | 80 | 77 | 77 | 77 | 81 | 76 | 74 | 79 | 85 | 84 | 85 | 80 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 20.6 | 29.7 | 64.9 | 93.6 | 109.4 | 97.7 | 158.6 | 167.0 | 106.6 | 50.4 | 35.9 | 20.4 | 954.8 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 8 | 11 | 18 | 25 | 26 | 26 | 42 | 48 | 28 | 18 | 13 | 8 | 24 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 10 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 8 |

| Source 1: China Meteorological Administration[49][50] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas (uv)[51] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Youyang Tujia and Miao Autonomous County (1971–2000) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 7.5 (45.5) |

8.8 (47.8) |

13.0 (55.4) |

19.7 (67.5) |

23.9 (75.0) |

26.9 (80.4) |

30.0 (86.0) |

30.2 (86.4) |

25.6 (78.1) |

20.3 (68.5) |

15.1 (59.2) |

10.3 (50.5) |

19.3 (66.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 1.5 (34.7) |

2.8 (37.0) |

6.3 (43.3) |

11.5 (52.7) |

15.6 (60.1) |

19.2 (66.6) |

21.5 (70.7) |

21.1 (70.0) |

17.5 (63.5) |

12.8 (55.0) |

8.0 (46.4) |

3.4 (38.1) |

11.8 (53.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 29.1 (1.15) |

31.6 (1.24) |

56.7 (2.23) |

128.5 (5.06) |

195.1 (7.68) |

242.3 (9.54) |

178.1 (7.01) |

145.0 (5.71) |

122.5 (4.82) |

109.5 (4.31) |

67.9 (2.67) |

25.4 (1.00) |

1,331.7 (52.42) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 12.0 | 12.2 | 15.9 | 16.9 | 18.1 | 17.1 | 15.4 | 14.4 | 13.0 | 15.1 | 11.6 | 9.7 | 171.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 77 | 77 | 79 | 80 | 81 | 83 | 82 | 81 | 81 | 82 | 79 | 76 | 80 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 42.5 | 37.4 | 47.6 | 83.3 | 102.7 | 101.4 | 155.9 | 171.7 | 112.3 | 88.7 | 68.7 | 64.4 | 1,076.6 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 13 | 12 | 13 | 22 | 25 | 24 | 37 | 42 | 31 | 25 | 21 | 20 | 24.3 |

| Source: China Meteorological Administration | |||||||||||||

Cityscape

Politics

Chongqing has been, since 1997, a direct-controlled municipality in the Chinese administrative structure, making it a provincial-level division with commensurate political importance. The municipality's top leader is the secretary of the municipal committee of the Communist Party of China ("party chief"), which, since 2007, has also held a seat on the Politburo of the Communist Party of China, the country's second highest governing council. Under the Soviet-inspired nomenklatura system of appointments, individuals are appointed to the position by the central leadership of the Communist Party, and bestowed to an official based on seniority and adherence to party orthodoxy, usually given to an individual with prior regional experience elsewhere in China and nearly never a native of Chongqing. Notable individuals who have held the municipal Party Secretary position include He Guoqiang, Wang Yang, Bo Xilai, Zhang Dejiang, and Sun Zhengcai, the latter three were Politburo members during their term as party chief. The party chief heads the municipal party standing committee, the de facto top governing council of the municipality. The standing committee is typically composed of 13 individuals which includes the party chiefs of important subdivisions and other leading figures in the local party and government organization, as well as one military representative.

The municipal People's Government serves as the day-to-day administrative authority, and is headed by the mayor, who is assisted by numerous vice mayors and mayoral assistants. Each vice mayor is given jurisdiction over specific municipal departments. The mayor is the second-highest-ranking official in the municipality. The mayor usually represents the city when foreign guests visit.[52]

The municipality also has a People's Congress, theoretically elected by lower level People's Congresses. The People's Congress nominally appoints the mayor and approves the nominations of other government officials. The People's Congress, like those of other provincial jurisdictions, is generally seen as a symbolic body. It convenes in full once a year to approve party-sponsored resolutions and local regulations and duly confirm party-approved appointments. On occasion the People's Congress can be venues of discussion on municipal issues, although this is dependent on the actions of individual delegates. The municipal People's Congress is headed by a former municipal official, usually in their late fifties or sixties, with a lengthy prior political career in Chongqing. The municipal Political Consultative Conference (zhengxie) meets at around the same time as the People's Congress. Its role is to advise on political issues. The zhengxie is headed by a leader who is typically a former municipal or regional official with a lengthy career in the party and government bureaucracy.

Military

Chongqing was the wartime capital of China during the Second Sino-Japanese war (i.e., World War II), and from 1938 to 1946,[53] the seat of administration for the Republic of China's government before its departure to Nanjing and then Taiwan.[54] After the eventual defeat at the Battle of Wuhan General Chiang-Kai Shek and the army were forced to use it as base of resistance from 1938 onwards.[55] It also contains a military museum named after the Chinese Korean War hero Qiu Shaoyun.[56]

Chongqing used to be the headquarters of the 13th Group Army of the People's Liberation Army, one of the two group armies that formerly comprised the Chengdu Military Region, which in 2016 was re-organized into the Western Theater Command.[57]

Administrative divisions

Chongqing is the largest of the four direct-controlled municipalities of the People's Republic of China. The municipality is divided into 38 subdivisions (3 were abolished in 1997, and Wansheng and Shuangqiao districts were abolished in October 2011[58]), consisting of 26 districts, 8 counties, and 4 autonomous counties. The boundaries of Chongqing municipality reach much farther into the city's hinterland than the boundaries of the other three provincial level municipalities (Beijing, Shanghai and Tianjin), and much of its administrative area, which spans over 80,000 square kilometres (30,900 sq mi), is rural. At the end of year 2017, the total population is 30.75 million.

| Administrative divisions of Chongqing | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

| Division code[59] | Division | Area in km2[60] | Total population 2010[61] | Urban area population 2010[62] |

Seat | Postal code | Subdivisions[63] | |||||||

| Subdistricts | Towns | Townships [n 1] |

Ethnic townships | Residential communities | Villages | |||||||||

| 500000 | Chongqing | 82403 | 28,846,170 | 15295803 | Yuzhong | 400000 | 181 | 567 | 233 | 14 | 2324 | 5235 | ||

| 500101 | Wanzhou | 3457 | 1,563,050 | 859,662 | Chenjiaba Subdistrict | 404000 | 11 | 29 | 10 | 2 | 187 | 448 | ||

| 500102 | Fuling | 2946 | 1,066,714 | 595,224 | Lizhi Subdistrict | 408000 | 8 | 12 | 6 | 108 | 310 | |||

| 500103 | Yuzhong | 23 | 630,090 | Qixinggang Subdistrict | 400000 | 12 | 78 | |||||||

| 500104 | Dadukou | 102 | 301,042 | 280,512 | Xinshancun Subdistrict | 400000 | 5 | 2 | 48 | 32 | ||||

| 500105 | Jiangbei | 221 | 738,003 | 672,545 | Cuntan Subdistrict | 400000 | 9 | 3 | 88 | 48 | ||||

| 500106 | Shapingba | 396 | 1,000,013 | 900,568 | Qinjiagang Subdistrict | 400000 | 18 | 8 | 140 | 86 | ||||

| 500107 | Jiulongpo | 431 | 1,084,419 | 939,349 | Yangjiaping Subdistrict | 400000 | 7 | 11 | 107 | 105 | ||||

| 500108 | Nan'an | 263 | 759,570 | 683,717 | Tianwen Subdistrict | 400000 | 7 | 7 | 85 | 61 | ||||

| 500109 | Beibei | 754 | 680,360 | 501,822 | Beiwenquan Subdistrict | 400700 | 5 | 12 | 63 | 117 | ||||

| 500110 | Qijiang | 2747 | 1,056,817 | 513,935 | Gunan Subdistrict | 400800 | 5 | 25 | 99 | 365 | ||||

| 500111 | Dazu | 1433 | 721,359 | 315,183 | Tangxiang Subdistrict | 400900 | 3 | 24 | 103 | 197 | ||||

| 500112 | Yubei | 1452 | 1,345,410 | 985,918 | Shuangfengqiao Subdistrict | 401100 | 14 | 12 | 155 | 215 | ||||

| 500113 | Banan | 1834 | 918,692 | 669,269 | Longzhouwan Subdistrict | 401300 | 8 | 14 | 87 | 198 | ||||

| 500114 | Qianjiang | 2397 | 445,012 | 173,997 | Chengxi Subdistrict | 409700 | 6 | 12 | 12 | 80 | 138 | |||

| 500115 | Changshou | 1423 | 770,009 | 408,261 | Fengcheng Subdistrict | 401200 | 4 | 14 | 31 | 223 | ||||

| 500116 | Jiangjin | 3200 | 1,233,149 | 686,189 | Jijiang Subdistrict | 402200 | 4 | 24 | 85 | 180 | ||||

| 500117 | Hechuan | 2356 | 1,293,028 | 721,753 | Nanjin Street Subdistrict | 401500 | 7 | 23 | 61 | 327 | ||||

| 500118 | Yongchuan | 1576 | 1,024,708 | 582,769 | Zhongshan Road Subdistrict | 402100 | 7 | 16 | 52 | 208 | ||||

| 500119 | Nanchuan | 2602 | 534,329 | 255,045 | Dongcheng Subdistrict | 408400 | 3 | 15 | 15 | 58 | 185 | |||

| 500120 | Bishan | 912 | 586,034 | 246,425 | Bicheng Subdistrict | 402700 | 6 | 9 | 43 | 142 | ||||

| 500151 | Tongliang | 1342 | 600,086 | 248,962 | Bachuan Subdistrict | 402500 | 3 | 25 | 57 | 269 | ||||

| 500152 | Tongnan | 1585 | 639,985 | 247,084 | Guilin Subdistrict | 402600 | 2 | 20 | 21 | 281 | ||||

| 500153 | Rongchang | 1079 | 661,253 | 271,232 | Changyuan Subdistrict | 402400 | 6 | 15 | 75 | 92 | ||||

| 500154 | Kaizhou | 3959 | 1,160,336 | 416,415 | Hanfeng Subdistrict | 405400 | 7 | 26 | 7 | 78 | 435 | |||

| 500155 | Liangping | 1890 | 687,525 | 235,753 | Liangshan Subdistrict | 405200 | 2 | 26 | 7 | 33 | 310 | |||

| 500156 | Wulong | 2872 | 351,038 | 115,823 | Gangkou town | 408500 | 12 | 10 | 4 | 24 | 184 | |||

| 500229 | Chengkou Co. | 3286 | 192,967 | 49,039 | Gecheng Subdistrict | 405900 | 2 | 6 | 17 | 22 | 184 | |||

| 500230 | Fengdu Co. | 2896 | 649,182 | 224,003 | Sanhe Subdistrict | 408200 | 2 | 23 | 5 | 53 | 277 | |||

| 500231 | Dianjiang Co. | 1518 | 704,458 | 241,424 | Guixi Subdistrict | 408300 | 2 | 23 | 2 | 62 | 236 | |||

| 500233 | Zhong Co. | 2184 | 751,424 | 247,406 | Zhongzhou town | 404300 | 22 | 5 | 1 | 49 | 317 | |||

| 500235 | Yunyang Co. | 3634 | 912,912 | 293,636 | Shuangjiang Subdistrict | 404500 | 4 | 22 | 15 | 1 | 87 | 391 | ||

| 500236 | Fengjie Co. | 4087 | 834,259 | 269,302 | Yong'an town | 404600 | 19 | 8 | 4 | 54 | 332 | |||

| 500237 | Wushan Co. | 2958 | 495,072 | 148,597 | Gaotang Subdistrict | 404700 | 11 | 12 | 2 | 30 | 308 | |||

| 500238 | Wuxi Co. | 4030 | 414,073 | 105,111 | Baichang Subdistrict | 405800 | 2 | 15 | 16 | 38 | 292 | |||

| 500240 | Shizhu Co. | 3013 | 415,050 | 134,173 | Nanbin town | 409100 | 17 | 15 | 29 | 213 | ||||

| 500241 | Xiushan Co. | 2450 | 501,590 | 150,566 | Zhonghe Subdistrict | 409900 | 14 | 18 | 59 | 208 | ||||

| 500242 | Youyang Co. | 5173 | 578,058 | 137,635 | Taohuayuan town | 409800 | 15 | 23 | 8 | 270 | ||||

| 500243 | Pengshui Co. | 3903 | 545,094 | 137,409 | Hanjia Subdistrict | 409600 | 11 | 28 | 55 | 241 | ||||

| Divisions in Chinese and varieties of romanizations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | Chinese | Hanyu Pinyin | Sichuanese Pinyin | |

| Chongqing Municipality | 重庆市 | Chóngqìng Shì | cong2 qin4 si4 | |

| Wanzhou District | 万州区 | Wànzhōu Qū | wan4 zou2 qu1 | |

| Fuling District | 涪陵区 | Fúlíng Qū | ||

| Yuzhong District | 渝中区 | Yúzhōng Qū | yu2 zong1 qu1 | |

| Dadukou District | 大渡口区 | Dàdùkǒu Qū | da4 du4 kou3 qu1 | |

| Jiangbei District | 江北区 | Jiāngběi Qū | jiang1 be2 qu1 | |

| Shapingba District | 沙坪坝区 | Shāpíngbà Qū | sa1 pin2 ba4 qu1 | |

| Jiulongpo District | 九龙坡区 | Jiǔlóngpō Qū | ||

| Nan'an District | 南岸区 | Nán'àn Qū | lan2 ngan4 qu1 | |

| Beibei District | 北碚区 | Běibèi Qū | ||

| Qijiang District | 綦江区 | Qíjiāng Qū | ||

| Dazu District | 大足区 | Dàzú Qū | ||

| Yubei District | 渝北区 | Yúběi Qū | yu2 be2 qu1 | |

| Banan District | 巴南区 | Bānán Qū | ba1 lan2 qu1 | |

| Qianjiang District | 黔江区 | Qiánjiāng Qū | ||

| Changshou District | 长寿区 | Chángshòu Qū | ||

| Jiangjin District | 江津区 | Jiāngjīn Qū | jiang1 jin1 qu1 | |

| Hechuan District | 合川区 | Héchuān Qū | ho2 cuan1 qu1 | |

| Yongchuan District | 永川区 | Yǒngchuān Qū | yun3 cuan1 qu1 | |

| Nanchuan District | 南川区 | Nánchuān Qū | lan2 cuan1 qu1 | |

| Bishan District | 璧山区 | Bìshān Qū | ||

| Tongliang District | 铜梁区 | Tóngliáng Qū | ||

| Tongnan District | 潼南区 | Tóngnán Qū | ||

| Rongchang District | 荣昌区 | Róngchāng Qū | ||

| Kaizhou District | 开州区 | Kāizhōu Qū | kai1 zou1 qu1 | |

| Liangping District | 梁平区 | Liángpíng Qū | ||

| Wulong District | 武隆区 | Wǔlóng Qū | wu3 nong2 qu1 | |

| Chengkou County | 城口县 | Chéngkǒu Xiàn | cen2 kou3 xian3 | |

| Fengdu County | 丰都县 | Fēngdū Xiàn | ||

| Dianjiang County | 垫江县 | Diànjiāng Xiàn | ||

| Zhong County | 忠县 | Zhōngxiàn | zong1 xian3 | |

| Yunyang County | 云阳县 | Yúnyáng Xiàn | yun2 yang2 xian3 | |

| Fengjie County | 奉节县 | Fèngjié Xiàn | ||

| Wushan County | 巫山县 | Wūshān Xiàn | ||

| Wuxi County | 巫溪县 | Wūxī Xiàn | ||

| Shizhu Tujia Autonomous County | 石柱土家族自治县 | Shízhù Tǔjiāzú Zìzhìxiàn | ||

| Xiushan Tujia and Miao Autonomous County | 秀山土家族苗族自治县 | Xiùshān Tǔjiāzú Miáozú Zìzhìxiàn | ||

| Youyang Tujia and Miao Autonomous County | 酉阳土家族苗族自治县 | Yǒuyáng Tǔjiāzú Miáozú Zìzhìxiàn | ||

| Pengshui Miao and Tujia Autonomous County | 彭水苗族土家族自治县 | Péngshuǐ Miáozú Tǔjiāzú Zìzhìxiàn | ||

- Including other township related subdivisions.

Urban areas

| Population by urban areas of districts | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | City | Urban area[62] | District area[62] | Census date | |

| 1 | Chongqing[lower-roman 1] | 6,263,790 | 7,457,599 | 2010-11-01 | |

| 2 | Wanzhou | 859,662 | 1,563,050 | 2010-11-01 | |

| 3 | Hechuan | 721,753 | 1,293,028 | 2010-11-01 | |

| 4 | Jiangjin | 686,189 | 1,233,149 | 2010-11-01 | |

| 5 | Fuling | 595,224 | 1,066,714 | 2010-11-01 | |

| 6 | Yongchuan | 582,769 | 1,024,708 | 2010-11-01 | |

| 7 | Qijiang[lower-roman 2] | 513,935 | 1,056,817 | 2010-11-01 | |

| (8) | Kaizhou[lower-roman 3] | 416,415 | 1,160,336 | 2010-11-01 | |

| 9 | Changshou | 408,261 | 770,009 | 2010-11-01 | |

| 10 | Dazu[lower-roman 4] | 315,183 | 721,359 | 2010-11-01 | |

| (11) | Rongchang[lower-roman 5] | 271,232 | 661,253 | 2010-11-01 | |

| 12 | Nanchuan | 255,045 | 534,329 | 2010-11-01 | |

| (13) | Tongliang[lower-roman 6] | 248,962 | 600,086 | 2010-11-01 | |

| (14) | Tongnan[lower-roman 7] | 247,084 | 639,985 | 2010-11-01 | |

| (15) | Bishan[lower-roman 8] | 246,425 | 586,034 | 2010-11-01 | |

| (16) | Liangping[lower-roman 9] | 235,753 | 687,525 | 2010-11-01 | |

| 17 | Qianjiang | 173,997 | 445,012 | 2010-11-01 | |

| (18) | Wulong[lower-roman 10] | 115,823 | 351,038 | 2010-11-01 | |

- Chongqing core districts are consist of nine districts: Yuzhong, Dadukou, Jiangbei, Shapingba, Jiulongpo, Nan'an, Beibei, Yubei, & Banan.

- Wansheng & Qijiang County currently known as Qijiang after census.

- Kaizhou County is currently known as Kaizhou after census.

- Shuangqiao & Dazu County currently known as Dazu after census.

- Rongchang County is currently known as Rongchang after census.

- Tongliang County is currently known as Tongliang after census.

- Tongnan County is currently known as Tongnan after census.

- Bishan County is currently known as Bishan after census.

- Liangping County is currently known as Liangping after census.

- Wulong County is currently known as Wulong after census.

|

|

|

a Indicates with which district the division was associated below prior to the merging of Chongqing, Fuling, Wanxian (now Wanzhou) and Qianjiang in 1997.

Central Chongqing

The main urban area of Chongqing city (重庆主城区) spans approximately 5,473 square kilometres (2,113 square miles), and includes the following nine districts:[64][65]

- Yuzhong District (渝中区, or "Central Chongqing District"), the central and most densely populated district, where government and international business offices and the city's best shopping are located in the district's Jeifangbei CBD area. Yuzhong is located on the peninsula surrounded by Eling Hill, Yangtze River and Jialing River.

- Jiangbei District (江北区, or "River North District"), located to the north of Jialing River.

- Shapingba District (沙坪坝区), roughly located between Jialing River and Zhongliang Mountain.

- Jiulongpo District (九龙坡区), roughly located between Yangtze River and Zhongliang Mountain.

- Nan'an District (南岸区, or "Southern Bank District"), located on the south side of Yangtze River.

- Dadukou District (大渡口区)

- Banan District (巴南区, or "Southern Chongqing District"). Previously called Ba County, and changed to the current name in 1994. Its northern area merged into Chongqing, and its capital town Yudong is a satellite city of Chongqing.

- Yubei District (渝北区, or "Northern Chongqing District"). Previously called Jiangbei County, and changed into the current name in 1994. Its southern area merged into Chongqing, and the capital town Lianglu Town is a satellite city of Chongqing.

- Beibei District (北碚区), a satellite city northwest of Chongqing.

Demographics

Population

.jpg)

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1949 | 1,003,000 | — |

| 1979 | 6,301,000 | +528.2% |

| 1983 | 13,890,000 | +120.4% |

| 1996 | 15,297,000 | +10.1% |

| 1997[66]* | 28,753,000 | +88.0% |

| 2000[66] | 28,488,200 | −0.9% |

| 2005[66] | 27,980,000 | −1.8% |

| 2008[66] | 28,390,000 | +1.5% |

| 2012[66] | 28,846,170 | +1.6% |

| 2013[66] | 29,700,000 | +3.0% |

| 2014[67] | 29,914,000 | +0.7% |

| 2015[68] | 30,170,000 | +0.9% |

| *Population size in 1997 was affected by expansion of administrative divisions. | ||

According to a July 2010 article from the official Xinhua news agency, the municipality has a population of 32.8 million, including 23.3 million farmers. Among them, 8.4 million farmers have become migrant workers, including 3.9 million working and living in urban areas of Chongqing.[69] The metropolitan area encompassing the central urban area was estimated by the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) to have, as of 2010, a population of 17 million.[70][71]

This would mean that the locally registered farmers who work in other jurisdictions number 4.5 million, reducing the local, year-round population of Chongqing in 2010 to 28.3 million, plus those who are registered in other jurisdictions but live and work in Chongqing. According to China's 2005 statistical yearbook, of a total population of 30.55 million, those with residence registered in other jurisdictions but residing in the Chongqing enumeration area numbered 1.4 million, including 46,000 who resided in Chongqing "for less than half-year". An additional 83,000 had registered in Chongqing, but not yet settled there.[72]

The 2005 statistical yearbook also lists 15.22 million (49.82%) males and 15.33 million (50.18%) females.[72]

In terms of age distribution in 2004, of the 30.55 million total population, 6.4 million (20.88%) were age 0–14, 20.7 million (67.69%) were 15–64, and 3.5 million (11.46%) were 65 and over.[73]

Of a total 10,470,000 households (2004), 1,360,000 consisted of one person, 2,940,000 two-person, 3,190,000 three-person, 1,790,000 four-person, 783,000 five-person, 270,000 six-person, 89,000 seven-person, 28,000 eight-person, 6,000 nine-person, and 10,000 households of 10 or more persons per household.[74]

Religion

The predominant religions in Chongqing are Chinese folk religions, Taoist traditions and Chinese Buddhism. According to surveys conducted in 2007 and 2009, 26.63% of the population believes and is involved in cults of ancestors, while 1.05% of the population identifies as Christian.[75]

The reports didn't give figures for other types of religion; 72.32% of the population may be either irreligious or involved in worship of nature deities, Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism, folk religious sects.

Crime

In the first decade of the 21st century, the city became notorious for organised crime and corruption. Gangsters oversaw businesses involving billions of yuan and the corruption reached into the law-enforcement and justice systems. In 2009, city authorities under the auspices of municipal Communist Party secretary Bo Xilai undertook a large-scale crackdown, arresting 4,893 suspected gangsters, "outlaws" and corrupt cadres, leading to optimism that the period of gangsterism was over.[76] However, local media later highlighted the apparent reliance by the authorities on torture to extract confessions upon which convictions were based. In December 2009, one defence lawyer was controversially arrested and sentenced to 18 months in prison for "coaching his client to make false claims of torture" and in July 2010, another lawyer released videotapes of his client describing the torture in detail.[77] In 2014, four policemen involved in the interrogation were charged with the practice of "opposed illegal interrogation techniques", considered by observers to be torture.[78]

Economy

Chongqing was separated from Sichuan province and made into a municipality in its own right in 14 March 1997[79] in order to accelerate its development and subsequently China's relatively poorer western areas (see China Western Development strategy).[80] An important industrial area in western China,[81] Chongqing is also rapidly urbanising. For instance, statistics[82] suggest that new construction added approximately 137,000 square metres (1,470,000 square feet) daily of usable floor space to satisfy demands for residential, commercial and factory space. In addition, more than 1,300 people moved into the city daily, adding almost 100 million yuan (US$15 million) to the local economy.

Traditionally, due to its geographical remoteness, Chongqing and neighbouring Sichuan have been important military bases in weapons research and development.[83] Chongqing's industries have now diversified but unlike eastern China, its export sector is small due to its inland location. Instead, factories producing local-oriented consumer goods such as processed food, cars, chemicals, textiles, machinery, sports equipment and electronics are common.

Chongqing is China's third largest centre for motor vehicle production and the largest for motorcycles. In 2007, it had an annual output capacity of 1 million cars and 8.6 million motorcycles.[84] Leading makers of cars and motor bikes includes China's fourth biggest automaker; Changan Automotive Corp and Lifan Hongda Enterprise, as well as Ford Motor Company, with the US car giant having 3 plants in Chongqing. The municipality is also one of the nine largest iron and steel centres in China and one of the three major aluminium producers. Important manufacturers include Chongqing Iron and Steel Company and South West Aluminium which is Asia's largest aluminium plant.[85] Agriculture remains significant. Rice and fruits, especially oranges, are the area's main produce. Natural resources are also abundant with large deposits of coal, natural gas, and more than 40 kinds of minerals such as strontium and manganese. Coal reserves ≈ 4.8 billion tonnes. Chuandong Natural Gas Field is China's largest inland gas field with deposits of around 270 billion m3 – more than 1/5 of China's total. Has China's largest reserve of strontium (China has the world's 2nd biggest strontium deposit). Manganese is mined in the Xiushan area. although the mining sector has been criticised for being wasteful, heavily polluting and unsafe.[86] Chongqing is also planned to be the site of a 10 million ton capacity refinery operated by CNPC (parent company of PetroChina) to process imported crude oil from the Sino-Burma pipelines. The pipeline itself, though not yet finished, will eventually run from Sittwe (in Myanmar's western coast) through Kunming in Yunnan before reaching Chongqing[87] and it will provide China with fuels sourced from Myanmar, the Middle East and Africa. Recently, there has been a drive to move up the value chain by shifting towards high technology and knowledge intensive industries resulting in new development zones such as the Chongqing New North Zone (CNNZ).[88] Chongqing's local government is hoping through the promotion of favorable economic policies for the electronics and information technology sectors, that it can create a 400 billion RMB high technology manufacturing hub which will surpass its car industry and account for 25% of its exports.[89]

The city has also invested heavily in infrastructure to attract investment.[84][90] The network of roads and railways connecting Chongqing to the rest of China has been expanded and upgraded reducing logistical costs. Furthermore, the nearby Three Gorges Dam which is the world's largest, supplies Chongqing with power and allows oceangoing ships to reach Chongqing's Yangtze River port.[91] These infrastructure improvements have led to the arrivals of numerous foreign direct investors (FDI) in industries ranging from car to finance and retailing; such as Ford,[92] Mazda,[93] HSBC,[94] Standard Chartered Bank,[95] Citibank,[96] Deutsche Bank,[97] ANZ Bank,[98] Scotiabank,[99] Wal-Mart,[100] Metro AG[101] and Carrefour,[102] among other multinational corporations.

Chongqing's nominal GDP in 2011 reached 1001.1 billion yuan (US$158.9 billion) while registering an annual growth of 16.4%. However, its overall economic performance is still lagging behind eastern coastal cities such as Shanghai. For instance, its per capita GDP was 22,909 yuan (US$3,301) which is below the national average. Nevertheless, there is a massive government support to transform Chongqing into the region's economic, trade, and financial centre and use the municipality as a platform to open up the country's western interior to further development.[103]

Chongqing has been identified by the Economist Intelligence Unit in the November 2010 Access China White Paper as a member of the CHAMPS (Chongqing, Hefei, Anshan, Maanshan, Pingdingshan and Shenyang), an economic profile of the top 20 emerging cities in China.[104]

Economic and technological development zones

The city includes a number of economic and technological development zones:

- Chongqing Chemical Industrial Park[105]

- Chongqing Economic & Technological Development Zone[106]

- Chongqing Hi-Tech Industry Development Zone[107]

- Chongqing New North Zone (CNNZ)[108]

- Chongqing Export Processing Zone[109]

- Jianqiao Industrial Park (located in Dadukou District)[110]

- Liangjiang New Area[111]

- Liangjiang Cloud Computing Center (the largest of its kind in China)[112]

Chongqing itself is part of the West Triangle Economic Zone, along with Chengdu and Xi'an.

Education

Colleges and universities

- Chongqing University (重庆大学)

- Southwest University (西南大学)

- Southwest University of Political Science and Law (西南政法大学)

- Third Military Medical University (第三军医大学)

- Chongqing University of Posts and Telecommunications (重庆邮电大学)

- Chongqing University of Technology (重庆理工大学)

- Chongqing Jiaotong University (重庆交通大学)

- Chongqing Medical University (重庆医科大学)

- Chongqing Normal University (重庆师范大学)

- Chongqing Technology and Business University (重庆工商大学)

- Chongqing Three Gorges University (重庆三峡学院)

- Chongqing Telecommunication Institute (重庆通讯学院)

- Chongqing University of Science and Technology (重庆科技学院)

- Sichuan Fine Arts Institute (四川美术学院)

- Sichuan International Studies University (四川外国语大学)

- University of Logistics (后勤工程学院)

- Chongqing University of Arts and Science (重庆文理学院)

- Yangtze Normal University (长江师范学院)

- Chongqing University of Education (重庆第二师范学院)

Notable high schools

- Fuling Experimental High School (涪陵实验中学)

- Chongqing No.1 Secondary School (重庆一中)

- Chongqing Nankai Secondary School (重庆南开中学)

- Chongqing No.8 Secondary School (重庆八中)

- Bashu Secondary School (巴蜀中学)

- Chongqing Railway High School (重庆铁路中学)

- Chongqing Yucai Secondary School (育才中学)

- Chongqing Foreign Language School (The High School Affiliated to Sichuan International Studies University 重庆一外)

- Verakin High School of Chongqing (The 2nd Chongqing Foreign Language School, 重庆二外)

- Chongqing Qiujing High School (求精中学)

- High School Affiliated to Southwest University (西南大学附中)

- Chongqing NO.18 Secondary School (重庆十八中)

International schools

- Yew Chung International School of Chongqing (重庆耀中国际学校)[113]

- KL International School of Chongqing Bashu (重庆市诺林巴蜀外籍人员子女学校)[114]

Transport

Since its elevation to national-level municipality in 1997, the city has dramatically expanded its transportation infrastructure. With the construction of railways and expressways to the east and southeast, Chongqing is a major transportation hub in southwestern China.

As of October 2014, the municipality had 31 bridges across the Yangtze River including over a dozen in the city's urban core.[115] Aside from the city's first two Yangtze River bridges, which were built, respectively, in 1960 and 1977, all of the other bridges were completed since 1995.

Public transit

Public transport in Chongqing consists of metro, intercity railway, a ubiquitous bus system and the world's largest monorail network.

According to the Chongqing Municipal Government's ambitious plan in May 2007, Chongqing is investing 150 billion RMB over 13 years to finish a system that combines underground metro lines with heavy monorail (called 'light rail' in China).

As of 2017, four metro lines, the 14 km (8.7 mi) long CRT Line 1, a conventional subway, and the 19 km (12 mi) long heavy monorail CRT Line 2 (through Phase II), Line 3, a heavy monorail connects the airport and the southern part of downtown.,[116] Line 6, runs between Beibei, a commuter city in the far north to the centre.[117] Line 5 opened in late 2017.

By 2020 CRT will consist of 6 straight lines and 1 circular line resulting in 363.5 km (225.9 mi) of road and railway to the existing transportation infrastructure and 93 new train stations will be added to the 111 stations that are already in place.[118]

By 2050, Chongqing will have as many as 18 lines planned to be in operation.[119]

Aerial tramway

Chongqing is the only Chinese city that keeps public aerial tramways. Historically there were three aerial tramways in Chongqing: the Yangtze River Tramway, the Jialing River Tramway and the South Mountain Tramway. Currently, only Yangtze River Tramway is still operating and it is Class 4A Tourist Attractions in China. This tramway is 1,160 metres (3,810 feet) long, connecting the southern and northern banks of Yangtze River. The daily passenger volume is about 10,000.

River port

Chongqing is one of the most important inland ports in China. There are numerous luxury cruise ships that terminate at Chongqing, cruising downstream along the Yangtze River to Yichang, Wuhan, Nanjing or even Shanghai.[120] In the recent past, this provided virtually the only transportation option along the river. However, improved rail, expressways and air travel have seen this ferry traffic reduced or cancelled altogether. Most of the river ferry traffic consists of leisure cruises for tourists rather than local needs. Improved access by larger cargo vessels has been made due to the construction of the Three Gorges Dam. This allows bulk transport of goods along the Yangtze River. Coal, raw minerals and containerized goods provide the majority of traffic plying this section of the river. Several port handling facilities exist throughout the city, including many impromptu river bank sites.[121]

Railways

Major train stations in Chongqing:

- Chongqing railway station in Yuzhong, accessible via Metro Lines 1 & 3 (Lianglukou Metro station), is the city's oldest railway station and located near the city centre. The station handles mostly long-distance trains. There are plans for a major renovation and overhaul of this station, thus many services have been transferred to Chongqing North Railway Station.

- Chongqing North railway station is a station handling many long-distance services and high-speed rail services to Chengdu, Beijing and other cities. It was completed in 2006 and is connected to Metro Line.

- Chongqing West railway station is in Shapingba, a station handling many long-distance services and high-speed rail services to many cities. It is completed in 2018.

- Shapingba railway station is in Shapingba, near Shapingba CBD, accessible via Metro Line 1. It handles many local and regional train services. It is completed in 2018.

Chongqing is a major freight destination for rail with continued development with improved handling facilities. Due to subsidies and incentives, the relocation and construction of many factories in Chongqing has seen a huge increase in rail traffic.

Chongqing is a major rail hub regionally.

- Chengdu–Chongqing railway to Chengdu

- Sichuan-Guizhou railway to Guiyang

- Xiangyang–Chongqing railway to Hubei

- Chongqing–Huaihua railway to Hunan

- Chongqing-Suining railway (Sichuan province)

- Chongqing-Lichuan railway to Hubei

- Chongqing–Lanzhou railway (Gansu) railway

Highways

Traditionally, the road network in Chongqing has been narrow, winding and limited to smaller vehicles because of the natural terrain, large rivers and the huge population demands on the area, especially in the Yuzhong District. In other places, such as Jiangbei, large areas of homes and buildings have recently been cleared to improve the road network and create better urban planning. This has seen many tunnels and large bridges needing to be built across the city. Construction of many expressways have connected Chongqing to neighbouring provinces. Several ring roads have also been constructed. The natural mountainous terrain that Chongqing is built on makes many road projects difficult to construct, including for example some of the world's highest road bridges.[122]

Unlike many other Chinese cities, it is rare for motorbikes, electric scooters or bicycles to be seen on Chongqing Roads. This is due to the extremely hilly and mountainous nature of Chongqing's roads and streets. However, despite this, Chongqing is a large manufacturing centre for these types of vehicles.[123]

- Chongqing-Chengdu Expressway

- Chongqing-Chengdu 2nd Expressway (under construction)

- Chongqing-Wanzhou-Yichang Highway (Wanzhou-Yichang section under construction)

- Chongqing-Guiyang Highway

- Chongqing-Changsha Expressway (Xiushan-Changsha section under construction)

- Chongqing-Dazhou-Xi'a Highway (Dazhou-Xi'an section under construction)

- Chongqing-Suining Expressway

- Chongqing-Nanchong Expressway

- China National Highway 210

- China National Highway 212

Bridges

With so many bridges crossing the Yangtze and Jialing rivers in the urban area, Chongqing is sometimes known as the 'Bridge Capital of China'. The first important bridge in urban Chongqing was the Niujiaotuo Jialing River Bridge, built in 1958. The first bridge over the Yangtze river was the Shibanpo Yangtze River Bridge (or Chongqing Yangtze River Bridge) built in 1977.

As of 2014, within the area of the 9 districts, there were 20 bridges on the Yangtze river and 28 bridges on the Jialing river. The bridges in Chongqing exhibit a variety of shapes and structures, making Chongqing a showcase for bridge design.

Airports

The major airport of Chongqing is Chongqing Jiangbei International Airport (IATA: CKG, ICAO: ZUCK). It is located in Yubei District. The airport offers a growing network of direct flights to China, South East Asia, the Middle East, North America, and Europe. It is located 21 km (13 mi) north of the city-centre of Chongqing and serves as an important aviation hub for south-western China.[124] Jiangbei airport is a hub for China Southern Airlines, Chongqing Airlines, Sichuan Airlines, China Express Airlines, Shandong Airlines and Hainan Airlines's new China West Air. Chongqing also is a focus city of Air China, therefore it is very well connected with Star Alliance and Skyteam's international network. The airport currently has three parallel runways in operation. It serves domestic routes to most other Chinese cities, as well as international routes to Auckland, New York City, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Doha, Dubai, Seoul, Bangkok, Phuket, Osaka, Singapore, Chiang Mai, Phnom Penh, Siem Reap, Malé, Bali, Tokyo, Kuala Lumpur, Batam, Rome and Helsinki. As of 2018, Jiangbei Airport is the 9th busiest airport in terms of passenger traffic in mainland China.[125]

Currently, Jiangbei airport has three terminals. Chongqing Airport has metro access (CRT Line 3 and Line 10) to its central city, and two runways in normal use.[126]

There are two other airports in Chongqing Municipality: Qianjiang Wulingshan Airport (IATA: JIQ, ICAO: ZUQJ) and Wanzhou Wuqiao Airport (IATA: WXN, ICAO: ZUWX). They are both class 4C airports and serve passenger flights to some domestic destinations including Beijing, Shanghai and Kunming. Two more airports are being constructed soon: Wulong Xiannüshan Airport and Wushan Shennüfeng Airport.

Culture

Language

The language native to Chongqing is Southwestern Mandarin. More precisely, the great majority of the municipality, save for Xiushan, speak Sichuanese, including the primary Chengdu-Chongqing dialect and Minjiang dialect spoken in Jiangjin and Qijiang.[127] There are also a few speakers of Xiang and Hakka in the municipality, due to the great immigration wave to the Sichuan region (湖广填四川) during the Ming and Qing dynasties. In addition, in parts of southeastern Chongqing, the Miao and Tujia languages are also used by some Miao and Tujia people.[128]

Tourism

As the provisional Capital of China for almost ten years (1937 to 1945), the city was also known as one of the three headquarters of the Allies during World War II, as well as being a strategic center of many other wars throughout China's history. Chongqing has many historic war-time buildings or sites, some of which have since been destroyed. These sites include the People's Liberation Monument, located in the center of Chongqing city. It used to be the highest building in the area, but is now surrounded and dwarfed by numerous shopping centres. Originally named the Monument for the Victory over Axis Armies, it is the only building in China for that purpose.[129] Today, the monument serves as a symbol for the city. The General Joseph W. Stilwell Museum, dedicated to General "Vinegar Joe" Stilwell, a World War II general.[130] the air force cemetery in the Nanshan area, in memory of those air force personnel killed during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945), and the Red Rock Village Museum, a diplomatic site for the Communist Party in Chongqing led by Zhou Enlai during World War II, and Guiyuan, Cassia Garden, where Mao Zedong signed the "Double 10 (10 October) Peace Agreement" with the Kuomintang in 1945.[131]

- The Baiheliang Underwater Museum, China's first underwater museum,[132]

- The Memorial of Great Tunnel Massacre, a former air-raid shelter where a major massacre occurred during World War II.

- The Great Hall of the People in Chongqing is based on the Great Hall of the People in Beijing. This is one of the largest public assembly buildings in China which, though built in modern times, emulates traditional architectural styles. It is adjacent to the densely populated and hilly central district, with narrow streets and pedestrian only walkways,[133]

- The large domed Three Gorges Museum presents the history, culture, and environment of the Three Gorges area and Chongqing.

- Chongqing Art Museum is known for striking architecture.

- Chongqing Science and Technology Museum has an IMAX theatre.

- Luohan Si, a Ming dynasty temple,[134]

- Huangguan Escalator, the second longest escalator in Asia.

- Former sites for embassies of major countries during the 1940s. As the capital at that time, Chongqing had many residential and other buildings for these officials.[135]

- Wuxi County, noted as a major tourism area of Chongqing,[136]

- The Dazu Rock Carvings, in Dazu county, are a series of Chinese religious sculptures and carvings, dating back as far as the 7th century A.D., depicting and influenced by Buddhist, Confucian and Taoist beliefs. Listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the Dazu Rock Carvings are made up of 75 protected sites containing some 50,000 statues, with over 100,000 Chinese characters forming inscriptions and epigraphs.,[137]

- The Three Natural Bridges and Furong Cave in Wulong Karst National Geology Park, Wulong County are listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site as part of the South China Karst,[138][139]

- Ciqikou is a 1000-year-old town in the Shapingba District of Chongqing. It is also known as "Little Chongqing". The town, located next to the lower reaches of the Jialing River, was at one time an important source of china-ware and used to be a busy commercial dock during the Ming and Qing dynasties,[140]

- Fishing Town or Fishing City, also called the "Oriental Mecca" and "the Place That Broke God's Whip", is one of the three great ancient battlefields of China. It is noted for its resistance to the Mongol armies during the Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279) and the location where the Mongol leader Möngke Khan died in 1259,[141]

- Xueyu Cave in Fengdu County is the only example of a pure-white, jade-like karst cave in China,[142]

- Fengdu Ghost City in Fengdu County is the Gate of the Hell in traditional Chinese literature and culture.

- Snowy Jade Cave, see Xueyu Cave (above).

- Baidi Cheng, a peninsula in Yangtze River, known due to a famous poem by Li Bai.

- The Chongqing Zoo, a zoo that exhibits many rare species including the giant panda, the extremely rare South China tiger, and the African elephant.[143]

- Chongqing Amusement Park.

- Chongqing Grand Theatre, a performing arts centre.

- Foreigners' Street is an amusement park, including the Porcelain Palace, the world's largest toilet. Also the location of the abortive Love Land development in 2009.

- The Black Mountain Valley (Heishangu).[144]

Cuisine

Chongqing food is part of Sichuan cuisine. Chongqing is known for its spicy food. Its food is normally considered numbing because of the use of Sichuan pepper, also known as Sichuan peppercorn, containing hydroxy alpha sanshool. Chongqing's city centre has many restaurants and food stalls where meals often cost less than RMB10. Local specialties here include dumplings and pickled vegetables and, different from many other Chinese cuisines, Chongqing dishes are suitable for the solo diner as they are often served in small individual sized portions.[145] Among the delicacies and local specialties are these dishes:

- Chongqing hot pot (Huoguo) – Chongqing's local culinary specialty which was originally from Northern China. Tables in hot pot restaurants usually have a central pot, where food ordered by the customers is boiled in a spicy broth, items such as beef, pork, tripe, kidney slices, pork aorta and goose intestine are often consumed.[146]

- Chongqing Xiao Mian – a common lamian noodle dish tossed with chili oil and rich mixtures of spices and ingredients

- Jiangtuan fish – since Chongqing is located along Jialing River, visitors have a good opportunity to sample varieties of aquatic products. Among them, is a fish local to the region, Jiangtuan fish: Hypophthalmichthys nobilis although more commonly known as bighead carp.[147] The fish is often served steamed or baked.[148]

_(2269517013).jpg)

- Suan La Fen (Sour and Spicy Sweet-Potato Noodles) – Thick, transparent noodles of rubbery texture in a spicy vinegar soup.[149]

- Lazi Ji (Spicy Chicken) – A stir-fried dish consists of marinated then deep-fried pieces of chicken, dried Sichuan chilli peppers, Sichuan peppers, garlic, and ginger,[150] originated near Geleshan in Chongqing.[151]

- Quanshui Ji (Spring Water Chicken) – Quanshui Ji is cooked with the natural spring water in the Southern Mountain of Chongqing.

- Pork leg cooked with rock sugar – A common household dish of the Chongqing people, the finished dish, known as red in colour and tender in taste, has been described as having strong and sweet aftertaste.[152]

- Qianzhang (skimmed soy bean cream) – Qianzhang is the cream skimmed from soybean milk. In order to create this, several steps must be followed very carefully. First, soybeans are soaked in water, ground, strained, boiled, restrained several times and spread over gauze until delicate, snow-white cream is formed. The paste can also be hardened, cut into slivers and seasoned with sesame oil, garlic and chili oil. Another variation is to bake the cream and fry it with bacon, which is described as soft and sweet.[153]

Media

The Chongqing People's Broadcast Station is Chongqing's largest radio station.[154] The only municipal-level TV network is Chongqing TV, claimed to be the 4th largest television station in China.[155] Chongqing TV broadcasts many local-oriented channels, and can be viewed on many TV sets throughout China. The Chongqing Daily is the largest newspaper group, controlling more than 10 newspapers and one news website.[156]

Sports and recreation

Association football

Professional association football teams in Chongqing include:

- Chongqing Lifan (Chinese Super League)

- Chongqing F.C., folded

Chongqing Lifan is a professional Chinese football club who currently plays in the Chinese Super League. They are owned by the Chongqing-based Lifan Group, which manufactures motorcycles, cars and spare parts.[157] Originally called Qianwei (Vanguard) Wuhan, the club formed in 1995 to take part in the recently developed, fully professional Chinese football league system. They would quickly rise to top tier of the system and experience their greatest achievement in winning the 2000 Chinese FA Cup,[158] and coming in fourth within the league. However, since then they have struggled to replicate the same success, and have twice been relegated from the top tier.[159]

Chongqing FC was an association football club located in the city, and competed in China League One, the country's second-tier football division, before being relegated to the China League Two, and dissolving due to a resultant lack of funds.[160]

Basketball

Chongqing Soaring Dragons became the 20th team playing in Chinese Basketball Association in 2013. They play at Datianwan Arena, in the same sporting complex as Datianwan Stadium.[161] The team moved to Beijing in 2015 and is currently known as Beijing Royal Fighters.

Sport venues

Sport venues in Chongqing include:

- The Chongqing Olympic Sports Center is a multi-purpose stadium. It is currently used mostly for football matches, as it has a grass surface, and can hold 58,680. It was built in 2002 and was one of main venues for the 2004 AFC Asian Cup.[162]

- Yanghe Stadium is a multi-use stadium that is currently used mostly for football matches. The stadium holds 32,000 people, and is the home of Chongqing Lifan in the Chinese Super League. The stadium was purchased by the Lifan Group in 2001 for RMB80 million and immediately replaced Datianwan Stadium as the home of Chongqing Lifan.[163]

- Datianwan Stadium is a multi-purpose stadium that is currently used mostly for football matches. The stadium has a capacity 32,000 people, and up until 2001 was the home of Chongqing Lifan.[164]

Notable people

- Ba Manzi: a legendary hero of Ba kingdom in Zhou dynasty

- Ba Qing, the Widow: the earliest known female merchant in Chinese history who provided huge financial aid to Qin Shi Huang to construct the Great Wall

- Gan Ning: a general serving under warlord Sun Quan in the last years of Han dynasty

- Yan Yan: a loyal general during Three Kingdoms period

- Lanxi Daolong: a famous Buddhism monk and philosopher in Song dynasty who went to Japan and established the Kenchō-ji

- Qin Liangyu: a popular heroine in Ming dynasty who fought against Manchus

- Nie Rongzhen: marshal of the People's Liberation Army of China

- Liu Bocheng: an early leader of Chinese communist party during Anti-Japanese War

- Lu Zuofu: a notable patriotic industrialist and businessman who was a member of Chinese United League and a leader of Railway Protection Movement, established the Beibei District, Chongqing Natural History Museum, Jianshan High School, the Northern Hot Spring Park of Chongqing and Beibei Library, and served as the chief official of Food Bureau during Republic of China period.

- Liu Yongqing: wife of the former president and Party general secretary Hu Jintao

- Zhonghua Pang: a well-known calligrapher and geologist born in Sichuan but raised and lived in Chongqing

- Liu Xiaoqing: an actress

- Chen Kun: Chinese actor and singer

- Tian Liang: Olympic diving gold medalist

- Li Yundi: a pianist

- Karry Wang: A member of the pop band TFBoys and an actor

- Roy Wang: a singer-songwriter and member of TFBoys, also an actor and TV host

- Jiang Qinqin: an actress

- Li Hua: artist who studied in Europe

- Xiao Zhan: actor, singer, and member of the boy group X Nine

International relations

Consulates

| Consulate | Date | Consular District |

| Canada Consulate-General, Chongqing[165] | 05.1998 | Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan |

| United Kingdom Consulate-General, Chongqing[165] | 03.2000 | Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan |

| Cambodia Consulate-General, Chongqing[165] | 12.2004 | Chongqing, Hubei, Hunan, Shaanxi |

| Japan Consulate-General, Chongqing[165] | 01.2005 | Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan, Shaanxi |

| Denmark Consulate, Chongqing[165] | 07.2005 | Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan |

| Philippines Consulate-General, Chongqing[165] | 12.2008 | Chongqing, Guizhou, Yunnan |

| Hungary Consulate-General, Chongqing[165] | 02.2010 | Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan, Shaanxi, Gansu |

| Ethiopia Consulate-General, Chongqing[165] | 11.2011 | Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan |

| Italy Consulate-General, Chongqing[166] | 12.2013 | Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan |

| Netherlands Consulate-General, Chongqing[166] | 01.2014 | Chongqing, Sichuan, Shaanxi, Yunnan, Guizhou |

| Uruguay Consulate-General, Chongqing[167] | 12.2019 | Chongqing, Sichuan, Yunnan, Shaanxi, Gansu |

Twin towns – sister cities

Chongqing has sister city relationships with many cities of the world including:

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

See also

- Major national historical and cultural sites in Chongqing

- List of cities in China by population and built-up area

- List of twin towns and sister cities in China

Notes

- Total urban population in the municipality.

- Ch'ungk'ing, Ch'ung K'ing, Chongking, and other renderings are also found in older literature. The Beijing-based Standard Chinese pronunciation is rendered in Wade-Giles as Ch'ung-ch'ing, and in the latter 20th century this form was used officially in Taiwan and in Western academic literature.

- The data was collected by the Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS) of 2009 and by the Chinese Spiritual Life Survey (CSLS) of 2007, reported and assembled by Xiuhua Wang (2015)[75] in order to confront the proportion of people identifying with two similar social structures: ① Christian churches, and ② the traditional Chinese religion of the lineage (i. e. people believing and worshipping ancestral deities often organised into lineage "churches" and ancestral shrines). Data for other religions with a significant presence in China (deity cults, Buddhism, Taoism, folk religious sects, Islam, et. al.) was not reported by Wang.

- This may include:

- Buddhists;

- Confucians;

- Deity worshippers;

- Taoists;

- Members of folk religious sects;

- Small minorities of Muslims;

- And people not bounded to, nor practicing any, institutional or diffuse religion.

References

Citations

- "Doing Business in China – Survey". Ministry of Commerce of the People's Republic of China. Archived from the original on 5 August 2013. Retrieved 2013-08-05.

- "China: Chóngqìng (Districts and Counties) - Population Statistics, Charts and Map". Archived from the original on 17 February 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- 2015年重庆常住人口3016.55万人 继续保持增长态势 (in Chinese). Chongqing News. 28 January 2016. Archived from the original on 29 January 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- 重庆主城常住人口850万 户籍人口664.59万人 (in Chinese). ifeng.com. Archived from the original on 20 July 2019. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

- GDP-2019 is a preliminary data, and GDP-2018 is a revision based on the 2018 CASEN: "Home - Regional - Quarterly by Province" (Press release). China NBS. 15 April 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- "Sub-national HDI - Subnational HDI - Global Data Lab". globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- "City Flower". En.cq.gov.cn. Archived from the original on 30 June 2012. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- "City Tree". En.cq.gov.cn. Archived from the original on 30 June 2012. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- "Chongqing". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- "Chongqing" Archived 8 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine (US) and "Chongqing". Oxford Dictionaries UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- "Chongqing". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- "China's Direct-Controlled Municipalities". Geography.about.com. 14 March 1997. Archived from the original on 23 July 2012. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- 关于提请审议设立重庆直辖市的议案的说明_中国人大网 [Explanation on the proposal to consider the establishment of a municipality directly under the Central Government of China]. www.npc.gov.cn. Archived from the original on 17 May 2016. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- Alexander, Ruth (29 January 2012). "Which is the world's biggest city?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 6 August 2018. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- 最新中国城市人口数量排名(根据2010年第六次人口普查). www.elivecity.cn. 2012. Archived from the original on 3 March 2015. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- "Chongqing's Official Abbreviation". English.cri.cn. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- "EIU Report". Eiu.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2015.

- Kim Hunter Gordon, Jesse Watson (2011). Chongqing & The Three Gorges. pp. 38–40. ISBN 978-7-5022-5215-1.

- "Chongqing's History with the State of Ba". Chongqing Municipal Government. 6 December 2007. Archived from the original on 30 June 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

- "Ming Yuzhen Information". Neohumanism.com. Archived from the original on 7 February 2016. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

- Nicola di Cosmo; Don J. Wyatt (3 July 2003). Political Frontiers, Ethnic Boundaries, and Human Geographies in Chinese History. ISBN 9780203987957. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

- "The last Qing (Manchu) Dynasty 1644 - 1912 of China". Archived from the original on 7 November 2016. Retrieved 2015-08-19. The last Manchu dynasty

- "UK Consulate Page". Cq.xinhuanet.com. 30 December 2004. Archived from the original on 23 August 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- "Chongqing Opens Itself To Foreigners". Mitchellteachers.org. Archived from the original on 19 April 2012. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- "French Consulate Page". Cq.xinhuanet.com. 30 December 2004. Archived from the original on 23 August 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- "Japanese Consulate Page". Chongqing.cn.emb-japan.go.jp. Archived from the original on 9 July 2012. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- "US Consulate Page". Us-passport-service-guide.com. Archived from the original on 23 July 2012. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- "German Consulate Page". 2011.cqlib.cn. Archived from the original on 23 August 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- Danielson, Eric N. (2005). "Revisiting Chongqing: China's Second World War Temporary National Capital". Ournal of the Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Branch. 45: 175. JSTOR 23889883.

- "Chongqing - The Famous City in the Second World War : Photo Annals of Vanishing Sceneries(Book)".

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 21 August 2016. Retrieved 2015-08-19.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Chiang Kai-shek & Stilwell, Joseph

- "WWII Era History of Chongqing". .needham.k12.ma.us. 23 October 1944. Archived from the original on 6 June 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- "Chongqing becomes 5th National Central city". English.peopledaily.com.cn. 10 February 2010. Archived from the original on 18 May 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- "Establishment of the Liangjiang New Area". Gochina.scmp.com. 25 November 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 16 August 2016. Retrieved 2015-08-19.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Bashan Poems

- "Location of Chongqing". En.cq.gov.cn. Archived from the original on 30 June 2012. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 24 October 2016. Retrieved 2015-08-06.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Chongqing's bordering provinces

- Chongqing Topography. "Mountains in Sichuan and Chongqing". Fodors.com. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- "The Three Gorges Corp". Ctg.com.cn. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- "Yangtze River". Chinese National Tourism Office, US Chinese Embassy. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- Murphy, Ryan (28 December 2010). "Trip to Chongqing". Elevendegreesnorth.blogspot.com. Archived from the original on 18 December 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- "Poems of Li Bai". Poemhunter.com. Archived from the original on 27 June 2012. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 19 August 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Chongqing Mountains Data

- 中国气象局 国家气象信息中心 (in Chinese). Guangzhou Popular Science News Net (广州科普资讯网). 12 September 2007. Archived from the original on 18 March 2013. Retrieved 2014-11-12.

- "Extreme Temperatures Around the World". Archived from the original on 26 August 2010. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- "Chongqing Municipality". IES Global. Archived from the original on 11 October 2010. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- "Chongqing – City of Hills, Fog and Spicy Food". China.com. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- Lin, Yutang.1944. The Vigil of a Nation. The John Day Company. New York. 262 pages

- 中国气象数据网 - WeatherBk Data. China Meteorological Administration. Archived from the original on 23 September 2017. Retrieved 9 November 2018.

- 中国地面国际交换站气候标准值数据集 (1971–2000年) (in Chinese). China Meteorological Administration. May 2011. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- "Monthly weather forecast and climate - Chongqing, China". Weather Atlas. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- Page, Jeremy (15 March 2012). "Chongqing Party Chief Position". Online.wsj.com. Archived from the original on 24 November 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- Kuo, Ping-chia. "Chongqing History: The Modern Period". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Archived from the original on 22 June 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- "Chongqing, once a wartime capitol". En.cq.gov.cn. 14 March 1997. Archived from the original on 30 June 2012. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- Danielson, Eric N. (2005). "Revisiting Chongqing: China's Second World War Temporary National Capital". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Branch. 45: 175. JSTOR 23889883.

- "Qiu Shaoyun Memorial Hall". Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- Pike, John (21 November 2003). "A history of the 13th Army Group". Globalsecurity.org. Archived from the original on 13 March 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- 重庆调整部分行政区划:4区(县)并为2区. News.163.com. 17 March 2010. Archived from the original on 31 October 2011. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- 国家统计局统计用区划代码 (in Chinese). National Bureau of Statistics of the People's Republic of China. Archived from the original on 5 April 2013. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- 《保定经济统计年鉴2011》

- 中国2010年人口普查分乡、镇、街道资料 (1st ed.). Beijing: China Statistics Print. 2012. ISBN 978-7-5037-6660-2.

- 国务院人口普查办公室; 国家统计局人口和社会科技统计司, eds. (2012). 中国2010年人口普查分县资料. Beijing: China Statistics Print. ISBN 978-7-5037-6659-6.

- 《中国民政统计年鉴2012》

- "Position of Five Function Districts in Chongqing". Chongqing Municipal Government. 22 September 2013. Archived from the original on 21 November 2014. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- 五大功能区域: 都市功能核心区 [Five Functional Districts: Urban-function Core District]. CQNEWS Corporation. Archived from the original on 27 May 2015. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- 统计年鉴2014 [Statistical Yearbook 2014] (in Chinese). Statistics Bureau of Chongqing. 9 February 2015. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 1 May 2015.