Sexual assault

Sexual assault is an act in which a person intentionally sexually touches another person without that person's consent, or coerces or physically forces a person to engage in a sexual act against their will.[1] It is a form of sexual violence, which includes rape (forced vaginal, anal or oral penetration or drug facilitated sexual assault), groping, child sexual abuse or the torture of the person in a sexual manner.[1][2][3]

| Sexual assault | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Emergency medicine |

Definition

Generally, sexual assault is defined as unwanted sexual contact.[4] The National Center for Victims of Crime states:[5]

Sexual assault takes many forms including attacks such as rape or attempted rape, as well as any unwanted sexual contact or threats. Usually a sexual assault occurs when someone touches any part of another person's body in a sexual way, even through clothes, without that person's consent.

In the United States, the definition of sexual assault varies widely among the individual states. However, in most states sexual assault occurs when there is lack of consent from one of the individuals involved. Consent must take place between two adults who are not incapacitated and can change during any time during the sexual act.

Types

Child sexual abuse

Child sexual abuse is a form of child abuse in which an adult or older adolescent abuses a child for sexual stimulation.[6][7] Forms of child sexual abuse include asking or pressuring a child to engage in sexual activities (regardless of the outcome), indecent exposure of the genitals to a child, displaying pornography to a child, actual sexual contact against a child, physical contact with the child's genitals, viewing of the child's genitalia without physical contact, or using a child to produce child pornography,[6][8][9] including live streaming sexual abuse.[10]

The effects of child sexual abuse include depression,[11] post-traumatic stress disorder,[12] anxiety,[13] propensity to re-victimization in adulthood,[14] physical injury to the child, and increased risk for future interpersonal violence perpetration among males, among other problems.[15][16] Sexual abuse by a family member is a form of incest. It is more common than other forms of sexual assault on a child and can result in more serious and long-term psychological trauma, especially in the case of parental incest.[17]

Approximately 15 to 25 percent of women and 5 to 15 percent of men were sexually abused when they were children.[18][19][20][21][22][23] Most sexual abuse offenders are acquainted with their victims. Approximately 30 percent of the perpetrators are relatives of the child - most often brothers, fathers, mothers, sisters and uncles or cousins. Around 60 percent are other acquaintances such as friends of the family, babysitters, or neighbors. Strangers are the offenders in approximately 10 percent of child sexual abuse cases.[18]

Studies have shown that the psychological damage is particularly severe when sexual assault is committed by parents against children due to the incestuous nature of the assault.[17] Incest between a child or adolescent and a related adult has been identified as the most widespread form of child sexual abuse with a huge capacity for damage to a child.[17] Often, sexual assault on a child is not reported by the child for several of the following reasons:

- children are too young to recognize their victimization or put it into words

- they were threatened or bribed by the abuser

- they feel confused by fearing the abuser

- they are afraid no one will believe them

- they blame themselves or believe the abuse is a punishment

- they feel guilty for consequences to the perpetrator[24]

Many states have criminalized sexual contact between teachers or school administrators and students, even if the student is over the age of consent.[25]

Domestic violence

Domestic violence is violence or other abuse by one person against another in a domestic setting, such as in marriage or cohabitation. It is strongly correlated with sexual assault. Not only can domestic abuse be emotional, physical, psychological and financial, but it can be sexual. Some of the signs of sexual abuse are similar to those of domestic violence.[26]

Elderly sexual assault

About 30 percent of people age 65 or older who are sexually assaulted in the U.S. report it to the police.[27] Assailants may include strangers, caretakers, adult children, spouses and fellow facility residents.[27]

Groping

The term groping is used to define the touching or fondling of another person in a sexual way without the person's consent. Groping may occur under or over clothing.

Rape

Outside of law, the term rape (sexual intercourse or other forms of sexual penetration carried out against a person without that person's consent) is often used interchangeably with sexual assault.[28][29] Although closely related, the two terms are technically distinct in most jurisdictions. Sexual assault typically includes rape and other forms of non-consensual sexual activity.[4][30]

Abbey et al. state that female victims are much more likely to be assaulted by an acquaintance, such as a friend or co-worker, a dating partner, an ex-boyfriend or a husband or other intimate partner than by a complete stranger.[31] In a study of hospital emergency room treatments for rape, Kaufman et al. stated that the male victims as a group sustained more physical trauma and were more likely to have been a victim of multiple assaults from multiple assailants. It was also stated that male victims were more likely to have been held captive longer.[32]

In the U.S., rape is a crime committed primarily against youth. A national telephone survey on violence against women conducted by the National Institute of Justice and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that 18% of women surveyed had experienced a completed or attempted rape at some time in their lives. Of these, 22% were younger than 12 years and 32% were between 12 and 17 years old when they were first raped.[33][23]

In the U.K., attempted rape under the Criminal Attempts Act 1981 is a 'sexual offence' within section 31(1) of the Criminal Justice Act 1991.[34]

The removal of a condom during intercourse without the consent of the sex partner, known as stealthing, may be treated as a sexual assault or rape.[35]

Sexual harassment

Sexual harassment is intimidation, bullying or coercion of a sexual nature. It may also be defined as the unwelcome or inappropriate promise of rewards in exchange for sexual favors.[36] The legal and social definition of what constitutes sexual harassment differ widely by culture. Sexual harassment includes a wide range of behaviors from seemingly mild transgressions to serious forms of abuse. Some forms of sexual harassment overlap with sexual assault.[37]

In the United States, sexual harassment is a form of discrimination which violates Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. According to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC): "Unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature constitutes sexual harassment when submission to or rejection of this conduct explicitly or implicitly affects an individual's employment, unreasonably interferes with an individual's work performance or creates an intimidating, hostile or offensive work environment."[38]

In the United States:

- 79% of victims are women, 21% are men

- 51% are harassed by a supervisor

- Business, Trade, Banking, and Finance are the biggest industries where sexual harassment occurs

- 12% received threats of termination if they did not comply with their requests

- 26,000 people in the armed forces were assaulted in 2012[18]

- 302 of the 2,558 cases pursued by victims were prosecuted

- 38% of the cases were committed by someone of a higher rank

- Sexual harassment is a form of sex discrimination that violates Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

- Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 is a federal law that prohibits employers from discriminating against employees on the basis of sex, race, color, national origin, and religion. It generally applies to employers with 15 or more employees, including federal, state, and local governments. Title VII also applies to private and public colleges and universities, employment agencies, and labor organizations.[19]

- "It shall be an unlawful employment practice for an employer … to discriminate against any individual with respect to his compensation, terms, conditions, or privileges of employment, because of such individual’s race, color, religion, sex, or national origin."[20]

Mass sexual assault

Mass sexual assault takes place in public places and in crowds. It involves large groups of men surrounding and assaulting a woman, groping, manual penetration, and frottage, but usually stopping short of penile rape.

Emotional effects

Aside from physical traumas, rape and other sexual assault often result in long-term emotional effects, particularly in child victims. These can include, but are not limited to: denial, learned helplessness, genophobia, anger, self-blame, anxiety, shame, nightmares, fear, depression, flashbacks, guilt, rationalization, moodswings, numbness, promiscuity, loneliness, social anxiety, difficulty trusting oneself or others, difficulty concentrating. Being the victim of sexual assault may lead to the development of posttraumatic stress disorder, addiction, major depressive disorder or other psychopathologies. Family and friends experience emotional scarring including a strong desire for revenge, a desire to "fix" the problem and/or move on, and a rationalization that "it wasn't that bad".[24]

Physical effects

While sexual assault, including rape, can result in physical trauma, many people who experience sexual assault will not suffer any physical injury.[39] Rape myths suggest that the stereotypical victim of sexual violence is a bruised and battered young woman. The central issue in many cases of rape or other sexual assault is whether or not both parties consented to the sexual activity or whether or not both parties had the capacity to do so. Thus, physical force resulting in visible physical injury is not always seen. This stereotype can be damaging because people who have experienced sexual assault but have no physical trauma may be less inclined to report to the authorities or to seek health care.[40] However, women who experienced rape or physical violence by a partner were more likely than people who had not experienced this violence to report frequent headaches, chronic pain, difficulty sleeping, activity limitation, poor physical health, and poor mental health.[41]

Economic effects

Due to rape or sexual assault, or the threat of, there are many resulting impacts on income and commerce at the macro level. Each sexual assault (excluding child abuse) costs $5,100 in tangible losses (lost productivity, medical and mental health care, police/fire services, and property damage) plus $81,400 in lost quality of life.[42] This issue has been addressed in the Supreme Court. In his dissenting opinion of the U.S. Supreme Court case U.S. v. Morrison, Justice Souter explained that 75% of women never go to the movies alone at night and nearly 50% will not ride public transportation out of fear of rape or sexual assault. It also stated that less than 1% of victims collect damages and 50% of women lose their jobs or quit after the trauma. The court ruled in U.S. v. Morrison that Congress did not have the authority to enact part of the Violence Against Women Act because it did not have a direct impact on commerce. The Commerce Clause of Article I Section VII of the U.S. Constitution gives authority and jurisdiction to the Federal government in matters of interstate commerce. As a result, the victim was unable to sue her attacker in Federal Court.

Sexual assault also has adverse economic effects for survivors on the micro level. For instance, survivors of sexual assault often require time off from work[43] and face increased rates of unemployment.[44] Survivors of rape by an intimate partner lose an average of $69 per day due to unpaid time off from work.[45] Sexual assault is also associated with numerous negative employment consequences, including unpaid time off, diminished work performance, job loss, and inability to work, all of which can lead to lower earnings for survivors.[46]

Medical and psychological treatment of victims

In the emergency room, emergency contraceptive medications are offered to women raped by men because about 5% of such rapes result in pregnancy.[47] Preventative medication against sexually transmitted infections are given to victims of all types of sexual assault (especially for the most common diseases like chlamydia, gonorhea, trichomoniasis and bacterial vaginosis) and a blood serum is collected to test for STIs (such as HIV, hepatitis B and syphilis).[47] Any survivor with abrasions are immunized for tetanus if 5 years have elapsed since the last immunization.[47] Short-term treatment with a benzodiazepine may help with acute anxiety and antidepressants may be helpful for symptoms of PTSD, depression and panic attacks.[47] Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) has also been proposed as a psychiatric treatment for victims of sexual assault.[48] With regard to long term psychological treatment, prolonged exposure therapy has been tested as a method of long-term PTSD treatment for victims of sexual abuse.[49]

Post-assault mistreatment of victims

After the assault, victims may become the target of slut-shaming to cyberbullying. In addition, their credibility may be challenged. During criminal proceedings, publication bans and rape shield laws may operate to protect victims from excessive public scrutiny. Negative social responses to victims’ disclosures of sexual assault have the potential to lead to posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms. Social isolation, following a sexual assault, can result in the victim experiencing a decrease in their self-esteem and likelihood of rejecting unwanted sexual advances in the future.[50]

Prevention

Sexual harassment and assault may be prevented by secondary school,[51] college,[52][53] workplace[54] and public education programs. At least one program for fraternity men produced "sustained behavioral change".[52][55] At least one study showed that creative campaigns with attention grabbing slogans and images that market consent are effective tools to raise awareness of campus sexual assault and related issues.[56]

Several research based rape prevention programs have been tested and verified through scientific studies. The rape prevention programs that have the strongest empirical data in the research literature include the following:

The Men's and Women's Programs, also known as the One in Four programs, were written by John Foubert.[57] and is focused on increasing empathy toward rape survivors and motivating people to intervene as bystanders in sexual assault situations. Published data shows that high-risk persons who saw the Men's and Women's Program committed 40% fewer acts of sexually coercive behavior than those who didn't. They also committed acts of sexual coercion that were 8 times less severe than a control group.[58] Further research also shows that people who saw the Men's and Women's Program reported more efficacy in intervening and greater willingness to help as a bystander after seeing the program.[59] Several additional studies are available documenting its efficacy.[52][60][61]

Bringing in the Bystander was written by Victoria Banyard. Its focus is on who bystanders are, when they have helped, and how to intervene as a bystander in risky situations. The program includes a brief empathy induction component and a pledge to intervene in the future. Several studies show strong evidence of favorable outcomes including increased bystander efficacy, increased willingness to intervene as a bystander, and decreased rape myth acceptance.[62][63][64]

The MVP: Mentors in Violence Prevention was written by Jackson Katz. This program focuses on discussing a male bystander who didn't intervene when woman was in danger. An emphasis is placed on encouraging men to be active bystanders rather than standing by when they notice abuse. The bulk of the presentation is on processing hypothetical scenarios. Outcomes reported in research literature include lower levels of sexism and increased belief that participants could prevent violence against women.[65]

The Green Dot program was written by Dorothy Edwards. This program includes both motivational speeches and peer education focused on bystander intervention. Outcomes show that program participation is associated with reductions in rape myth acceptance and increased bystander intervention.[66]

The city of Edmonton, Canada, initiated a public education campaign aimed at potential perpetrators. Posters in bar bathrooms and public transit centers reminded men that "It's not sex when she's wasted" and "It's not sex when he changes his mind". The campaign was so effective that it spread to other cities. "The number of reported sexual assaults fell by 10 per cent last year in Vancouver, after the ads were featured around the city. It was the first time in several years that there was a drop in sexual assault activity."[67]

President Barack Obama and Vice President Joe Biden introduced in September 2014 a nationwide campaign against sexual assault entitled "It's on us". The campaign includes tips against sexual assault, as well as broad scale of private and public pledges to change to provoke a cultural shift, with a focus on student activism, to achieve awareness and prevention nationwide. UC Berkeley, NCAA and Viacom have publicly announced their partnership.[68]

Prevalence

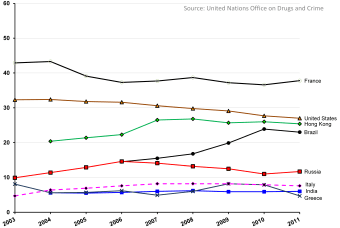

A United Nations report compiled from government sources showed that more than 250,000 cases of rape or attempted rape were recorded by police annually. The reported data covered 65 countries.[69]

United States

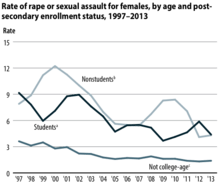

.jpg)

The U.S. Department of Justice's National Crime Victimization Survey states that on average there are 237,868 victims (age 12 or older) of sexual assault and rape each year. According to RAINN, every 107 seconds someone in America is sexually assaulted.[70] Sexual assault in the United States military also is a salient issue. Some researchers assert that the unique professional and socially-contained context of military service can heighten the destructive nature of sexual assault, and, therefore, improved support is needed for these victims.[71]

The victims of sexual assault:

Age

- 15% are under the age of 12

- 29% are age 12–17[70]

- 44% are under age 18

- 80% are under age 30

- 12–34 are the highest risk years

- Girls ages 16–19 are 4 times more likely than the general population to be victims of rape, attempted rape, or sexual assault.[72]

By gender A study from 1998 finds that,

- 88.7% of rape victims are women, the other 11.3% being men

- 17.6% of women have been victims of attempted (2.8%) or completed (14.8%) rape during their lifetime

- 3% of men have been victims of attempted or completed rape during their lifetime

- 17.7 million women have been victims of attempted or completed rape during their lifetime

- 2.78 million men have been victims of attempted or completed rape during their lifetime.[72] [73]

Largely because of child and prison rape, approximately ten percent of reported rape victims are male.[74]

The National Crime Victimization Survey conducted by the U.S. Justice Department (Bureau of Justice Statistics) found that from 1995 to 2013, men represented 17% of victims of sexual assault and rape on college campuses, and 4% of non-campus sexual assaults and rapes.[75]

LGBT

LGBT identifying individuals, with the exception of lesbian women, are more likely to experience sexual assault on college campuses than heterosexual individuals.[76]

- 1 in 8 lesbian women and nearly 50% of bisexual women and men experience sexual assault in their lifetime.

- Nearly 4 in 10 gay men experience sexual violence in their lifetime.

- 64% of transgender people have experienced sexual assault in their lifetime.[77]

Effects

- 3 times more likely to suffer from depression

- 6 times more likely to suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder

- 13 times more likely to abuse alcohol

- 26 times more likely to abuse drugs

- 4 times more likely to contemplate suicide[72]

The reporting of sexual assault:

- on average 68% of sexual assaults go unreported[70]

- 98% of rapists will not spend time in jail

The assailants:

According to the U.S. Department of Justice 1997 Sex Offenses and Offenders Study,

- A rapist's age on average is 31 years old

- 52% of offenders are white

- 22% of rapists imprisoned report that they are married

- Juveniles accounted for 16% of forcible rape arrestees in 1995 and 17% of those arrested for other sex offenses

In 2001,

- 11% of rapes involved the use of a weapon

- 3% used a gun

- 6% used a knife

- 2% used another form of weapon

- 84% of victims reported the use of physical force only[78]

According to the U.S. Department of Justice 2005 National Crime Victimization Study

- About 2/3 of rapes were committed by someone known to the victim

- 73% of sexual assaults were perpetrated by a non-stranger

- 38% of rapists are a friend or acquaintance

- 28% are an intimate partner

- 7% are a relative[78]

College

In the United States, several studies since 1987 have indicated that one in four college women have experienced rape or attempted rape at some point in their lifetime. These studies are based on anonymous surveys of college women, not reports to the police, and the results are disputed.[79]

In 2015, Texas A&M University professor Jason Lindo and his colleagues analyzed over two decades worth of FBI data, noting that reports of rape increased 15-57% around the times of major American Football games at Division 1 schools while attempting to find a link between campus rape and alcohol.[80]

A 2006 report from the U.S. Department of Justice titled "The Sexual Victimization of College Women" reports that 3.1% of undergraduates survived rape or attempted rape during a 6–7 month academic year with an additional 10.1% surviving rape prior to college and an additional 10.9% surviving attempted rape prior to college. With no overlap between these groups, these percentages add to 24.1%, or "One in Four".[81]

Koss, Gidycz & Wisniewski published a study in 1987 where they interviewed approximately 6,000 college students on 32 college campuses nationwide. They asked several questions covering a wide range of behaviors. From this study 15% of college women answered "yes" to questions about whether they experienced something that met the definition of rape. An additional 12% of women answered "yes" to questions about whether they experienced something that met the definition of attempted rape, thus the statistic One in Four.[82]

A point of contention lies in the leading nature of the questions in the study conducted by Koss, Gidycz & Wisniewski. Koss herself later admitted that the question that had garnered the largest "rape" result was flawed and ultimately rendered the study invalid. Most prominently the problem was that many respondents who had answered yes to several questions had their responses treated as having been raped. The issue being that these same respondents did not feel they had been victimized and never sought redress for grievances. The resultant change shows a prevalence of only 1 in 22 college women having been raped or attempted to be raped during their time at college.[79]

In 1995, the CDC replicated part of this study, however they examined rape only, and did not look at attempted rape. They used a two-stage cluster sample design to produce a nationally representative sample of undergraduate college students aged greater than or equal to 18 years. The first-stage sampling frame contained 2,919 primary sampling units (PSUs), consisting of 2- and 4-year colleges and universities. The second sampling stage consisted of a random sample drawn from the primary sample unit frame enrolled in the 136 participating colleges and universities to increase the sample size to 4,609 undergraduate college students aged greater than or equal to 18 years old with a representative sample demographic matching the national demographic. Differential sampling rates of the PSU were used to ensure sufficient numbers of male and female, black and Hispanic students in the total sample population. After differential sample weighting, female students represented 55.5% of the sample; white students represented 72.8% of the sample, black students 10.3%, Hispanic students 7.1%, and 9.9% were other.[83] It was determined that nationwide, 13.1% of college students reported that they had been forced to have sexual intercourse against their will during their lifetime. Female students were significantly more likely than male students to report they had ever been forced to have sexual intercourse; 20% of approximately 2500 females (55% of 4,609 samples) and 3.9% of males reported experiencing rape thus far in the course of their lifetime.[84]

Other studies concerning the annual incidence of rape, some studies conclude an occurrence of 5%. The National Survey of Children's Exposure to Violence found that in the 2013–2014 academic year, 4.6% of girls ages 14 – 17 experienced sexual assault or sexual abuse.[85] In another study, Mohler-Kuo, Dowdall, Koss & Weschler (2004)[86] found in a study of approximately 25,000 college women nationwide that 4.7% experienced rape or attempted rape during a single academic year. This study did not measure lifetime incidence of rape or attempted rape. Similarly, Kilpatrick, Resnick, Ruggiero, Conoscenti, & McCauley (2007) found in a study of 2,000 college women nationwide that 5.2% experienced rape every year.[87]

On campuses, it has been found that alcohol is a prevalent issue in regards to sexual assault. It has been estimated that 1 in 5 women experience an assault and of those women 50%-75% have had either the attacker, the woman, or both consuming alcohol prior to the assault.[88] Not only has it been a factor in the rates for sexual assault on campus, but because of the prevalence, assaults are also being affected specifically by the inability to give consent when intoxicated and bystanders not knowing when to intervene due to their own intoxication or the intoxication of the victim.[88][89]

Children

Other research has found that about 80,000 American children are sexually abused each year.[90]

By jurisdiction

Australia

Within Australia, the term sexual assault is used to describe a variation of sexual offences. This is due to a variety of definitions and use of terminology to describe sexual offences within territories and states as each territory and state have their own legislation to define rape, attempted rape, sexual assault, aggravated sexual assault, sexual penetration or intercourse without consent and sexual violence.

In the State of New South Wales, sexual assault is a statutory offence punishable under s 61I of the Crimes Act 1900. The term "sexual assault" is equivalent to "rape" in ordinary parlance, while all other assaults of a sexual nature are termed "indecent assault".

To be liable for punishment under the Crimes Act 1900, an offender must intend to commit an act of sexual intercourse as defined under s 61H(1) while having one of the states of knowledge of non-consent defined under s 61HA(3). But note that s 61HA(3) is an objective standard which only require the person has no reasonable grounds for believing the other person is consenting.[91] The maximum penalty for sexual assault is 14 years imprisonment.[92]

Aggravated sexual assault is sexual intercourse with another person without the consent of the other person and in circumstances of aggravation. The maximum penalty is imprisonment for 20 years under s 61J of the Crimes Act.

In the state of Victoria, rape is punishable under s 38 of the Crimes Act 1958, with a maximum penalty of 25 years imprisonment.[93]

In the state of South Australia, rape is punishable under s 48 of the Criminal Law Consolidation Act 1935 (SA) with a maximum term of life imprisonment.[94]

In the state of Western Australia, sexual penetration is punishable under s 325 the Criminal Code Act 1913 with a maximum sentence of 14 years imprisonment.[95]

In the Northern Territory, offences of sexual intercourse and gross indecency without consent are punishable under s 192 of the Criminal Code Act 1983 and punishable with a maximum sentence of life imprisonment.[96]

In Queensland, rape and sexual assault are punishable under s 349, Chapter 32 of the Criminal Code Act 1899 with a maximum penalty of life imprisonment.[97]

In Tasmania, rape is punishable under s 185 of the Criminal Code Act 1924 with a maximum punishment of 21 years under s389 of the Criminal Code Act 1924.[98]

In the Australian Capital Territory, sexual assault is punishable under Part 3 of the Crimes Act 1900 with a maximum punishment of 17 years.[99]

Sexual assault is considered a gendered crime which results in 85% of sexual assaults never coming to the attention of the criminal justice system according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics.[100] This is due to low reporting rates, treatment of victims and distrust of the criminal justice system, difficulty in obtaining evidence and the belief in sexual assault myths.[101]

However, once a person is charged, the public prosecutor will decide whether the case will proceed to trial based on whether there is sufficient evidence and whether a case is in the public interest.[102] Once the matter has reached trial, the matter will generally be heard in the District Court. This is because sexually violent crimes are mostly categorised as indictable offences (serious offences), as opposed to summary offences (minor offences). Sexual offences can also be heard in the Supreme Court, but more generally if the matter is being heard as an appeal.

Once the matter is being heard, the prosecution must provide evidence which proves "beyond reasonable doubt" that the offence was committed by the defendant. The standard of proof is vital in checking the power of the State.[103] While as previously stated that each jurisdiction (State and Territory) has its own sexual offence legislation, there are many common elements to any criminal offence that advise on how the offence is defined and what must be proven by the prosecution in order to find the defendant guilty.[103] These elements are known as Actus Reus which comprises the physical element (see Ryan v Regina [1967])[104] and the Mens Rea which comprises the mental element (see He Kaw Teh (1985)).[105]

Notable sexual assault cases which have resulted in convictions are Regina v Bilal Skaf [2005][106] and Regina v Mohommed Skaf [2005][107] which were highly visible in New South Wales within the media the 2000s. These cases were closely watched by the media and led to legislative changes such as the passing of the Crimes Amendment (Aggravated Sexual Assault in Company) Act 2001 No 62[108] which dramatically increased the sentences for ‘gang rapists’ by creating a new category of crime known as Aggravated Sexual Assault in Company. Changes were also made to the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act 1999.[109] This change is known as the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Amendment (Victim Impact Statements) Act 2004 No 3[110] which expands the category of offences in respect of which a Local Court may receive and consider Victim Impact Statements to include some indictable offences which are usually dealt with summarily.

Canada

Sexual assault is defined as sexual contact with another person without that other person's consent. Consent is defined in section 273.1(1) as "the voluntary agreement of the complainant to engage in the sexual activity in question".

Section 265 of the Criminal Code defines the offences of assault and sexual assault.

Section 271 criminalizes "Sexual assault", section 272 criminalizes "Sexual assault with a weapon, threats to a third party or causing bodily harm" and section 273 criminalizes "Aggravated sexual assault".

Consent

The absence of consent defines the crime of sexual assault. Section 273.1 (1) defines consent, section 273.1 (2) outlines certain circumstances where "no consent" is obtained, while section 273.1 (3) states that subsection (2) does not limit the circumstances where "no consent" is obtained (i.e. subsection (2) describes some circumstances which deem the act to be non-consensual, but other circumstances, not described in this section, can also deem the act as having been committed without consent). "No consent" to sexual assault is also subject to Section 265 (3), which also outlines several situations where the act is deemed non-consensual. In 2011, the Supreme Court of Canada in R. v. J.A. interpreted the provisions below to find that a person must have an active mind during the sexual activity in order to consent, and that they cannot give consent in advance.[111][112]

- Meaning of "consent"

273.1 (1) Subject to subsection (2) and subsection 265(3), "consent" means, for the purposes of sections 271, 272 and 273, the voluntary agreement of the complainant to engage in the sexual activity in question.

Where no consent obtained

(2) No consent is obtained, for the purposes of sections 271, 272 and 273, where (a) the agreement is expressed by the words or conduct of a person other than the complainant; (b) the complainant is incapable of consenting to the activity; (c) the accused induces the complainant to engage in the activity by abusing a position of trust, power or authority; (d) the complainant expresses, by words or conduct, a lack of agreement to engage in the activity; or (e) the complainant, having consented to engage in sexual activity, expresses, by words or conduct, a lack of agreement to continue to engage in the activity.

Subsection (2) not limiting

(3) Nothing in subsection (2) shall be construed as limiting the circumstances in which no consent is obtained.

- Section 265(3)

Consent

(3) For the purposes of this section, no consent is obtained where the complainant submits or does not resist by reason of (a) the application of force to the complainant or to a person other than the complainant; (b) threats or fear of the application of force to the complainant or to a person other than the complainant; (c) fraud; or (d) the exercise of authority.

In accordance with 265 (4) an accused may use the defence that he or she believed that the complainant consented, but such a defence may be used only when "a judge, if satisfied that there is sufficient evidence and that, if believed by the jury, the evidence would constitute a defence, shall instruct the jury when reviewing all the evidence relating to the determination of the honesty of the accused's belief, to consider the presence or absence of reasonable grounds for that belief"; furthermore according to section 273.2(b) the accused must show that he or she took reasonable steps in order to ascertain the complainant's consent, also 273.2(a) states that if the accused's belief steams from self-induced intoxication, or recklessness or wilful blindness than such belief is not a defence.[111]

- 265 (4)

Accused’s belief as to consent

(4) Where an accused alleges that he or she believed that the complainant consented to the conduct that is the subject-matter of the charge, a judge, if satisfied that there is sufficient evidence and that, if believed by the jury, the evidence would constitute a defence, shall instruct the jury, when reviewing all the evidence relating to the determination of the honesty of the accused's belief, to consider the presence or absence of reasonable grounds for that belief.

- Where belief in consent not a defence

273.2 It is not a defence to a charge under section 271, 272 or 273 that the accused believed that the complainant consented to the activity that forms the subject-matter of the charge, where (a) the accused's belief arose from the accused's

(i) self-induced intoxication, or

(ii) recklessness or wilful blindness; or (b) the accused did not take reasonable steps, in the circumstances known to the accused at the time, to ascertain that the complainant was consenting.

Supreme Court partial interpretation of "consent"

The Supreme Court of Newfoundland and Labrador jury ruled in favour of a defense that added to the interpretation of the consent laws.[113] The defenses stated and the Jury was reminded by Justice Valerie Marshall:[114]

- because a complainant is drunk does not diminish their capacity to consent.

- because a complainant cannot remember if they gave consent does not mean they could not have consented.[115]

The coined phrase regarding this defense was "Moral vs. legal consent"[116]

Germany

Before 1997, the definition of rape was: "Whoever compels a woman to have extramarital intercourse with him, or with a third person, by force or the threat of present danger to life or limb, shall be punished by not less than two years’ imprisonment."[117]

In 1997, a broader definition was adopted with the 13th criminal amendment, section 177–179, which deals with sexual abuse.[118] Rape is generally reported to the police, although it is also allowed to be reported to the prosecutor or District Court.[118]

The Strafgesetzbuch reads:[119]

- Section 177

- Sexual assault by use of force or threats; rape

- Whosoever coerces another person

- by force;

- by threat of imminent danger to life or limb; or

- by exploiting a situation in which the victim is unprotected and at the mercy of the offender,

- to suffer sexual acts by the offender or a third person on their own person or to engage actively in sexual activity with the offender or a third person, shall be liable to imprisonment of not less than one year.

- In especially serious cases the penalty shall be imprisonment of not less than two years. An especially serious case typically occurs if

- the offender performs sexual intercourse with the victim or performs similar sexual acts with the victim, or allows them to be performed on himself by the victim, especially if they degrade the victim or if they entail penetration of the body (rape); or

- the offence is committed jointly by more than one person.

Subsections (3), (4) and (5) provide additional stipulations on sentencing depending on aggravating or mitigating circumstances.

Section 178 provides that "If the offender through sexual assault or rape (section 177) causes the death of the victim at least by gross negligence the penalty shall be imprisonment for life or not less than ten years."

Republic of Ireland

As in many other jurisdictions, the term sexual assault is generally used to describe non-penetrative sexual offences. Section 2 of the Criminal Law (Rape) Act of 1981 states that a man has committed rape if he has sexual intercourse with a woman who at the time of the intercourse does not consent to it, and at that time he knows that she does not consent to the intercourse or he is reckless as to whether she does or does not consent to it. Under Section 4 of the Criminal Law (Rape Amendment) Act of 1990, rape means a sexual assault that includes penetration (however slight) of the anus or mouth by the penis or penetration (however slight) of the vagina by any object held or manipulated by another person. The maximum penalty for rape in Ireland is imprisonment for life.[120]

South Africa

The Criminal Law (Sexual Offences and Related Matters) Amendment Act created the offence of sexual assault, replacing a common-law offence of indecent assault. "Sexual assault" is defined as the unlawful and intentional sexual violation of another person without their consent. The Act's definition of "sexual violation" incorporates a number of sexual acts, including any genital contact that does not amount to penetration as well as any contact with the mouth designed to cause sexual arousal. Non-consensual acts that involve actual penetration are rape rather than sexual assault.

Unlawfully and intentionally inspiring the belief in another person that they will be sexually violated also amounts to sexual assault. The Act also created the offences of "compelled sexual assault", when a person forces a second person to commit an act of sexual violation with a third person; and "compelled self-sexual assault", when a person forces another person to masturbate or commit various other sexual acts on theirself.[121]

United Kingdom

England and Wales

Sexual assault is a statutory offence in England and Wales. It is created by section 3 of the Sexual Offences Act 2003 which defines "sexual assault" as when a person (A)

- intentionally touches another person (B),

- the touching is sexual,

- B does not consent to the touching, and

- A does not reasonably believe that B consents.

Whether a belief is reasonable is to be determined having regard to all the circumstances, including any steps A has taken to ascertain whether B consents.

Sections 75 and 76 apply to an offence under this section.

A person guilty of an offence under this section is liable—

- on summary conviction, to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 6 months or a fine not exceeding the statutory maximum or both;

- on conviction on indictment, to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 10 years.[122]

Consent

Section 74 of the Sexual Offenses Act explains that "a person consents if he agrees by choice and has the freedom and capacity to make that choice".

Section 75 clarifies what consent means

75 Evidential presumptions about consent

(1)If in proceedings for an offence to which this section applies it is proved— (a)that the defendant did the relevant act, (b)that any of the circumstances specified in subsection (2) existed, and (c)that the defendant knew that those circumstances existed, the complainant is to be taken not to have consented to the relevant act unless sufficient evidence is adduced to raise an issue as to whether he consented, and the defendant is to be taken not to have reasonably believed that the complainant consented unless sufficient evidence is adduced to raise an issue as to whether he reasonably believed it.

(2)The circumstances are that— (a)any person was, at the time of the relevant act or immediately before it began, using violence against the complainant or causing the complainant to fear that immediate violence would be used against him; (b)any person was, at the time of the relevant act or immediately before it began, causing the complainant to fear that violence was being used, or that immediate violence would be used, against another person; (c)the complainant was, and the defendant was not, unlawfully detained at the time of the relevant act; (d)the complainant was asleep or otherwise unconscious at the time of the relevant act; (e)because of the complainant's physical disability, the complainant would not have been able at the time of the relevant act to communicate to the defendant whether the complainant consented; (f)any person had administered to or caused to be taken by the complainant, without the complainant's consent, a substance which, having regard to when it was administered or taken, was capable of causing or enabling the complainant to be stupefied or overpowered at the time of the relevant act.

(3)In subsection (2)(a) and (b), the reference to the time immediately before the relevant act began is, in the case of an act which is one of a continuous series of sexual activities, a reference to the time immediately before the first sexual activity began.

Northern Ireland

Sexual assault is a statutory offence. It is created by article 7 of the Sexual Offences (Northern Ireland) Order 2008. Sexual assault is defined as follows:[123]

- Sexual assault

- (1) A person (A) commits an offence if—

- (a) he intentionally touches another person (B),

- (b) the touching is sexual,

- (c) B does not consent to the touching, and

- (d) A does not reasonably believe that B consents.

Scotland

Sexual assault is a statutory offence. It is created by section 3 of the Sexual Offences (Scotland) Act 2009. Sexual assault is defined as follows:[124]

- Sexual assault

- (1) If a person ("A")—

- (a) without another person ("B") consenting, and

- (b) without any reasonable belief that B consents,

- does any of the things mentioned in subsection (2), then A commits an offence, to be known as the offence of sexual assault.

- (2) Those things are, that A—

- (a) penetrates sexually, by any means and to any extent, either intending to do so or reckless as to whether there is penetration, the vagina, anus or mouth of B,

- (b) intentionally or recklessly touches B sexually,

- (c) engages in any other form of sexual activity in which A, intentionally or recklessly, has physical contact (whether bodily contact or contact by means of an implement and whether or not through clothing) with B,

- (d) intentionally or recklessly ejaculates semen onto B,

- (e) intentionally or recklessly emits urine or saliva onto B sexually.

United States

The United States Department of Justice defines sexual assault as "any type of sexual contact or behavior that occurs without the explicit consent of the recipient. Falling under the definition of sexual assault are sexual activities as forced sexual intercourse, forcible sodomy, child molestation, incest, fondling, and attempted rape."[125]

Every U.S. state has its own code of laws, and thus the definition of conduct that constitutes a crime, including a sexual assault, may vary to some degree by state.[126][127] Some states may refer to sexual assault as "sexual battery" or "criminal sexual conduct".[128]

Texas

The Texas Penal Code, Sec. 22.011(a)[129] defines sexual assault as

A person commits [sexual assault] if the person:

- (1) intentionally or knowingly:

- (A) causes the penetration of the anus or sexual organ of another person by any means, without that person's consent;

- (B) causes the penetration of the mouth of another person by the sexual organ of the actor, without that person's consent; or

- (C) causes the sexual organ of another person, without that person's consent, to contact or penetrate the mouth, anus, or sexual organ of another person, including the actor; or

- (2) intentionally or knowingly:

- (A) causes the penetration of the anus or sexual organ of a child by any means;

- (B) causes the penetration of the mouth of a child by the sexual organ of the actor;

- (C) causes the sexual organ of a child to contact or penetrate the mouth, anus, or sexual organ of another person, including the actor;

- (D) causes the anus of a child to contact the mouth, anus, or sexual organ of another person, including the actor; or

- (E) causes the mouth of a child to contact the anus or sexual organ of another person, including the actor.

See also

- Abuse

- List of the causes of genital pain

- List of anti-sexual assault organizations in the United States

- #MeToo

- National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children

- Patient abuse

- Post-assault treatment of sexual assault victims

- R v Collins

- Raelyn Campbell

- Rape kit

- Sexual assault in the U.S. military

- Sexual assault of migrants from Latin America to the United States

- Sexual violence

- Statutory rape

References

- Peter Cameron, George Jelinek, Anne-Maree Kelly, Anthony F. T. Brown, Mark Little (2011). Textbook of Adult Emergency Medicine E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 658. ISBN 978-0702049316. Retrieved 30 December 2017.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Sexual Assault Fact Sheet" (PDF). Office on Women's Health. Department of Health & Human Services. 21 May 2015. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- Assault, Black's Law Dictionary, 8th Edition. See also Ibbs v The Queen, High Court of Australia, 61 ALJR 525, 1987 WL 714908 (sexual assault defined as sexual penetration without consent); Sexual Offences Act 2003 Chapter 42 s 3 Sexual assault (United Kingdom), (sexual assault defined as sexual contact without consent), and Chase v. R. 1987 CarswellNB 25 (Supreme Court of Canada) (sexual assault defined as force without consent of a sexual nature)

- "Sexual Assault". Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- "The National Center for Victims of Crime – Library/Document Viewer". Ncvc.org. Archived from the original on 20 July 2012. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- "Child Sexual Abuse". Medline Plus. U.S. National Library of Medicine. 2 April 2008. Archived from the original on 5 December 2013.

- "Guidelines for psychological evaluations in child protection matters". American Psychologist. 54 (8): 586–93. 1999. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.54.8.586. PMID 10453704. Lay summary – APA PsycNET (7 May 2008).

Abuse, sexual (child): generally defined as contacts between a child and an adult or other person significantly older or in a position of power or control over the child, where the child is being used for sexual stimulation of the adult or other person

- Martin, Judy; Anderson, Jessie; Romans, Sarah; Mullen, Paul; O'Shea, Martine (1993). "Asking about child sexual abuse: Methodological implications of a two stage survey". Child Abuse & Neglect. 17 (3): 383–92. doi:10.1016/0145-2134(93)90061-9. PMID 8330225.

- "Child sexual abuse definition from". the NSPCC. Archived from the original on 7 February 2012. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- Brown, Rick; Napier, Sarah; Smith, Russell G (2020), Australians who view live streaming of child sexual abuse: An analysis of financial transactions, Australian Institute of Criminology, ISBN 9781925304336 pp. 1–4.

- Roosa, MW; Reinholtz, C; Angelini, PJ (1999). "The relation of child sexual abuse and depression in young women: Comparisons across four ethnic groups". Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 27 (1): 65–76. PMID 10197407.

- Widom, CS (1999). "Posttraumatic stress disorder in abused and neglected children grown up". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 156 (8): 1223–9. doi:10.1176/ajp.156.8.1223 (inactive 29 May 2020). PMID 10450264.

- Levitan, Robert D.; Rector, Neil A.; Sheldon, Tess; Goering, Paula (2003). "Childhood adversities associated with major depression and/or anxiety disorders in a community sample of Ontario: Issues of co-morbidity and specificity". Depression and Anxiety. 17 (1): 34–42. doi:10.1002/da.10077. PMID 12577276.

- Messman-Moore, T. L.; Long, P. J. (2000). "Child Sexual Abuse and Revictimization in the Form of Adult Sexual Abuse, Adult Physical Abuse, and Adult Psychological Maltreatment". Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 15 (5): 489–502. doi:10.1177/088626000015005003.

- Teitelman AM, Bellamy SL, Jemmott JB 3rd, Icard L, O'Leary A, Ali S, Ngwane Z, Makiwane M. Childhood sexual abuse and sociodemographic factors prospectively associated with intimate partner violence perpetration among South African heterosexual men. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2017;51(2):170-178

- Dinwiddie, S.; Heath, A. C.; Dunne, M. P.; Bucholz, K. K.; Madden, P. A. F.; Slutske, W. S.; Bierut, L. J.; Statham, D. B.; Martin, N. G. (2000). "Early sexual abuse and lifetime psychopathology: A co-twin–control study". Psychological Medicine. 30 (1): 41–52. doi:10.1017/S0033291799001373. PMID 10722174.

- Courtois, Christine A. (1988). Healing the Incest Wound: Adult Survivors in Therapy. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 208. ISBN 978-0-393-31356-7.

- Julia Whealin (22 May 2007). "Child Sexual Abuse". National Center for Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, US Department of Veterans Affairs. Archived from the original on 30 July 2009.

- David Finkelhor (Summer–Fall 1994). "Current Information on the Scope and Nature of Child Sexual Abuse" (PDF). The Future of Children. (1994) 4(2): 31–53. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 October 2008.

- "Crimes against Children Research Center". Unh.edu. Archived from the original on 23 August 2013. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- "Family Research Laboratory". Unh.edu. Archived from the original on 26 November 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- Gorey, Kevin M.; Leslie, Donald R. (1997). "The prevalence of child sexual abuse: Integrative review adjustment for potential response and measurement biases". Child Abuse & Neglect. 21 (4): 391–8. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.465.1057. doi:10.1016/S0145-2134(96)00180-9. PMID 9134267.

- "Adult Manifestations of Childhood Sexual Abuse". www.aaets.org. American Academy of Experts in Traumatic Stress. Archived from the original on 3 April 2018. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- "About Sexual Violence". Pcar.org. Archived from the original on 20 October 2014. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- "2010 Georgia Code :: TITLE 16 - CRIMES AND OFFENSES :: CHAPTER 6 - SEXUAL OFFENSES :: § 16-6-5.1 - Sexual assault by persons with supervisory or disciplinary authority; sexual assault by practitioner of psychotherapy against patient; consent not a defense; penalty upon conviction for sexual assault". Justia Law. Archived from the original on 4 September 2017. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "Sexual Violence". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20141019130818/http://www.pcar.org/elder-sexual-abuse

- Roberts, Albert R.; Ann Wolbert Bergess; CHERYL REGEHR (2009). Victimology: Theories and Applications. Sudbury, Mass: Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 228. ISBN 978-0-7637-7210-9.

- Krantz, G.; Garcia-Moreno, C (2005). "Violence against women". Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 59 (10): 818–21. doi:10.1136/jech.2004.022756. PMC 1732916. PMID 16166351.

- "Sapphire". Metropolitan Police Service. Archived from the original on 6 December 2012. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- Abbey, Antonia; Beshears, Renee; Clinton-Sherrod, A. Monique; McAuslan, Pam (2004). "Similarities and Differences in Women's Sexual Assault Experiences Based on Tactics Used by the Perpetrator". Psychology of Women Quarterly. 28 (4): 323–32. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2004.00149.x. PMC 4527559. PMID 26257466.

- Kaufman, A; Divasto, P; Jackson, R; Voorhees, D; Christy, J (1980). "Male rape victims: Noninstitutionalized assault". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 137 (2): 221–3. doi:10.1176/ajp.137.2.221. PMID 7352580.

- Tjaden, Patricia; Thoennes, Nancy. "Prevalence, Incidence, and Consequences of Violence Against Women: Findings From the National Violence Against Women Survey Control and Prevention" (PDF). National Criminal Justice Reference Service. National Institute of Justice Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

rape is a crime committed primarily against youth: 18 percent of women surveyed said they experienced a completed or attempted rape at some time in their life and 0.3 percent said they experienced a completed or attempted rape in the previous 12 months. Of the women who reported being raped at some time in their lives, 22 percent were under 12 years old and 32 percent were 12 to 17 years old when they were first raped.

- YING HUI TAN, Barrister (12 January 1993). "Law Report: Attempted rape came within definition of 'sexual offence': Regina v Robinson – Court of Appeal (Criminal Divisional) (Lord Taylor of Gosforth, Lord Chief Justice, Mr Justice Potts and Mr Justice Judge), 27 November 1992". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 21 February 2010. Retrieved 27 October 2010.

- The Age, 3 June 2019, One in three women victim to 'stealth' condom removal

- Paludi, Michele Antoinette; Barickman (1991). Academic and Workplace Sexual Harassment. SUNY Press. pp. 2–5. ISBN 978-0-7914-0829-2.

- Dziech et al. 1990, Boland 2002

- "Facts About Sexual Harassment". U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. 27 June 2002. Archived from the original on 11 July 2017. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- Kennedy KM, Heterogeneity of existing research relating to sexual violence, sexual assault and rape precludes meta-analysis of injury data. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine. (2013), 20(5):447–459

- Kennedy KM, The relationship of victim injury to the progression of sexual crimes through the criminal justice system, Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine 2012:19(6):309-311

- Mandi, Dupain (2014). "Developing and Implementing a Sexual Assault Violence Prevention and Awareness Campaign at a State-Supported Regional University". American Journal of Health Studies. 29 (4): 264.

- Miller, Cohen, & Weirsema (1996). "Victim Costs and Consequences: A New Look" (PDF). National Institute of Justice. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 May 2016. Retrieved 1 September 2016.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Tjaden & Thoennes (2006). "Extent, Nature, and Consequences of Rape Victimization: Findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey". National Institute of Justice. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs. Archived from the original on 16 September 2016. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- Byrne, Christina A.; Resnick, Heidi S.; Kilpatrick, Dean G.; Best, Connie L.; Saunders, Benjamin E. (1999). "The socioeconomic impact of interpersonal violence on women". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 67 (3): 362–366. doi:10.1037/0022-006x.67.3.362.

- Chrisler, Joan C.; Ferguson, Sheila (1 November 2006). "Violence against Women as a Public Health Issue". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1087 (1): 235–249. Bibcode:2006NYASA1087..235C. doi:10.1196/annals.1385.009. ISSN 1749-6632. PMID 17189508.

- Loya, Rebecca M. (1 October 2015). "Rape as an Economic Crime The Impact of Sexual Violence on Survivors' Employment and Economic Well-Being". Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 30 (16): 2793–2813. doi:10.1177/0886260514554291. ISSN 0886-2605. PMID 25381269.

- Varcarolis, Elizabeth (2013). Essentials of psychiatric mental health nursing. St. Louis: Elsevier. pp. 439–442.

- Posmontier, B; Dovydaitis, T; Lipman, K (2010). "Sexual violence: psychiatric healing with eye movement reprocessing and desensitization". Health Care for Women International. 31 (8): 755–68. doi:10.1080/07399331003725523. PMC 3125707. PMID 20623397.

- Schiff, M; Nacasch, N; Levit, S; Katz, N; Foa, EB (2015). "Prolonged exposure for treating PTSD among female methadone patients who were survivors of sexual abuse in Israel". Social Work & Health Care. 54 (8): 687–707. doi:10.1080/00981389.2015.1058311. PMID 26399489.

- Relyea, M.; Ullman, S. E. (2013). "Unsupported or Turned Against". Psychology of Women Quarterly. 39 (1): 37–52. doi:10.1177/0361684313512610. PMC 4349407. PMID 25750475.

- Smothers, Melissa Kraemer; Smothers, D. Brian (2011). "A Sexual Assault Primary Prevention Model with Diverse Urban Youth". Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 20 (6): 708–27. doi:10.1080/10538712.2011.622355. PMID 22126112.

- Foubert, John D. (2000). "The Longitudinal Effects of a Rape-prevention Program on Fraternity Men's Attitudes, Behavioral Intent, and Behavior". Journal of American College Health. 48 (4): 158–63. doi:10.1080/07448480009595691. PMID 10650733.

- Vladutiu, C. J.; Martin, S. L.; Macy, R. J. (2010). "College- or University-Based Sexual Assault Prevention Programs: A Review of Program Outcomes, Characteristics, and Recommendations". Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 12 (2): 67–86. doi:10.1177/1524838010390708. PMID 21196436.

- Yeater, E; O'Donohue, W (1999). "Sexual assault prevention programs Current issues, future directions, and the potential efficacy of interventions with women". Clinical Psychology Review. 19 (7): 739–71. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.404.3130. doi:10.1016/S0272-7358(98)00075-0. PMID 10520434.

- Garrity, Stacy E. (2011). "Sexual assault prevention programs for college-aged men: A critical evaluation". Journal of Forensic Nursing. 7 (1): 40–8. doi:10.1111/j.1939-3938.2010.01094.x. PMID 21348933.

- Thomas, KA; Sorenson, SB; Joshi, M (2016). ""Consent is good, joyous, sexy": A banner campaign to market consent to college students". Journal of American College Health. 64 (8): 639–650. doi:10.1080/07448481.2016.1217869. PMID 27471816.

- Foubert, John (2011). The Men's and Women's Programs: Ending Rape Through Peer Education. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-88105-0.

- Foubert, John D.; Newberry, Johnathan T; Tatum, Jerry (2008). "Behavior Differences Seven Months Later: Effects of a Rape Prevention Program". Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice. 44 (4). doi:10.2202/1949-6605.1866.

- Langhinrichsen-Rohling, J.; Foubert, J. D.; Brasfield, H. M.; Hill, B.; Shelley-Tremblay, S. (2011). "The Men's Program: Does It Impact College Men's Self-Reported Bystander Efficacy and Willingness to Intervene?". Violence Against Women. 17 (6): 743–59. doi:10.1177/1077801211409728. PMID 21571743.

- Foubert, J. D.; Godin, E. E.; Tatum, J. L. (2009). "In Their Own Words: Sophomore College Men Describe Attitude and Behavior Changes Resulting from a Rape Prevention Program 2 Years After Their Participation". Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 25 (12): 2237–57. doi:10.1177/0886260509354881. PMID 20040715.

- Foubert, John D.; Cremedy, Brandynne J. (2007). "Reactions of Men of Color to a Commonly Used Rape Prevention Program: Attitude and Predicted Behavior Changes". Sex Roles. 57 (1–2): 137–44. doi:10.1007/s11199-007-9216-2.

- Banyard, Moynihan & Plante, 2007

- Banyard, Plante & Moynihan, 2004

- Banyard, Ward, Cohn, Plante, Moorhead, & Walsh, 2007

- Cissner, 2009

- Coker, Cook-Craig, Williams, Fisher, Clear, Garcia & Hegge, 2011

- "Edmonton Sexual Assault Awareness Campaign: 'Don't Be That Guy' So Effective City Relaunches With New Posters (PHOTOS)". Huffingtonpost.ca. December 2012. Archived from the original on 2 September 2016. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- Abbott, Katy (20 September 2014). "White House announces college-campus sexual assault awareness campaign". Reuters. Archived from the original on 21 September 2014. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- The Eighth United Nations Survey on Crime Trends and the Operations of Criminal Justice Systems (2001–2002) Archived 21 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine – Table 02.08 Total recorded rapes, Unodc.org

- "Statistics | RAINN | Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network". rainn.org. Archived from the original on 20 November 2015. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

- Dichter ME, Wagner C, True G. Women veterans' experiences of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual assault in the context of military service: implications for supporting women's health and well-being. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2016 Sep 20. [Epub ahead of print]

- "Who are the Victims? - RAINN - Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network". Rainn.org. Archived from the original on 6 June 2016. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- Tjaden, Patricia; Thoennes, Nancy (November 1998). "Prevalence, Incidence and Consequences of Violence Against Women Survey". National Institute of Justice & Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. Archived from the original on 19 February 2013.

- cf. U.S. Department of Justice. 2003 National Crime Victimization Survey. 2003.

- Fedina, Lisa; Holmes, Jennifer Lynne; Backes, Bethany L. (2016). "Campus Sexual Assault: A Systematic Review of Prevalence Research From 2000 to 2015". Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 19 (1): 76–93. doi:10.1177/1524838016631129. PMID 26906086.

- "College Student Health Survey Report : 2007–2011" (PDF). Bhs.umn.edu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 October 2016. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- "The Offenders - RAINN - Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network". Rainn.org. Archived from the original on 28 May 2016. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 9 December 2012. Retrieved 9 December 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Paquette, Danielle. "The disturbing truth about college football and rape". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 25 August 2016.

- Fisher, Cullen & Turner, 2006

- Koss, Mary P.; Gidycz, Christine A.; Wisniewski, Nadine (1987). "The scope of rape: Incidence and prevalence of sexual aggression and victimization in a national sample of higher education students". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 55 (2): 162–70. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.55.2.162. PMID 3494755.

- "Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance: National College Health Risk Behavior Survey -- United States, 1995". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 14 November 1997. Archived from the original on 19 June 2017.

- Douglas, Kathy A.; Collins, Janet L.; Warren, Charles; Kann, Laura; Gold, Robert; Clayton, Sonia; Ross, James G.; Kolbe, Lloyd J. (1997). "Results from the 1995 National College Health Risk Behavior Survey". Journal of American College Health. 46 (2): 55–66. doi:10.1080/07448489709595589. PMID 9276349.

- Finkelhor, David (June 2015). "Prevalence of Childhood Exposure to Violence, Crime, and Abuse: Results From the National Survey of Children's Exposure to Violence". JAMA Pediatrics. 169 (8): 746–54. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0676. PMID 26121291.

- Mohler-Kuo, M; Dowdall, GW; Koss, MP; Wechsler, H (2004). "Correlates of rape while intoxicated in a national sample of college women". Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 65 (1): 37–45. doi:10.15288/jsa.2004.65.37. PMID 15000502.

- Kilpatrick, Dean; Resnick, Heidi; Ruggiero, Kenneth; Conoscenti, Lauren M.; McCauley, Jenna (July 2007). Drug Facilitated, Incapacitated, and Forcible Rape: A National Study. U.S. Department of Justice. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- Pugh, Brandie; Ningard, Holly; Ven, Thomas Vander; Butler, Leah (2016). "Victim Ambiguity: Bystander Intervention and Sexual Assault in the College Drinking Scene". Deviant Behavior. 37 (4): 401–418. doi:10.1080/01639625.2015.1026777.

- Pugh, Brandie; Becker, Patricia (2 August 2018). "Exploring Definitions and Prevalence of Verbal Sexual Coercion and Its Relationship to Consent to Unwanted Sex: Implications for Affirmative Consent Standards on College Campuses". Behavioral Sciences. 8 (8): 69. doi:10.3390/bs8080069. ISSN 2076-328X. PMC 6115968. PMID 30072605.

- Bonnar-Kidd, Kelly K. (2010). "Sexual Offender Laws and Prevention of Sexual Violence or Recidivism". American Journal of Public Health. 100 (3): 412–9. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2008.153254. PMC 2820068. PMID 20075329.

- See Crimes Act 1900 (NSW) s 61 HA (3)

- s 61H(1) Crimes Act 1990

- Crimes Act 1958 (VIC)

- Criminal Law Consolidation Act 1935 (SA).

- Criminal Code Act 1913 (WA)

- Criminal Code Act 1983 (NT)

- Criminal Code Act 1899 (QLD)

- Criminal Code 1924 (TAS)

- Crimes Act 1900 (ACT)

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2005). Personal Safety Survey. Canberra: ABS

- Heath, M. (2005). The law and sexual offences against adults in Australia (Issues No. 4). Melbourne: Australian Centre for the Study of Sexual Assault

- Lievore, D. (2005). Prosecutorial decisions in adult sexual assault cases. Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice, 291, January. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology

- "Sexual assault laws in Australia". 27 February 2011. Archived from the original on 6 March 2017. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- Ryan v R [1967] HCA 2; 121 CLR 205

- He Kaw Teh v R (1985) 157 CLR 523

- R v Bilal Skaf [2005] NSWCCA 297,16 September 2005

- R v Mohommed Skaf [2005] NSWCCA 298, 16 September 2005

- Crimes Amendment (Aggravated Sexual Assault in Company) Act 2001 No 62

- Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act 1999 NSW

- Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Amendment (Victim Impact Statements) Act 2004 No 3

- "Criminal Code". Laws.justice.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- Mike Blanchfield (27 May 2011). "Woman can't consent to sex while unconscious, Supreme Court rules". The Toronto Star. Archived from the original on 12 June 2013. Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- Barry, Garrett; Boone, Marilyn (24 February 2017). "Protest follows not guilty verdict in RNC officer Doug Snelgrove sexual assault trial". CBC News. CBC News. Archived from the original on 4 March 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

Demonstration held on court steps following verdict

- Mullaley, Rosie (23 February 2017). "Case of police officer accused of sexual assault in jury's hands". The Telegram. Archived from the original on 23 February 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- "Here's why the issue of consent is not so clear in sexual assault cases". The Canadian Press. Global News. 3 March 2017. Archived from the original on 3 March 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- "'Consent is a very complex issue': Lawyer looks at Snelgrove sexual assault trial". CBC News. Canada: Yahoo!. 25 February 2017. Archived from the original on 4 March 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- "Kunarac, Vukovic and Kovac - Judgement - Part IV". Icty.org. Archived from the original on 12 March 2016. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- Bottke, Wilfried (1999). "Sexuality and Crime: The Victims of Sexual Offenses". Buffalo Criminal Law Review. 3 (1): 293–315. doi:10.1525/nclr.1999.3.1.293. JSTOR 10.1525/nclr.1999.3.1.293.

- "GERMAN CRIMINAL CODE". Gesetze-im-internet.de. Archived from the original on 15 November 2012. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- National SATU Guidelines Development Group. Rape/Sexual Assault: National Guidelines on Referral and Forensic Clinical Examination in Ireland. 3rd Edition; 2014. Available at www.hse.ie/satu

- "Welcome to the official South African government online site! | South African Government". Info.gov.za. 11 August 2016. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- "Sexual Offences Act 2003". Legislation.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 15 October 2016. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- "The Sexual Offences (Northern Ireland) Order 2008". Legislation.gov.uk. 26 May 2011. Archived from the original on 14 November 2011. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- "Sexual Offences (Scotland) Act 2009". Legislation.gov.uk. 26 May 2011. Archived from the original on 29 July 2011. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- "Sexual Assault". United States Department of Justice. 23 July 2014. Archived from the original on 10 October 2016. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- "State Law Report Generator". RAINN. Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network. Archived from the original on 14 September 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- Scheb, John M.; Scheb II, John M. (2008). Criminal Law (5 ed.). Cengage Learning. p. 20. ISBN 978-0495504801. Archived from the original on 6 November 2017.

- Larson, Aaron (13 September 2016). "Sexual Assault and Rape Charges". ExpertLaw. Archived from the original on 14 September 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- "PENAL CODE CHAPTER 22. ASSAULTIVE OFFENSES". Statutes.legis.state.tx.us. Archived from the original on 10 August 2011. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

Further reading

- Wishart, Guy (2003). "The sexual abuse of people with learning difficulties: Do we need a social model approach to vulnerability?". The Journal of Adult Protection. 5 (3): 14–27. doi:10.1108/14668203200300021.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |