Kurdish–Turkish conflict (1978–present)

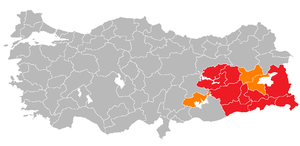

The Kurdish–Turkish conflict[note 1] is an armed conflict between the Republic of Turkey and various Kurdish insurgent groups,[91] which have demanded separation from Turkey to create an independent Kurdistan,[42][82] or to have autonomy[92][93] and greater political and cultural rights for Kurds inside the Republic of Turkey.[94] The main rebel group is the Kurdistan Workers' Party[95] or PKK (Kurdish: Partiya Karkerên Kurdistan). Although the Kurdish-Turkish conflict has spread to many regions,[96] most of the conflict has taken place in Northern Kurdistan, which corresponds with southeastern Turkey.[97] The PKK's presence in Iraqi Kurdistan has resulted in the Turkish Armed Forces carrying out frequent ground incursions and air and artillery strikes in the region,[98][99] and its influence in Western Kurdistan has led to similar activity there. The conflict has cost the economy of Turkey an estimated $300 to 450 billion, mostly military costs. It has also affected tourism in Turkey.[100][101][102]

A revolutionary group, the PKK was founded in 1978 in the village of Fis (near Lice) by a group of Kurdish students led by Abdullah Öcalan.[103] The initial reason given by the PKK for this was the oppression of Kurds in Turkey.[104][105] At the time, the use of Kurdish language, dress, folklore, and names were banned in Kurdish-inhabited areas.[106] In an attempt to deny their existence, the Turkish government categorized Kurds as "Mountain Turks" until 1991.[106][107][108][109] The words "Kurds", "Kurdistan", or "Kurdish" were officially banned by the Turkish government.[110][111] Following the military coup of 1980, the Kurdish language was officially prohibited in public and private life.[112] Many who spoke, published, or sang in Kurdish were arrested and imprisoned.[113] The PKK was formed as part of a growing discontent over the suppression of Turkey's Kurds, in an effort to establish linguistic, cultural, and political rights for Turkey's Kurdish minority.[114]

However, the full-scale insurgency did not begin until 15 August 1984, when the PKK announced a Kurdish uprising. Since the conflict began, more than 40,000 have died, the vast majority of whom were Kurdish civilians killed by the Turkish Armed Forces.[115] The European Court of Human Rights has condemned Turkey for thousands of human rights abuses.[116][117] Many judgments are related to the systematic executions of Kurdish civilians,[118] torture,[119] forced displacements,[120] destroyed villages,[121][122][123] arbitrary arrests,[124] and the disappearing or murder of Kurdish journalists, activists and politicians.[125][126][127]

In the first days of February 1999, the leader of PKK, Abdullah Öcalan was captured in Nairobi by the Turkish National Intelligence Agency (MIT)[128] and taken to Turkey, where he remains in prison.[129] The first insurgency lasted until 1 September 1999,[82][130] when the PKK declared a unilateral ceasefire. The armed conflict was later resumed on 1 June 2004, when the PKK declared an end to its ceasefire.[131][132] After the summer of 2011, the conflict became increasingly violent, with the resumption of large-scale hostilities.[102]

In 2013, the Turkish government started talks with Öcalan. Following mainly secret negotiations, a largely successful ceasefire was put in place by both the Turkish state and the PKK. On 21 March 2013, Öcalan announced the "end of armed struggle" and a ceasefire with peace talks.[4][133]

On 25 July 2015, the conflict resumed when the Turkish Air Force bombed PKK positions in Iraq,[134] in the midst of tensions arising from Turkish involvement in the Rojava–Islamist conflict in Syria. With the resumption of violence, hundreds of Kurdish civilians have been killed and numerous human rights violations have occurred, including torture, rape, and widespread destruction of property.[135][136] Turkish authorities have destroyed substantial parts of many Kurdish-majority cities including Diyarbakır, Şırnak, Mardin, Cizre, Nusaybin, and Yüksekova.[136][137]

Background

Kurdish rebellions against the Ottoman Empire go back two centuries, but the modern conflict dates back to the abolition of the Caliphate. During the reign of Abdul Hamid II, who was Caliph as well as Sultan, the Kurds were loyal subjects of the Caliph and the establishment of a secular republic following the abolition of the Caliphate in 1924 became a source of widespread resentment.[138] The establishment of the Turkish nationalist state and Turkish citizenship brought an end to the centuries-old millet system, which had unified the Muslim ethnic groups of the Ottoman Empire under a unified Muslim identity. The diverse Muslim ethnic groups of the former Empire were considered Turkish by the newly formed secular Turkish state, which did not recognize an independent Kurdish or Islamic national identity. One of the consequences of these seismic changes was a series of uprisings in Turkey's Kurdish-populated eastern and southeastern regions, including the brutally suppressed Sheikh Said rebellion in 1925.[139] Other major historical events include the Bitlis uprising (1914), Koçgiri Rebellion (1920), Beytussebab rebellion (1924), Ararat rebellion (1930), and the Dersim Rebellion (1938).

The Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) was founded in 1974 by Abdullah Öcalan. Initially a Marxist–Leninist organization, it abandoned orthodox communism and adopted a program of greater political rights and cultural autonomy for Kurds. Between 1978 and 1980, the PKK engaged in limited urban warfare with the Turkish state to these aims. The organization restructured itself and moved the organization structure to Syria between 1980 and 1984, just after the 1980 Turkish coup d'état.

The rural-based insurgency lasted between 1984 and 1992. The PKK shifted its activities to include urban warfare between 1993 and 1995 and between 1996 and 1999. The leader of the party was captured in Kenya in early 1999, with the support of CIA. After a unilaterally declared peace initiative in 1999, the PKK resumed the conflict due to a Turkish military offensive in 2004.[38] Since 1974 it had been able to evolve, adapt, and go through a metamorphosis,[140] which became the main factor in its survival. It had gradually grown from a handful of political students to a dynamic organization.

In the aftermath of the failed 1991 uprisings in Iraq against Saddam Hussein, the UN established no-fly zones over Kurdish areas of Iraq, giving those areas de facto independence.[141] The PKK was forced to retreat from Lebanon and Syria as a part of an agreement between Turkey and the United States. The PKK moved their training camps to the Qandil Mountains and as a result Turkey responded with Operation Steel (1995) and Operation Hammer (1997) in a failed attempt to crush the PKK.[142]

In 1992 Colonel Kemal Yilmaz declared that the Special Warfare Department (the seat of the Counter-Guerrilla) was still active in the conflict against the PKK.[143] The U.S. State Department echoed concerns of Counter-Guerrilla involvement in its 1994 Country Report on Human Rights Practices for Turkey. The Counter-Guerrilla units were involved in serious human rights violations.[144]

Öcalan was captured in Kenya on 15 February 1999, allegedly involving CIA agents with Greek Embassy cooperation, resulting in his transfer to the Turkish authorities. After a trial he was sentenced to death, but this sentence was commuted to lifelong aggravated imprisonment when the death penalty was abolished in Turkey in August 2002.

With the invasion of Iraq in 2003, much of the arms of the Iraqi Army fell into the hands of the Iraqi Kurdish Peshmerga militias.[145] The Peshmerga became the de facto army of Iraqi Kurdistan and Turkish sources claim many of its weapons found their way into the hands of other Kurdish groups such as the PKK and the PJAK (a PKK offshoot which operates in Iranian Kurdistan).[146] This has been the pretext for numerous Turkish attacks on the Kurdistan region of Iraq.

In June 2007, Turkey estimated there to be over 3,000 PKK fighters in Iraqi Kurdistan.[147]

History

Beginnings

In 1977, a small group under Öcalan's leadership released a declaration on Kurdish identity in Turkey. The group, which called itself the Revolutionaries of Kurdistan also included Ali Haydar Kaytan, Cemil Bayik, Haki Karer and Kemal Pir.[148] The group decided in 1974[82] to start a campaign for Kurdish rights. Cemil Bayik was sent to Urfa, Kemal Pir to Mus, Haki Karer to Batman, and Ali Haydar Kaytan to Tunceli. They then started student organisations which talked to local workers and farmers about Kurdish rights.[148]

In 1977, an assembly was held to evaluate the political activities. The assembly included 100 people, from different backgrounds and several representatives from other leftist organisations. In spring 1977, Abdullah Öcalan travelled to Mount Ararat, Erzurum, Tunceli, Elazig, Antep, and other cities to make the public aware of the Kurdish issue. This was followed by a Turkish government crackdown against the organisation. On 18 March 1977, Haki Karer was assassinated in Antep. During this period, the group was also targeted by the Turkish ultranationalist organization, the Nationalist Movement Party's Grey Wolves. Some wealthy Kurdish landowners targeted the group as well, killing Halil Çavgun on 18 May 1978, which resulted in large Kurdish meetings in Erzurum, Dersim, Elazig, and Antep.[148]

The founding Congress of the PKK was held on 27 November 1978 in Fis, a village near the city of Lice. During this congress the 25 people present decided to found the Kurdistan Workers' Party. The Turkish state, Turkish rightist groups, and some Kurdish landowners continued their attacks on the group. In response, the PKK employed armed members to protect itself, which got involved in the fighting between leftist and rightist groups in Turkey (1978–1980) at the side of the leftists,[148] during which the right-wing Grey Wolves militia killed 109 and injured 176 Alevi Kurds in the town of Kahramanmaraş on 25 December 1978 in what would become known as the Maraş Massacre.[149] In Summer 1979, Öcalan travelled to Syria and Lebanon where he made contacts with Syrian and Palestinian leaders.[148] After the Turkish coup d'état on 12 September 1980 and a crackdown which was launched on all political organisations,[150] during which at least 191 people were killed[151] and half a million were imprisoned,[152][note 2] most of the PKK withdrew into Syria and Lebanon. Öcalan himself went to Syria in September 1980 with Kemal Pir, Mahsum Korkmaz, and Delil Dogan being sent to set up an organisation in Lebanon. Some PKK fighters allegedly took part in the 1982 Lebanon War on the Syrian side.[148]

The Second PKK Party Congress was then held in Daraa, Syria, from 20 to 25 August 1982. Here it was decided that the organisation would return to Turkey to start an armed guerilla war there for the creation of an independent Kurdish state. Meanwhile, they prepared guerrilla forces in Syria and Lebanon to go to war. However, many PKK leaders were arrested in Turkey and sent to Diyarbakir Prison. The prison became the site of much political protest.[148] (See also Torture in Turkey#Deaths in custody.)

In Diyarbakır Prison, PKK member Mazlum Doğan burned himself to death on March 21, 1982 in protest at the treatment in prison. Ferhat Kurtay, Necmi Önen, Mahmut Zengin and Eşref Anyık followed his example on May 17. On July 14, PKK members Kemal Pir, M. Hayri Durmuş, Ali Çiçek and Akif Yılmaz started a hunger strike in Diyarbakır Prison.[154] Kemal Pir died on September 7, M. Hayri Durmuş on the 12th, Akif Yılmaz on the 15th, and Ali Çiçek on the 17th. On April 13, 1984, a 75-day hunger-strike started in Istanbul. As a result, four prisoners—Abdullah Meral, Haydar Başbağ, Fatih Ökütülmüş, and Hasan Telci—died.[155]

On 25 October 1986, the third Congress was held in Beqaa Valley, Lebanon. The lack of discipline, the growing internal criticism and splinter groups within the organization were getting out of hand. This had led the organisation to execute some internal critics, especially ex-members who had joined Tekosin, a rival Marxist–Leninist organization. Abdullah Öcalan, the leader of the organization, heavily criticized the leaders responsible for the guerrilla forces during the early 1980s and warned others of a similar fate, with death penalty, if they join rival groups or refuse to obey the orders. Additionally, the military defeats and the reality of the armed conflict were eroding the notions of a Greater Kurdistan, the organization's primary goal. The cooperation with rogue partners, criminal regimes and some dictators, such as Saddam Hussein who gave them weapons in exchange for information on the Kurdistan Democratic Party of Masoud Barzani during the genocidal al Anfal campaign, had tarnished the organization's image. During the Congress, the leaders decided to advance the armed struggle, increase the number of the fighters and dissolve the HRK, which was replaced by Kurdistan Popular Liberation Army (ARGK). A newly established Mahsum Korkmaz Academy, a political and military instruction academy, replaced the name of Helve Camp, and a new military draft law was approved, which obliged every family to send someone to the guerrilla forces.[156][157][158]

The decisions that were taken during the third Congress transformed the PKK from a Leninist organization into an organization in which Abdullah Öcalan gained all power and special status, so-called Önderlik (leadership). Some of the reasons why Abdullah Öcalan took power from the other leaders, such as Murat Karayilan, Cemil Bayik and Duran Kalkan, were growing internal conflict and the organization's inability to stop it. According to Michael Gunter, Abdullah Öcalan, before capturing the power, had allegedly carried out a purge against many rival PKK members, tortured and forced them to confess they were traitors before ordered to be executed. Ibrahim Halik, Mehmet Ali Cetiner, Mehmet Result Altinok, Saime Askin, Ayten Yildirim and Sabahattin Ali were some of the victims. Later in 2006, Abdullah Öcalan denied the accusations and stated in his book that both Mahsum Korkmaz, the first supreme military commander of the PKK, and Engin Sincer, a high ranked commander, likely died as a result of internal conflicts and described the perpetrators as "gangs". The leaked reports, however, had revealed the authoritarian personality of Öcalan who had brutally suppressed dissent and purged opponents since the early 1980s. According to David L. Philips, up to sixty PKK members were executed in 1986, including Mahsum Korkmaz, who he believes was murdered on 28 March 1986. Between the 1980 and 1990, the organization targeted the defectors and assassinated two of them in Sweden, two in Netherlands, three in Germany and one in Denmark.[157][159]

In 1990, during the fourth Congress, the PKK under pressure and criticism decided to end the forced military conscription, the military draft law it had implemented during the third Congress. Some members also demanded the end of attacks on civilians which reportedly reduced the number of attacks against the civilians for a few years. The organization's attempts to take into the account the demands and criticism of its support base had helped it to increase its popularity among some Kurds. According to Stanton, the PKK's relationship with its civilian supporters likely created incentives for the government to use terrorism against some Kurdish citizens. However, despite a numerous of changes, the organization failed to end the violent attacks on civilians and continued to use terrorism as one of its weapons against the government.[160]

First insurgency

1984–1993

The PKK launched its armed insurgency on 15 August 1984[148][161] with armed attacks on Eruh and Semdinli. During these attacks 1 gendarmerie soldier was killed and 7 soldiers, 2 policemen and 3 civilians were injured. It was followed by a PKK raid on a police station in Siirt, two days later.[162]

In the early 1990s, President Turgut Özal agreed to negotiations with the PKK, the events of the 1991 Gulf War having changed some of the geopolitical dynamics in the region. Apart from Özal, himself half-Kurdish, few Turkish politicians were interested in a peace process, nor was more than a part of the PKK itself.[163] In February 1991, during the presidency of Özal, the prohibition of Kurdish music was cancelled.[164] In 1992, however, Turkey, backed by United States and Peshmergas of Kurdistan Democratic Party and Patriotic Union of Kurdistan, launched Operation Northern Iraq, a cross-border operation between 9 October and 1 November against the PKK using more than 300,000 troops. Thousands of local Peshmergas with the support of more than 20,000 Turkish troops who had crossed the Iraqi border, tried to drive 10,000 PKK guerrillas from Northern Iraq. Despite the heavy casualties, the PKK managed to maintain its presence in Northern Iraq and a cease fire agreement was reached between the PKK and KRG. In 1993, Özal started to work on the peace plans with the former finance minister Adnan Kahveci and the General Commander of the Turkish Gendarmerie, Eşref Bitlis.[165]

Unilateral cease-fire 1993

Negotiations led to a unilateral cease-fire by the PKK on 17 March 1993. Accompanied by Jalal Talabani, Öcalan stated that the PKK no longer wants a partition from Turkey but peace,[166] dialogue and free political action within the framework of a democratic state for the Kurds in Turkey. Süleyman Demirel, the prime minister of Turkey at the time, refused to negotiate with the PKK, but also stated that the forced assimilation was the wrong approach towards the Kurds.[167] Several Kurdish politicians supported the in cease fire and Kemal Burkay and also Ahmet Türk from the People's Labor Party (HEP) were present at the press conference in Barelias, Lebanon, where it was prolonged.[166] With the PKK's ceasefire declaration in hand, Özal was planning to propose a major pro-Kurdish reform package at the next meeting of the National Security Council. The president's death on 17 April led to the postponement of that meeting, and the plans were never presented.[168] After the Turkish army attacked the PKK the 19 May in 1993 in Kulp[169] the cease fire came to an end and on the 24 May the PKK ambushed a Konvoy of the Turkish military. The former PKK commander Şemdin Sakık maintains the attack was part of the Doğu Çalışma Grubu's coup plans.[170] On the 8 June 1993, Öcalan announced the end of the ceasefire by the PKK.[171]

Insurgency 1993–1994

Under the new Presidency of Süleyman Demirel and Premiership of Tansu Çiller, the Castle Plan (to use any and all means to solve the Kurdish question using violence), which Özal had opposed, was enacted, and the peace process abandoned.[172] Some journalists and politicians maintain that Özal's death (allegedly by poison) along with the assassination of a number of political and military figures supporting his peace efforts, was part of a covert military coup in 1993 aimed at stopping the peace plans.

To counter the growing force of the PKK the Turkish military started new counter-insurgency strategies between 1992 and 1995. To deprive the rebels of a logistical base of operations and allegedly punishing local people supporting the PKK the military carried out de-forestation of the countryside and destroyed over 3,000 Kurdish villages, causing at least 2 million refugees. Most of these villages were evacuated, but other villages were burned, bombed, or shelled by government forces, and several entire villages were obliterated from the air. While some villages were destroyed or evacuated, many villages were brought to the side of the Turkish government, which offered salaries to local farmers and shepherds to join the Village Guards, which would prevent the PKK from operating in these villages, while villages which refused were evacuated by the military. These tactics managed to drive the rebels from the cities and villages into the mountains, although they still often launched reprisals on pro-government villages, which included attacks on civilians.[173]

Unilateral ceasefire 1995-1996

In December 1995, the PKK announced a second unilateral ceasefire, ahead of the general elections on 24 December 1995, thought to give the new Turkish Government time to articulate a more peaceful approach to the conflict between the PKK and Turkey. During the ceasefire, the political and civil society organized several peace initiatives in support of a solution to the conflict. But in May 1996, an attempt to murder Abdullah Öcalan occurred in Damascus and in June of the same year the Turkish military began to pursue the PKK in Iraqi Kurdistan.[174] The PKK announced the end of the unilateral ceasefire on the 16 August 1996, mentioning it was still ready for peace negotiations as a political solutions.[174]

Insurgency 1996–1999

However, the turning point in the conflict[175] came in 1998, when, after political pressure and military threats[176] from Turkey, the PKK's leader, Abdullah Öcalan, was forced to leave Syria, where he had been in exile since September 1980. He first went to Russia, then to Italy and Greece. He was eventually brought to the Greek embassy in Nairobi, Kenya, where he was arrested on 15 February 1999 at the airport in a joint MİT-CIA operation and brought to Turkey,[177] which resulted in major protests by Kurds worldwide.[176] Three Kurdish protestors were shot dead when trying to enter the Israeli consulate in Berlin to protest alleged Israeli involvement in the capture of Abdullah Öcalan.[178] Although the capture of Öcalan ended a third cease-fire which Öcalan had declared on 1 August 1998, on 1 September 1999[130] the PKK declared a unilateral cease-fire which would last until 2004.[82]

Unilateral cease-fire 1999–2003

After the unilateral cease-fire the PKK declared in September 1999, their forces fully withdrew from the Republic of Turkey and set up new bases in the Qandil Mountains of Iraq[162] and in February 2000 they declared the formal end of the war.[176] After this, the PKK said it would switch its strategy to using peaceful methods to achieve their objectives. In April 2002 the PKK changed its name to KADEK (Kurdistan Freedom and Democracy Congress), claiming the PKK had fulfilled its mission and would now move on as purely political organisation.[132] In October 2003 the KADEK announced its dissolution and declared the creation of a new organisation: KONGRA-GEL (Kurdistan Peoples Congress).[179]

Offers by the PKK for negotiations were ignored by the Turkish government,[132] which claimed, the KONGRA-GEL continued to carry out armed attacks in the 1999–2004 period, although not on the same scale as before September 1999. They also blame the KONGRA-GEL for Kurdish riots which happened during the period.[162] The PKK argues that they only defended themselves as they claim the Turkish military launched some 700 raids against their bases militants, including in Northern Iraq.[161] Also, despite the KONGRA-GEL cease-fire, other groups continued their armed activities, the PŞK for instance, tried to use the cease-fire to attract PKK fighters to join their organisation.[180] The Kurdistan Freedom Hawks (TAK) were formed during this period by radical KONGRA-GEL commanders, dissatisfied with the cease-fire.[181] The period after the capture of Öcalan was used by the Turkish government to launch major crackdown operations against the Turkish Hezbollah (Kurdish Hezbollah), arresting 3,300 Hizbullah members in 2000, compared to 130 in 1998, and killing the group's leader Hüseyin Velioğlu on 13 January 2000.[182][183][184] During this phase of the war at least 145 people were killed during fighting between the PKK and security forces.[185]

After the AK Party came to power in 2002, the Turkish state started to ease restrictions on the Kurdish language and culture.[186]

From 2003 to 2004 there was a power struggle inside the KONGRA-GEL between a reformist wing which wanted the organisation to disarm completely and a traditionalist wing which wanted the organisation to resume its armed insurgency once again.[162][187] The conservative wing of the organisation won this power struggle[162] forcing reformist leaders such as Kani Yilmaz, Nizamettin Tas and Abdullah Öcalan's younger brother Osman Öcalan to leave the organisation.[187] The three major traditionalist leaders, Murat Karayilan, Cemil Bayik and Fehman Huseyin formed the new leadership committee of the organisation.[188] The new administration decided to restart the insurgency, because they claimed that without guerillas the PKK's political activities would remain unsuccessful.[132][162] This came as the pro-Kurdish People's Democracy Party (HADEP) was banned by the Turkish Supreme Court on 13 March 2003[189] and its leader Murat Bolzak was imprisoned.[190]

In April 2005, KONGRA-GEL reverted its name back to PKK.[179] Because not all of the KONGRA-GEL's elements reverted, the organisation has also been referred to as the New PKK.[191] The KONGRA-GEL has since become the Legislative Assembly of the Koma Civakên Kurdistan, an umbrella organisation which includes the PKK and is used as the group's urban and political wing. Ex-DEP member Zübeyir Aydar is the President of the KONGRA-GEL.[192]

Through the cease-fire years 2000, 2001, 2002 and 2003, some 711 people were killed according to the Turkish government.[193] The Uppsala Conflict Data Program put casualties during these years at 368 to 467 killed.[194]

Insurgency from 2004–2012

On 1 September 2003 the PKK declared the end of the cease-fire but they waited with a new insurgency until mid 2004.[195] On 1 June 2004, the PKK resumed its armed activities because they claimed Turkish government was ignoring their calls for negotiations and was still attacking their forces.[132][162] The government claimed that in that same month some 2,000 Kurdish guerrillas entered Turkey via Iraqi Kurdistan.[82] The PKK, lacking a state sponsor or the kind of manpower they had in the 90s, was forced to take up new tactics. As result, it reduced the size of its field units from 15–20 militants to 6–8 militants. It also avoided direct confrontations and relied more on the use of mines, snipers and small ambushes, using hit and run tactics.[196] Another change in PKK-tactics was that the organisation no longer attempted to control any territory, not even after dark.[197] Nonetheless, violence increased throughout both 2004 and 2005[82] during which the PKK was said to be responsible for dozens of bombings in Western Turkey throughout 2005.[38] Most notably the 2005 Kuşadası minibus bombing, which killed 5 and injured 14 people,[198] although the PKK denied responsibility.[199]

In March 2006 heavy fighting broke out around Diyarbakir between the PKK and Turkish security forces, as well as large riots by PKK supporters, as result the army had to temporary close the roads to Diyarbakır Airport and many schools and businesses had to be shut down.[82] In August, the Kurdistan Freedom Hawks (TAK), which vowed to "turn Turkey into hell",[200] launched a major bombing campaign. On 25 August two coordinated low-level blasts targeted a bank in Adana, on 27 August a school in Istanbul was targeted by a bombing, on 28 August there were three coordinated attacks in Marmaris and one in Antalya targeting the tourist industry[82] and on 30 August there was a TAK bombing in Mersin.[201] These bombings were condemned by the PKK,[42] which declared its fifth cease-fire on 1 October 2006,[130] which slowed down the intensity of the conflict. Minor clashes, however, continued in the South East due to Turkish counter-insurgency operations. In total, the conflict claimed over 500 lives in 2006.[82] 2006 also saw the PKK assassinate one of their former commanders, Kani Yilmaz, in February, in Iraq.[162]

In May 2007, there was a bombing in Ankara that killed 6[202][203][204][205] and injured 121 people.[202] The Turkish government alleged the PKK was responsible for the bombing.[206] On 4 June, a PKK suicide bombing in Tunceli killed seven soldiers and wounded six at a military base.[207] Tensions across the Iraqi border also started playing up as Turkish forces entered Iraq several times in pursuit of PKK fighting and In June, as 4 soldiers were killed by landmines, large areas of Iraqi Kurdistan were shelled which damaged 9 villages and forced residents to flee.[208] On 7 October 2007, 40–50 PKK fighters[196] ambushed an 18-man Turkish commando unit in the Gabar mountains, killing 15 commandos and injuring three,[209] which made it the deadliest PKK attack since the 1990s.[196] In response a law was passed allowing the Turkish military to take action inside Iraqi territory.[210] Than on 21 October 2007, 150–200 militants attacked an outpost, in Dağlıca, Yüksekova, manned by a 1950strong infantry battalion. The outpost was overrun and the PKK killed 12, wounded 17 and captured 8 Turkish soldiers. They then withdrew into Iraqi Kurdistan, taking the 8 captive soldiers with them. The Turkish military claimed to have killed 32 PKK fighters in hot pursuit operations, after the attack, however this was denied by the PKK and no corpses of PKK militants were produced by the Turkish military.[196] The Turkish military responded by bombing PKK bases on 24 October[211] and started preparing for a major cross-border military operation.[209]

This major cross-border offensive, dubbed Operation Sun, started on 21 February 2008[212] and was preceded by an aerial offensive against PKK camps in northern Iraq, which began on 16 December 2007.[213][214] Between 3,000 and 10,000 Turkish forces took part in the offensive.[212] According to the Turkish military around 230 PKK fighters were killed in the ground offensive, while 27 Turkish forces were killed. According to the PKK, over 125 Turkish forces were killed, while PKK casualties were in the tens.[215] Smaller scale Turkish operations against PKK bases in Iraqi Kurdistan continued afterwards.[216] On 27 July 2008, Turkey blamed the PKK for an Istanbul double-bombing which killed 17 and injured 154 people. The PKK denied any involvement.[217] On 4 October, the most violent clashes since the October 2007 clashes in Hakkari erupted as the PKK attacked the Aktutun border post in Şemdinli in the Hakkâri Province, at night. 15 Turkish soldiers were killed and 20 were injured, meanwhile 23 PKK fighters were said to be killed during the fighting.[218] On 10 November, the Iranian Kurdish insurgent group PJAK declared it would be halting operations inside Iran to start fighting the Turkish military.[219][220]

At the start of 2009 Turkey opened its first Kurdish-language TV-channel, TRT 6,[221] and on 19 March 2009 local elections were held in Turkey in which the pro-Kurdish Democratic Society Party (DTP) won majority of the vote in the South East. Soon after, on 13 April 2009, the PKK declared its sixth ceasefire, after Abdullah Öcalan called on them to end military operations and prepare for peace.[130] The following day the Turkish authorities arrested 53 Kurdish politicians of the Democratic Society Party (DTP).[222] In September Turkey's Erdoğan-government launched the Kurdish initiative, which included plans to rename Kurdish villages that had been given Turkish names, expand the scope of the freedom of expression, restore Turkish citizenship to Kurdish refugees, strengthen local governments, and extend a partial amnesty for PK fighters.[223] But the plans for the Kurdish initiative where heavily hurt after the DTP was banned by the Turkish constitutional court[224] on 11 December 2009 and its leaders were subsequently put on trial for terrorism.[225] A total of 1,400 DTP members were arrested and 900 detained in the government crackdown against the party.[226] This caused major riots by Kurds all over Turkey and resulted in violent clashes between pro-Kurdish and security forces as well as pro-Turkish demonstrators, which resulted in several injuries and fatalities.[224] On 7 December the PKK launched an ambush in Reşadiye which killed seven and injured three Turkish soldiers, which became the deadliest PKK attack in that region since the 1990s.[227][228]

On 1 May 2010 the PKK declared an end to its cease-fire,[229] launching an attack in Tunceli that killed four and injured seven soldiers.[230] On 31 May, Abdullah Öcalan declared an end to his attempts at re-approachment and establishing dialogue with the Turkish government, leaving PKK top commanders in charge of the conflict. The PKK then stepped up its armed activities,[231] starting with a missile attack on a navy base in İskenderun, killing 7 and wounding 6 soldiers.[232] On 18 and 19 June, heavy fighting broke out that resulted in the death of 12 PKK fighters, 12 Turkish soldiers and injury of 17 Turkish soldiers, as the PKK launched three separate attacks in Hakkari and Elazig provinces.[233][234]

Another major attack in Hakkari occurred on 20 July 2010, killing six and wounding seventeen Turkish soldiers, with one PKK fighter being killed.[235] The next day, Murat Karayilan, the leader of the PKK, announced that the PKK would lay down its arms if the Kurdish issue would be resolved through dialogue and threatened to declare independence if this demand was not met.[236][237] Turkish authorities claimed they had killed 187 and captured 160 PKK fighters by 14 July.[238] By 27 July, Turkish news sources reported the deaths of over 100 security forces, which exceeded the entire 2009 toll.[239] On 12 August, however, a ramadan cease-fire was declared by the PKK. In November the cease-fire was extended until the Turkish general election on 12 June 2011, despite alleging that Turkey had launched over 80 military operations against them during this period.[130] Despite the truce, the PKK responded to these military operations by launching retaliatory attacks in Siirt and Hakkari provinces, killing 12 Turkish soldiers.[240]

The cease-fire was revoked early, on 28 February 2011.[241] Soon afterwards three PKK fighters were killed while trying to get into Turkey through northern Iraq.[242] In May, counter-insurgency operations left 12 PKK fighters and 5 soldiers dead. This then resulted in major Kurdish protests across Turkey as part of a civil disobedience campaign launched by the pro-Kurdish Peace and Democracy Party (BDP),[243] during these protests 2 people were killed, 308 injured and 2,506 arrested by Turkish authorities.[244] The 12 June elections saw a historical performance for the pro-Kurdish Peace and Democracy Party (BDP) which won 36 seats in the South-East, which was more than the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP), which won only 30 seats in Kurdish areas.[245] However, six of the 36 elected BDP deputies remain in Turkish jails as of June 2011.[246] One of the six jailed deputies, Hatip Dicle, was then stripped of his elected position by the constitutional court, after which the 30 free MPs declared a boycott of Turkish parliament.[247] The PKK intensified its campaign again, in July killing 20 Turkish soldiers in two weeks, during which at least 10 PKK fighters were killed.[248] On 17 August 2011, the Turkish Armed Forces launched multiple raids against Kurdish rebels, striking 132 targets.[249] Turkish military bombed PKK targets in northern Iraq in six days of air raids, according to General Staff, where 90–100 PKK Soldiers were killed, and at least 80 injured.[250] From July to September Iran carried out an offensive against the PJAK in Northern Iraq, which resulted in a cease-fire on 29 September. After the cease-fire the PJAK withdrew its forces from Iran and joined with the PKK to fight Turkey. Turkish counter-terrorism operations reported a sharp increase of Iranian citizens among the insurgents killed in October and November, such as the six PJAK fighters killed in Çukurca on 28 October.[251] On 19 October, twenty-six Turkish soldiers were killed[252] and 18 injured[253] in 8 simultaneous PKK attacks in Cukurca and Yuksekova, in Hakkari provieen 10,000 and 15,000 full-time, which is the highest it has ever been.[254]

In summer 2012, the conflict with the PKK took a violent curve, in parallel with the Syrian civil war[255] as President Bashar al-Assad ceded control of several Kurdish cities in Syria to the PYD, the Syrian affiliate of the PKK, and Turkey armed ISIS and other Islamic groups against Kurds.[256] Turkish foreign minister Ahmet Davutoglu accused the Assad government of arming the group.[257] In June and August there were heavy clashes in Hakkari province, described as the most violent in years.[258] as the PKK attempted to seize control of Şemdinli and engage the Turkish army in a "frontal battle" by blocking the roads leading to the town from Iran and Iraq and setting up DShK heavy machine guns and rocket launchers on high ground to ambush Turkish motorized units that would be sent to re-take the town. However the Turkish army avoided the trap by destroying the heavy weapons from the air and using long range artillery to root out the PKK. The Turkish military declared operation was ended successfully on 11 August, claiming to have killed 115 guerrillas and lost only six soldiers and two village guards.[259] On 20 August, eight people were killed and 66 wounded by a deadly bombing in Gaziantep.[260] According to the KCK 400 incidents of shelling, air bombardment and armed clashes occurred in August.[102] On 24 September, Turkish General Necdet Özel claimed that 110 Turkish soldiers and 475 PKK militants had been killed since the start of 2012.[261]

Peace Process 2012-2015

On 28 December 2012, in a television interview upon a question of whether the government had a project to solve the issue, Erdoğan said that the government was conducting negotiations with jailed rebel leader Öcalan.[262] Negotiations were initially named as Solution Process (Çözüm Süreci) in public. While negotiations were going on, there were numerous events that were regarded as sabotage to derail the talks: The assassination of the PKK administrators Sakine Cansız, Fidan Doğan and Leyla Söylemez in Paris,[263] revealing Öcalan's talks with the pro-Kurdish party Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP) to the public via the Milliyet newspaper[264] and finally, the bombings of the Justice Ministry of Turkey and Erdoğan's office at the Ak Party headquarters in Ankara.[265] However, both parties vehemently condemned all three events as they occurred and stated that they were determined anyway. Finally on 21 March 2013, after months of negotiations with the Turkish Government, Abdullah Ocalan's letter to people was read both in Turkish and Kurdish during Nowruz celebrations in Diyarbakır. The letter called a cease-fire that included disarmament and withdrawal from Turkish soil and calling an end to armed struggle. PKK announced that they would obey, stating that the year of 2013 is the year of solution either through war or through peace. Erdoğan welcomed the letter stating that concrete steps will follow PKK's withdrawal.[133]

On 25 April 2013, PKK announced that it would be withdrawing all its forces within Turkey to Northern Iraq.[266] According to the Turkish government[267] and the Kurds[268] and most of the press,[269] this move marks the end of 30-year-old conflict. Second phase which includes constitutional and legal changes towards the recognition of human rights of the Kurds starts simultaneously with withdrawal.

Escalation

On 6 and 7 October 2014, riots erupted in various cities in Turkey for protesting the Siege of Kobane. The Kurds accused the Turkish government of supporting ISIS and not letting people send support for Kobane Kurds. Protesters were met with tear gas and water cannons. 37 people were killed in protests.[270] During these protests, there were deadly clashes between PKK and Hizbullah sympathizers.[271] 3 soldiers were killed by PKK in January 2015,[272] as a sign of rising tensions in the country.

2015–present

In June 2015, the main Syrian Kurdish militia, YPG, and the Turkey's main pro-Kurdish party, HDP, accused Turkey of allowing Islamic State (ISIL) soldiers to cross its border and attack the Kurdish city of Kobanî in Syria.[273] The conflict between Turkey and PKK escalated following the 20 July 2015 Suruç bombing attack on progressive activists, which was claimed by ISIL. During the 24–25 July 2015 Operation Martyr Yalçın, Turkey bombed alleged PKK bases in Iraq and PYD bases in Syria's Kurdish region Rojava, purportedly retaliating the killing of two policeman in the town of Ceylanpınar (which the PKK denied carrying out) and effectively ending the cease-fire (after many months of increasing tensions).[274][275][276] Turkish warplanes also bombed YPG bases in Syria.[277]

Violence soon spread throughout Turkey. Many Kurdish businesses were destroyed by mobs.[278] The headquarters and branches of the pro-Kurdish Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP) were also attacked.[279] There are reports of civilians being killed in several Kurdish-populated towns and villages.[280] The Council of Europe raised their concerns over the attacks on civilians and the 4 September 2015 blockade of Cizre.[281]

But also the Kurdish rebel fighters did not sit still: a Turkish Governor claimed that Kurdish assailants had fired on a police vehicle in Adana in September 2015, killing two officers, and some unspecified "clash" with PKK rebels purportedly took place in Hakkâri Province. President Erdogan claimed that between 23 July and late September, 150 Turkish officers and 2,000 Kurdish rebels had been killed.[282] In December 2015, Turkish military operations in the Kurdish regions of southeastern Turkey had killed hundreds of civilians, displaced hundreds of thousands and caused massive destruction in residential areas.[283] According to the Human Rights Watch (HRW) report, "Local human rights groups have recorded well over 100 civilian deaths and multiple injuries."[284]

The spring of 2016 saw the seasonal uptick in combat activity. In May, a Turkish Bell AH-1 SuperCobra helicopter was documented shot down by a PKK-fired Russian made MANPADS.[285]

On May 6, 2016, HBDH, an umbrella organization built around the Kurdish PKK, attacked a Gendarmerie General Command base in Giresun Province in northeastern Turkey. According to news reports, a roadside bomb exploded, targeting a Gendarmerie vehicle.[286] HDBH claimed responsibility for the attack on May 8, stating that three gendarmes died in the attack, as well as the Base Commander, who was the intended target.[287] the Joint Command of the HBDH has claimed responsibility for several more attacks in the region, primarily targeting Turkish soldiers or gendarmes. The tactics employed by the alliance are very similar to those used by the PKK. The most notable attack came on 19 July 2016, just 4 days after the 2016 Turkish coup d'état attempt. HBDH reported that they had killed 11 Turkish riot police in Trabzon Province at 08:30 that morning.[288] The HBDH report is consistent in time and location to an attack reported by Doğan News Agency, in which "unknown assailants" fired on a police checkpoint. This report states that 3 officers were killed and 5 were injured, along with a civilian.[289]

In January 2018, the Turkish military and its Free Syrian Army and Sham Legion allies began a cross-border operation in the Kurdish-majority Afrin Canton in Northern Syria, against the Kurdish-led Democratic Union Party in Syria (PYD) and the U.S.-supported YPG Kurdish militia.[290][291] In March 2018, Turkey launched military operations to eliminate the Kurdish PKK fighters in northern Iraq.[292]

.jpg)

In October 2019, the Turkish force launched an operation against Syrian Kurds in the Northern Syria which has been termed Operation Peace Spring.[293][294]

Serhildan

The Serhildan, or people's uprising,[295] started on 14 March 1990, Nusaybin during the funeral of[296] 20-year-old PKK fighter Kamuran Dundar, who along with 13 other fighters was killed by the Turkish military after crossing into Turkey via Syria several days earlier. Dundar came from a Kurdish nationalist family which claimed his body and held a funeral for him in Nusaybin in which he was brought to the city's main mosque and 5000 people which held a march. On the way back the march turned violent and protesters clashed with the police, during which both sides fired upon each other and many people were injured. A curfew was then placed in Nusaybin, tanks and special forces were brought in and[295] some 700 people were arrested.[296] Riots spread to nearby towns[295] and in Cizre over 15,000 people, constituting about half the town's population took part in riots in which five people were killed, 80 injured and 155 arrested.[296] Widespread riots took place throughout the Southeast on Nowruz, the Kurdish new-year celebrations, which at the time were banned.[296] Protests slowed down over the next two weeks as many started to stay home and Turkish forces were ordered not to intervene unless absolutely necessarily[295] but factory sit-ins, go-slows, work boycotts and "unauthorized" strikes were still held although in protest of the state.[296]

Protests are often held on 21 March, or Nowruz.[297] Most notably in 1992, when thousands of protesters clashed with security forces all over the country and where the army allegedly disobeyed an order from President Suleyman Demirel not to attack the protest.[296] In the heavy violence that ensued during that year's Nowroz protest some 55[296] people were killed, mainly in Şırnak (26 killed), Cirze (29 killed) and Nusaybin (14 killed) and it included a police officer and a soldier. Over 200 people were injured[298] and another 200 were arrested.[296] According to Governor of Şırnak, Mustafa Malay, the violence was caused by 500 to 1,500 armed rebels which he alleged, entered the town during the festival. However, he conceded that "the security forces did not establish their targets properly and caused great damage to civilian houses."[299]

Since Abdullah Öcalan's capture on 15 February 1998, protests are also held every year on that date.[297]

Kurdish political movement

| Name | Short | Leader | Active |

|---|---|---|---|

| People's Labor Party | HEP | Ahmet Fehmi Işıklar | 1990–1993 |

| Democracy Party | DEP | Yaşar Kaya | 1993–1994 |

| People's Democracy Party | HADEP | Murat Bozlak | 1994–2003 |

| Democratic People's Party | DEHAP | Tuncer Bakırhan | 1997–2005 |

| Democratic Society Movement | DTH | Leyla Zana | 2005 |

| Democratic Society Party | DTP | Ahmet Türk | 2005–2009 |

| Peace and Democracy Party | BDP | Gültan Kışanak, Selahattin Demirtaş | 2008–2014 |

| Democratic Regions Party | DBP | Emine Ayna, Kamûran Yüksek | 2014–present |

| Peoples' Democratic Party | HDP | Pervin Buldan, Sezai Temelli | 2012–present |

On 7 June 1990, seven members of the Grand National Assembly of Turkey who were expelled from the Social Democratic People's Party (SHP), together formed the People's Labor Party (HEP) and were led by Ahmet Fehmi Işıklar. The Party was banned in July 1993 by the Constitutional Court of Turkey for promoting separatism.[300] The party was succeeded by the Democracy Party, which was founded in May 1993. The Democracy Party was banned on 16 June 1994 for promoting Kurdish nationalism[300] and four of the party's members: Leyla Zana, Hatip Dicle, Orhan Doğan and Selim Sadak were sentenced to 14 years in prison. Zana was the first Kurdish woman to be elected into parliament.[301] However, she sparked a major controversy by saying, during her inauguration into parliament, "I take this oath for the brotherhood between the Turkish people and the Kurdish people." In June 2004, after spending 10 years in jail, a Turkish court ordered the release of all four prisoners.[302] In May 1994, Kurdish lawyer Murat Bozlak formed the People's Democracy Party (HADEP),[300] which won 1,171,623 votes, or 4.17% of the national vote during the general elections on 24 December 1995[303] and 1,482,196 votes or 4.75% in the elections on 18 April 1999, but it failed to win any seats due to the 10% threshold.[304] During local elections in 1999 they won control over 37 municipalities and gained representation in 47 cities and hundreds of districts. In 2002 the party became a member of Socialist International. After surviving a closure case in 1999, HADEP was finally banned on 13 March 2003 on the grounds that it had become a "centre of illegal activities which included aiding and abetting the PKK". The European Court of Human Rights ruled in 2010 that the ban violated article 11 of the European Convention on Human Rights which guarantees freedom of association.[305] The Democratic People's Party (DEHAP) was formed on 24 October 1997 and succeeded HADEP.[306] DEHAP won 1,955,298 votes or 6,23% during the November 3, 2002 general election.[307] However, it performed disappointingly during the March 28, 2004 local elections, where their coalition with the SHP and the Freedom and Solidarity Party (ÖDP) only managed to win 5.1% of the vote, only winning in Batman, Hakkâri, Diyarbakır and Şırnak Provinces, the majority of Kurdish voters voting for the AKP.[308] After being released in 2004 Leyla Zana formed the Democratic Society Movement (DTH), which merged with the DEHAP into the Democratic Society Party (DTP) in 2005[295] under the leadership of Ahmet Türk.[309]

_Celebration_-_Istanbul.jpg)

The Democratic Society Party decided to run their candidates as independent candidates during the June 22, 2007 general elections, to get around the 10% threshold rule. Independents won 1,822,253 votes or 5.2% during the elections, resulting in a total of 27 seats, 23 of which went to the DTP.[310] The party performed well during the March 29, 2009 local elections, however, winning 2,116,684 votes or 5.41% an doubling the number of governors from four to eight and increasing the number of mayors from 32 to 51.[311] For the first time they won a majority in the southeast and, aside from the Batman, Hakkâri, Diyarbakır and Şırnak provinces which DEHAP had won in 2004, the DTP managed to win Van, Siirt and Iğdır Provinces from the AKP.[312] On 11 December 2009, the Constitutional Court of Turkey voted to ban the DTP, ruling that the party had links to the PKK just like in case of previous closed Kurdish parties[313] and authorities claimed that it is seen as guilty of spreading "terrorist propaganda".[314] Chairman Ahmet Türk and legislator Aysel Tuğluk were expelled from Parliament, and they and 35 other party members were banned from joining any political party for five years.[315] The European Union released a statement, expressing concern over the court's ruling and urging Turkey to change its policies towards political parties.[316] Major protests erupted throughout Kurdish communities in Turkey in response to the ban.[313] The DTP was succeeded by the Peace and Democracy Party (BDP), under the leadership of Selahattin Demirtaş. The BDP called on its supporters to boycott the Turkish constitutional referendum on 12 September 2010 because the constitutional change did not meet minority demands. Gültan Kışanak, the BDP co-chair, released a statement saying that "we will not vote against the amendment and prolong the life of the current fascist constitution. Nor will we vote in favour of the amendments and support a new fascist constitution."[317] Due to the boycott Hakkâri (9.05%), Şırnak (22.5%), Diyarbakır (34.8%), Batman (40.62%), Mardin (43.0%), Van (43.61), Siirt (50.88%), Iğdır (51.09%), Muş (54.09%), Ağrı (56.42%), Tunceli (67.22%), Şanlıurfa (68.43%), Kars (68.55%) and Bitlis Province (70.01%) had the lowest turnouts in the country, compared to a 73.71% national average. Tunceli was the only Kurdish majority province where a majority of the population voted "no" during the referendum.[318] During the June 12, 2011 national elections the BDP nominated 61 independent candidates, winning 2,819,917 votes or 6.57% and increasing its number of seats from 20 to 36. The BDP won the most support in Şırnak (72.87%), Hakkâri (70.87%), Diyarbakır (62.08%) and Mardin (62.08%) Provinces.[314]

Casualties

According to figures released by the Anadolu Agency, citing a Turkish security source, from 1984 to August 2015, there were 36,345 deaths in the conflict. This included 6,741 civilians, 7,230 security forces (5,347 soldiers, 1,466 village guards and 283 policemen) and 22,374 PKK fighters by August 2015 in Turkey alone.[45][46][319][320] Among the civilian casualties, till 2012, 157 were teachers.[321] From August 1984 to June 2007, a total of 13,327 soldiers and 7,620 civilians were said to have been wounded.[55] About 2,500 people were said to have been killed between 1984 and 1991, while over 17,500 were killed between 1991 and 1995.[322] The number of murders committed by Village Guards from 1985 to 1996 is put at 296 by official estimates.[323]

Contrary to the newest estimate, earlier figures by the Turkish military put the number of PKK casualties much higher, with 26,128 PKK dead by June 2007,[55] and 29,704 by March 2009. Between the start of the second insurgency in 2004, and March 2009, 2,462 PKK militants were claimed killed.[193] However, later figures provided by the military for the 1984–2012 period, revised down the number of killed PKK members to 21,800.[324]

Both the PKK and Turkish military have accused each other of civilian deaths. Since the 1970s, the European Court of Human Rights has condemned Turkey for the thousands of human rights abuses against Kurdish people.[116][117] The judgments are related to systematic executions of Kurdish civilians,[118] torturing,[325] forced displacements,[326] thousands of destroyed villages,[121][122][123] arbitrary arrests,[124] murdered and disappeared Kurdish journalists, politicians and activists.[125] Turkey has been also condemned for killing Kurdish civilians and blaming the PKK in the ECHR (Kuskonar massacre).[118]

According to human rights organisations since the beginning of the uprising 4,000 villages have been destroyed,[327] in which between 380,000 and 1,000,000 Kurdish villagers have been forcibly evacuated from their homes, mainly by the Turkish military.[328] Some 5,000 Turks and 35,000 Kurds,[327] have been killed, 17,000 Kurds have disappeared and 119,000 Kurds have been imprisoned by Turkish authorities.[52][327] According to the Humanitarian Law Project, 2,400 Kurdish villages were destroyed and 18,000 Kurds were executed, by the Turkish government.[328] In total up to 3,000,000 people (mainly Kurds) have been displaced by the conflict,[56] an estimated 1,000,000 of which are still internally displaced as of 2009.[329] The Assyrian Minority was heavily affected as well, as now most (50–60 thousand/70,000) of its population is in refuge in Europe.

Sebahat Tuncel, an elected MP from the BDP, put the PKK's casualties at 18,000 as of July 2011.[330]

Before 2012 ceasefire

The Uppsala Conflict Data Program recorded 25,825–30,639 casualties to date, 22,729–25,984 of which having died during the first insurgency, 368–467 during the cease-fire and 2,728–4,188 during the second insurgency. Casualties from 1989 to 2011, according to the UCDP are as following:[194]

| Year | Low estimate | High estimate |

|---|---|---|

| 1989 | 227 | 234 |

| 1990 | 245 | 303 |

| 1991 | 304 | 310 |

| 1992 | 1,518 | 1,598 |

| 1993 | 2,099 | 2,394 |

| 1994 | 4,000 | 4,488 |

| 1995 | 3,076 | 3,951 |

| 1996 | 3,533 | 3,578 |

| 1997 | 4,247 | 5,483 |

| 1998 | 1,952 | 2,039 |

| 1999 | 1,403 | 1,481 |

| 2000 | 173 | 189 |

| 2001 | 81 | 96 |

| 2002 | 35 | 100 |

| 2003 | 79 | 82 |

| 2004 | 180 | 322 |

| 2005 | 324 | 611 |

| 2006 | 210 | 274 |

| 2007 | 458 | 509 |

| 2008 | 501 | 1,068 |

| 2009 | 128 | 149 |

| 2010 | 328 | 433 |

| 2011 | 599 | 822 |

| Total: | 25,825 | 30,639 |

The conflict's casualties between 1984 and March 2009 according to the General Staff of the Republic of Turkey, Turkish Gendarmerie, General Directorate of Security and since then until June 2010 according to Milliyet's analysis of the data of the General Staff of the Republic of Turkey and Turkish Gendarmerie were as following:[193]

| Year | Security forces | Civilians | Insurgents | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1984 | 26 | 43 | 28 | 97 |

| 1985 | 58 | 141 | 201 | 400 |

| 1986 | 51 | 133 | 74 | 258 |

| 1987 | 71 | 237 | 95 | 403 |

| 1988 | 54 | 109 | 123 | 286 |

| 1989 | 153 | 178 | 179 | 510 |

| 1990 | 161 | 204 | 368 | 733 |

| 1991 | 244 | 233 | 376 | 853 |

| 1992 | 629 | 832 | 1,129 | 2,590 |

| 1993 | 715 | 1,479 | 3,050 | 5,244 |

| 1994 | 1,145 | 992 | 2,510 | 4,647 |

| 1995 | 772 | 313 | 4,163 | 5,248 |

| 1996 | 608 | 170 | 3,789 | 4,567 |

| 1997 | 518 | 158 | 7,558 | 8,234 |

| 1998 | 383 | 85 | 2,556 | 3,024 |

| 1999 | 236 | 83 | 1,458 | 1,787 |

| 2000 | 29 | 17 | 319 | 365 |

| 2001 | 20 | 8 | 104 | 132 |

| 2002 | 7 | 7 | 19 | 33 |

| 2003 | 31 | 63 | 87 | 181 |

| 2004 | 75 | 28 | 122 | 225 |

| 2005 | 105 | 30 | 188 | 323 |

| 2006 | 111 | 38 | 132 | 281 |

| 2007 | 146 | 37 | 315 | 498 |

| 2008 | 171 | 51 | 696 | 918 |

| 2009 | 62 | 18 | 65 | 145 |

| 2010 | 72 | - | - | - |

| Total: | 6,653 | 5,687 | 29,704 | 42,044 |

Since 2013: from ceasefire to new confrontations

The Belgium-based Crisis Group keeps track of casualties linked to the Kuridsh–Turkish conflict.[331] This data is limited to proper Turkey, and does not include casualties from preemptive operations in Syria or Iraq.

| Year | Security forces | Civilians | Unknown youth | Insurgents | Total | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 14 | 21 | Ceasefire agreed by both Turkey (AKP) and PKK. |

| 2014* | 20 | 53 | 0 | 19 | 92 | |

| 2015, Jan. to June: ceasefire | 2 | 3 | 0 | 6 | 11 | |

| War resumed here due to June 2015's 2 security forces killed. | ||||||

| 2015, Jul. to Dec.: war | 206 | 128 | 87 | 261 | 682 | Ceasefire and peace process broke down on 20 July 2015. Military confrontation resumed. |

| 2015 | 208 | 131 | 87 | 267 | 693 | |

| 2016 | 645 | 269 | 136 | 1,162 | 2,212 | |

| 2017 | 164 | 50 | 0 | 591 | 805 | |

| 2018 | 123 | 17 | 0+ | 362 | 502+ | |

| 2019 Jan.-Sept. | 77 | 22 | 0 | 258 | 347 | |

| TOTAL | 1,240 | 544 | 223 | 2,573 | 4,672 | |

*: mainly due to the 6–8 October 2014 Kurdish riots where 42 civilians were killed by State Forces during anti-government protests by Kurdish groups throughout Turkey. The protesters denouncing Ankara position during Islamic State's siege of Kobani. This is the main incident out of the ceasefire period.[331]

The ceasefire agreement broke down in July 2015, dividing 2015 in two sharply different periods.

External operations

Turkey has led strikes and several ground operations in Syria and Iraq, in order to attack PKK-related groups.

| Date | Place | Type | Operation | Turkish forces dead (injured) | Turkish allies dead (injured) | Kurdish forces dead (captured) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 October – 15 November 1992 | Iraq | Operation Northern Iraq | 28 (125) | — | 1,551 (1,232) | |

| 20 March – 4 May 1995 | Iraq | Operation Steel* | 64 (185) | — | 555 (13) | |

| 12 May – 7 July 1997 | Iraq | Operation Hammer* | 114 (338) | — | 2,730 (415) | |

| 25 September – 15 October 1997 | Iraq | Operation Dawn* | 31 (91) | — | 865 (37) | |

| 21–29 February 2008 | Iraq | Operation Sun* | 27 | — | 240[332][333][334] | |

| 24–25 July 2015 | Iraq | Airstrikes | Operation Martyr Yalçın* | - | - | 160 |

| 24 August 2016 – 29 March 2017 | Syria | Land and air | Operation Euphrates Shield*,** | 71 | 614 | 131 (37) |

| 25 April 2017 | Syria, Iraq | Airstrikes | 2017 Turkish airstrikes in Syria and Iraq | 0 | — | 70 |

| 20 January – 24 March 2018 | Syria | Land and air | Operation Olive Branch* | 55 | 318 (Turkish claim) 2,541 (SDF claim) | 820 (SDF claim) 4,558 (Turkish claim) |

| 19 March 2018 – present | Iraq | Land and air | Operation Tigris Shield* | 112 (17) | — | 234[335][336] |

| 15 August 2018 | Sinjar, Iraq | Airstrikes | Turkish strikes on Sinjar (2018) | — | — | 5 |

| 28 May 2019 – present | Iraq | Airstrikes | Operation Claw (2019)* | — | — | 2 |

| 9 October 2019 – present | (Syria) | Land and air | Operation Peace Spring* | (ongoing) | (ongoing) | (ongoing) |

| 15 June 2020 | Iraq | Airstrikes | Operation Claw-Eagle (2020)* | — | — | ongoing |

| Total: | 502 (756) | 932–3,155 | 7,575–11,607 (1,737) | |||

*:these names by Turkey military or political leadership have communication / propaganda purposes

**: Most of Turkey's Operation Euphrates Shield combats were between TSK & TFSA against IS on one side, and between YPG against IS on the other, while the Turkish forces and US-allied YPG avoided full scale clashed. Turkey strategic objective was to prevent Afrin canton from connecting with YPG Manbij and other Rojava regions. Accordingly, only a minor part of these operations casualties were from Turkey forces vs YPG forces..

Demographic effect

The Turkification of predominantly Kurdish areas in country's East and South-East were also bound in the early ideas and policies of modern Turkish nationalism, going back to as early as 1918 to the manifesto of Turkish nationalist Ziya Gökalp "Turkification, Islamization and Modernization".[337] The evolving Young Turk conscience adopted a specific interpretation of progressism, a trend of thought which emphasizes the human ability to make, improve and reshape human society, relying of science, technology and experimentation.[338] This notion of social evolution was used to support and justify policies of population control.[338] The Kurdish rebellions provided a comfortable pretext for Turkish Kemalists to implement such ideas, and in a Settlement Law was issued in 1934. It created a complex pattern of interaction between state of society, in which the regime favored its people in a distant geography, populated by locals marked as hostile.[338]

During the 1990s, a predominantly Kurdish-dominated Eastern and South-Eastern Turkey (Kurdistan) was depopulated due to the Kurdish–Turkish conflict.[337] Turkey depopulated and destroyed rural settlements on a large scale, resulting in massive resettlement of a rural Kurdish population in urban areas and leading to development and re-design of population settlement schemes across the countryside.[337] According to Dr. Joost Jongerden, Turkish settlement and re-settlement policies during the 1990s period were influenced by two different forces – the desire to expand administration to rural areas and an alternative view of urbanization, allegedly producing "Turkishness".[337]

Human rights abuses

Both Turkey and the PKK have committed numerous human rights abuses during the conflict. Former French ambassador to Turkey Eric Rouleau states:[339]

According to the Ministry of Justice, in addition to the 35,000 people killed in military campaigns, 17,500 were assassinated between 1984, when the conflict began, and 1998. An additional 1,000 people were reportedly assassinated in the first nine months of 1999. According to the Turkish press, the authors of these crimes, none of whom have been arrested, belong to groups of mercenaries working either directly or indirectly for the security agencies.

Abuses by the Turkish side

Since the 1970s, the European Court of Human Rights has condemned Turkey for thousands of human rights abuses against Kurdish people.[116][117] The judgments are related to systematic executions of Kurdish civilians,[118] forced recruitments,[118] torturing,[325][119] forced displacements,[340] thousands of destroyed villages,[341] arbitrary arrests,[342] murdered and disappeared Kurdish journalists.[343] The latest judgments are from 2014.[118] According to David L. Philips, more than 1,500 people affiliated with the Kurdish opposition parties and organizations were murdered by unidentified assailants between 1986 and 1996. The government backed mercenaries assassinated hundreds of suspected PKK sympathizers.[156] The Turkish government is held responsible by Turkish human rights organizations for at least 3,438 civilian deaths in the conflict between 1987 and 2000.[344]

Massacres

In November 1992, the Turkish gendarmerie officers forced the leader of the Kelekçi village to evacuate all of the inhabitants, before shooting at them and their houses with heavy weapons. The soldiers set up fire to nine houses and forced all villagers to flee. Later soldiers burned the rest of the village and destroyed all 136 houses.[345]

In 1993, Mehmet Ogut, his pregnant wife and all their seven children were burned to death by Turkish special forces soldiers. The Turkish authorities initially blamed the PKK and refused to investigate the case until it was opened again 17 years later. The investigations eventually came to an end in late 2014 with sentences of life imprisonment for three gendarme officers, a member of the special forces and nine soldiers.[346]

On 8 September 1993, the Turkish Air Force dropped a bomb near the Munzur mountains, killing 2 women. In the same year, Turkish security forces attacked the town of Lice, destroying 401 houses, 242 shops and massacring more than thirty civilians, and leaving one hundred wounded.[347]

On 26 March 1994 the Turkish military planes (F-16's) and a helicopter circled two villages and bombed them, killing 38 Kurdish civilians.[118] The Turkish authorities blamed the PKK and took pictures of the dead children and spread in the press. The European Court of Human rights condemned Turkey to pay 2,3 million euros to the families of victims.[118] The event is known as the Kuşkonar massacre.

In 1995, Human Rights Watch reported that it was common practice for Turkish soldiers to kill Kurdish civilians and take pictures of their corpses with the weapons, they carried only for staging the events. Killed civilians were shown to press as PKK "terrorists".[348]

In 1995, The European newspaper published in its front-page pictures of Turkish soldiers who posed for camera with the decapitated heads of the Kurdish PKK fighters. Kurdish fighters were beheaded by Turkish special forces soldiers.[349][350]

In the late March 2006, the Turkish security forces who tried to prevent the funerals of the PKK fighters clashed with the demonstrators, killing at least eight Kurdish protesters, including four children under the age of 10.[351]

In August 2015, Amnesty International reported that the Turkish government airstrikes killed eight residents and injured at least eight others – including a child – in a flagrantly unlawful attack on the village of Zergele, in the Kandil Mountains in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq.[352]

On 21 January 2016, a report published by Amnesty International stated that more than 150 civilians had been killed in Cizre. According to Amnesty International, the curfews had been imposed in more than 19 different towns and districts, putting the lives of hundreds of thousands of people at risk. Additionally, the report stated that the government's disproportionate restrictions on movement and other arbitrary measures were resembling collective punishment, a war crime under the 1949 Geneva Conventions.[353][354]

Human Rights Watch notes in 1992 that:

- As Human Rights Watch has often reported and condemned, Turkish government forces have, during the conflict with the PKK, also committed serious violations of international human rights and humanitarian law, including torture, extrajudicial killings, and indiscriminate fire. We continue to demand that the Turkish government investigate and hold accountable those members of its security forces responsible for these violations. Nonetheless, under international law, the government abuses cannot under any circumstances be seen to justify or excuse those committed by Ocalan's PKK.[355]

- The Kurdish Workers Party (PKK), a separatist group that espouses the use of violence for political ends, continues to wage guerrilla warfare in the southeast, frequently in violation of international humanitarian law, or the laws of war. Instead of attempting to capture, question and indict people suspected of illegal activity, Turkish security forces killed suspects in house raids, thus acting as investigator, judge, jury and executioner. Police routinely asserted that such deaths occurred in shoot-outs between police and "terrorists". In many cases, eyewitnesses reported that no firing came from the attacked house or apartment. Reliable reports indicated that while the occupants of raided premises were shot and killed, no police were killed or wounded during the raids. This discrepancy suggests that the killings were summary, extrajudicial executions, in violation of international human rights and humanitarian law.[356]

Turkish–Kurdish human right activists in Germany accused Turkey of using chemical weapons against PKK. Hans Baumann, a German expert on photo forgeries, investigated the authenticity of the photos and claimed that the photos were authentic. A forensics report released by the Hamburg University Hospital has backed the allegations. Claudia Roth from Germany's Green Party demanded an explanation from the Turkish government.[357] The Turkish Foreign Ministry spokesman Selçuk Ünal commented on the issue. He said that he did not need to emphasize that the accusations were groundless. He added that Turkey signed to the Chemical Weapons Convention in 1997, and Turkey did not possess chemical weapons.[358] Turkey has been a signatory to the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on their Destruction since 1997, and has passed all inspections required by such convention.[359]

In response to the activities of the PKK, the Turkish government placed Southeastern Anatolia, where citizens of Kurdish descent are in the majority, under military rule. The Turkish Army and the Kurdish village guards loyal to it have abused Kurdish civilians, resulting in mass migrations to cities.[85] The Government claimed that the displacement policy aimed to remove the shelter and support of the local population and consequently, the population of cities such as Diyarbakır and Cizre more than doubled.[360] However, martial law and military rule was lifted in the last provinces in 2002.

State terrorism

Since its foundation, the Republic of Turkey has pursued variously assimilationist and repressive policies towards the Kurdish people.[361] At the beginning of the conflict, the PKK's relationship with its civilian supporters created incentives for the Turkish government to use terrorism against the Kurdish citizens in the Kurdish dominated southeast region of Turkey.[160] Since the early 1980s, the authorities have systematically used arbitrary arrests, executions of suspects, excessive force, and torture to suppress the opponents. In 1993, the report published by Human Rights Watch stated:[362]

Kurds in Turkey have been killed, tortured and disappeared at an appalling rate since the coalition government of Prime Minister Suleyman Demirel took office in November 1991. In addition, many of their cities have been brutally attacked by security forces, hundreds of their villages have been forcibly evacuated, their ethnic identity continues to be attacked, their rights to free expression denied and their political freedom placed in jeopardy.

According to Human Rights Watch, the authorities even executed the Kurdish civilians and took the pictures of their corpses with the weapons, they carried for staging the events, in order to show them as Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) "terrorists" to press. In 1995, another report published by Human Rights Watch stated:[363]

Based on B.G.'s statement and substantial additional evidence, Human Rights Watch believes that the official government casualty estimates severely misrepresent the true number of civilians slain by government forces. It is likely that many of the persons referred to in the official estimates as "PKK casualties" were in fact civilians shot by mistake or deliberately killed by security forces. Witness testimony also demonstrates that many of the Turkish government's denials of wrong-doing by the Turkish security forces are fabrications manufactured by soldiers or officials somewhere along the government's chain of command.

Shooting and killing peaceful demonstrators was one of the methods the security forces used to spread fear. In 1992, the security forces killed more than 103 demonstrators, 93 of them during the celebration of Newroz in three Kurdish cities. No security force member was ever charged with any of the deaths.[362]

In the early 1990s, hundreds of people had disappeared after they had been taken into custody by security forces. Only in 1992, more than 450 people had been reportedly killed. Among those killed were journalists, teachers, doctors, human rights activists and political leaders. The security forces usually denied to have detained the victims but sometimes they claimed that they had released the victims after "holding them briefly".[362] According to the Human Rights Association (İHD), there have been 940 cases of enforced disappearance since the 1990s. In addition to that, more than 3,248 people who were murdered in extrajudicial killings are believed to have been buried in 253 separate burial places. On 6 January 2011, the bodies of 12 people were found in a mass grave near an old police station in Mutki, Bitlis. A few months later, three other mass graves were reportedly found in the garden of Çemişgezek police station.[364][365][366]

In 2006, the former ambassador Rouleau stated that the continuing human rights abuses of ethnic Kurds is one of the main obstacles to Turkish membership of the EU[367]

Illegal abductions and enforced disappearances

During the 1990s and onward Turkish security services have detained Kurds, in some cases they were never seen again with only eyewitnesses coming forward to tell the story.[368] In 1997, Amnesty International (AI) reported that disappearances and extrajudicial executions had emerged as new and disturbing patterns of human rights violations by the Turkish state.[369][370]

The Stockholm Center for Freedom (SCF) documented eleven cases since 2016 in which people have been abducted by men identifying themselves as police officers. It appears to be mostly in the Turkish capital of Ankara as victims are forced into transit vans. Family members unable to find out their locations from the state, indicating that they are detained secretly or by clandestine groups. In a case where one was finally located after 42 days missing, he was tortured for days, forced to sign a confession and handed over to police.[371]

Torture

In August 1992, Human Rights Watch reported the vile practice of torture by security forces in Turkey. The victims of torture interviewed by Helsinki Watch had revealed the systematic practice of torture against detainees in police custody. Sixteen people had died in suspicious circumstances in police custody, ten of them Kurds in the Southeast.[362]

In 2013, The Guardian reported that the rape and torture of Kurdish prisoners in Turkey are disturbingly commonplace. According to the report, published by Amnesty International in 2003, Hamdiye Aslan, a prisoner accused of supporting the Kurdish group, the PKK, had been detained in Mardin Prison, south-east Turkey, for almost three months in which she was reportedly blindfolded, anally raped with a truncheon, threatened and mocked by officers.[372]

In February 2017, a report published by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights stated the Turkish authorities had beaten and punched detainees, using sexual violence, including rape and threat of rape. In some cases, the detainees were photographed nude and threatened with public humiliation after being tortured by Turkish authorities.[373]

Executions

On 24 February 1992, Cengiz Altun, the Batman correspondent for the weekly pro-Kurdish newspaper, Yeni Ülke, was killed.[374] More than 33 Kurdish journalists working for different newspapers were killed between 1990 and 1995. The killings of Kurdish journalists had started after the pro-Kurdish press had started to publish the first daily newspaper by the name of "Özgür Gündem" (Free Agenda). Musa Anter, a prominent Kurdish intellectual and journalist of Özgur Gundem, was assassinated by members of Gendarmerie Intelligence Organization in 1992.

In 1992, Turkish security forces executed seventy-four people in house raids and more than hundred people in demonstrations.[362]

In October 2016, amateur footage emerged showing Turkish soldiers executing two female PKK members they had captured alive.[375]

In February 2017, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights published a report condemning the Turkish government for carrying out systematic executions, displacing civilians, and raping and torturing detainees in Southeastern Turkey.[373]

In October 2019, nine people were executed, including Hevrin Khalaf, a 35-year-old Kurdish woman who was secretary-general of the Future Syria Party and who worked for interfaith unity.[376]

Arrests

Since the early 1980s, the Turkish government has been responsible for hundreds of thousands arrests and detentions.

Abuses by the Kurdish side

%2C_Eyl%C3%BCl_2015.jpg)