Military camouflage

Military camouflage is the use of camouflage by an armed force to protect personnel and equipment from observation by enemy forces. In practice, this means applying colour and materials to military equipment of all kinds, including vehicles, ships, aircraft, gun positions and battledress, either to conceal it from observation (crypsis), or to make it appear as something else (mimicry). The French slang word camouflage came into common English usage during World War I when the concept of visual deception developed into an essential part of modern military tactics. In that war, long-range artillery and observation from the air combined to expand the field of fire, and camouflage was widely used to decrease the danger of being targeted or to enable surprise. As such, military camouflage is a form of military deception.

| Part of a series on |

| War |

|---|

|

|

|

Related

|

Camouflage was first practiced in simple form in the mid 18th century by rifle units. Their tasks required them to be inconspicuous, and they were issued green and later other drab colour uniforms. With the advent of longer range and more accurate weapons, especially the repeating rifle, camouflage was adopted for the uniforms of all armies, spreading to most forms of military equipment including ships and aircraft. Many modern camouflage textiles address visibility not only to visible light but also near infrared, for concealment from night vision devices. Camouflage is not only visual; heat, sound, magnetism and even smell can be used to target weapons, and may be intentionally concealed. Some forms of camouflage have elements of scale invariance, designed to disrupt outlines at different distances, typically digital camouflage patterns made of pixels. Camouflage patterns also have cultural functions such as political identification.

Camouflage for equipment and positions was extensively developed for military use by the French in 1915, soon followed by other World War I armies. In both world wars, artists were recruited as camouflage officers. Ship camouflage developed via conspicuous dazzle camouflage schemes during WWI, but since the development of radar, ship camouflage has received less attention. Aircraft, especially in World War II, were often countershaded: painted with different schemes above and below, to camouflage them against the ground and sky respectively.

Military camouflage patterns have been popular in fashion and art from as early as 1915. Camouflage patterns have appeared in the work of artists such as Andy Warhol and Ian Hamilton Finlay, sometimes with an anti-war message. In fashion, many major designers have exploited camouflage's style and symbolism, and military clothing or imitations of it have been used both as street wear and as a symbol of political protest.

Principles

Military camouflage is part of the art of military deception. The main objective of military camouflage is to deceive the enemy as to the presence, position and intentions of military formations. Camouflage techniques include concealment, disguise, and dummies, applied to troops, vehicles, and positions.[1]

Vision is the main sense of orientation in humans, and the primary function of camouflage is to deceive the human eye. Camouflage works through concealment (whether by countershading, preventing casting shadows, or disruption of outlines), mimicry, or possibly by dazzle.[2][3] In modern warfare, some forms of camouflage, for example face paints, also offer concealment from infrared sensors, while CADPAT textiles in addition help to provide concealment from radar.[4][5]

Compromises

While camouflage tricks are in principle limitless, both cost and practical considerations limit the choice of methods and the time and effort devoted to camouflage. Paint and uniforms must also protect vehicles and soldiers from the elements. Units need to move, fire their weapons and perform other tasks to keep functional, some of which run counter to camouflage.[2] Camouflage may be dropped altogether. Late in the Second World War, the USAAF abandoned camouflage paint for some aircraft to lure enemy fighters to attack, while in the Cold War, some aircraft similarly flew with polished metal skins, to reduce drag and weight, or to reduce vulnerability to radiation from nuclear weapons.[6]

No single camouflage pattern is effective in all terrains.[7] The effectiveness of a pattern depends on contrast as well as colour tones. Strong contrasts which disrupt outlines are better suited for environments such as forests where the play of light and shade is prominent, while low contrasts are better suited to open terrain with little shading structure.[8] Terrain-specific camouflage patterns, made to match the local terrain, may be more effective in that terrain than more general patterns. However, unlike an animal or a civilian hunter, military units may need to cross several terrain types like woodland, farmland and built up areas in a single day.[2] While civilian hunting clothing may have almost photo-realistic depictions of tree bark or leaves (indeed, some such patterns are based on photographs),[9] military camouflage is designed to work in a range of environments. With the cost of uniforms in particular being substantial, most armies operating globally have two separate full uniforms, one for woodland/jungle and one for desert and other dry terrain.[2] An American attempt at a global camouflage pattern for all environments (the 2004 UCP) was however withdrawn after a few years of service.[10] On the other end of the scale are terrain specific patterns like the "Berlin camo", applied to British vehicles operating in Berlin during the Cold War, where square fields of various gray shades was designed to hide vehicles against the mostly concrete architecture of post-war Berlin.[11]

Other functions

.jpg)

Camouflage patterns serve cultural functions alongside concealment. Apart from concealment, uniforms are also the primary means for soldiers to tell friends and enemies apart. The camouflage experts and evolutionary zoologists L. Talas, R. J. Baddeley and Innes Cuthill analyzed calibrated photographs of a series of NATO and Warsaw Pact uniform patterns and demonstrated that their evolution did not serve any known principles of military camouflage intended to provide concealment. Instead, when the Warsaw Pact was dissolved, the uniforms of the countries that began to favour the West politically started to converge on the colours and textures of NATO patterns. After the death of Marshal Tito and the breakup of what had been Yugoslavia, the camouflage patterns of the new nations changed, coming to resemble the camouflage patterns used by the armies of their neighbours. The authors note that military camouflage resembles animal coloration in having multiple simultaneous functions.[12]

Snow camouflage

Seasons may play a role in some regions. A dramatic change in colour and texture is created by seasonal snowy conditions in northern latitudes, necessitating repainting of vehicles and separate snow oversuits. The Eastern and northern European countries have a tradition for separate winter uniforms rather than oversuits.[2] During the Second World War, the Waffen-SS went a step further, developing reversible uniforms with separate schemes for summer and autumn, as well as white winter oversuits.[13]

Movement

While patterns can provide more effective crypsis than solid colour when the camouflaged object is stationary, any pattern, particularly one with high contrast, stands out when the object is moving.[14][15] Jungle camouflage uniforms were issued during the Second World War, but both the British and American forces found that a simple green uniform provided better camouflage when soldiers were moving. After the war, most nations returned to a unicoloured uniform for their troops.[2] Some nations, notably Austria and Israel, continue to use solid colour combat uniforms today.[16][17] Similarly, while larger military aircraft traditionally had a disruptive pattern with a darker top over a lighter lower surface (a form of countershading), modern fast fighter aircraft often wear gray overall.[6]

Digital camouflage

.jpg)

Digital camouflage provides a disruptive effect through the use of pixellated patterns at a range of scales, meaning that the camouflage helps to defeat observation at a range of distances.[18] Such patterns were first developed during the Second World War, when Johann Georg Otto Schick designed a number of patterns for the Waffen-SS, combining micro- and macro-patterns in one scheme.[13] The German Army developed the idea further in the 1970s into Flecktarn, which combines smaller shapes with dithering; this softens the edges of the large scale pattern, making the underlying objects harder to discern.Pixellated shapes pre-date computer aided design by many years, already being used in Soviet Union experiments with camouflage patterns, such as "TTsMKK"[lower-alpha 1] developed in 1944 or 1945.[19]

In the 1970s, US Army officer Timothy R. O'Neill suggested that patterns consisting of square blocks of colour would provide effective camouflage. By 2000, O'Neill's idea was combined with patterns like the German Flecktarn to create pixellated patterns such as CADPAT and MARPAT.[20] Battledress in digital camouflage patterns was first designed by the Canadian Forces. The "digital" refers to the coordinates of the pattern, which are digitally defined.[21] The term is also used of computer generated patterns like the non-pixellated Multicam and the Italian fractal Vegetato pattern.[22] Pixellation does not in itself contribute to the camouflaging effect. The pixellated style, however, simplifies design and eases printing on fabric.[23]

Non-visual

With the birth of radar and sonar and other means of detecting military hardware not depending on the human eye, came means of camouflaging against them. Collectively these are known as stealth technology.[24] Aircraft and ships can be shaped to reflect radar impulses away from the sender, and covered with radar-absorbing materials, to reduce their radar signature.[24][25] The use of heat-seeking missiles has also led to efforts to hide the heat signature of aircraft engines. Methods include exhaust ports shaped to mix hot exhaust gases with cold surrounding air,[26] and placing the exhaust ports on the upper side of the airframe.[27] Multi-spectral camouflage attempts to hide objects from detection methods such as infra-red, radar, and millimetre-wave imaging simultaneously.[28]

Auditory camouflage, at least in the form of noise reduction, is practised in various ways. The rubberized hull of military submarines absorbs sonar waves and can be seen as a form of auditory camouflage.[29] Some modern helicopters are designed to be quiet.[30] Combat uniforms are usually equipped with buttons rather than snap fasteners or velcro to reduce noise.[2]

Olfactory camouflage is said to be rare;[31] examples include ghillie suits, special garments for military snipers made from strips of hessian cloth, which are sometimes treated with mud and even manure to give them an "earthy" smell to cover the smell of the sniper.[32]

Magnetic camouflage in the form of "degaussing" coils has been used since the Second World War[33] to protect ships from magnetic mines and other weapons with magnetic sensors. Horizontal coils around the whole or parts of the ship generate magnetic fields to "cancel out" distortions to the earth's magnetic field created by the ship.[34]

History

Reconnaissance and riflemen

Ship camouflage was occasionally used in ancient times. Vegetius wrote in the 4th century that "Venetian blue" (bluish-green, like the sea) was used for camouflage in the years 56–54 BC during the Gallic Wars, when Julius Caesar sent his scout ships to gather intelligence along the coast of Britain. The bluish-green scout ships carried sailors and marines dressed in the same colour.[35][36][37][38]

The emphasis on hand-to-hand combat, and the short range of weapons such as the musket, meant that recognition and cohesion were more important than camouflage in combat clothing well into the baroque period. The introduction of infantry weapons with longer range, especially the Baker rifle, opened up new roles which needed camouflaged clothing. In the colonial Seven Years' War (1756–1763), the rifle-armed Rogers' Rangers wore gray or green uniforms.[39] John Graves Simcoe, one of the unit's later commanders, noted in 1784:[40]

Green is without comparison the best colour for light troops with dark accouterments; and if put on in the spring, by autumn it nearly fades with the leaves, preserving its characteristic of being scarcely discernible at a distance.

The tradition was continued by British Rifle Regiments who adopted rifle green for the Napoleonic Wars.[41]

During the Peninsular War, Portugal fielded light infantry units known as Caçadores, who wore brown-jackets which helped conceal them. The brown color was considered to be more adequate for a concealment in the landscape of most of Portuguese regions, in general more arid than the greener landscapes of Central and Northern Europe.[42]

The first introduction of drab general uniform was by the British Corps of Guides in India in 1848.[43] Initially the drab uniform was specially imported from England, with one of the reasons being to "make them invisible in a land of dust".[44] However, when a larger quantity was required the army improvised, using a local dye to produce uniform locally. This type of drab uniform soon became known as khaki (Urdu for dusty, soil-coloured) by the Indian soldiers, and was of a similar colour to a local dress of cotton coloured with the mazari palm.[45] The example was followed by other British units during the mutiny of 1857, dying their white drill uniforms to inconspicuous tones with mud, tea, coffee or coloured inks. The resulting hue varied from dark or slate grey through light brown to off-white, or sometimes even lavender. This improvised measure gradually became widespread among the troops stationed in India and North-West Frontier, and sometimes among the troops campaigning on the African continent.[46]

Rifle fire

While long range rifles became the standard weapon in the 1830s, armies were slow to adapt their tactics and uniforms, perhaps as a result of mainly fighting colonial wars against less well armed opponents. Not until the First Boer War of 1880/81 did a major European power meet an opponent well equipped with and well versed in the use of modern long range repeating firearms, forcing an immediate change in tactics and uniforms.[47] Khaki-coloured uniform became standard service dress for both British and British Indian Army troops stationed in British India in 1885, and in 1896 khaki drill uniform was adopted by British Army for the service outside of Europe in general, but not until the Second Boer War, in 1902, did the entire British Army standardise on khaki (officially known as "drab") for Service Dress.[48][49]

The US military, who had blue-jacketed rifle units in the Civil War, were quick to follow the British, going khaki in the same year. Russia followed, partially, in 1908. The Italian Army used grigio-verde ("grey-green") in the Alps from 1906 and across the army from 1909. The Germans adopted feldgrau ("field grey") in 1910. By the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, France was the only major power to still field soldiers dressed in traditional conspicuous uniforms.[50]

The First World War

The First World War was the first full scale industrial conflict fought with modern firearms. The first attempt at disruptive camouflaged garment for the French army was proposed in 1914 by the painter Louis Guingot, but was refused by the army, which nevertheless kept a sample of the clothing. In collaboration with a Russian chemist friend, Guingot had developed a process of painting on weather-resistant fabric before the war and had registered a patent for it.[51] But the casualty rate on the Western Front forced the French to finally relinquish their blue coats and red trousers, adopting a grayish "horizon blue" uniform.[52]

The use of rapid firing machine guns and long range breech loading artillery quickly led to camouflaging of vehicles and positions.[53] Artillery pieces were soon painted in contrasting bold colours to obscure their outlines. Another early trend was building observation trees, made of steel with bark camouflage. Such trees became popular with the British and French armies in 1916.[54] The observation tree was invented by French painter Lucien-Victor Guirand de Scévola, who led the French army's camouflage unit, the first of its kind in any army.[55] He also invented painted canvas netting to hide machine gun positions, and this was quickly taken up for hiding equipment and gun positions from 1917, 7 million square yards being used by the end of the war.[56]

The First World War also saw the birth of aerial warfare, and with it the need not only to conceal positions and vehicles from being spotted from the air, but also the need to camouflage the aircraft themselves. In 1917, Germany started using a lozenge camouflage covering Central Powers aircraft, possibly the earliest printed camouflage.[57] A similarly disruptive splinter pattern in earth tones, Buntfarbenanstrich 1918, was introduced for tanks in 1918, and was also used on the Stahlhelm (steel helmet), becoming the first use of a standardized camouflage pattern for soldiers.[58]

Camoufleurs

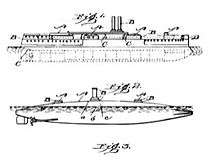

In 1909 an American artist and amateur zoologist, Abbott Thayer published a book, Concealing-Coloration in the Animal Kingdom, which was widely read by military leaders, though his advocacy of countershading was unsuccessful, despite his patent for countershading submarines and surface ships.[59]

The earliest camouflage artists were members of the Post- Impressionist and Fauve schools of France. Contemporary artistic movements such as cubism, vorticism and impressionism also influenced the development of camouflage as they dealt with disrupting outlines, abstraction and colour theory.[60][61]The French established a Section de Camouflage (Camouflage Department) at Amiens in 1915, headed by Lucien-Victor Guirand de Scévola.[55] His camoufleurs included the artists Jacques Villon, André Dunoyer de Segonzac, Charles Camoin and André Mare.[62][63]

Camouflage schemes of the First World War and Interwar periods that employed dazzle patterns were often described as "cubist" by commentators, and Picasso claimed with typical hyperbole "Yes, it is we who made it, that is cubism".[63] Most of the artists employed as camoufleurs were traditional representative painters, not cubists, but de Scévola claimed "In order to deform totally the aspect of the object, I had to employ the means that cubists use to represent it."[64]

Other countries soon saw the advantage of camouflage, and established their own units of artists, designers and architects. The British established a Camouflage Section in late 1916 at Wimereux,[65] and the U.S. followed suit with the New York Camouflage Society in April 1917, the official Company A of 40th Engineers in January 1918 and the Women's Reserve Camouflage Corps. The Italians set up the Laboratorio di mascheramento in 1917. By 1918 de Scévola was in command of camouflage workshops with over 9,000 workers, not counting the camoufleurs working at the front itself.[66] Norman Wilkinson who first proposed dazzle camouflage to the British military employed 5 male designers and 11 women artists, who by the end of the war had painted more than 2,300 vessels.[67] French women were employed behind the lines of both the British and American armies, sewing netting to disguise equipment and designing apparel for soldiers to wear.[68][69]

From the Second World War

Printed camouflage for shelter halves was introduced for the Italian and German armies in the interwar period, the "splotchy" M1929 Telo mimetico in Italy and the angular Splittermuster 31 in Germany. During the War, both patterns were used for paratrooper uniforms for their respective countries.[70] The British soon followed suit with a brush-stroke type pattern for their paratrooper's Denison smock, and the Soviets introduced an "amoeba" pattern overgarment for their snipers.[71]

Hugh Cott's 1940 book Adaptive Coloration in Animals systematically covered the different forms of camouflage and mimicry by which animals protect themselves, and explicitly drew comparisons throughout with military camouflage:[72]

The principle is one with many applications to modern warfare. In the Great War it was utilized by the Germans when they introduced strongly marked incidents of white or black tone to conceal the fainter contrasts of tone made by the sloping sides of overhead camouflage-screens, or roofing, as seen from the air. The same principle has, of course, a special application in any attempt to reduce the visibility of large objects of all kinds, such as ships, tanks, buildings, and aerodromes.

— Hugh Cott[72]

Both British and Soviet aircraft were given wave-type camouflage paintwork for their upper surfaces throughout the war,[73] while American ones remained simple two-colour schemes (different upper and under sides) or even dispensed with camouflage altogether.[74] Italian and some Japanese aircraft wore sprayed-on spotted patterns.[75][76] German aircraft mostly used an angular splint-pattern camouflage, but Germany experimented with different schemes, particularly in the later stages of the war.[77] They also experimented with various spray-on camouflage patterns for tanks and other vehicles, while Allied vehicles remained largely uni-coloured.[78] As they had volunteered in the first World War, women sewed camouflage netting, organizing formalized groups for the work in Australia, Britain, New Zealand and the United States who took part as camoufleurs during the second war.[79][80][81][82]

The British Middle East Command Camouflage Directorate, consisting mainly of artists recruited into the Royal Engineers, developed the use of camouflage for large-scale military deception.[83] Operations combined the disguise of actual installations, vehicles and stores with the simultaneous display of dummies, whether to draw fire or to give a false idea of the strength of forces or likely attack directions.[83] In Operation Bertram for the decisive battle at El Alamein, a whole dummy armoured division was constructed, while real tanks were disguised as soft-skinned transport using "Sunshield" covers.[83][84] The capabilities so developed were put to use not only in the western desert, but also in Europe as in the Operation Bodyguard deception for the Invasion of Normandy,[83] and in the Pacific campaign, as in the Battle of Goodenough Island.[85]

The introduction of strategic bombing led to efforts to camouflage airfields and strategic production centres. This form of positional camouflage could be quite elaborate, and even include false houses and cars.[86] With the threat from nuclear weapons in the post-war era such elaborate camouflage was no longer seen as useful, as a direct hit would not be necessary with strategic nuclear weapons to destroy infrastructure. The Soviet Union's doctrine of military deception defines the need for surprise through means including camouflage, based on experiences such as the Battle of Kursk where camouflage helped the Red Army to overwhelm a powerful enemy.[87][88][89]

Application

Uniforms

The role of uniform is not only to hide each soldier, but also to identify friend from foe. Issue of the "Frogskin" uniforms to US troops in Europe during the Second World War was halted as it was too often mistaken for the disruptively patterned German uniform worn by the Waffen-SS.[90] Camouflage uniforms need to be made and distributed to a large number of soldiers. The design of camouflage uniforms therefore involves a tradeoff between camouflaging effect, recognizability, cost, and manufacturability.[2]

Armies facing service in different theatres may need several different camouflage uniforms. Separate issues of temperate/jungle and desert camouflage uniforms are common. Patterns can to some extent be adapted to different terrains by adding means of fastening pieces of vegetation to the uniform. Helmets often have netting covers; some jackets have small loops for the same purpose.[2] Being able to find appropriate camouflage vegetation or in other ways modify the issued battle uniform to suit the local terrain is an important skill for infantry soldiers.[7]

Countries in boreal climates often need snow camouflage, either by having reversible uniforms or simple overgarments.[91][92]

Land vehicles

The purpose of vehicle and equipment camouflage differs from personal camouflage in that the primary threat is aerial reconnaissance. The goal is to disrupt the characteristic shape of the vehicle, to reduce shine, and to make the vehicle difficult to identify even if it is spotted.[93]

Paint is the least effective measure, but forms a basis for other techniques. Military vehicles often become so dirty that pattern-painted camouflage is not visible, and although matt colours reduce shine, a wet vehicle can still be shiny, especially when viewed from above. Patterns are designed to make it more difficult to interpret shadows[94] and shapes.[95] The British Army adopted a disruptive scheme for vehicles operating in the stony desert of the North African Campaign and Greece, retrospectively known as the Caunter scheme. It used up to six colours applied with straight lines.[96]

The British Army's Special Air Service used pink as the primary colour on its desert-camouflaged Land Rover Series IIA patrol vehicles, nicknamed Pink Panthers;[97] the colour had been observed to be indistinguishable from sand at a distance.

Nets can be effective at defeating visual observation. Traditional camouflage nets use a textile 'garnish' to generate an apparent texture with a depth of shadow created beneath it, and the effect can be reinforced with pieces of vegetation.[93] Modern nets tend to be made of a continuous woven material, which is easier to deploy over a vehicle and lack the "windows" between patches of garnish of traditional nets. Some nets can remain in place while vehicles move. Simple nets are less effective in defeating radar and thermal sensors. Heavier, more durable "mobile camouflage systems", essentially conformal duvets with thermal and radar properties, provide a degree of concealment without the delay caused by having to spread nets around a vehicle.[98][99]

Active camouflage for vehicles, using heated or cooled Peltier plates to match the infrared background, has been prototyped in industry but has not yet been put into production.[100]

Ships

.jpg)

Until the 20th century, naval weapons had a short range, so camouflage was unimportant for ships, and for the men on board them. Paint schemes were selected on the basis of ease of maintenance or aesthetics, typically buff upperworks (with polished brass fittings) and white or black hulls. Around the start of the 20th century, the increasing range of naval engagements, as demonstrated by the Battle of Tsushima, prompted the introduction of the first camouflage, in the form of some solid shade of gray overall, in the hope that ships would fade into the mist.[101][102]

.jpg)

First and Second World War dazzle camouflage, pioneered by English artist Norman Wilkinson, was used not to make ships disappear, but to make them seem smaller or faster, to encourage misidentification by an enemy, and to make the ships harder to hit.[103] In the Second World War, the Royal Canadian Navy trialled a form of active camouflage, counter-illumination, using diffused lighting to prevent ships from appearing as dark shapes against a brighter sky during the night. It reduced visibility by up to 70%, but was unreliable and never went into production.

After the Second World War, the use of radar made camouflage generally less effective. However, camouflage may have helped to protect US warships from Vietnamese shore batteries using optical rangefinders.[102]

Coastal patrol boats such as those of the Norwegian, Swedish and Indonesian navies continue to use terrestrial style disruptively patterned camouflage.[105]

Aircraft

Aircraft camouflage faces the challenge that an aircraft's background varies widely, according to whether the observer is above or below the aircraft, and with the background, e.g. farmland or desert. Aircraft camouflage schemes have often consisted of a light colour underneath and darker colours above.[106][lower-alpha 2]

Other camouflage schemes acknowledge that aircraft may be seen at any angle and against any background while in combat, so aircraft are painted all over with a disruptive pattern or a neutral colour such as gray.[6]

Second World War maritime patrol aircraft such as the Consolidated PBY Catalina flying boat were painted white, as aircraft generally appear dark against the sky (including at night), and hence are least visible when painted in as light a colour as possible.[107] The problem of appearing dark against the sky was explored in the U.S. Navy's Yehudi lights project in 1943, using counter-illumination to raise the average brightness of a plane, when seen head-on, from a dark shape to the same as the sky. The experiments worked, enabling an aircraft to approach to within 2 miles (3.2 km) before being seen, whereas aircraft without the lights were noticed 12 miles (19 km) away.[108]

The higher speeds of modern aircraft, and the reliance on radar and missiles in air combat have reduced the value of visual camouflage, while increasing the value of electronic "stealth" measures. Modern paint is designed to absorb electromagnetic radiation used by radar, reducing the signature of the aircraft, and to limit the emission of infrared light used by heat seeking missiles to detect their target. Further advances in aircraft camouflage are being investigated in the field of active camouflage.[108]

In fashion and art

Fashion and the "Dazzle Ball"

The transfer of camouflage patterns from battle to exclusively civilian uses is not recent. Dazzle camouflage inspired a trend of dazzlesque patterns used on clothing in England, starting in 1919 with the "Dazzle Ball" held by Chelsea Arts Club. Those attending wore dazzle-patterned black and white clothing, influencing twentieth-century fashion and art via postcards (see illustration) and magazine articles.[109][110] The Illustrated London News announced

The scheme of decoration for the great fancy dress ball given by the Chelsea Arts Club at the Albert Hall, the other day, was based on the principles of 'Dazzle', the method of 'camouflage' used during the war in the painting of ships ... The total effect was brilliant and fantastic.[109][111]

Camouflage in art

While many artists helped to develop camouflage during and since World War I, the disparate sympathies of the two cultures restrained the use of "militaristic" forms other than in the work of war artists. Since the 1960s, several artists have exploited the symbolism of camouflage. For example, Andy Warhol's 1986 camouflage series was his last major work, including Camouflage Self-Portrait.[112] Alain Jacquet created many camouflage works from 1961 to the 1970s.[113] Ian Hamilton Finlay's 1973 Arcadia was a screenprint of a leafily-camouflaged tank, "an ironic parallel between this idea of a natural paradise and the camouflage patterns on a tank", as the Tate Collection describes it.[114] Veruschka, the pseudonym of Vera von Lehndorff and Holger Trülzsch, created "Nature, Signs & Animals" and "Mimicry-Dress-Art" in 1970–1973.[115] Thomas Hirschhorn made Utopia : One World, One War, One Army, One Dress in 2005.[116]

War protesters and fashionistas

In the US in the 1960s, military clothing became increasingly common (mostly olive drab rather than patterned camouflage); it was often found worn by anti-war protestors, initially within groups such as Vietnam Veterans Against the War but then increasingly widely as a symbol of political protest.[117]

Fashion often uses camouflage as inspiration – attracted by the striking designs, the "patterned disorder" of camouflage, its symbolism (to be celebrated or subverted), and its versatility. Early designers include Marimekko (1960s), Jean-Charles de Castelbajac (1975–), Stephen Sprouse (using Warhol prints, 1987–1988), and Franco Moschino (1986), but it was not until the 1990s that camouflage became a significant and widespread facet of dress from streetwear to high-fashion labels – especially the use of "faux-camouflage". Producers using camouflage in the 1990s and beyond include: John Galliano for Christian Dior,[118] Marc Jacobs for Louis Vuitton, Comme des Garçons, Chanel, Tommy Hilfiger, Dolce & Gabbana, Issey Miyake, Armani, Yves Saint-Laurent.[117]

Companies closely associated with camouflage patterns include 6876, A Bathing Ape, Stone Island, Stüssy, Maharishi, mhi, Zoo York, Addict, and Girbaud, using and overprinting genuine military surplus fabric; others use camouflage patterns in bright colours such as pink or purple. Some, such as Emma Lundgren and Stüssy, have created their own designs or integrated camouflage patterns with other symbols.[119][120]

Restrictions

Some countries such as Barbados, Aruba, and other Caribbean nations have laws prohibiting camouflage clothing from being worn by non-military personnel, including tourists and children.[60] Civilian possession of camouflage is still banned in Zimbabwe.[121]

See also

- Camouflage (1944 film), World War II camouflage training film produced by the US Army Air Forces

Notes

- TTsMKK is short for "TryokhTsvetniy Maskirovochniy Kamuflirovanniy Kombinezon", three colour disguise camouflage overalls.

- The dark above, light below camouflage pattern is often called countershading, but its function is not to flatten out shadow as in Thayer's law, but to camouflage against two different backgrounds.

References

- Newark 2007, p. 8.

- Brayley 2009

- Behrens 2003

- Newark 2007, p. 160.

- "Camouflage Face Paints". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- Richardson 2001

- US Army 2013

- US Army 2009.

- Cabela's 2012

- Freedberg 2012.

- Davies 2012.

- Talas, Baddeley & Cuthill 2017

- Peterson 2001

- War Department 2013.

- Anon 2012.

- Bundesheer 2012.

- Katz 1988.

- Craemer 2012.

- Dougherty 2017, p. 69.

- Kennedy 2013.

- Craemer 2007

- Strikehold 2010.

- Engber 2012.

- Rao & Mahulikar 2002

- Summers 2004.

- Kopp 1989.

- Harris 2013.

- Shabbir 2002.

- Zimmerman 2000.

- GlobalSecurity 2012.

- Letowski 2012.

- Plaster 1993.

- BBC 2006.

- FAS 1998.

- Casson 1995.

- Murphy 1917

- Sumner 2003.

- Kaempffert 1919.

- Chartrand 2013.

- Simcoe 1784.

- Haythornthwaite 2002, p. 20.

- von Pivka 2002.

- "Khaki Uniform 1848–49: First Introduction by Lumsden and Hodson". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 82 (Winter): 341–347. 2004.

- Hodson, W.S.R.; edited by George H. Hodson (1859). Twelve Years of a Soldier's Life in India, being extracts from the letters of the late Major WSR Hodson. John W. Parker and Son.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Oxford Dictionary

- Barthorp 1988, Volume 3, pp. 24–37.

- Myatt 1994.

- Barthorp 1988, Volume 4, pp. 24–33.

- Chappell 2003.

- Showalter 2004.

- Louis Guingot: Camouflage jacket, note from the Lorraine Museum, Palais des Ducs de Lorraine, France

- Crowdy 2007

- The Encyclopædia Britannica. 30 (11 ed.). 1922. p. 541.

- Danton 1915.

- Behrens 2005

- Forbes 2009, pp. 104–107.

- Boucher 2009

- Antique Photos 2012.

- Forbes 2009, pp. 72–73

- Blechman & Newman 2004

- Forbes 2009, pp. 82–83.

- Adams 2011.

- Forbes 2009, p. 104

- Forbes 2009, p. 101.

- Forbes 2009, p. 106.

- Newark 2007, p. 54.

- Walker, Margaret F. M. (6 April 2016). "Beauty and the Battleship". History Today. London, England: History Today. ISSN 0018-2753. Archived from the original on 29 June 2018. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- "Women Camouflage Guns in France". The Orlando Evening Star. Orlando, Florida. 27 December 1917. p. 1. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- "French Women Aid Camouflage". Muncie, Indiana: The Star Press. 20 October 1918. p. 10. Retrieved 29 June 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Davis 1998.

- Ferguson 1996

- Cott 1940, p. 53.

- Pilawskii 2003.

- Greer 1980.

- Massimello & Apostolo 2000.

- Thorpe 1968.

- Bishop 2010.

- Restayn 2005.

- "Country Women: Camouflage Nets Project". Glen Innes, New South Wales, Australia: The Glen Innes Examiner. 15 November 1941. p. 6. Retrieved 30 June 2018 – via Newspaperarchive.com.

- "In Their Spare Time". The Glenboro Western Prairier Gazette. Glenboro, Manitoba, Canada. 5 March 1942. p. 3. Retrieved 30 June 2018 – via Newspaperarchive.com.

- "Making Camouflage Nets for the Army". The Auckland Star. Auckland, New Zealand. 27 August 1941. p. 13. Retrieved 30 June 2018 – via Newspaperarchive.com.

- "Women Work on Camouflage Nets in Homes". The Standard-Examiner. Ogden, Utah. 16 July 1944. p. 24. Retrieved 30 June 2018 – via Newspaperarchive.com.

- Stroud 2012

- Barkas & Barkas 1952.

- Casey 1951, pp. 138–140.

- Wade 2012.

- Smith 1988.

- Glantz 1989, p. 6 and passim.

- Clark 2011, p. 278.

- Borsarello 1999.

- Bull, Stephen (2004). Encyclopedia of Military Technology and Innovation. Greenwood. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-57356-557-8.

- Englund, Peter (2011). The Beauty And The Sorrow: An intimate history of the First World War. Profile Books. p. 211. ISBN 978-1-84765-430-4.

- War Department 1944

- Cott 1940, pp. 104–111.

- Cott 1940, p. 48.

- Starmer 2005.

- SAS 2013.

- Krone 2013.

- Blücher 2013.

- Schechter, Erik (1 July 2013). "Whatever Happened to Counter-Infrared Camouflage?". Popular Mechanics. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- Prinzeugen 2012.

- Sumrall 1973

- Wilkinson 1939

- Kitsune 2013.

- Shaw 1985.

- Tinbergen 1953.

- Douglass & Sweetman 1997

- Forbes 2009, p. 100

- Anon 1918.

- Anon 1919.

- Warhol 1986

- Grimes 2008

- Tate 2008.

- Lehndorff & Trülzsch 2011.

- Tanchelev 2006

- Dillon 2011

- Galliano 2006

- Lundgren 2011

- Stüssy 2012

- "'DJ Squila', sustained serious head injuries". The Zimbabwean. 30 October 2008. Archived from the original on 8 November 2014.

Sources

- Adams, Henry (March 2011). "Ornithology, Infantry and Abstraction". Art & Antiques.

- Anon (July 1918). "'Camouflage' in War and Nature". Arts & Decoration: 175.

- Anon (22 March 1919). "Illustrated London News". The Great Dazzle Ball at the Albert Hall: The Shower of Bomb Balloons and Some Typical Costumes. No. 154. pp. 414–415.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Anon (2012). "New Army Combat Uniform". Army News Service. About.com. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

Black is no longer useful on the uniform because it is not a color commonly found in nature. The drawback to black is that its color immediately catches the eye, he added

- Antique Photos (2012). "German steel helmets". Antique Photos. Retrieved 2 October 2012.

- Barkas, Geoffrey; Barkas, Natalie (1952). The Camouflage Story (from Aintree to Alamein). Cassell.

- Barthorp, Michael (1988). The British Army on Campaign 1816–1902. Osprey Publishing.

- BBC (21 January 2006). "Degaussing Ships in Falmouth Docks". BBC. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- Behrens, Roy R. (2003). False Colours: Art, Design, and Modern Camouflage. Bobolink Books. ISBN 978-0-9713244-0-4.

- Behrens, Roy R. (Summer 2005). "Art Culture and Camouflage". Tate Etc (4).

- Bishop, Chris (2010). Luftwaffe squadrons 1939–45. London: Amber. ISBN 978-1-904687-62-7.

- Blechman, Hardy; Newman, Alex (2004). DPM: Disruptive Pattern Material. DPM. ISBN 0-9543404-0-X.

- Blücher (2013). "Camouflage Net: Multispectral Camouflage Systems". BLÜCHER SYSTEMS. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- "Alighiero Boetti, "Mimetico", 1967". Museo Madre. Archived from the original on 23 November 2012. Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- Borsarello, J.F. (1999). Camouflage uniforms of European and NATO armies : 1945 to the present. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Pub. ISBN 0-7643-1018-6.

- Boucher, W. Ira. (2009). "An Illustrated History of World War One". German Lozenge Camouflage. Retrieved 2 November 2009.

- Brayley, Martin J. (2009). Camouflage uniforms : international combat dress 1940–2010. Ramsbury: Crowood. ISBN 978-1-84797-137-1.

- Bundesheer (2012). "Die Uniform". Österreichs Bundesheer. Austrian Army (Bundesheer). Retrieved 3 September 2012.

- Cabela's (2012). "Camo Pattern Buyer's Guide". Cabela's Canada. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- Casey, Hugh J., ed. (1951). Airfield and Base Development. Engineers of the Southwest Pacific. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office.

- "Israel". Camopedia. 27 March 2011. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- Casson, Lionel (1995). Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World. JHU Press. p. 235. ISBN 0-8018-5130-0.

- Chappell, M. (2003). The British Army in World War I (1). Osprey. p. 37.

- Chartrand, René (2013). "Miscellaneous Notes on Rangers". Military Heritage. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- Clark, Lloyd (2011). Kursk: the greatest battle, eastern front 1943. Headline.

- Cott, Hugh B. (1940). Adaptive Coloration in Animals. Methuen.

- Craemer, Guy (2007). "CADPAT or MARPAT Camouflage". Who did it first; Canada or the US?. Hyperstealth. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- Craemer, Guy (2012). "Dual Texture – U.S. Army digital camouflage". United Dynamics. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- Crowdy, Terry (2007). Military Misdemeanors. p. 149. ISBN 978-1-84603-148-9.

- Danton, Louis (1915). "Cubisme et camouflage - L'Histoire par l'image". histoire-image.org (in French). Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- Davies, W. (2012). "Berlin Brigade Urban Paint Scheme". Newsletter. Ex-Military Land Rover Association. Archived from the original on 12 March 2013. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- Davis, Brian L. (1998). German Army uniforms and insignia : 1933–1945. London: Brockhampton Press. ISBN 978-1-86019-869-4.

- Dillon, Ronan (24 February 2011). "Protesters in Camouflage". The Re-Appropriation of Camouflage from military use into civilian clothing. This Greedy Pig.com. Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- Dougherty, Martin J. (2017). Camouflage at War: An Illustrated Guide from 1914 to the Present Day. Amber Books. ISBN 978-0-7858-3509-7.

- Douglass, Steve; Sweetman, Bill (1997). "Hiding in Plane Sight: Stealth aircraft own the night. Now they want the day". Popular Science: 54–59. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- Engber, D. (5 July 2012). "Lost in the Wilderness, the military's misadventures in pixellated camouflage". State. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- FAS (12 December 1998). "Degaussing". FAS. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- Ferguson, Gregor (1996). The Paras 1940–1984. Osprey (Reed Consumer Books Ltd.). ISBN 0-85045-573-1.

- Forbes, Peter (2009). Dazzled and Deceived: Mimicry and Camouflage. Yale. ISBN 978-0300125399.

- Freedberg, S. J., Jr. (25 June 2012). "Army Drops Universal Camouflage After Spending Billions". Aol Defence. Archived from the original on 31 August 2012. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- Galliano (9 September – 16 December 2006). "Love and War: The Weaponized Woman". John Galliano for Christian Dior, silk camouflage evening dress. The Museum at FIT. Archived from the original on 3 September 2006. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- Glantz, David M. (1989). Soviet Military Deception in the Second World War. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7146-3347-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- GlobalSecurity (2012). "Stealth Helicopter: MH-X Advanced Special Operations Helicopter". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 28 April 2012.

- Greer (1980). Dana Bell; illustrated by Don (eds.). Air Force colors. Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications. ISBN 0-89747-108-3.

- Grimes, William (9 September 2008). "Alain Jacquet, Playful Pop Artist, Dies at 69". New York Times.

- Harris, Tom (2013). "How Stealth Bombers Work". How Stuff Works. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- Haythornthwaite, Philip (2002). British rifleman, 1797–1815. Christa Hook (illus.). Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 1-84176-177-X.

- Katz, Sam (1988). Israeli Elite Units since 1948. United Kingdom: Osprey Publishing. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-85045-837-4.

- Kaempffert, Waldemar (April 1919). "Fighting the U-Boat with Paint: How American and English artists taught sailors to dazzle the U-Boat". Popular Science Monthly. New York City. 94 (4): 17.

- Kennedy, Pagan (10 May 2013). "Who Made That Digital Camouflage?". The New York Times.

- Kitsune (2013). "Norwegian Skjold class Surface Effect Patrol Boat". Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- Kopp, C. (November 1989). "Optical Warfare – The New Frontier". Australian Aviation.

- Krone (2013). "Signature management: passive protection". Krone Technology. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- Lehndorff, Vera; Trülzsch, Holger (2011). "Vera Lehndorff & Holger Trülzsch". (Portfolio of photographs). Veruschka.net. Archived from the original on 26 November 2011. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- Letowski, T.R. (2012). Owning the Environment: Stealth Soldier— Research Outline. Aberdeen Proving Ground, MD: U.S. Army Research Laboratory. p. 20.

- Lundgren, Emma (2011). "Emma Lundgren: Camouflage". Camouflage (fashion). emmalundgren.com. Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- Massimello, Giovanni; Apostolo, Giorgio (2000). Italian aces of World War 2 (1 ed.). Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 1-84176-078-1.

- Murphy, Robert Cushman (January 1917). "Marine camouflage". The Brooklyn Museum Quarterly. Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences. 4–6: 35–39.

- Myatt, F. (1994). The illustrated encyclopedia of 19th century firearms: an illustrated history of the development of the world's military firearms during the 19th century. New York: Crescent Books. ISBN 0-517-27786-7.

- Newark, Tim (2007). Camouflage. Thames & Hudson.

- Peterson, D. (2001). Waffen-SS Camouflage Uniforms and Post-war Derivatives. Crowood. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-86126-474-9.

- Pilawskii, Erik (2003). Soviet Air Force fighter colours : 1941–1945. Hersham: Classic. ISBN 1-903223-30-X.

- Plaster, John L. (1993). The ultimate sniper : an advanced training manual for military & police snipers. Boulder, Colorado: Paladin Press. ISBN 0-87364-704-1.

- Prinzeugen (2012). "Schnellboot: An Illustrated Technical History". Prinz Eugen. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- Rao, G.A.; Mahulikar, S. P. (2002). "Integrated review of stealth technology and its role in airpower". Aeronautical Journal. 106 (1066): 629–641.

- Restayn, Jean (2005). Encyclopaedia of AFVs of WWII. Volume 1: Tanks. Paris: Casemate. ISBN 2-915239-47-9.

- Richardson, Doug (2001). Stealth warplanes. Osceola, WI: MBI Pub. Co. ISBN 0-7603-1051-3.

- SAS (2013). "Mobility Troop - SAS Land Rovers". Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- Shabbir, Usman (2002). "Highlights from IDEAS 2002". ACIG Special Reports. Air Combat Information Group.

- Shaw, Robert L. (1985). Fighter Combat : Tactics and Maneuvering. Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-059-9.

- Showalter, Dennis E. (2004). Tannenberg:clash of empires 1914. p. 148. ISBN 1-57488-781-5.

- Simcoe, John Graves (1784). A Journal of the Operations of the Queen's Rangers, from the end of the year 1777, to the conclusion of the Late American War. Archived from the original on 12 December 2003. Retrieved 2 October 2012.

- Smith, Charles L (Spring 1988). "Soviet Maskirovka". Airpower Journal.

- Starmer, Mike (2005). The Caunter Scheme: British World War Two Camouflage Schemes. Partizan Press.

- Strikehold (2010). "Making Sense of Digital Camouflage". Strikehold. Archived from the original on 30 November 2012. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

- Stroud, Rick (2012). The Phantom Army of Alamein: How the Camouflage Unit and Operation Bertram Hoodwinked Rommel. Bloomsbury.

- Stüssy (2012). "Stüssy Camo". Camouflage (fashion). stussy.com. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- Summers, Chris (10 June 2004). "Stealth ships steam ahead". BBC News. Retrieved 27 May 2010.

- Sumner, Graham (2003). Roman Military Clothing: AD 200–400. 2. Osprey Publishing. p. 24. ISBN 1-84176-559-7.

- Sumrall, Robert F. (February 1973). "Ship Camouflage (WWII): Deceptive Art". United States Naval Institute Proceedings: 67–81.

- Talas, Laszlo; Baddeley, Roland J.; Cuthill, Innes C. (2017). "Cultural evolution of military camouflage". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 372 (1724): 20160351. doi:10.1098/rstb.2016.0351. PMC 5444070. PMID 28533466.

- Tanchelev, Gloria (10 March – 13 May 2006). "Thomas Hirschhorn". Feature: Reviews: Thomas Hirschhorn: UTOPIA UTOPIA=ONE WORLD ONE WAR ONE ARMY ONE DRESS. Stretcher.org. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- Tate (July 2008). "Ian Hamilton Finlay 1925–2006: Arcadia". Arcadia, 1973. Tate Collection. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- Thorpe, Donald W. (1968). Japanese Army Air Force camouflage and markings, World War II. Translated by Yasuo Oishi. Fallbrook, California: Aero. ISBN 0-8168-6579-5.

- Tinbergen, Niko (1953). The Herring Gull's World. Collins. p. 14. ISBN 0-00-219444-9.

white has proved to be the most efficient concealing coloration for aircraft on anti-submarine patrol

- US Army (2009). Photosimulation Camouflage Detection Test. Natick, MA: U.S. Army Natick Soldier Research, Development and Engineering Center. p. 27. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

Overall, in a woodland environment, the lighter coloured patterns were detected at greater distances than the darker patterns. The opposite was found in desert and urban conditions. These data confirm intuition on environment-specific patterns: woodland patterns perform best in woodland environments, and desert patterns perform best in desert environments.

- US Army (2013). FM 21–76 US ARMY SURVIVAL MANUAL (PDF). U.S. Department of the Army. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- von Pivka, Otto (2002). The Portuguese Army of the Napoleonic wars. Michael Roffe (illus.). Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 0-85045-251-1.

- Wade, Lisa (2012). "Camouflaging Airports and Plants During WWII". Sociological Images. Archived from the original on 14 June 2012. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- War Department (1944). FM 5-20B Field Manual: Camouflage of Vehicles. U.S. War Department, Corps of Engineers.

- War Department (2013). Field Manual: FM 5-20A: Camouflage of Individuals and Infantry Weapons. United States War Department. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- Warhol, Andy (1986). "Camouflage Self-portrait". Philadelphia Museum of Art. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- Wilkinson, Norman (4 April 1939). "Letter to The Times on Camouflage". The Times. London.

- Zimmerman, Stan (2000). "Silence Makes Perfect". Submarine Technology for the 21st Century (2nd ed.). Victoria, British Columbia: Trafford Publishing. pp. 103–105. ISBN 978-1-55212-330-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Military camouflage. |

- "Abbott Thayer's Camouflage Demonstrations: Countershading, Disruption and Background Picturing"

- Shipcamouflage.com

- Roy R. Behrens – Art and Camouflage: An Annotated Bibliography

- Guy Hartcup – Camouflage: A History of Concealment and Deception in War (1980)

- WWII War Department Field Manual FM 5-20B: Camouflage of Vehicles (1944)

- Patterns compared

- Camouflage paint colours

- Cécile Coutin: Camouflage, in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

.jpg)