Lie

A lie is an assertion that is believed to be false, typically used with the purpose of deceiving someone.[1][2][3][4] The practice of communicating lies is called lying. A person who communicates a lie may be termed a liar. Lies may serve a variety of instrumental, interpersonal, or psychological functions for the individuals who use them. Generally, the term "lie" carries a negative connotation, and depending on the context a person who communicates a lie may be subject to social, legal, religious, or criminal sanctions.

Types and associated terms

- A barefaced, bald-faced or bold-faced lie is an impudent, brazen, shameless, flagrant, or audacious lie that is sometimes but not always undisguised and that it is even then not always obvious to those hearing it.[5]

- A big lie is one that attempts to trick the victim into believing something major, which will likely be contradicted by some information the victim already possesses, or by their common sense. When the lie is of sufficient magnitude it may succeed, due to the victim's reluctance to believe that an untruth on such a grand scale would indeed be concocted.[6]

- A blue lie is a form of lying that is told purportedly to benefit a collective or "in the name of the collective good". The origin of the term "blue lie" is possibly from cases where police officers made false statements to protect the police force or to ensure the success of a legal case against an accused.[7] This differs from the Blue wall of silence in that a blue lie is not an omission but a stated falsehood.

- To bluff is to pretend to have a capability or intention one does not possess.[6] Bluffing is an act of deception that is rarely seen as immoral when it takes place in the context of a game, such as poker, where this kind of deception is consented to in advance by the players. For instance, gamblers who deceive other players into thinking they have different cards to those they really hold, or athletes who hint they will move left and then dodges right is not considered to be lying (also known as a feint or juke). In these situations, deception is acceptable and is commonly expected as a tactic.

- Bullshit (also B.S., bullcrap, bull) does not necessarily have to be a complete fabrication. While a lie is related by a speaker who believes what is said is false, bullshit is offered by a speaker who does not care whether what is said is true because the speaker is more concerned with giving the hearer some impression. Thus bullshit may be either true or false, but demonstrates a lack of concern for the truth that is likely to lead to falsehoods.[8]

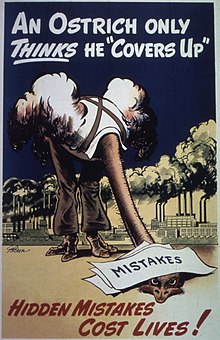

- A cover-up may be used to deny, defend, or obfuscate a lie, errors, embarrassing actions, or lifestyle, and/or lie(s) made previously.[6] One may deny a lie made on a previous occasion, or alternatively, one may claim that a previous lie was not as egregious as it was. For example, to claim that a premeditated lie was really "only" an emergency lie, or to claim that a self-serving lie was really "only" a white lie or noble lie. This should not be confused with confirmation bias in which the deceiver is deceiving themselves.

- Defamation is the communication of a false statement that harms the reputation of an individual person, business, product, group, government, religion, or nation.[6]

- To deflect is to avoid the subject that the lie is about, not giving attention to the lie. When attention is given to the subject the lie is based around, deflectors ignore or refuse to respond. Skillful deflectors are passive-aggressive, who when confronted with the subject choose to ignore and not respond.[9]

- Disinformation is intentionally false or misleading information that is spread in a calculated way to deceive target audiences.[6]

- An exaggeration occurs when the most fundamental aspects of a statement are true, but only to a certain degree. It also is seen as "stretching the truth" or making something appear more powerful, meaningful, or real than it is. Saying that someone devoured most of something when they only ate half would be considered an exaggeration. An exaggeration might be easily found to be a hyperbole where a person's statement (i.e. in informal speech, such as "He did this one million times already!") is meant not to be understood literally.[6]

- Fake news is supposed to be a type of yellow journalism that consists of deliberate misinformation or hoaxes spread via traditional print and broadcast news media or online social media.[10] Sometimes the term is applied as a deceptive device to deflect attention from uncomfortable truths and facts, however.

- A fib is a lie that is easy to forgive due to its subject being a trivial matter; for example, a child may tell a fib by claiming that the family dog broke a household vase, when the child was the one who broke it.[6]

- Fraud refers to the act of inducing another person or people to believe a lie in order to secure material or financial gain for the liar. Depending on the context, fraud may subject the liar to civil or criminal penalties.[11]

- A half-truth is a deceptive statement that includes some element of truth. The statement might be partly true, the statement may be totally true, but only part of the whole truth, or it may employ some deceptive element, such as improper punctuation or double meaning, especially if the intent is to deceive, evade, blame, or misrepresent the truth.[12]

- An honest lie (or confabulation) may be identified by verbal statements or actions that inaccurately describe the history, background, and present situations. There is generally no intent to misinform and the individual is unaware that their information is false. Because of this, it is not technically a lie at all since, by definition, there must be an intent to deceive for the statement to be considered a lie.

- Jocose lies are lies meant in jest, intended to be understood as such by all present parties. Teasing and irony are examples. A more elaborate instance is seen in some storytelling traditions, where the storyteller's insistence that the story is the absolute truth, despite all evidence to the contrary (i.e., tall tale), is considered humorous. There is debate about whether these are "real" lies, and different philosophers hold different views. The Crick Crack Club in London arranges a yearly "Grand Lying Contest" with the winner being awarded the coveted "Hodja Cup" (named for the Mulla Nasreddin: "The truth is something I have never spoken."). The winner in 2010 was Hugh Lupton. In the United States, the Burlington Liars' Club awards an annual title to the "World Champion Liar."[13]

- Lie-to-children is a phrase that describes a simplified explanation of technical or complex subjects as a teaching method for children and laypeople. While lies-to-children are useful in teaching complex subjects to people who are new to the concepts discussed, they can promote the creation of misconceptions among the people who listen to them. The phrase has been incorporated by academics within the fields of biology, evolution, bioinformatics, and the social sciences. Media use of the term has extended to publications including The Conversation and Forbes.

- Lying by omission, also known as a continuing misrepresentation or quote mining, occurs when an important fact is left out in order to foster a misconception. Lying by omission includes the failure to correct pre-existing misconceptions. For example, when the seller of a car declares it has been serviced regularly, but does not mention that a fault was reported during the last service, the seller lies by omission. It may be compared to dissimulation. An omission is when a person tells most of the truth, but leaves out a few key facts that therefore, completely obscures the truth.[9]

- Lying in trade occurs when the seller of a product or service may advertise untrue facts about the product or service in order to gain sales, especially by competitive advantage. Many countries and states have enacted consumer protection laws intended to combat such fraud.

- A memory hole is a mechanism for the alteration or disappearance of inconvenient or embarrassing documents, photographs, transcripts, or other records, such as from a website or other archive, particularly as part of an attempt to give the impression that something never happened.[14][15]

- Minimization is the opposite of exaggeration. It is a type of deception[16] involving denial coupled with rationalization in situations where complete denial is implausible.

- Mutual deceit is a situation wherein lying is both accepted and expected[17] or that the parties mutually accept the deceit in question.[18] This can be demonstrated in the case of a poker game wherein the strategies rely on deception and bluffing to win.[18]

- A noble lie, which also could be called a strategic untruth, is one that normally would cause discord if uncovered, but offers some benefit to the liar and assists in an orderly society, therefore, potentially being beneficial to others. It is often told to maintain law, order, and safety.

- In psychiatry, pathological lying (also called compulsive lying, pseudologia fantastica, and mythomania) is a behavior of habitual or compulsive lying.[20][21] It was first described in the medical literature in 1891 by Anton Delbrueck.[21] Although it is a controversial topic,[21] pathological lying has been defined as "falsification entirely disproportionate to any discernible end in view, may be extensive and very complicated, and may manifest over a period of years or even a lifetime".[20] The individual may be aware they are lying, or may believe they are telling the truth, being unaware that they are relating fantasies.

- Perjury is the act of lying or making verifiably false statements on a material matter under oath or affirmation in a court of law, or in any of various sworn statements in writing. Perjury is a crime, because the witness has sworn to tell the truth and, for the credibility of the court to remain intact, witness testimony must be relied on as truthful.[6]

- A polite lie is a lie that a politeness standard requires, and that usually is known to be untrue by both parties. Whether such lies are acceptable is heavily dependent on culture. A common polite lie in international etiquette may be to decline invitations because of "scheduling difficulties", or due to "diplomatic illness". Similarly, the butler lie is a small lie that usually is sent electronically and is used to terminate conversations or to save face.[22]

- Puffery is an exaggerated claim typically found in advertising and publicity announcements, such as "the highest quality at the lowest price", or "always votes in the best interest of all the people". Such statements are unlikely to be true – but cannot be proven false and so, do not violate trade laws, especially as the consumer is expected to be able to determine that it is not the absolute truth.[23]

- The phrase "speaking with a forked tongue" means to deliberately say one thing and mean another or, to be hypocritical, or act in a duplicitous manner. This phrase was adopted by Americans around the time of the Revolution, and may be found in abundant references from the early nineteenth century – often reporting on American officers who sought to convince the Indigenous peoples of the Americas with whom they negotiated that they "spoke with a straight and not with a forked tongue" (as for example, President Andrew Jackson told members of the Creek Nation in 1829).[24] According to one 1859 account, the proverb that the "white man spoke with a forked tongue" originated in the 1690s, in the descriptions by the indigenous peoples of French colonials in America inviting members of the Iroquois Confederacy to attend a peace conference, but when the Iroquois arrived, the French had set an ambush and proceeded to slaughter and capture the Iroquois.[25]

- A weasel word is an informal term[26] for words and phrases aimed at creating an impression that a specific or meaningful statement has been made, when in fact only a vague or ambiguous claim has been communicated, enabling the specific meaning to be denied if the statement is challenged. A more formal term is equivocation.

- A white lie is a harmless or trivial lie, especially one told in order to be polite or to avoid hurting someone's feelings or stopping them from being upset by the truth.[27][28][29] A white lie also is considered a lie to be used for greater good (pro-social behavior). It sometimes is used to shield someone from a hurtful or emotionally-damaging truth, especially when not knowing the truth is deemed by the liar as completely harmless.

Consequences

The potential consequences of lying are manifold; some in particular are worth considering. Typically lies aim to deceive, when deception is successful, the hearer ends up acquiring a false belief (or at least something that the speaker believes to be false). When deception is unsuccessful, a lie may be discovered. The discovery of a lie may discredit other statements by the same speaker, staining his reputation. In some circumstances, it may also negatively affect the social or legal standing of the speaker. Lying in a court of law, for instance, is a criminal offense (perjury).[30]

Hannah Arendt spoke about extraordinary cases in which an entire society is being lied to consistently. She said that the consequences of such lying are "not that you believe the lies, but rather that nobody believes anything any longer. This is because lies, by their very nature, have to be changed, and a lying government has constantly to rewrite its own history. On the receiving end you get not only one lie—a lie which you could go on for the rest of your days—but you get a great number of lies, depending on how the political wind blows."[31]

Detection

The question of whether lies can be detected reliably through nonverbal means is a subject of some controversy.[32]

Polygraph "lie detector" machines measure the physiological stress a subject endures in a number of measures while giving statements or answering questions. Spikes in stress indicators are purported to reveal lying. The accuracy of this method is widely disputed. In several well-known cases, application of the technique was proven to have been deceived. Nonetheless, it remains in use in many areas, primarily as a method for eliciting confessions or employment screening. The unreliability of polygraph results are the basis of such evaluations not being admissible as court evidence and, generally, the technique is perceived to be pseudoscience.[33]

A recent study found that composing a lie takes longer than telling the truth and thus, the time taken to answer a question may be used as a method of lie detection,[34] however, it also has been shown that instant answers with a lie may be proof of a prepared lie. A recommendation provided to resolve that contradiction is to try to surprise the subject and find a midway answer, not too quick, nor too long.[35]

Ethics

Aristotle believed no general rule on lying was possible, because anyone who advocated lying could never be believed, he said.[36] Although the philosophers, St. Augustine, St. Thomas Aquinas, and Immanuel Kant, condemned all lying,[37] Thomas Aquinas did advance an argument for lying, however. According to all three, there are no circumstances in which, ethically, one may lie. Even if the only way to protect oneself is to lie, it is never ethically permissible to lie even in the face of murder, torture, or any other hardship. Each of these philosophers gave several arguments for the ethical basis against lying, all compatible with each other. Among the more important arguments are:

- Lying is a perversion of the natural faculty of speech, the natural end of which is to communicate the thoughts of the speaker.

- When one lies, one undermines trust in society.

Meanwhile, utilitarian philosophers have supported lies that achieve good outcomes – white lies.[37] In his 2008 book, How to Make Good Decisions and Be Right All the Time, Iain King suggested a credible rule on lying was possible, and he defined it as: "Deceive only if you can change behaviour in a way worth more than the trust you would lose, were the deception discovered (whether the deception actually is exposed or not)."[38]

In Lying, neuroscientist Sam Harris argues that lying is negative for the liar and the person who's being lied to. To say lies is to deny others access to reality, and often we cannot anticipate how harmful lies can be. The ones we lie to may fail to solve problems they could have solved only on a basis of good information. To lie also harms oneself, makes the liar distrust the person who's being lied to.[39] Liars generally feel badly about their lies and sense a loss of sincerity, authenticity, and integrity. Harris asserts that honesty allows one to have deeper relationships and to bring all dysfunction in one's life to the surface.

In Human, All Too Human, philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche suggested that those who refrain from lying may do so only because of the difficulty involved in maintaining lies. This is consistent with his general philosophy that divides (or ranks) people according to strength and ability; thus, some people tell the truth only out of weakness.

In other species

Possession of the capacity to lie among non-humans has been asserted during language studies with great apes. In one instance, the gorilla Koko, when asked who tore a sink from the wall, pointed to one of her handlers and then laughed.[40]

Deceptive body language, such as feints that mislead as to the intended direction of attack or flight, is observed in many species. A mother bird deceives when she pretends to have a broken wing to divert the attention of a perceived predator – including unwitting humans – from the eggs in her nest, instead to her, as she draws the predator away from the location of the nest, most notably a trait of the killdeer.[41]

In culture

Cultural references

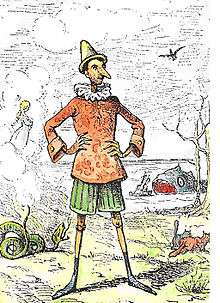

- Carlo Collodi's Pinocchio was a wooden puppet often led into trouble by his propensity to lie. His nose grew with every lie; hence, long noses have become a caricature of liars.

- Glenn Kessler, a journalist at The Washington Post, awards one to four Pinocchios to politicians in his Washington Post Fact Checker blog.[42]

- A famous anecdote by Parson Weems claims that George Washington once cut at a cherry tree with a hatchet when he was a small child. His father asked him who cut the cherry tree and Washington confessed his crime with the words: "I'm sorry, father, I cannot tell a lie."

- The Boy Who Cried Wolf, a fable attributed to Aesop about a boy who continually lies that a wolf is coming. When a wolf does appear, nobody believes him anymore.

- To Tell the Truth was the originator of a genre of game shows with three contestants claiming to be a person only one of them is.

The cliché "All is fair in love and war",[43][44] asserts justification for lies used to gain advantage in these situations. Sun Tzu declared that "All warfare is based on deception." Machiavelli advised in The Prince that a prince must hide his behaviors and become a "great liar and deceiver",[45] and Thomas Hobbes wrote in Leviathan: "In war, force and fraud are the two cardinal virtues."

Fiction

- The concept of a memory hole was first popularized by George Orwell's dystopian novel, Nineteen Eighty-Four, where the Party's Ministry of Truth systematically re-created all potential historical documents, in effect re-writing all of history to match the often-changing state propaganda. These changes were complete and undetectable.

- In the film Big Fat Liar, the story producer Marty Wolf (a notorious and proud liar) steals a story from student Jason Shepard, telling of a character whose lies become out of control to the point where each lie he tells causes him to grow in size.

- In the film Liar Liar, the lawyer Fletcher Reede (Jim Carrey) cannot lie for 24 hours, due to a wish of his son that magically came true.

- In the 1985 film Max Headroom, the title character comments that one can always tell when a politician lies because "their lips move". The joke has been widely repeated and rephrased.

- Larry-Boy! And the Fib from Outer Space! was a Veggie Tales story of a crime-fighting super-hero with super-suction ears, having to stop an alien, calling himself "Fib", from destroying the town of Bumblyburg due to the lies that caused Fib to grow. Telling the truth is the moral to this story.

- Lie to Me is a television series based on behavior analysts who read lies through facial expressions and body language. The protagonists, Dr. Cal Lightman and Dr. Gillian Foster are based on the above-mentioned Dr. Paul Ekman and Dr. Maureen O'Sullivan.

- The Invention of Lying is a 2009 movie depicting the fictitious invention of the first lie, starring Ricky Gervais, Jennifer Garner, Rob Lowe, and Tina Fey.

- The Adventures of Baron Munchausen tell the story about an eighteenth-century baron who tells outrageous, unbelievable stories, all of which he claims are true.

- In the games Grand Theft Auto IV and Grand Theft Auto V, there's an agency named FIB, a parody of the FBI, which is known to cover up stories, cooperate with criminals, and extract information with the use of lying.

Psychology

It is asserted that the capacity to lie is a talent human beings possess universally.[46]

The evolutionary theory proposed by Darwin states that only the fittest will survive and by lying, we aim to improve other's perception of our social image and status, capability, and desirability in general.[47] Studies have shown that humans begin lying at a mere age of six months, through crying and laughing, to gain attention.[48] Scientific studies have also shown the presence of gender differences in lying.

Although men and women lie at equal frequencies, men are more likely to lie in order to please themselves while women are more likely to lie to please others.[49] The presumption is that humans are individuals living in a world of competition and strict social norms, where they are able to use lies and deception to enhance chances of survival and reproduction.

Stereotypically speaking, Smith asserts that men like to exaggerate about their sexual expertise, but shy away from topics that degrade them while women understate their sexual expertise to make themselves more respectable and loyal in the eyes of men and avoid being labelled as a ‘scarlet woman’.[49]

Those with Parkinson's disease show difficulties in deceiving others, difficulties that link to prefrontal hypometabolism. This suggests a link between the capacity for dishonesty and integrity of prefrontal functioning.[50]

Pseudologia fantastica is a term applied by psychiatrists to the behavior of habitual or compulsive lying. Mythomania is the condition where there is an excessive or abnormal propensity for lying and exaggerating.[51]

A recent study found that composing a lie takes longer than telling the truth.[35] Or, as Chief Joseph succinctly put it, "It does not require many words to speak the truth."[52]

Some people believe that they are convincing liars, however in many cases, they are not.[53]

Religious perspectives

In the Bible

The Old Testament and New Testament of the Bible both contain statements that God cannot lie and that lying is immoral (Num. 23:19,[54] Hab. 2:3,[55] Heb. 6:13–18).[56] Nevertheless, there are examples of God deliberately causing enemies to become disorientated and confused, in order to provide victory (2 Thess. 2:11;[57][58] 1 Kings 22:23;[59] Ezek. 14:9).[60]

Various passages of the Bible feature exchanges that assert lying is immoral and wrong (Prov. 6:16–19; Ps. 5:6), (Lev. 19:11; Prov. 14:5; Prov. 30:6; Zeph. 3:13), (Isa. 28:15; Dan. 11:27), most famously, in the Ten Commandments: "Thou shalt not bear false witness" (Ex. 20:2–17; Deut. 5:6–21); Ex. 23:1; Matt. 19:18; Mark 10:19; Luke 18:20 a specific reference to perjury.

Other passages feature descriptive (not prescriptive) exchanges where lying was committed in extreme circumstances involving life and death, however, most Christian philosophers would argue that lying is never acceptable, but that even those who are righteous in God's eyes sin sometimes. Old Testament accounts of lying include:[61]

- The midwives lied about their inability to kill the Israelite children. (Ex. 1:15–21).

- Rahab lied to the king of Jericho about hiding the Hebrew spies (Josh. 2:4–5) and was not killed with those who were disobedient because of her faith (Heb. 11:31).

- Abraham instructed his wife, Sarah, to mislead the Egyptians and say that she is his sister (Gen. 12:10). Abraham's story was strictly true – Sarah was his half sister – but intentionally misleading because it was designed to lead the Egyptians to believe that Sarah was not Abraham's wife for Abraham feared that they would kill him in order to take her, for she was very beautiful.[62]

In the New Testament, Jesus refers to the Devil as the father of lies (John 8:44) and Paul commands Christians "Do not lie to one another" (Col. 3:9; cf. Lev. 19:11). In the Day of Judgement, unrepentant liars will be punished in the lake of fire. (Rev. 21:8; 21:27).

Augustine's taxonomy

Augustine of Hippo wrote two books about lying: On Lying (De Mendacio) and Against Lying (Contra Mendacio).[63][64] He describes each book in his later work, Retractions. Based on the location of De Mendacio in Retractions, it appears to have been written about AD 395. The first work, On Lying, begins: "Magna quæstio est de Mendacio" ("There is a great question about Lying"). From his text, it can be derived that St. Augustine divided lies into eight categories, listed in order of descending severity:

- Lies in religious teaching

- Lies that harm others and help no one

- Lies that harm others and help someone

- Lies told for the pleasure of lying

- Lies told to "please others in smooth discourse"

- Lies that harm no one and that help someone materially

- Lies that harm no one and that help someone spiritually

- Lies that harm no one and that protect someone from "bodily defilement"

Despite distinguishing between lies according to their external severity, Augustine maintains in both treatises that all lies, defined precisely as the external communication of what one does not hold to be internally true, are categorically sinful and therefore, ethically impermissible.[65]

Augustine wrote that lies told in jest, or by someone who believes or opines the lie to be true are not, in fact, lies.[66]

In Buddhism

The fourth of the five Buddhist precepts involves falsehood spoken or committed to by action.[67] Avoiding other forms of wrong speech are also considered part of this precept, consisting of malicious speech, harsh speech, and gossip.[68][69] A breach of the precept is considered more serious if the falsehood is motivated by an ulterior motive [67] (rather than, for example, "a small white lie").[70] The accompanying virtue is being honest and dependable,[71][72] and involves honesty in work, truthfulness to others, loyalty to superiors, and gratitude to benefactors.[73] In Buddhist texts, this precept is considered most important next to the first precept, because a lying person is regarded to have no shame, and therefore capable of many wrongs.[74] Lying is not only to be avoided because it harms others, but also because it goes against the Buddhist ideal of finding the truth.[70][75]

The fourth precept includes avoidance of lying and harmful speech.[76] Some modern Buddhist teachers such as Thich Nhat Hanh interpret this to include avoiding spreading false news and uncertain information.[74] Work that involves data manipulation, false advertising, or online scams can also be regarded as violations.[77] Anthropologist Barend Terwiel reports that among Thai Buddhists, the fourth precept also is seen to be broken when people insinuate, exaggerate, or speak abusively or deceitfully.[78]

In Norse paganism

In Gestaþáttr, one of the sections within the Eddaic poem Hávamál, Odin states that it is advisable, when dealing with "a false foe who lies", to tell lies also.[79]

In Zoroastrianism

Zoroaster teaches that there are two powers in the universe; Asha, which is truth, order, and that which is real, and Druj, which is "the Lie". Later on, the Lie became personified as Angra Mainyu, a figure similar to the Christian Devil, who was portrayed as the eternal opponent of Ahura Mazda (God).

Herodotus, in his mid-fifth-century BC account of Persian residents of the Pontus, reports that Persian youths, from their fifth year to their twentieth year, were instructed in three things – "to ride a horse, to draw a bow, and to speak the Truth".[80] He further notes that:[80] "The most disgraceful thing in the world [the Persians] think, is to tell a lie; the next worst, to owe a debt: because, among other reasons, the debtor is obliged to tell lies."

In Achaemenid Persia, the lie, drauga (in Avestan: druj), is considered to be a cardinal sin and it was punishable by death in some extreme cases. Tablets discovered by archaeologists in the 1930s [81] at the site of Persepolis give us adequate evidence about the love and veneration for the culture of truth during the Achaemenian period. These tablets contain the names of ordinary Persians, mainly traders and warehouse-keepers.[82] According to Stanley Insler of Yale University, as many as 72 names of officials and petty clerks found on these tablets contain the word truth.[83] Thus, says Insler, we have Artapana, protector of truth, Artakama, lover of truth, Artamanah, truth-minded, Artafarnah, possessing splendour of truth, Artazusta, delighting in truth, Artastuna, pillar of truth, Artafrida, prospering the truth, and Artahunara, having nobility of truth.

It was Darius the Great who laid down the "ordinance of good regulations" during his reign. Darius' testimony about his constant battle against the Lie is found in the Behistun Inscription. He testifies:[84] "I was not a lie-follower, I was not a doer of wrong ... According to righteousness I conducted myself. Neither to the weak or to the powerful did I do wrong. The man who cooperated with my house, him I rewarded well; who so did injury, him I punished well."

He asks Ahuramazda, God, to protect the country from "a (hostile) army, from famine, from the Lie".[85]

Darius had his hands full dealing with large-scale rebellion which broke out throughout the empire. After fighting successfully with nine traitors in a year, Darius records his battles against them for posterity and tells us how it was the Lie that made them rebel against the empire. At the Behistun inscription, Darius says: "I smote them and took prisoner nine kings. One was Gaumata by name, a Magian; he lied; thus he said: I am Smerdis, the son of Cyrus ... One, Acina by name, an Elamite; he lied; thus he said: I am king in Elam ... One, Nidintu-Bel by name, a Babylonian; he lied; thus he said: I am Nebuchadnezzar, the son of Nabonidus. ... The Lie made them rebellious, so that these men deceived the people."[86] Then advice to his son Xerxes, who is to succeed him as the great king: "Thou who shalt be king hereafter, protect yourself vigorously from the Lie; the man who shall be a lie-follower, him do thou punish well, if thus thou shall think. May my country be secure!"

See also

- Sophistry

- False analogy

- False equivalence

- Appeal to emotion

- Mutual deceit

- Plausible deniability

- Evasion (ethics)

- Weasel word

- No true Scotsman#Examples

- Post-truth politics

- Disinformation

- Black propaganda

- Fabrication (science)

- Betrayal

- Deception

- Propaganda

- Spin (public relations)

- Confabulation

- Ethics

- Falsifiability

- Honesty

- Mental reservation

- Prisoner's dilemma

- Psychological manipulation

- Traitor

- Truth

References

- Carson, Thomas L. (2012). Lying and deception : theory and practice. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199654802. OCLC 769544997.

- Mahon, James Edwin (2008-02-21). "The Definition of Lying and Deception". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 2019-03-18. Retrieved 2018-12-29.

- Mahon, James Edwin (2008). "Two Definitions of Lying". International Journal of Applied Philosophy. 22 (2): 211–230. doi:10.5840/ijap200822216. ISSN 0739-098X.

- Meibauer, Jörg, ed. (2018-11-15). The Oxford Handbook of Lying. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198736578.001.0001. ISBN 9780198736578.

- "Worldwidewords.org". Worldwidewords.org. 2009-06-13. Archived from the original on 2010-10-07. Retrieved 2013-07-10.

- Dictionary.com Archived 2018-04-21 at the Wayback Machine. 7 December 2017.

- Fu, Genyue; Evans, Angela D.; Wang, Lingfeng; Lee, Kang (July 2008). "Lying in the name of the collective good: a developmental study". Developmental Science. 11 (4): 495–503. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00695.x. PMC 2570108. PMID 18576957.

- On Bullshit. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2005. ISBN 0691122946. link Archived 2013-06-02 at the Wayback Machine

- Ericsson, Stephanie (2010). Patterns for College Writing (11th ed.). St. martins: Bedford. p. 487. ISBN 978-0312601522.

- AllCott, Hunt and Matthew Gentzkow. "Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election." Archived 2017-10-18 at the Wayback Machine Stanford University. Spring 2017. 7 December 2017.

- Druzin, Bryan (2011). "The Criminalization of Lying: Under what Circumstances, if any, should Lies be made Criminal?". Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology. 101: 548–50. Archived from the original on 2016-10-05. Retrieved 2016-10-05.

- "Merriam Webster Definition of Half-truth, August 1, 2007". M-w.com. 2012-08-31. Archived from the original on December 23, 2007. Retrieved 2013-07-10.

- Cavinder, Fred D. (1985). The Indiana Book of Records, Firsts, and Fascinating Facts. p. 104. ISBN 0253283205.

- Murphy, Kirk, Memorial Day Memory Hole: After Israel Forgets “Exodus”, White House Forgets “Shores of Tripoli”. Will Obama Remember NATO? Archived 2014-11-01 at the Wayback Machine 31 May 2010 Firedoglake.com

- Weinstein, Adam, Nevada Tea Partier's Memory Hole, 9 June 2010 Archived 31 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Mother Jones.

- Guerrero, L., Anderson, P., Afifi, W. (2007). Close Encounters: Communication in Relationships (2nd ed.). Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

- Minkler, Alanson (2011). Integrity and Agreement: Economics When Principles Also Matter. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. pp. 78, 128. ISBN 9780472116430.

- Arp, Robert (2013). Psych and Philosophy. Chicago: Open Court Publishing. p. 140. ISBN 9780812698251.

- Aruffo, Madeline. "Problems with the Noble Lie." *Archived 2017-05-17 at the Wayback Machine Boston University. Accessed 4 December 2017.

- Dike CC, Baranoski M, Griffith EE (2005). "Pathological lying revisited". The Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. 33 (3): 342–49. PMID 16186198. Archived from the original on 2013-01-13. Retrieved 2014-07-06.

- Dike, Charles C. (June 1, 2008). "Pathological Lying: Symptom or Disease?". 25 (7). Archived from the original on March 8, 2011. Retrieved July 6, 2014. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Butler Lie term coined at Cornell University". News.cornell.edu. 2010-12-20. Archived from the original on 2012-10-28. Retrieved 2013-07-10.

- Beatty, Jeffrey; Samuelson, Susan (2007-03-13). Cengage Advantage Books: Essentials of Business Law. p. 293. ISBN 978-0324537123.

- Niles' Register, June 13, 1829

- Transactions of the New York State Agricultural Society, Vol 19, 1859, p. 230.

- Microsoft Encarta, "weasel words Archived 2011-06-04 at the Wayback Machine"

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2020-04-18. Retrieved 2020-03-12.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2019-09-05. Retrieved 2020-03-12.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2019-10-28. Retrieved 2020-03-12.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Timasheff, Nicholas Sergeyevitch. "An Introduction to the Sociology of Law." Google Books. 7 December 2017.

- Arendt, Hannah. "Hannah Arendt: From an Interview." Archived 2017-12-01 at the Wayback Machine The New York Review of Books. 26 October 1978 issue. 30 November 2017.

- Zimmerman, Laura. "Deception detection." Archived 2017-12-08 at the Wayback Machine American Psychological Association. March 2016. 7 December 2017.

- Conti, Alli. "Are Lie Detector Tests Complete Bullshit?" Archived 2017-12-08 at the Wayback Machine VICE. 17 November 2014. 7 December 2017.

- Williams, Emma J.; Lewis A. Bott; John Patrick; Michael B. Lewis (April 3, 2013). "Telling Lies: The Irrepressible Truth?". PLOS ONE. 8 (4): e60713. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...860713W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0060713. PMC 3616109. PMID 23573277.

- Roy Britt, "Lies Take Longer Than Truths," LiveScience.com, January 26, 2009, found at Archived 2012-07-03 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed November 27, 2011.

- How to Make Good Decisions and Be Right All the Time, (2008), Iain King, p. 147.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-02-11. Retrieved 2012-07-10.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) | Sri Lanka's Sunday Observer article on lying, Feb 2012

- How to Make Good Decisions and Be Right All the Time, (2008), Iain King, p. 148.

- "Deceiver's Distrust: Denigration as a Consequence of Undiscovered Deception", (1998), Brad J. Sagarin, Kelton v. L. Rhoads, Robert B. Cialdini.

- Hanley, Elizabeth (4 July 2004). "Listening to Koko" (PDF). Commonweal Magazine: 16. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 7 July 2014.

- "Killdeer" Archived 2011-06-28 at the Wayback Machine. Ohio Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved 2011-3-1.

- "Guide to Washington Post Fact Checker Rating Scale". Voices.washingtonpost.com. December 29, 2011. Archived from the original on November 30, 2011. Retrieved January 3, 2012.

- 1620 T. Shelton tr. Cervantes' Don Quixote ii. xxi. Love and warre are all one. It is lawfull to use sleights and stratagems to attaine the wished end.

- 1578 Lyly Euphues I. 236 Anye impietie may lawfully be committed in loue, which is lawlesse.

- Machiavelli, Niccolo, The Prince, Chap. 18

- Bhattacharjee, Yudhijit. "Why We Lie: The Science Behind Our Deceptive Ways." Archived 2017-12-07 at the Wayback Machine National Geographic.

- "What is Darwin's Theory of Evolution?". LiveScience.com. Archived from the original on 2015-10-02. Retrieved 2015-10-12.

- "Why Do We Lie?". Psychology Today. Retrieved 2015-10-12.

- Smith, David Livingstone. "Natural-Born Liars".

- Abe, N.; Fujii, T.; Hirayama, K.; Takeda, A.; Hosokai, Y.; Ishioka, T.; Nishio, Y.; Suzuki, K.; Itoyama, Y.; Takahashi, S.; Fukuda, H.; Mori, E. (2009). "Do parkinsonian patients have trouble telling lies? The neurobiological basis of deceptive behaviour". Brain. 132 (5): 1386–95. doi:10.1093/brain/awp052. PMC 2677797. PMID 19339257.

- "Merriam–Webster.com". Merriam-webster.com. 2012-08-31. Archived from the original on 2010-02-19. Retrieved 2013-07-10.

- "People.tribe.net". People.tribe.net. 2007-08-19. Archived from the original on 2013-05-30. Retrieved 2013-07-10.

- Grieve, Rachel; Hayes, Jordana (2013-01-01). "Does perceived ability to deceive = ability to deceive? Predictive validity of the perceived ability to deceive (PATD) scale". Personality and Individual Differences. 54 (2): 311–14. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2012.09.001.

- "Num. 23:19". Biblegateway.com. Archived from the original on 2019-07-11. Retrieved 2013-07-10.

- "Hab. 2:3". Bible.cc. Archived from the original on 2011-08-14. Retrieved 2013-07-10.

- "Heb 6:13–18". Soundofgrace.com. 1996-11-10. Archived from the original on 2010-10-17. Retrieved 2013-07-10.

- "2 Thess. 2:11". Biblegateway.com. Archived from the original on 2018-11-23. Retrieved 2013-07-10.

- "2 Thess. 2:11". Biblegateway.com. Archived from the original on 2018-11-23. Retrieved 2013-07-10.

- "1 Kings 22:23". Bible.cc. Archived from the original on 2011-05-15. Retrieved 2013-07-10.

- "Ezek. 14:9". Bible.cc. Archived from the original on 2011-11-22. Retrieved 2013-07-10.

- See also: O'Neill, Barry. (2003). "A Formal System for Understanding Lies and Deceit." Archived 2008-02-28 at the Wayback Machine Revision of a talk for the Jerusalem Conference on Biblical Economics, June 2000.

- "Genesis 12:11 – "When he was about to enter Egypt, he said to Sarai his wife, 'I know that you are a woman'"". ESVBible.org. Retrieved 2013-07-10.

- Saint Augustine (2002). Deferrari, Roy J. (ed.). Treatises on various subjects. Translated by Mary Sarah Muldowney (1st pbk. reprint. ed.). New York: Catholic University of America Press. ISBN 978-0813213200. Archived from the original on 2017-02-03. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- Schaff, Philip (1887). A Select Library of the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church: St. Augustin: On the Holy Trinity. Doctrinal treatises. Moral treatises. The Christian Literature Company.

- "Church Fathers: On Lying (St. Augustine)". Archived from the original on 26 September 2010. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- Imre, Robert; Mooney, T. Brian; Clarke, Benjamin (2008). Responding to terrorism: political, philosophical and legal perspectives ([Online-Ausg.] ed.). Aldershot, Hampshire, England: Ashgate. ISBN 978-0754672777. Archived from the original on 2017-02-03. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- Leaman, Oliver (2000). Eastern Philosophy: Key Readings (PDF). Routledge. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-415-17357-5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 August 2017.

- Segall, Seth Robert (2003). "Psychotherapy Practice as Buddhist Practice". In Segall, Seth Robert (ed.). Encountering Buddhism: Western Psychology and Buddhist Teachings. State University of New York Press. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-7914-8679-5.

- Harvey 2000, pp. 74, 76.

- Harvey 2000, p. 75.

- Cozort, Daniel (2015). "Ethics". In Powers, John (ed.). The Buddhist World. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-42016-3.

- Harvey 2000, p. 68.

- Wai 2002, p. 3.

- Harvey 2000, p. 74.

- Wai 2002, p. 295.

- Powers, John (2013). A Concise Encyclopedia of Buddhism. Oneworld Publications. ISBN 978-1-78074-476-6.

- Johansen, Barry-Craig P.; Gopalakrishna, D. (21 July 2016). "A Buddhist View of Adult Learning in the Workplace". Advances in Developing Human Resources. 8 (3): 342. doi:10.1177/1523422306288426.

- Terwiel, Barend Jan (2012). Monks and Magic: Revisiting a Classic Study of Religious Ceremonies in Thailand (PDF). Nordic Institute of Asian Studies. p. 183. ISBN 9788776941017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 August 2018.

- "VTA.gamall-steinn.org". VTA.gamall-steinn.org. Archived from the original on 2005-09-12. Retrieved 2013-07-10.

- Herodotus (2009) [publication date]. The Histories. Translated by George Rawlinson. Digireads.Com. pp. 43–44. ISBN 978-1420933055.

- Garrison, Mark B.; Root, Margaret C. (2001). Seals on the Persepolis Fortification Tablets, Volume 1. Images of Heroic Encounter (OIP 117). Chicago: Online Oriental Institute Publications. Archived from the original on 5 January 2007. Retrieved 9 January 2007.

- Dandamayev, Muhammad (2002). "Persepolis Elamite Tablets". Encyclopedia Iranica. Archived from the original on 21 January 2012. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- Insler, Stanley (1975). "The Love of Truth in Ancient Iran". Archived from the original on 5 May 2007. Retrieved 9 January 2007. In Insler, Stanley; Duchesne-Guillemin, J. (ed.) (1975). The Gāthās of Zarathustra (Acta Iranica 8). Liege: Brill.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Brian Carr; Brian Carr; Indira Mahalingam (1997). Companino Encyclopedia of Asian philosophy. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0415035354.

- DPd inscription, lines 12–24: "Darius the King says: May Ahuramazda bear me aid, with the gods of the royal house; and may Ahuramazda protect this country from a (hostile) army, from famine, from the Lie! Upon this country may there not come an army, nor famine, nor the Lie; this I pray as a boon from Ahuramazda together with the gods of the royal house. This boon may Ahuramazda together with the gods of the royal house give to me! "

- "Darius, Behishtan (DB), Column 1". Archived from the original on 2017-07-19. Retrieved 2015-07-27. From Kent, Roland G. (1953). Old Persian: Grammar, texts, lexicon. New Haven: American Oriental Society.

Sources

- Harvey, Peter (2000), An Introduction to Buddhist Ethics: Foundations, Values and Issues (PDF), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-511-07584-1

- Wai, Maurice Nyunt (2002), Pañcasila and Catholic Moral Teaching: Moral Principles as Expression of Spiritual Experience in Theravada Buddhism and Christianity, Gregorian Biblical BookShop, ISBN 9788876529207

Further reading

- Adler, J.E. "Lying, deceiving, or falsely implicating," Journal of Philosophy, Vol. 94 (1997), 435–52.

- Aquinas, T., St. "Question 110: Lying," in Summa Theologiae (II.II), Vol. 41, Virtues of Justice in the Human Community (London, 1972).

- Augustine, St. "On Lying" and "Against Lying," in R.J. Deferrari, ed., Treatises on Various Subjects (New York, 1952).

- Bok, S. Lying: Moral Choice in Public and Private Life, 2d ed. (New York, 1989).

- Carson, Thomas L. (2006). "The Definition of Lying". Nous. 40 (2): 284–306. doi:10.1111/j.0029-4624.2006.00610.x.

- Chisholm, R.M.; Feehan, T.D. (1977). "The intent to deceive". Journal of Philosophy. 74 (3): 143–59. doi:10.2307/2025605. JSTOR 2025605.

- Davids, P.H.; Bruce, F.F.; Brauch, M.T. & W.C. Kaiser, Hard Sayings of the Bible (InterVarsity Press, 1996).

- Denery II, Dallas G. The Devil Wins: A History of Lying From the Garden of Eden to the Enlightenment (Princeton University Press; 2014) 352 pages; Uses religious, philosophical, literary and other sources in a study of lying from the perspectives of God, the Devil, theologians, courtiers, and women.

- Fallis, Don (2009). "What is Lying?". Journal of Philosophy. 106 (1): 29–56. doi:10.5840/jphil200910612. SSRN 1601034.

- Frankfurt, H.G. "The Faintest Passion," in Necessity, Volition and Love (Cambridge, MA: CUP, 1999).

- Frankfurt, Harry, On Bullshit (Princeton University Press, 2005).

- Hausman, Carl, "Lies We Live By," (New York: Routledge, 2000).

- Kant, I. Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals, The Metaphysics of Morals and "On a supposed right to lie from philanthropy," in Immanuel Kant, Practical Philosophy, eds. Mary Gregor and Allen W. Wood (Cambridge: CUP, 1986).

- Lakoff, George, Don't Think of an Elephant, (Chelsea Green Publishing, 2004).

- Leslie I. Born Liars: Why We Can't Live Without Deceit (2011)

- Mahon, J.E. "Kant on Lies, Candour and Reticence," Kantian Review, Vol. 7 (2003), 101–33.

- Mahon, J.E. "Two Definitions of Lying," International Journal of Applied Philosophy, Vol. 22, Issue 2 (2008), 211–30

- Mahon, J.E. (2008; rev. 2015). "The Definition of Lying and Deception," Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Mahon, J.E., "Lying," Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2nd ed., Vol. 5 (Farmington Hills, MI: Macmillan Reference, 2006), 618–19.

- Mahon, J.E. "Kant and the Perfect Duty to Others Not to Lie," British Journal for the History of Philosophy, Vol. 14, No. 4 (2006), 653–85.

- Mahon, J.E. "Kant and Maria von Herbert: Reticence vs. Deception," Philosophy, Vol. 81, No. 3 (2006), 417–44.

- Mannison, D.S. "Lying and Lies," Australasian Journal of Philosophy, Vol. 47 (1969), 132–44.

- O'Neill, Barry. (2003). "A Formal System for Understanding Lies and Deceit." Revision of a talk for the Jerusalem Conference on Biblical Economics, June 2000.

- Siegler, F.A. "Lying," American Philosophical Quarterly, Vol. 3 (1966), 128–36.

- Sorensen, Roy (2007). "Bald-Faced Lies! Lying Without the Intent to Deceive". Pacific Philosophical Quarterly. 88 (2): 251–64. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0114.2007.00290.x.

- Stokke, Andreas (2013). "Lying and Asserting". Journal of Philosophy. 110 (1): 33–60. doi:10.5840/jphil2013110144. SSRN 1601034.

- Margaret Talbot (2007). "Duped. Can brain scans uncover lies?". The New Yorker, July 2, 2007.

External links

| Look up liar in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Look up lie in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Lie |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lies. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1920 Encyclopedia Americana article Lie. |