Women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the mid-19th century, aside from the work being done by women for broad-based economic and political equality and for social reforms, women sought to change voting laws to allow them to vote.[1] National and international organizations formed to coordinate efforts towards that objective, especially the International Woman Suffrage Alliance (founded in 1904 in Berlin, Germany), as well as for equal civil rights for women.[2]

Many instances occurred in recent centuries where women were selectively given, then stripped of, the right to vote. The first province in the world to award and maintain women’s suffrage continuously, was Wyoming Territory in 1869, and the first sovereign nation was Norway in 1913. In the years after 1869, a number of provinces held by the British and Russian empires conferred women’s suffrage, and some of these became sovereign nations at a later point, like New Zealand, Australia, and Finland. Women who owned property gained the right to vote in the Isle of Man in 1881, and in 1893, women in the then British colony of New Zealand were granted the right to vote. In Australia, women progressively gained the right to vote between 1894 and 1911 (federally in 1902).[3] Prior to independence, the Russian Grand Duchy of Finland women were the first in the world to gain racially-equal suffrage, with both the right to vote and to stand as candidates in 1906.[4][5][6] Most major Western powers extended voting rights to women in the interwar period, including Canada (1917), Britain and Germany (1918), Austria and the Netherlands (1919) and the United States (1920). Notable exceptions in Europe were France, where women could not vote until 1944, Greece (1952), and Switzerland (1971). Now that Saudi Arabia has granted voting rights to women (2015), women can vote in every country that has elections.[7]

Leslie Hume argues that the First World War changed the popular mood:

The women's contribution to the war effort challenged the notion of women's physical and mental inferiority and made it more difficult to maintain that women were, both by constitution and temperament, unfit to vote. If women could work in munitions factories, it seemed both ungrateful and illogical to deny them a place in the voting booth. But the vote was much more than simply a reward for war work; the point was that women's participation in the war helped to dispel the fears that surrounded women's entry into the public arena.[8]

Extended political campaigns by women and their supporters have generally been necessary to gain legislation or constitutional amendments for women's suffrage. In many countries, limited suffrage for women was granted before universal suffrage for men; for instance, literate women or property owners were granted suffrage before all men received it. The United Nations encouraged women's suffrage in the years following World War II, and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (1979) identifies it as a basic right with 189 countries currently being parties to this Convention.

History

In ancient Athens, often cited as the birthplace of democracy, only adult, male citizens who owned land were permitted to vote. Through subsequent centuries, Europe was generally ruled by monarchs, though various forms of parliament arose at different times. The high rank ascribed to abbesses within the Catholic Church permitted some women the right to sit and vote at national assemblies – as with various high-ranking abbesses in Medieval Germany, who were ranked among the independent princes of the empire. Their Protestant successors enjoyed the same privilege almost into modern times.[9]

Marie Guyart, a French nun who worked with the First Nations peoples of Canada during the seventeenth century, wrote in 1654 regarding the suffrage practices of Iroquois women, "These female chieftains are women of standing amongst the savages, and they have a deciding vote in the councils. They make decisions there like the men, and it is they who even delegated the first ambassadors to discuss peace."[10] The Iroquois, like many First Nations peoples in North America, had a matrilineal kinship system. Property and descent were passed through the female line. Women elders voted on hereditary male chiefs and could depose them.

The emergence of modern democracy generally began with male citizens obtaining the right to vote in advance of female citizens, except in the Kingdom of Hawai'i, where universal suffrage was introduced in 1840 without mention of sex; however, a constitutional amendment in 1852 rescinded female voting and put property qualifications on male voting.[11]

In Sweden, conditional women's suffrage was in effect during the Age of Liberty (1718–1772).[13] Other possible contenders for first "country" to grant women suffrage include the Corsican Republic (1755), the Pitcairn Islands (1838), the Isle of Man (1881), and Franceville (1889–1890), but some of these operated only briefly as independent states and others were not clearly independent.

In 1756, Lydia Taft became the first legal woman voter in colonial America. This occurred under British rule in the Massachusetts Colony.[14] In a New England town meeting in Uxbridge, Massachusetts, she voted on at least three occasions.[15] Unmarried white women who owned property could vote in New Jersey from 1776 to 1807.

In the 1792 elections in Sierra Leone, then a new British colony, all heads of household could vote and one-third were ethnic African women.[16]

19th century

The female descendants of the Bounty mutineers who lived on Pitcairn Islands could vote from 1838. This right was transferred after they resettled in 1856 to Norfolk Island (now an Australian external territory).[17]

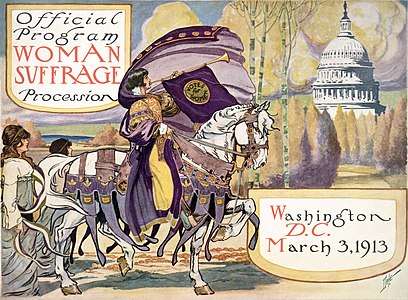

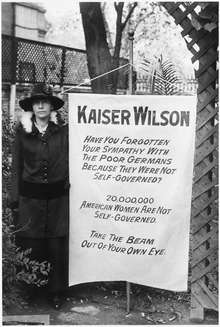

The seed for the first Woman's Rights Convention in the United States in Seneca Falls, New York was planted in 1840, when Elizabeth Cady Stanton met Lucretia Mott at the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London. The conference refused to seat Mott and other women delegates from the U.S. because of their sex. In 1851, Stanton met temperance worker Susan B. Anthony, and shortly the two would be joined in the long struggle to secure the vote for women in the U.S. In 1868 Anthony encouraged working women from the printing and sewing trades in New York, who were excluded from men's trade unions, to form Working Women's Associations. As a delegate to the National Labor Congress in 1868, Anthony persuaded the committee on female labor to call for votes for women and equal pay for equal work. The men at the conference deleted the reference to the vote.[18] In the U.S.A., women in the Wyoming Territory were permitted to both vote and stand for office in 1869.[19] Subsequent American suffrage groups often disagreed on tactics, with the National American Woman Suffrage Association arguing for a state-by-state campaign and the National Woman's Party focusing on an amendment to the U.S. Constitution.[20]

The 1840 constitution of the Kingdom of Hawaii established a House of Representatives, but did not specify who was eligible to participate in the election of it. Some academics have argued that this omission enabled women to vote in the first elections, in which votes were cast by means of signatures on petitions; but this interpretation remains controversial. The second constitution of 1852 specified that suffrage was restricted to males over twenty years-old.[11]

In 1881 the Isle of Man, an internally self-governing dependent territory of the British Crown, enfranchised women property owners. With this it provided the first action for women's suffrage within the British Isles.[17]

The Pacific commune of Franceville (now Port Vila, Vanuatu), maintained independence from 1889 to 1890, becoming the first self-governing nation to adopt universal suffrage without distinction of sex or color, although only white males were permitted to hold office.[21]

For countries that have their origins in self-governing colonies but later became independent nations in the 20th century, the Colony of New Zealand was the first to acknowledge women's right to vote in 1893, largely due to a movement led by Kate Sheppard. The British protectorate of Cook Islands rendered the same right in 1893 as well.[22] Another British colony in the same decade, South Australia, followed in 1894, enacting laws which not only extended voting to women, but also made women eligible to stand for election to its parliament at the next vote in 1895.[12] This was the second province to do so after the Wyoming Territory in North America.

20th century

The newly federated Australian Federal Parliament passed laws to permit voting and standing for election, to adult women for National elections from 1902 (with the exception of Aboriginal women in some states).[23].

The first place in Europe to introduce women's suffrage was the Grand Duchy of Finland in 1906, and it also became the first place in continental Europe to implement racially-equal suffrage for women.[4][5] As a result of the 1907 parliamentary elections, Finland's voters elected 19 women as the first female members of a representative parliament. This was one of many self-governing actions in the Russian autonomous province that led to conflict with the Russian governor of Finland, ultimately leading to the creation of the Finnish nation in 1917.

In the years before World War I, women in Norway also won the right to vote. During WWI, Denmark, Canada, Russia, Germany, and Poland also recognized women's right to vote. The Representation of the People Act 1918 saw British women over 30 gain the vote. Dutch women won the vote in 1919, and American women on 26 August 1920 with the passage of the 19th Amendment (the Voting Rights Act of 1965 secured voting rights for racial minorities). Irish women won the same voting rights as men in the Irish Free State constitution, 1922. In 1928, British women won suffrage on the same terms as men, that is, for ages 21 and older. The suffrage of Turkish women was introduced in 1930 for local elections and in 1934 for national elections.

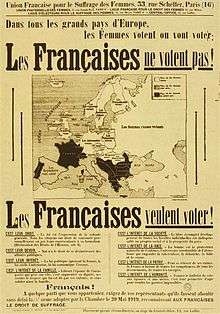

By the time French women were granted the suffrage in July 1944 by Charles de Gaulle's government in exile, by a vote of 51 for, 16 against,[24] France had been for about a decade the only Western country that did not at least allow women's suffrage at municipal elections.[25]

Voting rights for women were introduced into international law by the United Nations' Human Rights Commission, whose elected chair was Eleanor Roosevelt. In 1948 the United Nations adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; Article 21 stated: "(1) Everyone has the right to take part in the government of his country, directly or through freely chosen representatives. (3) The will of the people shall be the basis of the authority of government; this will shall be expressed in periodic and genuine elections which shall be by universal and equal suffrage and shall be held by secret vote or by equivalent free voting procedures."

The United Nations General Assembly adopted the Convention on the Political Rights of Women, which went into force in 1954, enshrining the equal rights of women to vote, hold office, and access public services as set out by national laws. One of the most recent jurisdictions to acknowledge women's full right to vote was Bhutan in 2008 (its first national elections).[26] Most recently, in 2011 King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia let women vote in the 2015 local elections and be appointed to the Consultative Assembly.

Suffrage movements

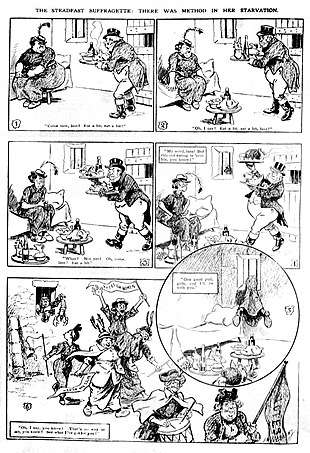

The suffrage movement was a broad one, made up of women and men with a wide range of views. In terms of diversity, the greatest achievement of the twentieth-century woman suffrage movement was its extremely broad class base.[27] One major division, especially in Britain, was between suffragists, who sought to create change constitutionally, and suffragettes, led by English political activist Emmeline Pankhurst, who in 1903 formed the more militant Women's Social and Political Union.[28] Pankhurst would not be satisfied with anything but action on the question of women's enfranchisement, with "deeds, not words" the organisation's motto.[29][30]

Throughout the world, the Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), which was established in the United States in 1873, campaigned for women's suffrage, in addition to ameliorating the condition of prostitutes.[31][32] Under the leadership of Frances Willard, "the WCTU became the largest women's organization of its day and is now the oldest continuing women's organization in the United States."[33]

There was also a diversity of views on a "woman's place". Suffragist themes often included the notions that women were naturally kinder and more concerned about children and the elderly. As Kraditor shows, it was often assumed that women voters would have a civilizing effect on politics, opposing domestic violence, liquor, and emphasizing cleanliness and community. An opposing theme, Kraditor argues, held that women had the same moral standards. They should be equal in every way and that there was no such thing as a woman's "natural role".[34][35]

For black women, achieving suffrage was a way to counter the disfranchisement of the men of their race.[36] Despite this discouragement, black suffragists continued to insist on their equal political rights. Starting in the 1890s, African American women began to assert their political rights aggressively from within their own clubs and suffrage societies.[37] "If white American women, with all their natural and acquired advantages, need the ballot," argued Adella Hunt Logan of Tuskegee, Alabama, "how much more do black Americans, male and female, need the strong defense of a vote to help secure their right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness?"[36]

Timeline

| Country | Year women first granted suffrage at national level | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1963 | ||

| 1945 | Albanian women voted for the first time in the 1945 election. | |

| 1962 | In 1962, on its independence from France, Algeria granted equal voting rights to all men and women. | |

| 1970 | ||

| 1975 | ||

| 1947[39] | On September 23, 1947 the Female Enrollment Act (number 13,010) was enacted in the government of Juan Perón | |

| 1917 (by application of the Russian legislation) 1919 March (by adoption of its own legislation)[40] |

||

| Colony of South Australia 1894, Colony of Western Australia 1899, the remaining Australian states in 1902 | Indigenous Australian women (and men) were granted the vote in South Australia in 1895, but this right was revoked in 1902 for any Aboriginal person not already enrolled. Indigenous Australians were not given the right to vote in all states until 1962.[41][42] | |

| 1918 | The Electoral Code was changed in December 1918.[43] First election was in February 1919.[44] | |

| 1918 | Azerbaijan was the first Muslim-majority country to enfranchise women.[45] | |

| 1960 | ||

| 2002 | No elections were held in Bahrain prior to 2002 since 1973. | |

| 1971 (upon its independence) | ||

| 1950 | ||

| 1951 | ||

| 1951 | ||

| 1919 | ||

| 1919/1948 | Was granted in the constitution in 1919, for communal voting. Suffrage for the provincial councils and the national parliament only came in 1948. | |

| 1954 | ||

| 1956 | ||

| 1944 | ||

| 1953 | ||

| 1938/1952 | Limited women's suffrage in 1938 (only for literate women and those with a certain level of income). On equal terms with men since 1952.[46] | |

| 1965 | ||

| 1932 | ||

| 1959 | Elections currently suspended since 1962 and 1965. Both men and women have voting rights only for local elections.[47] | |

| 1937/1944 | Married women (and by default widowed women) gained the right to vote on 18 January 1937 in local elections, but could not run for office. Single women were excluded from voting. Full voting rights were bestowed by the communist regime in September 1944 and reaffirmed by an electoral law reform on 15 June 1945.[48] | |

| 1958 | ||

| 1922 | ||

| 1961 | ||

| 1955 | ||

| 1946 | ||

| 1917–1919 for most of Canada; Prince Edward Island in 1922; Newfoundland in 1925; Quebec in 1940; 1960 for Aboriginal People without requiring them to give up their status as before | To help win a mandate for conscription during World War I, the federal Conservative government of Robert Borden granted the vote in 1917 to war widows, women serving overseas, and the female relatives of men serving overseas. However, the same legislation, the Wartime Elections Act, disenfranchised those who became naturalized Canadian citizens after 1902. Women over 21 who were "not alien-born" and who met certain property qualifications were allowed to vote in federal elections in 1918. Women first won the vote provincially in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta in 1916; British Columbia and Ontario in 1917; Nova Scotia in 1918; New Brunswick in 1919 (women could not run for New Brunswick provincial office until 1934); Prince Edward Island in 1922; Newfoundland in 1925 (which did not join Confederation until 1949); and Quebec in 1940.[49]

Aboriginal men and women were not given the right to vote until 1960; previously, they could only vote if they gave up their treaty status. It was not until 1948, when Canada signed the UN's Universal Declaration of Human Rights, that it was forced to examine the issue of discrimination against Aboriginal people.[50] | |

| 1975 (upon its independence) | ||

| 1957 | ||

| 1986 | ||

| 1958 | ||

| 1949 | From 1934–1949, women could vote in local elections at 25, while men could vote in all elections at 21. In both cases, literacy was required. | |

| 1947 | ||

| 1954 | ||

| 1956 | ||

| 1967 | ||

| 1963 | ||

| 1893 | ||

| 1949 | ||

| 1952 | ||

| 1934 | ||

| 1960 | ||

| 1920 | ||

| 1908 at local elections, 1915 at national parliamentary elections | ||

| 1946 | ||

| 1942 | ||

| 1929/1967 | Despite that Ecuador granted women suffrage in 1929, which was earlier than most independent countries in Latin America (except for Uruguay, which granted women suffrage in 1917), differences between men's and women's suffrage in Ecuador were only removed in 1967 (before 1967 women's vote was optional, while that of men was compulsory; since 1967 it is compulsory for both sexes).[46][51] | |

| 1956 | ||

| 1939/1950 | Women obtained in 1939 suffrage with restrictions requiring literacy and a higher age. All restrictions were lifted in 1950 allowing women to vote, but women obtained the right to stand for elections only in 1961.[52] | |

| 1963 | Effectively a one-party state under the Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea since 1987; elections in Equatorial Guinea are not considered to be free or fair. | |

| 1917 | ||

| 1955 | ||

| 1963 | ||

| 1906 | Women retained the right to vote when Finland gained its independence from Russia in 1917. | |

| 1944 | French women were disenfranchised at all levels before 1944. | |

| 1956 | ||

| 1960 | ||

| 1918 | ||

| 1918 | ||

| 1954 | ||

| 1930 (Local Elections, Literate Only), 1952 (Unconditional) | ||

| 1945/1965 | Women could vote from 1945, but only if literate. Restrictions on women's suffrage were lifted in 1965.[53] | |

| 1958 | ||

| 1977 | ||

| 1953 | ||

| 1950 | ||

| 1840-1852 | Universal suffrage was established in 1840, which meant that women could vote. Opposition resulted in a specific denial of women's suffrage in the 1852 constitution. | |

| 1955 | ||

| 1949 | ||

| 1919 (partial) 1945 (full) |

After 1919 men could vote from the age of 24 while women only gained the right to vote from the age of 30. There were also educational and economical criteria set for both genders, but all criteria were higher for women. After 1945 both men and women gained universal suffrage from the age of 20. | |

| 1947 | In 1947, on its independence from the United Kingdom, India granted equal voting rights to all men and women. | |

| 1937 (for Europeans only) 1945 (for all citizens, granted upon independence) |

||

| 1963 | In 1945, during the one-year rule of the Azerbaijani Democratic Party, Iranian Azerbaijani women were allowed to vote and be elected. | |

| 1980 | ||

| 1918 (partial) 1922 (full) |

From 1918, with the rest of the United Kingdom, women could vote at 30 with property qualifications or in university constituencies, while men could vote at 21 with no qualification. From separation in 1922, the Irish Free State gave equal voting rights to men and women.[54] | |

| 1881 | ||

| 1948 | Women's suffrage was granted with the declaration of independence. But prior to that in the Jewish settlement in Palestine, suffrage was granted in 1920. | |

| 1925 (partial), 1945 (full) | Local elections in 1925. Full suffrage in 1945. | |

| 1944 | ||

| 1946 | 1946 Japanese general election | |

| 1919[55] | Restrictions on franchise applied to men and women until after Liberation in 1945. | |

| 1974 | ||

| 1924 | ||

| 1963 | ||

| 1967 | ||

| 1946[56] | ||

| 1948 | ||

| 1985[57] – women's suffrage later removed in 1999, re-granted in 2005 | All voters must have been citizens of Kuwait for at least 20 years.[58] | |

| 1918 | ||

| 1958 | ||

| 1917 | ||

| 1952[59] | In 1952, after a 30 year long battle for suffrage, the bill allowing Lebanese women to vote passed.[60] In 1957 a requirement for women (but not men) to have elementary education before voting was dropped, as was voting being compulsory for men.[61] | |

| 1965 | ||

| 1946 | ||

| 1963 (1951 local) | [62] | |

| 1984 | ||

| 1918 | ||

| 1919 | Women gained the vote on 15 May 1919 through amendment of Article 52 of Luxembourg's constitution. | |

| 1959 | ||

| 1961 | ||

| 1955 | First general election for the Federal Legislative Council, two years before independence in 1957 | |

| 1932 | ||

| 1956 | ||

| 1947 | ||

| 1979 | ||

| 1961 | ||

| 1956 | ||

| 1953 | ||

| 1979 | ||

| 1929/1940 | As part of the Kingdom of Romania, women who met certain qualifications were allowed to vote in local elections, starting in 1929. After the Constitution of 1938, voting rights were extended to women for general elections by the Electoral Law 1939.[63] In 1940, after the formation of the Moldavian SSR, equal voting rights were granted to men and women. | |

| 1962 | ||

| 1924 | ||

| 1963 | ||

| 1975 | ||

| 1989 (upon its independence) | At independence from South Africa. | |

| 1968 | ||

| 1951 | ||

| 1917 | Women have been allowed to vote since 1919. Since 1917 women have been allowed to be voted into office. | |

| 1949 | ||

| 1893 | ||

| 1955 | ||

| 1948 | ||

| 1958 | ||

| 1913 | ||

| 1994 | ||

| 1947 | In 1947, on its creation at the partition of India, Pakistan granted full voting rights to men and women. | |

| 1979 | ||

| 1996 | Women first voted in local elections in the West Bank in 1976. Women (and men) first elected a Palestinian parliament in 1996. However, the last general election was in 2006; there was supposed to be another in 2014 but elections have been delayed indefinitely. | |

| 1941/1946 | Limited women's suffrage from 1941 (conditioned by level of education) equal women's suffrage from 1946.[46] | |

| 1964 | ||

| 1961 | ||

| 1955 | ||

| 1937 | ||

| 1838 | ||

| 1918 | ||

| 1911/1931/1976 | With restrictions in 1911, later made illegal again until 1931 when it was reinstated with restrictions,[64] restrictions other than age requirements lifted in 1976.[64][65] | |

| 1929/1935 | Limited suffrage was passed for women, restricted to those who were literate. In 1935 the legislature approved suffrage for all women. | |

| 1997 | While required by the constitution, general elections have been repeatedly delayed.[66] Only municipal elections have been held thus far. | |

| 1929/1939/1946 | Starting in 1929, women who met certain qualifications were allowed to vote in local elections. After the Constitution from 1938, the voting rights were extended to women for general elections by the Electoral Law 1939. Women could vote on equal terms with men, but both men and women had restrictions, and in practice the restrictions affected women more than men. In 1946, full equal voting rights were granted to men and women.[63] | |

| 1917 | On July 20, 1917, under the Provisional Government. | |

| 1961 | ||

| 2015 | In December 2015, women were first allowed to vote and run for office. Suffrage for both men and women is limited to municipal elections. | |

| 1990 | ||

| 1959 | ||

| 1975 | ||

| 1945 | ||

| 1948 | ||

| 1961 | In the 1790s, while Sierra Leone was still a colony, women voted in the elections.[67] | |

| 1947 | ||

| 1974 | ||

| 1956 | ||

| 1930 (European and Asian women) 1994 (all women) |

Women of other races were enfranchised in 1994, at the same time as men of all races. | |

| 1924[68][69][70] /1 October 1931[68][71][72] 1977[71] | Women briefly held the right to vote from 1924 to 1926, but an absence of elections mean they never had the opportunity to go to the polls until 1933, after earning the right to vote in the 1931 Constitution passed after the elections.[68][71][72] The government fell after only two elections where women could vote, and no one would vote again until after the death of Francisco Franco.[71] | |

| 1931 | ||

| 1964 | ||

| 1948 | ||

| 1968 | ||

| 1919 | ||

| 1971 at federal level, 1959–1991 at local canton level | Women obtained the right to vote in national elections in 1971.[73] Women obtained the right to vote at local canton level between 1959 (Vaud and Neuchâtel in that year) and 1972, except for 1990 in Appenzell.[74] See also Women's suffrage in Switzerland. | |

| 1949 | ||

| 1848 | ||

| 1947 | In 1945, the island of Taiwan was returned from Japan to China. In 1947, women won the suffrage under the Constitution of the Republic of China. In 1949, the Government of the Republic of China (ROC) lost mainland China and moved to Taiwan. | |

| 1924 | ||

| 1959 | ||

| 1932 | ||

| 1976 | ||

| 1945 | ||

| 1960 | ||

| 1925 | Suffrage was granted for the first time in 1925 to either sex, to men over the age of 21 and women over the age of 30, as in Great Britain (the "Mother Country", as Trinidad and Tobago was still a colony at the time)[75] In 1945 full suffrage was granted to women.[76] | |

| 1957 | ||

| 1930 (for local elections), 1934 (for national elections) | ||

| 1924 | ||

| 1967 | ||

| 1962 | ||

| 1919 | ||

| 2006 | Limited suffrage for both men and women.[77][78] | |

| 1918 (partial) 1928 (full) |

From 1918–1928, women could vote at 30 with property qualifications or as graduates of UK universities, while men could vote at 21 with no qualification. From 1928 women had equal suffrage with men. | |

| 1920 | Before the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920, individual states had passed legislation that allowed women to vote in different types of elections; some only allowed women to vote in school or municipal elections, some required that women owned property if they wanted to vote, and some territories extended full suffrage to women, only to take it away once they became states.[79] Although legally entitled to vote, black women were effectively denied voting rights in numerous Southern states until 1965. | |

| 1936 | Beginning in 1936 women could vote; however, this vote, as with men, was limited to those who could prove they had an income of $300 per year or more. | |

| 1917/1927 | Uruguay was the first country in all of the Americas – and one of the first in the world – to grant women fully equal civil rights and universal suffrage (in its Constitution of 1917), though this suffrage was first exercised in 1927, in the plebiscite of Cerro Chato.[80] | |

| 1938 | ||

| 1975 | ||

| No voting | The Pope, elected by the all-male College of Cardinals through a secret ballot, is the leader of the Catholic Church, and exercises ex officio supreme legislative, executive, and judicial power over the State of the Vatican City.[81] | |

| 1946 | ||

| 1946 | ||

| 1970 | ||

| 1967 | ||

| 1962 (then Northern Rhodesia) | Women's suffrage granted in Northern Rhodesia in 1962.[82] | |

| 1919 | ||

| 1945 |

By continent

Africa

Egypt

The struggle for women's suffrage in Egypt first sparked from the nationalist 1919 Revolution in which women of all classes took to the streets in protest against the British occupation. The struggle was led by several Egyptian women's rights pioneers in the first half of the 20th century through protest, journalism, and lobbying. President Gamal Abdel-Nasser supported women's suffrage in 1956 after they were denied the vote under the British occupation.[83]

Sierra Leone

One of the first occasions when women were able to vote was in the elections of the Nova Scotian settlers at Freetown. In the 1792 elections, all heads of household could vote and one-third were ethnic African women.[84] Women won the right to vote in Sierra Leone in 1930.[85]

South Africa

The franchise was extended to white women 21 years or older by the Women's Enfranchisement Act, 1930. The first general election at which women could vote was the 1933 election. At that election Leila Reitz (wife of Deneys Reitz) was elected as the first female MP, representing Parktown for the South African Party. The limited voting rights available to non-white men in the Cape Province and Natal (Transvaal and the Orange Free State practically denied all non-whites the right to vote, and had also done so to white foreign nationals when independent in the 1800s) were not extended to women, and were themselves progressively eliminated between 1936 and 1968.

The right to vote for the Transkei Legislative Assembly, established in 1963 for the Transkei bantustan, was granted to all adult citizens of the Transkei, including women. Similar provision was made for the Legislative Assemblies created for other bantustans. All adult coloured citizens were eligible to vote for the Coloured Persons Representative Council, which was established in 1968 with limited legislative powers; the council was however abolished in 1980. Similarly, all adult Indian citizens were eligible to vote for the South African Indian Council in 1981. In 1984 the Tricameral Parliament was established, and the right to vote for the House of Representatives and House of Delegates was granted to all adult Coloured and Indian citizens, respectively.

In 1994 the bantustans and the Tricameral Parliament were abolished and the right to vote for the National Assembly was granted to all adult citizens.

Southern Rhodesia

Southern Rhodesian white women won the vote in 1919 and Ethel Tawse Jollie (1875–1950) was elected to the Southern Rhodesia legislature 1920–1928, the first woman to sit in any national Commonwealth Parliament outside Westminster. The influx of women settlers from Britain proved a decisive factor in the 1922 referendum that rejected annexation by a South Africa increasingly under the sway of traditionalist Afrikaner Nationalists in favor of Rhodesian Home Rule or "responsible government".[86] Black Rhodesian males qualified for the vote in 1923 (based only upon property, assets, income, and literacy). It is unclear when the first black woman qualified for the vote.

Asia

Afghanistan

Women have been able to vote in Afghanistan since 1965 (except during Taliban rule, 1996–2001, when no elections were held).[87] As of 2009, women have been casting fewer ballots in part due to being unaware of their voting rights.[88] In the 2014 election, Afghanistan's elected president pledged to bring women equal rights.[89]

Bangladesh

Bangladesh was (mostly) the province of Bengal in India until 1947, then it became part of Pakistan. It became an independent nation in 1971. Women have had equal suffrage since 1947, and they have reserved seats in parliament. Bangladesh is notable in that since 1991, two women, namely Sheikh Hasina and Begum Khaleda Zia, have served terms as the country's Prime Minister continuously. Women have traditionally played a minimal role in politics beyond the anomaly of the two leaders; few used to run against men; few have been ministers. Recently, however, women have become more active in politics, with several prominent ministerial posts given to women and women participating in national, district and municipal elections against men and winning on several occasions. Choudhury and Hasanuzzaman argue that the strong patriarchal traditions of Bangladesh explain why women are so reluctant to stand up in politics.[90]

India

Women in India were allowed to vote right from the first general elections after the independence of India in 1947 unlike during the British rule who resisted allowing women to vote.[91] The Women's Indian Association (WIA) was founded in 1917. It sought votes for women and the right to hold legislative office on the same basis as men. These positions were endorsed by the main political groupings, the Indian National Congress.[92] British and Indian feminists combined in 1918 to publish a magazine Stri Dharma that featured international news from a feminist perspective.[93] In 1919 in the Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms, the British set up provincial legislatures which had the power to grant women's suffrage. Madras in 1921 granted votes to wealthy and educated women, under the same terms that applied to men. The other provinces followed, but not the princely states (which did not have votes for men either, being monarchies).[92] In Bengal province, the provincial assembly rejected it in 1921 but Southard shows an intense campaign produced victory in 1921. Success in Bengal depended on middle class Indian women, who emerged from a fast-growing urban elite. The women leaders in Bengal linked their crusade to a moderate nationalist agenda, by showing how they could participate more fully in nation-building by having voting power. They carefully avoided attacking traditional gender roles by arguing that traditions could coexist with political modernization.[94]

Whereas wealthy and educated women in Madras were granted voting right in 1921, in Punjab the Sikhs granted women equal voting rights in 1925 irrespective of their educational qualifications or being wealthy or poor. This happened when the Gurdwara Act of 1925 was approved. The original draft of the Gurdwara Act sent by the British to the Sharomani Gurdwara Prabhandak Committee (SGPC) did not include Sikh women, but the Sikhs inserted the clause without the women having to ask for it. Equality of women with men is enshrined in the Guru Granth Sahib, the sacred scripture of the Sikh faith.

In the Government of India Act 1935 the British Raj set up a system of separate electorates and separate seats for women. Most women's leaders opposed segregated electorates and demanded adult franchise. In 1931 the Congress promised universal adult franchise when it came to power. It enacted equal voting rights for both men and women in 1947.[95]

Indonesia

Indonesia granted women voting rights for municipal councils in 1905. Only men who could read and write could vote, which excluded many non-European males. At the time, the literacy rate for males was 11% and for females 2%. The main group that pressed for women's suffrage in Indonesia was the Dutch Vereeninging voor Vrouwenkiesrecht (VVV-Women's Suffrage Association), founded in the Netherlands in 1894. VVV tried to attract Indonesian members, but had very limited success because the leaders of the organization had little skill in relating to even the educated class of Indonesians. When they eventually did connect somewhat with women, they failed to sympathize with them and ended up alienating many well-educated Indonesians. In 1918 the first national representative body, the Volksraad, was formed which still excluded women from voting. In 1935, the colonial administration used its power of nomination to appoint a European woman to the Volksraad. In 1938, women gained the right to be elected to urban representative institutions, which led to some Indonesian and European women entering municipal councils. Eventually, only European women and municipal councils could vote, excluding all other women and local councils. In September 1941, the Volksraad extended the vote to women of all races. Finally, in November 1941, the right to vote for municipal councils was granted to all women on a similar basis to men (subject to property and educational qualifications).[96]

Iran

A referendum in January 1963 overwhelmingly approved by voters gave women the right to vote, a right previously denied to them under the Iranian Constitution of 1906 pursuant to Chapter 2, Article 3.[87]

Israel

Women have had full suffrage since the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948.

The first (and as of 2020, the only) woman to be elected Prime Minister of Israel was Golda Meir in 1969.

Japan

Although women were allowed to vote in some prefectures in 1880, women's suffrage was enacted at a national level in 1945.[97]

Korea

South Korean women were granted the vote in 1948.[98]

Kuwait

When voting was first introduced in Kuwait in 1985, Kuwaiti women had the right to vote.[57] The right was later removed. In May 2005, the Kuwaiti parliament re-granted female suffrage.[99]

Lebanon

Pakistan

Pakistan was part of British Raj until 1947, when it became independent. Women received full suffrage in 1947. Muslim women leaders from all classes actively supported the Pakistan movement in the mid-1940s. Their movement was led by wives and other relatives of leading politicians. Women were sometimes organized into large-scale public demonstrations. In November 1988, Benazir Bhutto became the first Muslim woman to be elected as Prime Minister of a Muslim country.[100]

Philippines

The Philippines was one of the first countries in Asia to grant women the right to vote.[101] Suffrage for Filipinas was achieved following an all-female, special plebiscite held on 30 April 1937. 447,725 – some ninety percent – voted in favour of women's suffrage against 44,307 who voted no. In compliance with the 1935 Constitution, the National Assembly passed a law which extended the right of suffrage to women, which remains to this day.[102][101]

Saudi Arabia

In late September 2011, King Abdullah bin Abdulaziz al-Saud declared that women would be able to vote and run for office starting in 2015. That applies to the municipal councils, which are the kingdom's only semi-elected bodies. Half of the seats on municipal councils are elective, and the councils have few powers.[103] The council elections have been held since 2005 (the first time they were held before that was the 1960s).[104][105] Saudi women did first vote and first run for office in December 2015, for those councils.[106] Salma bint Hizab al-Oteibi became the first elected female politician in Saudi Arabia in December 2015, when she won a seat on the council in Madrakah in Mecca province.[107] In all, the December 2015 election in Saudi Arabia resulted in twenty women being elected to municipal councils.[108]

The king declared in 2011 that women would be eligible to be appointed to the Shura Council, an unelected body that issues advisory opinions on national policy.[109] '"This is great news," said Saudi writer and women's rights activist Wajeha al-Huwaider. "Women's voices will finally be heard. Now it is time to remove other barriers like not allowing women to drive cars and not being able to function, to live a normal life without male guardians."' Robert Lacey, author of two books about the kingdom, said, "This is the first positive, progressive speech out of the government since the Arab Spring.... First the warnings, then the payments, now the beginnings of solid reform." The king made the announcement in a five-minute speech to the Shura Council.[104] In January 2013, King Abdullah issued two royal decrees, granting women thirty seats on the council, and stating that women must always hold at least a fifth of the seats on the council.[110] According to the decrees, the female council members must be "committed to Islamic Shariah disciplines without any violations" and be "restrained by the religious veil."[110] The decrees also said that the female council members would be entering the council building from special gates, sit in seats reserved for women and pray in special worshipping places.[110] Earlier, officials said that a screen would separate genders and an internal communications network would allow men and women to communicate.[110] Women first joined the council in 2013, occupying thirty seats.[111][112] There are two Saudi royal women among these thirty female members of the assembly, Sara bint Faisal Al Saud and Moudi bint Khalid Al Saud.[113] Furthermore, in 2013 three women were named as deputy chairpersons of three committees: Thurayya Obeid was named deputy chairwoman of the human rights and petitions committee, Zainab Abu Talib, deputy chairwoman of the information and cultural committee, and Lubna Al Ansari, deputy chairwoman of the health affairs and environment committee.[111]

Sri Lanka

In 1931 Sri Lanka (at that time Ceylon) became one of the first Asian countries to allow voting rights to women over the age of 21 without any restrictions. Since then, women have enjoyed a significant presence in the Sri Lankan political arena. The zenith of this favourable condition to women has been the 1960 July General Elections, in which Ceylon elected the world's first woman Prime Minister, Sirimavo Bandaranaike. She is the world's first democratically elected female head of government. Her daughter, Chandrika Kumaratunga also became the Prime Minister later in 1994, and the same year she was elected as the Executive President of Sri Lanka, making her the fourth woman in the world to be elected president, and the first female executive president.

Europe

In Europe, the last countries to enact women's suffrage were Switzerland and Liechtenstein. In Switzerland, women gained the right to vote in federal elections in 1971;[114] but in the canton of Appenzell Innerrhoden women obtained the right to vote on local issues only in 1991, when the canton was forced to do so by the Federal Supreme Court of Switzerland.[115] In Liechtenstein, women were given the right to vote by the women's suffrage referendum of 1984. Three prior referendums held in 1968, 1971 and 1973 had failed to secure women's right to vote.[116]

Austria

It was only after the breakdown of the Habsburg Monarchy, that Austria would grant the general, equal, direct and secret right to vote to all citizens, regardless of sex, through the change of the electoral code in December 1918.[43] The first elections in which women participated were the February 1919 Constituent Assembly elections.[117]

Azerbaijan

Universal voting rights were recognized in Azerbaijan in 1918 by the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic.[45]

Belgium

A revision of the constitution in October 1921 (it changed art. 47 of the Constitution of Belgium of 1831) introduced the general right to vote according to the "one man, one vote" principle. Art. 47 allowed widows of World War I to vote at the national level as well.[118] The introduction of women's suffrage was already put onto the agenda at the time, by means of including an article in the constitution that allowed approval of women's suffrage by special law (meaning it needed a 2/3 majority to pass).[119] This happened in March 1948. In Belgium, voting is compulsory.

Bulgaria

Bulgaria was liberated from Ottoman rule in 1878. Although the first adopted constitution, the Tarnovo Constitution (1879), gave women equal election rights, in fact women were not allowed to vote and to be elected. The Bulgarian Women's Union was an umbrella organization of the 27 local women's organisations that had been established in Bulgaria since 1878. It was founded as a reply to the limitations of women's education and access to university studies in the 1890s, with the goal to further women's intellectual development and participation, arranged national congresses and used Zhenski glas as its organ. However, they have limited success, and women were allowed to vote and to be elected only after when Communist rule was established.

Croatia

Czechia

In the former Bohemia, taxpaying women and women in "learned profession[s]" were allowed to vote by proxy and made eligible to the legislative body in 1864.[120] The first Czech female MP was elected to the Diet of Bohemia in 1912. The Declaration of Independence of the Czechoslovak Nation from 18 October 1918 declared that “our democracy shall rest on universal suffrage. Women shall be placed on equal footing with men, politically, socially, and culturally,” and women were appointed to the Revolutionary National Assembly (parliament) on 13 November 1918. On 15 June 1919, women voted in local elections for the first time. Women were guaranteed equal voting rights by the constitution of the Czechoslovak Republic in February 1920 and were able to vote for the parliament for the first time in April 1920.[121]

Denmark

%2C.jpg)

In Denmark, the Danish Women's Society (DK) debated, and informally supported, women's suffrage from 1884, but it did not support it publicly until in 1887, when it supported the suggestion of the parliamentarian Fredrik Bajer to grant women municipal suffrage.[122] In 1886, in response to the perceived overcautious attitude of DK in the question of women suffrage, Matilde Bajer founded the Kvindelig Fremskridtsforening (or KF, 1886–1904) to deal exclusively with the right to suffrage, both in municipal and national elections, and it 1887, the Danish women publicly demanded the right for women's suffrage for the first time through the KF. However, as the KF was very much involved with worker's rights and pacifist activity, the question of women's suffrage was in fact not given full attention, which led to the establishment of the strictly women's suffrage movement Kvindevalgretsforeningen (1889–1897).[122] In 1890, the KF and the Kvindevalgretsforeningen united with five women's trade worker's unions to found the De samlede Kvindeforeninger, and through this form, an active women's suffrage campaign was arranged through agitation and demonstration. However, after having been met by compact resistance, the Danish suffrage movement almost discontinued with the dissolution of the De samlede Kvindeforeninger in 1893.[122]

In 1898, an umbrella organization, the Danske Kvindeforeningers Valgretsforbund or DKV was founded and became a part of the International Woman Suffrage Alliance (IWSA).[122] In 1907, the Landsforbundet for Kvinders Valgret (LKV) was founded by Elna Munch, Johanne Rambusch and Marie Hjelmer in reply to what they considered to be the much too careful attitude of the Danish Women's Society. The LKV originated from a local suffrage association in Copenhagen, and like its rival DKV, it successfully organized other such local associations nationally.[122]

Women won the right to vote in municipal elections on April 20, 1908. However it was not until June 5, 1915 that they were allowed to vote in Rigsdag elections.[123]

Estonia

Estonia gained its independence in 1918 with the Estonian War of Independence. However, the first official elections were held in 1917. These were the elections of temporary council (i.e. Maapäev), which ruled Estonia from 1917–1919. Since then, women have had the right to vote.

The parliament elections were held in 1920. After the elections, two women got into the parliament – history teacher Emma Asson and journalist Alma Ostra-Oinas. Estonian parliament is called Riigikogu and during the First Republic of Estonia it used to have 100 seats.

Finland

.jpg)

The area that in 1809 became Finland was a group of integral provinces of the Kingdom of Sweden for over 600 years. Thus, women in Finland were allowed to vote during the Swedish Age of Liberty (1718–1772), during which conditional suffrage was granted to tax-paying female members of guilds.[124] However, this right was controversial. In Vaasa, there was opposition against women participating in the town hall discussing political issues, as this was not seen as their right place, and women's suffrage appears to have been opposed in practice in some parts of the realm: when Anna Elisabeth Baer and two other women petitioned to vote in Turku in 1771, they were not allowed to do so by town officials.[125]

The predecessor state of modern Finland, the Grand Duchy of Finland, was part of the Russian Empire from 1809 to 1917 and enjoyed a high degree of autonomy. In 1863, taxpaying women were granted municipal suffrage in the country side, and in 1872, the same reform was given to the cities.[120] In 1906, it became the first province in the world to implement racially-equal women’s suffrage, unlike Australia in 1902. It also elected the world's first female members of parliament the following year.[4][5] Miina Sillanpää became Finland’s first female government minister in 1926.[126]

France

The 21 April 1944 ordinance of the French Committee of National Liberation, confirmed in October 1944 by the French provisional government, extended the suffrage to French women.[127][128] The first elections with female participation were the municipal elections of 29 April 1945 and the parliamentary elections of 21 October 1945. "Indigenous Muslim" women in French Algeria also known as Colonial Algeria, had to wait until a 3 July 1958 decree.[129][130] Although several countries had started extending suffrage to women from the end of the 19th century, France was one of the last countries to do so in Europe. In fact, the Napoleonic Code declares the legal and political incapacity of women, which blocked attempts to give women political rights.[131] First feminist claims started emerging during the French Revolution in 1789. Condorcet expressed his support for women's right to vote in an article published in Journal de la Société de 1789, but his project failed.[132] After World War I, French women continued demanding political rights, and despite the Chamber of Deputies being in favor, the Senate continuously refused to analyze the law proposal.[132] Surprisingly, the political left, who were generally supportive of women's emancipation, repeatedly opposed the right to vote for women because they would support conservative positions.[131] It was only after World War II that women were granted political rights.

Georgia

Upon its declaration of independence on 26 May 1918, in the aftermath of the Russian Revolution, the Democratic Republic of Georgia extended suffrage to its female citizens. The women of Georgia first exercised their right to vote in the 1919 legislative election.[133]

Germany

Women were granted the right to vote and be elected from the 12th November 1918. The Weimar Constitution established a new "Germany" after the kids of World War 1 and extended the right to vote to all citizens above the age of 20. ( With some exceptions)[87]

Greece

Greece had had universal suffrage since its independence in 1832, but it excluded women. The first proposal to give Greek women the right to vote was made on 19 May 1922 by a member of parliament, supported by then Prime Minister Dimitrios Gounaris, during a constitutional convention.[134] The proposal garnered a narrow majority of those present when it was first proposed, but failed to get the broad 80% support needed to add it to the constitution.[134] In 1925 consultations began again, and a law was passed allowing women the right to vote in local elections, provided they were 30 years of age and had attended at least primary education.[134] The law remained unenforced, until feminist movements within the civil service lobbied the government to enforce it in December 1927 and March 1929.[134] Women were allowed to vote on a local level for the first time in the Thessaloniki local elections, on 14 December 1930, where 240 women exercised their right to do so.[134] Women's turnout remained low, at only around 15,000 in the national local elections of 1934, despite women being a narrow majority of the population of 6.8 million.[134] Women could not stand for election, despite a proposal made by Interior minister Ioannis Rallis, which was contested in the courts; the courts ruled that the law only gave women "a limited franchise" and struck down any lists where women were listed as candidates for local councils.[134] Misogyny was rampant in that era; Emmanuel Rhoides is quoted as having said that "two professions are fit for women: housewife and prostitute".[135]

On a national level women over 18 voted for the first time in April 1944 for the National Council, a legislative body set up by the National Liberation Front resistance movement. Ultimately, women won the legal right to vote and run for office on 28 May 1952. Eleni Skoura, again from Thessaloniki, became the first woman elected to the Hellenic Parliament in 1953, with the conservative Greek Rally, when she won a by-election against another female opponent.[136] Women were finally able to participate in the 1956 election, with two more women becoming Members of Parliament; Lina Tsaldari, wife of former Prime Minister Panagis Tsaldaris, won the most votes of any candidate in the country and became the first female minister in Greece under the conservative National Radical Union government of Konstantinos Karamanlis.[136]

No woman has been elected Prime Minister of Greece, but Vassiliki Thanou-Christophilou served as the country's first female Prime Minister, heading a caretaker government, between 27 August and 21 September 2015. The first woman to lead a major political party was Aleka Papariga, who served as General Secretary of the Communist Party of Greece from 1991 to 2013.

Hungary

In Hungary, although it was already planned in 1818, the first occasion when women could vote was the elections held in January 1920.

Ireland

From 1918, with the rest of the United Kingdom, women in Ireland could vote at age 30 with property qualifications or in university constituencies, while men could vote at age 21 with no qualification. From separation in 1922, the Irish Free State gave equal voting rights to men and women. [“All citizens of the Irish Free State (Saorstát Eireann) without distinction of sex, who have reached the age of twenty-one years and who comply with the provisions of the prevailing electoral laws, shall have the right to vote for members of Dáil Eireann, and to take part in the Referendum and Initiative.”][137] Promises of equal rights from the Proclamation were embraced in the Constitution in 1922, the year Irish women achieved full voting rights. However over the next ten years laws were introduced that eliminated women's rights from serving on juries, working after marriage, and working in industry. The 1937 Constitution and Taoiseach Éamon de Valera’s conservative leadership further stripped women of their previously granted rights.[138] As well, though the 1937 Constitution guarantees women the right to vote and to nationality and citizenship on an equal basis with men, it also contains a provision, Article 41.2, which states:

1° [...] the State recognises that by her life within the home, woman gives to the State a support without which the common good cannot be achieved. 2° The State shall, therefore, endeavour to ensure that mothers shall not be obliged by economic necessity to engage in labour to the neglect of their duties in the home.

Isle of Man

In 1881, The Isle of Man (in the British Isles but not part of the United Kingdom) passed a law giving the vote to single and widowed women who passed a property qualification. This was to vote in elections for the House of Keys, in the Island's parliament, Tynwald. This was extended to universal suffrage for men and women in 1919.[139]

Italy

In Italy, women's suffrage was not introduced following World War I, but upheld by Socialist and Fascist activists and partly introduced by Benito Mussolini's government in 1925.[140] In April 1945, the provisional government decreed the enfranchisement of women allowing for the immediate appointment of women to public office, of which the first was Elena Fischli Dreher.[141] In the 1946 election, all Italians simultaneously voted for the Constituent Assembly and for a referendum about keeping Italy a monarchy or creating a republic instead. Elections were not held in the Julian March and South Tyrol because they were under Allied occupation.

The new version of article 51 Constitution recognizes equal opportunities in electoral lists.[142]

Liechtenstein

In Liechtenstein, women's suffrage was granted via referendum in 1984.[143]

Luxemburg

In Luxemburg, Marguerite Thomas-Clement spoke in favour of women suffrage in public debate through articles in the press in 1917-19; however, there was never any organized women suffrage movement in Luxemburg, as women suffrage was included without debate in the new democratic constitution of 1919.[144]

Netherlands

Women were granted the right to vote in the Netherlands on August 9, 1919.[87] In 1917, a constitutional reform already allowed women to be electable. However, even though women's right to vote was approved in 1919, this only took effect from January 1, 1920.

The women's suffrage movement in the Netherlands was led by three women: Aletta Jacobs, Wilhelmina Drucker and Annette Versluys-Poelman. In 1889, Wilhelmina Drucker founded a women's movement called Vrije Vrouwen Vereeniging (Free Women’s Union) and it was from this movement that the campaign for women's suffrage in the Netherlands emerged. This movement got a lot of support from other countries, especially from the women's suffrage movement in England. In 1906 the movement wrote an open letter to the Queen pleading for women's suffrage. When this letter was rejected, in spite of popular support, the movement organised several demonstrations and protests in favor of women's suffrage. This movement was of great significance for women's suffrage in the Netherlands.[145]

Norway

Liberal politician Gina Krog was the leading campaigner for women's suffrage in Norway from the 1880s. She founded the Norwegian Association for Women's Rights and the National Association for Women's Suffrage to promote this cause. Members of these organisations were politically well-connected and well organised and in a few years gradually succeeded in obtaining equal rights for women. Middle class women won the right to vote in municipal elections in 1901 and parliamentary elections in 1907. Universal suffrage for women in municipal elections was introduced in 1910, and in 1913 a motion on universal suffrage for women was adopted unanimously by the Norwegian parliament (Stortinget).[146] Norway thus became the first independent country to introduce women's suffrage.[147]

Poland

Regaining independence in 1918 following the 123-year period of partition and foreign rule,[148] Poland immediately granted women the right to vote and be elected as of 28 November 1918.[87]

The first women elected to the Sejm in 1919 were: Gabriela Balicka, Jadwiga Dziubińska, Irena Kosmowska, Maria Moczydłowska, Zofia Moraczewska, Anna Piasecka, Zofia Sokolnicka, and Franciszka Wilczkowiakowa.[149][150]

Portugal

Carolina Beatriz Ângelo was the first Portuguese woman to vote, in the Constituent National Assembly election of 1911,[151] taking advantage of a loophole in the country's electoral law.

In 1931 during the Estado Novo regime, women were allowed to vote for the first time, but only if they had a high school or university degree, while men had only to be able to read and write. In 1946 a new electoral law enlarged the possibility of female vote, but still with some differences regarding men. A law from 1968 claimed to establish "equality of political rights for men and women", but a few electoral rights were reserved for men. After the Carnation Revolution, women were granted full and equal electoral rights in 1976.[64][65]

Romania

The timeline of granting women's suffrage in Romania was gradual and complex, due to the turbulent historical period when it happened. The concept of universal suffrage for all men was introduced in 1918,[152] and reinforced by the 1923 Constitution of Romania. Although this constitution opened the way for the possibility of women's suffrage too (Article 6),[153] this did not materialize: the Electoral Law of 1926 did not grant women the right to vote, maintaining all male suffrage.[154] Starting in 1929, women who met certain qualifications were allowed to vote in local elections.[154] After the Constitution from 1938 (elaborated under Carol II of Romania who sought to implement an authoritarian regime) the voting rights were extended to women for national elections by the Electoral Law 1939,[155] but both women and men had restrictions, and in practice these restrictions affected women more than men (the new restrictions on men also meant that men lost their previous universal suffrage). Although women could vote, they could be elected only to the Senate and not to the Chamber of Deputies (Article 4 (c)).[155] (the Senate was later abolished in 1940). Due to the historical context of the time, which included the dictatorship of Ion Antonescu, there were no elections in Romania between 1940–1946. In 1946, Law no. 560 gave full equal rights to men and women to vote and to be elected in the Chamber of Deputies; and women voted in the 1946 Romanian general election.[156] The Constitution of 1948 gave women and men equal civil and political rights (Article 18).[157] Until the collapse of communism in 1989, all the candidates were chosen by the Romanian Communist Party, and civil rights were merely symbolic under this authoritarian regime.[158]

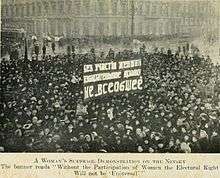

Russia

Despite initial apprehension against enfranchising women for the right to vote for the upcoming Constituent Assembly election, the League for Women's Equality and other suffragists rallied throughout the year of 1917 for the right to vote. After much pressure (including a 40,000-strong march on the Tauride Palace), on July 20, 1917 the Provisional Government enfranchised women with the right to vote.[159]

San Marino

San Marino introduced women's suffrage in 1959,[64] following the 1957 constitutional crisis known as Fatti di Rovereta. It was however only in 1973 that women obtained the right to stand for election.[64]

Spain

During the Miguel Primo de Rivera[160] regime (1923–1930) only women who were considered heads of household were allowed to vote in local elections, but there were none at that time. Women's suffrage was officially adopted in 1931 despite the opposition of Margarita Nelken and Victoria Kent, two female MPs (both members of the Republican Radical-Socialist Party), who argued that women in Spain at that moment lacked social and political education enough to vote responsibly because they would be unduly influenced by Catholic priests. During the Franco regime in the "organic democracy" type of elections called "referendums" (Franco's regime was dictatorial) women over 21 were allowed to vote without distinction.[161] From 1976, during the Spanish transition to democracy women fully exercised the right to vote and be elected to office.

Sweden

During the Age of Liberty (1718–1772), Sweden had conditional women's suffrage.[13] Until the reform of 1865, the local elections consisted of mayoral elections in the cities, and elections of parish vicars in the countryside parishes. The Sockenstämma was the local parish council who handled local affairs, in which the parish vicar presided and the local peasantry assembled and voted, an informally regulated process in which women are reported to have participated already in the 17th century.[162] The national elections consisted of the election of the representations to the Riksdag of the Estates.

Suffrage was gender neutral and therefore applied to women as well as men if they filled the qualifications of a voting citizen.[13] These qualifications were changed during the course of the 18th-century, as well as the local interpretation of the credentials, affecting the number of qualified voters: the qualifications also differed between cities and countryside, as well as local or national elections.[13]

Initially, the right to vote in local city elections (mayoral elections) was granted to every burgher, which was defined as a taxpaying citizen with a guild membership.[13] Women as well as men were members of guilds, which resulted in women's suffrage for a limited number of women.[13] In 1734, suffrage in both national and local elections, in cities as well as countryside, was granted to every property owning taxpaying citizen of legal majority.[13] This extended suffrage to all taxpaying property owning women whether guild members or not, but excluded married women and the majority of unmarried women, as married women were defined as legal minors, and unmarried women were minors unless they applied for legal majority by royal dispensation, while widowed and divorced women were of legal majority.[13] The 1734 reform increased the participation of women in elections from 55 to 71 percent.[13]

Between 1726 and 1742, women voted in 17 of 31 examined mayoral elections.[13] Reportedly, some women voters in mayoral elections preferred to appoint a male to vote for them by proxy in the city hall because they found it embarrassing to do so in person, which was cited as a reason to abolish women's suffrage by its opponents.[13] The custom to appoint to vote by proxy was however used also by males, and it was in fact common for men, who were absent or ill during elections, to appoint their wives to vote for them.[13] In Vaasa in Finland (then a Swedish province), there was opposition against women participating in the town hall discussing political issues as this was not seen as their right place, and women's suffrage appears to have been opposed in practice in some parts of the realm: when Anna Elisabeth Baer and two other women petitioned to vote in Åbo in 1771, they were not allowed to do so by town officials.[125]

In 1758, women were excluded from mayoral elections by a new regulation by which they could no longer be defined as burghers, but women's suffrage was kept in the national elections as well as the countryside parish elections.[13] Women participated in all of the eleven national elections held up until 1757.[13] In 1772, women's suffrage in national elections was abolished by demand from the burgher estate. Women's suffrage was first abolished for taxpaying unmarried women of legal majority, and then for widows.[13] However, the local interpretation of the prohibition of women's suffrage varied, and some cities continued to allow women to vote: in Kalmar, Växjö, Västervik, Simrishamn, Ystad, Åmål, Karlstad, Bergslagen, Dalarna and Norrland, women were allowed to continue to vote despite the 1772 ban, while in Lund, Uppsala, Skara, Åbo, Gothenburg and Marstrand, women were strictly barred from the vote after 1772.[13]

While women's suffrage was banned in the mayoral elections in 1758 and in the national elections in 1772, no such bar was ever introduced in the local elections in the countryside, where women therefore continued to vote in the local parish elections of vicars.[13] In a series of reforms in 1813–1817, unmarried women of legal majority, "Unmarried maiden, who has been declared of legal majority", were given the right to vote in the sockestämma (local parish council, the predecessor of the communal and city councils), and the kyrkoråd (local church councils).[163]

In 1823, a suggestion was raised by the mayor of Strängnäs to reintroduce women's suffrage for taxpaying women of legal majority (unmarried, divorced and widowed women) in the mayoral elections, and this right was reintroduced in 1858.[162]

In 1862, tax-paying women of legal majority (unmarried, divorced and widowed women) were again allowed to vote in municipal elections, making Sweden the first country in the world to grant women the right to vote.[120] This was after the introduction of a new political system, where a new local authority was introduced: the communal municipal council. The right to vote in municipal elections applied only to people of legal majority, which excluded married women, as they were juridically under the guardianship of their husbands. In 1884 the suggestion to grant women the right to vote in national elections was initially voted down in Parliament.[164] During the 1880s, the Married Woman's Property Rights Association had a campaign to encourage the female voters, qualified to vote in accordance with the 1862 law, to use their vote and increase the participation of women voters in the elections, but there was yet no public demand for women's suffrage among women. In 1888, the temperance activist Emilie Rathou became the first woman in Sweden to demand the right for women's suffrage in a public speech.[165] In 1899, a delegation from the Fredrika Bremer Association presented a suggestion of women's suffrage to prime minister Erik Gustaf Boström. The delegation was headed by Agda Montelius, accompanied by Gertrud Adelborg, who had written the demand. This was the first time the Swedish women's movement themselves had officially presented a demand for suffrage.

In 1902 the Swedish Society for Woman Suffrage was founded. In 1906 the suggestion of women's suffrage was voted down in parliament again.[166] In 1909, the right to vote in municipal elections were extended to also include married women.[167] The same year, women were granted eligibility for election to municipal councils,[167] and in the following 1910–11 municipal elections, forty women were elected to different municipal councils,[166] Gertrud Månsson being the first. In 1914 Emilia Broomé became the first woman in the legislative assembly.[168]

The right to vote in national elections was not returned to women until 1919, and was practised again in the election of 1921, for the first time in 150 years.[124]

After the 1921 election, the first women were elected to Swedish Parliament after women's suffrage were Kerstin Hesselgren in the Upper chamber and Nelly Thüring (Social Democrat), Agda Östlund (Social Democrat) Elisabeth Tamm (liberal) and Bertha Wellin (Conservative) in the Lower chamber. Karin Kock-Lindberg became the first female government minister, and in 1958, Ulla Lindström became the first acting Prime Minister.[169]

Switzerland

A referendum on women's suffrage was held on 1 February 1959. The majority of Switzerland's men (67%) voted against it, but in some French-speaking cantons women obtained the vote.[170] The first Swiss woman to hold political office, Trudy Späth-Schweizer, was elected to the municipal government of Riehen in 1958.[171]

Switzerland was the last Western republic to grant women's suffrage; they gained the right to vote in federal elections in 1971 after a second referendum that year.[170] In 1991 following a decision by the Federal Supreme Court of Switzerland, Appenzell Innerrhoden became the last Swiss canton to grant women the vote on local issues.[172]

The first female member of the seven-member Swiss Federal Council, Elisabeth Kopp, served from 1984 to 1989. Ruth Dreifuss, the second female member, served from 1993 to 1999, and was the first female President of the Swiss Confederation for the year 1999. From 22 September 2010 until 31 December 2011 the highest political executive of the Swiss Confederation had a majority of female councillors (4 of 7); for the three years 2010, 2011, and 2012 Switzerland was presided by female presidency for three years in a row; the latest one was for the year 2017.[173]

Turkey

.jpg)

In Turkey, Atatürk, the founding president of the republic, led a secularist cultural and legal transformation supporting women's rights including voting and being elected. Women won the right to vote in municipal elections on March 20, 1930. Women's suffrage was achieved for parliamentary elections on December 5, 1934, through a constitutional amendment. Turkish women, who participated in parliamentary elections for the first time on February 8, 1935, obtained 18 seats.

In the early republic, when Atatürk ran a one-party state, his party picked all candidates. A small percentage of seats were set aside for women, so naturally those female candidates won. When multi-party elections began in the 1940s, the share of women in the legislature fell, and the 4% share of parliamentary seats gained in 1935 was not reached again until 1999. In the parliament of 2011, women hold about 9% of the seats. Nevertheless, Turkish women gained the right to vote a decade or more before women in such Western European countries as France, Italy, and Belgium – a mark of Atatürk's far-reaching social changes.[174]

United Kingdom

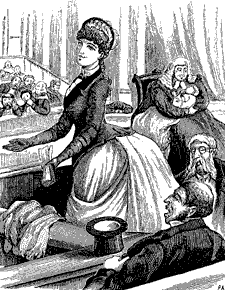

The campaign for women's suffrage in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland gained momentum throughout the early part of the 19th century, as women became increasingly politically active, particularly during the campaigns to reform suffrage in the United Kingdom. John Stuart Mill, elected to Parliament in 1865 and an open advocate of female suffrage (about to publish The Subjection of Women), campaigned for an amendment to the Reform Act 1832 to include female suffrage.[175] Roundly defeated in an all-male parliament under a Conservative government, the issue of women's suffrage came to the fore.

Until the 1832 Reform Act specified "male persons", a few women had been able to vote in parliamentary elections through property ownership, although this was rare.[176] In local government elections, women lost the right to vote under the Municipal Corporations Act 1835. Single women ratepayers received the right to vote in the Municipal Franchise Act 1869. This right was confirmed in the Local Government Act 1894 and extended to include some married women.[177][178][179][180] By 1900, more than 1 million single women were registered to vote in local government elections in England.[177]

In 1881, the Isle of Man (in the British Isles but not part of the United Kingdom) passed a law giving the vote to single and widowed women who passed a property qualification. This was to vote in elections for the House of Keys, in the Island's parliament, Tynwald. This was extended to universal suffrage for men and women in 1919.[181]

During the later half of the 19th century, a number of campaign groups for women's suffrage in national elections were formed in an attempt to lobby Members of Parliament and gain support. In 1897, seventeen of these groups came together to form the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), who held public meetings, wrote letters to politicians and published various texts.[182] In 1907 the NUWSS organized its first large procession.[182] This march became known as the Mud March as over 3,000 women trudged through the streets of London from Hyde Park to Exeter Hall to advocate women's suffrage.[183]

In 1903 a number of members of the NUWSS broke away and, led by Emmeline Pankhurst, formed the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU).[184] As the national media lost interest in the suffrage campaign, the WSPU decided it would use other methods to create publicity. This began in 1905 at a meeting in Manchester's Free Trade Hall where Edward Grey, 1st Viscount Grey of Fallodon, a member of the newly elected Liberal government, was speaking.[185] As he was talking, Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney of the WSPU constantly shouted out, "Will the Liberal Government give votes to women?"[185] When they refused to cease calling out, police were called to evict them and the two suffragettes (as members of the WSPU became known after this incident) were involved in a struggle which ended with them being arrested and charged for assault.[186] When they refused to pay their fine, they were sent to prison for one week, and three days.[185] The British public were shocked and took notice at this use of violence to win the vote for women.

After this media success, the WSPU's tactics became increasingly violent. This included an attempt in 1908 to storm the House of Commons, the arson of David Lloyd George's country home (despite his support for women's suffrage). In 1909 Lady Constance Lytton was imprisoned, but immediately released when her identity was discovered, so in 1910 she disguised herself as a working class seamstress called Jane Warton and endured inhumane treatment which included force-feeding. In 1913, suffragette Emily Davison protested by interfering with a horse owned by King George V during the running of The Derby; she was trampled and died four days later. The WSPU ceased their militant activities during World War I and agreed to assist with the war effort.[187]

The National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies, which had always employed "constitutional" methods, continued to lobby during the war years, and compromises were worked out between the NUWSS and the coalition government.[188] The Speaker's Conference on electoral reform (1917) represented all the parties in both houses, and came to the conclusion that women's suffrage was essential. Regarding fears that women would suddenly move from zero to a majority of the electorate due to the heavy loss of men during the war, the Conference recommended that the age restriction be 21 for men, and 30 for women.[189][190][191]