International waters

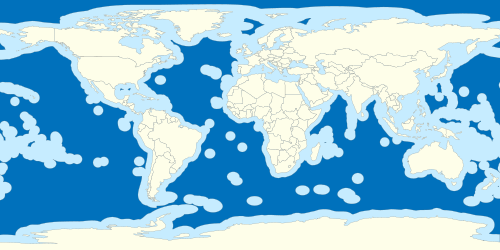

The terms international waters or trans-boundary waters apply where any of the following types of bodies of water (or their drainage basins) transcend international boundaries: oceans, large marine ecosystems, enclosed or semi-enclosed regional seas and estuaries, rivers, lakes, groundwater systems (aquifers), and wetlands.[1]

|

“International waters” is not a defined term in international law. It is an informal term, which most often refers to waters beyond the "territorial sea" of any state.[2] In other words, "international waters" is often used as an informal synonym for the more formal term high seas or, in Latin, mare liberum (meaning free sea).

International waters (high seas) do not belong to any State's jurisdiction, known under the doctrine of 'Mare liberum'. States have the right to fishing, navigation, overflight, laying cables and pipelines, as well as scientific research.

The Convention on the High Seas, signed in 1958, which has 63 signatories, defined "high seas" to mean "all parts of the sea that are not included in the territorial sea or in the internal waters of a State" and where "no State may validly purport to subject any part of them to its sovereignty."[3] The Convention on the High Seas was used as a foundation for the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), signed in 1982, which recognized Exclusive Economic Zones extending 200 nautical miles (230 mi; 370 km) from the baseline, where coastal States have sovereign rights to the water column and sea floor as well as the natural resources found there.[4]

The high seas make up 50% of the surface area of the planet and cover over two-thirds of the ocean.[5]

Ships sailing the high seas are generally under the jurisdiction of the flag state (if there is one);[6] however, when a ship is involved in certain criminal acts, such as piracy,[7] any nation can exercise jurisdiction under the doctrine of universal jurisdiction. International waters can be contrasted with internal waters, territorial waters and exclusive economic zones.

UNCLOS also contains, in its part XII, special provisions for the protection of the marine environment, which, in certain cases, allow port States to exercise extraterritorial jurisdiction over foreign ships on the high seas if they violate international environmental rules (adopted by the IMO), such as the MARPOL Convention.[8]

International waterways

Several international treaties have established freedom of navigation on semi-enclosed seas.

- The Copenhagen Convention of 1857 opened access to the Baltic by abolishing the Sound Dues and making the Danish Straits an international waterway free to all commercial and military shipping.

- Several conventions have opened the Bosphorus and Dardanelles to shipping. The latest, the Montreux Convention Regarding the Regime of the Turkish Straits, maintains the straits' status as an international waterway.

Other international treaties have opened up rivers, which are not traditionally international waterways.

Disputes over international waters

Current unresolved disputes over whether particular waters are "International waters" include:

- The Arctic Ocean: While Canada, Denmark, Russia and Norway all regard parts of the Arctic seas as national waters or internal waters, most European Union countries and the United States officially regard the whole region as international waters. The Northwest Passage through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago is one of the more prominent examples, with Canada claiming it as internal waters, while the United States and the European Union considers it an international strait.[9]

- The Southern Ocean: Australia claims an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) around its Antarctic territorial claim. Since this claim is only recognised by four other countries, the EEZ claim is also disputed.

- Area around Okinotorishima: Japan claims Okinotorishima is an islet and thus they should have an EEZ around it, but some neighboring countries claim it is an atoll and thus should not have an EEZ.

- South China Sea: See Territorial disputes in the South China Sea. Some countries[note 1] consider (at least part of) the South China Sea as international waters, but this viewpoint is not universal. Notably, China, which opposes any suggestion that coastal States could be obliged to share the resources of the exclusive economic zone with other powers that had historically fished there, claims historical rights to the resources of the exclusive economic zones of all other coastal States in the South China Sea.[10]

In addition to formal disputes, the government of Somalia exercises little control de facto over Somali territorial waters. Consequently, much piracy, illegal dumping of waste and fishing without permit has occurred.

Although water is often seen as a source of conflict, recent research suggests that water management can be a source for cooperation between countries. Such cooperation will benefit participating countries by being the catalyst for larger socio-economic development.[11] For instance, the countries of the Senegal River Basin that cooperate through the Organisation pour la Mise en Valeur du Fleuve Sénégal (OMVS) have achieved greater socio-economic development and overcome challenges relating to agriculture and other issues.[12]

International waters agreements

| Outer space (including Earth orbits; the Moon and other celestial bodies, and their orbits) | |||||||

| national airspace | territorial waters airspace | contiguous zone airspace | international airspace | ||||

| land territory surface | internal waters surface | territorial waters surface | contiguous zone surface | Exclusive Economic Zone surface | international waters surface[note 2] | ||

| internal waters | territorial waters | exclusive economic zone | international waters[note 2] | ||||

| land territory underground | Continental Shelf surface | extended continental shelf surface | international seabed surface | ||||

| Continental Shelf underground | extended continental shelf underground | international seabed underground | |||||

Global agreements

- International Freshwater Treaties Database (freshwater only).[13]

- The Yearbook of International Cooperation on Environment and Development profiles agreements regarding the Marine Environment, Marine Living Resources and Freshwater Resources.[14]

- 1972 London Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter (London Convention 1972).[15]

- 1973 London International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, 1973 MARPOL

- 1982 United Nations Convention on Law of the Sea (United Nations Convention on Law of the Sea, United Nations; especially parts XII–XIV).[16]

- 1997 United Nations Convention on the Law of Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses (CIW) – not ratified.[17]

- Transboundary Groundwater Treaty, Bellagio Draft – proposed, but not signed.[18]

- Other global conventions and treaties with implications for International Waters:

- 1971 Ramsar Convention on Wetlands.[19]

- 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity.[20]

Regional agreements

At least ten conventions are included within the Regional Seas Program of UNEP,[21] including:

- the Atlantic Coast of West and Central Africa[22]

- the North-East Pacific (Antigua Convention)

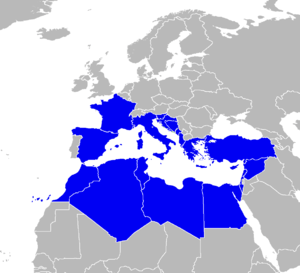

- the Mediterranean (Barcelona Convention)

- the wider Caribbean (Cartagena Convention)

- the South-East Pacific[23]

- the South Pacific (Nouméa Convention)

- the East African seaboard[24]

- the Kuwait region (Kuwait Convention)

- the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden (Jeddah Convention)

Addressing regional freshwater issues is the 1992 Helsinki Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes (UNECE/Helsinki Water Convention)[25]

Water-body-specific agreements

- Baltic Sea (Helsinki Convention on the Protection of the Marine Environment of the Baltic Sea Area, 1992)[26]

- Black Sea (Bucharest Convention)[27]

- Caspian Sea (Framework Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the Caspian Sea)[28]

- Lake Tanganyika (Convention for the Sustainable Management of Lake Tanganyika)[29]

International waters institutions

Freshwater institutions

- The UNESCO International Hydrological Programme (IHP)

- The International Joint Commission between Canada and United States (IJC-CMI)

- The International Network of Basin Organizations (INBO)

- The International Shared Aquifer Resource Management project

- The International Water Boundary Commission (US Section) between Mexico and United States

- The International Water Management Institute (IWMI)

- The IUCN Water and Nature Initiative (WANI)

Marine institutions

- The International Maritime Organization (IMO)

- The International Seabed Authority

- The International Whaling Commission

- The UNEP Regional Seas Programme

- The UNESCO Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC)

- The International Ocean Institute

- The IUCN Global Marine and Polar Programme (GMPP)

See also

Explanatory notes

- Including Japan, India, the United States, an arbitral tribunal constituted under Annex VII to the 1982 United Nations Convention on Law of the Sea, and the People's Republic of China, which opposed any suggestion that coastal States could be obliged to share the resources of the exclusive economic zone with other powers that had historically fished in those waters during the Third Conference of the United Nations on the Law of the Seas.

- The term "international waters" technically includes the "Contiguous Zone" and "Exclusive Economic Zone," although the chart only uses this term where no national jurisdiction or special rights apply.

Citations

- International Waters Archived 27 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine, United Nations Development Programme

- Buchanan, Michael. "Who's in charge here?". ShareAmerica. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- Text of CONVENTION ON THE HIGH SEAS (U.N.T.S. No. 6465, vol. 450, pp. 82–103)

- "What is the EEZ". National Ocean Service. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- "THE HIGH SEAS". Ocean Unite. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- UNCLOS article 92(1)

- UNCLOS article 105

- Jesper Jarl Fanø (2019). Enforcing International Maritime Legislation on Air Pollution through UNCLOS. Hart Publishing.

- Carnaghan, Matthew; Goody, Allison (26 January 2006), Canadian Arctic Sovereignty, Library of Parliament, retrieved 16 December 2016

- 李侠. "学者:南海不存在公海 他国不能横行霸道_历史_环球网". Archived from the original on 22 April 2017. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- Waslekar, Selim Catafago, Fadi Comair, Paul Salem, Sundeep. "The Blue Peace: Rethinking Middle East Water". Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- http://strategicforesight.com/publication_pdf/20795water-cooperature-sm.pdf

- "International Freshwater Treaties Database". Transboundarywaters.orst.edu. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- "Yearbook of International Cooperation on Environment and Development". Archived from the original on 12 February 2009.

Marine Environment

Marine Living Resources

Freshwater Resources - "International Maritime Organization". Archived from the original on 26 October 2008. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- "United Nations Convention on Law of the Sea". Un.org. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- "CIW" (PDF). Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- "Bellagio Draft" (PDF). Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- "Text of Ramsar Convention and other key original documents". Ramsar.org. Archived from the original on 4 November 2011. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- Text of the Convention on Biological Diversity especially Articles 12–13, as related to transboundary aquatic ecosystems

- "Regional Seas Program". Unep.org. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- "Convention for Co-operation in the Protection and Development of the Marine and Coastal Environment of the West and Central African Region; and Protocol (1981)". Sedac.ciesin.org. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- Lima Convention, 1986)

- Nairobi Convention, 1985);

- "Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes". Unece.org. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- "Convention on the Protection of the Marine Environment of the Baltic Sea Area". Helcom.fi. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- "Commission on the Protection of the Black Sea Against Pollution". Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- Framework Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the Caspian Sea, 2003

- Convention for the Sustainable Management of Lake Tanganyika, 2003

External links

- Bibliography on Water Resources and International Law Peace Palace Library

- The GEF International Waters Resource Centre (GEF IWRC)

- The Integrated Management of Transboundary Waters in Europe (TransCat)

- The International Water Law Project

- The International Water Resources Association (IWRA)

- Food and Agriculture Organization

- Ocean Atlas

- Transboundary Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) article

- OneFish fisheries research portal

- Regional Fisheries Bodies of the World portal

- The UNDP-GEF article describing international waters from which this article has been adapted.

- UNEP freshwater thematic portal on transboundary waters

- UNESCO thematic portals for oceans, water, coasts and small islands

- WaterWiki: A new Wiki-based on-line knowledge map and collaboration tool for Water-practitioners in the Europe & CIS region