War in Darfur

The War in Darfur, also nicknamed the Land Cruiser War,[lower-alpha 1] is a major armed conflict in the Darfur region of Sudan that began in February 2003 when the Sudan Liberation Movement (SLM) and the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) rebel groups began fighting the government of Sudan, which they accused of oppressing Darfur's non-Arab population.[27][28] The government responded to attacks by carrying out a campaign of ethnic cleansing against Darfur's non-Arabs. This resulted in the death of hundreds of thousands of civilians and the indictment of Sudan's president, Omar al-Bashir, for genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity by the International Criminal Court.[29]

| War in Darfur | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Sudanese Civil Wars | ||||||||

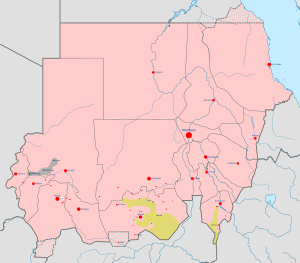

Military situation in Sudan on 6 June 2016. (Darfur on the far left) Under control of the Sudanese Government and allies

For a more detailed map of the current military situation in Sudan, see here. | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||

|

SARC (from 2014)

Supported by: |

Janjaweed |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||

|

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | ||||||||

|

|

| No specific units | ||||||

| Strength | ||||||||

|

SRF: 60,000

|

SAF: 109,300[c]

|

UNAMID: 15,845 soldiers and 3,403 police officers[20] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | ||||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | 235 killed[21] | ||||||

|

Total killed: Total displaced: 450,000 (Sudanese government estimate) | ||||||||

|

a Known as the National Redemption Front prior to 2011. | ||||||||

| War in Darfur |

|---|

|

|

| Combatants |

| Other articles |

|

One side of the conflict is mainly composed of the Sudanese military, police and the Janjaweed, a Sudanese militia group whose members are mostly recruited among Arabized indigenous Africans and a small number of Bedouin of the northern Rizeigat; the majority of other Arab groups in Darfur remained uninvolved.[30] The other side is made up of rebel groups, notably the SLM/A and the JEM, recruited primarily from the non-Arab Muslim Fur, Zaghawa, and Masalit ethnic groups. The African Union and the United Nations also have a joint peacekeeping mission in the region, named UNAMID. Although the Sudanese government publicly denies that it supported the Janjaweed, evidence supports claims that it provided financial assistance and weapons and coordinated joint attacks, many against civilians.[31][32] Estimates of the number of human casualties range up to several hundred thousand dead, from either combat or starvation and disease. Mass displacements and coercive migrations forced millions into refugee camps or across the border, creating a humanitarian crisis. Former US Secretary of State Colin Powell described the situation as a genocide or acts of genocide.[33]

The Sudanese government and the JEM signed a ceasefire agreement in February 2010, with a tentative agreement to pursue peace. The JEM has the most to gain from the talks and could see semi-autonomy much like South Sudan.[34] However, talks were disrupted by accusations that the Sudanese army launched raids and air strikes against a village, violating the Tolu agreement. The JEM, the largest rebel group in Darfur, vowed to boycott negotiations.[35]

The August 2019 Draft Constitutional Declaration, signed by military and civilian representatives during the Sudanese Revolution, requires that a peace process leading to a peace agreement be made in Darfur and other regions of armed conflict in Sudan within the first six months of the 39-month transition period to democratic civilian government.[36][37]

| List of abbreviations used in this article AU: African Union |

Origins of the conflict

Darfur, Arabic for "the home of the Fur", was not a traditional part of the states organized along the upper Nile valley but instead organized as an independent sultanate in the 14th century. Owing to the migration of the Banu Hilal tribe in the 11th century AD, the peoples of the Nile valley became heavily Arabicized while the hinterlands remained closer to native Sudanese cultures. It was first annexed to the Egyptian Sudan in 1875 and then surrendered by its governor Slatin Pasha to the Mahdia in 1883. Following the Anglo-Egyptian victory in the Mahdist War, Sultan Ali Dinar was reinstated as a British client before being deposed by a 1916 expedition after he made overtures in favor of Turkey amid the First World War. Subsequently, Darfur remained a province of the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan and the independent Republic of the Sudan.

There are several different explanations for the origins of the present conflict. One explanation involves the land disputes between semi-nomadic livestock herders and those who practice sedentary agriculture.[38] Water access has also been identified as a major source of the conflict.[39] The Darfur crisis is also related to a second conflict. In southern Sudan, civil war has raged for decades between the northern, Arab-dominated government and Christian and animist black southerners. Yet another origin is conflict between the Islamist, Khartoum-based national government and two rebel groups based in Darfur: the Sudan Liberation Army and the Justice and Equality Movement.[40]

Allegations of apartheid

In early 1991, non-Arabs of the Zaghawa tribe of Sudan attested that they were victims of an intensifying Arab apartheid campaign, segregating Arabs and non-Arabs.[41] Sudanese Arabs, who controlled the government, were widely referred to as practicing apartheid against Sudan's non-Arab citizens. The government was accused of "deftly manipulat(ing) Arab solidarity" to carry out policies of apartheid and ethnic cleansing.[42]

American University economist George Ayittey accused the Arab government of Sudan of practicing racism against black citizens.[43] According to Ayittey, "In Sudan... the Arabs monopolized power and excluded blacks – Arab apartheid."[44] Many African commentators joined Ayittey in accusing Sudan of practising Arab apartheid.[45]

Alan Dershowitz labeled Sudan an example of a government that "actually deserve(s)" the appellation "apartheid".[46] Former Canadian Minister of Justice Irwin Cotler echoed the accusation.[47]

Timeline

Beginning

Flint and de Waal marked the onset of the genocide on February 26, 2003, when a group calling itself the Darfur Liberation Front (DLF) publicly claimed credit for an attack on Golo, the headquarters of Jebel Marra District. Prior to this attack, however, conflict had broken out, as rebels attacked police stations, army outposts and military convoys and the government engaged in a massive air and land assault on the rebel stronghold in the Marrah Mountains. The rebels' first military action was a successful attack on an army garrison on February 25, 2002. The government had been aware of a unified rebel movement since an attack on the Golo police station in June, 2002. Flint and de Waal date the beginning of the rebellion to July 21, 2001, when a group of Zaghawa and Fur met in Abu Gamra and swore oaths on the Qur'an to work together to defend against government-sponsored attacks on their villages.[48] Nearly all of Darfur's residents are Muslim, including the Janjaweed, as well as government leaders in Khartoum.[49]

On March 25, 2003, the rebels seized the garrison town of Tine along the Chadian border, seizing large quantities of supplies and arms. Despite a threat by President Omar al-Bashir to "unleash" the army, the military had little in reserve. The army was already deployed in both the south, where the Second Sudanese Civil War was drawing to an end, and the east, where rebels sponsored by Eritrea were threatening a newly constructed pipeline from the central oilfields to Port Sudan. The rebel guerilla tactic of hit-and-run raids proved almost impossible for the army, untrained in desert operations, to counter. However, its aerial bombardment of rebel positions on the mountain was devastating.[50]

At 5:30 am on April 25, 2003, the Darfur genocide arose when the Sudan Liberation Movement and the JEM, which is the largest rebel group in Darfur, entered Al-Fashir, the capital city of North Darfur and attacked the sleeping garrison. In the next four hours, four Antonov bombers and helicopter gunships (according to the government; seven according to the rebels) were destroyed on the ground, 75 soldiers, pilots and technicians were killed and 32 were captured, including the commander of the air base, a Major General. The success of the raid was unprecedented in Sudan; in the twenty years of the war in the south, the rebel Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA) had never before carried out such an operation.[51]

The Al-Fashir raid was a turning point, both militarily and psychologically. The armed forces had been humiliated by the raid, placing the government in a difficult strategic situation. The incompetent armed forces needed to be retrained and redeployed amid concerns about the loyalty of the many Darfurian non-commissioned officers and soldiers. Responsibility for prosecuting the war was given to Sudanese military intelligence. Nevertheless, in the middle months of 2003, rebels won 34 of 38 engagements. In May, the SLA destroyed a battalion at Kutum, killing 500 and taking 300 prisoners; in mid-July, 250 were killed in a second attack on Tine. The SLA began to infiltrate farther east, threatening to extend the war into Kordofan.

Given that the army was consistently losing, the war effort switched to emphasize three elements: military intelligence, the air force and the Janjaweed. The latter were armed Baggara herders whom the government had used to suppress a Masalit uprising from 1986 to 1999. The Janjaweed became the center of the new counter-insurgency strategy. Though the government consistently denied supporting them, military resources were poured into Darfur and the Janjaweed were outfitted as a paramilitary force, complete with communication equipment and some artillery. The military planners were aware of the probable consequences of such a strategy: similar methods undertaken in the Nuba Mountains and around the southern oil fields during the 1990s had resulted in massive human rights violations and forced displacements.[52]

2004–2005

In 2004, Chad brokered negotiations in N'Djamena, leading to the April 8 Humanitarian Ceasefire Agreement between the Sudanese government, the JEM, and the SLA. One group that did not participate in the April cease-fire talks or agreement, the National Movement for Reform and Development, split from the JEM in April. Janjaweed and rebel attacks continued despite the ceasefire, and the African Union (AU) formed a Ceasefire Commission (CFC) to monitor its observance.

In August, the African Union sent 150 Rwandan troops to protect the ceasefire monitors. However, it soon became apparent that 150 troops would not be enough, and they were subsequently joined by 150 Nigerian troops.

On 18 September, the United Nations Security Council issued Resolution 1564 declaring that the Sudan government had not met its commitments and expressing concern at helicopter attacks and assaults by the Janjaweed. It welcomed the intention of the African Union to enhance its monitoring mission and urged all member states to support such efforts.

During April, 2005, after the Sudan government signed a ceasefire agreement with Sudan People's Liberation Army which led to the end of the Second Sudanese Civil War, the African Union Mission in Sudan (AMIS) force was increased by 600 troops and 80 military observers. In July, the force was increased by about 3,300 (with a budget of 220 million dollars). In April, 2005, AMIS was increased to about 7,000.

The scale of the crisis led to warnings of an imminent disaster, with United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan warning about the risk of genocide. The scale of the Janjaweed campaign led to comparisons with the Rwandan genocide, a parallel denied by the Sudanese government. Independent observers noted that the tactics, which included dismemberment and killing of noncombatants, including young children and infants, were more akin to the ethnic cleansing used in the Yugoslav wars and warned that the region's remoteness meant that hundreds of thousands of people were effectively cut off from aid. The Brussels-based International Crisis Group had reported in May 2004 that over 350,000 people could potentially die as a result of starvation and disease.[53]

On 10 July 2005, Ex-SPLA leader John Garang was sworn in as Sudan's vice-president.[54] However, on 30 July, Garang died in a helicopter crash.[55] Despite improved security, talks between the various rebels in the Darfur region progressed slowly.

An attack on the Chadian town of Adré near the Sudanese border led to the death of 300 rebels in December. Sudan was blamed for the attack, which was the second in the region in three days.[56] Escalating tensions led the government of Chad to declare its hostility toward Sudan and to call for Chadians to mobilise against the "common enemy".[57] (See Chad-Sudan conflict)

2006

.jpg)

On 5 May 2006, the Sudanese government signed the Darfur Peace Agreement[58] along with the faction of the SLA led by Minni Minnawi. However, the agreement was rejected by the smaller Justice and Equality Movement and a rival faction of the SLA led by Abdul Wahid al Nur.[32][59] The accord was orchestrated by chief negotiator Salim Ahmed Salim (working on behalf of the African Union), U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Robert B. Zoellick, AU representatives and other foreign officials operating in Abuja, Nigeria.

The 115-page agreement included agreements on national and state power-sharing, demilitarization of the Janjaweed and other militias, an integration of SLM/A and JEM troops into the Sudanese Armed Forces and police, a system of federal wealth-sharing for the promotion of Darfurian economic interests, a referendum on the future status of Darfur and measures to promote the flow of humanitarian aid.[32][60]

Representatives of the African Union, Nigeria, Libya, the US, the UK, the UN, the EU, the Arab League, Egypt, Canada, Norway and the Netherlands served as witnesses.[32]

July and August 2006 saw renewed fighting, international aid organizations considering leaving due to attacks against their personnel. Annan called for 18,000 international peacekeepers in Darfur to replace the 7,000-man AMIS force.[61][62] In one incident at Kalma, seven women, who ventured out of a refugee camp to gather firewood, were gang-raped, beaten and robbed by the Janjaweed. When they had finished, the attackers stripped them naked and jeered at them as they fled.[63]

In a private meeting on 18 August, Hédi Annabi, Assistant Secretary-General for Peacekeeping Operations, warned that Sudan appeared to be preparing for a major military offensive.[64] The warning came a day after UN Commission on Human Rights special investigator Sima Samar stated that Sudan's efforts remained poor despite the May Agreement.[65] On 19 August, Sudan reiterated its opposition to replacing AMIS with a UN force,[66] resulting in the US issuing a "threat" to Sudan over the "potential consequences".[67]

On 25 August, Sudan rejected attending a United Nations Security Council (UNSC) meeting to explain its plan to send 10,000 Sudanese soldiers to Darfur instead of the proposed 20,000 UN peacekeeping force.[68] The Security Council announced it would hold the meeting despite Sudan's absence.[69] Also on 24 August, the International Rescue Committee reported that hundreds of women were raped and sexually assaulted around the Kalma refugee camp during the previous several weeks[70] and that the Janjaweed were reportedly using rape to cause women to be humiliated and ostracised by their own communities.[71] On 25 August, the head of the U.S. State Department's Bureau of African Affairs, Assistant Secretary Jendayi Frazer, warned that the region faced a security crisis unless the UN peacekeeping force deployed.[72]

On 26 August, two days before the UNSC meeting and Frazer was due to arrive in Khartoum, Paul Salopek, a U.S. National Geographic Magazine journalist, appeared in court in Darfur facing charges of espionage; he had crossed into the country illegally from Chad, circumventing the Sudanese government's official restrictions on foreign journalists. He was later released after direct negotiation with President al-Bashir.[73] This came a month after Tomo Križnar, a Slovenian presidential envoy, was sentenced to two years in prison for spying.[74]

Proposed UN peacekeeping force

On 31 August 2006, the UNSC approved a resolution to send a new peacekeeping force of 17,300 to the region.[75] Sudan expressed strong opposition to the resolution. [76] On 1 September, African Union officials reported that Sudan had launched a major offensive in Darfur, killing more than 20 people and displacing over 1,000.[77] On 5 September, Sudan asked the existing AU force to leave by the end of the month, adding that "they have no right to transfer this assignment to the United Nations or any other party. This right rests with the government of Sudan."[78] On 4 September, in a move not viewed as surprising, Chad's president Idriss Déby voiced support for the UN peacekeeping force.[79] The AU, whose mandate expired on 30 September 2006, confirmed that AMIS would leave.[80] The next day, however, a senior US State Department official told reporters that the AU force might remain past the deadline.[81]

Autumn

On 8 September, António Guterres, head of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, said Darfur faced a "humanitarian catastrophe".[82] On 12 September, Sudan's European Union envoy Pekka Haavisto claimed that the Sudanese army was "bombing civilians in Darfur".[83] A World Food Programme official reported that food aid had been blocked from reaching at least 355,000 people.[84] Annan said, "the tragedy in Darfur has reached a critical moment. It merits this council's closest attention and urgent action."[85]

On 14 September, the leader of the Sudan Liberation Movement, Minni Minnawi, stated that he did not object to the UN peacekeeping force, rejecting the Sudanese government's view that such a deployment would be an act of Western invasion. Minnawi claimed that AMIS "can do nothing because the AU mandate is very limited".[86] Khartoum remained opposed to UN involvement, with Al-Bashir depicting it as a colonial plan and stating that "we do not want Sudan to turn into another Iraq."[87]

On 2 October the AU announced that it would extend its presence until 31 December 2006.[88][89] Two hundred UN troops were sent to reinforce the AU force.[90] On 6 October, the UNSC voted to extend the mandate of the United Nations Mission in Sudan until 30 April 2007.[91] On 9 October, the Food and Agriculture Organization listed Darfur as the most pressing food emergency out of the forty countries listed on its Crop Prospects and Food Situation report.[92] On 10 October, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Louise Arbour, claimed that the Sudanese government had prior knowledge of attacks by Janjaweed militias in Buram, South Darfur the month before, in which hundreds of civilians were killed.[93]

On 12 October, Nigerian Foreign Minister Joy Ogwu arrived in Darfur for a two-day visit. She urged the Sudanese government to accept the UN proposal. Nigerian President Olusegun Obasanjo spoke against "stand[ing] by and see[ing] genocide taking place in Darfur."[94] On 13 October, US President George W. Bush imposed further sanctions against those deemed complicit in the atrocities under the Darfur Peace and Accountability Act of 2006. The measures were said to strengthen existing sanctions by prohibiting US citizens from engaging in oil-related transactions with Sudan (although US companies had been prohibited from doing business with Sudan since 1997), freezing the assets of complicit parties and denying them entry to the US.[95]

The lack of funding and equipment for the AU mission meant that the work of aid workers in Darfur was severely limited by fighting. Some warned that the humanitarian situation could deteriorate to levels seen in 2003 and 2004, when UN officials called Darfur the world's worst humanitarian crisis.[88]

On 22 October, the Sudan government told UN envoy Jan Pronk to leave the country within three days. Pronk, the senior UN official in the country, had been heavily criticized by the Sudanese army after he posted a description of several recent military defeats in Darfur to his personal blog.[96] On 1 November, the US announced that it would formulate an international plan which it hoped the Sudanese government would find more palatable.[97] On 9 November, senior Sudanese presidential advisor Nafie Ali Nafie told reporters that his government was prepared to start unconditional talks with the National Redemption Front (NRF) rebel alliance, but noted he saw little use for a new peace agreement. The NRF, which had rejected the May Agreement and sought a new peace agreement, did not comment.[98]

In late 2006, Darfur Arabs started their own rebel group, the Popular Forces Troops, and announced on 6 December that they had repulsed an assault by the Sudanese army at Kas-Zallingi the previous day. They were the latest of numerous Darfur Arab groups to oppose the government since 2003, some of which had signed political accords with rebel movements.

The same period saw an example of a tribe-based split within the Arab forces, when relations between the farming Terjem and nomadic, camel-herding Mahria tribes became tense. Terjem leaders accused the Mahria of kidnapping a Terjem boy, while Mahria leaders said the Terjem had been stealing their animals. Ali Mahamoud Mohammed, the wali, or governor, of South Darfur, said the fighting began in December when the Mahria drove their camels south in a seasonal migration, trampling through Terjem territory near the Bulbul River. Fighting resumed in July 2007.[99]

Proposed compromise UN force and Sudanese offensive

On 17 November reports of a potential deal to place a "compromise peacekeeping force" in Darfur were announced,[100] but would later appear to have been rejected by Sudan.[101] The UN claimed on 18 November that Sudan had agreed to the deployment of UN peacekeepers.[102] Sudan's Foreign Minister Lam Akol stated that "there should be no talk about a mixed force" and that the UN's role should be restricted to technical support. Also on 18 November, the AU reported that Sudanese military and Sudanese-backed militias had launched a ground and air operation in the region that resulted in about 70 civilian deaths. The AU stated that this "was a flagrant violation of security agreements".[103]

On 25 November a spokesperson for UN High Commissioner for Human Rights accused the Sudanese government of having committed "a deliberate and unprovoked attack" against civilians in Sirba on 11 November, which claimed the lives of at least 30 people. The Commissioner's statement maintained that "contrary to the government's claim, it appears that the Sudanese Armed Forces launched a deliberate and unprovoked attack on civilians and their property in Sirba," and that this also involved "extensive and wanton destruction and looting of civilian property".[104]

2007

According to the Save Darfur Coalition, New Mexico Governor Bill Richardson and al-Bashir agreed to a cease-fire whereby the Sudanese "government and rebel groups will cease hostilities for a period of 60 days while they work towards a lasting peace."[105] In addition, the Save Darfur press release stated that the agreement "included a number of concessions to improve humanitarian aid and media access to Darfur." Despite the formality of a ceasefire there have been further media reports of killings and other violence.[106][107] On Sunday 15 April 2007, African Union peacekeepers were targeted and killed.[108] The New York Times reported that "a confidential United Nations report says the government of Sudan is flying arms and heavy military equipment into Darfur in violation of Security Council resolutions and painting Sudanese military planes white to disguise them as United Nations or African Union aircraft."[109]

On 31 March 2007 Janjaweed militiamen killed up to 400 people in the eastern border region of Chad near Sudan. The border villages of Tiero and Marena were encircled and then fired upon. The women were robbed and the men shot according to the UNHCR. Many of those who survived the initial attack, ended up dying due to exhaustion and dehydration, often while fleeing.[110] On 14 April 2007, more attacks were reported by the UNHCR in Tiero and Marena.[111]

On 18 April President Bush gave a speech at the US Holocaust Memorial Museum criticizing the Sudanese government and threatened further sanctions if the situation did not improve.[112]

Sudan's humanitarian affairs minister, Ahmed Haroun, and a Janjaweed militia leader, known as Ali Kushayb, were charged by the International Criminal Court with 51 counts of war crimes and crimes against humanity. Ahmed Haroun said he "did not feel guilty," his conscience was clear, and that he was ready to defend himself.[113]

Al-Bashir and Deby signed a peace agreement on 3 May 2007 aimed at reducing tension between their countries.[114] The accord was brokered by Saudi Arabia. It asserted that neither country would harbor, train or fund armed movements opposed to the other. Reuters reported that "Deby's fears that Nouri's UFDD may have been receiving Saudi as well as Sudanese support could have pushed him to sign the Saudi-mediated pact with Bashir". Colin Thomas-Jensen, an expert on Chad and Darfur at the International Crisis Group think-tank expressed doubts as to whether "this new deal will lead to any genuine thaw in relations or improvement in the security situation". Chadian rebel Union of Forces for Democracy and Development (UFDD) which had fought a hit-and-run war against Deby's forces in eastern Chad since 2006, stated that the Saudi-backed peace deal would not stop its military campaign.[115]

Oxfam announced on 17 June that it would permanently pull out of Gereida, the largest refugee camp, holding more than 130,000. The agency cited inaction by local authorities from the Sudan Liberation Movement (SLM), which controls the region, in addressing security concerns and violence against aid workers. An employee of the NGO Action by Churches Together was murdered in June in West Darfur. Vehicle hijackings also made them consider leaving.[116]

BBC News reported that a huge underground lake had been found. This find could eliminate the competition for water resources.[117]

France and Britain announced they would push for a UN resolution to dispatch African Union and United Nations peacekeepers to Darfur and would push for an immediate cease-fire in Darfur and are prepared to provide "substantial" economic aid "as soon as a cease-fire makes it possible."[118]

A 14 July 2007 article noted that in the past two months up to 75,000 Arabs from Chad and Niger had crossed into Darfur. Most have been relocated by Sudanese government to former villages of displaced non-Arab people.[119]

A hybrid UN/AU force was finally approved on 31 July with the unanimously approved United Nations Security Council Resolution 1769. UNAMID was to take over from AMIS by 31 December at the latest, and had an initial mandate up to 31 July 2008.[120]

On 31 July, Mahria gunmen surrounded mourners at the funeral of an important Terjem sheik and killed 60 with rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs) and belt-fed machine guns.[99]

From 3–5 August a conference was held in Arusha to unite the rebel groups to streamline the subsequent peace negotiations with the government. Most senior rebel leaders attended, with the notable exception of Abdul Wahid al Nur, who headed a rather small splinter group of the SLA/M that he had initially founded in 2003,[121] was considered to be the representatives of a large part of the displaced Fur people. His absence was damaging to the peace talks.[122] International officials stated that there is "no John Garang in Darfur", referring to the leader of the negotiating team of South Sudan, who was universally accepted by the various South Sudanese rebel groups.[123]

The participants were Gamali Galaleiddine,[124] Khalil Abdalla Adam, Salah Abu Surra, Khamis Abdallah Abakar, Ahmed Abdelshafi, Abdalla Yahya, Khalil Ibrahim (of the Justice and Equality Movement) and Ahmed Ibrahim Ali Diraige. Closed-door meetings between the AU-UN and rebel leaders, as well as among rebel leaders took place.[125] Eight more participants arrived on 4 August (including Jar el-Neby, Salah Adam Isaac and Suleiman Marajan[126]), while the SLM Unity faction boycotted the talks because the Sudanese government had threatened to arrest Suleiman Jamous if he left the hospital.[127] The rebel leaders aimed to unify their positions and demands, which included compensation for the victims and autonomy for Darfur.[124] They eventually reached agreement on joint demands, including power and wealth sharing, security, land and humanitarian issues.[128]

In the months through August, Arab tribes that had worked together in the Janjaweed militia began falling out among themselves, and further splintered. Thousands of Terjem and Mahria gunmen traveled hundreds of miles to fight in the strategic Bulbul river valley. Farther south, Habanniya and Salamat tribes clashed. The fighting did not result in as much killing as in 2003 and 2004. United Nations officials said the groups might be trying to seize land before peacekeepers arrived.[99]

On 18 September, JEM stated that if the peace talks with Khartoum should fail, they would step up their demands from self-determination to independence.[129]

On 30 September, the rebels overran an AMIS base, killing at least 12 peacekeepers in "the heaviest loss of life and biggest attack on the African Mission" during a raid at the end of Ramadan season.[130]

Peace talks started on 27 October in Sirte, Libya. The following groups attended:[131]

- Justice and Equality Movement splinters:

- Justice and Equality Movement–Collective Leadership, led by Bahr Idriss Abu Garda

- Justice and Equality Movement–Azraq, led by Idriss Ibrahim Azraq

- National Movement for Reform and Development, led by Khalil Abdullah

- Revolutionary Democratic Forces Front, led by Salah Abu Surrah

- United Revolutionary Force Front, led by Alhadi Agabeldour

- Sudan Liberation Movement–G19, led by Khamees Abdullah

- Sudan Federal Democratic Alliance, led by Ahmed Ibrahim Diraige

The following groups did not attend:

- Justice and Equality Movement, led by Khalil Ibrahim; they object to the presence of rebel groups they say had no constituency and no place at the table.

- Sudan Liberation Movement (Abdel Wahed), led by Abdel Wahed Mohamed el-Nur; the group has few forces, but its leader is highly respected; refused to attend until a force was deployed to stem the Darfur violence.

- Sudan Liberation Movement–Unity, originally led by Abdallah Yehya, includes many other prominent figures (Sherif Harir, Abu Bakr Kadu, Ahmed Kubur); the group with the largest number of rebel fighters; object for the same reason as JEM.

- Ahmed Abdel Shafi, a notable rebel enjoying strong support from the Fur tribe.

Faced with a boycott from the most important rebel factions, the talks were rebranded as an "advanced consultation phase", with official talks likely to start in November or December.[132]

On 15 November, nine rebel groups – six SLM factions, the Democratic Popular Front, the Sudanese Revolutionary Front and the Justice and Equality Movement–Field Revolutionary Command – signed a Charter of Unification and agreed to operate under the name of SLM/A henceforth.[133] On 30 November it was announced that Darfur's rebel movements had united into two large groups and were now ready to negotiate in an orderly manner with the government.[134]

2008

A fresh government/militia offensive trapped thousands of refugees along the Chadian border, the rebels and humanitarian workers said on 20 February.[135] As of 21 February, the total dead in Darfur stood at 450,000 with an estimated 3,245,000 people displaced.

On 10 May 2008 Sudanese government soldiers and Darfur rebels clashed in the city of Omdurman, opposite the capital of Khartoum, over the control of a military headquarters.[136] They also raided a police base from which they stole police vehicles. A Sudanese police spokesperson said that the leader of the assailants, Mohamed Saleh Garbo, and his intelligence chief, Mohamed Nur Al-Deen, were killed in the clash.

Witnesses said that heavy gunfire could be heard in the west of Sudan's capital. Sudanese troops backed by tanks, artillery, and helicopter gunships were immediately deployed to Omdurman, and fighting raged for several hours. After seizing the strategic military airbase at Wadi-Sayedna, the Sudanese soldiers eventually defeated the rebels. A JEM force headed to the Al-Ingaz bridge to cross the White Nile into Khartoum. By late afternoon, Sudanese TV claimed that the rebels had been "completely repulsed", while showing live images of burnt vehicles and corpses on the streets.[137]

The government imposed a curfew in Khartoum from 5 pm to 6 am, while aid agencies told their workers in the capital to stay indoors.

Some 93 soldiers and 13 policemen were killed along with 30 civilians in the attack on Khartoum and Omdurman. Sudanese forces confirmed that they found the bodies of 90 rebels and had spotted dozens more strewn outside the city limits. While Sudanese authorities claimed that up to 400 rebels could have been killed, the rebels stated that they lost 45 fighters dead or wounded. Sudanese authorities also claimed to have destroyed 40 rebel vehicles and captured 17.

2009

General Martin Agwai, head of the joint African Union-United Nations mission in Darfur, said the war was over in the region, although low-level disputes remained. There was still "Banditry, localised issues, people trying to resolve issues over water and land at a local level. But real war as such, I think we are over that," he said.[138]

2010 to 2012

In December 2010, representatives of the Liberation and Justice Movement, an umbrella organisation of ten rebel groups formed in February 2010,[139] started a fresh round of talks with the Sudanese Government in Doha. A new rebel group, the Sudanese Alliance Resistance Forces in Darfur was formed and JEM planned further talks.[140] Talks ended on 19 December with agreement only on basic principles; these included a regional authority and a referendum on autonomy. The possibility of a Darfuri Vice-President was discussed.[141][142]

In January 2011, the leader of the Liberation and Justice Movement, Dr. Tijani Sese, stated that the movement had accepted the core proposals of the Darfur peace document as proposed by the mediators in Doha. The proposals included a $300,000,000 compensation package for victims of atrocities in Darfur and special courts to conduct trials of persons accused of human rights violations. Proposals for a new Darfur Regional Authority were included. This authority would have an executive council of 18 ministers and would remain in place for five years. The current three Darfur states and state governments would continue to exist during this period.[143][144] In February, the Sudanese Government rejected the idea of a single region headed by a vice-president from the region.[145]

On 29 January, the LJM and JEM leaders issued a joint statement affirming their commitment to the Doha negotiations and intention to attend the Doha forum on 5 February. The Sudanese government postponed decision to attend the forum due to beliefs that an internal peace process without the involvement of rebel groups might be possible.[146] Later in February, the Sudanese Government agreed to return to Doha with a view to complete a new peace agreement by the end of that month.[147] On 25 February, both LJM and JEM announced that they had rejected the peace document proposed by the mediators in Doha. The main sticking points were the issues of a Darfuri vice-president and compensation for victims. The Sudanese government did not comment on the peace document.[148]

On 9 March, it was announced that two more states would be established in Darfur: Central Darfur around Zalingei and Eastern Darfur around Ed Daein. The rebel groups protested and stated that this was a bid to further divide Darfur's influence.[149]

Advising both the LJM and JEM during the Doha peace negotiations was the Public International Law & Policy Group (PILPG). Led by Dr. Paul Williams and Matthew T. Simpson, PILPG's team provided legal support.

In June, a new Darfur Peace Agreement (2011) was proposed by the Doha mediators. This agreement was to supersede the Abuja Agreement of 2005 and when signed, would halt preparations for a Darfur status referendum.[150] The proposed document included provisions for a Darfuri Vice-President and an administrative structure that included three states and a strategic regional authority, the Darfur Regional Authority.[151] The agreement was signed by the Government of Sudan and the Liberation and Justice Movement on 14 July 2011.[152]

Little progress occurred after September 2012 and the situation slowly worsened and violence was escalating.[153] The population of displaced Sudanese in IDP camps also increased.[154]

2013

A donors conference in Doha pledged US$3.6 billion to help rebuild Darfur. The conference was criticised in the region that the Sudan Liberation Army (Minni Minnawi) rebels had taken. According to the group's Hussein Minnawi, Ashma village and another town were close to the South Darfur capital of Nyala.[155]

On 27 April, following weeks of fighting, a coalition that included SLA and JEM said that they had taken Um Rawaba in North Kordofan, outside Darfur, and that they were headed for Khartoum to topple the president. The head of an SLA faction, Abdel Wahid Mohammed al-Nur, called it "a significant shift in the war".[156] An estimated 300,000 were displaced by violence from January through May.[157]

In North Darfur, the Rezeigat tribe and the Beni Hussein group signed a peace deal during July after an eruption of violence between the two groups killed hundreds. Later in July, the Misseriya and Salamat Arab tribes announced a ceasefire after battles killed over 200 people. The UN security counsel also announced a review of its UNAMID mission.[157]

During the first week of August, the Maalia claimed the Rezeigat had killed five members of their tribe in the southeastern region of Adila. They responded by seizing 400 Rizeigat cattle on 6 August. Community leaders intervened to prevent escalation. When the Maalia failed to return the cattle, violence broke out on 10 August.[158] The Rezeigat attacked and reportedly destroyed a Maaliya compound.[157] In the battle, 77 Maaliya and 36 Rezeigat were killed, and another 200 people were injured.[158] Both sides said Land Cruiser vehicles were used in the battle. The Maaliya accused the Rezeigat of attacking and burning villages while employing "heavy weaponry". On 11 August, the fighting spread to several other areas in southeastern Darfur. The violence reportedly arose over a land dispute.[157]

2014

On 19 March, peacekeepers said they had received recent reports of villages that were attacked and burned after the UN expressed concern over the increasing number of internally displaced persons. UNAMID said that the attacks were in Hashaba, about 100 kilometers north-west of the city Al-Fashir, the state capital of North Darfur.[159]

In November, local media reported that 200 women and girls had been raped by Sudanese soldiers in Tabit. Sudan denied it and did not permit the UN (who said their first inquiry was inconclusive "in part due to the heavy presence of military and police") to make another inquiry.[160] An investigation by Human Rights Watch (HRW) released in February said 221 were raped by government soldiers in "a mass rape that could constitute crimes against humanity". Witnesses reported three separate operations were carried out in one and a half days. Property was looted, men arrested, residents beaten and women and girls raped. Most of the town's population are Fur people. It had been controlled by rebel forces previously but HRW found no evidence that the rebel fighters were in or close to the village when it was attacked.[161]

3,300 villages were destroyed in 2014 in attacks on civilians according to the UN Panel of Experts. Government forces or those aligned with them were behind most attacks. There were more than 400,000 attacks during the first ten months of the year. The report said that it was "highly probable that civilian communities were targeted as a result of their actual or perceived affiliations with armed opposition groups" and that "such attacks were carried out with impunity".[162]

2015

2016

In September 2016, the Sudanese government reportedly launched chemical weapon attacks on civilian populations in Darfur, killing at least 250 people; the majority of the victims were children. It is believed that the munitions contained mustard gas or other blister agents.[163]

2017

2018

Reports from UNAMID and the African Center for Justice and Peace Studies suggest that low-level violence continued in Darfur through early 2018, with Sudanese government forces attacking communities in the Jebel Marra area.[164] As UNAMID forces began to be drawn down with an eye to exiting Darfur, there were competing views on the levels of unrest in the region: UN officials pointed to a significant reduction in the scale and distribution of violence in Darfur,[165] while other NGOS such as HRW highlighted persistent pockets of unrest. In 2018, Darfur was bombed and peace was signed. See 2019.

2019

The August 2019 Draft Constitutional Declaration, signed by military and civilian representatives during the 2018–19 Sudanese Revolution, requires that a peace agreement be made in Darfur and other regions of armed conflict in Sudan within the first six months of the 39-month transition period to democratic civilian government.[36][37]

In December 2019, The Guardian reported that irrigation projects built around community-based weirs are enabling "green shoots of peace" to appear, helping to end this conflict. This project was conducted with funding from the European Union and was overseen by the United Nations Environmental Program.[166]

2020

Militia leader Ali Kushayb, is arrested and charged with 50 crimes against humanity and war crimes in the Central African Republic.[167]

Mass shootings occurred in Darfur in July 2020.

Janjaweed participation

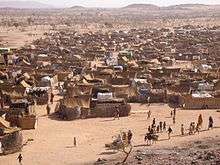

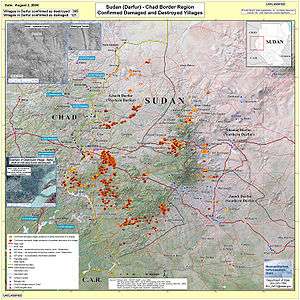

The well-armed Janjaweed quickly gained an advantage over rebel factions. By the spring of 2004, several thousand people – mostly from the non-Arab population – had been killed and as many as a million more had been driven from their homes, causing a major humanitarian crisis. The crisis took on an international dimension when over 100,000 refugees poured into neighboring Chad, pursued by militiamen who clashed with Chadian government forces along the border. More than 70 militiamen and 10 Chadian soldiers were killed in one gun battle in April. A United Nations observer team reported that non-Arab villages were singled out, while Arab villages were left untouched:

The 23 Fur villages in the Shattaya Administrative Unit have been completely depopulated, looted and burnt to the ground (the team observed several such sites driving through the area for two days). Meanwhile, dotted alongside these charred locations are unharmed, populated and functioning Arab settlements. In some locations, the distance between a destroyed Fur village and an Arab village is less than 500 meters.[168]

A 2011 study examined 1,000 interviews with black African participants who fled from 22 village clusters to various refugee camps in 2003 and 2004. The study found: 1) the frequency of hearing racial epithets during an attack was 70% higher when it was led by the Janjaweed alone compared to official police forces; it was 80% higher when the Janjaweed and the Sudanese Government attacked together; 2) the risk of displacement was nearly 110% higher during a joint attack compared to when the police or Janjaweed acted alone, and 85% higher when Janjaweed forces attacked alone compared to when the attack was only perpetrated by government forces; 3) attacks on food and water supplies made it 129% more likely for inhabitants to be displaced compared to attacks that involved house burnings or killings; 4) perpetrators knew and took "special advantage" of the susceptibility of Darfur residents to attacks focused on basic resources. This vulnerability came against the backdrop of increased regional desertification.[169]

Rape of women and young girls

Immediately after the Janjaweed entered the conflict, the rape of women and young girls, often by multiple militiamen and often throughout entire nights, began to be reported at a staggering rate.[170] Children as young as 2 years old were reported victims, while mothers were assaulted in front of their children.[171] Young women were attacked so violently that they were unable to walk following the attack.[172]

Non-Arab people were reportedly raped by Janjaweed militiamen as a result of the Sudanese government's goal of completely eliminating the presence of black Africans and non-Arabs from Darfur.[173] The Washington Post Foreign Service interviewed verified victims of the rapes and recorded that Arabic terms such as "abid" and "zurga" were used, which mean slave and black. One victim, Sawelah Suliman, was told by her assailant, "Black girl, you are too dark. You are like a dog. We want to make a light baby."[174] In an 88-page report, victims from Darfur have also accused the Rapid Support Forces of rape and assault as recently as 2015.[175]

Mortality figures

Multiple casualty estimates have been published since the war began, ranging from roughly 10,000 civilians (Sudan government) to hundreds of thousands.[176]

In September 2004, 18 months after the conflict began, the World Health Organization estimated that there had been 50,000 deaths in Darfur, mostly due to starvation. An updated estimate published the following month put the number of deaths for the 6-month period from March to October 2004 due to starvation and disease at 70,000; These figures were criticized because they only considered short periods and did not include deaths from violence.[177] A more recent British Parliamentary Report estimated that over 300,000 people had died [178] and others have published even higher death toll estimates.

In March 2005, the UN's Emergency Relief Coordinator Jan Egeland estimated that 10,000 people were dying each month, excluding deaths due to ethnic violence.[179] An estimated 2.7 million people had at that time been displaced from their homes, mostly seeking refuge in camps in Darfur's major towns.[180] Two hundred thousand had fled to neighboring Chad. Reports of violent deaths compiled by the UN indicate between 6,000 and 7,000 fatalities from 2004 to 2007.[181]

In May 2005, the Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED) of the School of Public Health of the Université catholique de Louvain in Brussels, Belgium published an analysis of mortality in Darfur. Their estimate stated that from September 2003 to January 2005, between 98,000 and 181,000 persons died in Darfur, including 63,000 to 146,000 excess deaths.[182]

In August 2010, Dr. Eric Reeves argued that total mortality from all violent causes, direct and indirect, at that point in the conflict, exceeded 500,000. His analysis took account of all previous mortality data and studies, including that by the Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disaster.[183][184]

The UN disclosed on 22 April 2008 that it might have underestimated the Darfur death toll by nearly 50%.[185]

In July 2009, The Christian Science Monitor published an op-ed stating that many of the published mortality rates have been misleading because they include a large number of people who had died of disease and malnutrition, as well as those who died from direct violence.[186]

In January 2010, the Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters published an article in a special issue of The Lancet. The article, entitled "Patterns of mortality rates in Darfur conflict", estimated with 95% confidence that the excess number of deaths is between 178,258 and 461,520 (with a mean of 298,271), with 80% of these due to disease.[187]

International response

International attention to the Darfur genocide largely began with reports by Amnesty International in July 2003 and the International Crisis Group in December 2003. However, widespread media coverage did not start until the outgoing United Nations Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator for Sudan, Mukesh Kapila, called Darfur the "world's greatest humanitarian crisis" in March 2004.[188] Organizations such as STAND: A Student Anti-Genocide Coalition, later under the umbrella of Genocide Intervention Network, and the Save Darfur Coalition emerged and became particularly active in the areas of engaging the United States Congress and President on the issue and pushing for divestment, initially launched by Adam Sterling under the auspices of the Sudan Divestment Task Force.

In May 2009 the Mandate Darfur was canceled because the "Sudanese government is obstructing the safe passage of Darfurian delegates from Sudan."[189] The Mandate was a conference that would have brought together 300 representatives from different regions of Darfur's civil society.[189] The conference planned was to be held in Addis Ababa sometime in early May.

International Criminal Court

In March 2005, the UN Security Council formally referred the situation in Darfur to the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, taking into account the report of the International Commission of Inquiry on Darfur, authorized by United Nations Security Council Resolution 1564 of 2004, but without mentioning specific crimes.[190] Two permanent members of the Security Council, the United States and China, abstained from the vote on the referral resolution.[191]

In April 2007, the Judges of the International Criminal Court issued arrest warrants against the former Minister of State for the Interior, Ahmed Haroun, and a Janjaweed leader, Ali Kushayb, for crimes against humanity and war crimes.[192] The Sudan Government said that the ICC had no jurisdiction to try Sudanese citizens and that it would not surrender the two men.[193]

On 14 July 2008, the Prosecutor filed ten charges of war crimes against Sudan's incumbent President Omar al-Bashir, including three counts of genocide, five of crimes against humanity and two of murder. The Prosecutor claimed that Mr. al-Bashir "masterminded and implemented a plan to destroy in substantial part" three tribal groups in Darfur because of their ethnicity. Leaders from three Darfur tribes sued ICC prosecutor Luis Moreno Ocampo for libel, defamation, and igniting hatred and tribalism.[194]

After an arrest warrant was issued for the Sudanese president in March 2009, the Prosecutor appealed to add genocide charges. However, the Pre-Trial Chamber found that there was no reasonable ground to support the contention that he had a specific intent to commit genocide (dolus specialis), which is an intention to destroy, in whole or in part, a protected group. The definition adopted by the Pre-Trial Chamber is the definition of the Genocide Convention, the Rome Statute, and some ICTY cases. On 3 February 2010 the Appeals Chamber of the ICC found that the Pre-Trial Chamber had applied "an erroneous standard of proof when evaluating the evidence submitted by the Prosecutor" and that the Prosecutor's application for a warrant of arrest on the genocide charges should be sent back to the Pre-Trial Chamber to review based on the correct legal standard.[195] In July 2010, al-Bashir was charged with three counts of genocide in Darfur by the International Criminal Court for orchestrating the Darfur genocide.[196]

Al-Bashir was the first incumbent head of state charged with crimes under the Rome Statute.[197] He rejected the charges and said, "Whoever has visited Darfur, met officials and discovered their ethnicities and tribes ... will know that all of these things are lies."[198]

It is expected that al-Bashir will not face trial in The Hague until he is apprehended in a nation which accepts ICC jurisdiction, as Sudan is not a party to the Rome Statute, which it signed but did not ratify.[199] Payam Akhavan, a professor of international law at McGill University in Montreal and a former war crimes prosecutor, says although he may not go to trial, "He will effectively be in prison within the Sudan itself...Al-Bashir now is not going to be able to leave the Sudan without facing arrest."[200] The Prosecutor warned that authorities could arrest the President if he enters international airspace. The Sudanese government has announced that the Presidential plane would be accompanied by jet fighters.[201] However, the Arab League announced solidarity with al-Bashir. Since the warrant, he has visited Qatar and Egypt. The African Union also condemned the charges.

Some analysts think that the ICC indictment is counterproductive and harms the peace process. Only days after the ICC indictment, al-Bashir expelled 13 international aid organizations from Darfur and disbanded three domestic aid organizations.[202] In the aftermath of the expulsions, conditions in the displaced camps deteriorated.[203] Previous ICC indictments, such as the arrest warrants of the LRA leadership in the ongoing war in northern Uganda, were also accused of harming peace processes by criminalizing one side of a war.[204]

Foreign support for the Sudanese government

Al-Bashir sought the assistance of non-western countries after the West, led by America, imposed sanctions against him. He said, "From the first day, our policy was clear: To look eastward, toward China, Malaysia, India, Pakistan, Indonesia, and even Korea and Japan, even if the Western influence upon some [of these] countries is strong. We believe that the Chinese expansion was natural because it filled the space left by Western governments, the United States, and international funding agencies. The success of the Sudanese experiment in dealing with China without political conditions or pressures encouraged other African countries to look toward China."[205]

In 2007, Amnesty International issued a report[206][207][208] accusing China and Russia of supplying arms, ammunition and related equipment to Sudan, some of which the government may have transferred to Darfur in violation of a UN arms embargo. The report claims that Sudan imported 10–20 combat aircraft from China in the early-mid-2000s, including three A-5 Fantan fighters that have been sighted in Darfur.[209] The report provides evidence that the Sudan Air Force conducted indiscriminate aerial bombings of villages in Darfur and eastern Chad using ground attack fighters and repurposed Antonov transport planes. However, it does not specify whether the ground attack fighters in question are those purchased from China in the early-mid-2000s, and the Antonovs' origin remains unclear. The report also lists seven Soviet- or Russian-made Mi-24 Hind gunships that had been deployed to Darfur, though without specifying which country sold them to Sudan, or when.[210] While noting that Russia sold arms worth tens of millions of dollars to Sudan in 2005 alone,[211] the report does not specifically identify any weapons sold to Sudan by Russia after the outbreak of the Darfur conflict or after the imposition of the UNSC ban on arms transfers to Darfur, and it does not provide any evidence that any such weapons were deployed to Darfur.

The NGO Human Rights First claimed that over 90% of the light weapons currently being imported by Sudan and used in the conflict are from China.[212] Human rights advocates and opponents of the Sudanese government portray China's role in providing weapons and aircraft as a cynical attempt to obtain oil, just as colonial powers once supplied African chieftains with the military means to maintain control as they extracted natural resources.[213][214] According to China's critics, China threatened to use its veto on the U.N. Security Council to protect Khartoum from sanctions and was able to water down every resolution on Darfur in order to protect its interests.[215] Accusations of the supply of weapons from China, which were then transferred to Darfur by the Sudanese government in violation of the UN arms embargo, continued in 2010.[216]

Sarah Wykes, a senior campaigner at Global Witness, an NGO that campaigns for better natural resource governance, says: "Sudan has purchased about $100m in arms from China and has used these weapons against civilians in Darfur."[214]

According to the report Following the Thread: Arms and Ammunition Tracing in Sudan and South Sudan, released in May 2014 by the Swiss research group Small Arms Survey, "Over the period 2001–12, Khartoum's reports to UN Comtrade reveal significant fluctuation in annual conventional arms imports. The majority of the Sudanese government's total self-reported imports of small arms and light weapons, their ammunition, and ‘conventional weapons’ over the period originated in China (58 per cent), followed by Iran (13 per cent), St. Vincent and the Grenadines (9 per cent), and Ukraine (8 per cent)."[217] The report found that Chinese weapons were pervasive among most parties to the Sudanese conflicts, including the war in Darfur, but identified few if any weapons of Russian origin. (The section "Chinese weapons and ammunition" receives 20 pages in the report, whereas the only mention of Russian arms is to be found in the sentence "the majority of...mines [in South Sudan] have been of Chinese and Soviet/Russian origin.").

China and Russia denied they had broken UN sanctions. China has a close relationship with Sudan and increased its military co-operation with the government in early 2007. Because of Sudan's plentiful supply of oil, China considers good relations with Sudan to be a strategic necessity.[218][219][220] China has direct commercial interests in Sudan's oil. China's state-owned company CNPC controls between 60 and 70 percent of Sudan's total oil production. Additionally, it owns the largest single share (40 percent) of Sudan's national oil company, Greater Nile Petroleum Operating Company.[221] China consistently opposed economic and non-military sanctions on Sudan.[222]

In March 2007, threats of boycotting the Olympic games came from French presidential candidate François Bayrou, in an effort to stop China's support.[223][224] Sudan divestment efforts concentrated on PetroChina, the national petroleum company with extensive investments in Sudan.[225]

Criticism of international response

Gérard Prunier, a scholar specializing in African conflicts, argued that the world's most powerful countries have limited themselves to expressing concern and demand for the United Nations to take action. The UN, lacking funding and military support of the wealthy countries, initially left the African Union to deploy a token force without a mandate to protect civilians.[188]

On 16 October 2006, Minority Rights Group (MRG) published a critical report, challenging that the UN and the great powers could have prevented the crisis and that few lessons appeared to have been drawn from the Rwandan genocide. MRG's executive director, Mark Lattimer, stated that: "this level of crisis, the killings, rape and displacement could have been foreseen and avoided ... Darfur would just not be in this situation had the UN systems got its act together after Rwanda: their action was too little too late."[226] On 20 October 120 genocide survivors of The Holocaust, and the Cambodian and Rwandan Genocides, backed by six aid agencies, submitted an open letter to the European Union, calling on them to do more, proposing a UN peacekeeping force as "the only viable option."[227]

In the media

Watchers of the Sky, a 2014 documentary by Edet Belzberg, interviews former journalist and United States Ambassador to the United Nations Samantha Power about the war in Darfur. Also featured is Luis Moreno Ocampo, former ICC jurist and lead prosecutor on the ICC investigation in Darfur.[228][229] Brutality of militias, violence used by armed forces, corruption and human right abuse were also shown in ER television series (e.g. episodes 12x19, 12x20), and in The Devil Came on Horseback,[230] a documentary made in 2007.

See also

- Banu Hilal

- Bibliography of the Darfur conflict

- Boswells School

- Breidjing Camp

- Chadian Civil War (2005–10)

- Command responsibility

- Darfur genocide

- Genocides in history

- List of civil wars

- List of famines

- List of wars 2003–present

- List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll

- Lost Boys of Sudan

- Second Sudanese Civil War

- Slavery in Sudan

- Team Darfur

Notes

- The name "Land Cruiser War" for the conflict in Darfur is primarily used by Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) rebels due to the widespread use of Toyota Land Cruisers as technicals on both sides of the war.[26]

a Known as the National Redemption Front prior to 2011.

b Signed the Doha Darfur Peace Agreement in 2011.[24]

c Number does not represent the number of soldiers stationed in Darfur, but the total number of military personnel.[19][25]

References

- "Three Darfur factions establish new rebel group". Sudan Tribune. 7 July 2017.

- "Al Bashir threatens to 'disarm Darfur rebels' in South Sudan". Radio Dabanga. 29 April 2015. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- Afrol News – Eritrea, Chad accused of aiding Sudan rebels Archived 29 June 2012 at Archive.today 7 de septiembre de 2007

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 5 August 2012. Retrieved 2015-11-24.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Sudan adjusting to post-Gaddafi era

- "Uganda Signals Diplomatic Breakthrough With Sudan on Rebels". 13 February 2015. Archived from the original on 22 January 2018. Retrieved 22 January 2018 – via www.Bloomberg.com.

- Тоp-10 обвинений Беларуси в сомнительных оружейных сделках

- Торговля оружием и будущее Белоруссии

- Завоюет ли Беларусь позиции на глобальных рынках оружия?

- Andrew McGregor (31 May 2019). "Continued Detention of Rebel POWs suggests Sudan's military rulers are not ready to settle with the Armed Opposition". Aberfoyle Inzernational Security. Archived from the original on 24 June 2019. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- "Sudan's Bashir Forced to Step Down". Reuters. 11 April 2019. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- "Sudan: Application for summonses for two war crimes suspects a small but significant step towards justice in Darfur | Amnesty International". Amnesty.org. 27 February 2007. Archived from the original on 9 August 2009. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- "Sudanese authorities arrest members of Bashir's party: Source". Reuters. 20 April 2019.

- : Le Secrétaire général et la Présidente de la Commission de l’Union africaine nomment M. Martin Ihoeghian Uhomoibhi, du Nigéria, Représentant spécial conjoint pour le Darfour et Chef de la MINUAD Archived 12 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, UN, 27 October 2015

- : Le Secrétaire général et l’Union africaine nomment le général de corps d’armée Frank Mushyo Kamanzi, du Rwanda, Commandant de la force de la MINUAD Archived 12 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, UN, 14 December 2015

- "Sudan, two rebel factions discuss ways to hold peace talks on Darfur conflict". Sudan Tribune. 5 June 2016. Archived from the original on 6 June 2016. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- "Three Darfur factions establish new rebel group". Sudan Tribune. 7 July 2017. Archived from the original on 9 July 2017. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- "Series of explosions at weapons cache rock town in West Kordofan". Sudan Tribune. 6 June 2016. Archived from the original on 6 June 2016. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- "Who are Sudan's Jem rebels?". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 18 March 2015. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- Military Balance 2007, 293.

- : Faits et chiffres Archived 30 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine, UN, 26 October 2016

- : (5a) Fatalities by Year, Mission and Incident Type up to 31 Aug 2016 Archived 13 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine, UN, 8 September 2016

- "Darfur Conflict". Thomson Reuters Foundation. Archived from the original on 24 May 2015. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- "Sudan". United to End Genocide. Archived from the original on 13 July 2015. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- "Darfur Peace Agreement – Doha draft" (PDF). Sudan Tribune. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- "Sudan Military Strength". GFP. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- Neville (2018), p. 20.

- "Q&A: Sudan's Darfur conflict". BBC News. 8 February 2010. Archived from the original on 14 April 2009. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- "Reuters AlertNet – Darfur conflict". Alertnet.org. Archived from the original on 1 May 2010. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- "The Prosecutor v. Omar Hassan Ahmad Al Bashir". International Criminal Court. Archived from the original on 8 May 2016. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- de Waal, Alex (25 July 2004). "Darfur's Deep Grievances Defy All Hopes for An Easy Solution". The Observer. London. Archived from the original on 28 August 2013. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- "Rights Group Says Sudan's Government Aided Militias". Washington Post. 20 July 2004. Archived from the original on 4 January 2006. Retrieved 14 January 2007.

"Darfur – Meet the Janjaweed". American Broadcasting Company. 3 June 2008. Archived from the original on 12 October 2008. Retrieved 16 July 2008. - Uppsala Conflict Data Program Conflict Encyclopedia, Sudan, one-sided conflict, Janjaweed – civilians Archived 22 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Adam Jones (27 September 2006). Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction. Routledge. p. 373. ISBN 978-1-134-25980-9. Archived from the original on 19 March 2015. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- "Will peace return to Darfur?". BBC News. 23 February 2010. Archived from the original on 8 July 2010. Retrieved 11 July 2010.

- "Jem Darfur rebels snub Sudan peace talks over 'attacks'". BBC News. 4 May 2010. Archived from the original on 8 July 2010. Retrieved 11 July 2010.

- FFC; TMC (4 August 2019). "(الدستوري Declaration (العربية))" [(Constitutional Declaration)] (PDF). raisethevoices.org (in Arabic). Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- FFC; TMC; IDEA; Reeves, Eric (10 August 2019). "Sudan: Draft Constitutional Charter for the 2019 Transitional Period". sudanreeves.org. Archived from the original on 10 August 2019. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- Straus, Scott (January–February 2005). "Darfur and the Genocide Debate". Foreign Affairs. 84 (1): 123–133. doi:10.2307/20034212. JSTOR 20034212. Archived from the original on 24 March 2014. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- Richard Wachman (8 December 2007). "Water becomes the new oil as world runs dry". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- Straus, Scott (January–February 2005). "Darfur and the Genocide Debate". Foreign Affairs. 84 (1): 123–133. doi:10.2307/20034212. JSTOR 20034212.

- Johnson, Hilde F. (2011). Waging Peace in Sudan: The Inside Story of the Negotiations that Ended Africa's Longest Civil War. Sussex Academic Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-84519-453-6. Archived from the original on 29 June 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- Vukoni Lupa Lasaga, "The slow, violent death of apartheid in Sudan," 19 September 2006, Norwegian Council for Africa.

- George Ayittey, Africa and China, The Economist, 19 February 2010

- "How the Multilateral Institutions Compounded Africa's Economic Crisis", George B.N. Ayittey; Law and Policy in International Business, Vol. 30, 1999.

- Koigi wa Wamwere (2003). Negative Ethnicity: From Bias to Genocide. Seven Stories Press. p. 152. ISBN 978-1-58322-576-9. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

George B.N. Ayittey (15 January 1999). Africa in Chaos: A Comparative History. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-312-21787-7. Archived from the original on 5 May 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

George B. N. Ayittey (2006). Indigenous African Institutions. Transnational Publishers. ISBN 978-1-57105-337-4. Archived from the original on 2 September 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

Diallo, Garba (1993). "Mauritania, the other apartheid?". Current African Issues. Nordiska Afrikainstitutet (16). Archived from the original on 24 March 2014. Retrieved 23 March 2014. - Alan Dershowitz (3 November 2008). The Case Against Israel's Enemies: Exposing Jimmy Carter and Others Who Stand in the Way of Peace. John Wiley & Sons. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-470-44745-1. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- Bauch, Hubert (6 March 2009). "Ex-minister speaks out against Sudan's al-Bashir". Montreal Gazette. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- Flint & de Waal 2005, p. 76-77.

- "Report of the International Commission of Inquiry on Darfur to the United Nations Secretary-General (PDF)" (PDF). United Nations. 25 January 2005. p. 129. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 September 2013. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- Flint & de Waal 2005, p. 99.

- Flint & de Waal 2005, p. 99–100.

- Flint & de Waal 2005, pp. 60, 101–103.

- 'Dozens killed' in Sudan attack Archived 1 December 2005 at the Wayback Machine (BBC) 24 May 2004

- Sudan ex-rebel joins government Archived 14 July 2005 at the Wayback Machine (BBC) 10 July 2005

- Sudan VP Garang killed in crash Archived 29 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine (BBC) 1 August 2005

- Chad fightback 'kills 300 rebels' Archived 1 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine (BBC) 20 December 2005

- Chad in 'state of war' with Sudan Archived 1 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine By Stephanie Hancock, BBC News, N'Djamena, 23 December 2005

- "Darfur Peace Agreement" (PDF). Uppsala Conflict Data Program. 5 May 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2013.

- Kessler, Glenn & Emily Wax (5 May 2006). "Sudan, Main Rebel Group Sign Peace Deal". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- "Main parties sign Darfur accord". BBC News. 5 May 2006. Archived from the original on 12 May 2011.

- "Annan outlines Darfur peace plans" Archived 27 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, BBC, 2 August 2006

- Ryu, Alisha (9 August 2006). "Disagreements Over Darfur Peace Plan Spark Conflict". Voice of America. Archived from the original on 15 August 2006.

- "In a Darfur town, women recount numbing tale of their hell of rape and suffering". cbs11tv.com. 27 May 2007.

Grave, A Mass (28 May 2007). "The horrors of Darfur's ground zero". The Australian. Archived from the original on 4 February 2009. Retrieved 29 May 2007.

"Darfur women describe gang-rape horror". Associated Press. 27 May 2007. Archived from the original on 2 June 2007. - "U.N. Official Warns of Major New Sudanese Offensive in Darfur" Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Washington Post, 18 August 2006

- "UN Envoy Says Sudan Rights Record in Darfur Poor" Archived 18 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine, Voice of America, 17 August 2006

- "Sudan reiterates opposition to replacing AU troop with UN forces in Darfur" Archived 15 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine, People's Daily, 19 August 2006

- "US threatens Sudan after UN resistance" Archived 19 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Independent Online, 19 August 2006

- "Khartoum turns down UN meeting on Darfur peace" Archived 4 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Deutsche Presse-Agentur, 24 August 2006

- "UN Security Council to meet on Darfur without Khartoum attendance" Archived 11 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Deutsche Presse-Agentur, 24 August 2006

- "Sudan: Sexual Violence Spikes Around South Darfur Camp" Archived 20 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Integrated Regional Information Networks, 24 August 2006

- "Sudan". Amnesty International. 14 March 2003. Archived from the original on 22 November 2018. Retrieved 8 November 2007.

- "US Warns of Security Crisis in Darfur Unless UN Force Deploys" Archived 25 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine, Voice of America, 25 August 2006

- "U.S. journalist returns home from Sudan prison", NBC News, 10 September 2006

- "U.S. journalist in Darfur court for espionage". Reuters. 26 August 2006. Archived from the original on 1 October 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2017 – via Sudantribune.com.

- United Nations Security Council Verbatim Report 5519. S/PV/5519 31 August 2006. Retrieved 21 August 2007.

- "Sudan Rejects UN Resolution on Darfur Peacekeeping" Archived 6 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine, Voice of America, 31 August 2006

- "Sudan reported to launch new offensive in Darfur", Associated Press, 1 September 2006

- "Defiant Sudan sets deadline for Darfur peacekeeper exit" Archived 3 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine, AFP, 5 September 2006

- " Chad's president says he supports U.N. force for neighboring Darfur" Archived 19 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Associated Press, 4 September 2006

- "Africa Union 'will quit Darfur'" Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, BBC, 5 September 2006

- "African Union's Darfur force may stay past Sept 30", Reuters, 6 September 2006

- "U.N. refugee chief warns of Darfur "catastrophe" Archived 31 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Reuters, 8 September 2006 Archived copy at WebCite (30 July 2007).

- "Sudan bombing civilians in Darfur – EU envoy" Archived 29 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine, Reuters, 12 September 2006

- "Violence in Darfur cuts off 355,000 people from food aid" Archived 19 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine, People's Daily, 12 September 2006

- "Annan calls for "urgent" Security Council action on Darfur", People's Daily, 12 September 2006

- "Ex-rebels says would accept UN in Darfur" Archived 29 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine, Reuters, 14 September 2006

- "We don't want Sudan to turn into "another Iraq" in the region – al-Bashir". Kuwait News Agency. 21 September 2006. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007.

- "Genocide survivors urges EU sanctions over Darfur" Archived 6 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Reuters, 20 October 2006

- "AU will not abandon Darfur – AU chairman" Archived 23 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Reuters, 2 October 2006

- "200 UN troops to deploy in Darfur", Toronto Sun, 10 October 2006

- "Extend Sudan U.N. mission" Archived 20 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine, United Press International, 9 October 2006

- "Forty countries face food shortages, Darfur crisis is the most pressing: UN agency" Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, United Nations, 9 October 2006

- "UN official: Khartoum knew of Darfur militia raid", The Guardian, 10 October 2006

- "Nigerian FM arrives in Khartoum for talks on Darfur" Archived 15 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine, People's Daily, 12 October 2006

- "Bush signs law setting sanctions on Darfur crimes", Washington Post, 13 October 2006

- "UN envoy is told to leave Sudan" Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News, 22 October 2006

- Pleming, Sue (1 November 2006). "U.S. works on international plan for Darfur". Reuters. Archived from the original on 11 January 2008.

- "Sudan says ready for talks with Darfur's NRF rebels" Archived 5 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Reuters, 9 November 2006 Archived copy at WebCite (30 July 2007).

- Gettleman, Jeffrey, "Chaos in Darfur on rise as Arabs fight with Arabs ", news article, The New York Times, 3 September 2007, pp 1, A7

- "US Rice hopes Sudan will okay Darfur force" Archived 3 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Sudan Tribune, 17 November 2006

- "Sudan "did not" give ok over international force for Darfur – top official". Kuwait News Agency. 17 November 2006. Archived from the original on 22 October 2007.

- "UN insists Khartoum will allow UN force into Darfur", Deutsche Presse-Agentur, 19 November 2006

- "Sudan 'begins new Darfur attacks'" Archived 6 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News, 18 November 2006

- "Army attack against Darfur civilians was unprovoked – UN" Archived 23 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Sudan Tribune, 25 November 2006

- "Sudan: The Passion of the Present". Archived from the original on 24 March 2014. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- "73 villagers killed, rebel group says". LA Times. 18 April 2007.

- "The UN and Darfur: Watching, but still waiting". The Economist. 16 March 2007. Archived from the original on 10 June 2008. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- "African troops killed in Darfur". BBC News. 2 April 2007. Archived from the original on 18 June 2011. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- Hoge, Warren (18 April 2007). "Sudan Flying Arms to Darfur, Panel Reports". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 May 2013. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- "Attacks in eastern Chad last month killed up to 400, U.N. refugee agency says". International Herald Tribune. 18 April 2007. Archived from the original on 14 February 2008.

- "Up to 3,000 villagers flee homes in south-east Chad following fresh attacks". UNHCR. 3 April 2007. Archived from the original on 23 November 2008. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- "Bush Presses Sudan on Darfur, Citing possible US sanctions". New York Times. 19 April 2007. Archived from the original on 15 May 2012. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- "Darfur war crimes suspect defiant". BBC News. 28 February 2007. Archived from the original on 28 May 2016. Retrieved 3 October 2016.

-

"Saudi Arabia Brokers Agreement Between Sudan and Chad on Darfur". PR Newswire. 3 May 2007. Archived from the original on 30 August 2007.