Counter-insurgency

A counter-insurgency or counterinsurgency[1] (COIN) is defined by the United States Department of State as "comprehensive civilian and military efforts taken to simultaneously defeat and contain insurgency and address its root causes".[2]

| Part of a series on |

| War |

|---|

|

|

|

Related

|

An insurgency is a rebellion against a constituted authority when those taking part in the rebellion are not recognized as belligerents.[3] It is "the organized use of subversion and violence to seize, nullify or challenge political control of a region. As such, it is primarily a political struggle, in which both sides use armed force to create space for their political, economic, and influence activities to be effective."

Counter-insurgency campaigns of duly-elected or politically recognized governments take place during war, occupation by a foreign military or police force, and when internal conflicts that involve subversion and armed rebellion occur. The most effective counterinsurgency campaigns "integrate and synchronize political, security, economic, and informational components that reinforce governmental legitimacy and effectiveness while reducing insurgent influence over the population. COIN strategies should be designed to simultaneously protect the population from insurgent violence; strengthen the legitimacy and capacity of government institutions to govern responsibly and marginalize insurgents politically, socially, and economically."[2]

Objectives

According to scholars, it is crucial to know what this strategy was designed to understand it comprehensively. COIN strategy aims to achieve the support of the local population for the government created by the host nation. The main point of the modern counterinsurgency campaign is not simply killing and capture insurgents, but to improve living conditions, support government in providing services for people and eliminate any support for insurgency.[4]

Models

–Aphorism based on the writing of Mao Zedong [5]

Counter-insurgency is normally conducted as a combination of conventional military operations and other means, such as demoralization in the form of propaganda, psy-ops, and assassinations. Counter-insurgency operations include many different facets: military, paramilitary, political, economic, psychological, and civic actions taken to defeat insurgency.

To understand counter-insurgency, one must understand insurgency to comprehend the dynamics of revolutionary warfare. Insurgents capitalize on societal problems, often called gaps; counter-insurgency addresses closing the gaps. When the gaps are wide, they create a sea of discontent, creating the environment in which the insurgent can operate.[6]

In The Insurgent Archipelago, John Mackinlay puts forward the concept of an evolution of the insurgency from the Maoist paradigm of the golden age of insurgency to the global insurgency of the start of the 21st century. He defines this distinction as 'Maoist' and 'post-Maoist' insurgency.[7]

Counter-insurgency theorists

Santa Cruz de Marcenado

The third Marques of Santa Cruz de Marcenado (1684–1732) is probably the earliest author who dealt systematically in his writings with counter-insurgency. In his Reflexiones Militares, published between 1726 and 1730, he discussed how to spot early signs of an incipient insurgency, prevent insurgencies, and counter them, if they could not be warded off. Strikingly, Santa Cruz recognized that insurgencies are usually due to real grievances: "A state rarely rises up without the fault of its governors." Consequently, he advocated clemency towards the population and good governance, to seek the people's "heart and love".[8]

B. H. Liddell Hart

The majority of counter-insurgency efforts by major powers in the last century have been spectacularly unsuccessful. This may be attributed to a number of causes. First, as B. H. Liddell Hart pointed out in the Insurgency addendum to the second version of his book Strategy: The Indirect Approach, a popular insurgency has an inherent advantage over any occupying force. He showed as a prime example the French occupation of Spain during the Napoleonic wars. Whenever Spanish forces managed to constitute themselves into a regular fighting force, the superior French forces beat them every time.

However, once dispersed and decentralized, the irregular nature of the rebel campaigns proved a decisive counter to French superiority on the battlefield. Napoleon's army had no means of effectively combatting the rebels, and in the end, their strength and morale were so sapped that when Wellington was finally able to challenge French forces in the field, the French had almost no choice but to abandon the situation.

Counter-insurgency efforts may be successful, especially when the insurgents are unpopular. The Philippine–American War, the Shining Path in Peru, and the Malayan Emergency in Malaya have been the sites of failed insurgencies.

Hart also points to the experiences of T. E. Lawrence and the Arab Revolt during World War I as another example of the power of the rebel/insurgent. Though the Ottomans often had advantages in manpower of more than 100 to 1, the Arabs' ability to materialize out of the desert, strike, and disappear again often left the Turks reeling and paralyzed, creating an opportunity for regular British forces to sweep in and finish the Turkish forces off.

In both the preceding cases, the insurgents and rebel fighters were working in conjunction with or in a manner complementary to regular forces. Such was also the case with the French Resistance during World War II and the National Liberation Front during the Vietnam War. The strategy in these cases is for the irregular combatant to weaken and destabilize the enemy to such a degree that victory is easy or assured for the regular forces. However, in many modern rebellions, one does not see rebel fighters working in conjunction with regular forces. Rather, they are home-grown militias or imported fighters who have no unified goals or objectives save to expel the occupier.

According to Liddell Hart, there are few effective counter-measures to this strategy. So long as the insurgency maintains popular support, it will retain all of its strategic advantages of mobility, invisibility, and legitimacy in its own eyes and the eyes of the people. So long as this is the situation, an insurgency essentially cannot be defeated by regular forces.

David Galula

David Galula gained his practical experience in counter-insurgency as a French officer in the Algerian War. His theory of counterinsurgency is not primarily military, but a combination of military, political and social actions under the strong control of a single authority.

Galula proposes four "laws" for counterinsurgency:[9]

- The aim of the war is to gain the support of the population rather than control of territory.

- Most of the population will be neutral in the conflict; support of the masses can be obtained with the help of an active friendly minority.

- Support of the population may be lost. The population must be efficiently protected to allow it to cooperate without fear of retribution by the opposite party.

- Order enforcement should be done progressively by removing or driving away armed opponents, then gaining the support of the population, and eventually strengthening positions by building infrastructure and setting long-term relationships with the population. This must be done area by area, using a pacified territory as a basis of operation to conquer a neighboring area.

Galula contends that:

A victory [in a counterinsurgency] is not the destruction in a given area of the insurgent's forces and his political organization. ... A victory is that plus the permanent isolation of the insurgent from the population, isolation not enforced upon the population, but maintained by and with the population. ... In conventional warfare, strength is assessed according to military or other tangible criteria, such as the number of divisions, the position they hold, the industrial resources, etc. In revolutionary warfare, strength must be assessed by the extent of support from the population as measured in terms of political organization at the grassroots. The counterinsurgent reaches a position of strength when his power is embedded in a political organization issuing from, and firmly supported by, the population.[10]

With his four principles in mind, Galula goes on to describe a general military and political strategy to put them into operation in an area that is under full insurgent control:

In a Selected Area

1. Concentrate enough armed forces to destroy or to expel the main body of armed insurgents.

2. Detach for the area sufficient troops to oppose an insurgent's comeback in strength, install these troops in the hamlets, villages, and towns where the population lives.

3. Establish contact with the population, control its movements in order to cut off its links with the guerrillas.

4. Destroy the local insurgent political organization.

5. Set up, by means of elections, new provisional local authorities.

6. Test those authorities by assigning them various concrete tasks. Replace the softs and the incompetents, give full support to the active leaders. Organize self-defense units.

7. Group and educate the leaders in a national political movement.8. Win over or suppress the last insurgent remnants.[10]

According to Galula, some of these steps can be skipped in areas that are only partially under insurgent control, and most of them are unnecessary in areas already controlled by the government.[10] Thus the essence of counterinsurgency warfare is summed up by Galula as "Build (or rebuild) a political machine from the population upward."[11]

Robert Thompson

Robert Grainger Ker Thompson wrote Defeating Communist Insurgency[12] in 1966, arguing that a successful counter-insurgency effort must be proactive in seizing the initiative from insurgents. Thompson outlines five basic principles for a successful counter-insurgency:

- The government must have a clear political aim: to establish and maintain a free, independent and united country which is politically and economically stable and viable;

- The government must function in accordance with the law;

- The government must have an overall plan;

- The government must give priority to defeating political subversion, not the guerrilla fighters;

- In the guerrilla phase of an insurgency, a government must secure its base areas first.[13]

David Kilcullen

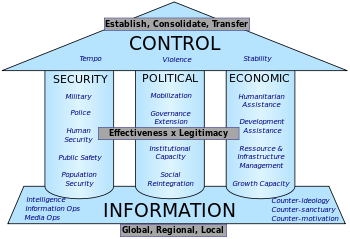

In "The Three Pillars of Counterinsurgency", Dr. David Kilcullen, the Chief Strategist of the Office of the Coordinator for Counterterrorism of the U.S. State Department in 2006, described a framework for interagency cooperation in counterinsurgency operations. His pillars – Security, Political and Economic – support the overarching goal of Control, but are based on Information:

This is because perception is crucial in developing control and influence over population groups. Substantive security, political and economic measures are critical but to be effective they must rest upon, and integrate with a broader information strategy. Every action in counterinsurgency sends a message; the purpose of the information campaign is to consolidate and unify this message. ... Importantly, the information campaign has to be conducted at a global, regional and local level — because modern insurgents draw upon global networks of sympathy, support, funding and recruitment.[14]

Kilcullen considers the three pillars to be of equal importance, because

unless they are developed in parallel, the campaign becomes unbalanced: too much economic assistance with inadequate security, for example, simply creates an array of soft targets for the insurgents. Similarly, too much security assistance without political consensus or governance simply creates more capable armed groups. In developing each pillar, we measure progress by gauging effectiveness (capability and capacity) and legitimacy (the degree to which the population accepts that government actions are in its interest).[14]

The overall goal, according to this model, "is not to reduce violence to zero or to kill every insurgent, but rather to return the overall system to normality — noting that 'normality' in one society may look different from normality in another. In each case, we seek not only to establish control, but also to consolidate that control and then transfer it to permanent, effective, and legitimate institutions."[14]

Martin van Creveld

Military historian Martin van Creveld, noting that almost all attempts to deal with insurgency have ended in failure, advises:

The first, and absolutely indispensable, thing to do is throw overboard 99 percent of the literature on counterinsurgency, counterguerrilla, counterterrorism, and the like. Since most of it was written by the losing side, it is of little value.[15]

In examining why so many counterinsurgencies by powerful militaries fail against weaker enemies, Van Creveld identifies a key dynamic that he illustrates by the metaphor of killing a child. Regardless of whether the child started the fight or how well armed the child is, an adult in a fight with a child will feel that he is acting unjustly if he harms the child and foolish if the child harms him; he will, therefore, wonder if the fight is necessary.

Van Creveld argues that "by definition, a strong counterinsurgent who uses his strength to kill the members of a small, weak organization of insurgents – let alone the civilian population by which it is surrounded, and which may lend it support – will commit crimes in an unjust cause," while "a child who is in a serious fight with an adult is justified in using every and any means available – not because he or she is right, but because he or she has no choice."[16] Every act of insurgency becomes, from the perspective of the counterinsurgent, a reason to end the conflict, while also being a reason for the insurgents to continue until victory. Trường Chinh, second in command to Ho Chi Minh of Vietnam, wrote in his Primer for Revolt:

The guiding principle of the strategy for our whole resistance must be to prolong the war. To protract the war is the key to victory. Why must the war be protracted? ... If we throw the whole of our forces into a few battles to try to decide the outcome, we shall certainly be defeated and the enemy will win. On the other hand, if while fighting we maintain our forces, expand them, train our army and people, learn military tactics ... and at the same time wear down the enemy forces, we shall weary and discourage them in such a way that, strong as they are, they will become weak and will meet defeat instead of victory.[17]

Van Creveld thus identifies "time" as the key factor in counterinsurgency. In an attempt to find lessons from the few cases of successful counterinsurgency, of which he lists two clear cases: the British efforts during The Troubles of Northern Ireland and the 1982 Hama massacre carried out by the Syrian government to suppress the Muslim Brotherhood, he asserts that the "core of the difficulty is neither military nor political, but moral" and outlines two distinct methods.[18]

The first method relies on superb intelligence, provided by those who know the natural and artificial environment of the conflict as well as the insurgents. Once such superior intelligence is gained, the counterinsurgents must be trained to a point of high professionalism and discipline such that they will exercise discrimination and restraint. Through such discrimination and restraint, the counterinsurgents do not alienate members of the populace besides those already fighting them, while delaying the time when the counterinsurgents become disgusted by their own actions and demoralized.

General Patrick Walters, British commander of troops in Northern Ireland, explicitly stated that his objective was not to kill as many terrorists as possible, but to ensure that as few people on both sides were killed. In the vast majority of counterinsurgencies, the "forces of order" kill far more people than they lose. In contrast and using very rough figures, the struggle in Northern Ireland had cost the United Kingdom three thousand casualties in dead alone. Of the three thousand, about seventeen hundred were civilians...of the remaining, a thousand were British soldiers. No more than three hundred were terrorists, a ratio of three to one.[19]

If the prerequisites for the first method – excellent intelligence, superbly trained and disciplined soldiers and police, and an iron will to avoid being provoked into lashing out – are lacking, van Creveld posits that counterinsurgents who still want to win must use the second method exemplified by the Hama massacre. In 1982, the regime of Syrian president Hafez al-Assad was on the point of being overwhelmed by the countrywide insurgency of the Muslim Brotherhood. al-Assad sent a division under his brother Rifaat to the city of Hama, known to be the center of the resistance.

Following a counterattack by the Brotherhood, Rifaat used his heavy artillery to demolish the city, killing between ten and 25 thousand people, including many women and children. Asked by reporters what had happened, Hafez al-Assad exaggerated the damage and deaths, promoted the commanders who carried out the attacks, and razed Hama's well-known great mosque, replacing it with a parking lot. With the Muslim Brotherhood scattered, the population was so cowed that it would be years before opposition groups dared to disobey the regime again and, van Creveld argues, the massacre most likely saved the regime and prevented a bloody civil war.

Van Creveld condenses al-Assad's strategy into five rules while noting that they could easily have been written by Niccolò Machiavelli:[19]

- There are situations in which cruelty is necessary, and refusing to apply necessary cruelty is a betrayal of the people who put you into power. When pressed to cruelty, never threaten your opponent but disguise your intention and feign weakness until you strike.

- Once you decide to strike, it is better to kill too many than not enough. If another strike is needed, it reduces the impact of the first strike. Repeated strikes will also endanger the morale of the counterinsurgent troops; soldiers forced to commit repeated atrocities will likely begin to resort to alcohol or drugs to force themselves to carry out orders and will inevitably lose their military edge, eventually turning into a danger to their commanders.

- Act as soon as possible. More lives will be saved by decisive action early, than by prolonging the insurgency. The longer you wait, the more inured the population will be to bloodshed, and the more barbaric your action will have to be to make an impression.

- Strike openly. Do not apologize, make excuses about "collateral damage", express regret, or promise investigations. Afterwards, make sure that as many people as possible know of your strike; media is useful for this purpose, but be careful not to let them interview survivors and arouse sympathy.

- Do not command the strike yourself, in case it doesn't work for some reason and you need to disown your commander and try another strategy. If it does work, present your commander to the world, explain what you have done and make certain that everyone understands that you are ready to strike again.[20]

Lorenzo Zambernardi

In "Counterinsurgency’s Impossible Trilemma", Dr. Lorenzo Zambernardi, an Italian academic now working in the United States, clarifies the tradeoffs involved in counterinsurgency operations.[21] He argues that counterinsurgency involves three main goals, but in real practice a counterinsurgent needs to choose two goals out of three. Relying on economic theory, this is what Zambernardi labels the "impossible trilemma" of counterinsurgency. Specifically, the impossible trilemma suggests that it is impossible to simultaneously achieve: 1) force protection, 2) distinction between enemy combatants and noncombatants, and 3) the physical elimination of insurgents.

According to Zambernardi, in pursuing any two of these three goals, a state must forgo some portion of the third objective. In particular, a state can protect its armed forces while destroying insurgents, but only by indiscriminately killing civilians as the Ottomans, Italians, and Nazis did in the Balkans, Libya, and Eastern Europe. It can choose to protect civilians along with its own armed forces instead, avoiding so-called collateral damage, but only by abandoning the objective of destroying the insurgents. Finally, a state can discriminate between combatants and noncombatants while killing insurgents, but only by increasing the risks for its own troops, because often insurgents will hide behind civilians, or appear to be civilians. So a country must choose two out of three goals and develop a strategy that can successfully accomplish them, while sacrificing the third objective.

Zambernardi's theory posits that to protect populations, which is necessary to defeat insurgencies, and to physically destroy an insurgency, the counterinsurgent's military forces must be sacrificed, risking the loss of domestic political support.

Akali Omeni

Another writer who explores a trio of features relevant to understanding counter-insurgency is Akali Omeni. Within the contemporary context, COIN warfare by African militaries tends to be at the margins of the theoretical debate - even though Africa today is faced with a number of deadly insurgencies. In Counter-insurgency in Nigeria, Omeni, a Nigerian academic, discusses the interactions between certain features away from the battlefield, which account for battlefield performance against insurgent warfare. Specifically, Omeni argues that the trio of historical experience, organisational culture (OC) and doctrine, help explain the institution of COIN within militaries and their tendency to reject the innovation and adaptation often necessary to defeat insurgency. These three features, furthermore, influence and can undermine the operational tactics and concepts adopted against insurgents. The COIN challenge, therefore, is not just operational; it also is cultural and institutional before ever it reflects on the battlefield.

According to Omeni, institutional isomorphism is a sociological phenomenon that constrains the habits of a military (in this case, the Nigerian military) to the long-established, yet increasingly ineffective, ideology of the offensive in irregular warfare. As Omeni writes,

Whereas the Nigerian military’s performance against militias in the Niger Delta already suggested the military had a poor grasp of the threat of insurgent warfare; it was further along the line, as the military struggled against Boko Haram’s threat, that the extent of this weakness was exposed. At best, the utility of force, for the Nigerian military, had become but a temporary solution against the threat of insurgent warfare. At worst, the existing model has been perpetuated at such high cost, that urgent revisionist thinking around the idea of counter-insurgency within the military institution may now be required. Additionally, the military’s decisive civil war victory, the pivot in Nigeria’s strategic culture towards a regional role, and the institutional delegitimization brought about by decades of coups and political meddling, meant that much time went by without substantive revisionism to military’s thinking around its internal function. Change moreover, where it occurred, was institutionally isomorphic and not as far removed from the military’s own origins as the intervening decades may have suggested.[22]

Further, the infantry-centric nature of the Nigerian Army's battalions, traceable all the way back to the Civil War in Nigeria back in the 1960s, is reflected in the kinetic nature of the Army's contemporary COIN approach.[23] This approach has failed to defeat Boko Haram in the way many expected. Certainly, therefore, the popular argument today, which holds that the Nigerian Army has struggled in COIN due to capabilities shortcomings, holds some merit. However, a full-spectrum analysis of the Nigeria case suggests that this popular dominant narrative scarcely scratches the surface of the true COIN challenge. This population-centered challenge, moreover, is one that militaries across the world continue to contend with. And in attempting to solve the COIN puzzle, state forces over the decades have tried a range of tactics.[24]

Information-centric theory

Starting in the early 2000s, micro-level data has transformed the analysis of effective counterinsurgency (COIN) operations. Leading this work is the "information-centric" group of theorists and researchers, led by the work of the Empirical Studies of Conflict (ESOC) group at Princeton University,[25] and the Conflict and Peace, Research and Development (CPRD) group at the University of Michigan.[26] Berman, Shapiro, and Felter have outlined the modern information-centric model.[27] In this framework, the critical determinant of counterinsurgent success is information about insurgents provided to counterinsurgents, such as insurgent locations, plans, and targets. Information can be acquired from civilian sources (human intelligence, HUMINT), or through signals intelligence (SIGINT).

Tactics

Population control

With regard to tactics, the terms "drain the water" or "drain the swamp" involves the forced relocation of the population ("water") to expose the rebels or insurgents ("fish"). In other words, relocation deprives the aforementioned of the support, cover, and resources of the local population.

One of the earliest examples of the strategy was applied by the British Empire during the Second Boer War; to segregate potential Boer supporters from Boer Commandos, scorched earth tactics were used to destroy Boer farmland while Boers were shipped abroad or confined to concentration camps converted from refugee camps for displaced Boers. The tactic was later refined in the Briggs Plan during the Malayan Emergency, when predominantly Chinese rural population centers with suspected Malayan Races Liberation Army sympathizers were gutted and their populations transferred to enclosed and guarded "New Villages" to control and monitor population activity; to improve local support for the British, New Villages were equipped with adequate basic amenities, including running water, electricity, and health and education services.

A somewhat similar strategy was used extensively by US forces in South Vietnam until 1969, initially by forcing the rural population into fenced, secured villages, referred to as Strategic Hamlets, and later by declaring the areas people in the Strategic Hamlets had come from as free-fire zones to remove the remainder of the population from their villages and farms. Widespread use was made of Agent Orange (which was first used on a large scale by the British during the Malayan Emergency), sprayed from airplanes, to destroy crops that might have provided resources for Viet Cong and North Vietnamese troops and their human support base. These measures proved ineffective, since Phạm Ngọc Thảo, who oversaw the program, was a communist agent and sabotaged the implementation of the hamlets. This allowed Viet Cong activists and sympathizers to infiltrate the new communities.[28] In any event, the Vietnam War was only partly a counter-insurgency campaign, as it also involved conventional combat between US/ARVN forces, Vietcong Main Force Battalions, and the North Vietnamese Army (NVA).

According to a report of the Naval Postgraduate School:

Among the most effective means are such population-control measures as vehicle and personnel checkpoints and national identity cards. In Malaya, the requirement to carry an ID card with a photo and thumbprint forced the communists to abandon their original three-phase political-military strategy and caused divisive infighting among their leaders over how to respond to this effective population-control measure.[29]

Oil spot

The oil spot approach is the concentration of counter-insurgent forces into an expanding, secured zone. The origins of the expression is to be found in its initial use by Marshal Hubert Lyautey, the main theoretician of French colonial warfare and counter-insurgency strategy.[30][31] The oil spot approach was later one of the justifications given in the Pentagon Papers[32] for the Strategic Hamlet Program.

Cordon and search

Cordon and search is a military tactic, one of the basic counter-insurgency operations[33] in which an area is cordoned off and premises are searched for weapons or insurgents.[34][35] Other related operations are "Cordon and knock"[36][37] and "Cordon and kick". "Cordon and search" is part of new doctrine called Stability and Support Operations or SASO. It is a technique used where there is no hard intelligence of weapons in the house and therefore is less intense than a normal house search. It is used in urban neighborhoods. The purpose of the mission is to search a house with as little inconvenience to the resident family as possible.

Air operations

Air power can play an important role in counter-insurgency, capable of carrying out a wide range of operations:

- Transportation in support of combatants and civilians alike, including casualty evacuations;

- Intelligence gathering, surveillance, and reconnaissance;

- Psychological operations, through leaflet drops, loudspeakers, and radio broadcasts;

- Air-to-ground attack against 'soft' targets.[38]

Public diplomacy

In General David Petraeus’ Counterinsurgency Field Manual, one of the many tactics described to help win in counterinsurgency warfare involves the use of public diplomacy through military means.[39] Counterinsurgency is effective when it is integrated "into a comprehensive strategy employing all instruments of national power," including public diplomacy. The goal of COIN operations is to render the insurgents as ineffective and non-influential, by having strong and secure relations with the population of the host nation.

An understanding of the host nation and the environment that the COIN operations will take place in is essential. Public diplomacy in COIN warfare is only effective when there is a clear understanding of the culture and population at hand. One of the largest factors needed for defeating an insurgency involves understanding the populace, how they interact with the insurgents, how they interact with non-government organizations in the area, and how they view the counterinsurgency operations themselves.

Ethics is a common public diplomacy aspect that is emphasized in COIN warfare. Insurgents win their war by attacking internal will and the international opposition. In order to combat these tactics the counterinsurgency operations need to treat their prisoners and detainees humanely and according to American values and principles. By doing this, COIN operations show the host nation's population that they can be trusted and that they are concerned about the well being of the population in order to be successful in warfare.

"Political, social, and economic programs are usually more valuable than conventional military operations in addressing the root causes of the conflict and undermining the insurgency."[40] These programs are essential in order to gain the support of the population. These programs are designed to make the local population feel secure, safe, and more aligned with the counterinsurgency efforts; this enables the citizens of the host nation to trust the goals and purposes of the counterinsurgency efforts, as opposed to the insurgents’. A counterinsurgency is a battle of ideas and the implementation and integration of these programs is important for success. Social, political and economic programs should be coordinated and administered by the host nation's leaders, as well. Successful COIN warfare allows the population to see that the counterinsurgency efforts are including the host nation in their re-building programs. The war is fought among the people and for the people between the insurgents and the counterinsurgents.

A counterinsurgency is won by utilizing strategic communications and information operations successfully. A counterinsurgency is a competition of ideas, ideologies, and socio-political movements. In order to combat insurgent ideologies one must understand the values and characteristics of the ideology or religion. Additionally, counterinsurgency efforts need to understand the culture of which the insurgency resides, in order to strategically launch information and communication operations against the insurgent ideology or religion. Counterinsurgency information operatives need to also identify key audiences, communicators, and public leaders to know whom to influence and reach out to with their information.[41]

Information operations

Public diplomacy in information operations can only be achieved by a complete understanding of the culture it is operating in. Counterinsurgency operations must be able to perceive the world from the locals’ perspective. To develop a comprehensive cultural picture counterinsurgency efforts should invest in employing "media consultants, finance and business experts, psychologists, organizational network analysts, and scholars from a wide range of disciplines."[41] Most importantly, counterinsurgency efforts need to be able to understand why the local population is drawn into the insurgent ideology, like what aspects are appealing and how insurgents use information to draw their followers into the ideology. Counterinsurgency communication efforts need a baseline understanding of values, attitudes, and perceptions of the people in the area of operations to conduct successful public diplomacy to defeat the enemy.

Developing information and communication strategies involve providing a legitimate alternate ideology, improving security and economic opportunity, and strengthening family ties outside of the insurgency. In order to conduct public diplomacy through these means, counterinsurgency communication needs to match its deeds with its words. Information provided through public diplomacy during a counterinsurgency cannot lie, the information and communication to the people always has to be truthful and trustworthy in order to be effective at countering the insurgents. Public diplomacy in counterinsurgency to influence the public thoughts and ideas is a long time engagement and should not be done through negative campaigning about the enemy.

Conducting public diplomacy through relaying information and communicating with the public in a counterinsurgency is most successful when a conversation can happen between the counterinsurgency team and the local population of the area of operation. Building rapport with the public involves "listening, paying attention, and being responsive and proactive" which is sufficient for the local population to understand and trust the counterinsurgency efforts and vice versa.[41] This relationship is stringent upon the counterinsurgents keeping their promises, providing security to the locals, and communicating their message directly and quickly in times of need.

Understanding and influencing the cognitive dimension of the local population is essential to winning counterinsurgency warfare. The people's perception of legitimacy about the host nation and the foreign country's counterinsurgency efforts is where success is determined. "The free flow of information present in all theaters via television, telephone, and Internet, can present conflicting messages and quickly defeat the intended effects."[42] Coordination between the counterinsurgency operations, the host nation, and the local media in information presented to the public is essential to showing and influencing how the local population perceives the counterinsurgency efforts and the host nation.

Public opinion, the media, and rumors influence how the people view counterinsurgency, the government hosting their efforts, and the host nation legitimacy. The use of public diplomacy to strategically relay the correct messages and information to the public is essential to success in a counterinsurgency operation. For example, close relationships with media members in the area is essential to ensure that the locals understand the counterinsurgency objectives and feel secure with the host nation government and the counterinsurgency efforts. If the local media is not in sync with the counterinsurgency operatives then they could spread incomplete or false information about the counterinsurgency campaign to the public.

"Given Al Qaeda’s global reach, the United States must develop a more integrated strategic communication strategy for counter-insurgency with its allies to diminish violent rhetoric, improve its image abroad, and detect, deter, and defeat this social movement at its many levels."[41] Information operations and communicative abilities are one of the largest and most influence aspects of public diplomacy within a counterinsurgency.

Public diplomacy is especially important as modern insurgents are more easily able to gain support through a variety of sources, both local and transnational, thanks to advances in increased communication and globalization. Consequently, modern counter-insurgency requires attention to be focused on an insurgency's ecosystem from the national to the local level, in order to deprive the insurgency of support and prevent future insurgent groups from forming.[43]

Specific doctrines

Vietnam War

During the Vietnam War, counter-insurgency initially formed part of the earlier war as Diem had implemented the poorly conceived Strategic Hamlet Program, a similar model to the Malayan Emergency, which had opposite effects. Similarly economic and rural development formed a key strategy as part of Rural Affairs development.[44] While the earlier war was marked by considerable emphasis on counter-insurgency programs US forces initially relied on very little if any theoretical doctrine of counter-insurgency during the Ground-Intervention phase. Conventional warfare using massive fire-power and failure to implement adequate counter-insurgency had extremely negative effects and was the strategy whom the NVA were adept at countering through the protracted political and military warfare model. These are in part, reasons for the outright failure of U.S strategic policy in the war.[44] Following the replacement of General William Westmoreland, newer concepts were tried including a revival of earlier COIN strategies including Civil Operations and Revolutionary Development Support. This was alongside the brutal and oftentimes badly implemented civilian-assassination program Phoenix Program targeting Viet Cong civilian personnel. These reasons were contributing factors to the U.S failure as it had become too late by then.

British Empire

Malaya

British forces were able to employ the relocation method with considerable success during the "Malayan Emergency". The Briggs Plan, implemented fully in 1950, relocated Chinese Malayans into protected "New Villages", designated by British forces. By the end of 1951, some 400,000 ethnic Chinese had moved into the fortifications. Of this population, the British forces were able to form a "Home Guard", armed for resistance against the Malayan Communist Party, an implementation mirrored by the Strategic Hamlet Program later used by US forces in South Vietnam.[45][46] Despite British claims of a victory in the Malayan Emergency, military historian Martin van Creveld noted that the end result of the counterinsurgency, namely the withdrawal of British forces and establishment of an independent state, are identical to that of Aden, Kenya and Cyprus, which are not considered victories.[47]

Dutch Empire

The Dutch formulated a new strategy of counter-insurgency warfare, during the Aceh War by deploying light-armed Marechaussee units and using scorched earth tactics.

In 1898 Van Heutsz was proclaimed governor of Aceh, and with his lieutenant, later Dutch Prime Minister Hendrikus Colijn, would finally conquer most of Aceh. They followed Hurgronje's suggestions, finding cooperative uleebelang or secular chiefs that would support them in the countryside and isolating the resistance from their rural support base.

During the South Sulawesi Campaign Captain Raymond Westerling of the KST, Special Forces of the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army used the Westerling Method. Westerling ordered the registration of all Javanese arriving in Makassar due to the large numbers of Javanese participating in the Sulawesi resistance. He also used scouts to infiltrate local villages and to identify members of the resistance.[48]

Based on their information and that of the Dutch military intelligence service, the DST surrounded one of more suspected villages during night, after which they drove the population to a central location. At daybreak, the operation began, often led by Westerling. Men would be separated from women and children. From the gathered information Westerling exposed certain people as terrorists and murderers. They were shot without any further investigation. Afterwards Westerling forced local communities to refrain from supporting guerillas by swearing on the Quran and established local self-defence units with some members recruited from former guerrillas deemed as "redeemable".

Westerling directed eleven operations throughout the campaign. He succeeded in eliminating the insurgency and undermining local support for the Republicans. His actions restored Dutch rule in southern Sulawesi. However, the Netherlands East Indies government and the Dutch army command soon realised that Westerling's notoriety led to growing public criticism. In April 1947 the Dutch government instituted an official inquiry of his controversial methods. Raymond Westerling was put on the sidelines. He was relieved of his duties in November 1948.

France

France had major counterinsurgency wars in its colonies in Indochina and Algeria. McClintock cited the basic points of French doctrine as:[49]

- Quadrillage (an administrative grid of population and territory)

- Ratissage (cordoning and "raking")

- Regroupement (relocating and closely controlling a suspect population)

- ‘Tache d'huile' – The 'oil spot' strategy

- Recruitment of local leaders and forces

- Paramilitary organization and militias

Much of the thinking was informed by the work of earlier leading French theoreticians of colonial warfare and counter-insurgency, Marshals Bugeaud, Gallieni and Lyautey.[31]

While McClintock cites the 1894 Algerian governor, Jules Cambon, as saying "By destroying the administration and local government we were also suppressing our means of action. ...The result is that we are today confronted by a sort of human dust on which we have no influence and in which movements take place which are unknown to us." Cambon's philosophy, however, did not seem to survive into the Algerian War of Independence, (1954–1962).

Indochina

Post-WWII doctrine, as in Indochina, took a more drastic view of "Guerre révolutionnaire", which presented an ideological and global war, with a commitment to total war. Countermeasures, in principle, needed to be both political and military; "No measure was too drastic to meet the new threat of revolution." French forces taking control from the Japanese did not seem to negotiate seriously with nationalist elements in what was to become Vietnam,[51] and reaped the consequences of overconfidence at Điện Biên Phủ.[52]

It occurred to various commanders that soldiers trained to operate as guerrillas would have a strong sense of how to fight guerrillas. Before the partition of French Indochina, French Groupement de commandos mixtes aéroportés (GCMA), led by Roger Trinquier,[53] took on this role, drawing on French experience with the Jedburgh teams.[54] GCMA, operating in Tonkin and Laos under French intelligence, was complemented by Commandos Nord Viêt-Nam in the North. In these missions, the SOF teams lived and fought with the locals. One Laotian, who became an officer, was Vang Pao, who was to become a general in Hmong and Laotian operations in Southeast Asia while the US forces increased their role.

Algeria

The French counterinsurgency in colonial Algeria was a savage one. The 1957 Battle of Algiers resulted in 24,000 detentions, with most tortured and an estimated 3,000 killed. It may have broken the National Liberation Front infrastructure in Algiers, but it also killed off French legitimacy as far as "hearts and minds" went.[49][55]

Counter-insurgency requires an extremely capable intelligence infrastructure endowed with human sources and deep cultural knowledge. This contributes to the difficulty that foreign, as opposed to indigenous, powers have in counter-insurgent operations. One of France's most influential theorists was Roger Trinquier. The Modern Warfare counterinsurgency strategy described by Trinquier, who had led anti-communist guerrillas in Indochina, was a strong influence on French efforts in Algeria.

Trinquier suggested three principles:

- separate the guerrilla from the population that supports him;

- occupy the zones that the guerrillas previously operated from, making the area dangerous for the insurgents and turning the people against the guerrilla movement; and

- coordinate actions over a wide area and for a long enough time that the guerrilla is denied access to the population centres that could support him.

Trinquier's view was that torture had to be extremely focused and limited, but many French officers considered its use corrosive to its own side. There were strong protests among French leaders: the Army's most decorated officer, General Jacques Pâris de Bollardière, confronted General Jacques Massu, the commander of French forces in the Battle of Algiers, over orders institutionalizing torture, as "an unleashing of deplorable instincts which no longer knew any limits." He issued an open letter condemning the danger to the army of the loss of its moral values "under the fallacious pretext of immediate expediency", and was imprisoned for sixty days.[49]

As some of the French Army protested, other parts increased the intensity of their approach, which led to an attempted military coup against the French Fourth Republic itself. Massu and General Raoul Salan led a 1958 coup in Algiers, demanding a new Republic under Charles de Gaulle. When de Gaulle's policies toward Algeria, such as a 1961 referendum on Algerian self-determination, did not meet the expectations of the colonial officers, Salan formed the underground Organisation armée secrète (OAS), a right-wing terrorist group, whose actions included a 1962 assassination attempt against de Gaulle himself.

West Africa

France has had taken Barnett's Leviathan role[56] in Chad and Ivory Coast, the latter on two occasions, most significantly in 2002–2003.[57] The situation with France and Ivory Coast is not a classic FID situation, as France attacked Ivorian forces that had provoked UN peacekeepers.

Another noteworthy instance of counter-insurgency in West Africa is the Nigerian military experience against Boko Haram militant Islamists. Military operations against the group occur predominantly in the far north-east areas of Nigeria. These operations have been ongoing since June 2011, and have greatly expanded within the Lake Chad Basin sub-region of West Africa.[58]

India

There have been many insurgencies in India since its independence in 1947. The Kashmir insurgency, which started by 1989, was brought under control by Indian government and violence has been reduced. A branch of the Indian Army known as the Rashtriya Rifles (RR) was created for the sole purpose of destroying the insurgency in Kashmir, and it has played a major role in doing so. The RR was well supported by Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF), Border Security Force (BSF), Indo-Tibetan Border Police (ITBP) and state government police.

The Counter Insurgency and Jungle Warfare School (CIJWS) is located in the northeastern town of Vairengte in the Indian state of Mizoram. Personnel from countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Russia, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Bangladesh and Vietnam have attended this school.[59] High quality graduate level training by a joint staff of highly trained special operators at Camp Taji Phoenix Academy and the Counterinsurgency Centre For Excellence is provided in India[60] as well as many Indian Officers.

Portugal

Portugal's experience in counterinsurgency resulted from the "pacification" campaigns conducted in the Portuguese African and Asian colonies in the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century.

In the 1960s and early 1970s, Portugal conducted large scale counterinsurgency operations in Angola, Portuguese Guinea and Mozambique against independentist guerrillas supported by the Eastern Bloc and China, as well by some Western countries. Although these campaigns are collectively known as the "Portuguese Colonial War", there were in fact three different ones: the Angolan Independence War, the Guinea-Bissau War of Independence and the Mozambican War of Independence. The situation was unique in that small armed forces – those of Portugal – were able to conduct three counterinsurgency wars at the same time, in three different theatres of operations separated by thousands of kilometers. For these operations, Portugal developed its own counterinsurgency doctrine.[61]

Russia and The Soviet Union

The most familiar Russian counterinsurgency is the War in Afghanistan from 1979–1989. However, throughout the history of Czarist Russian, the Russians fought many counterinsurgencies as new Caucasian and Central Asian territory were occupied.[62] It was in these conflicts that the Russians developed the following counterinsurgency tactics:[62]

- Deploy a significant number of troops

- Isolate the area from outside assistance

- Establish tight control of major cities and towns

- Build lines of forts to restrict insurgent movement

- Destroy the springs of resistance through destruction of settlements, livestock, crops etc.

These tactics, generally speaking, were carried over into Soviet use following the 1917 revolution for the most part, say for the integration of political-military command.[63] This tactical blue print saw use following the First and Second World Wars in Dagestan, the Caucasus, Central Asia, Siberia, Lithuania and Ukraine.[62] This doctrine was ultimately shown to be inadequate in The Soviet War in Afghanistan, mostly due to insufficient troop commitment, and in the Wars in Chechnya.[62]

United States

The United States has conducted counterinsurgency campaigns during the Philippine–American War, the Vietnam War, the post-2001 War in Afghanistan, and the Iraq War. The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have resulted in increased interest in counterinsurgency within the American military, exemplified by the 2006 publication of a new joint Army Field Manual 3-24/Marine Corps Warfighting Publication No. 3-33.5, Counterinsurgency, which replaced the documents separately published by the Army and Marine Corps 20–25 years prior.[64] Views of the doctrine contained in the manual has been mixed.[65] The 2014 version of FM 3-24/MCWP 3-33.5 acquired a new title, Insurgencies and Countering Insurgencies, it consists of three main parts,

Part one provides strategic and operational context, part two provides the doctrine for understanding insurgencies, and part three provides doctrine for defeating an insurgency. In short, FM 3-24/MCWP 3-33.5 is organized to provide the context of a problem, the problem, and possible solutions.[66]

William B. Caldwell IV wrote:

The law of armed conflict requires that, to use force, "combatants" must distinguish individuals presenting a threat from innocent civilians. This basic principle is accepted by all disciplined militaries. In the counterinsurgency, disciplined application of force is even more critical because our enemies camouflage themselves in the civilian population. Our success in Iraq depends on our ability to treat the civilian population with humanity and dignity, even as we remain ready to immediately defend ourselves or Iraqi civilians when a threat is detected.[67]

In the recent conflicts the 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) has been increasingly involved conducting special operations especially the training and development of other states' military and security forces.[68][69] This is known in the special operations community as foreign internal defense. It was announced 14 January 2016 that 1,800 soldiers from the 101st's Headquarters and its 2nd Brigade Combat Team will deploy soon on regular rotations to Baghdad and Irbil to train and advise Iraqi army and Kurdish Peshmerga forces who are expected in the coming months to move toward Mosul, the Islamic State group's de facto headquarters in Iraq.[70]

The 101st Airborne Division will serve an integral role in preparing Iraqi ground troops to expel the Islamic State group from Mosul, Defense Secretary Ash Carter told the division's soldiers during a January 2016 visit to Fort Campbell, Kentucky.[69] Defense Secretary Ash Carter told the 101st Airborne Division that "The Iraqi and peshmerga forces you will train, advise and assist have proven their determination, their resiliency, and increasingly, their capability, but they need you to continue building on that success, preparing them for the fight today and the long hard fight for their future. They need your skill. They need your experience."[69]

Foreign internal defense policymaking has subsequently aided in Iraqi successes in reclaiming Tikrit, Baiji, Ramadi, Fallujah, and Mosul from the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant.

Recent evaluations of U.S. counterinsurgency efforts in Afghanistan have yielded mixed results. A comprehensive study by the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction concluded that "the U.S. government greatly overestimated its ability" to use COIN and stabilization tactics for longterm success.[71] The report found that "successes in stabilizing Afghan districts rarely lasted longer than the physical presence of coalition troops and civilians." These findings are corroborated by scholarly studies of U.S. counterinsurgency activities in Afghanistan, which determined that backlashes by insurgents and the local population were common.[72][73][74]

In October 2019 at a Workshop at RAND, Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense Mick Mulroy rolled out the Irregular Warfare Annex (IWA) to the National Defense Strategy of 2018. He explained that irregular warfare included counter-insurgency, counter-terrorism, unconventional warfare, foreign internal defense, sabotage and subversion, as well as stabilization and information operations. It had traditionally been perceived as a predominately counterterrorism (CT) effort used to fight violent extremist organizations, but that under the IWA the skills will be applied to all areas of military competition. These included competition against global powers competitors like China and Russia as well as rogue states like North Korea and Iran.[75] Mulroy said that the U.S. must be prepared to respond with "aggressive, dynamic, and unorthodox approaches to IW," to be competitive across these priorities. He also explained that under the IWA, both special operations and conventional forces would play a key role.[76][75]

See also

|

|

References

Notes

- See American and British English spelling differences#Compounds and hyphens

- U.S. Government Counterinsurgency Guide (PDF). Bureau of Political-Military Affairs, Department of State. 2009. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- "insurgent B. n. One who rises in revolt against constituted authority; a rebel who is not recognized as a belligerent." Oxford English Dictionary, second edition (1989)

- "A Decade at War: Afghanistan, Iraq and Counterinsurgency | America Abroad Media". americaabroadmedia.org. Retrieved 2017-11-26.

- Mao Zedong. On Guerrilla Warfare (1937), Chapter 6 - "The Political Problems of Guerrilla Warfare": "Many people think it impossible for guerrillas to exist for long in the enemy's rear. Such a belief reveals lack of comprehension of the relationship that should exist between the people and the troops. The former may be likened to water the latter to the fish who inhabit it. How may it be said that these two cannot exist together? It is only undisciplined troops who make the people their enemies and who, like the fish out of its native element cannot live."

- Eizenstat, Stuart E.; John Edward Porter; Jeremy M. Weinstein (January–February 2005). "Rebuilding Weak States" (PDF). Foreign Affairs. 84 (1).

- John Mackinlay, The Insurgent Archipelago, (London: Hurst, 2009).

- Excerpts from Santa Cruz's writings, translated into English, in Beatrice Heuser: The Strategy Makers: Thoughts on War and Society from Machiavelli to Clausewitz (Santa Monica, CA: Greenwood/Praeger, 2010), ISBN 978-0-275-99826-4, pp. 124-146.

- Reeder, Brett. "Book Summary of Counterinsurgency Warfare: Theory and Practice by David Galula". Crinfo.org (The Conflict Resolution Information Source). Retrieved 2008-09-22.

- Galula, David Counterinsurgency Warfare: Theory and Practice Westport, Connecticut: Praeger Security International, 1964. ISBN 0-275-99303-5 p.54-56

- Galula p.95

- Thompson, Robert (1966). Defeating Communist insurgency: the lessons of Malaya and Vietnam. New York: F.A. Praeger.

- Hamilton, Donald W. (1998). The art of insurgency: American military policy and the failure of strategy in Southeast Asia. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-95734-6.

- Kilcullen, David (28 September 2006). "Three Pillars of Counterinsurgency" (PDF).

- van Creveld, p. 268

- van Creveld, p. 226

- van Creveld, pp. 229-230

- van Creveld, p. 269

- van Creveld, p. 235

- van Creveld, pp. 241–245

- Zambernardi, Lorenzo, "Counterinsurgency's Impossible Trilemma", The Washington Quarterly, 33:3, July 2010, pp. 21-34

- Omeni, Akali (2017) Counter-insurgency in Nigeria: The Military and Operations Against Boko Haram, 2011-17. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. pp. 52-53.

- Omeni, Akali (2018) Insurgency and War in Nigeria: Regional Fracture and the Fight Against Boko Haram (forthcoming) I.B. Tauris.

- Omeni, Akali (2017) Counter-insurgency in Nigeria: The Military and Operations against Boko Haram, 2011-17. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge

- "Research Highlights | Empirical Studies of Conflict".

- "Center for Political Studies - Conflict & Peace, Research & Development (CPRD)".

- Berman, Eli; Shapiro, Jacob; Felter, Joseph (2018). Small Wars, Big Data. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400890118.

- Karnow, p. 274

- Sepp, Kalev I. (May–June 2005). "Best Practices in Counterinsurgency" (PDF). Military Review: 8–12.

- Lyautey, Hubert. Du rôle colonial de l'armée (Paris: Armand Colin, 1900)

- Porch, Douglas. "Bugeaud, Galliéni, Lyautey: The Development of French colonial warfare", in Paret, Peter; Craig, Gordon Alexande; Gilbert, Felix (eds). Makers of Modern Strategy: From Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), pp. 376-407.

- "Pentagon Papers, Gravel Edition, Volume 3, Chapter 1, "US Programs in South Vietnam, Nov. 1963-Apr. 1965,: section 1". Mtholyoke.edu. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- "Basic Counter-Insurgency". Military History Online. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- "Vignette 7: Search (Cordon and Search)". Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 2013-09-04.

- "Tactics 101: 026. Cordon and Search Operations". Armchair General. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- Chronology: How the Mosul raid unfolded. Retrieved 28.07.2005.

- Used in "Operation Quick Strike" in Iraq on August 6, 2005. Retrieved 11 January 2007. Archived December 30, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Sagraves, Robert D (April 2005). "The Indirect Approach: the role of Aviation Foreign Internal Defense in Combating Terrorism in Weak and Failing States" (PDF). Air Command and Staff College. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-04-14. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Petraeus, David H.; Amos, James F. (2006). FM 3-24/MCWP 3-33.5 Counterinsurgency (PDF). pp. li–liv.

- Petraeus, General David H. (2006). Counterinsurgency Field Manual (PDF). pp. 2–1.

- Krawchuk, Fred T. (Winter 2006). "Strategic Communication: An Integral Component of Counterinsurgency Operations". The Quarterly Journal. 5. 3: 35–50. Archived from the original on October 7, 2011. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- Joint Publication 3-24 (October 2009). Counterinsurgency Operations (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-02-21. Retrieved 2011-04-03.

- Kilcullen, David (Nov 30, 2006). "Counter-insurgency Redux". Survival: Global Politics and Strategy. 48 (4): 113–130. doi:10.1080/00396330601062790.

- "Counterinsurgency in Vietnam: Lessons for Today - The Foreign Service Journal - April 2015". www.afsa.org.

- Nagl, John (2002). Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife: Counterinsurgency Lessons from Malaya and Vietnam. Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-275-97695-8.

- Thompson, Robert (1966). Defeating Communist Insurgency: Lessons from Malaya and Vietnam. Chatto & Windus. ISBN 978-0-7011-1133-5.

- van Creveld, p. 221

- http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2010/05/19/westerling039s-war.html

- McClintock, Michael (November 2005). "Great Power Counterinsurgency". Human Rights First.

- Pike, Douglas. PAVN: People's Army of Vietnam. (Presidio: 1996) pp. 37-169

- Patti, Archimedes L.A. (1980). Why Vietnam? Prelude to America's Albatross. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-04156-1.

- Fall, Bernard B (2002). Hell in a Very Small Place: The Siege of Dien Bien Phu. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81157-9.

- Trinquier, Roger (1961). Modern Warfare: A French View of Counterinsurgency. ISBN 978-0-275-99267-5. Archived from the original on 2008-01-12. Retrieved 2007-02-13.

- Porte, Rémy. "Intelligence in Indochina: Discretion and Professionalism were rewarded when put into Practice" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 25, 2006. Retrieved 2007-11-26.

- Tomes, Robert R. (2004). "Relearning Counterinsurgency Warfare" (PDF). Parameters. United States Army War College.

- Barnett, Thomas P.M. (2005). The Pentagon's New Map: The Pentagon's New Map: War and Peace in the Twenty-first Century. Berkley Trade. ISBN 978-0-425-20239-5. Barnett-2005.

- Corporal Z.B. "Ivory Coast – Heart of Darkness". Archived from the original on 2011-05-10.

- Omeni, Akali. 2017. Counter-insurgency in Nigeria: The Military and Operations against Boko Haram, 2011-17. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- "Army's jungle school a global hit". Dawn Online. 10 April 2004.

- IRNA - Islamic Republic News Agency. "US army officers will receive training in guerrilla warfare in Mizoram". Globalsecurity.org.

- Cann, Jonh P., Counterinsurgency in Africa: The Portuguese Way of War, 1961-1974, Hailer Publishing, 2005

- James, Joes, Anthony (2004). Resisting rebellion : the history and politics of counterinsurgency. Lexington, Ky.: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0813171999. OCLC 69255762.

- G., Butson, Thomas (1984). The tsar's lieutenant : the Soviet marshal. New York: Praeger. ISBN 978-0030706837. OCLC 10533399.

- "FM 3-24/MCWP 3-33.5 Counterinsurgency. (Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited.)". Everyspec.com. 2006-12-15. Retrieved 2013-09-04.

- Hodge, Nathan (14 January 2009). "New Administration's Counterinsurgency Guide?". Wired. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

Melton, Stephen L. (9 April 2013). "Aligning FM 3-24 Counterinsurgency with Reality". Small Wars Journal. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

Paul, Christopher; Clarke, Colin P. "Evidentiary Validation of FM 3-24: Counterinsurgency Worldwide, 1978-2008". NDU Press. National Defense University. Archived from the original on 6 March 2013. Retrieved 24 June 2013. - FM 3-24/MCWP 3-33.5 Insurgencies and Countering Insurgencies, Headquarters, Department of the Army, 14 May 2014. (Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited.)

- Caldwell, William B. (8 February 2007). "Not at all vague". Washington Times. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- Cox, Matthew. "Army to Deploy 101st Airborne Soldiers to Oversee Iraqi Army Training". military.com.

- "Carter to Army's 101st: You will prepare Iraqis to retake Mosul". stripes.com.

- 1,800 soldiers from the 101st's Headquarters and its 2nd Brigade Combat Team will deploy soon on regular rotations to Baghdad and Irbil to train and advise Iraqi army and Kurdish peshmerga forces who are expected in the coming months to move toward Mosul, the Islamic State group's de facto headquarters in Iraq.

- Stabilization: Lessons From The U.S. Experience in Afghanistan (PDF). Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction. 2018. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

- "Investing in the Fight: Assessing the Use of the Commander's Emergency Response Program in Afghanistan" (PDF). RAND Corporation. 2016. Retrieved January 30, 2019. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Sexton, Renard (November 2016). "Aid as a Tool against Insurgency: Evidence from Contested and Controlled Territory in Afghanistan". American Political Science Review. 110 (4): 731–749. doi:10.1017/S0003055416000356. ISSN 0003-0554.

- Eli, Berman (2018-05-13). Small wars, big data : the information revolution in modern conflict. Felter, Joseph H.,, Shapiro, Jacob N.,, McIntyre, Vestal. Princeton, New Jersey. ISBN 9780691177076. OCLC 1004927100.

- "Pentagon turns to irregular tactics to counter Iran". 2019-10-17.

- "NSRD Hosts Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for the Middle East, Michael Mulroy".

Further reading

| Library resources about Counter-insurgency |

- Arreguin-Toft, Ivan. How the Weak Win Wars: A Theory of Asymmetric Conflict. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005), ISBN 0-521-54869-1.

- Arreguin-Toft, Ivan. "Tunnel at the End of the Light: A Critique of U.S. Counter-terrorist Grand Strategy," Cambridge Review of International Affairs, Vol. 15, No. 3 (2002), pp. 549–563.

- Arreguin-Toft, Ivan. "How to Lose a War on Terror: A Comparative Analysis of a Counterinsurgency Success and Failure", in Jan Ångström and Isabelle Duyvesteyn, Eds., Understanding Victory and Defeat in Contemporary War. (London: Frank Cass, 2007).

- Burgoyne, Michael L. and Albert J. Marckwardt (2009). The Defense of Jisr al-Doreaa With E. D. Swinton's "The Defence of Duffer's Drift". University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-08093-2.

- Callwell, C. E., Small Wars: Their Principles & Practice. (Lincoln, Nebraska: Bison Books, 1996), ISBN 0-8032-6366-X.

- Cassidy, Robert M. Counterinsurgency and the Global War on Terror: Military Culture and Irregular War. (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008).

- Catignani, Sergio. Israeli Counter-Insurgency and the two Intifadas: Dilemmas of a Conventional Army. (London: Routledge, 2008), ISBN 978-0-415-43388-4.

- Corum, James. Bad Strategies: How Major Powers Fail in Counterinsurgency. (Minneapolis, MN: Zenith, 2008), ISBN 0-7603-3080-8.

- Corum, James. Fighting the War on Terror: A Counterinsurgency Strategy. (Minneapolis, MN: Zenith, 2007), ISBN 0-7603-2868-4.

- Galula, David. Counterinsurgency Warfare: Theory and Practice. (Wesport, Connecticut: Praeger, 1964), ISBN 0-275-99269-1.

- Derradji Abder-Rahmane. The Algerian Guerrilla Campaign Strategy & Tactics. (New York: Edwin Mellen Press, 1997)

- Erickson, Edward J. (2013) Ottomans and Armenians: A Study in Counterinsurgency. New York: Palgrave Macmillan ISBN 978-1349472604

- Erickson,Edward J. (2019) A Global History of Relocation in Counterinsurgency Warfare. London: Bloomsbury Academic ISBN 9781350062580

- Joes, James Anthony. Resisting Rebellion: The History and Politics of Counterinsurgency. (Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 2004), ISBN 0-8131-9170-X.

- Karnow, Stanley (1997). Vietnam: A history. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-670-84218-6.

- Kilcullen, David. The Accidental Guerrilla: Fighting Small Wars in the Midst of a Big One. (London: Hurst, 2009).

- Kilcullen, David. Counterinsurgency. (London: Hurst, 2010).

- Kitson, Frank, Low Intensity Operations: Subversion, Insurgency and Peacekeeping. (1971)

- Larson, Luke. Senator's Son: An Iraq War Novel. (Phoenix: Key Edition, 2010), ISBN 0-615-35379-7.

- Mackinlay, John. The Insurgent Archipelago. (London: Hurst, 2009).

- Mao Zedong. Aspects of China's Anti-Japanese Struggle (1948).

- Melson, Charles D. "German Counter-Insurgency Revisited." Journal of Slavic Military Studies 24#1 (2011): 115–146. online

- Merom, Gil. How Democracies Lose Small Wars: State, Society, and the Failures of France in Algeria, Israel in Lebanon, and the United States in Vietnam. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003), ISBN 0-521-00877-8

- Polack, Peter (2019) Guerrilla Warfare; Kings of Revolution. Haverstown, Pennsylvania: Casemate. ISBN 9781612006758

- Thompson, Robert (1966) Defeating Communist Insurgency: Experiences from Malaya and Vietnam.. London: Chatto & Windus.

- Tomes, Robert (Spring 2004) "Relearning Counterinsurgency Warfare", Parameters

- Van Creveld, Martin (2008) The Changing Face of War: Combat from the Marne to Iraq, New York: Ballantine. ISBN 978-0-89141-902-0

- Warndorf, Nicholas (2017) Unconventional Warfare in the Ottoman Empire: The Armenian Revolt and the Turkish Counterinsurgency. Offenbach am Main: Manzara Verlag. ISBN 978-3939795759

- Zambernardi, Lorenzo. "Counterinsurgency's Impossible Trilemma", The Washington Quarterly, Vol. 33, No. 3 (2010), pp. 21–34.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Counter-insurgency warfare. |

- "Insurgency: The Transformation of Peasant Rebellion" by Raj Desai and Harry Eckstein

- Small Wars Journal: Insurgency/Counterinsurgency Research page

- CNAS, Abu Muquwama 'The Counterinsurgency Reading List'

- The U.S. Army Stability Operations Field Manual

- Terrorism prevention in Russia: one year after Beslan

- "Military Operations in Low Intensity Conflict" U.S. Depts. of the Army and Air Force

- "Inside Counterinsurgency" by Stan Goff, ex - U.S. Special Forces

- "Instruments of Statecraft – U.S. Guerrilla Warfare, Counterinsurgency, and Counterterrorism, 1940–1990" by Michael McClintock

- "Counter-Revolutionary Violence – Bloodbaths in Fact & Propaganda" by Noam Chomsky and Edward S. Herman

- "The Warsaw Ghetto Is No More" by SS Brigade Commander Jürgen Stroop

- "Insurgency and Counterinsurgency in the 21st Century" by Steven Metz and Raymond Millen

- Wired News article on game theory in war on terror

- Military forces in counterterrorism and counterinsurgency operations at JihadMonitor.org

- "Counter Insurgency Jungle Warfare School India"

- "Bibliography: Theories of Limited War and Counterinsurgency" by Edwin Moise (Vietnam-era)

- "Bibliography: Doctrine on Insurgency and Counterinsurgency" Edwin Moise (recent)

- "Military Briefing Book" news regarding counter-insurgency

- Max Boot - Invisible Armies, YouTube video, length 56:30, Published on Mar 25, 2013

- U.S. Army/Marine corps counter insurgency field manual, pdf document

- http://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/book-excerpt-guerrilla-warfare-kings-revolution

.jpg)