Sodomy law

A sodomy law is a law that defines certain sexual acts as crimes. The precise sexual acts meant by the term sodomy are rarely spelled out in the law, but are typically understood by courts to include any sexual act deemed to be unnatural or immoral.[1] Sodomy typically includes anal sex, oral sex, and bestiality.[2][3][4] In practice, sodomy laws have rarely been enforced against heterosexual couples, and have mostly been used to target homosexuals.[5]

| Sex and the law |

|---|

|

| Social issues |

|

|

Specific offences (Varies by jurisdiction) |

|

| Sex offender registration |

| Portals |

|

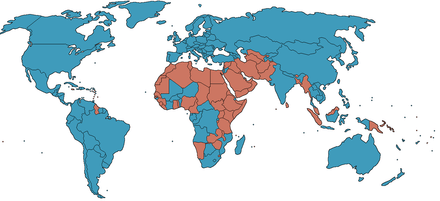

As of July 2020, 68 countries as well as five sub-national jurisdictions[lower-alpha 1] have laws criminalizing homosexuality.[6] In 2006 that number was 92.[7][8] Among these 68 countries, 43 criminalize not only male homosexuality but also female homosexuality. In 11 of them, homosexuality is punished with the death penalty.[6]

In 2011, the United Nations Human Rights Council passed an LGBT rights resolution, which was followed up by a report published by the UN Human Rights Commissioner which included scrutiny of the mentioned codes.

History

Criminalization

The Middle Assyrian Law Codes (1075 BC) state: If a man has intercourse with his brother-in-arms, they shall turn him into a eunuch. This is the earliest known law condemning the act of male-to-male intercourse in the military.[9]

In the Roman Republic, the Lex Scantinia imposed penalties on those who committed a sex crime (stuprum) against a freeborn male minor. The law may also have been used to prosecute male citizens who willingly played the passive role in same-sex acts.[10] The law was mentioned in literary sources but enforced infrequently; Domitian revived it during his program of judicial and moral reform.[11] It is unclear whether the penalty was death or a fine. For adult male citizens to experience and act on homoerotic desire was considered permissible, as long as their partner was a male of lower social standing.[12] Pederasty in ancient Rome was acceptable only when the younger partner was a prostitute or slave.

Most sodomy related laws in Western civilization originated from the growth of Christianity during Late Antiquity.[13] Note that today some Christian denominations allow gay marriage and the ordination of gay clergy.[14]

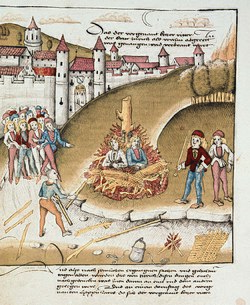

Starting in the 1200s, the Roman Catholic Church launched a massive campaign against sodomites, especially homosexuals.[15] Between the years 1250 and 1300, homosexual activity was radically criminalized in most of Europe, even punishable by death.[15]

In England, Henry VIII introduced the first legislation under English criminal law against sodomy with the Buggery Act of 1533, making buggery punishable by hanging, a penalty not lifted until 1861.

Following Sir William Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England,[16] the crime of sodomy has often been defined only as the "abominable and detestable crime against nature", or some variation of the phrase. This language led to widely varying rulings about what specific acts were encompassed by its prohibition.

Decriminalization

In 1786 Pietro Leopoldo of Tuscany, abolishing death penalty for all crimes, became not only the first Western ruler to do so, but also the first ruler to abolish death penalty for sodomy (which was replaced by prison and hard labour).

In France, it was the French Revolutionary penal code (issued in 1791) which for the first time struck down "sodomy" as a crime, decriminalizing it together with all "victimless-crimes" (sodomy, heresy, witchcraft, blasphemy), according with the concept that if there was no victim, there was no crime. The same principle was held true in the Napoleon Penal Code in 1810, which was imposed on the large part of Europe then ruled by the French Empire and its cognate kings, thus decriminalizing sodomy in most of Continental Europe.

In 1830, Emperor Pedro I of Brazil signed a law into the Imperial Penal Code. It eliminates all references to sodomy.[17]

During the Ottoman Empire, homosexuality was decriminalized in 1858 as part of wider reforms during the Tanzimat period.[18][19]

The death penalty was not lifted in England and Wales until 1861.

In 1917, following the Bolshevik Revolution led by V.I. Lenin and Leon Trotsky, Russia legalized homosexuality.[20] However, when Joseph Stalin came to power in 1920s, these laws were reversed until homosexuality was effectively made illegal again by the government.[21][22]

During the First Czechoslovak Republic (1918–1938), there was a movement to repeal sodomy laws. It has been claimed that this was the first campaign to repeal anti-gay laws that was spearheaded primarily by heterosexuals.[23]

After the publishing of the 1957 Wolfenden report in the UK, which asserted that "homosexual behaviour between consenting adults in private should no longer be a criminal offence", many western governments, including many U.S. states, repealed laws specifically against homosexual acts. However, by 2003, 13 U.S. states still criminalized homosexuality, along with many Missouri counties, and the territory of Puerto Rico, but in June 2003, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Lawrence v. Texas that state laws criminalizing private, non-commercial sexual activity between consenting adults at home on the grounds of morality are unconstitutional since there is insufficient justification for intruding into people's liberty and privacy.

There have never been Western-style sodomy related laws in the People's Republic of China, Taiwan, North Korea, South Korea, Poland, or Vietnam. Additionally, Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia were part of the French colony of Indochina; male homosexual acts have been legal throughout the French Empire since the issuing of the aforementioned French Revolutionary penal code in 1791.

Criminalization in modern days

This trend among Western nations has not been followed in all other regions of the world (Africa, some parts of Asia, Oceania and even western countries in the Caribbean Islands), where sodomy often remains a serious crime. For example, male homosexual acts, at least in theory, can result in life imprisonment in Barbados and Guyana.

As of 2019, sodomy related laws have been repealed or judicially struck down in all of Europe, North America, and South America, except for Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines.

In Africa, male homosexual acts remain punishable by death in Mauritania, Sudan, and some parts of Nigeria and Somalia. Male and sometimes female homosexual acts are minor to major criminal offences in many other African countries; for example, life imprisonment is a prospective penalty in Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia.[24] A notable exception is South Africa, where same-sex marriage is legal.

In Asia, male homosexual acts remain punishable by death in Afghanistan, Iran, Qatar, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Yemen.[24] But anti-sodomy laws have been repealed in Israel (which recognises but does not perform same-sex marriages), Japan, Kazakhstan, the Philippines, and Thailand.

| Being LGBTI should be a crime[25] | % Agree | % Disagree |

|---|---|---|

| Nigeria | 59 | 23 |

| Ghana | 54 | 25 |

| Pakistan | 54 | 28 |

| Uganda | 53 | 31 |

| Saudi Arabia | 49 | 32 |

| Jordan | 47 | 31 |

| Kenya | 46 | 37 |

| UAE | 45 | 32 |

| Egypt | 44 | 35 |

| Zimbabwe | 44 | 33 |

| Algeria | 43 | 35 |

| Iraq | 43 | 35 |

| Kazakhstan | 41 | 45 |

| Morocco | 39 | 39 |

| Indonesia | 38 | 37 |

| Malaysia | 35 | 40 |

| Turkey | 31 | 48 |

| India | 31 | 50 |

| Russia | 28 | 55 |

| Israel | 24 | 59 |

| Poland | 23 | 53 |

| Ukraine | 22 | 56 |

| South Africa | 22 | 61 |

| UK | 22 | 61 |

| Jamaica | 20 | 47 |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 20 | 52 |

| Philippines | 20 | 59 |

| China | 20 | 59 |

| Serbia | 19 | 58 |

| Bolivia | 18 | 54 |

| Dominican Republic | 18 | 56 |

| France | 17 | 58 |

| Vietnam | 17 | 61 |

| Peru | 16 | 57 |

| Australia | 15 | 66 |

| Netherlands | 15 | 76 |

| Nicaragua | 14 | 56 |

| Ecuador | 14 | 59 |

| Colombia | 13 | 60 |

| Venezuela | 13 | 60 |

| Chile | 13 | 65 |

| United States | 13 | 65 |

| Argentina | 13 | 67 |

| Canada | 13 | 69 |

| Spain | 13 | 72 |

| Japan | 12 | 61 |

| Mexico | 12 | 62 |

| Costa Rica | 12 | 64 |

| New Zealand | 12 | 64 |

| Ireland | 12 | 73 |

| Brazil | 11 | 68 |

| Italy | 11 | 74 |

| Croatia | 9 | 72 |

| Portugal | 9 | 75 |

Sodomy-related legal positions by country

Australia

Upon colonisation in 1788, Australia inherited laws from the United Kingdom including the Buggery Act of 1533. These were retained in the criminal codes passed by the various colonial parliaments during the 19th century, and by the state parliaments after Federation.[26]

Following the Wolfenden report, the Dunstan Labor government introduced a consenting adults in private type legal defence in South Australia in 1972. This defence was initiated as a bill by Murray Hill, father of former Defence Minister Robert Hill, and repealed the state's sodomy law in 1975. The Campaign Against Moral Persecution during the 1970s raised the profile and acceptance of Australia's gay and lesbian communities, and other states and territories repealed their laws between 1976 and 1990. The exception was Tasmania, which retained its laws until the Federal Government and the United Nations Human Rights Committee forced their repeal in 1997.

Male homosexuality was decriminalised in the Australian Capital Territory in 1976, then Norfolk Island in 1993, following South Australia in 1975 and Victoria in 1981. At the time of legalization (for the above), the age of consent, rape, defences, etc. were all set gender-neutral and equal . Western Australia legalised male homosexuality in 1989 – Under the Law Reform (Decriminalization of Sodomy) Act 1989, as did New South Wales and the Northern Territory in 1984 with unequal ages of consent of 18 for New South Wales and the Northern Territory and 21 for Western Australia. Then since 1997, the states and territories that retained different ages of consent or other vestiges of sodomy laws have tended to repeal them later; Western Australia did so in 2002, and New South Wales and the Northern Territory did so in 2003. Tasmania was the last state to decriminalise sodomy, doing so in 1997 after the groundbreaking cases of Toonen v Australia and Croome v Tasmania (it is also notable that Tasmania was the first jurisdiction to recognize same-sex couples in Australia since 2004 under the Relationships Act 2003.[27]) In 2016, Queensland became the final Australian jurisdiction to equalise its age of consent for all forms of sexual activity at 16 years, after reducing the age of consent for anal sex from 18 years.[28]

Brazil

Brazilian criminal law does not punish any sexual act performed by consenting adults, but allows for prosecution, under statutory rape laws, when one of the participants is under 14 years of age and the other an adult, as per Articles 217-A of the Brazilian Penal Code. Pedophilic acts are also criminalized by the Children and Teenager Statute, in articles 241-A to 241-E. Article 235 of the Brazilian Military Criminal Code – DL 1.001/69-, however, does incriminate any contact deemed to be libidinous, be it of a homosexual nature or not, made in any location subject to military administration. Since the article is entitled Of pederasty or other libidinous acts, gay rights advocates claim that, since the Brazilian armed forces are composed almost exclusively of males, the article allows for witch-hunts against homosexuals in the military service. This article of the Military Criminal Code is under scrutiny by the Brazilian Supreme Court (ADPF 291).

Canada

Before 1859, the Province of Canada prosecuted sodomy under the English Buggery Act. In 1859, the Province of Canada enacted its own buggery law in the Consolidated Statutes of Canada as an offence punishable by death. Buggery remained punishable by death until 1869. A broader law targeting all homosexual male sexual activity ("gross indecency") was passed in 1892, as part of a larger update to the criminal law of the new dominion of Canada.[29] Changes to the Criminal Code in 1948 and 1961 were used to brand gay men as "criminal sexual psychopaths" and "dangerous sexual offenders." These labels provided for indeterminate prison sentences. Most famously, George Klippert, a homosexual, was labelled a dangerous sexual offender and sentenced to life in prison, a sentence confirmed by the Supreme Court of Canada in 1967.[30] He was released in 1971.

Sodomy was decriminalized after the Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1968-69 (Bill C-150) received royal assent on 27 June 1969. The offences of buggery and "gross indecency" were still in force, however the new act introduced exemptions for married couples, and any two consenting adults above the age of 21 regardless of gender or sexual orientation. The bill had been originally introduced in the House of Commons in 1967 by then Minister of Justice Pierre Trudeau,[31] who famously stated that "there's no place for the state in the bedrooms of the nation".[32]

Revisions to the Criminal Code in 1987 repealed the offence of "gross indecency", changed "buggery" to "anal intercourse" and reduced the age exemption from 21 to 18.[33] Section 159 of the Criminal Code continued to criminalize anal sex in general, with exemptions (provided no more than two people are present) for husbands and wives, and two consenting parties above the age of 18.[34]

Subsequent case law held that section 159 was unconstitutional, thus anal sex was de facto legal between any two or more consenting persons above the age of consent (14). In the 1995 Court of Appeal for Ontario case R. v. M. (C.) the judges ruled that the law was unconstitutional on the basis that the specific exemptions based on marital status and age infringed on the equality rights guaranteed by section 15 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, and constituted discrimination based on sexual orientation.[35] A similar decision was made by the Quebec Court of Appeal in the 1998 case R. v. Roy.[36] In a 2002 decision regarding a case in which three people were engaged in sexual intercourse, the Court of Queen's Bench of Alberta declared section 159 in its entirety to be null, including the provisions criminalizing the act when more than two persons are taking part or present.[37]

NDP MP Joe Comartin introduced private member's bills in 2007 and 2011 to repeal section 159 of the Criminal Code, however neither passed first reading.[38][39]

In June 2019, C-75 passed both houses of the Parliament of Canada and received royal assent, repealing section 159 effective immediately and making the age of consent equal at 16 for all individuals.[40]

Chile

Consensual sex between two same-sex adults was decriminalized in 1999. It is still banned if one of the persons is below the age of 18, even though the age of consent is 14.[41]

China

Sodomy was never explicitly criminalized in China, but private sex between unmarried people was illegal until 1997,[42] and same-sex marriage is not legal in China. The Chinese Supreme Court ruled in 1957 that voluntary sodomy was not a criminal act.[43] Private sex in any form between two consenting adults does not currently violate any laws. However, if someone under 18 is involved, the adult partner will be prosecuted. In a notable case in 2002, a man who had anal intercourse with a teenager was sentenced to three and a half years in prison.

In Hong Kong "Homosexual Buggery" is prohibited. Before 2014, according to the Crimes Ordinance Section 118C,[44] both of the two men must be at least 16 to commit homosexual buggery legally or otherwise both of them can be liable to life imprisonment. Sect 118F states that committing homosexual buggery not privately is also illegal and can be liable to imprisonment for 5 years.

"Heterosexual Buggery". A man who commits buggery with a girl under 21 can also be liable for life imprisonment (Sect 118D) while no similar laws concerning committing heterosexual buggery in private exist.

In 2005, Judge Hartmann found these 4 laws: Sect 118C, 118F, 118H, and 118J were discriminatory towards gay males and unconstitutional under the Hong Kong Basic Law and contrary to the Bill of Rights Ordinance in a judicial review filed by a Hong Kong resident. It was believed that the age of consent had been reduced from 21 to 16 for any kind of homosexual sex acts. In 2014, the ordinance was amended according to the judgement.[45]

Denmark

In 1933 Denmark became the third country in Europe to fully legalize homosexuality. The age of consent has been set at 15 since 1977.

France

Since the Penal Code of 1791, France has not had laws punishing homosexual conduct per se between over-age consenting adults in private. However, other qualifications such as "offense to good mores" were occasionally retained in the 19th century (see Jean Jacques Régis de Cambacérès).

In 1960, a parliamentary amendment by Paul Mirguet added homosexuality to a list of "social scourges", along with alcoholism and prostitution. This prompted the government to increase the penalties for public display of a sex act when the act was homosexual. Transvestites or homosexuals caught cruising were also the target of police repression.

In 1981, the 1960 law making homosexuality an aggravating circumstance for public indecency was repealed. Then in 1982, under president François Mitterrand, the law from 1942 (Vichy France) making the age of consent for homosexual sex higher (18) than for heterosexual sex (15) was also repealed,[46] despite the vocal opposition of Jean Foyer in the National Assembly.[47]

Germany

Paragraph 175, which punished "fornication between men", was eased to an age of consent of 21 in East Germany in 1957 and in West Germany in 1969. This age was lowered to 18 in the East in 1968 and the West in 1973, and all legal distinctions between heterosexual and homosexual acts were abolished in the East in 1988, with this change being extended to all of Germany in 1994 as part of the process of German Reunification.

In modern German, the term Sodomie has a meaning different from the English word "sodomy": it does not refer to anal sex, but acts of Zoophilia. The change occurred mostly in the middle of the 19th century, at least in the last decade of the century. Only the moral theology of the Roman Catholic church changed not until some time after World War II to the term homosexuality.

Gibraltar

In Gibraltar, a British overseas territory, male homosexual acts (but not heterosexual anal sex) have been decriminalised in Gibraltar since 1993, where the age of consent was 18 higher for male homosexual acts. Then under a Supreme Court decision in April 2011, the age of consent became 16, regardless of sexual orientation and/or gender.[48] At the same time, under the same decision heterosexual anal sex was also decriminalised as well.[49] In August 2011, the new gender-neutral Crimes Act 2011 was approved, which sets an equal age of consent of 16 regardless of sexual orientation, and reflects the decision of the Supreme Court in statute.[50]

Hungary

Homosexuality in Hungary was decriminalized in 1962, Paragraph 199 of the Hungarian Penal Code from then on threatened "only" adults over 20 who engaged themselves in a consensual same-sex relationship with an underaged person between 14 and 20. Then in 1978 the age was lowered to 18. Since 2002, by the ruling of the Constitutional Court of Hungary repealed Paragraph 199 – Which provided an equal age of consent of 14, regardless of sexual orientation and/or gender. Since 1996, the Unregistered Cohabitation Act 1995 was provided for any couple, regardless of gender and/or sexual orientation and from 1 July 2009 the Registered Partnership Act 2009 becomes effective, and provides a registered partnership just for same-sex couples – since that opposite-sex already have marriage, this would in-turn create duplication.[51]

Iceland

Homosexuality has been legal in Iceland since 1940, but equal age of consent was not approved until 1992. Civil union was legalised by Alþingi in 1996 with 44 votes pro, 1 con, 1 neutral and 17 not present. Those laws were changed to allow adoption and artificial insemination for lesbians 27 June 2006 among other things. Same-sex marriage was legalised in 2010.

India

On 2 July 2009, in the case of Naz Foundation v National Capital Territory of Delhi, the High Court of Delhi struck down much of S. 377 of the IPC as being unconstitutional. The Court held that to the extent S. 377 criminalised consensual non-vaginal sexual acts between adults, it violated an individual's fundamental rights to equality before the law, freedom from discrimination and to life and personal liberty under Articles 14, 15 and 21 of the Constitution of India. The High Court did not strike down S. 377 completely – it held the section was valid to the extent it related to non-consensual non-vaginal intercourse or to intercourse with minors – and it expressed the hope that Parliament would soon legislatively address the issue.[52]

India does not recognize same-sex unions of any type. On 11 December 2013, the Supreme Court of India overturned the ruling in Naz Foundation v. National Capital Territory of Delhi, effectively re-criminalizing homosexual activity until action was taken by parliament.[53] However, on 12 July 2018, a Constitution bench of the Supreme Court of India started hearing a review petition over its 2013 judgment. Then on 6 September 2018, the Supreme Court struck down the part of S. 377 criminalizing consensual homosexual activities, but upheld that other aspects of S. 377 criminalizing unnatural sex with minors and animals will remain in force.[54]

Iran

Sodomy is illegal in Iran and is punishable by death.

Ireland

In the Republic of Ireland, the Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Act 1993 abolished the offence of "buggery between persons".[55] For some years prior to 1993, criminal prosecution had not been made for buggery between consenting adults. The 1993 Act created an offence of "buggery with a person under the age of 17 years",[56] penalised similar to statutory rape, which also had 17 years as the age of consent. The Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Act 2006 replaced this offence with "defilement of a child", encompassing both "sexual intercourse" and "buggery".[57] Buggery with an animal is still unlawful under Section 69 of the Sexual Offences Act 2003. In 2012, a man was convicted of this offence for supplying a dog in 2008 to a woman who had intercourse with it and died;[58] he received a suspended sentence and was required to sign the sex offender registry, ending his career as a bus driver.[59]

Israel

The State of Israel inherited its sodomy ("buggery") law from the legal code of the British Mandate of Palestine, but it was never enforced against homosexual acts that took place between consenting adults in private. In 1963, the Israeli Attorney-General declared that these laws would not be enforced. However, in certain criminal cases, defendants were convicted of "sodomy" (which includes oral sex), apparently by way of plea bargains; they had originally been indicted for more serious sexual offenses.

In the late 1960s, the Israeli Supreme Court ruled that these laws could not be enforced against consenting adults. Though unenforced, these laws remained in the penal code until 1988, when they were formally repealed by the Knesset. The age of consent for both heterosexuals and homosexuals is 16 years of age.

Italy

In 1786 Pietro Leopoldo of Tuscany, abolishing death penalty for all crimes, became not only the first Western ruler to do so, but also the first ruler to abolish death penalty for sodomy (though this was replaced with other sentences such as terms in prison or of hard labour).

The Code Napoléon made sodomy legal between consenting adults above the legal age of consent in all Italy except in the Kingdom of Sardinia, the Austria-ruled Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia, and the Papal states.

In the newborn (1860) Kingdom of Italy, Sardinia extended its legal code on the whole of Northern Italy, but not in the South, which made homosexual behaviour legal in the South and illegal in the North. However the first Italian penal code (Codice Zanardelli, 1889), decriminalised same-sex intercourse between consenting adults above the legal age of consent for all regions. A law that has not changed since it was enacted.

Japan

In the Meiji Period, sex between men was punishable under the sodomy laws announced in 1872 and revised in 1873. This was changed by laws announced in 1880 (同性愛に関する法と政治). Since that time no further laws criminalizing homosexuality have been passed.

Macau

In Macau, according to the Código Penal de Macau (Penal Code of Macau) Article 166 & 168, committing anal coitus with whomever under the age of 17 is a crime and shall be punished by imprisonment of up to 10 years (committing with whoever under 14) and 4 years (committing with whoever between 14 and 16) respectively.

Malaysia

Sodomy is illegal in Malaysia. The sodomy laws are sometimes enforced using Section 377 of the Penal Code which prohibit carnal intercourse against the order of nature.

Any person who has sexual connection with another person by the introduction of the penis into the anus or mouth of the other person is said to commit carnal intercourse against the order of nature.

The age of consent in Malaysia is 16. Punishment for voluntarily committing carnal intercourse against the order of nature shall be up to twenty years imprisonment and whipping, while punishment for committing the same offence but without consent is punished by no less than five years imprisonment and whipping.[60]

There was the notable case involving Anwar Ibrahim, former Leader of the Opposition and Deputy Prime Minister who was convicted of sodomy crime under Section 377B of the Penal Code. However, it is debatable whether or not the sodomy law can be enforced consistently.

Mauritius

In Mauritius, sodomy is illegal. According to an unofficial translation of Section 250 of the Mauritius Criminal Code of 1838, "Any person who is guilty of the crime of sodomy [...] shall be liable to penal servitude for a term not exceeding 5 years."[61]

New Zealand

New Zealand inherited the United Kingdom's sodomy laws in 1854. The Offences Against The Person Act of 1867 changed the penalty of buggery from execution to life imprisonment for "Buggery". In 1961 in a revision of the Crimes Act, the penalty was reduced to a maximum of 7 years between consenting adult males.

Homosexual sex was legalised in New Zealand as a result of the passing of the Homosexual Law Reform Act 1986. The age of consent was set at 16 years, the same as for heterosexual sex.

Since 4 September 2007 two out of the three territories of New Zealand (Niue and Tokelau) legalized homosexuality with an equal age of consent as well by the Niue Amendment Act 2007. Cook Islands meanwhile still has a sodomy law on the books Crimes Act (1969), s153 and a155.

North Korea

No explicit anti-gay criminal law exists, but government media depicts LGBT people negatively and some gay couples have been executed for being, "against the socialist lifestyle".

Norway

Same-sex sexual activity has been legal in Norway since 1972. At the same time of legalization, the age of consent became equal regardless of gender or sexual orientation, at 16.

Poland

Poland is one of the few countries where homosexuality has never been considered a crime. Forty years after Poland lost its independence, in 1795, the sodomy laws of Russia, Prussia, and Austria came into force in the occupied Polish lands. Poland retained these laws after independence in 1918, but they were never enforced, and were officially abandoned in 1932.

Russia

In the past, in Russia sexual activity between males was criminalized by state law on 4 March 1934. Sexual activity between females was not mentioned in the law. On 27 May 1993, homosexual acts between consenting males were decriminalized.

Serbia

The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia later restricted the offense in 1959 to only apply to homosexual anal intercourse; but with the maximum sentence reduced from 2 to 1 year imprisonment. In 1994, male homosexual sexual intercourse was officially decriminalised in the Republic of Serbia, a part of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. The age of consent was set at 18 years for anal intercourse between males and 14 for other sexual practices. An equal age of consent of 14 was later introduced on 1 January 2006, regardless of sexual orientation or gender.

Singapore

Section 377A of the Singapore Penal Code criminalise "outrage of decency" and additionally punish commission, solicitation, or attempted male same-sex "gross indecency", with imprisonment of up to two years'.[62] Section 377 was added by the British colonial administration in 1858, replacing Hindu law at the time which did not criminalise consensual same-sex activity. In October 2007, Singapore repealed section 377 of the Penal Code and reduced the maximum sentence for male-male sex to a maximum term of 2 years' imprisonment under the maintained section 377A.[63] The section has generally not been enforced, and applications of the section by lower courts have been overturned by the High Court.

South Africa

The common-law crimes of sodomy and "commission of an unnatural sexual act" in South Africa's Roman-Dutch law were declared to be unconstitutional (and therefore invalid) by the Witwatersrand Local Division of the High Court on 8 May 1998 in the case of National Coalition for Gay and Lesbian Equality v Minister of Justice,[64] and this judgment was confirmed by the Constitutional Court on 9 October of the same year.[65] The ruling applied retroactively to acts committed since the adoption of the Interim Constitution on 27 April 1994.[66]

Despite the abolition of sodomy as a crime, the Sexual Offences Act, 1957 set the age of consent for same-sex activities at 19, whereas for opposite-sex activities it was 16. This was rectified by the Criminal Law (Sexual Offences and Related Matters) Amendment Act, 2007, which comprehensively reformed the law on sex offences to make it gender- and orientation-neutral, and set 16 as the uniform age of consent.[67] In 2008, even though the new law had come into effect, the former inequality was retrospectively declared to be unconstitutional in the case of Geldenhuys v National Director of Public Prosecutions.[68]

South Korea

Sexual relationships between members of the same sex are legal under civilian law, but are regarded as sexual harassment in the Military Penal Code.

Sweden

Sweden legalized homosexuality in 1944. The age of consent is 15, regardless of whether the sexual act is heterosexual or homosexual, since equalization in 1978. The Swedish Crime Law (SFS 1962:700), chapter six ('About Sexual Crimes'), shows gender-neutral terms and does not distinguish between sexual orientation.

Taiwan

In Taiwan, the Criminal Code of Republic of China Article 10 officially defines anal intercourse to be a form of sexual intercourse, along with vaginal and oral intercourse. The age of consent is 16, and Article 277 and the Child and Youth Sexual Transaction Prevention Act Article 22 make it a criminal offense to engage in sexual contact with minors. The law is written in gender neutral terms and does not discriminate against homosexual conduct.

Thailand

Anti-sodomy legislation was repealed in Thailand in 1956.[69]

Turkey

In Turkey, homosexual acts had already been decriminalized by its predecessor state, the Ottoman Empire in 1858.[19]

United Kingdom

Sodomy was historically known in England and Wales as buggery, and is usually interpreted as referring to anal intercourse between two males or a male and a female. In England and Wales buggery was made a felony by the Buggery Act of 1533, during the reign of Henry VIII. Section 61 of the Offences against the Person Act 1861, entitled "Sodomy and Bestiality", defined punishments for "the abominable Crime of Buggery, committed either with Mankind or with any Animal". The punishment for those convicted was the death penalty until 1861 in England and Wales, and 1887 in Scotland. James Pratt and John Smith were the last two to be executed for sodomy in 1835. A lesser offence of "attempted buggery" was punished by 2 years of jail and some time on the pillory. In 1885, Parliament enacted the Labouchere Amendment,[70] which prohibited gross indecency between males, a broad term that was understood to encompass most or all male homosexual acts. Following the Wolfenden report, sexual acts between two adult males, with no other people present, were made legal in England and Wales in 1967, in Scotland in 1980, Northern Ireland in 1982, UK Crown Dependencies Guernsey in 1983, Jersey in 1990 and Isle of Man in 1992.

The definition of "buggery" was not specified in these or any statute, but rather established by judicial precedent.[71] Over the years the courts have defined buggery as including either

- anal intercourse or oral intercourse by a man with a man or woman[72] or

- vaginal intercourse by either a man or a woman with an animal,[73]

but not any other form of "unnatural intercourse",[74] the implication being that anal sex with an animal would not constitute buggery. Such a case has not, to date, come before the courts of a common law jurisdiction in any reported decision. In the 1817 case of Rex v. Jacobs, the Crown Court ruled that oral intercourse with a child aged 7 did not constitute sodomy.[74]

At common law consent was not a defence[75] nor was the fact that the parties were married.[76] In the UK, the punishment for buggery was reduced from hanging to life imprisonment by the Offences against the Person Act 1861. As with the crime of rape, buggery required that penetration must have occurred, but ejaculation is not necessary.[77]

.jpg)

Decriminalisation and abolition

In England, the first relaxation of the law came from the Wolfenden Report, published in 1957. The key proposal of the report was that "homosexual behaviour between consenting adults in private should no longer be a criminal offence".[78] However, the law was not changed until 1967, when the Sexual Offences Act 1967 decriminalised consensual "homosexual acts" as long as only two men were involved, both were over 21 and the acts happened in private. The Act concerned acts between men only, and anal sex between men and women remained an offence until 1994.

In the 1980s and 1990s, gay rights organizations made attempts to equalize the age of consent for heterosexual and homosexual activity, which had previously been 21 for homosexual activity but only 16 for heterosexual acts. Efforts were also made to modify the "no other person present" clause so that it dealt only with minors. In 1994, Conservative MP Edwina Currie introduced an amendment to the Criminal Justice and Public Order Bill which would have lowered the age of consent to 16. The amendment failed, but a compromise amendment which lowered the age of consent to 18 was accepted.[79] 1 July 1997 decision in the case Sutherland v. United Kingdom resulted in the Sexual Offences (Amendment) Act 2000 which further reduced it to 16, and the "no other person present" clause was modified to "no minor persons present".

However, it was not until 2000, with the Sexual Offences (Amendment) Act 2000, that the age of consent for anal sex was reduced to 16 for men and women. In 2003, the Sexual Offences Act significantly reformed English law in relation to sexual offences, introducing a new range of offences relating to underage and non-consensual sexual activity that were concerned with the act that occurred, rather than the sex/gender or sexual orientation of those committing it.[80] Buggery in as much as it related to sexual intercourse with animal (bestiality) remained untouched until the Sexual Offences Act 2003, when it was replaced with a new offence of "intercourse with an animal".[80][81]

Today, the universal age of consent is 16 in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. The Sexual Offences (Northern Ireland) Order 2008[82] brought Northern Ireland into line with the rest of the United Kingdom on 2 February 2009 (prior to that, the age of consent for both heterosexuals and homosexuals was 17). The three British Crown dependencies also have an equal age of consent at 16: since 2006, in the Isle of Man; since 2007, in Jersey; and since 2010 in Guernsey.

United States

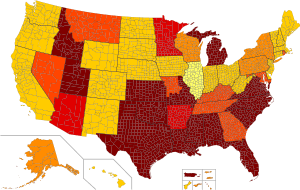

Sodomy laws in the United States were largely a matter of state rather than federal jurisdiction, except for laws governing the U.S. Armed Forces. In the 1950s, all states had some form of law criminalizing sodomy. In the early 1960s, the penalties for sodomy in the various states varied from imprisonment for two to ten years and/or a fine of US$2,000.[83] Illinois became the first American jurisdiction to repeal its law against consensual sodomy in 1961; in 1962, the Model Penal Code recommended all states do so.[84]

In the 1986 Bowers v. Hardwick decision upholding Georgia's sodomy law, the United States Supreme Court ruled that nothing in the United States Constitution bars a state from prohibiting sodomy.

By 2002, 36 states had repealed all sodomy laws or had them overturned by court rulings. In 2003, only 10 states had laws prohibiting all sodomy, with penalties ranging from 1 to 15 years imprisonment. Additionally, four other states had laws that specifically prohibited same-sex sodomy. On June 26, 2003, the U.S. Supreme Court in a 6–3 decision in Lawrence v. Texas struck down the Texas same-sex sodomy law, ruling that this private sexual conduct is protected by the liberty rights implicit in the due process clause of the United States Constitution, with Sandra Day O'Connor's concurring opinion arguing that they violated equal protection. This decision invalidated all state sodomy laws insofar as they applied to noncommercial conduct in private between consenting civilians.

The Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces has ruled that the Lawrence v. Texas decision applies to Article 125 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice, which is a ban on sodomy in the U.S. Armed Forces. In both United States v. Stirewalt and United States v. Marcum, the court ruled that the "conduct falls within the liberty interest identified by the Supreme Court",[85] but went on to say that despite the application of Lawrence to the military, Article 125 can still be upheld in cases where there are "factors unique to the military environment" that would place the conduct "outside any protected liberty interest recognized in Lawrence."[86] Examples of such factors could be fraternization, public sexual behavior, or any other factors that would adversely affect good order and discipline.[86] Convictions for consensual sodomy have been overturned in military courts under the Lawrence precedent in both United States v. Meno.[87] and United States v. Bullock.[88]

As of 2014, 12 states still had laws against consensual sodomy; in 2013 police in East Baton Rouge Parish, Louisiana arrested gay men for "attempted crimes against nature" despite the law having been ruled unconstitutional and unenforcable.[89]

Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe's Former President Robert Mugabe has waged a violent campaign against homosexuals, claiming that before colonization, Zimbabweans did not engage in homosexual acts.[90] His first major public condemnation of homosexuality came during the Zimbabwe International Book Fair in August 1995.[91] He told the audience that homosexuality:

...Degrades human dignity. It's unnatural and there is no question ever of allowing these people to behave worse than dogs and pigs. If dogs and pigs do not do it, why must human beings? We have our own culture, and we must re-dedicate ourselves to our traditional values that make us human beings... What we are being persuaded to accept is sub-animal behaviour and we will never allow it here. If you see people parading themselves as lesbians and gays, arrest them and hand them over to the police![92]

In September 1995, Zimbabwe's parliament introduced legislation banning homosexual acts.[91] In 1997, a court found Canaan Banana, Mugabe's predecessor and the first President of Zimbabwe, guilty of 11 counts of sodomy and indecent assault.[93] Banana's trial proved embarrassing for Mugabe, when Banana's accusers alleged that Mugabe knew about Banana's conduct and had done nothing to stop it.[94] Regardless, Banana fled Zimbabwe only to return in 1999 and served one year in prison for his homosexual acts. Banana was also stripped of his priesthood.

See also

- Zoophilia and the law

- Homophobia

- LGBT rights by country

- Timeline of LGBT history in Britain

- Societal attitudes towards homosexuality

- Utrecht sodomy trials

Notes

- These sub-national jurisdictions are: the provinces of Aceh and South Sumatra (Indonesia), the Cook Islands (New Zealand), Gaza (Palestine) and Chechnya (Russia).

- Legal nationwide, except the provinces of Aceh and for Muslims in the city of Palembang in South Sumatra.

References

- Weeks, Jeff (January 1981). Sex, Politics and Society: The Regulation of Sexuality Since 1800. London: Longman Publishing Group. ISBN 0-582-48334-4.

- Shirelle Phelps (2001). World of Criminal Justice: N-Z. Gale Group. p. 686. ISBN 0787650730. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- John Scheb, John Scheb, II (2013). Criminal Law and Procedure. Cengage Learning. p. 185. ISBN 978-1285546131. Retrieved 13 January 2014.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- David Newton (2009). Gay and Lesbian Rights: A Reference Handbook, Second Edition. ABC-CLIO. p. 85. ISBN 978-1598843071. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- Sullivan, Andrew (24 March 2003). "Unnatural Law". The New Republic. Retrieved 27 November 2009.

Since the laws had rarely been enforced against heterosexuals, there was no sense of urgency about their repeal.

(Or Sullivan, Andrew (24 March 2003). "Unnatural Law". The New Republic. 228 (11).) - [https://ilga.org/downloads/ILGA_State_Sponsored_Homophobia_2019.pdf; updates from LGBT rights by country or territory.

- https://76crimes.com/76-countries-where-homosexuality-is-illegal/

- https://www.washingtonblade.com/2020/07/08/gabon-formally-decriminalizes-homosexuality/

- "The Code of the Assura, c. 1075 BCE". Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- Thomas A.J. McGinn, Prostitution, Sexuality and the Law in Ancient Rome (Oxford University Press, 1998), pp. 140–141; Amy Richlin, The Garden of Priapus: Sexuality and Aggression in Roman Humor (Oxford University Press, 1983, 1992), pp. 86, 224; John Boswell, Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality: Gay People in Western Europe from the Beginning of the Christian Era to the Fourteenth Century (University of Chicago Press, 1980), pp. 63, 67–68; Craig Williams, Roman Homosexuality: Ideologies of Masculinity in Classical Antiquity (Oxford University Press, 1999), p. 116.

- James L. Butrica, "Some Myths and Anomalies in the Study of Roman Sexuality," in Same-Sex Desire and Love in Greco-Roman Antiquity and in the Classical Tradition (Haworth Press, 2005), p. 231.

- Amy Richlin, The Garden of Priapus: Sexuality and Aggression in Roman Humor (Oxford University Press, 1983, 1992), p. 225, and "Not before Homosexuality: The Materiality of the cinaedus and the Roman Law against Love between Men," Journal of the History of Sexuality 3.4 (1993), p. 525.

- Eskridge, William N. (2009). Gaylaw: Challenging the Apartheid of the Closet. Harvard University Press. p. 161. ISBN 9780674036581.

- "Affirming Denominations". Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- John Boswell, Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality (1980) p. 293.

- "Book the Fourth – Chapter the Fifteenth: Of Offences Against the Persons of Individuals". Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England. Archived from the original on 7 September 2006. Retrieved 6 August 2006.

- Beyond Carnival. Green, James. The University of Chicago Press. 1999. (in Portuguese)

- Ishtiaq Hussain (15 February 2011). "The Tanzimat: Secular Reforms in the Ottoman Empire" (PDF). Faith Matters.

- "Where is it illegal to be gay?". BBC News. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- Hazard, John N. (1965). "Unity and Diversity in Socialist Law". Law and Contemporary Problems. Duke Law. 30 (2): 270–290. doi:10.2307/1190515. JSTOR 1190515.

- West, Green. Sociolegal Control of Homosexuality: A Multi-Nation Comparison. p. 224.

-

Soviet legislation does not recognize so-called crimes against morality. Our laws proceed from the principle of protection of society and therefore countenance punishment only in those instances when juveniles and minors are the objects of homosexual interest ... while recognizing the incorrectness of homosexual development ... our society combines prophylactic and other therapeutic measures with all the necessary conditions for making the conflicts that afflict homosexuals as painless as possible and for resolving their typical estrangement from society within the collective

- —Sereisky, Great Soviet Encyclopedia, 1930, p. 593

- Himl, Pavel. "Oponentský posudek rigorózní práce Jana Seidla "Úsilí o odtrestnění homosexuality za první republiky"". Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- https://ilga.org/downloads/ILGA_State_Sponsored_Homophobia_2019.pdf

- "RIW Survey.indd" (PDF). Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- Carbery, Graham (2010). "Towards Homosexual Equality in Australian Criminal Law: A Brief History" (PDF) (2nd ed.). Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives Inc.

- "RELATIONSHIPS ACT 2003". Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- Burke, Gail (15 September 2016). "Queensland lowers anal sex consent age to 16, ending 'archaic' law". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 17 September 2016.

- Criminal Code, 1892, SC 1892, c 29

- "Klippert v. The Queen – SCC Cases (Lexum)".

- Journals of the House of Commons, CXV, 1968–69

- Pierre Trudeau (21 December 1967). The CBC Digital Archives Website. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 15 April 2008.

- An Act to amend the Criminal Code and the Canada Evidence Act, R.S.C. 1985 (3d Supp.), c. 19.

- "Criminal Code (R.S.C., 1985, c. C-46)". Department of Justice Canada. 23 April 2012. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- "Ontario Youth Sodomy Law Ruling". Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- "CanLII – 1998 CanLII 12775 (QC CA)". Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- "R. v. Roth, 2002 ABQB 145 (CanLII)". Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- "Bill C-438: An Act to amend the Criminal Code (consent)". 2 May 2007. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- "Bill C-628: An Act to amend the Criminal Code (consent)". 11 February 2011. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- "Bill C-75". bill of 21 June 2019. Parliament of Canada.

- http://web.derecho.uchile.cl/cej/rej14/ABR%20VVAA%20_4_x.pdf

- Tania Branigan. "For Chinese women, unmarried motherhood remains the final taboo". the Guardian. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- "最高人民法院关于成年人间自愿鸡奸是否犯罪问题的批复_全文". www.law-lib.com. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- CRIMES ORDINANCE, Chapter 200, Section 118C, Homosexual buggery with or by man under 21, hklii.hk

- "Statute Law (Miscellaneous Provisions) Ordinance 2014". Elegislation.gov.hk. 1 January 1970. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- "Fac-similé JO du 05/08/1982, page 02502 – Legifrance". Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- Proceedings of the National assembly, 2nd sitting of 20 December 1981

- "Judge rules: age of consent is 16 for all". Gibraltar Chronicle. 9 April 2011. Archived from the original on 27 March 2012.

- "Sex debate women's group demands referendum in bid to raise consent age". Gibraltar Chronicle. 12 April 2011. Archived from the original on 27 March 2012.

- "Age of consent, 16, framed in law". Gibraltar Chronicle. 20 August 2011. Archived from the original on 3 November 2013.

- "UK Gay News – Gay and Lesbian Marriage, Partnership or Unions Worldwide". Archived from the original on 12 September 2009.

- Yuvraj Joshi (21 July 2009). "A New Law for India's Sexual Minorities". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- Venkatesan, J. (11 December 2013). "Homosexuality illegal: SC". The Hindu. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- Rautray, Samanwaya (6 September 2018). "Section 377: SC rewrites history, homosexual behaviour no longer a crime". The Economic Times. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Act, 1993; §2: Abolition of offence of buggery between persons. Irish Statute Book.

- Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Act, 1993; §3: Buggery of persons under 17 years of age. Irish Statute Book.

- Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Act 2006 §§1,2,3 and Schedule. Irish Statute Book.

- Sheridan, Anne (8 November 2012). "Court told mother died after acting on 'sexual fantasy'". Limerick Leader. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- "Bus driver avoids prison in bestiality case". Limerick Post. 19 December 2012. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- Tatchell, Peter (26 November 2009). "A Commonwealth of homophobes". Guardian. Retrieved 27 November 2009.

- "State-sponsored Homophobia: A world survey of laws prohibiting same sex activity between consenting adults", International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association, authored by Lucas Paoli Itaborahy and Jingshu Zhu, May 2013, page 51 Archived 19 July 2013 at WebCite

- "gay.com Daily". Gaywired.com. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- "GenerationQ.net – News, Entertainment, Lifestyle and Opinion for GLBT Australia, USA, Canada, UK, Europe, Asia and South America". Archived from the original on 26 October 2007.

- "South African Court Ends Sodomy Laws". The New York Times. 8 May 1998. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- McNeil, Donald G. (9 October 1998). "South Africa Strikes Down Laws on Gay Sex". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- Reber, Pat (9 October 1998). "South Africa Court Upholds Gay Rights". Associated Press. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- Tolsi, Niren (11 January 2008). "Is it the kiss of death?". Mail & Guardian. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- "Consent judgment welcomed". News24. Sapa. 26 November 2008. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- Shivananda Khan, "Assessment of sexual health needs of males who have sex with males in Laos and Thailand". (425 KB), Naz Foundation International, February 2005

- "The Law in England, 1290–1885". Retrieved 6 August 2006.

- Quintin Hogg, Baron Hailsham of St Marylebone (ed.). Halsbury's Laws of England. 11 (4th ed.). p. 505.

- R v Wiseman (1718) Fortes Rep 91.

- R v Bourne (1952) 36 Cr App R 135; Sir Edward Coke also reports "... a great lady had committed buggery with a baboon and conceived by it..." at 3 Inst 59.

- Russell, Sir William Oldnall (1825). Crown cases reserved for consideration: and decided by the Twelve judges of England, from the year 1799 to the year 1824. pp. 331–332.

- Because consent was not required, heavier penalties require proof of lack of consent – see R v Sandhu [1997] Crim LR 288; R v Davies [1998] 1 Cr App R (S) 252.

- R v Jellyman (1838) 8 C & P 604.

- R v Reekspear (1832) 1 Mood CC 342; R v Cozins (1834) 6 C & P 351; the Offences against the Person Act 1861, §63.

- "The Cabinet Papers". The National Archives. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- "Amendment Of Law Relating To Sexual Acts Between Men". Hansard. Parliament of the United Kingdom. 21 February 1994. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- Johnson, Paul. Buggery and Parliament, 1533–2017. SSRN 3155522.

- "Section 69, Sexual Offences Act 2003". Legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- "Sexual Offences (Northern Ireland) Order 2008 (Commencement) Order 2008". Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- Gilleland, Don (3 January 2013). "50 years of change". Florida Today. Melbourne, Florida. pp. 9A.

- Canaday, Margot (3 September 2008). "We Colonials: Sodomy Laws in America". The Nation. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- U.S. Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces: U.S. v. Stirewalt, 29 September 2004. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

- U.S. Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces: U.S. v. Marcum, 23 August 2004. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

- United States v. Meno, United States Court of Criminal Appeals Archived 2008-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- SodomyLaws.org: US v. Bullock (2004). Retrieved 16 August 2010.

- "12 states still ban sodomy a decade after court ruling". USA TODAY. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- Page 213 Encyclopedia of Sex and Gender: Men and Women in the World's Cultures

- Page 180 Hungochani: The History of a Dissident Sexuality in Southern Africa

- Under African Skies, Part I: 'Totally unacceptable to cultural norms' Archived 6 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine Kaiwright.com

- Page 93 Body, Sexuality, and Gender v. 1

- Canaan Banana, president jailed in sex scandal, dies The Guardian

Sources

- David Bianco, First Sodomy Laws in the American Colonies

- Daniel Ottosson, International Lesbian and Gay Association, "With the Government in Our Bedrooms: A Survey on the Laws Over the World Prohibiting Consenting Adult Sexual Same-Sex Acts" (Nov. 2006)

- International Lesbian and Gay Association, "World Legal Wrap-Up" (Nov. 2006)

Further reading

- Graham Willett, Living out Loud: A History of Gay and Lesbian Activism in Australia, 2000. ISBN 1-86448-949-9.

- Peter McWilliams, Ain't Nobody's Business If You Do, 1998. ISBN 0-931580-58-7.

- International Human Rights Law and the Criminalization of Same-Sex Sexual Conduct, International Commission of Jurists, 2010

- Steve Hail, "My Secret Service – A gay man in the REME"

- Paul Johnson "Buggery and Parliament, 1533–2017".

- Smith & Hogan, Criminal Law (10th ed), ISBN 0-406-94801-1

- Paul Johnson "Buggery and Parliament, 1533–2017".