South Sudanese Civil War

The South Sudanese Civil War (15 December 2013 – 22 February 2020) was a conflict in South Sudan between forces of the government and opposition forces. In December 2013, President Kiir accused his former deputy Riek Machar and ten others of attempting a coup d'état.[53][54] Machar denied trying to start a coup and fled to lead the SPLM – in opposition (SPLM-IO).[55] Fighting broke out between the Sudan People's Liberation Movement (SPLM) and SPLM-IO, igniting the civil war. Ugandan troops were deployed to fight alongside the South Sudanese government.[56] The United Nations has peacekeepers in the country as part of the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS).[57]

In January 2014 the first ceasefire agreement was reached. Fighting continued and would be followed by several more ceasefire agreements. Negotiations were mediated by "IGAD +" (which includes the eight regional nations called the Intergovernmental Authority on Development as well as the African Union, United Nations, China, the EU, USA, UK and Norway). A peace agreement known as the "Compromise Peace Agreement" was signed in August 2015.[57] Machar returned to Juba in 2016 and was appointed vice president.[58] Following a second breakout of fighting within Juba,[59] the SPLM-IO fled to the surrounding and previously peaceful Equatoria region. Kiir replaced Machar as First Vice President with Taban Deng Gai, splitting the opposition, and rebel in-fighting became a major part of the conflict.[60][61] Rivalry among Dinka factions led by the President and Paul Malong Awan also led to fighting.[62]

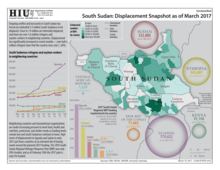

About 400,000 people were estimated to have been killed in the war by April 2018, including notable atrocities such as the 2014 Bentiu massacre.[50] Although both men had supporters from across South Sudan's ethnic divides, subsequent fighting had ethnic undertones. Kiir's Dinka ethnic group has been accused of attacking other ethnic groups and Machar's Nuer ethnic group has been accused of attacking the Dinka.[63] More than 4 million people have been displaced, with about 1.8 million of those internally displaced, and about 2.5 million having fled to neighboring countries, especially Uganda and Sudan.[64] Fighting in the agricultural heartland in the south of the country caused the number of people facing starvation to soar to 6 million,[65] causing famine in 2017 in some areas.[66] The country’s economy has also been devastated. According to the IMF in October 2017, real income had halved since 2013 and inflation was more than 300% per annum.[67]

In August 2018, another power sharing agreement came into effect.[68] On 22 February 2020, rivals Kiir and Machar struck a unity deal and formed a coalition government.[69]

Background

Previous rebellions

The region that became South Sudan in 2011 had traditionally functioned for millennia as a barter economy with the principle currency being cattle.[70] Cattle raids between different ethnic groups were an accepted and honorable way to acquire more cattle, and hence wealth.[70] However, there were widely accepted limits on the amount of violence permissible in cattle raids and tribal elders would intervene if cattle raid violence started to get out of control.[70] Furthermore, the antiquated weapons used in cattle raids were not likely to inflict mass casualties.[70] During the second war of independence from the Sudan, the government in Khartoum beginning in 1984 followed a consciously policy of "divide and rule" by arming young men with assault rifles and ammunition who were encouraged to engage in unlimited violence on cattle raids, hoping the resulting ethnic violence would cause so much disunity as to end the rebellion.[70] Through Khartoum's "divide and rule" policy failed to end the rebellion, but it did cause the breakdown of accepted norms regarding violence on cattle raids and an increase in ethnic tensions between the peoples of southern Sudan, leaving a legacy of distrust and bitterness that continues to this day.[70] The British journalist Peter Martell wrote that successive governments in Khartoum ruled southern Sudan with "staggering cruelty" right from the moment Britain granted independence to the Sudan in 1956, leading to generations of men who grew up only knowing power exercised in the most vicious manner possible and who had to come to copy their masters.[71]

The Comprehensive Peace Agreement signed in 9 January 2005 between the Sudan People's Liberation Movement (SPLM) and the government of the Sudan ended the war for independence that started in 1983. Under the terms of the peace agreement, a Southern Sudan Autonomous Region was created and run by the SPLM with a promise that a referendum would be held on independence in 2011. During the six years period of autonomy, the desire for independence kept in-fighting within the SPLM in check, but disputes arose over how to share the oil revenues.[72] One consequence of the war's end was the oil fields in southern Sudan could be developed far more extensively than was possible during the war and began to be pumped.[72] Between 2006-2009, sales of oil brought in an annual average of $2.1 billion U.S dollars to the Southern Sudan Autonomous Region.[72] Disputes between leading personalities in the SPLM over how to appropriate the oil revenues led to recurring tensions.[72] A system emerged during the autonomous period where SPLM leaders used the wealth generated by the oil to buy the loyalty of not only the troops, but the people at large, creating intense competition to control the oil.[71] After the 2011 referendum led to 98% of voters choosing independence from the Sudan, on 9 July 2011 South Sudan became an independent nation.[73]

In 2010, after a disputed election, George Athor led the South Sudan Democratic Movement in rebellion against the government. The same year, a faction of the South Sudan Democratic Movement, called the Cobra Faction, led by David Yau Yau rebelled against the government they accused of being prejudiced against the Murle. His faction signed a cease-fire with the government in 2011 and his militia was reintegrated into the army but he then defected again in 2012. After the army's notorious 2010 disarmament campaign with widespread abuses of the Shilluk people, who were alleging persecution by the ruling Dinka, John Uliny from the Shilluk people began a rebellion, leading the Upper Nile faction of the South Sudan Democratic Movement. Gabriel Tang, who led a militia allied to Khartoum during the Second Sudanese Civil War, clashed regularly with the SPLA until 2011 when his soldiers were reintegrated into the national army. In 2011, Peter Gadet led a rebellion with the South Sudan Liberation Army, but was reintegrated into the army the same year. In a strategy of co-option known as "big tent", the government often buys off community militia and pardons its leaders.[74] Others call the use of rebellion to receive public office as "bad culture"[75] and an incentive to rebel.[76]

President consolidates power

After rumors about a planned coup surfaced in Juba in late 2012, South Sudanese President Salva Kiir began reorganizing the senior leadership of his government, party, and military in an unprecedented scale.[77] In January 2013, Kiir replaced the inspector general of the national police service with a lieutenant from the army and dismissed six deputy chiefs of staff and 29 major generals in the army.[77] In February 2013, Kiir retired an additional 117 army generals[78] but this was viewed as troublesome in regards to a power grab by others.[79] Kiir had also suggested that his rivals were trying to revive the rifts that had provoked infighting in the 1990s.[80] In July 2013, Kiir dismissed Vice President Riek Machar, one-time leader of the Nasir revolt, along with his entire cabinet. Kiir suspended the SPLM Secretary-General Pagan Amum Okech and forbade him from leaving Juba or speaking to the media.[81] The decrees elicited fears of political unrest, with Machar claiming that Kiir's move was a step towards dictatorship and announcing that he would challenge Kiir in the 2015 presidential election.[82][83] He said that if the country is to be united, it cannot tolerate "one man's rule."[84] Kiir disbanded all of the top-level organs of the SPLM party, including the Political Bureau, the National Convention and the National Liberation Council in November 2013. He cited their failed performance and the expiration of their term limits.[85]

Ethnic tension

In 2010, Dennis Blair, then United States Director of National Intelligence, issued a warning that "over the next five years,...a new mass killing or genocide is most likely to occur in southern Sudan."[86][87] In 2011, there was fighting between the Murle and the Lou Nuer, mostly over raiding cattle and abducting children to raise as their own. The Nuer White Army released a statement stating its intention to "wipe out the entire Murle tribe on the face of the earth as the only solution to guarantee long-term security of Nuer's cattle".[88] Notably, in the Pibor massacre, an estimated 900[89] to 3000[90] people were killed in Pibor. Although Machar and Kiir are both members of the SPLM, they stem from different tribes with a history of conflict. Kiir is an ethnic Dinka, while Machar is an ethnic Nuer.[84][91]

Course of the conflict

Initial mutiny (2013)

It began on the evening of Sunday, 15 December 2013, at the meeting of the National Liberation Council in the Nyakuron neighbourhood of Juba, South Sudan's capital, when opposition leaders Dr. Riek Machar, Pagan Amum and Rebecca Nyandeng voted to boycott the meeting.[1]

The South Sudanese Sudan Tribune reported clashes breaking out in the Munuki neighbourhood[92] late on 14 December in Juba between members of the presidential guard.[84] Kiir also claimed that the fighting began when unidentified uniformed personnel started shooting at a meeting of the SPLM.[79] Former Minister of Higher Education Peter Adwok said that on the evening 15 December after the meeting of the National Liberation Council had failed, Kiir told Major General Marial Ciennoung to disarm his soldiers of the "Tiger Battalion," which he did. Adwok then controversially claims that the officer in charge of the weapons stores, opened them and rearmed only the Dinka soldiers. A Nuer soldier passing by questioned this and a fistfight then ensued between the two and attracted the attention of the "commander and his deputy to the scene." Unable to calm the situation, more soldiers got involved and raided the stores. It culminated in the Nuer soldiers taking control of the military headquarters. The next morning, he says that Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA) reinforcements arrived and dislodged the mutineers. He then explained standard procedure:

Military doctrine dictates that once a contingent of mutinous troops have been dislodged, appeal is made for their surrender and then disarmed. Those who remained loyal (to the president) are also disarmed to prevent bad blood. The loyal troops of Tiger, hailing mainly from Warrap and Aweil, have not been disarmed. In fact, they are the ones rampaging Juba, looting and shooting to kill any Nuer in the residential neighbourhoods."

Adwok was then placed on a list of wanted politicians, to which he said "this may be my last contribution, because, as I said, I'm waiting for the police in order to join my colleagues in detention."[93] On Christmas Day, five days after his controversial publication, Adwok was arrested and held for two days. He was later detained at the Juba airport when attempting to leave the country. His passport was also confiscated.[94]

The military headquarters near Juba University was then attacked with fighting continuing throughout the night.[82] The next day heavy gunfire and mortar fire were reported, and[84] UNMISS announced that hundreds of civilians sought refuge inside its facilities[82] Aguer said that some military installations had been attacked but that "the army is in full control of Juba," that the tense situation was unlikely to deteriorate, and an investigation was under way.[84] Several people were also injured during the fighting.[95] Juba International Airport was closed indefinitely;[96] Kenyan airlines Fly540 and Kenya Airways indefinitely suspended flights to Juba after the airport closed.[97] A dusk-to-dawn curfew was imposed[95] until further notice. State-owned SSTV went off-air for several hours. When it returned to broadcasting, it aired a message by President Salva Kiir.[95] The dissident group was said to include Sudan People's Liberation Movement (SPLM) founder John Garang's widow, Rebecca Garang.[96]

Foreign Minister Barnaba Marial Benjamin claimed that those that were a part of the coup were "disgruntled" soldiers and politicians led by Machar[82] and that at least ten people were confirmed to have been detained, seven were confirmed as former ministers including former Finance Minister Kosti Manibe and Pagan Amum was later reported to be held in house arrest.[98] Other arrests included those of Kiir's critics.[81] Information Minister Micheal Makuei Leuth claimed that Machar had left Juba with some soldiers and stolen cattle.[99]

President Salva Kiir spoke on national television on 16 December, having abandoned his signature suit and cowboy hat for military fatigues, and said, while surrounded by government officials, that the coup had been foiled and that it was orchestrated by a group of soldiers allied with the former vice president.[79][82][95] On 21 December, the government announced its unconditional readiness to hold peace talks with any rebel group, including Machar[100] In a Christmas message, Kiir warned of the fighting becoming a tribal conflict.[101] Chief Whip and MP from the large state of Eastern Equatoria, Tulio Odongi Ayahu, announced his support for Kiir.[102] The SPLM-affiliated youth group condemned the attempted overthrow of Kiir.[103]

Machar spoke for the first time since the crisis began on 18 December in which he said he was not aware of any coup attempt, but instead blamed Kiir for fabricating such allegations of a coup in order to settle political scores and target political opponents. He accused Kiir of inciting ethnic tensions to achieve his ends. He also said the violence was started by the presidential guard, which was founded by Kiir and told to report directly to him instead of the military.[80] He refused to deny or acknowledge support for Gadet but that "the rebels are acting in the right direction." On 22 December, Machar said he wanted to be the leader of the country and that "his" forces would maintain control of the country's oil fields.[104]

Former undersecretary of culture, Jok Madut Jok, warned that the violence could "escalate into tragic acts of ethnic cleansing".[105]

Beginning of rebellion (2013–2014)

.jpg)

Fighting also occurred near the presidential palace and other areas of Juba. Ajak Bullen, a doctor at a military hospital, said that "so far, we have lost seven soldiers who died while they were waiting for medical attention and a further 59 who were killed outside." The International Crisis Group (ICG) also reported that Machar's house had been bombarded and "surrounded, including with tanks", while "parts of Juba have been reduced to rubble".[81] The local Radio Tamazuj suggested UNMISS were absent from the streets in Juba and that December 2013's president of the UN Security Council had announced that the peacekeepers would not intervene in the fighting.[98] A semblance of calm returned to Juba by 18 December.[80] The UN reported that 13,000 people were taking refuge from the fighting in its two compounds in Juba.[81][99] Violence in Juba reportedly calmed, though there were unconfirmed reports of several students killed by security personnel at Juba University on 18 December. On 10 February 2014, the UN base in Juba was surrounded by armed government troops and policemen, who demanded that the UN surrender Nuer civilians sheltering there.[106]

The UN announced that thousands of people had sought refuge within the UN's compounds.[107] Two Indian peacekeepers were killed helping to protect 36 civilians in Akobo, Jonglei, when they were attacked by about 2,000 armed Nuer youths.[108] The attackers were apparently intending to kill the civilians sheltering at the UN base,[109] in a move condemned by the UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon.[110]

About 200 employees of petroleum operators, of which the three largest were China National Petroleum Corp, ONGC Videsh and Petronas, sought refuge at an UN compound in Bentiu.[111] This followed the deaths of 16 such workers, five workers at a field in Unity State on 18 December and another 11 at the Thar Jath field the next day. Government soldiers then took control of the fields and said that production continued normally.[112] The rebels had reportedly taken over at least some of the country's oil fields amidst fears of Sudan intervening in the country.[113]

In the north of Unity, Pariang county is home to the Rueng Dinka —the only Dinka group in the state. Fighting broke out in Pariang on 20 December, when some SPLA troops defected to the rebels. On 24 December, an estimated 400 defectors moved southwards from Jaw, the SPLA's northernmost operating base towards positions held by SPLA forces loyal to Koang Chuol. As of 26 December, the SPLA claimed they had destroyed 37 rebel vehicles in Pariang county, which remains in the hands of the SPLA.[114]

Following calls from the government of South Sudan, Uganda deployed its troops to Juba to assist in securing the airport and evacuating Ugandan citizens.[115] On 21 December a flight of three US Air Force V-22 Osprey aircraft en route to evacuate US nationals from Bor took small arms fire from the ground, injuring four Navy SEALs.[116] South Sudan blamed the rebels for the incident.[117] A second evacuation attempt by four UN and civilian helicopters succeeded in evacuating about 15 US nationals, Sudanese-Americans and those working in humanitarian operations, from the United Nations base in Bor on 22 December. Although the base was surrounded by 2,000 armed youths, a rebel commander had promised safe passage for the evacuation. In total 380 officials and private citizens as well as about 300 foreign citizens were flown to Nairobi.[118] The United States military announced a repositioning of its forces in Africa to prepare for possible further evacuations as the United Nations warned of the planned strikes.[119] Many of these reports have come from the hundreds of foreign oil company employees gathered at the airport to leave.[92] Five Ugandan and ten Kenyan citizens were also evacuated from Bor and then Juba before leaving the country. The Kenyan government said that there were 30,000 of its nationals in the country and that 10,000 had applied for emergency documents.[120]

On 22 December 2013, U.S. and Nigerian envoys were on their way to Juba to try to negotiate a solution.[104] The U.S. envoy to the country, Donald Booth, saying that having spoken to Kiir, the latter was committed to talks with Machar without preconditions.[121] Machar said that the rebel side was ready for talks that could possibly occur in Ethiopia. He said he wanted free and fair elections and that it is best if Kiir leaves.[122][123] His conditions for talks were that his "comrades", including Rebecca Garang and Pagan Amum, be released from detention to be evacuated to Addis Ababa. Information minister Makuei said those involved in the coup would not be released and dismissed claim that the rebels had taken the major oil fields.[32]

Fighting had spread to Bor by 17 December, where three people had died[124] and over 1,000 people sought refuge in the UN base.[80] The situation escalated when around 2,000 soldiers led by Peter Gadet revolted and attacked the city of Bor on 18 December. The rebels quickly seized much of the settlement.[125][126] Ethnically targeted violence was also reported and the Dinka feared a repeat of the Bor massacre.[105] On 23 December, Aguer said the army was on its way to Jonglei and Unity to retake territory.[119] On 24 December, the government of South Sudan claimed to have recaptured Bor.[127] Most of Gadet's troops had left by the end of the day.[128] On 27 December, Machar condemned Ugandan interference, claimed Ugandan air forces bombed their positions in Bor.[129] There was also tension at the UN compound in the city as armed fighters had entered it and about 17,000 civilians seeking protection were at the location.[130] The UN also reported that their base was being reinforced with additional protective barriers, including the area hosting the displaced civilians.[131] On 29 December, a U.N. helicopter spotted a group of armed youths 50 kilometres (31 mi) from Bor but could not confirm their numbers. On 30 December, South Sudanese government troops clashed with ethnic White Army militiamen and other rebel factions loyal to Machar late on Monday near Bor.[132] By 31 December, the rebels were reaching the center of Bor[133] and by 2 January, Nhial admitted government withdrawal from the city[134] and Kiir declared a state of emergency in Unity and Jonglei states, where rebels controlled the capitals.[135] On 4 January intense battles involving tanks and artillery were reported on the outskirts of Bor, which by this time had changed hands three times since fighting in as many weeks.[136] Rebels claimed that a South Sudanese army general has been killed in the fighting, as his convoy approaching Bor was ambushed. The SPLA brought large numbers of reinforcements bringing the total SPLA troops 25 km (16 mi) Bor close to 2,000.[137][138]

On 25 December, fighting continued in Malakal,[139] according to Ateny, who added that the oil fields were secured[140] and denied rebels had taken over the city. On 27 December, the army said it had taken back full control of Malakal, the administrative center of Upper Nile, a state which currently supplied all of South Sudan's crude oil, after fighting shut down oil fields in other areas.[141][43] By February 2014, the UN compound in Malakal housed around 20,000 people who had fled the conflict. Rebel forces claimed to have recaptured Malakal from the army, while army forces claimed to have held the city after heavy fighting. The UNMISS reported that on 14 January heavy fighting broke out near the UN compound in Malakal. One civilian was killed and dozens of civilians were wounded in that attack.[142][143] Civilians emptied out of the town, and at least 200 drowned when their overcrowded boat sank as they tried to flee across the Nile.[144][145] On 15 January, fighting continued in the streets of Malakal[146] with both sides claiming to control the town. On 18 February 2014, fighting between members of various ethnicities broke out within the UN Mission in the capital city of Upper Nile State, Malakal, resulting in ten deaths.[147]

.jpg)

In Bentiu, capital of Unity State, SPLA 4th Division divided along factional lines with troops, including division commander James Koang, clashed with loyal troops, who retreated from their barracks on 20 December 2013.[148] The next day, Koang announced allegiance to Machar and declared an ‘interim government’ of the state and state governor Nugen Monytuel fled Mayom county.[149][150] The loyal soldiers retreated to the outlying Abiemnom County and were reinforced by Western Bahr el Ghazal's 5th division and the Northern Bahr el Ghazal's 3rd division to take back Bentiu.[114] South Sudan Liberation Movement (SSLA) militia forces, led by the Bul Nuer commander Matthew Puljang, decided to support them.[114][5] By 27 December, a combined force of SSLA and SPLA seized Mayom, 90 kilometers from Bentiu, on 29 December. Peter Dak, the rebel commander in Mayom, announced that he fled the town on 7 January.[114][151] Around 8 January 2014, the SPLA forces advanced on Bentiu, which had been mostly evacuated,[114][152] securing the city on 10 January 2014.[114]

Peace talks and rebel split (2014–2015)

In January 2014, direct negotiations between both sides, as mediated by "IGAD +" (which includes the eight regional nations as well as the African Union, United Nations, China, the EU, USA, UK and Norway), began.[153][154] In order to ensure a stronger negotiating position, South Sudanese troops fighting alongside Ugandan troops retook every town held by the rebels, including Bor on 18 January[155] and Malakal on 20 January.[156] Government troops were assisted by Ugandan troops, against the wishes of IGAD[157] who feared a wider regional conflict.[158] Uganda announced they had joined the fight in January[159] after previously denying it,[160] saying the troops were to only to evacuate Ugandan nationals.[161] On 23 January 2014, representatives of the Government of South Sudan and representatives of rebel leader Riek Machar reached a ceasefire agreement in Ethiopia.[162][163] The deal also stipulated that 11 officials close to rebel leader Machar should be released.[162]

Only a few days later,[164] the rebels accused that a government takeover of Leer was a deliberate attempt to sabotage the second round of talks that were to start later in February.[165] The rebels threatened to boycott the second round talks, demanding the release of four remaining political prisoners and the withdrawal of Ugandan troops.[166] Later in February, the rebels attacked the strategic government controlled Malakal[167] and the government admitted withdrawal[168] and then, in March, the rebels admitted withdrawal, changing hands for the fifth time.[169] In April, rebels claimed once again to have seized Bentiu[170] and by 19 April South Sudan's army admitted to have "lost communication" with commanders battling in Unity state.[171] The 2014 Bentiu massacre occurred on 15 April in Bentiu when more than 200 civilians, all said to have been Dinkas,[172] were massacred by Nuer rebels. A mosque, hospital, and church were targeted where civilians had sought refuge from the fighting. After the fall of Bentiu, Salva Kiir sacked Army chief James Hoth Mai and replaced him with Paul Malong Awan.[31][173]

In May 2014, the government signed a peace agreement called the Greater Pibor Administrative Area peace agreement with the largely Murle group, the Cobra Faction of the South Sudan Democratic Movement, led by David Yau Yau. As part of the agreement, a semi-autonomous area called the Greater Pibor Administrative Area was created to increase the minority populations within its borders and David Yau Yau was appointed chief administrator, equivalent to state governor.[174] In February 2015, a largely Murle group, unhappy with the agreement with the government, split off from the Cobra Faction to form the Greater Pibor Forces and declared allegiance to Machar.[20] One of their disagreements with the government was the alleged provoking of the Murle to fight against anti-government Nuer groups in Jonglei.[175] In April 2016, Murle fighters in South Sudan crossed over to Gambela in Ethiopia and killed more than 200 people, stole 2000 cattle and kidnapped more than 100 children from the Nuer tribe.[176]

On 9 May 2014, President Salva Kiir and Riek Machar signed the second ceasefire in Addis Ababa, a one-page agreement recommitting to the first ceasefire.[177] Hostilities were to end in 24 hours while a permanent ceasefire would be worked on and it promised to open humanitarian corridors and allow "30 days of tranquility" so farmers can sow crops and prevent famine. Hours after the ceasefire was to be in effect, both sides accused each other of violating the ceasefire.[178] On 11 June 2014, both parties agreed to begin talks on the formation of a transitional government within 60 days and to a third ceasefire refraining from combat during this period.[179] However, the talks collapsed as both sides boycotted the talks,[180] and by 16 June, the ceasefire was reported to have been violated.[181] In August 2014, Kiir and leaders of South Sudan's neighbouring states sign a roadmap leading to a transitional government of national unity. Machar refuses to sign up, accusing leaders in the IGAD, a regional group involved in the negotiations, of tilting the process in favour of Kiir.[182] In November 2014, both parties renew the much-broken ceasefire and IGAD mediators give them 15 days to reach a power-sharing deal, threatening sanctions if they fail. This third ceasefire breaks down 24 hours later with fighting in the oil-rich north.[182] In January 2015, rival factions sign a reunification agreement in Arusha, Tanzania, but fighting continued.[182] In February 2015, Kiir and Machar signed a document on "Areas of Agreement" for a future transitional government of national unity and recommitted themselves to the ceasefire.[182] The talks later collapsed and fighting broke out in March.[183][184][185]

Arms dealers sold weapons to both sides.[186] A series of shadowy networks emerged to sell weapons with the principal sources of arms being Egypt, Uganda, Ukraine, Israel and China.[186] In July 2014, the Chinese arms manufacturer Norinco delivered a shipment of 95,000 assault rifles and 20 million rounds of ammunition to the government, providing enough bullets to kill every person in South Sudan twice over.[186] Not content with the arms shipment from Norinco, the government asked if it was possible for Norinco to set up a factory in South Sudan, a request that was declined.[186] An American arms dealer, Erik Prince, sold to the government for 43 million US dollars three Russian-made Mi-24 attack helicopters and two I39 jets.[186] The aircraft were flown by Hungarian mercenaries with one of the mercenaries, Tibor Czingali, posting photographs on his Facebook account of bullet holes in his jet.[186] In Spain, the police arrested a Franco-Polish arms dealer, Pierre Dadak, at his luxury villa in Ibiza.[186] Documents found at the villa showed that Dadak had a contract with the rebels to sell them 40,000 AK-47 assault rifles, 30,000 PKM machine guns and 200,000 boxes of ammunition.[186] The government's National Security Service in July 2014 signed a contract worth 264 million US dollars with a Seychelles-based shell company to buy 50,000 AK-47s, 20 million bullets and 30 tanks.[186] The demand for weapons had a disastrous impact on the elephant population as the rebels slaughtered elephants to sell their tusks on the black market to earn money to buy arms. In China and other east Asian nations, tusks are mistakenly believed to have medical qualities, leading to a flourishing and profitable black Ivory trade market. It was reported there was a "crisis" for elephants who were decimated.[187] The number of known elephants in South Sudan declined from 2, 300 in 2013 to 730 in 2016.[188] The arms-buying spree took place against the economic collapse of South Sudan. By end of 2014, South Sudan achieved the dubious honor of being ranked the number one failed state in the entire world.[189]

Johnson Olony led a militia that planned to be integrated into the SPLM government forces, but he switched to oppose the government when the government announced plans to carve up new states which the Shilluk felt was to divide their homeland.[190] On 16 May 2015, Olony's militia and elements of the SPLM-IO captured Upper Nile's capital, Malakal, as well as Anakdiar and areas around Kodok.[191] His Shilluk militia group now called itself the 'Agwelek forces'.[23] The group said they want to run their affairs independently from others in Upper Nile State, and SPLM-IO backed away from claims that it is in charge of Olony's group and stated that Olony's interests simply coincides with theirs.[192] SPLM-IO said they understood the feeling from the Shilluk community that they wanted a level of independence and that that was the reason the SPLM-IO last year created Fashoda state for the Shilluk kingdom and appointed Tijwog Aguet, a Shilluk, as governor.[23]

On 11 August 2015, Gabriel Tang,[60] Gathoth Gatkuoth, the former SPLM-IO logistics chief, and rebel commander Peter Gadet, announced that they and other powerful commanders had split from Riek Machar, and rejected ongoing peace talks, announcing that they would now combat Riek Machar's forces in addition to government forces.[49] Gathoth Gatkuoth states he wishes for a President who is neither Dinka nor Nuer and intended to register his group as a political group called the "Federal Democractic Party" and that their forces would be called the "South Sudan National Army".[27]

Compromise Peace Agreement and second Juba clashes (2015–2016)

In late August 2015, Salva Kiir signed a peace agreement previously signed by Riek Machar called the "Compromise Peace Agreement" mediated by IGAD +. The agreement would make Riek Machar the vice-president again.[182][193] The agreement established the Joint Monitoring and Evaluation Commission (JMEC) responsible for monitoring and overseeing implementation of the agreement. On 20 October 2015, Uganda announced that it will voluntarily withdraw its soldiers from South Sudan, in accordance to that peace agreement.[13] In January 2016, David Yau Yau dissolved the Cobra Faction of the South Sudan Democratic Movement and joined the SPLM.[194] In January Gathoth Gatkuoth joined with the government but was dismissed by his Federal Democratic Party for doing so.[195] In April 2016, as part of the peace deal, Machar returned to Juba with troops loyal to him and was sworn in as vice-president.[196]

On Christmas Eve 2015, Salva Kiir announced he was going forward with a plan to increase the number of states from 10 to 28 and then, five days later, swore in all new governors appointed by him and considered loyal to him.[190] The new borders give Kiir's Dinkas a majority in strategic locations.[190] Some observers feel that the government is holding on to the peace deal to maintain international aid while backing campaigns to increase Dinka control over land and resources traditionally held by other groups.[197] As the predominantly Shilluk Agwelek forces joined, in July 2016, with the SPLM-IO, which entered the peace agreement with the government, some Shilluk felt dissatisfied. After the establishment of the new states, a new group made up of mostly Shilluk formed the "Tiger Faction New Forces" (TFNF) in October 2015, led by General Yohanis Okiech.[198] They rejected joining the SPLM-IO or the peace agreement and called for the restoration of the original 1956 borders of the Shilluk territories.[199]

By this point, the Dinka militia leaders loyal to Kiir had grown rich by South Sudanese standards by confiscating cattle (still the main currency unit in rural areas) from the Nuer, giving them a vested interest in keeping the Nuer down.[200] In South Sudan, ownership of cattle is closely tied to a sense of masculinity and a man who does not own cattle is not only poor, but also felt to lack manliness.[200] Nuer men, deprived of their cattle, thirsted for revenge together with a burning desire to reclaim lost wealth, status and their sense of masculine pride, leading them to join rebel groups.[200] Furthermore, many of the Dinka leaders, now flushed with cattle, began to push into the province of Equatoria to seize the rich farmland for their cattle herds, causing the local farmers to fight back.[200] The British journalist Peter Martell wrote the war had started out as a conflict within the elite over control of the oil revenue, but had "evolved into anarchy, opportunism, and revenge" as the violence had acquired a momentum of its own with multiple clan leaders raising their own militias to battle over control of the cattle herds and land, struggles fought with little reference to either Kiir or Machar.[200]

Notably, the war ceased to be an ethnic struggle, instead becoming a clan conflict as both Dinka and Nuer clans were fought each another.[201] There were Dinka and Nuer clans professing loyalty to Kiir and Dinka and Nuer clans professing loyalty to Machar.[201] However, these protestations of loyalty should not be taken at face value. One clan leader who raised a militia, James Koach, who was nominally loyal to Machar told Martell in 2016: "I don't care what deal they sign in Juba. The deals are with the government and where is the government? They mean nothing to us and make no difference here. They took our wives and killed our children. My family's gone, so what do I care if I live or die? They took our cows. You who come from outside don't know what that means. Our cows are everything, because without them how do we survive? They are trying to wipe us out, to remove us from the earth".[202] By 2016, it was estimated that there were at least 20, 000 child soldiers fighting in South Sudan, and many experts on the subject such as the retired Canadian General Roméo Dallaire who campaigns against the use of child soldiers warned that having so many child soldiers would have a long-term deleterious impact on South Sudan.[203]

When Dinka cattle herders, allegedly backed by the SPLA, occupied farmland, Azande youth rose up into militias mostly with the Arrow Boys,[204] whose leader Alfred Karaba Futiyo Onyang declared allegiance to SPLM-IO[205] and claimed to have occupied parts of Western Equatoria.[206] A new rebel faction calling itself the South Sudan Federal Democratic Party (different from but related to the larger similarly named rebel faction led by Peter Gadet, Gabriel Chang and Gathoth Gatkuoth), made up mostly of Lotuko people formed during this time due to growing perceptions of mistreatment by the "Dinka" government and took over a SPLA outpost in Eastern Equatoria.[207] In February 2016, Dinka SPLA soldiers attacked a UN camp targeting Nuer and Shilluk who accused the government of annexing parts of their ancestral land.[208] About a year after the peace agreement was signed, groups of ethnic Dinka youth and the SPLA targeted members of the Fertit in Wau, killing dozens and forcing more than 120,000 to flee their homes.[209] As result, local Fertit tribal militias and groups allied with the SPLM-IO rose in rebellion, causing heavy clashes in the originally relatively peaceful Wau State, which continued for months.

_2.jpg)

Violence erupted in July 2016 after an attack outside of where President Kiir and Riek Machar were meeting in Juba. Fighting spread throughout the city. Over 300 people were killed and over 40 people were injured, including civilians.[210] In the following week, 26,000 fled to neighboring Uganda.[211] Indian Air Force evacuated Indian citizens from the country under Operation Sankat Mochan.[212] A spokesman for Riek Machar announced that South Sudan was "back to war" and that opposition forces based in areas of Juba had been attacked by forces loyal to the President.[213] Fighting involving heavy machine guns, mortars and tanks was reported in several parts of Juba on 10 July. Gun battles broke out near the airport and a UN base forcing the airport to close for safety reasons.[214] President Salva Kiir and first Vice-President Riek Machar ordered a ceasefire after days of intense violence.[215] Machar fled Juba after the clashes.

After a 48-hour ultimatum given by Kiir for Machar to return to Juba to progress with the peace agreement talks passed, the SPLA-IO in Juba appointed lead negotiator Taban Deng Gai to replace Machar and the government accepted him as acting vice-president. Machar said any talks would be illegal because Machar had previously fired Gai.[211] Machar, with assistance from the UN, went to exile, first to Kinshasa[216] then to Sudan and then to South Africa, where he was allegedly[217] kept in house arrest.[61]

After Machar's flight, Kiir sent his soldiers to rob the Central Bank of South Sudan at night, and put up $5 million US dollars stored in the central bank's vaults as a reward to anyone who could kill Machar.[201] Kiir's spokesman admitted to what had been done, claiming it was justified under the circumstances.[201]

Rebel infighting and splits among ruling Dinka (2016–2017)

.jpg)

In September 2016, Machar announced a call for armed struggle against Kiir[218] and in November, he said SPLM-IO would not participate in a workshop organized by JMEC, saying the peace agreement needs to be revised.[219] In September, Lam Akol, leader of the largest opposition party, Democratic Change, announced a new faction called the National Democratic Movement (NDM) to overthrow Kiir.[220] Yohanis Okiech, who led the largely Shilluk Tiger Faction New Forces, which split from Uliny's Agwelek forces, joined the predominantly Shilluk NDM[221] as deputy chief of general staff.[222] In the same month, the Cobra Faction of the South Sudan Democratic Movement, now led by Khalid Boutros declared war against the government.[75]

In December 2016, the United Nations reported that both sides were committing atrocities, stating that rape had reached "epic proportions" in South Sudan.[223] In a survey of women who fled to UN relief camps in Juba, 70% reported that they had been raped since December 2013.[223] Martell described the rampant sexual violence as not incidental to the war, but an integral and central part of the strategies of both sides, as "a tool for ethnic cleansing, as a means of humiliation and revenge".[223] Nor were foreign aid workers safe, with gunmen belonging to Kiir's Tiger Force stormed an UN relief camp at the Terrain Hotel on 11 July 2016, killed the journalist John Gatluak for being a Nuer, and proceeded to gang-rape 5 foreign aid workers as a "punishment" for foreign criticism of Kiir.[224] The UN "peacekeepers" from Nepal who were supposed to be guarding the Terrain Hotel camp did nothing, despite being only a 3 minute walk away from the hotel.[225] The UN's Special Envoy for Sexual Violence, Zainab Bangura, reported that nowhere in the entire world had she had ever seen a place with worse sexual violence than South Sudan.[223] The same study also reported that rape was not only common against women and children, but also against men as well, through the reluctance of men to admit that they had been raped made it difficult to place a precise number on the cases of male rape.[223] Yasmin Sooka, the chairwoman of the UN Commission for Human Rights in South Sudan, in her report wrote: "Perhaps the worse thing is that many now treat sexual violence as a "normal" facet of life for women. We are running out of adjectives to describe the horror".[226]

In response to the report, Samantha Power, the American ambassador to the UN, on 23 December 2016 asked the UN Security Council to place an arms embargo on South Sudan, asking: "So do we just sit on our hands until the government calls off the militias, to stop some of the most systematic sexual violence that we’ve seen in any conflict in our lifetimes?"[227] Power noted as South Sudan has no arms-manufacturing industry, both sides were entirely dependent on weapons from abroad to fight the war.[227] Power's proposal was defeated in the UN Security Council.[227] Of the members of the Security Council in 2016, the United States, France, the United Kingdom, New Zealand, the Ukraine, Spain, and Uruguay all voted for the arms embargo while Russia, China, Japan, Angola, Egypt, Malaysia, and Venezuela all abstained, causing the proposal for an arms embargo to be defeated.[228] Despite Power's proposal, the United States did not impose an arm embargo on American arms dealers selling weapons in South Sudan, and when one was finally imposed in 2017, it was and still is so full of loopholes as to be ineffective.[227] Outside of South Sudan, very people cared about the war.[226] One British security officer told Martell in 2016 that: "Killing for these people is a game. Life is so cheap here, it means nothing".[226] Martell wrote that everything he had seen in the war rebutted the "flippancy" of that remark, noting that mothers had often died fighting to protect their children from being raped.[226]

On the international front, the African Union, after the Juba clashes, backed plans for the deployment of troops from regional nations with a strong mandate similar to that of the United Nations Force Intervention Brigade that swiftly defeated the M23 rebels in the Democratic Republic of Congo as UN troops presently within the country have struggled to protect civilians.[229] In August 2016, the UN Security Council authorized such a force for Juba. The government initially opposed the move, claiming a violation of sovereignty.[230] With a resolution threatening an arms embargo if it blocked the new deployment, the government accepted the move with conditions such as the troops not being from neighboring countries, claiming they have interests at stake.[231] They also accepted a hybrid court to investigate war crimes.[232] The US pushed for an arms embargo and sanctions on Machar and army chief Paul Malong Awan through the Security Council, but it failed to receive enough votes to pass in December 2016.[233][234] After an independent report into UNMISS's failure to protect civilians in the Juba clashes, Secretary-General Ban sacked the commander of the UN force Lt Gen Johnson Mogoa Kimani Ondieki in November[235] and then the general's native Kenya declared that it would pull out of the key role it plays in the peace process[236] and withdrew its more than 1000 peacekeepers from UNMISS[237] before sending the troops back in with the start of the new UN secretary general's tenure.[238] On 30 April 2017, the first batch of the Regional Protection Force arrived under Brigadier General Jean Mupenzi of Rwanda[239] with the first phase of troops arriving in August.[240]

Among regional powers, Kiir met, in January 2017, with Egyptian president Abdel Fattah el-Sisi who also met with Kiir’s ally Ugandan President Museveni. Egypt had previously rejected the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam that Egypt feels would diminish its share of the Nile River and Ethiopian Prime Minister, Hailemariam Desalegn had accused Egyptian institutions of supporting terrorist groups in Ethiopia.[241] SPLM-IO alleged that a "dirty deal" was struck between Kiir and Egypt against Ethiopia while Kiir denied any diplomatic row.[242] SPLM-IO accused the Egyptian Air Force of bombing their positions on 4 February 2017 while Egypt denied it.[243] As a result of Sudan’s effective counterinsurgency strategy in the War in Darfur, the biggest rebel faction, the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM), retreated to South Sudan and became involved in mercenary and criminal activities according to a UN report.[244] SPLM-IO accused JEM as well as another rebel group in Sudan, SPLM-North of joining the conflict on the side of Juba.[243]

Since the July clashes, the fighting spread from the Greater Upper Nile to include the previously safe haven of Equatoria, where the bulk of SPLM-IO forces went for shelter from the clashes in Juba, located in Equatoria.[245] As Equatoria is the agricultural belt of the country, the number of people facing starvation soared to 6 million.[65] In November 2016, SPLM-IO claimed to have taken of the towns Bazi, Morobo and Kaljak.[219] While the rebels were mostly in retreat in the Upper Nile front, the rebels had gained ground on the Equatorian front where the SPLA was mostly restricted to its garrisons. This was attributed to local self-defence militias becoming increasingly integrated and the depopulation of towns resulting in the army having fewer supplies even while the rebels were already adapted to the bush.[246] However, after the fall of the main rebel headquarters of Pagak in the summer, the Southern headquarters in Lasu fell on 18 December 2017.[247] In late May, Kiir declared a unilateral ceasefire, which was taken with suspicion by others as it came after the late April government offensive that retook much territory and before the rainy season that would have anyway reduced fighting.[248] Three days after the government retook Lasu it signed another ceasefire with the rebels in December 2017.[249]

The other major front of the conflict remained the Greater Upper Nile, where government forces mostly fought John Uliny's SPLA-IO allied Agwelek forces. In a study of casualties up to April 2018, the deaths from violence peaked during this time between 2016-2017.[50] In October 2016, the rebels attempted to take Malakal[250] and by January 2017, fighting there had led to civilians deserting the country's second largest city.[251] In fighting in the Bahr el Ghazal region, pro-government militia Mathiang Anyoor attacked Wau killing up to 50 civilians in April 2017.[252] In the same month, SPLA-IO captured Raja, the capital of Lol State, while state governor Hassan claimed the city was immediately retaken.[253][254] A counteroffensive by the government starting in late April 2017 reversed most rebel gains,[255] captured the capital of the Shilluk kingdom, Kodok, from Uliny[256] and closed in on Pagak, which had been the SPLA-IO headquarters since 2014.[257][258] In July 2017, SPLA along with forces loyal to Taban Deng Gai took over the rebel-held town of Maiwut.[259][260][261] The government took over Pagak in August 2017 while the IO rebels still held territory in traditional Nuer areas of Panyijar Country in Unity state and rural areas of Jonglei and Akobo state.[262] SPLA-IO counterattacked Taban Deng Gai's SPLA-IO force, in an attempt to retake Pagak.[263]

An additional dimension of the conflict became the fighting between the opposition loyal to Machar and those supporting Taban Deng, largely within the Nuer majority former state of Unity.[61] Observers felt that Kiir had given up on negotiations by talking with Taban Deng instead of Machar during the peace talks, as Taban is seen by many in the opposition as a traitor.[61] As part of the "National Dialogue" initiated by Kiir in December 2016 where any former rebels who return to the capital will be given amnesty, about a dozen SPLM-IO officials defected to the government in January 2017.[264] Gabriel Tang, who was one of the generals to have defected from Machar during the peace talks in 2015, now allied with Lam Akol's largely Shilluk NDM and became its chief of staff.[265] In January 2017 Tang was killed in clashes with the SPLM-IO allied Agwelek forces led by John Uliny, a move the SPLM-IO proclaimed as a warning to rival rebel factions.[60] Two days later, Olony's forces ambushed and killed Yohanis Okiech, destroying the Tiger Faction New Forces.[266]

In February 2017, Deputy head of logistics Lt. Gen. Thomas Cirillo Swaka resigned, accusing Kiir of ethnic bias. This led to a series of high ranking resignations, including minister of Labour Lt. Gen. Gabriel Duop Lam[267] who also pledged allegiance to Machar. Swaka formed a new rebel group called the National Salvation Front (NAS) in March 2017.[268] In March 2017, Cirillo, a Bari from Equatoria, got additional support as SPLM-IO's Western Bahr al Ghazal commander, Faiz Ismail Futur, resigned to joined NAS while there are reports of six SPLM-IO shadow governors from Equatoria defecting to NAS.[269] In the same month, head of the Cobra Faction Khalid Boutros dissolved the Cobra Faction and merged it with Gen. Thomas Cirillo's NAS and claimed opposition groups are in consultation to unite their ranks.[270] In July 2017, John Kenyi Loburon, SPLA-IO's commander of Central Equatoria state switched to join NAS,[271] claiming favoritism towards Nuers in SPLA-IO and then as NAS general in the same month, fought with SPLA-IO in Central Equatoria in the first clashes between the two groups.[272] By November 2017, NAS captured areas in Kajo Keji from SPLM-IO, before both groups were routed by the government.[273][274] With broad support at its inception, by 2018, many had come to view NAS as simply "the Bari".[275]

Cracks were appearing along clan lines among the ruling Dinka. Kiir's Dinka of Warrap were in a feud with the Dinka of Paul Malong Awan's Aweil, who contributed the bulk of the government's fighting force in the war.[274] Around this time, the largely Dinka South Sudan Patriotic Army (SSPA) was formed in Northern Bahr el Ghazal, with the backing of powerful figures such as former presidential advisor Costello Garang Ring[276] and allegedly Malong Awan. In May 2017, Kiir reduced the power of the chief of staff position[277] and fired its powerful Dinka nationalist Malong Awan and replaced him with General James Ajongo Mawut, who is not a Dinka but a Luo.[278] Awan left Juba with most of his Mathiang Anyoor militia[279] while other militia members reportedly joined SSPA. By the end of 2017, SSPA had claimed to have captured territory around Aweil[62] and was seen as one of the biggest threats to Juba.[280] Awan was accused of plotting a rebellion and was detained but then released following pressure from the Dinka lobbying group, the Dinka Council of Elders.[281] In April 2018, Awan announced the launch of a rebel group named South Sudan United Front (SS-UF), which claimed to push for federalism.[282]

2018 peace agreement (2018–present)

By March 2018, nine opposition groups, including NAS, NDM of Lam Akol, FDP of Gabriel Chang, SSPA of Costello Ring and SSLM but notably not including SPLM-IO, had joined to form the South Sudan Opposition Alliance (SSOA) to collectively negotiate with the government.[283]

The United States put additional pressure on Juba by successfully passing an arms embargo on South Sudan in July 2018 through UN Security Council, following a 2016 failure, with Russia and China abstaining from voting this time.[284] Additionally, with neighboring Sudan facing economic troubles and relying on revenue from transporting oil from South Sudan, the Sudanese government, with a mix of incentives and coercion,[285] brought Kiir and SPLA-IO to hold talks in Khartoum. In June 2018, they signed another ceasefire where they agreed to form a transitional government for the 36 months leading to national elections and to African Union and IGAD peacekeepers to deploy to South Sudan and state boundaries would be drawn by commission chaired by a non-South Sudanese;[286][287] this ceasefire was violated just a few hours after coming into effect, when pro-government forces attacked rebels in Wau State.[288] SPLM-IO protested when the Parliament, where the President's party holds a majority of seats, extended the President's term and that of other officials by three years.[289] However, they eventually agreed to share power again with Machar to be one of five Vice Presidents and the 550 seat parliament to be divided with 332 going to Kiir's faction, 128 to Machar's group and the rest to other groups.[68] An SSOA faction led by NAS's Thomas Cirillo[290] rejected the deal citing their small share in the power sharing agreement.[291] As part of amnesty offered to groups following the peace deal, in August 2018, Brigadier General Chan Garang, claiming to lead a group of rebel soldiers from Malong's SS-UF, came back to the government along with 300 rebel soldiers in what was seen as a weakening of SS-UF.[292] In September 2018, South Sudan's President Salva Kiir signed a peace deal with main rebel leader Riek Machar formally ending a five-year civil war. The deal, mediated by Sudan and signed in the Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa, reinstated Machar in his former role as vice president.[293] Celebrations in Juba happened on 31 October 2018 with President of Sudan Omar Al-Bashir, Yoweri Museveni of Uganda, and Riek Machar among many other officials present.[294][295] However there were criticisms on the peace deal. It failed to address the issue of the concentration of power in the hands of the president (which triggered conflict in 2013).[296] It is argued that mistrust, rather than reconciliation, still defines the relationship between president Salva Kiir and Riek Machar and that the status quo will continue to produce violence and threat to long-lasting peace .[297] As part of the agreement, Machar was supposed to return to Juba in May to become Vice President again, citing security concerns, and asked for an extension of six months, which was accepted by Kiir.[298] Six months later, both sides agreed to delay the formation of a transitional unity government by 100 days.[299]

On the 5th anniversary of the war's outbreak in December 2018, the British journalist Peter Martell described South Sudan as a nation "in ruins" with 4.5 million people have been forced to leave their homes over the previous five years with over half having fled abroad to refugee camps in the Sudan or Uganda.[300] In an interview with Martell in April 2018, Kiir blamed the exodus of his own people on "social media" and denied the reports of atrocities, saying it was "a conspiracy against the government".[300] Kiir stated he would not step down as the part of any peace deal, saying "What is initiative in bringing peace if it is a peace that I will bring and then I step aside?"[301]

NAS became the main antagonist of the government, clashing with the government in the Central and Western part of Equatorial province starting in January 2019, leading to about 8,000 people fleeing Yei State.[302] NAS and FDP also alleged being attacked by SPLM-IO in Upper Nile State.[303] In August 2019, three rebel groups who were not signed up to the peace agreement - that of Cirillo's, whose rebel group was now known as South Sudan National Democratic Alliance (SSNDA), SS-UF of Paul Malong and the Real Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (R- SPLM) of Pagan Amum, resolved to unite their activities under “United South Sudanese Opposition Movements”.[304]

The most contentious issue delaying the formation of the unity government was whether South Sudan should keep 32 or return to 10 states. On 14 February 2020, Kiir announced South Sudan would return to 10 states in addition to three administrative areas of Abyei, Pibor, and Ruweng,[305][306] and on 22 February Riek Machar was sworn in as first vice president for the creation of the unity government, ending the civil war.[307]

On 30 April 2020, despite power-sharing agreement and arms embargo by the United Nations in place, the Amnesty International reported that South Sudan continues to import arms.[308]

Atrocities

Attacks on civilian centers

The government was accused by the US and aid groups among others of using starvation as a tactic of collective punishment for populations that support rebels by intentionally blocking aid.[309]

Ateny Wek Ateny, president's spokesman told to news conference, claimed that rebel troops went into the hospital in the town of Bor and slaughtered 126 out of 127 patients. Apparently an elderly man was blind and rebels spared him.[310] On 31 January 2014 in violation of the cease fire agreement, the signed Government troops attacked town of Leer in Unity State, forcing 240 Staff and patients of Doctors Without Borders in Leer to flee into the bush. Thousands of civilians fled to the bush. Doctors Without Borders lost contact with two thirds of its staff formerly located in Leer.[311][312] It is believed that the town was attacked by government troops as it is the home of former Vice President Riek Machar.[313] On 18 April, UN said that at least 58 people were killed and more than 100 others wounded in an attack against one of its bases in South Sudan sheltering thousands of civilians.[314] On 17 April 2014, 58 people were killed in an attack on the UN base in Bor.[315][316][317][318] 48 of those killed were civilians, while 10 were among the attackers.[317][317] UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon emphasised that any attack on UN peacekeepers constituted "a war crime",[315] while the UN Security Council expressed "outrage" at the attack.[319][320] In late 2016, in a government attack on Yei, three villages were destroyed with 3,000 homes burned in a single village.[321]

Ethnic cleansing

There were ethnic undertones to the conflict with the SPLM and SPLA, which has been accused of being dominated by the Dinka. A Dinka lobbying group known as the "Jieng Council of Elders" was often accused of being behind hardline SPLM policies.[322][323] While the army used to attract men from across tribes, during the war, the SPLA had largely constituted soldiers from the Dinka stronghold of Bahr el Ghazal,[324] and the army was often referred to within the country as "the Dinka army".[325] Much of the worst atrocities committed are blamed on a group known as "Dot Ke Beny" (Rescue the President) or "Mathiang Anyoor" (Brown caterpillar), while the SPLA claim that it is just another battalion.[326][325] Immediately after the alleged coup in 2013, Dinka troops, and particularly Mathiang Anyoor,[326][327] were accused of carrying out pogroms, assisted by guides, in house to house searches of Nuer suburbs,[328] while similar door to door searches of Nuers were reported in government held Malakal.[329] About 240 Nuer men were killed at a police station in Juba's Gudele neighborhood.[330][331] During the fighting in 2016-17 in the Upper Nile region between the SPLA and the SPLA-IO allied Upper Nile faction of Uliny, Shilluk in Wau Shilluk were forced from their homes and Yasmin Sooka, chairwoman of the Commission on Human Rights in South Sudan, claimed that the government was engaging in "social engineering" after it transported 2,000 mostly Dinka people to the abandoned areas.[332] The king of the Shilluk Kingdom, Kwongo Dak Padiet, claimed his people were at risk of physical and cultural extinction.[333] In the Equatoria region, Dinka soldiers were accused of targeting civilians on ethnic lines against the dozens of ethnic groups among the Equatorians, with much of the atrocities being blamed on Mathiang Anyoor.[325] Adama Dieng, the U.N.'s Special Adviser on the Prevention of Genocide, warned of genocide after visiting areas of fighting in Yei.[334] Khalid Boutros of the Cobra faction as well as officials of the Murle led Boma State accuse the SPLA of aiding attacks by Dinka from Jonglei state against Boma state,[335][336] and soldiers from Jonglei captured Kotchar in Boma in 2017.[337]

The SPLM-IO is predominantly Nuer and its head, Machar, had previously committed the Bor massacre of mostly Dinka civilians in 1991. In 2014, the Bentiu massacre occurred when Bentiu was recaptured by rebels April 2014 and 200 people were killed in a mosque. Rebels separated the people and picked out those from opposing ethnic groups who they then executed.[338]

Child soldiers

Since the conflict began, more than 17,000 children were used in the conflict, with 1,300 recruited in 2016.[339]

Sexual violence

Reported incidents of sexual violence rose 60% in 2016, with Mundri in Equatoria's Amadi State being called the epicenter of the problem.[340] A UN survey found that 70% of women who were sheltering in camps had been raped since the beginning of the conflict, with the vast majority of rapists being police and soldiers,[341] and that 80% had witnessed someone else getting sexually assaulted.[342] The SPLA were reported to have recruited militias and young men in Unity state to take back rebel-held areas. They were given guns and their pay was what they could loot and women they could capture, who were raped.[343]

Violence against UN and foreign workers

It has been argued that with increased tension with the UN and outside powers over the government's actions there was a new shift in violence by the government against foreign peacekeepers, aid workers and diplomats.[344] NGOs are viewed with suspicion, with the Minister of Cabinet Affairs claiming "most of the [humanitarian] agencies are here to spy on the government."[345] During the 2016 Juba clashes, 80-100 South Sudanese troops entered the Terrain hotel facility and gang raped five international aid workers, singling out Americans for abuse, with nearby peacekeepers refusing to help the victims.[346][344] In July, soldiers ransacked a World Food Programme warehouse, stealing enough food to feed 220,000 people for a month, worth about $30 million.[344] In July, a Rocket-propelled grenade was fired near a UN peacekeepers' vehicle with two Chinese peacekeepers dying after the government refused passage to a clinic 10 miles away.[344] In December 2016, two staff members of the Norwegian Refugee Council were expelled from the country without a formal explanation.[347] In the deadliest attack on aid workers, six aid workers were killed in an ambush on 25 March 2017 bringing the number of aid workers killed since the start of the war to at least 79.[348]

Violence came from the rebel side as well. On 26 August 2014, a UN Mi-8 cargo helicopter was shot down, killing 3 Russian crew members, and wounding another. This occurred 9 days after rebel commander Peter Gadet threatened to shoot down UN aircraft, which he alleged were transporting government forces.[349]

Casualties

Mortality

During the first two days of fighting after 15 December, reports indicated that 66 soldiers had been killed in clashes in Juba,[350][351][352] and at least 800 injured.[353] By 23 December, the number of dead had likely surpassed 1,000 people[104][354] while an aid worker in the country estimated that the death toll was most likely in the tens of thousands.[33] The International Crisis Group reported on 9 January 2014 that up to 10,000 people were estimated to have died. In November 2014, the International Crisis Group estimated the death toll could be between 50,000 and 100,000.[355] A senior SPLA officer stated in November 2014 that the number of government soldiers killed and wounded topped 20,000, with 10,659 soldiers killed from January to October 2014 and 9,921 seriously wounded, according to a report by Radio Tamazuj.[356] By March 2016, after more than two years of fighting, some aid workers and officials who did not want to speak on the record said the true figure might be as high as 300,000.[357] A study by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine of deaths leading up to April 2018, reported that about 383,000 people are conservatively[64] estimated to have died as a result of the war, while the actual may be considerably higher, with 190,000 deaths directly attributed to violence and most of the deaths in Jonglei, Unity and Equatoria.[50]

Two Indian UN peacekeepers were killed on 18 December when their base was stormed by rebels, and three US military Osprey aircraft were fired upon leading to four American service personnel being wounded.[358] On 21 January 2014 Ankunda said that 9 Ugandan soldiers died in a rebel ambush at Gemeza a week before, and 12 others had been killed in total since 23 December.[48]

Displaced people

More than 4 million people have been displaced, with about 1.8 million internally displaced and about 2.5 million having fled to neighboring countries, especially Kenya, Sudan, and Uganda.[64] This makes it the world's third-largest refugee population after Syria and Afghanistan. About 86% of the refugees are women and children.[359] Uganda, which took more refugees in 2016 than all of those who crossed the Mediterranean into Europe,[360] has had a notably generous policy. Refugees are allowed to work and travel and families get a 30-metre by 30-metre plot of land to build a home with additional space for farming. In just six months since being built, the Bidi Bidi Refugee Settlement in Uganda became the single largest refugee settlement on earth.[361] However, the Ugandan government is seen as an ally of Kiir's crackdown on rebels, although with an increasing refugee population, Uganda has pressured Kiir to make peace.[362] The largest contingent of the Refugee Olympic Team at the 2016 Summer Olympics came from South Sudan, including its flag bearer.

Starvation

After the second Juba clashes, fighting intensified in the Equatoria region. As this is the agricultural heart of the country, the number of people facing starvation in the already food insecure nation soared to 6 million.[65] In February 2017, famine was declared in Unity state by the government and the United Nations, the first declaration of famine anywhere in the world in six years.[66] Days after the declaration of famine, the government raised the price of a business visa from $100 to $10,000, mostly aimed at aid workers, citing a need to increase government revenue.[345]

See also

- Central African Republic conflict (2012–2014)

- International reaction to the South Sudanese Civil War

Notes

- The SPLM-IO accused JEM of supporting Kiir's government since 2013, though JEM has denied any involvement and claims to maintain neutrality in the South Sudanese Civil War.[6] The Sudanese government,[7] aid workers[6] and other sources[8] have however affirmed that JEM is taking part in conflict on the side of the South Sudanese government.[9]

- The Cobra Faction openly opposed the government until 2014, and remained in relative opposition until 2015, when it divided into a pro-government and pro-SPLM-IO faction, the latter of which formed the Greater Pibor Forces. In early 2016, the Cobra Faction effectively disbanded, when the remaining group joined the government.[19][20][21] In September 2016, however, the Cobra Faction was declared restored by some of its commanders and declared that it had resumed its struggle against the government.[22]

- Zangil served as commander of the SSDM/A - Cobra Faction since 2013 until he deserted with much of his troops to the SPLM-IO in 2015, forming the "Greater Pibor Forces".[19][20]

- Yau Yau led the SSDM/A - Cobra Faction in open opposition to the SPLM government until 2014, and in relatively peaceful autonomy until 2015, when much of his forces deserted to the SPLM-IO. In 2016, he and his remaining loyalists joined the SPLM.[19][21][34]

References

- "It wasn't a coup: Salva Kiir shot himself in the foot", South Sudan nation

- Burke, Jason (12 July 2016). "South Sudan: is the renewed violence the restart of civil war?". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- "South Sudan on verge of civil war, death toll rises".

- James Copnall (21 August 2014). "Ethnic militias and the shrinking state: South Sudan's dangerous path". African Arguments. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- "Kiir's Dinka Forces Join SSLA Rebels". Chimpreports. Archived from the original on 16 January 2014. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- Small Arms Survey (2014), p. 7.

- Small Arms Survey (2014), pp. 14, 17.

- "South Sudan deploys more troops to Upper Nile as fighting intensifies". South Sudan News Agency. 9 February 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- Small Arms Survey (2014), pp. 7, 11, 14.

- Small Arms Survey (2014), pp. 10, 11, 20.

- Craze, Tubiana & Gramizzi (2016), p. 160.

- "Ethiopian opposition leader denies supporting South Sudan against rebels". Sudan Tribune. 6 April 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- Clottey, Peter (22 October 2015). "Uganda Begins Troop Withdrawal from South Sudan". VOA News. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- "Egypt supports South Sudan to secure Nile share". Al Monitor. 24 February 2015.

- "United Nations Mission in the Republic of South Sudan". UNMISS Facts and Figures. UN. Retrieved 23 January 2012.

- "Mandate". United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS). 16 October 2015.

- "South Sudan oil town changes hands for fourth time. Why?". The Christian Science Monitor. 5 May 2014. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- "South Sudan: 'White Army' militia marches to fight". USA Today. 28 December 2013.

- "David Yau Yau surrenders Cobra-faction to a General linked to the SPLA-IO: Cobra-faction's splinter group". South Sudan News Agency. 12 January 2016.

- "Murle faction announces defection to S. Sudan rebels". Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- "South Sudan's Boma state violence displaces hundreds". Sudan Tribune. 31 March 2016.

- "Top Cobra Faction general defects from Kiir government". Radio Tamazuj. 27 September 2016.

- "Johnson Olony's forces prefer independent command in Upper Nile state". sudantribune.com. 17 May 2015. Retrieved 23 June 2015.

- "Government Questions SPLM/A-IO About The Position Of Gen. Johnson Olony". gurtong. 2 April 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- "The Conflict in Upper Nile". www.smallarmssurveysudan.org. 8 May 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- "S. Sudan's Otuho rebels unveil objectives for armed struggle". Sudan Tribune. 4 December 2015. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- "South Sudan General Gathoth Gatkuoth explains to Karin Zeitvogel why he broke with Riek Machar". voanews.com. 12 August 2015. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- "Changson dismisses Gathoth Gatkuoth as FDP group splits over advance team to Juba". sudantribune.com. 12 July 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- "S. Sudan army in control of Wau town after heavy gunfire". sudantribune.com. 12 July 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2016.

- "S. Sudan rebels accuse government of backing Ethiopian rebels". Sudan Tribune. 18 March 2015. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- "South Sudan's president sacks army chief". The Daily Star. Lebanon. 23 April 2014. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- "South Sudan rebel leader sets out conditions for talks". Trust. Thomson Reuters Foundation. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- Daniel Howden in Juba. "South Sudan: the state that fell apart in a week". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- "Pibor's Yau Yau joins SPLM". Sudan Tribune.

- "Another S Sudanese rebel commander killed near Sudan border". Radio Tamazuj. 7 January 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- IISS 2015.

- "Major role for Ugandan army in South Sudan 'until the country is stable'". Radio Tamazuj. 31 January 2014. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- "South Sudan". The United Nations. CA. 23 June 2015. Archived from the original on 25 April 2015. Retrieved 23 June 2015.

- "Pride and reverence reign as UNMISS celebrates International Day of UN Peacekeepers in South Sudan". UN. 29 May 2019. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- "South Sudan's army advances on rebels in Bentiu and Bor". BBC. 9 January 2014. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- "South Sudan rebels claim 700 government troops defect". The Daily Star. 6 February 2014.

- "South Sudan army advances on rebel towns before peace talks". Reuters. 2 January 2014.

- "South Sudan forces battle White Army". The Daily Star. LB. 29 December 2013.

- "25,000 rebels march on strategic South Sudan town". IR: Press TV. 29 December 2013. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014.

- "Thousands of Machar-led fighters "defect" to new rebel group". Sudan Tribune. 29 July 2017. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- "South Sudan army denies rebel capture of military base in Aweil". Sudan Tribune. 17 June 2017. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- "South Sudan's military casualties top 20,000". Archived from the original on 4 February 2016.

- "South Sudan President Salva Kiir hits out at UN". BBC. 21 January 2014.

- "South Sudan rebels split, reject peace efforts". News. Yahoo. 11 August 2015.

- "Study estimates 190,000 people killed in South Sudan's civil war". Reuters. 26 September 2018. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- "Daily Press Briefing by the Office of the Spokesperson for the Secretary-General". United Nations. 10 February 2017.

- "4 Kenyans dead as South Sudan evacuation ends". KE: Capital FM. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- Koos, Carlo; Gutschke, Thea (2014). "South Sudan's Newest War: When Two Old Men Divide a Nation". GIGA Focus International Edition (2). Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- Kulish, Nicholas (9 January 2014). "New Estimate Sharply Raises Death Toll in South Sudan". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- "South Sudan opposition head Riek Machar denies coup bid". bbcnews.com. 18 December 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- "Yoweri Museveni: Uganda troops fighting South Sudan rebels". BBC News. 16 January 2014.

- "South Sudan country profile". BBC.

- "South Sudan rebel chief Riek Machar sworn in as vice-president". bbcnews.com. 26 April 2016. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- "South Sudan's Riek Machar in Khartoum for medical care". aljazeera. 23 August 2016. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- "Top rebel commander killed in clashes in Upper Nile". Radio Tamazuj. Archived from the original on 9 January 2017. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- "The revenge of Salva Kiir". foreignpolicy. 2 January 2017.

- "Rebel group claims capture of two areas in Northern Bahr al Ghazal". Radio Tamazuj. 15 June 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2018.

- "South Sudan 'coup leaders' face treason trial". BBC News. 29 January 2014.

- "A new report estimates that more than 380,000 people have died in South Sudan's civil war". Washington Post. 26 September 2018. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- "Starvation threat numbers soar in South Sudan". aljazzera. 25 November 2016.

- "South Sudan declares famine in Unity State". BBC News. 20 February 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- "As South Sudan implodes, America reconsiders its support for the regime". The Economist. 12 October 2017.

- "South Sudan's warring leaders agree to share power, again". Washington Post. 25 July 2018. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- "South Sudan rivals strike power-sharing deal". BBC News. 22 February 2020. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- Martell 2019, p. 125.

- Martell 2019, p. xx.

- Martell 2019, p. 176.

- Martell 2019, p. 206.

- "South Sudan's never ending war". Irinnews. 12 October 2016.

- "Militant Faction Vows Again to Fight S. Sudan Government". Voice of America. 27 September 2016.

- "Who's to blame in South Sudan?". Boston Review. 28 June 2016.

- "Kiir appoints new head of South Sudan police". Sudan Tribune. 22 January 2013. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- "South Sudan president retires over 100 army generals". Arab News. Agence France-Presse. 18 February 2013. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- Musaazi Namiti (17 December 2013). "Analysis: Struggle for power in South Sudan". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- "South Sudan violence spreads from capital". Al Jazeera. 4 October 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- Hannah McNeish (17 December 2013). "South Sudan teeters on the brink". Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- "S Sudan president says coup attempt 'foiled'". Al Jazeera. 16 December 2013. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- "South Sudan gripped by power struggle". Al Jazeera. 28 July 2013. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- "Heavy gunfire rocks South Sudan capital". Al Jazeera. 16 December 2013. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- "S. Sudan's SPLM confirms dissolution of all structures". Sudan Tribune. 23 November 2013. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- Abramowitz, Michael; Lawrence Woocher (26 February 2010). "How Genocide Became a National Security Threat". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- "Sudan: Transcending tribe". Al Jazeera English. Archived from the original on 17 March 2011. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- Ferrie, Jared (27 December 2011). "United Nations Urges South Sudan to Help Avert Possible Attack". Bloomberg. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- "Incidents of intercommunal violence in Jonglei state" (PDF). UNMISS. Retrieved 23 November 2016.