Mexican Drug War

The Mexican Drug War (also known as the Mexican War on Drugs; Spanish: Guerra contra el narcotráfico en México)[24] is the Mexican theater of the global war on drugs, as led by the U.S. federal government, that has resulted in an ongoing asymmetric[25][26] low-intensity conflict between the Mexican government and various drug trafficking syndicates. When the Mexican military began to intervene in 2006, the government's principal goal was to reduce drug-related violence.[27] The Mexican government has asserted that their primary focus is on dismantling the powerful drug cartels, and on preventing drug trafficking demand along with the U.S. functionaries.[28][29]

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Mexico |

|

|

Spanish rule |

|

| Timeline |

|

|

Violence escalated soon after the arrest of Miguel Ángel Félix Gallardo in 1989 the leader and the founder of the first Mexican drug cartel, the Guadalajara Cartel. The Guadalajara Cartel was an alliance of the current existing cartels (which included the Sinaloa Cartel, the Juarez Cartel, the Tijuana Cartel, the Gulf Cartel and the Sonora Cartel) headed by Félix Gallardo. Due to his arrest, the alliance broke and certain high-ranking members formed their own cartels and each of them fought for control of territory and trafficking routes.

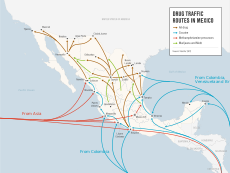

Although Mexican drug trafficking organizations have existed for several decades, their influence increased[30][31] after the demise of the Colombian Cali and Medellín cartels in the 1990s. Mexican drug cartels now dominate the wholesale illicit drug market and in 2007 controlled 90% of the cocaine entering the United States.[32][33] Arrests of key cartel leaders, particularly in the Tijuana and Gulf cartels, have led to increasing drug violence as cartels fight for control of the trafficking routes into the United States.[34][35][36]

Federal law enforcement has been reorganized at least five times since 1982 in various attempts to control corruption and reduce cartel violence. During that same period, there have been at least four elite special forces created as new, corruption-free soldiers who could do battle with Mexico's endemic bribery system.[37] Analysts estimate that wholesale earnings from illicit drug sales range from $13.6 to $49.4 billion annually.[32][38][39] The U.S. Congress passed legislation in late June 2008 to provide Mexico with US$1.6 billion for the Mérida Initiative as well as technical advice to strengthen the national justice systems. By the end of President Felipe Calderón's administration (December 1, 2006 – November 30, 2012), the official death toll of the Mexican Drug War was at least 60,000.[40] Estimates set the death toll above 120,000 killed by 2013, not including 27,000 missing.[41][42] Since taking office in 2018, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador declared that the war was over; however, his comment was met with criticism as the homicide rate remains high.

Background

Due to its location, Mexico has long been used as a staging and transhipment point for narcotics and contraband between Latin America and U.S. markets. Mexican bootleggers supplied alcohol to the United States gangsters throughout the duration of the Prohibition in the United States,[33] and the onset of the illegal drug trade with the U.S. began when the prohibition came to an end in 1933.[33] Towards the end of the 1960s, Mexican narcotic smugglers started to smuggle drugs on a major scale.[33]

During the 1970s and early 1980s, Colombia's Pablo Escobar was the main exporter of cocaine and dealt with organized criminal networks all over the world. While Escobar's Medellin Cartel and the Cali Cartel would manufacture the products, Miguel Ángel Félix Gallardo's Guadalajara Cartel would oversee distribution. When enforcement efforts intensified in South Florida and the Caribbean, the Colombian organizations formed partnerships with the Mexico-based traffickers to transport cocaine by land through Mexico into the United States.[43]

This was easily accomplished because Mexico had long been a major source of heroin and cannabis, and drug traffickers from Mexico had already established an infrastructure that stood ready to serve the Colombia-based traffickers. By the mid-1980s, the organizations from Mexico were well-established and reliable transporters of Colombian cocaine. At first, the Mexican gangs were paid in cash for their transportation services, but in the late 1980s, the Mexican transport organizations and the Colombian drug traffickers settled on a payment-in-product arrangement.[44]

Transporters from Mexico usually were given 35% to 50% of each cocaine shipment. This arrangement meant that organizations from Mexico became involved in the distribution, as well as the transportation of cocaine, and became formidable traffickers in their own right. In recent years, the Sinaloa Cartel and the Gulf Cartel have taken over trafficking cocaine from Colombia to the worldwide markets.[44]

The balance of power between the various Mexican cartels continually shifts as new organizations emerge and older ones weaken and collapse. A disruption in the system, such as the arrests or deaths of cartel leaders, generates bloodshed as rivals move in to exploit the power vacuum.[45] Leadership vacuums are sometimes created by law enforcement successes against a particular cartel, so cartels often will attempt to pit law enforcement against one another, either by bribing corrupt officials to take action against a rival or by leaking intelligence about a rival's operations to the Mexican or U.S. government's Drug Enforcement Administration.[45]

While many factors have contributed to the escalating violence, security analysts in Mexico City trace the origins of the rising scourge to the unraveling of a longtime implicit arrangement between narcotics traffickers and governments controlled by the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), which began to lose its grip on political power in the late 1980s.[46]

The fighting between rival drug cartels began in earnest after the 1989 arrest of Félix Gallardo, who ran the cocaine business in Mexico.[47] There was a lull in the fighting during the late 1990s but the violence has steadily worsened since 2000.

Presidents

The dominant party PRI ruled Mexico for around 70 years until 2000. During this time, drug cartels expanded their power and corruption, and anti-drug operations focused mainly on destroying marijuana and opium crops in mountainous regions. There were no large-scale high-profile military operations against their core structures in urban areas until the 2000 Mexican election, when the right-wing PAN party gained the presidency and started a crackdown on cartels in their own turf.

Vicente Fox

In the year 2000 Vicente Fox, from the right-wing PAN party, became the first Mexican president not to be from the PRI party (that ruled Mexico for 70 years); his presidency passed with relative peace, having a crime index not too different from that of previous administrations, and Mexican public opinion was mainly optimistic with the regime change, with Mexico even showing a general decline in homicide rates from 2000 to 2007.[48] One of the Fox's administration's strongest criticisms arose from its management of the peasant unrest in San Salvador Atenco.

During this time, the Mexican criminal underworld was not widely known, as it later became with president Calderon and his War on Drugs. Key components of the upcoming conflict started to occur, like the Sinaloa Cartel attacks and advance on the Gulf Cartel's main turf in Tamaulipas.

It is estimated that in the first 8 months of 2005 (between January and August) about 110 people died in Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas as a result of the fighting between the Gulf and Sinaloa cartels.[49] The same year, there was another surge in violence in the state of Michoacán as the La Familia Michoacana drug cartel established itself, after splintering from its former allies, the Gulf Cartel and Los Zetas.

Felipe Calderón

On December 11, 2006, the newly elected President Felipe Calderón, from the right wing PAN party, dispatched 6,500 Mexican Army soldiers to Michoacán, his home state, to end drug violence there. This action is regarded as the first major retaliation made against the cartel violence, and is generally viewed as the starting point of the Mexican Drug War between the government and the drug cartels.[50] As time passed, Calderón continued to escalate his anti-drug campaign, in which there are now about 45,000 troops involved along with state and federal police forces.[51]

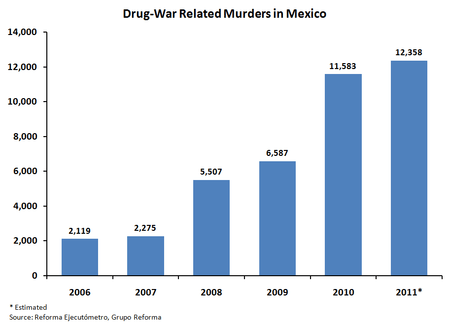

The government was relatively successful in detaining drug lords; however, drug-related violence spiked high in contested area along the U.S. border such as Ciudad Juárez, Tijuana, and Matamoros. Some analysts, like U.S. Ambassador in Mexico Carlos Pascual, argued that this rise in violence was a direct result of Felipe Calderón's military measures.[52] Since Calderón launched his military strategy against organized crime, there was an alarming increase in violent deaths related to organized crime: more than 15,000 people died in suspected drug cartel attacks since it was launched at the end of 2006.[52] More than 5,000 people were murdered in Mexico in 2008,[53] followed by 9600 murders in 2009, 2010 was violent, with over 15,000 homicides across the country.[54]

By the end of Calderón's presidency his administration statistics claimed that, during his 6-year term, 50,000 drug related homicides occurred,[55] however later revelations showed that more than 120,000 murders happened as result of his militaristic anti-drug policy.[56]

Enrique Peña Nieto

In 2012, newly elected president Enrique Peña Nieto, from the PRI party, emphasized that he did not support the involvement of armed American agents in Mexico, being only interested in military training of Mexican forces in counter-insurgency tactics.[57] Peña stated that he planned to deescalate the conflict, focusing in lowering criminal violence rates, as opposed to the previous policy of attacking drug-trafficking organizations by arresting or killing the most-wanted drug lords and intercepting their drug shipments.[58]

However, in the first 14 months of his administration, between December 2012 and January 2014, 23,640 people died in the conflict.[59]

In 2013 Mexico saw the rise of the controversial Grupos de Autodefensa Comunitaria (self-defence groups) in southern Mexico, para-military groups led by land-owners, ranchers and other rural businessmen that took up arms against the criminal groups that wanted to impose dominance in their towns, entering a new phase in the Mexican war on drugs.[60] However this strategy, allegedly proposed by General Óscar Naranjo, Peña's security advisor from Colombia,[61] crumbled when autodefensas started to have internal organization struggles and disagreements with the government, being finally infiltrated by criminal elements, that deprived the government forces the ability to distinguish between armed-civilian convoys and drug-cartel convoys, forcing Peña's administration to distance from them.[62]

Peña's handling of the 2014 Iguala mass kidnapping and the 2015 escape of drug lord "El Chapo" Guzmán from the Altiplano maximum security prison sparked international criticism.[63][64]

A great part of Peña Nieto's strategy consisted in making the Mexican Interior Ministry solely responsible for public security and the creation of a national military level police force called the National Gendarmerie. In December 2017, the Law of Internal Security was passed by legislation but was met with criticism, especially from the National Human Rights Commission, accusing it gave the President a blank check.[65][66][67][68]

Andrés Manuel López Obrador

Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), the President from the centre-left National Regeneration Movement party, took office on December 1, 2018. One of his campaign promises was a controversial "strategy for peace", that is to give amnesty to all Mexicans involved in drug production and trafficking as a way to stop the drug trade and the resulting turf violence.[69] His proposed amnesty is still ill-defined.[69] His aides explained that the plan was not to pardon real criminals, like violent drug cartel members, but to prevent other people from following that path, especially low-income people, poor farmers, and young people that may end up in jail for drug possession.[70] President López Obrador points out that the past approaches failed because they were based on misunderstanding the core problem. According to him, the underlying issue is Mexico's great social disparities which previous governments' economic policies did not reduce.

For law enforcement, he promised to hold a referendum for the creation of a temporary national guard, merging elite parts of the Federal police, Military police, Navy, Chief of Staff's Guard and other top Mexican Security agencies, intending to finally give a legal framework to the military grade forces that have been doing police work in the last years.[71] He promised not to use arms to suppress the people, and made an announcement to free political prisoners. His approach is to pay more attention to the victims of violent crime and he wants to revisit two previously taken strategies.[72] In 2019, the promised Mexican National Guard was created.[73]

Despite the new government's planned strategy changes,[74] during the first two months of the new presidency the violence between drug trafficking organizations sustained the same levels as previous years.[75]

However, on January 30, 2019, President López Obrador declared the end of the Mexican war on drugs.[76][77] the President stated that he will now focus on reducing spending,[78] and direct its military and police efforts primarily on stopping the armed gasoline theft rings —locally called huachicoleros— that have been stealing more than 70 thousand barrels of oil, diesel and gasoline daily,[79][80][81] costing the Mexican economy around 3 billion dollars every year.[82]

On October 17, 2019, based on an extradition request sent to Mexico by a Washington DC judge[83] and misinformation provided to Mexican authorities,[84] a failed operation to capture alleged kingpin Ovidio Guzmán López was carried by the Mexican National Guard, in which fourteen people died (mostly from the armed forces and cartel enforcers, and one civilian bystander).[85] Guzmán was released[86] after approximately 700 cartel enforcers,[87] armed with 50 caliber rifles, RPGs and 40 mm grenades took multiple hostages, including the housing unit where military families live in Culiacan.[88] The cartels used burning vehicles to block roads, a tactic taken from militant protesters, with the event described as a mass insurrection.[89] AMLO defended the decision to release Ovidio Guzmán, arguing it prevented further loss of life,[90] and insisted that he wants to avoid more massacres.[91] He further stated that the capture of one drug smuggler cannot be more valuable than the lives of innocent civilians,[92] and that even though they underestimated the cartel's manpower and ability to respond[93] the criminal process against Ovidio is still ongoing,[94] The federal forces have since deployed 8,000 troops and police reinforcements to restore peace in Culiacan.[87]

This strategy of avoiding armed confrontations while drug organizations still have violent altercations has risen controversy.[95][75][96][97] One of the strongest critics of the new strategy and a firm proponent of continuing the armed struggle is former President Felipe Calderón, who originally started the military operations against traffickers a decade ago (in 2006),[98][99] and whose failed armed strategy to stop cartel violence was also criticised by local and foreign experts, as well as by multiple media outlets.[100][101][102]

Drug sources and use

Sources

Mexico is a major drug transit and producing country. It is the main foreign supplier of cannabis and an important entry point of South American cocaine[103] and Asian[104] methamphetamine to the United States.[32] It is believed that almost half the cartels' revenues come from cannabis.[105] Cocaine, heroin, and increasingly methamphetamine are also traded.[106]

The U.S. State Department estimates that 90 percent of cocaine entering the United States is produced in Colombia[107] (followed by Bolivia and Peru)[108] and that the main transit route is through Mexico.[32] Drug cartels in Mexico control approximately 70% of the foreign narcotics flow into the United States.[109]

Although Mexico accounts for only a small share of worldwide heroin production, it supplies a large share of the heroin distributed in the United States.[110]

Since 2003 Mexican cartels have used the dense, isolated portions of U.S. federal and state parks and forests to grow marijuana under the canopy of thick trees. Billions of dollars’ worth of marijuana has been produced annually on U.S. soil. "In 2006, federal and state authorities seized over 550,000 marijuana plants worth an estimated 1 billion dollars in Kentucky’s remote Appalachian counties". Cartels profited from marijuana growing operations from Arkansas to Hawaii.[111]

A 2018 study found that the reduction in drugs from Colombia contributed to Mexican drug violence. The study estimated, "between 2006 and 2009 the decline in cocaine supply from Colombia could account for 10%–14% of the increase in violence in Mexico."[112]

Use

The prevalence of illicit drug use in Mexico is still low compared to the United States;[113] however, with the increased role of Mexico in the trafficking and production of illicit drugs, the availability of drugs has slowly increased locally since the 1980s.[113] In the decades before this period, consumption was not generalized – reportedly occurring mainly among persons of high socioeconomic status, intellectuals and artists.[113]

As the United States of America is the world's largest consumer of cocaine,[114] as well as of other illegal drugs,[115] their demand is what motivates the drug business, and the main goal of Mexican cartels is to introduce narcotics into the U.S.

The export rate of cocaine to the U.S. has decreased following stricter border control measures in response to the September 11 attacks.[113][116]

This has led to a surplus of cocaine which has resulted in local Mexican dealers attempting to offload extra narcotics along trafficking routes, especially in border areas popular among low income North American tourists.

Drug shipments are often delayed in Mexican border towns before delivery to the U.S., which has forced drug traffickers to increase prices to account for transportation costs of products across international borders, making it a more profitable business for the drug lords, and has likely contributed to the increased rates of local drug consumption.[113]

With increased cocaine use, there has been a parallel rise in demand for drug user treatment in Mexico.[113]

Poverty

One of the main factors driving the Mexican Drug War is the willingness of mainly lower-class people to earn easy money joining criminal organizations, and the failure of the government to provide the legal means for the creation of well paid jobs. From 2004 to 2008 the portion of the population who received less than half of the median income rose from 17% to 21% and the proportion of population living in extreme or moderate poverty rose from 35 to 46% (52 million persons) between 2006 and 2010.[117][118][119]

Among the OECD countries, Mexico has the second highest degree of economic disparity between the extremely poor and extremely rich.[120] The bottom ten percent in the income hierarchy disposes of 1.36% of the country's resources, whereas the upper ten percent dispose of almost 36%. OECD also notes that Mexico's budgeted expenses for poverty alleviation and social development is only about a third of the OECD average.[118]

In 2012 it was estimated that Mexican cartels employed over 450,000 people directly and a further 3.2 million people's livelihoods depended on various parts of the drug trade.[121] In cities such as Ciudad Juárez, up to 60% of the economy depended on illegitimate money making.[122]

Education

A problem that goes hand in hand with poverty in Mexico is the level of schooling.[123][124] In the 1960s, when Mexican narcotic smugglers started to smuggle drugs on a major scale,[33] only 5.6% of the Mexican population had education beyond the six years of basic school.[125]

More recently, researchers from the World Economic Forum have noted that despite the Mexican economy being ranked 31st out of 134 economies for investment in education (5.3% of its GDP), as of 2009, the nation's primary education system is only ranked 116th, thereby suggesting "that the problem is not how much but rather how resources are invested".[126] The WEF further explained: "The powerful teachers union, the SNTE, the largest labor union in Latin America, has been in large part responsible for blocking reforms that would increase the quality of spending and help ensure equal access to education." The result of the high levels of poverty, lack of well paid jobs, government corruption, and the systemic failure of Mexico's schools has been the appearance of los ninis, an youth underclass of school-dropouts who neither work nor study, whom might ended up as combatants on behalf of the cartels.[127]

However, teachers unions argue that they oppose reforms that propose teachers being tested and graded on their students' performance[128] with universally standard exams that do not take into account the socioeconomic differences between middle class urban schools and under-equipped poor rural schools, which has an important effect on the students performance.[129][130][131][132] Also, teachers argue that the legislation is ambiguous, only focus on the teachers, without touching the Education Ministry, and will allow more abuses and more political corruption.[133][134][135][136][137]

Mexican cartels

The Origin and Birth

The birth of most Mexican drug cartels is traced to former Mexican Judicial Federal Police agent Miguel Ángel Félix Gallardo (Spanish: El Padrino, lit. 'The Godfather'), who founded the Guadalajara Cartel in 1980 and controlled most of the illegal drug trade in Mexico and the trafficking corridors across the Mexico–U.S. border along with Juan García Ábrego throughout the 1980s.[138] He started off by smuggling marijuana and opium into the U.S., and was the first Mexican drug chief to link up with Colombia's cocaine cartels in the 1980s. Through his connections, Félix Gallardo became the person at the forefront of the Medellín Cartel, which was run by Pablo Escobar.[139] This was easily accomplished because Gallardo had already established a marijuana trafficking infrastructure that stood ready to serve the Colombia-based cocaine traffickers.

There were no other cartels at that time in Mexico.[139]:41 Félix Gallardo was the lord of Mexican drug smugglers.[139] He oversaw all operations; there was just him, his cronies, and the politicians who sold him protection.[139] However, the Guadalajara Cartel suffered a major blow in 1985 when the group's co-founder Rafael Caro Quintero was captured, and later convicted, for the murder of DEA agent Enrique Camarena.[140][141] Félix Gallardo afterwards kept a low profile and in 1987 he moved with his family to Guadalajara. According to Peter Dale Scott, the Guadalajara Cartel prospered largely because it enjoyed the protection of the Dirección Federal de Seguridad (DFS), under its chief Miguel Nazar Haro.[142]

Félix Gallardo was arrested on April 8, 1989.[143] He then decided to divide up the trade he controlled as it would be more efficient and less likely to be brought down in one law enforcement swoop.[139]:47 In a way, he was privatizing the Mexican drug business while sending it back underground, to be run by bosses who were less well known or not yet known by the DEA. Gallardo sent his lawyer to convene the nation's top drug traffickers at a house in Acapulco where he designated the plazas or territories.[139][144]

The Tijuana route would go to his nephews the Arellano Felix brothers. The Ciudad Juárez route would go to the Carrillo Fuentes family. Miguel Caro Quintero would run the Sonora corridor. Meanwhile, Joaquín Guzmán Loera and Ismael Zambada García would take over Pacific coast operations, becoming the Sinaloa Cartel. Guzmán and Zambada brought veteran Héctor Luis Palma Salazar back into the fold. The control of the Matamoros, Tamaulipas corridor—then becoming the Gulf Cartel—would be left undisturbed to its founder Juan García Ábrego, who was not a party to the 1989 pact.[145]

Félix Gallardo still planned to oversee national operations, as he maintained important connections, but he would no longer control all details of the business.[139] When he was transferred to a high-security prison in 1993, he lost any remaining control over the other drug lords.[146]

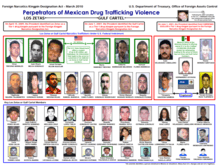

Major cartels in the war

Sinaloa Cartel

The Sinaloa Cartel began to contest the Gulf Cartel's domination of the coveted southwest Texas corridor following the arrest of Gulf Cartel leader Osiel Cárdenas in March 2003. The "Federation" was the result of a 2006 accord between several groups located in the Pacific state of Sinaloa. The cartel was led by Joaquín "El Chapo" Guzmán, who was Mexico's most-wanted drug trafficker with an estimated net worth of U.S. $1 billion. This made him the 1140th richest man in the world and the 55th most powerful, according to his Forbes magazine profile.[147] He was arrested and escaped in July 2015,[148][149] and re-arrested in January 2016.[150] In February 2010, new alliances were formed against Los Zetas and Beltrán-Leyva Cartel.[151]

The Sinaloa Cartel fought the Juárez Cartel in a long and bloody battle for control over drug trafficking routes in and around the northern city of Ciudad Juárez. The battle eventually resulted in defeat for the Juárez Cartel but not before taking the lives of between 5,000 and 12,000 people.[152] During the war for the turf in Ciudad Juárez the Sinaloa Cartel used several gangs (e.g. Los Mexicles, the Artistas Asesinos and Gente Nueva) to attack the Juárez Cartel.[152] The Juárez Cartel similarly used gangs such as La Línea and the Barrio Azteca to fight the Sinaloa Cartel.[152]

As of May 2010, numerous reports by Mexican and U.S. media stated that Sinaloa had infiltrated the Mexican federal government and military, and colluded with it to destroy the other cartels.[153][154] The Colima, Sonora and Milenio Cartels are now branches of the Sinaloa Cartel.[155]

Joaquín "El Chapo" Guzmán was arrested on January 8, 2016, and extradited to the United States a year later. On February 4, 2019, in Brooklyn, NY, he was found guilty of ten counts of drug trafficking and sentenced to life imprisonment. Guzman's defense was that he was simply a fall-guy for Ismael "El Mayo" Zambada, but prosecutors did not buy that.[156] "El Chapo" alleged that he had paid former presidents Enrique Peña Nieto and Felipe Calderón bribes, which was quickly denied by both men.[157] In March 2019, El Chapo's successor, Ismael Zambada García, alias “El Mayo,” was reported to be Mexico's "last Capo" and even more feared than his closest rival Nemesio Oseguera Cervantes, alias “El Mencho,” who serves as leader of the Jalisco Cartel New Generation.[158]

Beltrán-Leyva Cartel

The Beltrán-Leyva Cartel was a Mexican drug cartel and organized crime syndicate founded by the four Beltrán Leyva brothers: Marcos Arturo, Carlos, Alfredo and Héctor.[159][160][161][162] In 2004 and 2005, Arturo Beltrán Leyva led powerful groups of assassins to fight for trade routes in northeastern Mexico for the Sinaloa Cartel. Through the use of corruption or intimidation, the Beltrán-Leyva Cartel was able to infiltrate Mexico's political,[163] judicial[164] and police institutions to feed classified information about anti-drug operations,[165][166] and even infiltrated the Interpol office in Mexico.[167]

Following the December 2009 death of the cartel's leader Arturo Beltrán Leyva by Mexican Marines the cartel entered into an internal power struggle between Arturo's brother, Héctor Beltrán Leyva, and Arturo's top enforcer Edgar Valdez Villarreal.[8] Meanwhile, the cartel continued to dissolve with factions such as the South Pacific Cartel, La Mano Con Ojos, Independent Cartel of Acapulco, and La Barredora forming and the latter two cartels starting yet another intra-Beltrán Leyva Cartel conflict.[8]

The Mexican Federal Police considers the cartel to have been disbanded,[168][169] and the last cartel leader, Héctor Beltrán Leyva, was captured in October 2014.[170]

Juárez Cartel

The Juárez Cartel controls one of the primary transportation routes for billions of dollars' worth of illegal drug shipments annually entering the United States from Mexico.[171] Since 2007, the Juárez Cartel has been locked in a vicious battle with its former partner, the Sinaloa Cartel, for control of Ciudad Juárez. La Línea is a group of Mexican drug traffickers and corrupt Juárez and Chihuahua state police officers who work as the armed wing of the Juárez Cartel.[172] Vicente Carrillo Fuentes headed the Juárez Cartel until his arrest in 2014.

Since 2011, the Juárez Cartel continues to weaken;[173][174] however, holds presence in the three main points of entry into El Paso, Texas. The Juárez Cartel is only a shadow of the organization it was a decade ago, and its weakness and inability to effectively fight against Sinaloa's advances in Juarez contributed to the lower death toll in Juarez in 2011.[175]

Tijuana Cartel

The Tijuana Cartel, also known as the Arellano Félix Organization, was once among Mexico's most powerful.[176] It is based in Tijuana, one of the most strategically important border towns in Mexico,[177] and continues to export drugs even after being weakened by an internal war in 2009. Due to infighting, arrests and the deaths of some of its top members, the Tijuana Cartel is a fraction of what it was in the 1990s and early 2000s, when it was considered one of the most potent and violent criminal organizations in Mexico by the police. After the arrest or assassination of various members of the Arellano Félix clan, the cartel is currently headed by Luis Fernando Sánchez Arellano, a nephew of the Arellano Félix brothers.

Gulf Cartel

The Gulf Cartel (Cartel del Golfo), based in Matamoros, Tamaulipas, has been one of Mexico's two dominant cartels in recent years. In the late 1990s, it hired a private mercenary army (an enforcer group now called Los Zetas), which in 2006 stepped up as a partner but, in February 2010, their partnership was dissolved and both groups engaged in widespread violence across several border cities of Tamaulipas state,[151][178] turning several border towns into "ghost towns".[179]

The Gulf Cartel (CDG) was strong at the beginning of 2011, holding off several Zetas incursions into its territory. However, as the year progressed, internal divisions led to intra-cartel battles in Matamoros and Reynosa, Tamaulipas state. The infighting resulted in several arrests and deaths in Mexico and in the United States. The CDG has since broken apart, and it appears that one faction, known as Los Metros, has overpowered its rival Los Rojos faction and is now asserting its control over CDG operations.[180]

The infighting has weakened the CDG, but the group seems to have maintained control of its primary plazas, or smuggling corridors, into the United States.[180] The Mexican federal government has made notable successes in capturing the leadership of the Gulf Cartel. Osiel Cárdenas Guillén, his brothers Antonio Cárdenas Guillén, Mario Cárdenas Guillén, and Jorge Eduardo Costilla Sánchez have all been captured and incarcerated during Felipe Calderón's administration.

Los Zetas

In 1999, Gulf Cartel's leader, Osiel Cárdenas Guillén, hired a group of 37 corrupt former elite military soldiers to work for him. These former Airmobile Special Forces Group (GAFE), and Amphibian Group of Special Forces (GANFE) soldiers became known as Los Zetas and began operating as a private army for the Gulf Cartel. During the early 2000s the Zetas were instrumental in the Gulf Cartel's domination of the drug trade in much of Mexico.

After the 2007 arrest and extradition of Osiel Cárdenas Guillén, the Zetas seized the opportunity to strike out on their own. Under the leadership of Heriberto Lazcano, the Zetas, numbering about 300, gradually set up their own independent drug, arms and human-trafficking networks.[181] In 2008, Los Zetas made a deal with ex-Sinaloa cartel commanders, the Beltrán-Leyva brothers and since then, became rivals of their former employer/partner, the Gulf Cartel.[151][182]

In early 2010 the Zetas made public their split from the Gulf Cartel and began a bloody war with Gulf Cartel over control of northeast Mexico's drug trade routes.[8] This war has resulted in the deaths of thousands of cartel members and suspected members. Furthermore, due to alliance structures, the Gulf Cartel-Los Zetas conflict drew in other cartels, namely the Sinaloa Cartel which fought the Zetas in 2010 and 2011.[8]

The Zetas are notorious for targeting civilians, including the mass murder of 72 migrants in the San Fernando massacre.[8]

The Zetas involved themselves in more than drug trafficking and have also been connected to human trafficking, pipeline trafficked oil theft, extortion, and trading unlicensed CDs.[8] Their criminal network is said to reach far from Mexico including into Central America, the U.S. and Europe.[8]

On 15 July 2013, the Mexican Navy arrested the top Zeta boss Miguel Treviño Morales.[183]

In recent times, Los Zetas have experienced severe fragmentation and seen its influence diminish.[184] As of December 2016, two subgroups calling themselves Los Zetas Grupo Bravo (Group Bravo) and Zetas Vieja Escuela (Old School Zetas) formed an alliance with the Gulf Cartel against a group known as El Cartel del Noreste (The Cartel of the Northeast).[185]

La Familia Cartel

La Familia Michoacana was a major Mexican drug cartel based in Michoacán between at least 2006 and 2011. It was formerly allied to the Gulf Cartel and Los Zetas, but split off and became an independent organization.[186]

In 2009–10, a counter-narcotics offensive by Mexican and U.S. government agencies produced the arrest of at least 345 suspected La Familia members in the U.S., and the incorrectly presumed death[189] of one of the cartel's founders, Nazario Moreno González, on December 9, 2010.[8] The cartel then divided into the Knights Templar Cartel and a José de Jesús Méndez Vargas-led faction, which kept the name La Familia. Following the cartel's fragmentation in late 2010 and early 2011, the La Familia Cartel under Méndez Vargas fought the Knights Templar Cartel but on June 21, 2011 Méndez Vargas was arrested by Mexican authorities[8] and in mid-2011 the attorney general in Mexico (PGR) stated that La Familia Cartel had been "exterminated",[190] leaving only the splinter group, the Knights Templar Cartel.[191][192]

In February 2010, La Familia forged an alliance with the Gulf Cartel against Los Zetas and Beltrán-Leyva Cartel.[151]

Knights Templar

The Knights Templar drug cartel (Spanish: Caballeros Templarios) was created in Michoacán in March 2011 after the death of the charismatic leader of La Familia Michoacana cartel, Nazario Moreno González.[193] The Cartel is headed by Enrique Plancarte Solís and Servando Gómez Martínez who formed the Knights Templar due to differences with José de Jesús Méndez Vargas, who had assumed leadership of La Familia Michoacana.[194]

After the emergence of the Knights Templar, sizable battles flared up during the spring and summer months between the Knights Templar and La Familia.[8] The organization has grown from a splinter group to a dominant force over La Familia, and at the end of 2011, following the arrest of José de Jesús "El Chango" Méndez Vargas, leader of La Familia, the cartel appeared to have taken over the bulk of La Familia's operations in Mexico and the U.S.[8] In 2011 the Knights Templar appeared to have aligned with the Sinaloa Federation in an effort to root out the remnants of La Familia and to prevent Los Zetas from gaining a more substantial foothold in the Michoacán region of central Mexico.[195][196]

Alliances or agreements between drug cartels have been shown to be fragile, tense and temporary. Mexican drug cartels have increased their co-operation with U.S. street and prison gangs to expand their distribution networks within the U.S.[39] On March 31, 2014, Enrique Plancarte Solís, a high-ranking leader in the cartel, was killed by the Mexican Navy.

On 6 September 2016, A Mexican police helicopter was shot down by a gang, killing four people. The police were conducting an operation against criminal groups and drug cartels in Apatzingán, including the Knights Templar Cartel, a suspect.[197]

CJNG

The Jalisco New Generation Cartel (Spanish: Cártel de Jalisco Nueva Generación, CJNG, Los Mata Zetas and Los Torcidos)[198][199][200][201] is a Mexican criminal group based in Jalisco and headed by Nemesio Oseguera Cervantes ("El Mencho"), one of Mexico's most-wanted drug lords.[202] Jalisco New Generation Cartel started as one of splits of Milenio Cartel the other being La Resistencia. La Resistencia accused CJNG of giving up Oscar Valencia (El Lobo) to the authorities and called them Los Torcidos (The Twisted Ones). Jalisco Cartel defeated La Resistencia and took control of Millenio Cartel's smuggling networks. Jalisco New Generation Cartel expanded its operation network from coast to coast in only six months, making it one of the criminal groups with the greatest operating capacity in Mexico as of 2012.[203] Through online videos, the Jalisco New Generation Cartel has tried to seek society's approval and tacit consent from the Mexican government to confront Los Zetas by posing as a "righteous" and "nationalistic" group.[204][205] Such claims have stoked fears that Mexico, just like Colombia a generation before, may be witnessing the rise of paramilitary drug gangs.[204] By 2018 the CJNG was hyped as the most powerful cartel in Mexico,[206][207][208] though Insight Crime has said the Sinaloa Cartel is still the most powerful cartel and called the CJNG its closest rival.[209][158] In 2019, the group was greatly weakened by infighting, arrests of senior operatives, and a war with the Sinaloa Cartel and its allies,[210]

Nueva Plaza Cartel

CJNG co-founder Érick Valencia Salazar (alias "El 85") and former high-ranking CJNG leader Enrique Sánchez Martínez (alias "El Cholo") had also departed from the CJNG and formed a rival cartel known as the Nueva Plaza Cartel.[211][212][213] Since 2017, the cartel has been engaged in a war with the CJNG.[214] The Nueva Plaza Cartel has also become aligned with the Sinaloa Cartel to fight the CJNG.[211][212]

Cartel propaganda

Cartels have been engaged in religious propaganda and psychological operations to influence their rivals and those within their area of influence. They use banners or "narcomantas" to threaten their rivals. Some cartels hand out pamphlets and leaflets to conduct public relation campaigns. Many cartels have been able to control the information environment by threatening journalists, bloggers, and others who speak out against them. They have elaborate recruitment strategies targeting young adults to join their cartel groups. They have successfully branded the word "narco", and the word has become part of Mexican culture. There is music, television shows, literature, beverages, food, and architecture that all have been branded "narco".[215]

Paramilitaries

Paramilitary groups work alongside cartels to provide protection. This protection began with a focus on maintaining the drug trade; however, paramilitary groups now indulge in theft from other valuable industries such as oil and mining. It has been suggested that the rise in paramilitary groups coincides with a loss of security within the government. These paramilitary groups came about in a number of ways. First, waves of elite armed forces and government security experts have left the government to join the side of the cartels, responding to large bribes and an opportunity for wealth they may not have received in government positions. One such paramilitary group, the Zetas, employed military personnel to create one of the largest groups in Mexico. Some of the elite armed forces members who join paramilitaries are trained in the School of the Americas. One of the theories is that the paramilitaries have sprung out of deregulation of the Mexican army, which has been slowly replaced by private security firms.[216] Paramilitaries, including the Zetas, have now entered uncharted territories. Branching out of just protecting drug cartels, paramilitary groups have entered many other financially profitable industries, such as oil, gas, kidnapping, and counterfeiting electronics. There has been a complete and total loss of control by the government and the only response has been to increase army presence, notably an army whose officials are often on the drug cartels payroll. The United States has stepped in to offer support in the "War on Drugs" through funding, training and military support, and transforming the Mexican judicial system to parallel the American system.[217]

Women

Women in the Mexican Drug War have been participants and civilians. They have served for and or been harmed by all belligerents. There have been female combatants in the military, police, cartels, and gangs.[218][219] Women officials, judges, prosecutors, lawyers, paralegals,[220] reporters, business owners, social media influencers, teachers, and non-governmental organizations directors and workers have also been involved in different capacities.[221] Women citizens and foreigners, including migrants,[222] have been raped,[223][224] tortured,[225][226] and murdered in the conflict.[227][228][229][230][231]

Cartels and gangs fighting in the conflict carry out sex trafficking in Mexico as an alternative source of profits.[232][233][234][235] Some members of the criminal organizations also abduct women and girls to use as their personal sex slaves[236] and carry out sexual assault of migrants from Latin America to the United States.

Firearms

Smuggling of firearms

Mexicans have a constitutional right to own firearms,[237] but legal purchase from the single Mexican gun shop in Mexico City is extremely difficult.[238] Firearms that make their way to Mexico come from the American civilian market.[239][240] Most grenades and rocket-launchers are smuggled through Guatemalan borders, as leftovers from past conflicts in Nicaragua.[241] However some grenades are also smuggled from the U.S. to Mexico[242] or stolen from the Mexican military.[243]

The most common weapons used by the cartels are the AR-15, M16, M4, AK-47, AKM and Type 56 assault rifles. Handguns are very diverse, but the FN Five-seven (dubbed Matapolicías or Cop-killer by criminals)[244] is a popular choice due to its armor-piercing capability.[245] Grenade launchers are known to have been used against Mexican security forces, H&K G36s and M4 carbines with M203 grenade launchers have been confiscated.

Gun origins

Some researchers have asserted that most weapons and arms trafficked into Mexico come from gun dealers in the United States. There is also strong evidence for this conclusion, indicating that many of the traceable weapons come from the failed American government Operation "Fast and Furious", and there is a geographic coincidence between the supposed American origin of the firearms and the places where these weapons are seized, mainly in the northern Mexican states.[246] Most grenades and rocket-launchers are smuggled through Guatemalan borders from Central America.[241] However some grenades are also smuggled from the US to Mexico[242] or stolen from the Mexican military.[243] DHS officials have stated that the statistic is misleading: out of approximately 30,000 weapons seized in drug cases in Mexico in 2004–2008, 7,200 appeared to be of U.S. origin, approximately 4,000 were found in ATF manufacturer and importer records, and 87 percent of those—3,480—originated in the United States.[247][248]

In an effort to control smuggling of firearms, the U.S. government is assisting Mexico with technology, equipment and training.[249] Project Gunrunner was one such efforts between the U.S. and Mexico to collaborate in tracing Mexican guns which were manufactured in or imported legally to the U.S.[250]

In 2008, it was falsely reported that ninety percent of arms either captured in Mexico or interdicted were from the United States. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security and others have dispelled these claims, pointing that the Mexican sample submitted for ATF tracing is the fraction of weapons seized that appear to have been made in the U.S. or imported into the U.S.[247][248]

In 2015, official reports of the U.S. government and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) revealed that over the last years, Mexican cartels improved their firearm power, and that 71% of their weapons come from the U.S. Many of those guns were manufactured in Romania and Bulgaria, and then imported into the U.S. The Mexican cartels acquire those firearms mainly in the southern states of Texas, Arizona and California. After the United States, the top five countries of origin of firearms seized from Mexico were Spain, China, Italy, Germany and Romania. These five countries represent 17% of firearms smuggled into Mexico.[251]

Project Gunrunner

ATF Project Gunrunner has stated that the official objective is to stop the sale and export of guns from the United States into Mexico in order to deny Mexican drug cartels the firearms considered "tools of the trade".[252] However, in February 2011, it brought about a scandal when the project was accused of accomplishing the opposite by ATF permitting and facilitating "straw purchase" firearm sales to traffickers, and allowing the guns to "walk" and be transported to Mexico. Allegedly, the ATF allowed to complete the transactions to expose the supply chain and gather intelligence.[253][254] It has been established that this operation violated long-established ATF policies and practices and that it is not a recognized investigative technique.[255] Several of the guns sold under the Project Gunrunner were recovered from crime scenes in Arizona,[256] and at crime scenes throughout Mexico,[257] resulting in considerable controversy.[258][259][260]

One notable incident was the "Black Swan operation" where Joaquín Guzmán Loera was finally captured. The ATF confirmed that one of the weapons the Mexican Navy seized from Guzmán's gunmen was one of the many weapons that were "lost" during the Project Gunrunner.[261]

Many weapons from Project Gunrunner were found in a secret compartment from the "safe house" of José Antonio Marrufo "El Jaguar", one of Guzmán's most sanguinary lieutenants. He is accused of many killings in Ciudad Juárez, including the notorious massacre of 18 patients of the reahabilitation center "El Aliviane". It is believed that Marrufo armed his gunmen with weapons purchased in the United States.[262]

Operations

Operation Michoacán

Although violence between drug cartels had been occurring long before the war began, the government held a generally passive stance regarding cartel violence in the 1990s and early 2000s. That changed on December 11, 2006, when newly elected President Felipe Calderón sent 6,500 federal troops to the state of Michoacán to end drug violence there (Operation Michoacán). This action is regarded as the first major operation against organized crime, and became the starting point of the war between the government and the drug cartels.[263] Calderón escalated his anti-drug campaign, in which there are now about 45,000 troops involved in addition to state and federal police forces. In 2010 Calderón said that the cartels seek "to replace the government" and "are trying to impose a monopoly by force of arms, and are even trying to impose their own laws."[264]

As of 2011, Mexico's military captured 11,544 people who were believed to have been involved with the cartels and organized crime.[265] In the year prior, 28,000 individuals were arrested on drug-related charges. The decrease in eradication and drug seizures, as shown in statistics calculated by federal authorities, poorly reflects Calderón's security agenda. Since the war began, over forty thousand people have been killed as a result of cartel violence. During Calderón's presidential term, the murder rate of Mexico has increased dramatically.[266]

Although Calderón set out to end the violent warfare between rival cartel leaders, critics argue that he inadvertently made the problem worse. The methods that Calderón adopted involved confronting the cartels directly. These aggressive methods have resulted in public killings and torture from both the cartels and the country's own government forces, which aids in perpetuating the fear and apprehension that the citizens of Mexico have regarding the war on drugs and its negative stigma. As cartel leaders are being removed from their positions, either in the form of arrest or death, power struggles for leadership in the cartels have become more intense, resulting in enhanced violence within the cartels themselves.[267]

Calderón's forces concentrate on taking down cartel members that have a high ranking in the cartel in an attempt to take down the whole organization. The resulting struggle to fill the recently vacated position is one that threatens the existence of many lives in the cartel. Typically, many junior-level cartel members then fight amongst one another, creating more and more chaos. The drug cartels are more aggressive and forceful now than they were in the past and at this point, the cartels hold much of the power in Mexico. Calderón relies heavily on the military to defend and fight against cartel activity. Calderón's military forces have yet to yield significant results in dealing with the violent cartels due in part to the fact that many of the law enforcement officials working for the Mexican government are suspected of being corrupt. There is suspicion that cartels have corrupted and infiltrated the military at a high level, influencing many generals and officers. Mexico's National Human Rights Commission has received nearly 5,800 complaints regarding military abuse since the beginning of the drug war in 2006. Additionally, the National Human Rights Commission has completed nearly 90 in-depth reports since 2007, addressing the many human rights violations towards civilians that have occurred while the military officers were actively participating in law enforcement activities.[268]

Violence in May 2012 in which nearly 50 bodies were found on a local highway between the Mexico–United States border and Monterrey has led to the arrests of 4 high-ranking Mexican military officials.[269] These officials were suspected of being on the cartel payrolls and alerting the cartels in advance of military action against them. Such actions demonstrate that Calderón's significant military offensive will continue to reveal mixed results until the military itself is rid of the corrupting influences of the cartels whom they supposedly aim to persecute.

Escalation (2008–12)

In April 2008, General Sergio Aponte, the man in charge of the anti-drug campaign in the state of Baja California, made a number of allegations of corruption against the police forces in the region. Among his allegations, Aponte stated that he believed Baja California's anti-kidnapping squad was actually a kidnapping team working in conjunction with organized crime, and that bribed police units were being used as bodyguards for drug traffickers.[270]

These accusations sent shock waves through state government. Many of the more than 50 accused officials quit or fled. The progress against drug cartels in Mexico has been hindered by bribery, intimidation, and corruption; four months later the General was relieved of his command.[271]

On April 26, 2008, a major battle took place between members of the Tijuana and Sinaloa cartels in the city of Tijuana, Baja California, that left 17 people dead.[272]

In March 2009, President Calderón called in an additional 5,000 Mexican Army troops to Ciudad Juárez. The United States Department of Homeland Security has also said that it is considering using state National Guard troops to help the U.S. Border Patrol counter the threat of drug violence in Mexico from spilling over the border into the U.S. The governors of Arizona and Texas have encouraged the federal government to use additional National Guard troops from their states to help those already there supporting state law enforcement efforts against drug trafficking.[273]

According to the National Drug Intelligence Center, Mexican cartels are the predominant smugglers and wholesale distributors of South American cocaine and Mexico-produced cannabis, methamphetamine and heroin. Mexico's cartels have existed for some time, but have become increasingly powerful in recent years with the demise of the Medellín and Cali cartels in Colombia. The Mexican cartels are expanding their control over the distribution of these drugs in areas controlled by Colombian and Dominican criminal groups, and it is now believed they control most of the illegal drugs coming into the U.S.[274]

No longer constrained to being mere intermediaries for Colombian producers, Mexican cartels are now powerful organized-crime syndicates that dominate the drug trade in the Americas.

Mexican cartels control large swaths of Mexican territory and dozens of municipalities, and they exercise increasing influence in Mexican electoral politics.[275] The cartels are waging violent turf battles over control of key smuggling corridors from Matamoros to San Diego. Mexican cartels employ hitmen and groups of enforcers, known as sicarios. The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration reports that the Mexican drug cartels operating today along the border are far more sophisticated and dangerous than any other organized criminal group in U.S. law enforcement history.[274] The cartels use grenade launchers, automatic weapons, body armor, Kevlar helmets, and sometimes unmanned aerial vehicles.[276][277][278][279] Some groups have also been known to use improvised explosive devices (IEDs).[280]

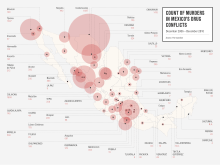

Casualty numbers have escalated significantly over time. According to a Stratfor report, the number of drug-related deaths in 2006 and 2007 (2,119 and 2,275) more than doubled to 5,207 in 2008. The number further increased substantially over the next two years, from 6,598 in 2009 to over 11,000 in 2010. According to data of the Mexican government, the death numbers are even higher: 9,616 in 2009, 15,273 in 2010, coming to a total of 47,515 killings since their military operations against drug cartels began in 2006, as stated in the government's report of January 2012.[280][281][282]

On 7 October 2012, the Mexican Navy responded to a civilian complaint reporting the presence of armed gunmen in Sabinas, Coahuila. Upon the navy's arrival, the gunmen threw grenades at the patrol from a moving vehicle, triggering a shootout that left Lazcano and another gunman dead and one marine slightly wounded.[283] The vehicle was found to contain a grenade launcher, 12 grenades, possibly a rocket-propelled grenade launcher and two rifles, according to the navy.[284] The Navy managed to confirm his death through fingerprint verification and photographs of his corpse before handing the body to the local authorities.[285] Lazcano is the most powerful cartel leader to be killed since the start of Mexico's Drug War in 2006, according to Reuters.[286]

This death came just hours after the navy arrested a high-ranking Zeta member in Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas, Salvador Alfonso Martínez Escobedo.

The apparent death of Lazcano may benefit three parties: the Mexican Navy, who scored a significant blow to organized crime with the death of Lazcano; Miguel Treviño Morales, who rose as the "uncontested" leader of Los Zetas; and Joaquín "El Chapo" Guzmán, the leader of the Sinaloa Cartel and the main rival of Los Zetas. El Chapo is perhaps the biggest winner of the three, since his primary goal is to take over the smuggling routes in Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas, the headquarters of Treviño Morales.[287] If the body had not been stolen, it would also be a symbolic victory for Felipe Calderón, who can say that his administration took down one of the founders and top leaders of Los Zetas and consequently boost the morale of the Mexican military.[288]

Analysts say that Lazcano's death does not signify the end of Los Zetas. As seen in other instances when top cartel leaders are taken out, fragmenting within the organizations occur, causing short-term violence. Los Zetas have a line of succession when leaders are arrested or killed, but the problem is that most of these replacements are younger, less-experienced members who are likely to resort to violence to maintain their reputation.[289]

Torres Félix, one of the leaders of the Sinaloa Cartel was killed in a gunbattle with the Mexican Army in the community of Oso Viejo in Culiacán, Sinaloa early in the morning on 13 October 2012. His body was sent to the forensic center and was guarded by military-men in order to prevent his henchmen from snatching the body.[290][291]

After the shootout, the military confiscated several stashes of weapons, ammunition, and other materials.[292]

Prior to his death, Torres Félix was a key figure and major drug trafficker for Ismael Zambada García and Joaquín Guzmán Loera, Mexico's most-wanted man.[293]

Effects in Mexico

Casualties

| Year | Killed |

|---|---|

| 2007 | 2,774 |

| 2008 | 5,679 |

| 2009 | 8,281 |

| 2010 | 12,658 |

| 2011 | 12,284 |

| 2012 | 12,412 |

| 2013 | 10,094 |

| 2014 | 7,993 |

| 2015 | 8,423 |

| 2016 | 10,967 |

| 2017 | 12,500 |

| 2018 | 22,500 |

| 2019 | 34,582 |

It is often not clear what deaths are part of the Mexican Drug War versus general criminal homicides, and different sources give different estimates.[294] Casualties are often measured indirectly by estimated total deaths from organized crime in Mexico.[294] This amounts to about 115,000 people in the years 2007—2018.[23]

Violence

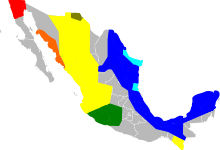

The Mexican attorney general's office has claimed that 9 of 10 victims of the Mexican Drug War are members of organized-crime groups,[295] although this figure has been questioned by other sources.[296] Deaths among military and police personnel are an estimated 7% of the total.[297] The states that suffer from the conflict most are Baja California, Guerrero, Chihuahua, Michoacán, Tamaulipas, Nuevo León and Sinaloa.

By January 2007, these various operations had extended to the states of Guerrero as well as the so-called "Golden Triangle States" of Chihuahua, Durango, and Sinaloa. In the following February the states of Nuevo León and Tamaulipas were included as well.

Seizures and arrests have jumped since Calderón took office in December 2006, and Mexico has extradited more than 100 people wanted in the U.S.

On July 10, 2008, the Mexican government announced plans to nearly double the size of its Federal Police force to reduce the role of the military in combating drug trafficking.[298] The plan, known as the Comprehensive Strategy Against Drug Trafficking, also involves purging local police forces of corrupt officers. Elements of the plan have already been set in motion, including a massive police recruiting and training effort intended to reduce the country's dependence in the drug war on the military.

On July 16, 2008, the Mexican Navy intercepted a 10-meter long narco-submarine travelling about 200 kilometers off the southwest of Oaxaca; in a raid, Special Forces rappelled from a helicopter onto the deck of the submarine and arrested four smugglers before they could scuttle their vessel. The vessel was found to be loaded with 5.8 tons of cocaine and was towed to Huatulco, Oaxaca, by a Mexican Navy patrol boat.[299][300][301][302][303]

One escalation in this conflict is the traffickers' use of new means to claim their territory and spread fear. Cartel members have broadcast executions on YouTube[304] and on other video sharing sites or shock sites, since the footage is sometimes so graphic that YouTube will not host the video. The cartels have also hung banners on streets stating their demands and/or warnings.[305]

The 2008 Morelia grenade attacks took place on September 15, 2008, when two hand grenades were thrown onto a crowded plaza, killing ten people and injuring more than 100.[306] Some see these efforts as intended to sap the morale of government agents assigned to crack down on the cartels; others see them as an effort to let citizens know who is winning the war. At least one dozen Mexican norteño musicians have been murdered. Most of the victims performed what are known as narcocorridos, popular folk songs that tell the stories of the Mexican drug trade—and celebrate its leaders as folk heroes.[307]

The extreme violence is jeopardizing foreign investment in Mexico, and the Finance Minister, Agustín Carstens, said that the deteriorating security alone is reducing gross domestic product annually by 1% in Mexico, Latin America's second-largest economy.[308]

Teachers in the Acapulco region were "extorted, kidnapped and intimidated" by cartels, including death threats demanding money. They went on strike in 2011.[309]

Government corruption

Mexican cartels advance their operations, in part, by corrupting or intimidating law enforcement officials.[270][110] Mexican municipal, state, and federal government officials, along with the police forces, often work together with the cartels in an organized network of corruption.[33] A Pax Mafioso, is a specific example of corruption which guarantees a politician votes and a following in exchange for turning a 'blind eye' towards a particular cartel.[33]

The International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) reports that although the central government of Mexico has made concerted efforts to reduce corruption in recent years, it remains a serious problem.[310][311] Some agents of the Federal Investigations Agency (AFI) are believed to work as enforcers for various cartels, and the Attorney General (PGR) reported in December 2005 that nearly 1,500 of AFI's 7,000 agents were under investigation for suspected criminal activity and 457 were facing charges.[110]

In recent years, the federal government conducted purges and prosecution of police forces in Nuevo Laredo, Michoacán, Baja California and Mexico City.[110] The anti-cartel operations begun by President Calderón in December 2006 includes ballistic checks of police weapons in places where there is concern that police are also working for the cartels. In June 2007, President Calderón purged 284 federal police commanders from all 31 states and the Federal District.[110]

Under the 'Cleanup Operation' performed in 2008, several agents and high-ranking officials have been arrested and charged with selling information or protection to drug cartels;[312][313] some high-profile arrests were: Victor Gerardo Garay Cadena,[314] (chief of the Federal Police), Noé Ramírez Mandujano (ex-chief of the Organized Crime Division (SEIDO)), José Luis Santiago Vasconcelos (ex-chief of the Organized Crime Division (SEIDO)), and Ricardo Gutiérrez Vargas who is the ex-director of Mexico's Interpol office. In January 2009, Rodolfo de la Guardia García, ex-director of Mexico's Interpol office, was arrested.[315] Julio César Godoy Toscano, who was just elected July 6, 2009 to the lower house of Congress, is charged with being a top-ranking member of La Familia Michoacana drug cartel and of protecting this cartel.[316] He is now a fugitive.

In May 2010 an NPR report collected allegations from dozens of sources, including U.S. and Mexican media, Mexican police officials, politicians, academics, and others, that Sinaloa Cartel had infiltrated and corrupted the Mexican federal government and the Mexican military by bribery and other means. According to a report by the U.S. Army Intelligence section in Leavenworth, over a 6-year period, of the 250,000 soldiers in the Mexican Army, 150,000 deserted and went into the drug industry.[317]

The 2010 NPR report also stated that Sinaloa was colluding with the government to destroy other cartels and protect itself and its leader, 'Chapo'. Mexican officials denied any corruption in the government's treatment of drug cartels.[153][154] Cartels had previously been reported as difficult to prosecute "because members of the cartels have infiltrated and corrupted the law enforcement organizations that are supposed to prosecute them, such as the Office of the Attorney General."[318]

Impact on human rights

The drug control policies Mexico has adopted to prevent drug trafficking and to eliminate the power of the drug cartels have adversely affected the human rights situation in the country. These policies have given the responsibilities for civilian drug control to the military, which has the power to not only carry out anti-drug and public security operations but also enact policy. According to the United States Department of State, the police and the military in Mexico were accused of committing serious human rights violations as they carried out government efforts to combat drug cartels.[319]

Some groups are especially vulnerable to human rights abuses collateral to drug law enforcement. Specifically in northern border states that have seen elevated levels of drug-related violence, human rights violations of injection drug users (IDUs) and sex workers by law enforcement personnel include physical and sexual violence, extortion, and targeting for accessing or possession of injection equipment or practicing sex work, although these activities are legal.[320][321][322] Such targeting is especially deleterious because members of these marginalized communities often lack the resources and social or political capital to vindicate their rights.[320][321][322]

Immense power in the executive branch and corruption in the legislative and judiciary branches also contribute to the worsening of Mexico's human rights situation, leading to such problems as police forces violating basic human rights through torture and threats, the autonomy of the military and its consequences and the ineffectiveness of the judiciary in upholding and preserving basic human rights. Some of the forms of human rights violations in recent years presented by human rights organizations include illegal arrests, secret and prolonged detention, torture, rape, extrajudicial execution, and fabrication of evidence.[323][324][325]

Drug policy fails to target high-level traffickers. In the 1970s, as part of the international Operation Condor, the Mexican government deployed 10,000 soldiers and police to a poverty-stricken region in northern Mexico plagued by drug production and leftist insurgency. Hundreds of peasants were arrested, tortured, and jailed, but no major drug traffickers were captured.[326]

The emergence of internal federal agencies that are often unregulated and unaccountable also contributes to the occurrence of human rights violations. The Federal Investigations Agency (Agencia Federal de Investigación-AFI) of Mexico had been involved with numerous human rights violation cases involving torture and corruption. In one case, detainee Guillermo Velez Mendoza died while in the custody of AFI agents. The AFI agent implicated in his death was arrested but he escaped after being released on bail.[327]

Similarly, nearly all AFI agents evaded punishment and arrest due to the corrupt executive and judiciary system and the supremacy of these agencies. The Attorney General's Office reported in December 2005 that one-fifth of its officers were under investigation for criminal activity, and that nearly 1,500 of AFI's 7,000 agents were under investigation for suspected criminal activity and 457 were facing charges.[110][328] The AFI was finally declared a failure and was disbanded in 2009.[329]

Ethnic prejudices have also emerged in the drug war, and poor and helpless indigenous communities have been targeted by the police, military, drug traffickers and the justice system. According to the National Human Rights Commission (Mexico) (Comisión Nacional de los Derechos Humanos-CNDH), nearly one-third of the indigenous prisoners in Mexico in 2001 were in prison for federal crimes, which are mostly drug-related.[330]

Another major concern is the lack of implementation of the Leahy Law in U.S. and the consequences of that in worsening the human rights situation in Mexico. Under this U.S. law, no member or unit of a foreign security force that is credibly alleged to have committed a human rights violation may receive U.S. security training. It is alleged that the U.S., by training the military and police force in Mexico, is in violation of the Leahy Law. In this case, the U.S. embassy officials in Mexico in charge of human rights and drug control programs are blamed with aiding and abetting these violations. In December 1997, a group of heavily armed Mexican special forces soldiers kidnapped twenty young men in Ocotlan, Jalisco, brutally torturing them and killing one. Six of the implicated officers had received U.S. training as part of the Grupo Aeromóvil de Fuerzas Especiales (GAFE) training program.[331]

Impact on public health

"The social fabric is so destroyed that it cannot be healed in one generation or two because wounds become deeply embedded...Mexico has a humanitarian tragedy and we have not grasped how big it is."—Elena Azaola, Centre for Social Anthropology High Studies and Research[332]

As a result of "spillover" along the U.S.-bound drug trafficking routes and more stringent border enforcement, Mexico's northern border states have seen increased levels of drug consumption and abuse, including elevated rates of drug injection 10 to 15 times the national average.[320][333][334] These rates are accompanied by mounting rates of HIV and STIs among injection drug users (IDUs) and sex workers, reaching a 5.5% prevalence in cities such as Tijuana and Ciudad Juárez, which also report STI rates of 64% and 83%, respectively.[320] Violence and extortion of IDUs and sex workers directly and indirectly elevate the levels of risk behavior and poor health outcomes among members of these groups.[320][335] Marginalization of these vulnerable groups by way of physical and sexual violence and extortion by police threatens the cross-over of infection from high-prevalence groups to the general population.[320][336][337] In particular, decreased access to public health services, such as syringe exchange programs, and confiscation of syringes, even in view of syringe access and possession being legal, can precipitate a cascade of health harms.[338][339][340] Geographic diffusion of epidemics from the northern border states elsewhere is also possible with the rotation of police and military personnel stationed in drug conflict areas with high infection prevalence.[320][336][337]

Journalists and the media

The increase in violence related with organized crime has significantly deteriorated the conditions in which local journalism is practiced.[341] In the first years of the 21st century, Mexico was considered the most dangerous country in the world to practice journalism, according to groups like the National Human Rights Commission, Reporters Without Borders, and the Committee to Protect Journalists. Between 2000 and 2012, several dozen journalists, including Miguel Ángel López Velasco, Luis Carlos Santiago, and Valentín Valdés Espinosa, were murdered there for covering narco-related news.[342][343]

The offices of Televisa and local newspapers have been bombed.[344] The cartels have also threatened to kill news reporters in the U.S. who have done coverage on the drug violence.[345] Some media networks simply stopped reporting on drug crimes, while others have been infiltrated and corrupted by drug cartels.[346][347] In 2011, Notiver journalist Miguel Angel Lopez Velasco, his wife, and his son were murdered in their home.[348]

About 74 percent of the journalists killed since 1992 in Mexico have been reporters for print newspapers, followed in number by Internet media and radio at about 11 percent each. Television journalism only includes 4 percent of the deaths.[349] These numbers are not proportional to the audience size of the different mediums; most Mexican households have a television, a large majority have a radio, but only a small number have the internet, and the circulation numbers for Mexican newspapers are relatively low.[350][351]

Since harassment neutralized many of the traditional media outlets, anonymous blogs like Blog del Narco took on the role of reporting on events related to the drug war.[352] The drug cartels responded by murdering bloggers and social media users. Twitter users have been tortured and killed for posting and denouncing information of the drug cartels' activities.[353] In September 2011, user NenaDLaredo of the website Nuevo Laredo Envivo was allegedly murdered by the Zetas.[354]

In May 2012 several journalist murders occurred in Veracruz. Regina Martinez of Proceso was murdered in Xalapa. A few days later, three Veracruz photojournalists were tortured and killed and their dismembered bodies were dumped in a canal. They had worked for various news outlets, including Notiver, Diario AZ, and TV Azteca. Human rights groups condemned the murders and demanded the authorities investigate the crimes.[343][355][356]

Murders of politicians

Since the start of the Mexican Drug War in 2006, the drug trafficking organizations have slaughtered their rivals, killed policemen, and now increasingly targeted politicians – especially local leaders.[357] Most of the places where these politicians have been killed are areas plagued by drug-related violence.[357] Part of the strategy used by the criminal groups behind the killings of local figures is the weakening of the local governments.[357] For example, María Santos Gorrostieta Salazar, the former mayor of a town in western Mexico, who had survived three earlier assassination attempts and the murder of her husband, was abducted and beaten to death in November 2012.[358] Extreme violence puts politicians at the mercy of the mafias, thus allowing the cartels to take control of the fundamental government structures and expand their criminal agendas.[357]

In addition, because mayors usually appoint local police chiefs, they are seen by the cartels as key assets in their criminal activities to control the police forces in their areas of influence.[359] The cartels also seek to control the local governments to win government contracts and concessions; these "public works" help them ingrain themselves in the community and gain the loyalty and respect of the communities in which they operate.[359] Politicians are usually targeted for three reasons: (1) Political figures who are honest pose a direct threat to organized crime, and are consequently killed by the cartels; (2) Politicians make arrangements to protect a certain cartel and are killed by a rival cartel; and (3) a cartel simply kills politicians to heat up the turf of the rival cartel that operates in the area.[360]

Massacres and exploitation of migrants

The cartels engage in kidnapping, ransom, murder, robbery, and extortion of migrants traveling from Central America through Mexico on their way to El Norte (the United States and Canada). Sometimes the cartels force the migrants to join their organization and work for them. Mass graves have been also discovered in Mexico containing bodies of migrants.[361] In 2011, 177 bodies were discovered in a mass grave in Tamaulipas, the same area where the bodies of 72 migrants were discovered in 2010.[362] In a case in San Fernando, Mexico, most of the dead had "died of blunt force trauma to the head."[363]

The cartels have also infiltrated the Mexican government's immigration agencies, and attacked and threatened immigration officers.[364] The National Human Rights Commission of Mexico (Comisión Nacional de los Derechos Humanos, CNDH) said that 11,000 migrants had been kidnapped in 6 months in 2010 by drug cartels.[365]

Human trafficking

There are documented links between the drug cartels and human trafficking for forced labor, forced prostitution, and rape. A wife of a narco described a system in which young girls became prostitutes and then were forced to work in drug factories.[366] Circa 2011, Los Zetas reportedly began to move into the prostitution business (including the prostitution of children) after previously being only 'suppliers' of women to already existing networks.[367]

The U.S. State Department says that the practice of forced labor in Mexico is larger in extent than forced prostitution.[368] Mexican journalists like Lydia Cacho have been threatened, beaten, raped, and forced into exile for reporting on these facts.[366]

Effects internationally

Europe

Improved cooperation of Mexico with the U.S. led to the recent arrests of 755 Sinaloa cartel suspects in U.S. cities and towns, but the U.S. market is being eclipsed by booming demand for cocaine in Europe, where users now pay twice the going U.S. rate.[34] U.S. Attorney General announced September 17, 2008 that an international drug interdiction operation, Project Reckoning, involving law enforcement in the United States, Italy, Canada, Mexico and Guatemala had netted more than 500 organized crime members involved in the cocaine trade. The announcement highlighted the Italian-Mexican cocaine connection.[44]

In December 2011, the government of Spain remarked that Mexican cartels have multiplied their operations in that country, becoming the main entry point of cocaine into Europe.[369]

In 2012, it was reported that Mexican drug cartels had joined forces with the Sicilian Mafia, when Italian officials unearthed information that Palermo’s black market, along with other Italian ports, was being used by Mexico's drug cartels as a conduit to bring drugs to the European market, in which they had been trafficking drugs, particularly cocaine, throughout the Atlantic Ocean for over 10 years to Europe.[370]

Guatemala