Communal conflicts in Nigeria

Communal conflicts in Nigeria[3] can be divided into two broad categories:[4]

- Ethno-religious conflicts, attributed to actors primarily divided by cultural, ethnic, or religious communities and identities, such as instances of religious violence between Christian and Muslim communities.

- Herder–farmer conflicts, typically involving disputes over land and/or cattle between herders (in particular the Fulani and Hausa) and farmers (in particular the Adara, Berom, Tiv and Tarok).

| Communal conflicts in Nigeria | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

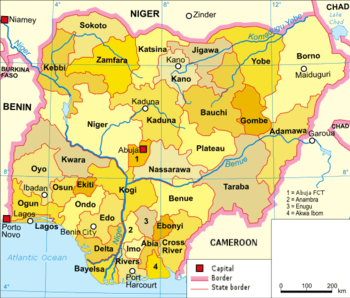

Map of the 36 States of Nigeria | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||

| Christians | Muslims |

| ||||||

| Adara, Berom, Jukun, Tiv and Tarok farmers | Fulani and Hausa herders |

Nigeria Police Force | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | ||||||||

| 16,000+ people killed since 1998[1][2] | ||||||||

The most impacted states are those of the Nigerian Middle Belt like Benue, Taraba and Plateau.[5] Violence has reached two peaks in 2004 and 2011 with around 2,000 fatalities those years.[6] It resulted in more than 700 fatalities in 2015 alone.[2]

Causes

Climate change played a major role in the migration of Fulani herdsmen.

African countries have been affected the most by climate change globally. This notion has contributed to the migration of Fulani Herdsmen from the North towards southwest Nigeria. As observed from a "Push and pull" model, desertification, landslides, droughts, pollution, sand storms, and diseases that have all transpired from climatic changes have led Fulani Herdsmen to leave their communities. This is mostly due to droughts which timespans have persisted longer than anticipated, such as the evaporation of Lake Chad. Moreover, diseases have developed from climatic conditions and is killing the animals of these herdsmen. Thus, many Fulani's, also known as "the Bororos", are inclined to migrate south where there is improved vegetation, weather conditions, market opportunities, and hopefulness.[7]

Herder–farmer conflicts

Since the Fourth Nigerian Republic's founding in 1999, farmer-herder violence has killed thousands of people and displaced tens of thousands more. Insecurity and violence have led many populations to create self-defence forces and ethnic militias, which have engaged in further violence. The majority of farmer–herder clashes have occurred between Muslim Fulani herdsmen and Christian peasants, exacerbating ethnoreligious hostilities.[8] This violence stems from the relationship between the Bororo Fulani and the Yoruba farmers. Prior to this, the Fulani people had migrated into the southwestern Nigeria region centuries ago. In fact, in the 18th century, three different groups of Fulani had migrated to the city of Iseyin. These groups consisted of the Bangu, Sokoto, and Bororo Fulani. Out of these three groups, the Bororo Fulani in particular were the group to separate themselves from the Yoruba farmers. Meanwhile, the Bangu and Sokoto had developed a working relationship with the Yoruba people of Nigeria.[9] Through this bond, they profited off of each other from the by products of their cattle and agriculture. The Fulani people would trade any commodities they extracted from their cattle to the Yoruba's for their crops. However, the migration of the Bororo Fulani shifted this relationship as they were perceived to be more aggressive than the settled Fulani. This difference was further exacerbated as they did not speak the native Yoruba language unlike the settled Fulani people who did. As the Bororo Fulani pastoralists integrated into this region the cattle they owned started damaging Yoruba farmers' crops and plants. This led to friction to become quite common among these two groups. One case that can be observed was when additional wreckage was pressed into farmers in the city of Iseyin after a group of Bororo Fulani were exiled from the city of Oyo and migrated there in 1998.[10]

Another conflict the Bororo Fulani have been involved with was in 1804 when the Fulani had a Holy War between those who identified as Muslim and resonated with the Hausas and those that were still associated with the Pagan tribes.[11] The war took place in the northern region of Nigeria. This war led to a dichotomy of two groups of the Fulani. One group amalgamated with the Hausa people and are essentially integrated as Hausas while holding positions of wealth and power. The other group kept their pastoral ways intact and did not intermesh with any other tribes. This is what eventually became the Bororo Fulani which means the Bush or Cow Fulani.

Currently, the conflict between Fulani herders and other Nigerian farmers have intensified.[12] From 2011 to 2016, roughly 2,000 people have been killed and tens of thousands have been displaced. This is partly due to the rise of jihadist groups, such as Boko Haram. Their presence has jeopardized many herders and farmers that graze in Northern Nigeria. The government has made little efforts to intervene and create schemes to alleviate this conflict. Hence, herders and farmers take it upon themselves to solve the conflicts existing within the community which invigorates conflict.

Abet Fulani Herders

The Abet, also known as the Kachichere, are another subgroup of the Fulani.[13] They live in the Abet region of Nigeria after they migrated there in the 18th century. They live in a region for approximately 3 to 5 years before moving another few kilometers within the Abet. Once they establish a homestead, their herds graze within a 3-mile radius. The reason they prefer to graze in the Abet is due to the favorable conditions it holds for their cattle. This stems from the dry season coinciding with the peak of cow fertility and the production of milk. Furthermore, it is easier to herd animals in these open land spaces rather than in condense areas replete of bushes. For land rights in this region, Fulani families may be given rights to parts of the land through customary structures. Thus, land is distributed from Chiefs or those in charge of the villages that these fields reside in.

Other examples

Additional instances of ethnic violence in Nigeria exist;[14][15] these are often urban riots or such, for example the Yoruba-Hausa disturbances in Lagos,[16][17] the Igbo massacre of 1966 or the clashes between the Itsekiri and the Ijaw in Delta state. Others are land disputes between neighbours, such as clashes between Ile-Ife and Modakeke in the late 1990s[18] and in Ebonyi State in 2011.[19]

See also

References

- "Social Violence Data Table". Connect SAIS Africa. Archived from the original on 2015-06-29. Retrieved 2015-09-09.

- "ACLED Realtime data 2015". Archived from the original on 2015-10-31.

- "Backgrounder: Communal conflicts in Nigeria". UCDP. 21 June 2012. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- "Nigeria Social Violence Project Summary" (PDF). Connect SAIS Africa. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-06-29.

- "KILLINGS IN BENUE, PLATEAU AND TARABA STATES". Archived from the original on 2015-07-27. Retrieved 2015-09-09.

- "Social violence in Nigeria". Connect SAIS Africa. Archived from the original on 2015-06-26. Retrieved 2015-09-09.

- Folami, Olakunle Michael; Folami, Adejoke Olubimpe (January 2013). "Climate Change and Inter-Ethnic Conflict in Nigeria". Peace Review. 25 (1): 104–110. doi:10.1080/10402659.2013.759783. ISSN 1040-2659.

- "Farmer-Herder Clashes Amplify Challenge for Beleaguered Nigerian Security". IPI Global Observatory. 16 July 2015.

- Adebayo, A. G. (1991). "Of Man and Cattle: A Reconsideration of the Traditions of Origin of Pastoral Fulani of Nigeria". History in Africa. 18: 1–21. doi:10.2307/3172050. ISSN 0361-5413. JSTOR 3172050.

- Olaniyi, Rasheed Oyewole (2014-02-27). "Bororo Fulani Pastoralists and Yoruba Farmers' Conflicts in the Upper Ogun River, Oyo State Nigeria, 1986–2004". Journal of Asian and African Studies. 50 (2): 239–252. doi:10.1177/0021909614522948. ISSN 0021-9096.

- Ibrahim, Mustafa B. (April 1966). "The Fulani - A Nomadic Tribe in Northern Nigeria". African Affairs. 65 (259): 170–176. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a095498. ISSN 1468-2621.

- "Double-edged Sword: Vigilantes in African Counter-insurgencies". Crisis Group. 2017-09-07. Retrieved 2019-05-13.

- Waters-Bayer, Ann; Bayer, Wolfgang (1994). "Corning to Terms. Interactions between Immigrant Fulani Cattle-Keepers and Indigenous Farmers in Nigeria's Subhumid Zone". Cahiers d'études africaines. 34 (133): 213–229. doi:10.3406/cea.1994.2048. ISSN 0008-0055.

- "An Evaluation of the Causes and Efforts Adopted in Managing the Ethnic Conflicts, Identity and Settlement Pattern among the Different Ethnic Groups in Warri, Delta State, Nigeria" Archived 2017-09-19 at the Wayback Machine, Agbegbedia Oghenevwoke Anthony. International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN (Online): 2319-7064 Volume 3 Issue 4, April 2014.

- ORUMIE S. T. (May 2008). "2 NIGER DELTA DEVELOPMENT COMMISION (NDDC) AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE OIL PRODUCING COMMUNITIES: A CASE STUDY OF RIVERS STATE" (PDF). University of Nigeria, Nsukka. University of Nigeria, Nsukka. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 August 2017. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- NIGERIA: Special Report on Ethnic Violence Archived 2016-10-17 at the Wayback Machine UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA - AFRICAN STUDIES CENTER.

- "Lagos calm after city centre riots". BBC Online. BBC. 2000-10-18. Archived from the original on 2018-05-19. Retrieved 2007-03-03.

- Ife Modakeke Clash: Guess What Ooni’s Planning Archived 2016-08-16 at the Wayback Machine Michael Abimboye, naij.com Archived 2017-10-26 at the Wayback Machine

- Nigeria: 'at least 50 killed' in communal clashes. Archived 2018-03-12 at the Wayback Machine The Telegraph, 11:28AM GMT 01 Jan 2012.

Suggested reading

- Maier, Karl (December 18, 2002). This House Has Fallen: Nigeria in Crisis (illustrated, reprint ed.). Basic Books. ISBN 0813340454.