Women in the military

Women have served in the military in many different roles in various jurisdictions throughout history.

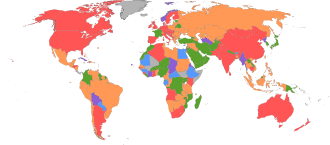

Women in military world

women not permitted in military.

women permitted in military, no further information

Women permitted in the military, but treated unequally (for example, not allowed in frontline combat)

Women permitted in the military, treated as equals

conscription for women

No data, no armed forces, no stable form of government or ongoing/recent policy changes.

|

Since 1914, in western militaries, women have served in greater numbers and more diverse roles than before. In the 1970s, most Western armies began allowing women to serve in active duty in all military branches.[1] In 2006, eight countries (China, Eritrea, Israel, Libya, Malaysia, North Korea, Peru and Taiwan) conscripted women into military service.[2] In 2013, Norway became the first NATO country to draft women, as well as the first country in the world to conscript women on the same formal terms as men. In 2017, neighboring Sweden followed suit and in 2018, the Netherlands joined this line-up (although in the Netherlands there is no active peacetime conscription).[3][4]

In 2018, only two countries conscripted women and men on the same formal conditions: Norway and Sweden.[5][6] A few other countries have laws allowing for the conscription of women into their armed forces, however with some difference such as service exemptions, length of service, and more.[7]

History

World War I

During the First World War, the United States was in total warfare efforts.[8] Every person had to help in contributing to the war. However, this doesn't necessarily mean that everyone needed to fight. The country needed to continue to fund its troops and support the war financially while soldiers were fighting. The United States relied on organizations to support war efforts. Women joined organizations such as the Committee on Public Information in order to educate people about the war. This committee additionally promoted nationality. In addition to working for committees having to do with education, women worked in all sorts of positions. Many women became YWCA members and went overseas to help soldiers. This was the first time in history that women of all classes were working together to help the war efforts.[9] Upper-class women founded many voluntary war organizations while middle and lower-class women worked in these organizations by working as nurses or by filling in the jobs of men.

Russia

The only nation to deploy female combat troops in substantial numbers was Russia. From the onset, female recruits either joined the military in disguise or were tacitly accepted by their units. The most prominent were a contingent of front-line light cavalry in a Cossack regiment commanded by a female colonel, Alexandra Kudasheva. Others included Maria Bochkareva, who was decorated three times and promoted to senior NCO rank, while The New York Times reported that a group of twelve schoolgirls from Moscow had enlisted together disguised as young men.[10] In 1917, the Provisional Government raised a number of "Women's Battalions", with Bochkareva given an officer's commission in command. They were disbanded before the end of the year. In the later Russian Civil War, they fought both for the Bolsheviks (infantry) and the White Guard.[11]

Others

In Serbia, a few individual women played key military roles. Scottish doctor Elsie Ingles coordinated a retreat of approximately 8,000 Serbian troops through Romania and revolutionary Russia, up to Scandinavia and finally onto transport ships back to England .[12][13] Another woman, Milunka Savic, enlisted in the Serbian army in place of her brother. She fought throughout the war, becoming possibly the most decorated woman in military history.[14][15]

In 1918 Loretta Walsh became the first woman to enlist as a woman. A 1948 law made women a permanent part of the military services. In 1976, the first group of women were admitted into a U.S. military academy.[16] Approximately 16% of the 2013 West Point class consisted of women.[17] In the 1918 Finnish Civil War, more than 2,000 women fought in the Women's Red Guards.[18]

During the Spanish Civil War, thousands of women fought in mixed-gender combat and rearguard units, or as part of militias.[19][20]

World War II

All the major participating nations in World War II enlisted women. The majority served as nursing and clerical or support roles. Over 500,000 women had combat roles in anti-aircraft units in Britain and Germany, as well as front-line units in the Soviet Union.

India

In 1942, the Indian National Army (Azaad Hind Fauj) established India's first all women regiment to fight for Indian independence under the leadership of Subash Chandra Bose, with Japanese assistance.[22] It is estimated that over 1,000 women served in the regiment.[23]

United Kingdom

In 1938, the British took the lead in establishing uniformed services for women (small units of nurses had long been in service). In late 1941, Britain began conscripting women, sending most into factories and some into the military, especially the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS) attached to the army. The ATS began as a women's auxiliary in 1938. In 1941, the ATS was granted military status, although women received only two thirds of male pay. Women had a well-publicized role in handling anti-aircraft guns against German planes and V-1 missiles. The daughter of Prime Minister Winston Churchill was there, and he said that any general who saved him 40,000 fighting men had gained the equivalent of a victory. By August 1941, women were operating fire-control instruments; although they were never allowed to pull the trigger, since killing the enemy was considered to be too masculine.[24] By 1943, 56,000 women were in Anti-Aircraft Command, mostly in units close to London where they faced a risk of death, but not of capture.[21][25] The first death of a woman in Anti-Aircraft Command occurred in April 1942.[26]

Germany

The Third Reich had similar roles for women. The SS-Helferinnen were regarded as part of the SS if they had undergone training at a Reichsschule SS. All other female workers were contracted to the SS and chosen largely from concentration camps. Women served in auxiliary units in the navy (Kriegshelferinnen), air force (Luftnachrichtenhelferinnen) and army (Nachrichtenhelferin).[27][28]

In 1944-45 roughly 500,000 women were volunteer uniformed auxiliaries in the German armed forces (Wehrmacht). About the same number served in civil aerial defense, 400,000 volunteered as nurses and many more replaced drafted men in the wartime economy.[28] In the Luftwaffe they served in combat roles helping to operate anti-aircraft systems to shoot down Allied bombers. By 1945, German women held 85% of the billets as clerics, accountants, interpreters, laboratory workers and administrative workers, together with half of the clerical and junior administrative posts in high-level field headquarters.[29]

The German nursing service consisted of four main organizations, one for Catholics, one for Protestants, the secular DRK (Red Cross) and the "Brown Nurses," for committed Nazi women. Military nursing was primarily handled by the DRK, which came under partial Nazi control. Frontline medical services were provided by male medics and doctors. Red Cross nurses served widely within the military medical services, staffing the hospitals close to the front lines and at risk of attack. Two dozen were awarded the Iron Cross for heroism under fire.[27] Brown Nurses were forced to look away while their incapacitated patients were murdered by war criminals.[30]

Hundreds of women auxiliaries (Aufseherin) served in the SS in the camps, the majority of which were at Ravensbrück.

In Germany, women worked and were told by Hitler to produce more pure Aryan children to fight in future wars.[31]

Japanese American Women

During the second world war, many Japanese American women lost their jobs or pay because they were sent to relocation camps. Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans were faced with discrimination. Many Americans called it the "yellow peril"[32] and called Japanese people "japs". In 1913, California passed the Alien Land Law which prohibited "aliens ineligible for citizenship" from owning land to grow crops on. Despite the discrimination, many Japanese American women volunteered to serve in the Women's Auxiliary Army Corps. Sexism along with racism was something that these women faced when they joined WAAC. Even while dealing with discrimination, Japanese American women were able to greatly help the United States. Many women were hired as interpreters, translators, and interrogators in the Military Intelligence Service. In 1948, the Women's Army Corps was permanently established and remained until 1978 when women were allowed into the army.

Italy

In Italy, during the second world war, the Female Auxiliary Service (Italian: Servizio Ausiliario Femminile, SAF) was a women's' corps of the armed forces of the Italian Social Republic, whose components, all voluntary, were commonly referred to as auxiliaries. The commander was the Brig. Gen. Piera Gatteschi Fondelli.

Yugoslav Partisans

The Yugoslav National Liberation Movement had 6,000,000 civilian supporters; its two million women formed the Antifascist Front of Women (AFŽ), in which the revolutionary coexisted with the traditional. The AFŽ managed schools, hospitals and local governments. About 100,000 women served with 600,000 men in Tito's Yugoslav National Liberation Army. It stressed its dedication to women's rights and gender equality and used the imagery of folklore heroines to attract and legitimize the fighters.[33] After the war, although women were relegated to traditional gender roles, Yugoslavia's historians emphasized women's roles in the resistance. After Yugoslavia broke up in the 1990s, women's contributions to the resistance were forgotten.[34][35]

Vietnam War

Though relatively little official data exists about female Vietnam War veterans, the Vietnam Women's Memorial Foundation estimates that approximately 11,000 military women were stationed in Vietnam during the conflict. Nearly all of them were volunteers, and 90 percent served as military nurses, though women also worked as physicians, air traffic controllers, intelligence officers, clerks and other positions in the U.S. Women's Army Corps, U.S. Navy, Air Force and Marines and the Army Medical Specialist Corps. In addition to women in the armed forces, an unknown number of civilian women served in Vietnam on behalf of the Red Cross, United Service Organizations (USO), Catholic Relief Services and other humanitarian organizations, or as foreign correspondents for various news organizations.[36]

In addition to the U.S. military women who served in Vietnam, an unknown number of female civilians willingly gave their services on Vietnamese soil during the conflict. Many of them worked on behalf of the American Red Cross, Army Special Services, United Service Organizations (USO), Peace Corps, and various religious groups such as Catholic Relief Services.[37]

Other American women traveled to Vietnam as foreign correspondents for news organizations, including Georgette "Dickey" Chappelle, a writer for the National Observer who was killed by a mine while on patrol with U.S.[38] Marines outside Chu Lai in November 1965. According to the Vietnam Women's Memorial Foundation, 59 female civilians died during the conflict.

Democratic Republic of the Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo began training an initial 150 women as para-commandos for the Armée Nationale Congolaise in 1967. Many more were trained subsequently, over a period of years. The women received parachute and weapons training, although it is unclear to what extent they were actually integrated into the combat units of the Congo.

Eritrea

In 1999, the BBC reported that about a quarter of the Eritrean soldiers in the Eritrean–Ethiopian War were women.[39]

Israel

Israel is the only country with conscription for women.[40][41][42] Mandatory conscription for single and married women without children began in 1948.[43]

Initially, women conscripts served in the Women's Army Corps, serving as clerks, drivers, welfare workers, nurses, radio operators, flight controllers, ordnance personnel and instructors.[44] Roles for women beyond technical and secretarial support began opening up in the late 1970s and early 1980s.[41]

In 2000, the Equality amendment to the Military Service law granted equal opportunities in the military to women found physically and personally suitable for a job. Women started to enter combat support and light combat roles in a few areas, including the Artillery Corps, infantry units and armored divisions. A few platoons named Carakal were formed for men and women to serve together in light infantry. Many women joined the Border Police.[41]

Despite these changes, fewer than 4 percent of women service members are in combat positions such as infantry, crew of tanks or other armored vehicles, artillery guns service, fighter pilots, etc. Rather, they are concentrated in "combat-support".[45]

Gulf War

In 1990 and 1991, some 40,000 American military women were deployed during the Gulf War operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm; however, no women served in combat. A policy enacted in 1994 prohibited women from assignment to ground combat units below the brigade level.[46]

21st century

The proportion of female military personnel varies internationally; for example, it is approximately 3% in India, 10% in the UK,[47] 15% in France,[48] 13% in Sweden,[49] 16% in the US,[50] 15.3% in Canada,[51] and 27% in South Africa.[52] While a marginal percentage of women are reported in military service globally, estimates following the increasing trend of military women capped predictions at about 10% for 1980.[53] As expressed by the current percentages, these numbers have not risen much past that, with the exception of South Africa. Many state armed forces that recruit women continue to bar them from ground close combat roles (roles that would require them to kill at close quarters).[54] This practice preserves male domination within militaries. In limiting female entry, militaries have maintained their characteristic brutal masculinity.[55] Compared with male personnel and female civilians, female personnel face substantially higher risks of sexual harassment and sexual violence, according to British,[56] Canadian[57] and US[58] research. Not only have women been left unprotected, but the major cause of PTSD experienced by women is identified as military sexual trauma (MST). The male experience of PTSD derives from that of combat trauma.[55]

Combat

Some nations allow female soldiers to serve in certain combat arms positions. Others exclude them for various reasons including physical demands and privacy policies. Among the NATO nations, and as of the mid-1970s, women were able to attain military status in the following countries: Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, the Federal Republic of Germany, Greece, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Turkey, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Non-conscription countries, notably the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada are where the highest levels of female military presences were achieved.[59] Canada is marked as particularly progressive in its early implementation of gender equality practices.[55] A rise in the call for equal opportunity coupled with the decline of able-bodied men willing to enter military service coaxed countries to reform policies toward female inclusion.[59] With the opening of submarine service in 2000, women now had free rein to enlist in any kind of military service.[55]

United States

The United States military opens all positions to women.[60] Units such as Special Forces require members to meet extraordinary requirements, and no females have met them in some units.

Women have not historically been required to register for Selective Services; however, Federal Judge Gray Miller ruled on February 2, 2019[61] that an all male draft is unconstitutional.[62] Unless Congress acts first, this challenge to the constitution could go to the United States Supreme Court.[63] The issue was brought when Marc Angelucci sued the Selective Service on behalf of the National Coalition for Men.[62] Currently the Federal Judge's challenge to the constitution has yet to be addressed.

History

Women have been involved in the U.S. military since 1775, originally in the civilian fields of nursing, laundering, mending clothing and cooking.

Deborah Sampson was one of the first women to enlist while disguised as a man. She was unhappy with her limited role in the American Revolution. She served in a light infantry unit, fighting in many battles. Injuries put her in a hospital where her secret was discovered. Her commanding officer, General John Paterson, honorably discharged her and thanked her for her service.[64]

Many women contributed to the Civil War, whether it was through nursing, spying or physically fighting on the battlefield. An example of this is seen through Belle Royd. She began her career as a spy and messenger at the young age of 17. By the time she had become 20, she became quite famous in the United States in which people called her the Cleopatra of the Confederacy. As a spy, she provided confederate leaders with valuable information. She was arrested multiple times and put into prison. Eventually, she was banished from federal soil and was told she would receive a death sentence if she were caught on federal soil again.[65] Those who fought in the war, disguised themselves as males, and went by men's aliases.[66] It wasn't extremely difficult for women to conceal their true identities because soldiers showered separately and were fully clothed the majority of the time. In addition, both men and women would join the army with no previous military experience, so their training was very similar and the women would not stand out.[66]

The most common way for women to be discovered was through injury.[66] For instance, in 1861, Mary Owens enlisted into the Union Army disguised as the "brother" of William Evans, who was actually the love of her life. They could not stand to be separated. Her job was to deliver handwritten messages to commanders on the battlefield so that she would avoid combat. After her lover was killed in battle, Mary decided to avenge his death by fighting in the battlefield. She received a massive gash on her forehead for which she was sent to the hospital for treatment. It was during this moment that her female identity was revealed and she was discharged from the military.[67] Those who were discovered would either be sent home or faced with punishment.[66] However, Mary was warmly welcomed back into her town.

Other disguised were often uncovered by chance. Sarah Collins was a strong woman who believed she could do the job of a male soldier. Her brother, who was also a soldier, assisted her in disguising as a man by cutting her hair short and dressing her up in men's apparel. Unfortunately, her disguise was not perfect as her true identity was uncovered in the way she properly placed her shoe's that was unlike a male's method of placing shoes. Sarah was then sent home while her brother remained fighting.[68] It is difficult for historians to accurately estimate the true number of women who fought in the war because of their disguise and aliases, as well as their desire of discretion. Women joined the fray of the Civil War for similar reasons as men: the promise of a steady wage, innate sense of patriotism, or for the thrill of an adventure. Some women would even follow their loved ones into battle.[69]

In 1917 Loretta Walsh became the first woman to enlist as a woman. A 1948 law made women a permanent part of the military services. In 1976, the first group of women were admitted into a U.S. military academy.[70] Approximately 16% of the 2013 West Point class consisted of women.[71]

In 1990 and 1991, some 40,000 American military women were deployed during the Gulf War operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm; however, no women served in combat. A policy enacted in 1994 prohibited women from assignment to ground combat units below the brigade level.[72]

Policy changes

Until 1993, 67 percent of the positions in the Army were open to women.

In 2013, 15.6 percent of the Army's 1.1 million soldiers, including National Guard And Reserve, were female, serving in 95 percent of occupations.[73] As of 2017 78 percent of the positions in the Army are open to women.[74] In the U.S. Air Force, 99% of career fields are open to women, with the only exceptions Special Tactics Officer, Combat Control, Special Operations Weather Technician, Combat Rescue Officer, Pararescue and Tactical Air Control Party.[75]

In January 2013, the US ended the policy of "no women in units that are tasked with direct combat".[76]

In 2013 female US Army soldiers enrolled in a training course designed by Combined Joint Task Force Paladin, specifically designed for Female Engagement Team members. The course was intended to train female soldiers for tasks such as unexploded ordnance awareness, biometrics, forensics, evidence collection, tactical questioning, vehicle and personnel searches and homemade explosive devices.[77]

By May 2015, none of the nineteen women vying to become the first female Army Rangers had passed Ranger School. Eleven of the nineteen dropped out in the first four days. Of the remaining eight who failed in the next step, three were given the option to.[78] Two graduated in August 2015.[79] A third graduated in October 2015.[80]

In April 2015 after two-and-a-half-year period in which the Marine Corps' Infantry Officer Course became gender-integrated for research, ended without a single female graduate.[81] The final two participants failed the initial Combat Endurance Test.[82]

In 2016 all combat jobs opened to women.[83]

Women have been injured, killed, and awarded high honors. Two women received the Silver Star: Sergeant Leigh Ann Hester in 2005 and Army Specialist Monica Lin Brown in 2007 for their actions in combat. Over 10,000 combat action badges were awarded to women who served in combat in Iraq and Afghanistan.[84][84]

Physical, social, and cultural issues

.jpg)

A 2015 Marine Corps study[85][86] found that women in a unit created to assess female combat performance were significantly injured twice as often as men, less accurate with infantry weapons and not as good at removing wounded troops from the battlefield.[85]

The study assessed a nine-month experiment at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, and Twentynine Palms, California. About 400 Marines, including 100 women, volunteered to participate.[87]

Male squads, teams, and crews demonstrated better performance on 93 of 134 tasks evaluated (69 percent) than units with women in them. Male units were faster while completing tactical movements in combat situations, especially in units with large "crew-served" weapons such as heavy machine guns and mortars. Male infantry squads had better accuracy than squads with women in them, with "a notable difference between genders for every individual weapons system" used by infantry rifleman units. The M4 carbine, M27 infantry automatic rifle and M203 single-shot grenade launcher were assessed.[87]

Male Marines who had not received infantry training were more accurate than women who had. In removing wounded troops from the battlefield, "notable differences in execution times were found between all-male and gender-integrated groups".[87]

Unit cohesion was lower in mixed gender units. Many female soldiers reported that the way that they are viewed by male soldiers is often detrimental to their participation. For instance, female soldiers are often labelled as "either standoffish or a slut".[88] In order to avoid such labels, female soldiers have to spend time with fellow soldiers strategically, without spending too much time with any one of them. This approach often has an isolating effect.[88] In several instances, women were considered less skilled than male soldiers, so were not given opportunities to complete tasks for which they were qualified.[88]

According to Lieutenant colonel Dave Grossman, author of On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society, Israeli soldiers reacted with uncontrollable protectiveness and aggression after seeing a woman wounded. Further, Islamic militants rarely, if ever, surrender to female soldiers, lessening the IDF's ability to take prisoners. Iraqi and Afghan civilians are often not intimidated by female soldiers. However, in socially conservative environments, female combat soldiers can search female civilians, while children and women are more likely to talk to female soldiers than to male soldiers.[89]

Sexual harassment and assault

One 2009 report concluded that military women were three times more likely to be raped than civilians;[90] and that women soldiers in Iraq were more likely to be attacked by another soldier than by an insurgent.[91] In 1988, the first military-wide sexual harassment survey found that 64% of military women had been subjected to some form of sexual harassment. The most affected were Native-Americans, followed by Hispanics and African-Americans.[92]

U.S. Senator Martha McSally, an Arizona Republican, said during a Senate meeting on sexual assault in the military that she was raped by a superior officer in the U.S. Air Force. McSally was the first female combat pilot in the U.S. Air Force. She said that she never reported it because so many people did not trust the system, blamed herself, was ashamed and confused, thought she was strong but felt powerless.[93]

Sexual assault: What it is and the process

Sexual assault is more likely to occur in the military than in the civilian population. One in four active-duty female military personnel will be sexually assaulted.[94] The military has a Code Of Justice which defines sexual assault: rape, aggravated assault, abusive sexual assault, nonconsensual sodomy (forced oral or anal sex), or attempts to commit these acts.

All of these acts are punishable by military law which begins by the victim going forward to their commander. It is then their job to make an inquiry on the perpetrator, however they also have the right to dismiss the claims. They can also the right to take non-judicial punishment or take it to high authority. If the perpetrator's punishment can go from dismissal, to dishonorable discharge to confinement in military prison. If found with the crime of rape the perpetrator can carry a lifetime of imprisonment to in extreme cases even execution.[95] When women went to report their sexual assault 83% of the victims stated that their experiences with military legal personnel made them reluctant to seek further help.[96]

Many victims in the military describe the response to and aftermath of sexual assault as more painful than the assault itself because of the unspoken "code of silence", which implies that women should keep quiet about their assault and not come forward to take action. Women expect that little will be done, so most cases go unreported. When they are reported and taken to court only ten percent of cases have the perpetrator charged for their crimes, which is a reason women won't come forward as they know little will come from it.[96]

Female soldiers have developed several techniques for avoiding sexual assault "including: (1) relying on support networks [buddy systems], (2) capitalizing on their status (associated with rank, age, time spent in military, or prior deployment experience); and, (3) masking femininity through clothing to minimize violence exposure and to keep themselves and others safe during military service".[97] Such strategies leave the burden of addressing the problem on potential victims.[97] Conversely, in many units, soldiers pair off as "buddies" who watch out for each other. In mostly male units, females buddy with males who then often becomes excessively protective, reducing the female's agency.[98]

A lawsuit seeks redress for military plaintiffs who claim to have been subjected to sexual assault.[99] The Invisible War addresses this lawsuit and topic.[100]

Effects of sexual assault

Sexual assault leads to many health problems for women in the military such as anxiety disorders, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, substance abuse, binge eating, dissociation and memory impairment, suicidal and parasuicidal behavior, sexual dysfunction and dissatisfaction, poor self-esteem, and personality disorders, such as borderline personality disorder. It also takes a toll on their physical health and have reported having menstrual complications, headaches, back pain, gastrointestinal pain.[101]

All of these factors make it hard for women to stay in the military, in women it is the leading cause for early leave of the armed forces. Once leaving the military though women have a hard time reintegrating back into society and can end up homeless. It is so debilitating for women in the military because most of their perpetrates are people they work and live with, from peers to a supervisor and higher above. This close relationship creates a new type of trauma as the victim is forced to see them every day and creates an overall lack of trust in people.[102]

They more often fail to complete college, and generally earn incomes less than $25,000.[103] Their work can involve frequent interactions with their attacker, and damages trust in the institution. Perpetrators are typically in a higher position have the job to protect the woman, increasing trauma.[104]

Updated military training focuses on bystander interventions and the role of consent in sexual activity, emphasizing the responsibility of male soldiers.[98] Some female soldiers assume the classically male role of "protector". This works to change women's "responsibility for preventing rape"[98] and requires that male soldiers acknowledge their responsibility to engage with female soldiers in all activities.

Women on submarines

In 1985 the Royal Norwegian Navy became the first[105] navy in the world to permit female personnel to serve in submarines. The first female submarine commander was Captain Solveig Krey aboard the first Kobben class submarine on 11 September 1995.[106] The Danish Navy allowed women on submarines in 1988, the Swedish Navy in 1989,[105] followed by the Royal Australian Navy in 1998, Canada in 2000 and Spain.[107]

On April 29, 2010, the United States Navy authorized women to serve aboard submarines.[108] Previously, objections such as the need for separate accommodation and facilities (estimates that modifying submarines to accommodate women would cost $300,000 per bunk versus $4,000 per bunk on aircraft carriers) had prevented the change.[109] The Navy stated that larger SSGN and SSBN submarines had more available space and could accommodate female officers with little/no modification. Qualified female candidates with the desire to serve were available. (Women then represented 15 percent of active duty sailors[110] and were earning about half of all science and engineering bachelor's degrees.)[110][111]

In May 2014, it was announced that three women had become the UK Royal Navy's first female submariners.[112]

On November 15, 2017, the first Argentinian female submarine officer Eliana Krawczyk, disappeared in the Atlantic Ocean after the Argentinean Navy lost contact with ARA San Juan submarine after a reported failure in the electric system.[113] As one of the 44 crew members lost at sea, Krawczyk was honoured by the country's Jewish community as "La Reina De Los Mares" on International Women's Day in 2018.[114]

On 4 July 2017, after two years of training, four female officers boarded a French SSBN for France's first seventy-day mixed gender patrol.[115] The next generation of French submarines is designed to welcome women.[116]

Women are expected to join submarine crews in the Royal Netherlands Navy in 2019, with the addition of shower doors and changing-room curtains.[117]

In 2020, Risa Takenouchi became the first female student to enroll in Japan's MSDF Submarine Training Center, following the overturning of restriction of women submariners.[118]

Academic studies

A 2008 study found that female cadets saw military training as an "opportunity to be strong, assertive and skillful" and saw such training "as an escape from some of the negative aspects of traditional femininity". The female cadets also believed that the ROTC program was "gender-blind" and "gender-neutral". The study claims that female cadets "were hyper-vigilant about their status as women performing tasks traditionally seen as men's work and often felt that they had to constantly prove they were capable."[119]

The study quoted one female cadet: "in the Navy the joke is that a woman in the Navy is either a bitch, a slut or a lesbian, and none of them are good categories to fall into, and if you are stern with your people then you are a bitch, but if you're a guy and stern people are like, wow, I respect him for being a good leader."[119]

84 percent of cadets said they did not want a military career as it would interfere with marriage and raising children.[119]

A 2009 study examined the attitudes of West Point cadets, Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) cadets, and non-military-affiliated students from civilian colleges toward a variety of military roles. Cadets were less approving of assigning women to certain military jobs than others.[120]

As of 2018 only two women have completed the United States Marine's Infantry Officer Course,[121] while in 2016 86% of women failed the Marines' combat jobs test.[122]

See also

- Women in combat

- Women in the military by country

- Women in war

- Women in warfare and the military (1945–1999)

- Women in warfare and the military (2000–present)

- Women in the military in the Americas

- Puerto Rican women in the military

- Women in the military in Europe

- Women in the Philippine military

- Women in the United States Air Force

- Women in the United States Army

- Women in the United States Coast Guard

- Women in the United States Marines

- Women in the United States Navy

- List of women warriors in folklore

Notes

- Carreiras, Helena (2006). Gender and the military: women in the armed forces of western democracies. New York: Routledge. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-415-38358-5.

- "Women in the military — international". www.cbc.ca. 30 May 2006. Retrieved 17 Nov 2017.

- "Norway becomes first NATO country to draft women into military". Reuters. Reuters Staff. 14 June 2013. Retrieved 17 Nov 2017.

- Persson, Alma; Sundevall, Fia (2019-03-22). "Conscripting women: gender, soldiering, and military service in Sweden 1965–2018". Women's History Review. 28 (7): 1039–1056. doi:10.1080/09612025.2019.1596542. ISSN 0961-2025.

- Persson, Alma; Sundevall, Fia (2019-03-22). "Conscripting women: gender, soldiering, and military service in Sweden 1965–2018". Women's History Review. 28 (7): 1039–1056. doi:10.1080/09612025.2019.1596542. ISSN 0961-2025.

- Koranyi, Balazs; Fouche, Gwladys (June 14, 2014). Char, Pravin (ed.). "Norway becomes first NATO country to draft women into military". Oslo, Norway. Reuters. Archived from the original on January 28, 2015. Retrieved April 26, 2015.

- "INDEPTH: FEMALE SOLDIERS – Women in the military — international". CBC News. May 30, 2006. Archived from the original on April 4, 2015. Retrieved May 2, 2015.

- Hendrickson, Mark (2018). "Lynn Dumenil. The Second Line of Defense: American Women and World War I; Elizabeth Cobbs. The Hello Girls: America's First Women Soldiers". The American Historical Review. 123 (4): 1332–1334. doi:10.1093/ahr/rhy076.

- "Women in World War I". National Museum of American History. Retrieved 2018-11-15.

- Susan R. Sowers, Women Combatants in World War I: A Russian Case Study" (Strategy Research Project, U.S. Army War College, 2003) PDF

- Reese, Roger R. (2000). The Soviet military experience: a history of the Soviet Army, 1917–1991. Routledge. p. 17.

- "SAVED 8,000 SERBS, BUT DIED IN EFFORT: Heroic Work Of Dr. Elsie Ingles Told by Woman Just Here from the Front". New York Times. February 11, 1918.

- "SERBIAN ARMY LED BY WOMAN: DRAMATIC RETREAT THROUGH RUSSIA". South China Morning Post. April 30, 1918.

- "Milunka Savić the most awarded female combatant in the history of warfare". www.serbia.com. Retrieved 2018-08-16.

- ОШИЋ МАЛЕШЕВИЋ, Никола (2016). "Review of: Милунка Савић – витез Карађорђеве звезде и Легије части". Tokovi Istorije. 1: 223–267 – via CEEOL.

- "Women in the military". Norfolk Daily News. 8 June 2013. Retrieved 2013-10-24.

- Abramson, Larry (22 October 2013). "West Point Women: A Natural Pattern Or A Camouflage Ceiling?". NPR.org. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- Lintunen, Tiina (2014). "Women at War". The Finnish Civil War 1918: History, Memory, Legacy. Leiden: Brill Publishers. pp. 201–229. ISBN 978-900-42436-6-8.

- Lines, Lisa (May 2009). "Female combatants in the Spanish civil war: Milicianas on the front lines and in the rearguard" (PDF). Journal of International Women's Studies. 10 (4): 168–187. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- Lines, Lisa (2011). Milicianas: Women in Combat in the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939). Plymouth, UK: Lexington Press. ISBN 978-0-7391-6492-1.

- Campbell, D'Ann (1993). "Women in Combat: The World War Two Experience in the United States, Great Britain, Germany, and the Soviet Union". Journal of Military History. 57 (2): 301–323. doi:10.2307/2944060. JSTOR 2944060.

- Rani of Jhansi Regiment

- http://www.nlb.gov.sg/biblioasia/2018/04/16/warrior-women-the-rani-of-jhansi-regiment/#:~:text=

- DeGroot, G. J. (1997). "Whose Finger on the Trigger? Mixed Anti-Aircraft Batteries and the Female Combat Taboo". War in History. 4 (4): 434–453. doi:10.1177/096834459700400404.

- Schwarzkopf, 2009

- Sir Frederick Arthur Pile (bart.) (1949). Ack-ack: Britain's defence against air attack during the Second World War. Harrap. p. 193.

- Gordon Williamson, World War II German Women's Auxiliary Services (2003).

- Hagemann, Karen (2011). "Mobilizing Women for War: The History, Historiography, and Memory of German Women's War Service in the Two World Wars". Journal of Military History. 75 (4): 1055–1094.

- Campbell, D'Ann (April 1993). "Women in Combat: The World War Two Experience in the United States, Great Britain, Germany, and the Soviet Union". Journal of Military History. 57 (2): 301–323. doi:10.2307/2944060. JSTOR 2944060.

- Bronwyn Rebekah McFarland-Icke, Nurses in Nazi Germany (1999)

- Leila J. Rupp, Mobilizing Women For War: German and American Propaganda, 1939-1945 (1979)

- Smith, Susan Lynn (1999-12-01). "Women Health Workers and the Color Line in the Japanese American "Relocation Centers" of World War II". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 73 (4): 585–601. doi:10.1353/bhm.1999.0190. ISSN 1086-3176. PMID 10615767.

- Jancar, Barbara (1981). "Women in the Yugoslav National Liberation Movement: An Overview". Studies in Comparative Communism. 14 (2): 143–164. doi:10.1016/0039-3592(81)90004-1.

- Drapac, Vesna (2009). "Resistance and the Politics of Daily Life in Hitler's Europe: The Case of Yugoslavia in a Comparative Perspective". Aspasia. 3: 55–78. doi:10.3167/asp.2009.030104.

- Barbara Jancar-Webster, Women and Revolution in Yugoslavia 1941–1945 (1990)

- "Vietnam War: A timeline of U.S. entanglement". USA TODAY. Retrieved 2018-11-15.

- Library, CNN. "Vietnam War Fast Facts". CNN. Retrieved 2018-11-15.

- "Women and Social Movements in the United States, 1600-2000". linus.lmu.edu.

- "Eritrea's women fighters". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- "Statistics: Women's Service in the IDF for 2010, 25 Aug 2010". Israel Defense Forces. 25 August 2010. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- Lauren Gelfond Feldinger (21 September 2008). "Skirting history". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- "Integration of women in the IDF". Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 8 March 2009. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- "The Beginning, Women in the Early IDF". IDF Spokesperson. 7 March 2011. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- "Israel". Lcweb2.loc.gov. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- Gaza: It's a Man's War The Atlantic, 7 Aug 2014

- Fischel, Justin (24 January 2013). "Military leaders lift ban on women in combat roles". Fox. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- "UK armed forces biannual diversity statistics: 2017". www.gov.uk. 2017. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

- "Rapport d'information du Sénat N°373 : Des femmes engagées au service de la défense de notre pays" (PDF). www.senat.fr (in French). March 26, 2015.

- Försvarsmakten. "Historik". Försvarsmakten (in Swedish). Retrieved 2017-12-12.

- US Army (2013). "Support Army Recruiting". www.usarec.army.mil. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

- Defence, Government of Canada, National (2018-03-07). "National Defence | Canadian Armed Forces | Backgrounder | Women in the Canadian Armed Forces". www.forces.gc.ca. Retrieved 2018-08-16.

- Engelbrecht, Leon (2011-06-29). "Fact file: SANDF regular force levels by race & gender: April 30, 2011 | defenceWeb". www.defenceweb.co.za. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

- Goldman, Nancy (1973). "The Utilization of Women in the Military". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 406: 107–116. doi:10.1177/000271627340600110. JSTOR 1039667.

- Fisher, Max (2013-01-25). "Map: Which countries allow women in front-line combat roles?". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

- GERMAN, LINDSEY (2013). How a Century of War Changed the Lives of Women. Pluto Press. ISBN 9780745332505. JSTOR j.ctt183p28m.

- UK, Ministry of Defence (2015). "British Army: Sexual Harassment Report" (PDF). Retrieved 2017-12-11.

- Canada, Statcan [official statistics agency] (2016). "Sexual Misconduct in the Canadian Armed Forces, 2016". www.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 2017-12-11.

- Marshall, A; Panuzio, J; Taft, C (2005). "Intimate partner violence among military veterans and active duty servicemen". Clinical Psychology Review. 25 (7): 862–876. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2005.05.009. PMID 16006025.

- Stanley, Sandra Carson; Segal, Mady Wechsler (July 1988). "Military Women in NATO: An Update". Armed Forces & Society. 14 (4): 559–585. doi:10.1177/0095327x8801400405. ISSN 0095-327X.

- "Army Jobs For Women: Different Positions For Women In The Military - Militaro". militaro.com. Archived from the original on 29 March 2015. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- Miller, Gray (2019-02-22). "NCFM-Draft.pdf" (PDF). timesofsandiego.com.

- "Court Ruling Renews Debate On Women And The Draft". NPR.org. Retrieved 2019-03-28.

- Kime, Patricia (2019-02-26). "After Court Ruling, Here's What's Next for Women and the Draft". Military.com. Retrieved 2019-03-28.

- "How Roles Have Changed for Women in the Military | Norwich Online Graduate Degrees". graduate.norwich.edu. Retrieved 2018-04-20.

- Jones, Shirley Farris. "Civil War: Women Faced Danger in Roles as Spies." The Murfreesboro Post, 23 March 2008.

- "Female Soldiers in the Civil War." American Battlefield Trust, The History Channel, 15 Mar. 2018.

- Grazier, Steven M. "Mary Owens Jenkins Was Soldier in Union Army Disguised as a Man." Record-Courier, Gatehouse Ohio Media, 29 May 2017.

- Heit, Judi. "Soldier-Women of the America Civil War." Loreta Velazquez, 1 January 2011.

- Blanton, DeAnne. "Women Soldiers of the Civil War." National Archives and Records Administration, National Archives and Records Administration, 7 December 2017.

- "Women in the military". Norfolk Daily News. 8 June 2013. Retrieved 2013-10-24.

- Abramson, Larry (22 October 2013). "West Point Women: A Natural Pattern Or A Camouflage Ceiling?". NPR.org. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- Fischel, Justin (24 January 2013). "Military leaders lift ban on women in combat roles". Fox. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- "Sisters in Arms: Breaking down barriers and rising to the challenge". Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- "Women in the U.S. Army". www.army.mil. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- McGowan, Bailey (7 August 2017). "Air Force testing gender-neutral standards in San Antonio". Air Force Times. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- C. Todd Lopez (27 January 2014). "Army to open 33,000 positions to female Soldiers in April". Army News Service. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- Drohan, Ed. "CJTF Paladin offers training for female engagement team members". Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- Michaels, Jim (30 May 2015). "Women in Ranger School fail to finish grueling course". USA Today. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- Jordan, Mary; Lamothe, Dan (19 August 2015). "How did these two women become the first to complete Army Ranger School?". Washington Post. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- Lamothe, Dan (12 October 2015). "Army Ranger School has a groundbreaking new graduate: Lisa Jaster, 37, engineer and mother". Washington Post. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- "Marines' combat test period ends without female grad". www.usatoday.com. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- "Last IOC in Marine infantry experiment drops female officers". www.marinecorpstimes.com. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- Baldor, Lolita C. (7 August 2017). "Officials: Marine commandant recommends women be banned from some combat jobs". Marine Corps Times. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- Lemmon, Gayle Tzemach. "Women in combat? They've already been serving on the front lines, with heroism". latimes.com. Retrieved 2018-03-11.

- Lamothe, Dan (10 September 2015). "Marine experiment finds women get injured more frequently, shoot less accurately than men". Washington Post. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- Adamczyk, Ed (10 September 2015). "U.S. Marines study: Women in combat injured more often than men". UPI. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- Lamothe, Dan (10 September 2015). "Marine experiment finds women get injured more frequently, shoot less accurately than men". Washington Post. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

- Doan, Alesha E.; Portillo, Shannon (2017). "Not a Woman, but a Soldier: Exploring Identity Through Translocational Positionality". Sex Roles. 76 (3–4): 236–249. doi:10.1007/s11199-016-0661-7. hdl:1808/23881.

- "Coalition for Iraq & Afghanistan Veterans » Blog Archive » Female soldiers say they're up for battle". Coalitionforveterans.org. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- "Americas | Women at war face sexual violence". BBC News. 17 April 2009. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- "Rep. Jane Harman: Finally, Some Progress in Combating Rape and Assault in the Military". Huffingtonpost.com. 10 September 2008. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- Encyclopedia of Women and Gender Volume Two. Academic Press. 2001. pp. 775–776. ISBN 978-0-12-227247-9.

- Beech, Eric (6 March 2019). "Senator McSally, an Air Force veteran, says she was raped by a superior officer". Reuters. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- Surìs, Alina; Lind, Lisa; Kashner, T. Michael; Borman, Patricia D. (2007). "Mental Health, Quality of Life, and Health Functioning in Women Veterans". Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 22 (2): 179–197. doi:10.1177/0886260506295347. PMID 17202575.

- "Military Sexual Assault: The Basics". Findlaw. Retrieved 2018-11-15.

- Castro, Carl Andrew; Kintzle, Sara; Schuyler, Ashley C.; Lucas, Carrie L.; Warner, Christopher H. (2015-05-16). "Sexual Assault in the Military". Current Psychiatry Reports. 17 (7): 54. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.640.2867. doi:10.1007/s11920-015-0596-7. ISSN 1523-3812. PMID 25980511.

- Cheney, Ann M.; Reisinger, Heather Schact; Booth, Brenda M.; Mengeling, Michelle A.; Torner, James C.; Sadler, Anne G. (March 2015). "Servicewomen's Strategies to Staying Safe During Military Service". Gender Issues. 32 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1007/s12147-014-9128-8.

- Weitz, Rose (September 2015). "Vulnerable Warriors: Military Women, Military Culture, and Fear of Rape". Gender Issues. 32 (3): 164–183. doi:10.1007/s12147-015-9137-2.

- Broadbent, Lucy (9 December 2011). "Rape in the US military: America's dirty little secret | Society". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- "The Invisible War: Home". Invisiblewarmovie.com. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- Surìs, Alina; Lind, Lisa; Kashner, T. Michael; Borman, Patricia D. (2007). "SAGE Journals: Your gateway to world-class journal research". Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 22 (2): 179–197. doi:10.1177/0886260506295347. PMID 17202575.

- Castro, Carl Andrew; Kintzle, Sara; Schuyler, Ashley C.; Lucas, Carrie L.; Warner, Christopher H. (2015). "Sexual Assault in the Military". Current Psychiatry Reports. 17 (7): 54. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.640.2867. doi:10.1007/s11920-015-0596-7. PMID 25980511.

- Sadler, Anne; Booth, Brenda M.; Nielson, Deanna; Dobbeling, Bradley N. (2000). "Health Related Consequences of Physical and Sexual Violence". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 96 (3): 473–480. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.454.2108. doi:10.1016/s0029-7844(00)00919-4. PMID 10960645.

- Kip, KE; Hernandez, DF; Shuman, A; Witt, A; Diamond, DM; Davis, S; Kip, R; Abbayakumar, A; Wittenburg, T; Girling, SA; Witt, S; Rosenzweig, L (2015). "Comparison Of Accelerated Resolution Therapy (ART) For Treatment Of Symptoms Of PTSD And Sexual Trauma Between Civilian And Military Adults". Military Medicine. 180 (9): 964–971. doi:10.7205/milmed-d-14-00307. PMID 26327548.

- "Women, Leadership and the US Military: A Tale of Two Eras". 11 Aug 2010. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- "U-34 submarine, Eckernforde, 02.05.07; Freeze Frame - The Independent (London, England) | HighBeam Research". The Independent. 3 May 2007. Archived from the original on 15 May 2013. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- "Women in the military - international". Indepth. CBS News. 30 May 2006. Archived from the original on 14 October 2011. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- Commander, Submarine Group 10 Public Affairs. "Navy Welcomes Women To Serve In Submarines". Navy.mil. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- New Debate on Submarine Duty for Women Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Armed Forces Careers retrieved 11 August 2007

- Navy Office of Information, "Women on Submarines", Rhumblines, 5 October 2009.

- Commander, Submarine Forces Public Affairs. "Navy Policy Will Allow Women To Serve Aboard Submarines". Navy.mil. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- "Royal Navy gets first female submariners". BBC. 5 May 2014. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- "Argentina Jews honor female submarine officer lost at sea". Retrieved 2018-08-16.

- "Día de la Mujer: recordaron con un sentido homenaje a Eliana Krawczyk, la submarinista desaparecida en el ARA San Juan - MisionesOnline". MisionesOnline (in Spanish). 2018-03-08. Retrieved 2018-08-16.

- "Première patrouille de SNLE avec quatre femmes à bord". Ministère des Armées. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- Groizeleau, Vincent (19 July 2018). "Les Premières Femmes de la Sous-marinade Française". Mer et Marine. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- "Vrouwen gaan voor het eerst mee in onderzeeër, dus komen er gordijnen en douchedeurtjes voor de privacy" (in Dutch). 9 October 2018.

- "First woman enters Japan's submarine academy after end of restrictions". The Japan Times. January 22, 2020.

The first female student was admitted to Japan’s national naval submarine academy Wednesday after the end of a ban on women on the country’s submarines. Risa Takenouchi, 26, entered the academy in Hiroshima along with about 20 men, after the Maritime Self-Defense Force overturned previous restrictions.

- Jennifer M. Silva (2008). "A New Generation of Women? How Female ROTC Cadets Negotiate the Tension between Masculine Military Culture and Traditional Femininity". Social Forces. 87 (2): 937–960. doi:10.1353/sof.0.0138. JSTOR 20430897.

- Matthews, M.D; Ender, Morten G.; Laurence, J.H.; Rohall, D.E. (2009). "Role of group affiliation and gender attitudes toward women in the military". Military Psychology. 21 (2): 241–251. doi:10.1080/08995600902768750.

- https://www.marinecorpstimes.com/news/your-marine-corps/2018/10/11/broken-feet-and-bruised-egos-male-marines-take-brunt-of-injuries-at-infantry-officer-course/

- Smith, Bruce. "86% of women fail Marines' combat jobs test". thestate. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

Further reading

Bibliography

- Fasting, Kari and Trond Svela Sand eds., (2010). "Gender and Military Issues - A Categorized Research Bibliography." Moving Soldiers - Soldaten i bevegelse 01/2010. ISSN 1891-8751.

- Sand, Trond Svela and Kari Fasting eds., (2012), "Gender and Military Issues in the Scandinavian Countries - A Categorized Research Bibliography." Moving Soldiers - Soldaten i bevegelse 01/2012. ISSN 1891-8751.

- Brownson, Connie (2014). ""Rejecting Patriarchy for Equivalence in the US Military A Response to Anthony King's "Women Warriors: Female Accession to Ground Combat"". Armed Forces & Society. 40 (4): 765–788. doi:10.1177/0095327X14523957.

History

- Cook, Bernard, ed, (2006). Women and War: Historical Encyclopedia from Antiquity to the Present.

- Elshtain, Jean Bethke. Women and War (1995)

- Elshtain Jean, and Sheila Tobias, eds., Women, Militarism, and War (1990),

- Goldman, Nancy Loring ed. (1982). Female Soldiers--Combatants or Noncombatants? Historical and Contemporary Perspectives.

- Goldstein, Joshua S. . War and Gender: How Gender Shapes the War System and Vice Versa (2003), psychology perspective

- Hacker, Barton C. and Margaret Vining, eds. A Companion to Women's Military History (2012) 625pp; articles by scholars covering a very wide range of topics

- Hall, Richard H. Women on the Civil War battlefront (University Press of Kansas 2006).

- Lines, Lisa (2011). Milicianas: Women in Combat in the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939). Plymouth, UK: Lexington Press. ISBN 978-0-7391-6492-1.

- Jones, David. Women Warriors: A History, Brassey's, 1997

- Pennington, Reina, (2003). Amazons to Fighter Pilots: A Biographical Dictionary of Military Women.

- Salmonson, Jessica Amanda (1991). The Encyclopedia of Amazons: Women Warriors from Antiquity to the Modern Era. Paragon House. ISBN 978-1-55778-420-9.

World War II

- Biddiscombe, Perry, (2011). "Into the Maelstrom: German Women in Combat, 1944-45," War & Society (2011), 30#1 pp 61–89

- Bidwell, Shelford. The Women's Royal Army Corps (London, 1977) on Britain

- Campbell, D'Ann. Women at War with America: Private Lives in a Patriotic Era (Harvard University Press, 1984). on WW2

- Campbell, D'Ann. "Servicewomen of World War II", Armed Forces and Society (Win 1990) 16: 251–270. statistical study based on interviews

- Campbell, D'Ann. "Women in Combat: The World War Two Experience in the United States, Great Britain, Germany, and the Soviet Union" Journal of Military History (April 1993), 57:301-323. online edition JSTOR 2944060

- Cottam, K. Jean Soviet Airwomen in Combat in World War II (Manhattan, KS: Military Affairs/Aerospace Historian Publishing, 1983)

- DeGroot G.J. "Whose Finger on the Trigger? Mixed Anti-Aircraft Batteries and the Female Combat Taboo," War in History, Volume 4, Number 4, December 1997, pp. 434–453

- Dombrowski, Nicole Ann. Women and War in the Twentieth Century: Enlisted With or Without Consent (1999)

- Dominé, Jean-François, (2008). Les femmes au combat; l'arme féminine de la France pendant la Seconde Guerre Mondiale

- Hagemann, Karen (2011). "Mobilizing Women for War: The History, Historiography, and Memory of German Women's War Service in the Two World Wars". Journal of Military History. 75 (3): 1055–1093.

- Harfield, Alan (2005). "The Women's Auxiliary Corps (India)". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 83 (335): 243–254.

- Krylova, Anna, (2010). Soviet Women in Combat: A History of Violence on the Eastern Front.

- Morton, Alison. Military or civilians? The curious anomaly of the German Women's Auxiliary Services during the Second World War. 2012. ASIN B007JUR408

- Markwick, Roger D. (2008). "A Sacred Duty": Red Army Women Veterans Remembering the Great Fatherland War, 1941–1945," Australian Journal of Politics & History, (2008), 54#3 pp. 403-420.

- Maubach, Franka; Satjukow, Silke. (2009). "Zwischen Emanzipation und Trauma: Soldatinnen im Zweiten Weltkrieg (Deutschland, Sowjetunion, USA)" Historische Zeitschrift, (April 2009), Vol. 288 Issue 2, pp 347–384

- Merry, Lois K, (2010). Women Military Pilots of World War II: A History with Biographies of American, British, Russian and German Aviators.

- Pennington, Reina, (2007). Wings, Women & War: Soviet Airwomen in World War II Combat

- Pennington, Reina, (2010). "Offensive Women: Women in Combat in the Red Army in the Second World War" Journal of Military History, July 2010, Vol. 74 Issue 3, p775-820

- Pierson, Ruth Roach. (1986). They're Still Women After All: The Second World War and Canadian Womanhood.

- McBryde, Brenda. (1985). Quiet Heroines: Story of the Nurses of the Second World War, on British

- Sarnecky, Mary T. (1999). A History of the U.S. Army Nurse Corps

- Schwarzkopf, Jutta (2009). "Combatant or Non-Combatant? The Ambiguous Status of Women in British Anti-Aircraft Batteries during the Second World War". War & Society. 28 (2): 105–131. doi:10.1179/072924709793054642.

- Toman, Cynthia, (2007). An Officer and a Lady: Canadian Military Nursing and the Second World War.

- Treadwell, Mattie E. (1954). United States Army in World War II: Special Studies: The Women's Army Corps. the standard history; part of the Army "Green series" online free

- Williamson, Gordon, (2003). World War II German Women's Auxiliary Services

Recent

- Campbell, D'Ann. (2012) "Almost Integrated? American Servicewomen and Their International Sisters Since World War II" in A Companion to Women's Military History ed by Barton C. Hacker and Margaret Vining pp 291–330

- Carreiras, Helena. Gender and the military: women in the armed forces of Western democracies (New York: Routledge, 2006)

- Carreiras, Helena and Gerhard Kammel (eds.) Women in the Military and in Armed Conflict (2008) excerpt and text search

- Dandeker, Christopher, and Mady Wechsler Segal. "Gender integration in armed forces: recent policy developments in the United Kingdom" Armed Forces & Society 23#1 (Fall 1996): 29–47.

- Eitelberg, Mark J., Aten, Kathryn J., and Smith, Michael K. Comparison of Women's Policies in Six International Navies (2014). NPS-GSBPP-15-001. Monterey, CA: Naval Postgraduate School.

- Eulriet, Irène. Women and the military in Europe: comparing public cultures (New York: Palgrave Macmillan. 2009)

- Frampton, James Scott The Influence of Attitudes and Morale on the Performance of Active-Duty United States Marine Corps Female Security Guards (2011)

- Frank, Nathaniel et al. eds. Gays in foreign militaries 2010: A global primer (Santa Barbara, CA: Palm Center, 2010)

- Garcia, Sarah (1999). "Military women in the NATO armed forces". Minerva: Quarterly Report on Women and the Military. 17 (2): 33–82.

- Gill, Ritu; Febbraro, Angela R. (2013). "Experiences and perceptions of sexual harassment in the Canadian Forces Combat Arms". Violence Against Women. 19 (2): 269–287. doi:10.1177/1077801213478140. PMID 23443902.

- Goldman, Nancy. "The Changing Role of Women in the Armed Forces." American Journal of Sociology 1973 78(4): 892–911. ISSN 0002-9602 JSTOR 2776610

- Herbert, Melissa S. Camouflage Isn't Only for Combat: Gender, Sexuality, and Women in the Military (New York U. Press, 1998)

- Holm, Jeanne M. (1993). Women in the Military: An Unfinished Revolution.; women from the United States

- Lemmon, Gayle Tzemach. Ashley's War: The Untold Story of a Team of Women Soldiers on the Special Ops Battlefield (HarperCollins, 2015) American women

- Skaine, Rosemarie. Women at War: Gender Issues of Americans in Combat. McFarland, 1999.

- United States Presidential Commission on the Assignment of Women. (1993) 'Report on the Presidential Commission on the Assignment of Women

Middle East

- Holmstedt, Kirsten. Band of Sisters: American Women at War in Iraq (2007) excerpt and text search

- Holmstedt, Kirsten. "The Girls Come Marching Home"

- Wise, James E. and Scott Baron. Women at War: Iraq, Afghanistan, and Other Conflicts (2006)

Social science studies

- Archer, Emerald M (2013). "The Power of Gendered Stereotypes in the US Marine Corps". Armed Forces & Society. 39 (2): 359–391. doi:10.1177/0095327x12446924.

- Booth, Bradford (2003). "Contextual Effects of Military Presence on Women's Earnings". Armed Forces & Society. 30: 25–51. doi:10.1177/0095327x0303000102.

- Cooney; et al. (2003). "Racial Differences in the Impact of Military Service on the Socioeconomic Status of Women Veterans". Armed Forces & Society. 30: 53–85. doi:10.1177/0095327x0303000103.

- Dar, Yechezkel; Kimhi, Shaul (2004). "Youth in the Military: Gendered Experiences in the Conscript Service in the Israeli Army". Armed Forces & Society. 30 (3): 433–459. doi:10.1177/0095327x0403000306.

- Iskra, Darlene (2007). "Attitudes toward Expanding Roles for Navy Women at Sea: Results of a Content Analysis". Armed Forces & Society. 33 (2): 203–223. doi:10.1177/0095327x06287883.

- Mitchell, Brian. 1998. Women in the Military: Flirting with Disaster. Washington, D.C.: Regnery Publishing. xvii, 390 ISBN 0-89526-376-9

- Moore, Brenda (1991). "African American Women in the U.S. Military". Armed Forces & Society. 17 (3): 363–384. doi:10.1177/0095327x9101700303.

External links

.jpg)