Torture

Torture (from Latin tortus: to twist, to torment) is the act of deliberately inflicting severe physical or psychological suffering on someone by another as a punishment or in order to fulfill some desire of the torturer or force some action from the victim. Torture, by definition, is a knowing and intentional act; deeds which unknowingly or negligently inflict suffering or pain, without a specific intent to do so, are not typically considered torture.[1]

Torture has been carried out or sanctioned by individuals, groups, and states throughout history from ancient times to modern day, and forms of torture can vary greatly in duration from only a few minutes to several days or longer. Reasons for torture can include punishment, revenge, extortion, persuasion, political re-education, deterrence, coercion of the victim or a third party, interrogation to extract information or a confession irrespective of whether it is false, or simply the sadistic gratification of those carrying out or observing the torture.[2][3] Alternatively, some forms of torture are designed to inflict psychological pain or leave as little physical injury or evidence as possible while achieving the same psychological devastation. The torturer may or may not kill or injure the victim, but torture may result in a deliberate death and serves as a form of capital punishment. Depending on the aim, even a form of torture that is intentionally fatal may be prolonged to allow the victim to suffer as long as possible (such as half-hanging). In other cases, the torturer may be indifferent to the condition of the victim.

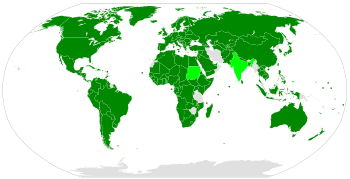

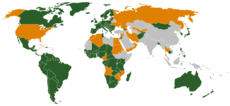

Although torture is sanctioned by some states, it is prohibited under international law and the domestic laws of most countries. Although widely illegal and reviled, there is an ongoing debate as to what exactly is and is not legally defined as torture. It is a serious violation of human rights, and is declared to be unacceptable (but not illegal) by Article 5 of the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Signatories of the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and the Additional Protocols I and II of 8 June 1977 officially agree not to torture captured persons in armed conflicts, whether international or internal. Torture is also prohibited for the signatories of the United Nations Convention Against Torture, which has 163 state parties.[4]

National and international legal prohibitions on torture derive from a consensus that torture and similar ill-treatment are immoral, as well as impractical, and information obtained by torture is far less reliable than that obtained by other techniques.[5][6][7] Despite these findings and international conventions, organizations that monitor abuses of human rights (e.g., Amnesty International, the International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims, Freedom from Torture, etc.) report widespread use condoned by states in many regions of the world.[8] Amnesty International estimates that at least 81 world governments currently practice torture, some of them openly.[9]

Definitions

International level

UN Convention Against Torture

The United Nations Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, which is currently in force since 26 June 1987, provides a broad definition of torture. Article 1.1 of the UN Convention Against Torture reads:

For the purpose of this Convention, the term "torture" means any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him, or a third person, information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity. It does not include pain or suffering arising only from, inherent in, or incidental to, lawful sanctions.[10]

This definition was restricted to apply only to nations and to government-sponsored torture and clearly limits the torture to that perpetrated, directly or indirectly, by those acting in an official capacity, such as government personnel, law enforcement personnel, medical personnel, military personnel, or politicians. It appears to exclude:

- torture perpetrated by gangs, hate groups, rebels, or terrorists who ignore national or international mandates;

- random violence during war; and

- punishment allowed by national laws, even if the punishment uses techniques similar to those used by torturers such as mutilation, whipping, or corporal punishment when practiced as lawful punishment. Some professionals in the torture rehabilitation field believe that this definition is too restrictive and that the definition of politically motivated torture should be broadened to include all acts of organized violence.[11]

Declaration of Tokyo

An even broader definition was used in the 1975 Declaration of Tokyo regarding the participation of medical professionals in acts of torture:

- For the purpose of this Declaration, torture is defined as the deliberate, systematic or wanton infliction of physical or mental suffering by one or more persons acting alone or on the orders of any authority, to force another person to yield information, to make a confession, or for any other reason.[12]

This definition includes torture as part of domestic violence or ritualistic abuse, as well as in criminal activities.

Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court

The Rome Statute is the treaty that set up the International Criminal Court (ICC). The treaty was adopted at a diplomatic conference in Rome on 17 July 1998 and went into effect on 1 July 2002. The Rome Statute provides the simplest definition of torture regarding the prosecution of war criminals by the International Criminal Court. Paragraph 1 under Article 7(e) of the Rome Statute provides that:

"Torture" means the intentional infliction of severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, upon a person in the custody or under the control of the accused; except that torture shall not include pain or suffering arising only from, inherent in or incidental to, lawful sanctions;[13]

Inter-American Convention to Prevent and Punish Torture

The Inter-American Convention to Prevent and Punish Torture, which is in force since 28 February 1987, defines torture more expansively than the United Nations Convention Against Torture. Article 2 of the Inter-American Convention reads:

For the purposes of this Convention, torture shall be understood to be any act intentionally performed whereby physical or mental pain or suffering is inflicted on a person for purposes of a criminal investigation, as a means of intimidation, as personal punishment, as a preventive measure, as a penalty, or for any other purpose. Torture shall also be understood to be the use of methods upon a person intended to obliterate the personality of the victim or to diminish his physical or mental capacities, even if they do not cause physical pain or mental anguish. The concept of torture shall not include physical or mental pain or suffering that is inherent in or solely the consequence of lawful measures, provided that they do not include the performance of the acts or use of the methods referred to in this article.[14]

Amnesty International

Since 1973, Amnesty International has adopted the simplest, broadest definition of torture. It reads:

- Torture is the systematic and deliberate infliction of acute pain by one person on another, or on a third person, in order to accomplish the purpose of the former against the will of the latter.[15]

European Court of Human Rights

The UN Convention Against Torture and Rome Statute and the definitions of torture include terms such as "severe pain or suffering". The international European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) has ruled on the difference between what is inhuman and degrading treatment and what is pain and suffering severe enough to be torture.

In Ireland v. United Kingdom (1979–1980) the ECHR ruled that the five techniques developed by the United Kingdom (wall-standing, hooding, subjection to noise, deprivation of sleep, and deprivation of food and drink), as used against fourteen detainees in Northern Ireland by the United Kingdom were "inhuman and degrading" and breached the European Convention on Human Rights, but did not amount to "torture".[16] In 2014, after new information was uncovered that showed the decision to use the five techniques in Northern Ireland in 1971–1972 had been taken by British ministers,[17] The Irish Government asked the ECHR to review its judgement. In 2018, by six votes to one, the Court declined.[18]

In Aksoy v. Turkey (1997) the Court found Turkey guilty of torture in 1996 in the case of a detainee who was suspended by his arms while his hands were tied behind his back.[19]

The Court's ruling that the five techniques did not amount to torture was later cited by the United States and Israel to justify their own interrogation methods,[20] which included the five techniques.[21]

The Court has ruled that every form of torture is strictly prohibited in all circumstances:[22]

Article 3 of the Convention enshrines one of the most fundamental values of democratic societies. Even in the most difficult of circumstances, such as the fight against terrorism or crime, the Convention prohibits in absolute terms torture or inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

Article 3 makes no provision for exceptions and no derogation from it is permissible under Article 15 § 2 even in the event of a public emergency threatening the life of the nation (...).

Municipal level

United States

U.S. Code § 2340

Title 18 of the United States Code contains the definition of torture in 18 U.S.C. § 2340, which is only applicable to persons committing or attempting to commit torture outside of the United States.[23] It reads:

As used in this chapter—

- (1) "torture" means an act committed by a person acting under the color of law specifically intended to inflict severe physical or mental pain or suffering (other than pain or suffering incidental to lawful sanctions) upon another person within his custody or physical control;

- (2) "severe mental pain or suffering" means the prolonged mental harm caused by or resulting from—

- (A) the intentional infliction or threatened infliction of severe physical pain or suffering;

- (B) the administration or application, or threatened administration or application, of mind-altering substances or other procedures calculated to disrupt profoundly the senses or the personality;

- (C) the threat of imminent death; or

- (D) the threat that another person will imminently be subjected to death, severe physical pain or suffering, or the administration or application of mind-altering substances or other procedures calculated to disrupt profoundly the senses or personality; and

- (3) "United States" means the several states of the United States, the District of Columbia, and the commonwealths, territories, and possessions of the United States.

In order for the United States to assume control over this jurisdiction, the alleged offender must be a U.S. national or the alleged offender must be present in the United States, irrespective of the nationality of the victim or alleged offender. Any person who conspires to commit an offense shall be subject to the same penalties (other than the penalty of death) as the penalties prescribed for an actual act or attempting to commit an act, the commission of which was the object of the conspiracy.[23]

Torture Victim Protection Act of 1991

The Torture Victim Protection Act of 1991 provides remedies to individuals who are victims of torture by persons acting in an official capacity of any foreign nation. The definition is similar to the U.S. Code § 2340, which reads:

(b) TORTURE.—For the purposes of this Act—

- (1) the term "torture" means any act, directed against an individual in the offender's custody or physical control, by which severe pain or suffering (other than pain or suffering arising only from or inherent in, or incidental to, lawful sanctions), whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on that individual for such purposes as obtaining from that individual or third person information or a confession, punishing that individual for an act that individual or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, intimidating or coercing that individual or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind; and

- 2) mental pain or suffering refers to prolonged mental harm caused by or resulting from—

- (A) the intentional infliction or threatened infliction of severe physical pain or suffering;

- (B) the administration or application, or threatened administration or application, of mind-altering substances or other procedures calculated to disrupt profoundly the senses or the personality;

- (C) the threat of imminent death; or

- (D) the threat that another individual will imminently be subjected to death, severe physical pain or suffering, or the administration or application of mind-altering substances or other procedures calculated to disrupt profoundly the senses or personality.[24]

History

In the study of the history of torture, some authorities rigidly divide the history of torture per se from the history of capital punishment, while noting that most forms of capital punishment are extremely painful. Torture grew into an ornate discipline, where calibrated violence served two functions: to investigate and produce confessions and to attack the body as a form of punishment. Entire populaces of towns would show up to witness an execution by torture in the public square. Those who had been "spared" torture were commonly locked barefooted into the stocks, where children took delight in rubbing feces into their hair and mouths.[25]

Deliberately painful methods of torture and execution for severe crimes were taken for granted as part of justice until the development of Humanism in 17th-century philosophy, and "cruel and unusual punishment" came to be denounced in the English Bill of Rights of 1689. The Age of Enlightenment in the Western world further developed the idea of universal human rights. The adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948 marks the recognition at least nominally of a general ban of torture by all UN member states.

Its effect in practice is limited, however, as the Declaration is not ratified officially and does not have a legally binding character in international law, but is rather considered part of customary international law. Several countries still practice torture today. Some countries have legally codified it, and others have claimed that it is not practiced while maintaining the use of torture in secret.[26]

Since the days when Roman law prevailed throughout Europe, torture has been regarded as subtending three classes or degrees of suffering.[27] First-degree torture typically took the forms of whipping and beating but did not mutilate the body. The most prevalent modern example is bastinado, a technique of beating or whipping the soles of the bare feet. Second-degree torture consisted almost entirely of crushing devices and procedures, including screw presses or "bone vises" that crushed thumbs, toes, knees, feet, even teeth and skulls in a wide variety of ways. A wide array of "boots"—-machines designed to slowly crush feet—-are representative. Finally, third-degree tortures savagely mutilated the body in numerous dreadful ways, incorporating spikes, blades, boiling oil, and controlled fire. The serrated iron tongue shredder; the red-hot copper basin for destroying eyesight (abacination, q.v.); and the stocks that forcibly held the prisoner's naked feet, glistening with lard, directly over red-hot coals (foot roasting, q.v.) until the skin and foot muscles were burnt black and the bones fell to ashes are examples of torture in the third degree.

Antiquity

Judicial torture was probably first applied in Persia, either by Medes or Achaemenid Empire. Over time torture has been used as a means of reform, inducing public terror, interrogation, spectacle, and sadistic pleasure. The ancient Greeks and Romans used torture for interrogation. Until the 2nd century AD, torture was used only on slaves (with a few exceptions).[28] After this point it began to be extended to all members of the lower classes.[29] A slave's testimony was admissible only if extracted by torture, on the assumption that slaves could not be trusted to reveal the truth voluntarily. This torture occurred to break the bond between a master and his slave. Slaves were thought to be incapable of lying under torture.[30]

Middle Ages

Medieval and early modern European courts used torture, depending on the crime of the accused and his or her social status. Torture was deemed a legitimate means to extract confessions or to obtain the names of accomplices or other information about a crime, although many confessions were greatly invalid due to the victim being forced to confess under great agony and pressure. It was permitted by law only if there was already half-proof against the accused.[31] Torture was used in continental Europe to obtain corroborating evidence in the form of a confession when other evidence already existed.[32] Often, defendants already sentenced to death would be tortured to force them to disclose the names of accomplices. Torture in the Medieval Inquisition began in 1252 with a papal bull Ad Extirpanda and ended in 1816 when another papal bull forbade its use.

A highly esteemed torture in the times of the Inquisition as a good means of interrogating "taciturn" heretics and wizards was the interrogation chair.[33]

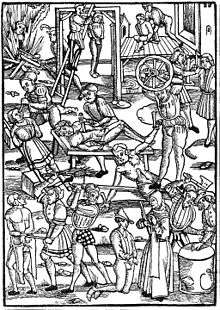

Torture was usually conducted in secret, in underground dungeons. By contrast, torturous executions were typically public, and woodcuts of English prisoners being hanged, drawn and quartered show large crowds of spectators, as do paintings of Spanish auto-da-fé executions, in which heretics were burned at the stake. Torture was also used during this time period as a means of reform, spectacle, to induce fear into the public, and most popularly as a punishment for treason.

Medieval torture devices were varied. One old English chronicle from the Early Medieval period reads, "They hanged them by the thumbs, or by the head, and hung fires on their feet; they put knotted strings about their heads and writhed them so that it went to the brain ... Some they put in a chest that was short, and narrow, and shallow, and put sharp stones therein, and pressed the man therein so that they broke all his limbs ... I neither can nor may tell all the wounds or all the tortures which they inflicted on wretched men in this land."[34] Tortures later in the Middle Ages consisted of whipping; the crushing of thumbs, feet, legs, and heads in iron presses; burning the flesh; and tearing out teeth, fingernails, and toenails with red-hot iron forceps. Limb-smashing and drowning were also popular medieval tortures. Specific devices were also created and used during this time, including the rack, the Pear (also mentioned in Grose's Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue (1811) as "Choak [sic.] Pears," and described as being "formerly used in Holland."), thumbscrews, animals like rats, the iron chair, and the cat o nine tails.[35]

Early modern period

.jpg)

During the early modern period, the torture of witches took place. In 1613, Anton Praetorius described the situation of the prisoners in the dungeons in his book Gründlicher Bericht Von Zauberey und Zauberern (Thorough Report about Sorcery and Sorcerers). He was one of the first to protest against all means of torture.

While secular courts often treated suspects ferociously, Will and Ariel Durant argued in The Age of Faith that many of the most vicious procedures were inflicted upon pious heretics by even more pious friars. The Dominicans gained a reputation as some of the most fearsomely innovative torturers in medieval Spain.[36]

Torture was continued by Protestants during the Renaissance against teachers who they viewed as heretics. In 1547 John Calvin had Jacques Gruet arrested in Geneva, Switzerland. Under torture he confessed to several crimes including writing an anonymous letter left in the pulpit which threatened death to Calvin and his associates.[37] The Council of Geneva had him beheaded with Calvin's approval.[38][39][40][41] Suspected witches were also tortured and burnt by Protestant leaders, though more often they were banished from the city, as well as suspected spreaders of the plague, which was considered a more serious crime.[42]

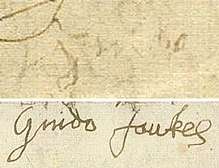

In England the trial by jury developed considerable freedom in evaluating evidence and condemning on circumstantial evidence, making torture to extort confessions unnecessary. For this reason, in England, a regularized system of judicial torture never existed and its use was limited to political cases. Torture was in theory not permitted under English law, but in Tudor and early Stuart times, under certain conditions, torture was used in England. For example, the confession of Marc Smeaton at the trial of Anne Boleyn was presented in written form only, either to hide from the court that Smeaton had been tortured on the rack for four hours, or because Thomas Cromwell was worried that he would recant his confession if cross-examined. When Guy Fawkes was arrested for his role in the Gunpowder Plot of 1605 he was tortured until he revealed all he knew about the plot. This was not so much to extract a confession, which was not needed to prove his guilt, but to extract from him the names of his fellow conspirators. By this time torture was not routine in England and a special warrant from King James I was needed before he could be tortured. The wording of the warrant shows some concerns for humanitarian considerations, specifying that the severity of the methods of interrogation were to be increased only gradually until the interrogators were sure that Fawkes had told all he knew.

The privy council attempted to have John Felton who stabbed George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham to death in 1628 questioned under torture on the rack, but the judges resisted, unanimously declaring its use to be contrary to the laws of England.[43] Torture was abolished in England around 1640 (except peine forte et dure, which was abolished in 1772).

In Colonial America, women were sentenced to the stocks with wooden clips on their tongues or subjected to the "dunking stool" for the gender-specific crime of talking too much.[44] Certain Native American peoples, especially in the area that later became the eastern half of the United States, engaged in the sacrificial torture of war captives.[45] And Spanish colonial officials in what is today the southwestern United States and northern Mexico often resorted to torture to extract confessions from rebellious Native Americans, as evidenced by the case of the Pima leader Joseph Romero 'Canito' in 1686.[46]

In the 17th century, the number of incidents of judicial torture decreased in many European regions. Johann Graefe in 1624 published Tribunal Reformation, a case against torture. Cesare Beccaria, an Italian lawyer, published in 1764 "An Essay on Crimes and Punishments", in which he argued that torture unjustly punished the innocent and should be unnecessary in proving guilt. Voltaire (1694–1778) also fiercely condemned torture in some of his essays.

While in Egypt in 1798, Napoleon Bonaparte wrote to Major-General Berthier regarding the validity of torture as an interrogation tool:

The barbarous custom of whipping men suspected of having important secrets to reveal must be abolished. It has always been recognized that this method of interrogation, by putting men to the torture, is useless. The wretches say whatever comes into their heads and whatever they think one wants to believe. Consequently, the Commander-in-Chief forbids the use of a method which is contrary to reason and humanity.[47]

European states abolished torture from their statutory law in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. England abolished torture in about 1640 (except peine forte et dure, which England only abolished in 1772), Scotland in 1708, Prussia in 1740, Denmark around 1770, Russia in 1774, Austria and Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1776, Italy in 1786, France in 1789, and Baden in 1831.[48][49][50] Sweden was the first to do so in 1722 and the Netherlands did the same in 1798. Bavaria abolished torture in 1806 and Württemberg in 1809. In Spain, the Napoleonic conquest put an end to torture in 1808. Norway abolished it in 1819 and Portugal in 1826. The last European jurisdictions to abolish legal torture were Portugal (1828) and the canton of Glarus in Switzerland (1851).[51]

Methods of torture

Tortures included the chevalet, in which an accused witch sat on a pointed metal horse with weights strung from her feet.[52] Sexual humiliation torture included forced sitting on red-hot stools.[53] Gresillons, also called pennywinkis in Scotland, or pilliwinks, crushed the tips of fingers and toes in a vise-like device.[54] The Spanish Boot, or "leg-screw", used mostly in Germany and Scotland, was a steel boot that was placed over the leg of the accused and was tightened. The pressure from the squeezing of the boot would break the shin bone-in pieces. An anonymous Scotsman called it "The most severe and cruel pain in the world".[55] Ingenious variants of the Spanish boot were also designed to slowly crush feet between iron plates armed with terrifying spikes. The echelle more commonly known as the "ladder" or "rack" was a long table that the accused would lie upon and be stretched violently. The torture was used so intensely that on many occasions the victim's limbs would be pulled out of the socket and, at times, the limbs would even be torn from the body entirely. On some special occasions a tortillon was used in conjunction with the ladder which would severely squeeze and mutilate the genitals at the same time as the stretching was occurring.[54] Similar to the ladder was the "lift". It too stretched the limbs of the accused; in this instance however the victim's feet were strapped to the ground and their arms were tied behind their back before a rope was tied to their hands and lifted upwards. This caused the arms to break before the portion of the stretching began.[55] Finally, the judicial system of King James favored the use of the turkas, an ingenious and savage iron instrument for destroying the nails of the fingers and toes. The sharp point of the instrument was first pushed under the nail to the root, splitting the nail down the centerline. Pincers then grabbed either edge of the destroyed nail and slowly tore it away from the nail bed. Other common tortures included the strappado, a system of weights and pulleys with which the prisoner was trussed up and jerked in order to dislocate his limbs; the water torture, by which he was maintained at the very edge of drowning; and the so-called torture by fire, in which the bare feet, immobilized in iron stocks and smeared with lard, were slowly barbecued over red-hot coals.

Since 1948

Modern sensibilities have been shaped by a profound reaction to the war crimes and crimes against humanity committed by the Axis Powers and Allied Powers in the Second World War, which have led to a sweeping international rejection of most if not all aspects of the practice.[56] Even as many states engage in torture, few wish to be described as doing so, either to their own citizens or to the international community. A variety of devices bridge this gap, including state denial, "secret police", "need to know", a denial that given treatments are torturous in nature, appeal to various laws (national or international), the use of jurisdictional argument and the claim of "overriding need". Throughout history and today, many states have engaged in torture, albeit unofficially. Torture ranges from physical, psychological, political, interrogations techniques, and also includes rape of anyone outside of law enforcement.[57]

According to scholar Ervand Abrahamian, although there were several decades of prohibition of torture that spread from Europe to most parts of the world, by the 1980s, the taboo against torture was broken and torture "returned with a vengeance," propelled in part by television and an opportunity to break political prisoners and broadcast the resulting public recantations of their political beliefs for "ideological warfare, political mobilization, and the need to win 'hearts and minds.'"[58]

In the years 2004 and 2005, over 16 countries were documented using torture.[59] In an attempt to bring global awareness, Human Rights Watch has created an internet site to alert people to news and multimedia publications about torture occurring worldwide.[59] The International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims [IRCT] made a global analysis of torture based on [Amnesty International, 2001], [Human Rights Watch, 2003], [United Nations, 2002], [U.S. Department of State, 2002] yearly human rights reports. These reports showed that torture and ill-treatment are consistently report based on all four sources in 32 countries. At least two reports the use of torture and ill-treatment in at least 80 countries. These reports confirm the assumption that torture occurs in a quarter of the world's countries on a regular basis. This global prevalence of torture is estimated on the magnitude of particular high-risk groups and the amount of torture used by these groups. "Such groups comprise refugees and persons who are or have been under torture."[57] According to professor Darius Rejali, although dictatorships may have used tortured "more, and more indiscriminately", it was modern democracies, "the United States, Britain, and France" who "pioneered and exported techniques that have become the lingua franca of modern torture: methods that leave no marks."[60] The practice of torture used as the oppression against political opponents or could be a part of a criminal investigation or interrogation techniques in order to obtain the desired information and keep law enforcement empowered over everyday citizens.[57]

The modern concept of torture methods that leave no physical evidence is noted in 1995 by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-IV within the changing definition of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder PTSD. This revised definition included psychological torture stating: "Expresses concern that the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders definition of posttraumatic stress disorder does not include those forms of psychological torture in which the physical integrity of a person is not threatened. It is suggested that any diagnostic criterion that characterizes the traumatic stressors leading to PTSD should be expressed in such a way that psychological forms of torture are included."[61] After 1995, the sweeping definition of changes from 'any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether mental or physical, is intentionally inflicted on a person' to including the terms psychological torture and including examples such as, interrogation techniques range from sleep deprivation, solitary confinement, fear, and humiliation to severe sexual and cultural humiliation and use of threats and phobias to induce fear of death or injury.[62]

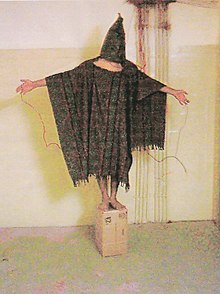

Torture still occurs in a small number of liberal democracies despite several international treaties such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the UN Convention Against Torture making torture illegal. Despite such international conventions, torture cases continue to arise such as the 2004 Abu Ghraib torture and prisoner abuse scandal committed by personnel of the United States Army. The U.S. Constitution and U.S. law prohibits the use of torture, yet such human rights violations occurred during the War on Terror under the euphemism Enhanced interrogation. The United States revised the previous torture policy in 2009 under the Obama Administration. This revision revokes Executive Order 13440 of 20 July 2007, under which the incident at Abu Ghraib and prisoner abuse occurred. Executive Order 13491 of 22 January 2009 further defines United States policy on torture and interrogation techniques in an attempt to further prevent another torture incident.[63] Yet apparently the practice continues, albeit outsourced.[64]

According to the findings of Dr. Christian Davenport of the University of Notre Dame, Professor William Moore of Florida State University, and David Armstrong of Oxford University during their torture research, evidence suggests that non-governmental organizations have played the most determinant factor for stopping torture once it gets started.[65] Preliminary research suggests that it is civil society, not government institutions, that can stop torture once it has begun. This inability to control abuse and torture in society creates an imperfect Democracy non-compliant with internationally agreed-upon standards for civil and political rights.[57] Many organizations serve to expose widespread human rights violations and hold individuals accountable to the international community.

Historical methods of execution and capital punishment

For most of recorded history, capital punishments were often cruel and inhumane. Severe historical penalties include breaking wheel, boiling to death, flaying, slow slicing, disembowelment, crucifixion, impalement, crushing, stoning, execution by burning, dismemberment, sawing, decapitation, scaphism, or necklacing.[66]

Slow slicing, or death by/of a thousand cuts, was a form of execution used in China from roughly 900 AD to its abolition in 1905. According to apocryphal lore, líng che began when the torturer, wielding an extremely sharp knife, began by putting out the eyes, rendering the condemned incapable of seeing the remainder of the torture and, presumably, adding considerably to the psychological terror of the procedure. Successive rather minor cuts chopped off ears, nose, tongue, fingers, toes, and such before proceeding to grosser cuts that removed large collops of flesh from more sizable parts, e.g., thighs and shoulders. The entire process was said to last three days, and to total 3,600 cuts. The heavily carved bodies of the deceased were then put on a parade for a show in the public. More typical was to bribe the executioner to administer hasty death to the victim after a small number of dramatic slices inflicted for showmanship.[67][68]

Impalement was a method of torture and execution whereby a person is pierced with a long stake. The penetration can be through the sides, from the rectum, or through the mouth or vagina. This method would lead to slow, painful, death. Often, the victim was hoisted into the air after partial impalement. Gravity and the victim's own struggles would cause him to slide down the pole. Death could take many days. Impalement was frequently practiced in Asia and Europe throughout the Middle Ages. Vlad III Dracula and Ivan the Terrible have passed into legend as major users of the method.[69]

The breaking wheel was a torturous capital punishment device used in the Middle Ages and early modern times for public execution by cudgeling to death, especially in France and Germany. In France the condemned were placed on a cart-wheel with their limbs stretched out along the spokes over two sturdy wooden beams. The wheel was made to slowly revolve. Through the openings between the spokes, the executioner hit the victim with an iron hammer that could easily break the victim's bones. This process was repeated several times per limb. Once his bones were broken, he was left on the wheel to die. It could take hours, even days, before shock and dehydration caused death. The punishment was abolished in Germany as late as 1827.[70]

Etymology

The word 'torture' comes from the French torture, originating in the Late Latin tortura and ultimately deriving the past participle of torquere meaning 'to twist'.[71][50] The word is also used loosely to describe more ordinary discomforts that would be accurately described as tedious rather than painful; for example, "making this spreadsheet was torture!"

According to Diderot's Encyclopédie, torture was also referred to as "the question" in seventeenth-century France. This term is derived from torture's use in criminal cases: as the accused is tortured, the torturers would typically ask questions to the accused in an effort to learn more about the crime.[72]

Religious perspectives

Roman Catholic Church

Throughout the Early Middle Ages, the Catholic Church generally opposed the use of torture during criminal proceedings. This is evident from a letter sent by Pope Saint Nicholas the Great to Khan Boris of the Bulgars in AD 866, delivered in response to a series of questions from the former and concerned with the ongoing Christianisation of Bulgaria. Ad Consulta Vestra (as entitled in Latin) declared judicial torture to be a practice that was fundamentally contrary to divine law.[73] The Pontiff made it a point of incontrovertible truth that, in his own words: "confession [to a crime] should be spontaneous, not compelled, and should not be elicited with violence but rather proferred voluntarily". He argued for an alternative and more humane procedure, in which the accused person would be required to swear an oath of innocence upon the "holy Gospel that he did not commit [the crime] which is laid against him and from that moment on the matter is [to be put] at an end".[73] Nicholas likewise stressed in the same letter that "those who refuse to receive the good of Christianity and sacrifice and bend their knees to idols" were to be moved towards accepting the true faith "by warnings, exhortations, and reason rather than by force," emphasising to this end that "violence should by no means be inflicted upon them to make them believe. For everything which is not voluntary, cannot be good".[73]

In the High Middle Ages, the Church became increasingly concerned with the perceived threat posed to its existence by resurgent heresy, in particular, that attributed to a purported sect known as the Cathars. Catharism had its roots in the Paulician movement in Armenia and eastern Byzantine Anatolia and the Bogomils of the First Bulgarian Empire. Consequently, the Church began to enjoin secular rulers to extirpate heresy (lest the ruler's Catholic subjects are absolved from their allegiance), and in order to coerce heretics or witnesses "into confessing their errors and accusing others," decided to sanction the use of methods of torture, already utilized by secular governments in other criminal procedures due to the recovery of Roman Law, in the medieval inquisitions.[74][75] However, Pope Innocent IV, in the Bull Ad extirpanda (15 May 1252), stipulated that the inquisitors were to "stop short of danger to life or limb".[76]

The modern Church's views regarding torture have changed drastically, largely reverting to the earlier stance. In 1953, in an address to the 6th International Congress of Penal Law, Pope Pius XII approvingly reiterated the position of Pope Nicholas the Great over a thousand years before him, when his predecessor had unilaterally opposed the use of judicial torture, stating:

Preliminary juridical proceedings must exclude physical and psychological torture and the use of drugs: first of all, because they violate a natural right, even if the accused is indeed guilty, and secondly because all too often they give rise to erroneous results...About eleven hundred years ago, in 866, the great Pope Nicholas I replied in the following way to a question posed by a people which had just come into contact with Christianity: 'If a thief or a bandit is caught, and denies what is imputed to him, you say among you that the judge should beat him on the head with blows and pierce his sides with iron spikes, until he speaks the truth. That, neither divine nor human law admits: the confession must not be forced, but spontaneous; it must not be extorted, but voluntary; lastly, if it happens that, after having inflicted these sufferings, you discover absolutely nothing concerning that with which you have charged the accused, are you not ashamed then at least, and do you not recognize how impious your judgment was? Likewise, if the accused, unable to bear such tortures, admits to crimes which he has not committed, who, I ask you, has the responsibility for such an impiety? Is it not he who forced him to such a deceitful confession? Furthermore, if some one utters with his lips what is not in his mind, it is well known that he is not confessing, he is merely speaking. Put away these things, then, and hate from the bottom of your heart what heretofore you have had the folly to practice; in truth, what fruit did you then draw from that of which you are now ashamed?'

Who would not wish that, during the long period of time elapsed since then, justice had never laid this rule aside! The need to recall the warning given eleven hundred years ago is a sad sign of the miscarriages of juridical practice in the twentieth century.[77]

Thus, the Catechism of the Catholic Church (published in 1994) condemns the use of torture as a grave violation of human rights. In No. 2297-2298 it states:

Torture, which uses physical or moral violence to extract confessions, punish the guilty, frighten opponents, or satisfy hatred is contrary to respect for the person and for human dignity... In times past, cruel practices were commonly used by legitimate governments to maintain law and order, often without protest from the Pastors of the Church, who themselves adopted in their own tribunals the prescriptions of Roman law concerning torture. Regrettable as these facts are, the Church always taught the duty of clemency and mercy. She forbade clerics to shed blood. In recent times it has become evident that these cruel practices were neither necessary for public order nor in conformity with the legitimate rights of the human person. On the contrary, these practices led to ones even more degrading. It is necessary to work for their abolition. We must pray for the victims and their tormentors.

Sharia law

The prevalent view among jurists of sharia law is that torture is not permitted under any circumstances.[78][79]

In Judaism

Torture has no presence within halakha (Jewish law). There did once exist a system of capital and corporal punishment in Judaism, as well as a flagellation statute for non-capital offences, but it was all abolished by the Sanhedrin during the Second Temple period.

Maimonides issued a ruling in the case of a man who was ordered by a beth din (religious court) to divorce his wife and refused that "we coerce him until he states 'I want to.'"[80] This is only true in cases where specific grounds for the verdict exist.[81] In the 1990s, some activist rabbis had interpreted this statement to mean that torture could be applied against husbands in troubled marriages in order to force them into granting gittin (religious divorces) to their wives.[82] One such group, the New York divorce coercion gang, was broken up by the Federal Bureau of Investigation in 2013.[83]

Laws against torture

On 10 December 1948, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). Article 5 states, "No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment."[84] Since that time, a number of other international treaties have been adopted to prevent the use of torture. The most notable treaties relating to torture are the United Nations Convention Against Torture and the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and their Additional Protocols I and II of 8 June 1977.[85]

United Nations Convention Against Torture

The United Nations Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment came into force in June 1987. The most relevant articles are Articles 1, 2, 3, and 16.

Article 1

1. For the purposes of this Convention, the word "torture" means any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or third person information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity. It does not include pain or suffering arising only from, inherent in or incidental to lawful sanctions.

2. This article is without prejudice to any international instrument or national legislation which does or may contain provisions of wider application.

Article 2

1. Each State Party shall take effective legislative, administrative, judicial or other measures to prevent acts of torture in any territory under its jurisdiction.

2. No exceptional circumstances whatsoever, whether a state of war or a threat of war, internal political instability or any other public emergency, may be invoked as a justification of torture.3. An order from a superior officer or a public authority may not be invoked as a justification of torture.

Article 3

1. No State Party shall expel, return ("refouler") or extradite a person to another State where there are substantial grounds for believing that he would be in danger of being subjected to torture.

2. For the purpose of determining whether there are such grounds, the competent authorities shall take into account all relevant considerations including, where applicable, the existence in the State concerned of a consistent pattern of gross, flagrant or mass violations of human rights.

Article 16

1. Each State Party shall undertake to prevent in any territory under its jurisdiction other acts of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment which do not amount to torture as defined in Article I when such acts are committed by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity. In particular, the obligations contained in articles 10, 11, 12 and 13 shall apply with the substitution for references to torture of references to other forms of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

2. The provisions of this Convention are without prejudice to the provisions of any other international instrument or national law which prohibits cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment or which relates to extradition or expulsion.

Note several points:

- Article 1: Torture is "severe pain or suffering".[86] The European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) influences discussions on this area of international law. See the section Other conventions for more details on the ECHR ruling.

- Article 2: There are "no exceptional circumstances whatsoever where a state can use torture and not break its treaty obligations."[87]

- Article 16: Obliges signatories to prevent "acts of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment", in all territories under their jurisdiction.[nb 1][nb 2]

Optional Protocol to the UN Convention Against Torture

The Optional Protocol to the Convention Against Torture (OPCAT) entered into force on 22 June 2006 as an important addition to the UNCAT. As stated in Article 1, the purpose of the protocol is to "establish a system of regular visits undertaken by independent international and national bodies to places where people are deprived of their liberty, in order to prevent torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment."[88] Each state ratifying the OPCAT, according to Article 17, is responsible for creating or maintaining at least one independent national preventive mechanism for torture prevention at the domestic level.[89]

UN Special Rapporteur on Torture

The United Nations Commission on Human Rights in 1985 decided to appoint an expert, a special rapporteur, to examine questions relevant to torture. The position has been extended up to date.[90] On 1 November 2016, Prof. Nils Melzer, took up the function of UN Special Rapporteur on Torture.[91] He warned that specific weapons and riot control devices used by police and security forces could be illegal.[91]

Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court

The Rome Statute, which established the International Criminal Court (ICC), provides for criminal prosecution of individuals responsible for genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. The statute defines torture as "intentional infliction of severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, upon a person in the custody or under the control of the accused; except that torture shall not include pain or suffering arising only from, inherent in or incidental to, lawful sanctions". Under Article 7 of the statute, torture may be considered a crime against humanity "when committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian population, with knowledge of the attack".[92] Article 8 of the statute provides that torture may also, under certain circumstances, be prosecuted as a war crime.[93]

The ICC came into existence on 1 July 2002[94] and can only prosecute crimes committed on or after that date.[95] The court can generally exercise jurisdiction only in cases where the accused is a national of a state party to the Rome Statute, the alleged crime took place on the territory of a state party, or a situation is referred to the court by the United Nations Security Council.[96] The court is designed to complement existing national judicial systems: it can exercise its jurisdiction only when national courts are unwilling or unable to investigate or prosecute such crimes.[97] Primary responsibility to investigate and punish crimes is therefore reserved to individual states.[98]

Geneva Conventions

The four Geneva Conventions provide protection for people who fall into enemy hands. The conventions do not clearly divide people into combatant and non-combatant roles. The conventions refer to:

- "wounded and sick combatants or non-combatants"

- "civilian persons who take no part in hostilities, and who, while they reside in the zones, perform no work of a military character"[99]

- "Members of the armed forces of a Party to the conflict as well as members of militias or volunteer corps forming part of such armed forces"

- "Members of other militias and members of other volunteer corps, including those of organized resistance movements belonging to a Party to the conflict and operating in or outside their own territory, even if this territory is occupied"

- "Members of regular armed forces who profess allegiance to a government or an authority not recognized by the Detaining Power"

- "Persons who accompany the armed forces without actually being members thereof, such as civilian members of military aircraft crews, war correspondents, supply contractors, members of labour units or of services responsible for the welfare of the armed forces"

- "Members of crews, including masters, pilots, and apprentices, of the merchant marine and the crews of civil aircraft of the Parties to the conflict"

- "Inhabitants of a non-occupied territory, who on the approach of the enemy spontaneously take up arms to resist the invading forces, without having had time to form themselves into regular armed units".[100]

The first (GCI), second (GCII), third (GCIII), and fourth (GCIV) Geneva Conventions are the four most relevant for the treatment of the victims of conflicts. All treaties states in Article 3, in similar wording, that in a non-international armed conflict, "Persons taking no active part in the hostilities, including members of armed forces who have laid down their arms... shall in all circumstances be treated humanely." The treaty also states that there must not be any "violence to life and person, in particular murder of all kinds, mutilation, cruel treatment and torture" or "outrages upon personal dignity, in particular, humiliating and degrading treatment".[101][102][103][104]

GCI covers wounded combatants in an international armed conflict. Under Article 12, members of the armed forces who are sick or wounded "shall be respected and protected in all circumstances. They shall be treated humanely and cared for by the Party to the conflict in whose power they may be, without any adverse distinction founded on sex, race, nationality, religion, political opinions, or any other similar criteria. Any attempts upon their lives, or violence to their persons, shall be strictly prohibited; in particular, they shall not be murdered or exterminated, subjected to torture or to biological experiments".

GCII covers shipwreck survivors at sea in an international armed conflict. Under Article 12, persons "who are at sea and who are wounded, sick or shipwrecked, shall be respected and protected in all circumstances, it being understood that the term "shipwreck" means shipwreck from any cause and includes forced landings at sea by or from aircraft. Such persons shall be treated humanely and cared for by the Parties to the conflict in whose power they may be, without any adverse distinction founded on sex, race, nationality, religion, political opinions, or any other similar criteria. Any attempts upon their lives, or violence to their persons, shall be strictly prohibited; in particular, they shall not be murdered or exterminated, subjected to torture or to biological experiments".

GCIII covers the treatment of prisoners of war (POWs) in an international armed conflict. In particular, Article 17 says that "No physical or mental torture, nor any other form of coercion, may be inflicted on prisoners of war to secure from them information of any kind whatever. Prisoners of war who refuse to answer may not be threatened, insulted or exposed to unpleasant or disadvantageous treatment of any kind." POW status under GCIII has far fewer exemptions than "Protected Person" status under GCIV. Captured combatants in an international armed conflict automatically have the protection of GCIII and are POWs under GCIII unless they are determined by a competent tribunal to not be a POW (GCIII Article 5).

GCIV covers most civilians in an international armed conflict, and says they are usually "Protected Persons" (see exemptions section immediately after this for those who are not). Under Article 32, civilians have the right to protection from "murder, torture, corporal punishments, mutilation, and medical or scientific experiments...but also to any other measures of brutality whether applied by civilian or military agents."

Geneva Convention IV exemptions

GCIV provides an important exemption:

Where in the territory of a Party to the conflict, the latter is satisfied that an individual protected person is definitely suspected of or engaged in activities hostile to the security of the State, such individual person shall not be entitled to claim such rights and privileges under the present Convention [ie GCIV] as would ... be prejudicial to the security of such State ... In each case, such persons shall nevertheless be treated with humanity (GCIV Article 5)

Also, nationals of a State not bound by the Convention are not protected by it, and nationals of a neutral State in the territory of a combatant State, and nationals of a co-belligerent State, cannot claim the protection of GCIV if their home state has normal diplomatic representation in the State that holds them (Article 4), as their diplomatic representatives can take steps to protect them. The requirement to treat persons with "humanity" implies that it is still prohibited to torture individuals not protected by the Convention.

The George W. Bush administration afforded fewer protections, under GCIII, to detainees in the "War on Terror" by codifying the legal status of an "unlawful combatant". If there is a question of whether a person is a lawful combatant, he (or she) must be treated as a POW "until their status has been determined by a competent tribunal" (GCIII Article 5). If the tribunal decides that he is an unlawful combatant, he is not considered a protected person under GCIII. However, if he is a protected person under GCIV he still has some protection under GCIV and must be "treated with humanity and, in case of trial, shall not be deprived of the rights of fair and regular trial prescribed by the present Convention" (GCIV Article 5).[nb 3]

Additional Protocols to the Geneva Conventions

There are two additional protocols to the Geneva Convention: Protocol I (1977), relating to the protection of victims of international armed conflicts and Protocol II (1977), relating to the protection of victims of non-international armed conflicts. These clarify and extend the definitions in some areas, but to date, many countries, including the United States, have either not signed them or have not ratified them.

Protocol I does not mention torture but it does affect the treatment of POWs and Protected Persons. In Article 5, the protocol explicitly involves "the appointment of Protecting Powers and of their substitute" to monitor that the Parties to the conflict are enforcing the Conventions.[105] The protocol also broadens the definition of a lawful combatant in wars against "alien occupation, colonial domination, and racist regimes" to include those who carry arms openly but are not wearing uniforms, so that they are now lawful combatants and protected by the Geneva Conventions—although only if the Occupying Power has ratified Protocol I. Under the original conventions, combatants without a recognizable insignia could be treated as war criminals, and potentially be executed. It also mentions spies and defines who is a mercenary. Mercenaries and spies are considered an unlawful combatant, and not protected by the same conventions.

Protocol II "develops and supplements Article 3 [relating to the protection of victims of non-international armed conflicts] common to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949 without modifying its existing conditions of application" (Article 1). Any person who does not take part in or ceased to take part in hostilities is entitled to humane treatment. Among the acts prohibited against these persons are, "Violence to the life, health and physical or mental well-being of persons, in particular, murder as well as cruel treatment such as torture, mutilation or any form of corporal punishment" (Article 4.a), "Outrages upon personal dignity, in particular humiliating and degrading treatment, rape, enforced prostitution and any form of indecent assault" (Article 4.e), and "Threats to commit any of the foregoing acts" (Article 4.h).[106] Clauses in other articles implore humane treatment of enemy personnel in an internal conflict. These have a bearing on torture, but no other clauses explicitly mention torture.

Other conventions

In accordance with the optional UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (1955), "corporal punishment, punishment by placing in a dark cell, and all cruel, inhuman or degrading punishments shall be completely prohibited as punishments for disciplinary offences."[107] The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, (16 December 1966), explicitly prohibits torture and "cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment" by signatories.[108]

- European agreements

In 1950 during the Cold War, the participating member states of the Council of Europe signed the European Convention on Human Rights. The treaty was based on the UDHR. It included the provision for a court to interpret the treaty, and Article 3 "Prohibition of torture" stated; "No one shall be subjected to torture or to inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment."[109]

In 1978, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that the five techniques of "sensory deprivation" were not torture as laid out in Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights, but were "inhuman or degrading treatment"[110] (see Accusations of use of torture by United Kingdom for details). This case occurred nine years before the United Nations Convention Against Torture came into force and had an influence on thinking about what constitutes torture ever since.[111]

On 26 November 1987, the member states of the Council of Europe, meeting at Strasbourg, adopted the European Convention for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (ECPT). Two additional Protocols amended the Convention, which entered into force on 1 March 2002. The Convention set up the Committee for the Prevention of Torture to oversee compliance with its provisions.

- Inter-American Convention

The Inter-American Convention to Prevent and Punish Torture, currently ratified by 18 nations of the Americas and in force since 28 February 1987, defines torture more expansively than the United Nations Convention Against Torture.

For the purposes of this Convention, torture shall be understood to be any act intentionally performed whereby physical or mental pain or suffering is inflicted on a person for purposes of a criminal investigation, as a means of intimidation, as personal punishment, as a preventive measure, as a penalty, or for any other purpose. Torture shall also be understood to be the use of methods upon a person intended to obliterate the personality of the victim or to diminish his physical or mental capacities, even if they do not cause physical pain or mental anguish. The concept of torture shall not include physical or mental pain or suffering that is inherent in or solely the consequence of lawful measures, provided that they do not include the performance of the acts or use of the methods referred to in this article.[14]

Supervision of anti-torture treaties

The Istanbul Protocol, an official UN document, is the first set of international guidelines for documentation of torture and its consequences. It became a United Nations official document in 1999.

Under the provisions of OPCAT that entered into force on 22 June 2006 independent international and national bodies regularly visit places where people are deprived of their liberty, to prevent torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. Each state that ratified the OPCAT, according to Article 17, is responsible for creating or maintaining at least one independent national preventive mechanism for torture prevention at the domestic level.

The European Committee for the Prevention of Torture, citing Article 1 of the European Convention for the Prevention of Torture, states that it will, "by means of visits, examine the treatment of persons deprived of their liberty with a view to strengthening, if necessary, the protection of such persons from torture and from inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment".[112]

In times of armed conflict between a signatory of the Geneva Conventions and another party, delegates of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) monitor the compliance of signatories to the Geneva Conventions, which includes monitoring the use of torture. Human rights organizations, such as Amnesty International, the World Organization Against Torture, and Association for the Prevention of Torture work actively to stop the use of torture throughout the world and publish reports on any activities they consider to be torture.[113]

Municipal law

States that ratified the United Nations Convention Against Torture have a treaty obligation to include the provisions into municipal law. The laws of many states therefore formally prohibit torture. However, such de jure legal provisions are by no means a proof that, de facto, the signatory country does not use torture. To prevent torture, many legal systems have a right against self-incrimination or explicitly prohibit undue force when dealing with suspects.

The French 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, of constitutional value, prohibits submitting suspects to any hardship not necessary to secure his or her person.

The U.S. Constitution and U.S. law prohibits the use of unwarranted force or coercion against any person who is subject to interrogation, detention, or arrest. The Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution includes protection against self-incrimination, which states that "[n]o person...shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself". This serves as the basis of the Miranda warning, which U.S. law enforcement personnel issue to individuals upon their arrest. Additionally, the U.S. Constitution's Eighth Amendment forbids the use of "cruel and unusual punishments," which is widely interpreted as prohibiting torture. Finally, 18 U.S.C. § 2340[114] et seq. define and forbid torture committed by U.S. nationals outside the United States or non-U.S. nationals who are present in the United States. As the United States recognizes customary international law, or the law of nations, the U.S. Alien Tort Claims Act and the Torture Victim Protection Act also provides legal remedies for victims of torture outside of the United States. Specifically, the status of torturers under the law of the United States, as determined by a famous legal decision in 1980, Filártiga v. Peña-Irala, 630 F.2d 876 (2d Cir. 1980), is that, "the torturer has become, like the pirate and the slave trader before him, hostis humani generis, an enemy of all mankind."[115]

Exclusion of evidence obtained under torture

International law

Article 15 of the 1984 United Nations Convention Against Torture specify that:

Each State Party shall ensure that any statement which is established to have been made as a result of torture shall not be invoked as evidence in any proceedings, except against a person accused of torture as evidence that the statement was made.

A similar provision is also found in Article 10 of the 1985 Inter-American Convention to Prevent and Punish Torture:

No statement that is verified as having been obtained through torture shall be admissible as evidence in a legal proceeding, except in a legal action taken against a person or persons accused of having elicited it through acts of torture, and only as evidence that the accused obtained such statement by such means.

These provisions have the double dissuasive effect of nullifying any utility in using torture with the purpose of eliciting a confession, as well as confirming that should a person extract statements by torture, this can be used against him or her in criminal proceedings.[116] The reason for this is because experience has shown that under torture, or even under a threat of torture, a person will say or do anything solely to avoid the pain. As a result, there is no way to know whether or not the resulting statement is actually correct. If any court relies on any evidence obtained from torture regardless of validity, it provides an incentive for state officials to force a confession, creating a marketplace for torture, both domestically and overseas.[117]

Within national borders

Most states have prohibited their legal systems from accepting evidence that is extracted by torture. The question of the use of evidence obtained under torture has arisen in connection with prosecutions during the War on Terror in the United Kingdom and the United States.

United Kingdom

In 2003, the United Kingdom's Ambassador to Uzbekistan, Craig Murray, suggested that it was "wrong to use information gleaned from torture".[119] The unanimous Law Lords judgment on 8 December 2005 confirmed this position. They ruled that, under English law tradition, "torture and its fruits" could not be used in court.[120] But the information thus obtained could be used by the British police and security services as "it would be ludicrous for them to disregard information about a ticking bomb if it had been procured by torture."[121]

Murray's accusations did not lead to any investigation by his employer, the FCO, and he resigned after disciplinary action was taken against him in 2004. The Foreign and Commonwealth Office itself was being investigated by the National Audit Office because of accusations that it has victimized, bullied and intimidated its own staff.[122]

Murray later stated that he felt that he had unwittingly stumbled upon what has been called "torture by proxy".[123] He thought that Western countries moved people to regimes and nations where it was known that information would be extracted by torture, and made available to them.

Murray states that he was aware from August 2002 "that the CIA were bringing in detainees to Tashkent from Bagram airport Afghanistan, who were handed over to the Uzbek security services (SNB). I presumed at the time that these were all Uzbek nationals—that may have been a false presumption. I knew that the CIA were obtaining intelligence from their subsequent interrogation by the SNB." He goes on to say that he did not know at the time that any non-Uzbek nationals were flown to Uzbekistan and although he has studied the reports by several journalists and finds their reports credible he is not a firsthand authority on this issue.[124]

During a House of Commons debate on 7 July 2009, MP David Davis accused the UK government of outsourcing torture, by allowing Rangzieb Ahmed to leave the country (even though they had evidence against him upon which he was later convicted for terrorism) to Pakistan, where it is said the Inter-Services Intelligence was given the go-ahead by the British intelligence agencies to torture Ahmed. Davis further accused the government of trying to gag Ahmed, stopping him coming forward with his accusations after he had been imprisoned back in the UK. He said, there was "an alleged request to drop his allegations of torture: if he did that, they could get his sentence cut and possibly give him some money. If this request to drop the torture case is true, it is frankly monstrous. It would at the very least be a criminal misuse of the powers and funds under the Government's Contest strategy, and at worst a conspiracy to pervert the course of justice."[125]

United States

In May 2008, Susan J. Crawford, the official overseeing prosecutions before the Guantanamo military commissions, declined to refer for trial the case of Mohammed al-Qahtani because she said, "we tortured [him]."[126][127] Crawford said that a combination of techniques with clear medical consequences amounted to the legal definition of torture and that torture "tainted everything going forward."[126]

On 28 October 2008, Guantanamo military judge Stephen R. Henley ruled that the government cannot use statements made as a result of torture in the military commission case against Afghan national Mohammed Jawad. The judge held that Jawad's alleged confession to throwing a grenade at two U.S. service members and an Afghan interpreter was obtained after armed Afghan officials on 17 December 2002,[128] threatened to kill Jawad and his family. The government had previously told the judge that Jawad's alleged confession while in Afghan custody was central to the case against him. Hina Shamsi, staff attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union National Security Project stated: "We welcome the judge's decision that death threats constitute torture and that evidence obtained as a result must be excluded from trial. Unfortunately, evidence obtained through torture and coercion is pervasive in military commission cases that, by design, disregard the most fundamental due process rights, and no single decision can cure that."[129] A month later, on 19 November, the judge again rejected evidence gathered through coercive interrogations in the military commission case against Afghan national Mohammed Jawad, holding that the evidence collected while Jawad was in U.S. custody on 17–18 December 2002, cannot be admitted in his trial,[130] mainly because the U.S. interrogator had blindfolded and hooded Jawad in order to frighten him.[131]

In the 2010 New York trial of Ahmed Khalfan Ghailani who was accused of complicity in the 1998 bombings of U.S. embassies in Tanzania and Kenya, Judge Lewis A. Kaplan ruled evidence obtained under coercion inadmissible.[132] The ruling excluded an important witness, whose name had been extracted from the defendant under duress.[133] The jury acquitted him of 280 charges and convicted on only one charge of conspiracy.[132][133]

Judge Rotenberg Center

The Judge Rotenberg Center is a school in Canton, Massachusetts that uses the methods of ABA to perform behavior modification in children with developmental disabilities. Before it was banned in 2020, the center used a device called a Graduated Electronic Decelerator (GED) to deliver electric skin shocks as aversives. The Judge Rotenberg center has been condemned by the United Nations for torture as a result of this practice.[134] While many human rights and disability rights advocates have campaigned to shut down the center, as of 2020 it remains open. Six students have died of preventable causes at the school since it opened in 1971.[135][136]

Aspects

Ethical arguments

Torture has been criticized on humanitarian and moral grounds, on the grounds that evidence extracted by torture is unreliable, and because torture corrupts institutions that tolerate it.[137] Besides degrading the victim, torture debases the torturer: American advisors alarmed at torture by their South Vietnamese allies early in the Vietnam War concluded that "if a commander allowed his officers and men to fall into these vices [they] would pursue them for their own sake, for the perverse pleasure they drew from them."[138] The consequent degeneracy destroyed discipline and morale: "[a] soldier had to learn that he existed to uphold law and order, not to undermine it."[138]

Organizations like Amnesty International argue that the universal legal prohibition is based on a universal philosophical consensus that torture and ill-treatment are repugnant, abhorrent, and immoral.[139] But since shortly after the 11 September 2001 attacks there has been a debate in the United States about whether torture is justified in some circumstances. Some people, such as Alan M. Dershowitz and Mirko Bagaric, have argued the need for information outweighs the moral and ethical arguments against torture.[140][141] However, after coercive practices were banned, interrogators in Iraq saw an increase of 50 percent more high-value intelligence. Maj. Gen. Geoffrey D. Miller, the American commander in charge of detentions and interrogations, stated "a rapport-based interrogation that recognizes respect and dignity, and having very well-trained interrogators, is the basis by which you develop intelligence rapidly and increase the validity of that intelligence."[6] Others including Robert Mueller, FBI Director since 5 July 2001, have pointed out that despite former Bush Administration claims that waterboarding has "disrupted a number of attacks, maybe dozens of attacks", they do not believe that evidence gained by the U.S. government through what supporters of the techniques call "enhanced interrogation" has disrupted a single attack and no one has come up with a documented example of lives saved thanks to these techniques.[142][7] On 19 June 2009, the US government announced that it was delaying the scheduled release of declassified portions of a report by the CIA Inspector General that reportedly cast doubt on the effectiveness of the "enhanced interrogation" techniques employed by CIA interrogators, according to references to the report contained in several Bush-era Justice Department memos declassified in the Spring of 2009 by the US Justice Department.[143][144][145]

The ticking time bomb scenario, a thought experiment, asks what to do to a captured terrorist who has placed a nuclear bomb in a populated area. If the terrorist is tortured, he may explain how to defuse the bomb. The scenario asks if it is ethical to torture the terrorist. A 2006 BBC poll held in 25 nations gauged support for each of the following positions:[146]

- Terrorists pose such an extreme threat that governments should be allowed to use some degree of torture if it may gain information that saves innocent lives.

- Clear rules against torture should be maintained because any use of torture is immoral and will weaken international human rights.

An average of 59% of people worldwide rejected torture. However, there was a clear divide between those countries with strong rejection of torture (such as Italy, where only 14% supported torture) and nations where rejection was less strong. Often this lessened rejection is found in countries severely and frequently threatened by terrorist attacks. E.g., Israel, despite its Supreme Court outlawing torture in 1999, showed 43% supporting torture, but 48% opposing, India showed 37% supporting torture and only 23% opposing.[147]

Within nations, there is a clear divide between the positions of members of different ethnic groups, religions, and political affiliations, sometimes reflecting distinctions between groups considering themselves threatened or victimized by terror acts and those from the alleged perpetrator groups. For example, the study found that among Jews in Israel 53% favored some degree of torture and only 39% wanted strong rules against torture while Muslims in Israel were overwhelmingly against any use of torture, unlike Muslims polled elsewhere. Differences in general political views also can matter. In one 2006 survey by the Scripps Center at Ohio University, 66% of Americans who identified themselves as strongly Republican supported torture, compared to 24% of those who identified themselves as strongly Democratic.[148] In a 2005 U.S. survey 72% of American Catholics supported the use of torture in some circumstances compared to 51% of American secularists.[149] A Pew survey in 2009 similarly found that the religiously unaffiliated are the least likely (40 percent) to support torture, and that the more a person claims to attend church, the more likely he or she is to condone torture; among racial/religious groups, white evangelical Protestants were far and away the most likely (62 percent) to support inflicting pain as a tool of interrogation.[150]