Male gaze

In feminist theory, the male gaze is the act of depicting women and the world, in the visual arts[1] and in literature,[2] from a masculine, heterosexual perspective that presents and represents women as sexual objects for the pleasure of the male viewer.[3] In the visual and aesthetic presentations of narrative cinema, the male gaze has three perspectives: (i) that of the man behind the camera, (ii) that of the male characters within the film's cinematic representations; and (iii) that of the spectator gazing at the image.[4][5]

The film critic Laura Mulvey coined the term male gaze, which is conceptually contrasted with and opposed by the female gaze.[6][7] As a way of seeing women and the world, the psychology of the male gaze is comparable to the psychology of scopophilia, the pleasure of looking; thus, the terms scopophilia and scoptophilia identify both the aesthetic pleasures and the sexual pleasures derived from looking at someone or something.[8]:815

Background

The existentialist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre introduced the concept of le regard, the gaze, in Being and Nothingness (1943), wherein the act of gazing at another human being creates a subjective power difference, which is felt by the gazer and by the gazed, because the person being gazed at is perceived as an object, not as a human being.[9] The cinematic concept of the male gaze is presented, explained, and developed in the essay "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema" (1975), in which Laura Mulvey proposes that sexual inequality — the asymmetry of social and political power between men and women — is a controlling social force in the cinematic representations of the sexes; and that the male gaze (the aesthetic pleasure of the male viewer) is a social construct derived from the ideologies and discourses of patriarchy.[10][8] In the fields of media studies and feminist film theory, the male gaze is conceptually related to the behaviours of voyeurism (looking as sexual pleasure), scopophilia (pleasure from looking), and narcissism (pleasure from contemplating one's self).

In a narrative film, the visual perspective of the male gaze is the sight-line of the camera as the spectator's perspective — that of a heterosexual man whose sight lingers upon the features of a woman's body.[11] In narrative cinema, the male gaze usually displays the female character (woman, girl, child) on two levels of eroticism: (i) as an erotic object of desire for the characters in the filmed story; and (ii) as an erotic object of desire for the male viewer (spectator) of the filmed story. Such visualizations establish the roles of dominant-male and dominated-female, by representing the female as a passive object for the male gaze of the active viewer. The social pairing of the passive-object (woman) and the active-viewer (man) is a functional basis of patriarchy, i.e. gender roles that are culturally reinforced in and by the aesthetics (textual, visual, representational) of mainstream, commercial cinema; the movies of which feature the male gaze as more important than the female gaze, an aesthetic choice based upon the inequality of socio-political power between men and women.[8]:14[6]:127

As an ideological basis of patriarchy, socio-political inequality is realised as a value system, by which male-created institutions (e.g the movie business, advertising, fashion) unilaterally determine what is "natural and normal" in society.[12] In time, the people of a society believe that the artificial values of patriarchy, as a social system, are the "natural and normal" order of things in society, because men look at women and women are looked at by men; hence the Western hierarchy of "inferior women" and "superior men" derives from misrepresenting men and women as sexual opponents, rather than as sexual equals.[12]

Concepts

_(cropped).jpg)

Scopophilia

Two forms of the male gaze are based upon the Freudian concept of scopophilia, the "pleasure that is linked to sexual attraction (voyeurism in the extreme) and [the] scopophilic pleasure that is linked to narcissistic identification (the introjection of ideal egos)", which show how women have been forced to view the cinema from the perspectives (sexual, aesthetic, cultural) of the male gaze. In such cinematic representations, the male gaze denies the female's agency and human identity, thus dehumanizing a woman, from person to object, to be considered only for her beauty, physique, and sex appeal, as defined in the male sexual fantasy of narrative cinema.[8]

Spectatorship

Two types of spectatorship occur whilst viewing a film, wherein the viewer either unconsciously or consciously engages in the typical, ascribed societal roles of men and women. In relation to phallocentrism, a film can be viewed from the perspectives of "three different looks": (i) the first look is that of the camera, which records the events of the film; (ii) the second look describes the nearly voyeuristic act of the audience as they view the film proper; and (iii) the third look is that of the characters who interact with one another throughout the filmed story. The perspective common to the three types of look is the idea that looking generally is perceived as the active role of the male, while being looked-at generally is perceived as the passive role of the female. Therefore, based upon that patriarchal construction, the cinema presents and represents women as objects of desire, wherein women characters have an "appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact"; therefore, the actress is never meant to represent a decisive female character whose actions directly affect the outcome of the plot or impel the events of the filmed story, but, instead, she is in the film to visually support the actor, portraying the male protagonist, by "bearing the burden of sexual objectification", a condition unbearable for the actor.[8]

A woman being the passive object of the male gaze is the link to scopophilia, to the aesthetic pleasure derived from looking at someone as an object of beauty. As an expression of sexuality, scopophilia refers to the pleasure (sensual and sexual) derived from looking at sexual fetishes and photographs, pornography and naked bodies, etc. There are two categories of pleasurable viewing: (i) voyeurism, wherein the viewer's pleasure is in looking at another person from a distance, and he or she projects fantasies, usually sexual, onto the gazed upon person; and (ii) narcissism, wherein the viewer's pleasure is in self-recognition when viewing the image of another person. That in order to enjoy a film as a woman, or as a person of any gender other than the male gender, women must learn to identify with the male protagonist and assume his perspective, the male gaze.[8] In the genre of action films, the dramaturg Wendy Arons said that the hyper-sexualization of female characters symbolically diminishes the threat of emasculation posed by violent women, hence: "The focus on the [woman's] body — as a body in ostentatious display of breasts, legs, and buttocks — does mitigate the threat that women pose to 'the very fabric of . . . society', by reassuring the [male] viewer of his male privilege, as the possessor of the objectifying [male] gaze."[13]

The female gaze

The female gaze is conceptually equal to the male gaze; that is, when women objectify a person, they view other people, and themselves, from the perspective of a man.[6] The male gaze is a manifestation of unequal social power, between the gazing man and the gazed-upon woman; and also is a conscious or subconscious social effort to develop gender inequality in service to a patriarchical sexual order. From either perspective, a woman who welcomes the sexual objectification of the male gaze might be perceived as conforming to social norms established for the benefit of men, thereby reinforcing the objectifying power of the male gaze upon woman; or, she might be perceived as an exhibitionist woman taking social advantage of the sexual objectification inherent to the male gaze, in order to manipulate the sexist norms of the patriarchy to her personal benefit.[6]

Mulvey said that the female gaze is analogous to the male gaze, because "the male figure cannot bear the burden of sexual objectification. Man is reluctant to gaze at his exhibitionist like."[14][15][16] In describing the relationships between the characters of the novel Wide Sargasso Sea (1966), by Jean Rhys, Nalini Paul said that when the character of Antoinette gazes at Rochester, and places a garland upon him, she makes him appear heroic, yet: "Rochester does not feel comfortable with having this role enforced upon him; thus, he rejects it by removing the garland, and crushing the flowers."[6] From the male perspective, a man possesses the gaze because he is a man, whereas a woman possesses the gaze only when she assumes the role of a man, and thus possesses the male gaze when she objectifies other people, by gazing at them as would a man.

Eva-Maria Jacobsson concurs with Paul's description of the female gaze as "a mere cross-identification with masculinity", yet evidence of women's sexual objectification of men — the existence of a discrete female gaze — can be found in the boy toy adverts in teen magazines. Despite Mulvey's contention that "the gaze" is a property of one gender or if the female gaze merely is an internalized male gaze remains indeterminate: "First, that the 1975 article 'Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema' was written as a polemic, and, as Mandy Merck has described it, as a manifesto; so I had no interest in modifying the argument. Clearly, I think, in retrospect, from a more nuanced perspective, [the article is] about the inescapability of the male gaze."[6]:128 Moreover, in the power dynamics of human relationships, the gazer can gaze upon members of the same gender for asexual reasons, such as comparing the gazer's body image and clothing to the body and clothes of the gazed-upon person.[6]:127[17]

Criticism

Matrixial gaze

Bracha Ettinger criticized the male gaze with the matrixial gaze, which is inoperative when the male gaze is opposite to the female gaze, wherein both perspectives constitute each other from a lack, which is the Lacanian definition of "The Gaze".[18] The matrixial gaze does not concern a subject and its object existing or lacking, but concerns "trans-subjectivity" and shareability, and is based upon the feminine-matrixial-difference, which escapes the phallic opposition of masculine–feminine, and is produced by co-emergence. Parting from Lacan's latter work, Ettinger's perspective is about the structure of the Lacanian subject, itself, which is deconstructed, and thus produces a perspective of feminine dimension with a hybrid, floating matrixial gaze.[19]

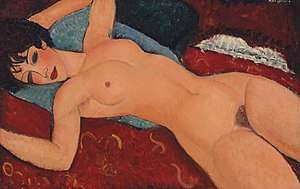

Seeing the nude woman

In the television series and book Ways of Seeing (1972), the art critic John Berger addressed the sexual objectification of women in the arts by emphasizing that men look and women are looked-at as the subjects of art. For the purposes of art-as-spectacle, men act and women are acted-upon according to the social conditions of spectatorship, which are determined by the artistic and aesthetic conventions of objectification, which artists have not transcended. Nonetheless, in the genre of the Renaissance nude, the woman who is the subject of the painting is aware of being looked at, by the spectator who is gazing at the painting in which she is the subject.[21]

In the production of art, the conventions of artistic representation connect the objectification of a woman, by the male gaze, to the Lacanian theory of social alienation — the psychological splitting that occurs from seeing one's self as one is, and seeing one's self as an idealized representation. In Italian Renaissance painting, especially in the nude-woman genre, that perceptual split arises from being both the viewer and the viewed, and from seeing one's self through the gaze of other people.[22]

The female gaze

The cultural analyst Griselda Pollock said that the female gaze can be visually negated;[23] using the example of Robert Doisneau's photograph Sidelong Glance (1948) Pollock describes a bourgeois, middle-aged couple viewing artworks in the display window of an art gallery. In the photograph, the spectator's perspective is from inside the art gallery. The couple are looking in directions different from that of the spectator. The woman is speaking to her husband about a painting at which she is gazing, whilst her distracted husband is gazing at a painting of a nude woman, which also is in view of the spectator. The woman is looking at another artwork, which is not in view of the spectator. The man's gaze has found someone more interesting to gaze at, thus ignoring his wife's comment. Pollock's analysis of the Sidelong Glance photograph is that: "She [the wife] is contrasted, iconographically, to the naked woman. She is denied the picturing of her desire; what she looks at is blank for the spectator. She is denied being the object of desire, because she is represented as a woman who actively looks, rather than [as a woman passively] returning and confirming the gaze of the masculine spectator."[23][24]

In "Watching the Detectives: The Enigma of the Female Gaze" (1989), Lorraine Gamman said that the female gaze is distinguished from the male gaze through its displacement of the power of scopophilia, which creates the possibility of multiple viewing angles, because "the female gaze cohabits the space occupied by men, rather than being entirely divorced from it"; therefore, the female gaze does not appropriate the "voyeurism" of the male gaze, because its purpose is to disrupt the phallocentric power of the male gaze, by providing other modes of looking at someone.[25]

In "Networks of Remediation" (1999), Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin said that Mulvey's male gaze coincides with "the desire for visual immediacy" — the erasure of the visual medium for uninhibited interaction with the person portrayed — which is identified in feminist film theory as the "male desire that takes an overt sexual meaning when the object of representation, and therefore desire, is a woman."[26]:79 Bolter and Grusin proposed the term hypermediacy — drawing the spectator's attention to the medium (or media) and to the process of mediation present in an artwork — to be a form of the female gaze, because it "is multiple and deviant in its suggestion of multiplicity — a multiplicity of viewing positions, and a multiplicity of relationships, to the object in view, including sexual objects"; thus, like the female gaze, hypermediacy disrupts the myopic and monolithic male gaze, by offering more angles of viewing.[26]:84

Photographer Farhat Basir Khan said that the female gaze is inherent to photographs taken by a woman, which perspective negates the stereotypical the male-gaze perspective inherent to "male-constructed" photographs, which, in the history of art, have presented and represented women as objects, rather than as persons. [27] The female gaze was the subject of the Feminigraphy exhibition, curated by Khan, at the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts in January 2017.

Oppositional gaze

In the essay "The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators" (1997)[28] bell hooks argues that Black women are placed outside the "pleasure in looking" by being excluded as subjects of the male gaze.[28] From her interpretation of Mulvey's essay "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema" (1975),[29] hooks said that "from a standpoint that acknowledges race, one sees clearly why Black women spectators, not duped by mainstream cinema, would develop an oppositional gaze" to the male gaze.[28] In relation to Lacan's mirror stage, during which a child develops the capacity for self-recognition, and thus the ideal ego, the oppositional gaze functions as a form of looking back, in search of the Black female body within the cinematic idealization of white womanhood.[28]

In the context of feminist theory, the absence of discussion of racial relations, within the "totalizing category [of] Women", is a process of denial which refutes the reality that the criticism of many feminist film critics concerns only the cinematic presentation and representation of white women.[28] In the course of being interviewed by hooks, a working-class Black woman said that "to see black women in the position [that] white women have occupied in film forever . . .", is to see a transfer without transformation;[28] therefore, the oppositional gaze encompasses intellectual resistance, and understanding and awareness of the politics of race and of racism via cinematic whiteness, inclusive of the male gaze.

See also

References

- "Feminist Aesthetics". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Winter 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

Assumes a standard point of view that is masculine and heterosexual. . . . The phrase 'male gaze' refers to the frequent framing of objects of visual art so that the viewer is situated in a masculine position of appreciation.

- That the male gaze applies to literature and to the visual arts: Łuczyńska-Hołdys, Małgorzata (2013). Soft-Shed Kisses: Re-visioning the Femme Fatale in English Poetry of the 19th Century, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, p. 15.

- Eaton, E.W. (September 2008). "Feminist Philosophy of Art". Philosophy Compass. Wiley-Blackwell. 3 (5): 873–893. doi:10.1111/j.1747-9991.2008.00154.x.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Devereaux, Mary (1995). "Oppressive Texts, Resisting Readers, and the Gendered Spectator: The "New" Aesthetics". In Brand, Peggy Z.; Korsmeyer, Carolyn (eds.). Feminism and tradition in aesthetics. University Park, Pennsylvania: Penn State University Press. p. 126. ISBN 9780271043968.

- Walters, Suzanna Danuta (1995). "Visual Pressures: On Gender and Looking". In Walters, Suzanna Danuta (ed.). Material Girls: Making Sense of Feminist Cultural Theory. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 57. ISBN 9780520089778.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sassatelli, Roberta (September 2011). "Interview with Laura Mulvey: Gender, Gaze and Technology in Film Culture". Theory, Culture & Society. 28 (5): 123–143. doi:10.1177/0263276411398278.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jacobsson, Eva-Maria (1999). A Female Gaze? (pdf) (Report). Stockholm, Sweden: Royal Institute of Technology. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-10-04.

- Mulvey, Laura (Autumn 1975). "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema". Screen. 16 (3): 6–18. doi:10.1093/screen/16.3.6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) Also available as: Mulvey, Laura (2009), "Visual pleasure and narrative cinema", in Mulvey, Laura (ed.), Visual and other pleasures (2nd ed.), Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire England New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 14–30, ISBN 9780230576469.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) Pdf via Amherst College. Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Stack, George J; Plant, Robert W (1982). "The Phenomenon of "The Look"". Philosophy and Phenomenological Research. 42 (3): 359. doi:10.2307/2107492. JSTOR 2107492.

By their presence -- most forcibly by looking into your eyes -- other people compel you to realize that you are an object for them, Sartre (1948) argues.

- Weeks, L. Paul (2005), "Male gaze", in Ritzer, George (ed.), Encyclopedia of social theory, Thousand Oaks, California: Sage, p. 467, ISBN 9780761926115.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) Preview.

- Streeter, Thomas; Hintlian, Nicole; Chipetz, Samantha; Callender, Susanna (2005). "This is Not Sex: A Web Essay on the Male Gaze, Fashion Advertising, and the Pose". Archived from the original on 2011-11-06. Essay about the male gaze in advertising.

- Pritchard, Annette; Morgan, Nigel J. (October 2000). "Privileging the Male Gaze: Gendered Tourism Landscapes". Annals of Tourism Research. 27 (4): 884–905. doi:10.1016/S0160-7383(99)00113-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Arons, Wendy, "If Her Stunning Beauty Doesn't Bring You to Your Knees, Her Deadly Drop-kick Will": Violent Women in Hong Kong Kung fu Film", in McCaughey, Martha; King, Neal (eds.), Reel Knockouts: Violent Women in the Movies, Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press, p. 41.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jacobsson, Eva-Maria (1999). A Female Gaze? (pdf) (Report). Stockholm, Sweden: Royal Institute of Technology. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-10-04.

- Paul, Nalini (Spring 2004). "Other Ways of Looking: The Female Gaze in Jean Rhys' Wide Sargasso Sea". ESharp. University of Glasgow. 2. Archived from the original on 27 January 2009.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kelly, Eileen (30 January 2003). "The Female Gaze". Salon. Salon Media Group. Archived from the original on 1 February 2003.

- Felluga, Dino (April 2005). ""Modules on Lacan: On the Gaze", Introductory Guide to Critical Theory". West Lafayette, Indiana, U.S.: Purdue University. Archived from the original on 15 April 2005.

- Ettinger, Bracha (1995). The Matrixial Gaze. Leeds, UK: Feminist Arts and Histories Network, Department of Fine Art, University of Leeds. ISBN 9780952489900.

- Ettinger, Bracha (1996), "The With-in-visible Screen", in de Zegher, M. Catherine (ed.), Inside the Visible: An Elliptical Traverse of 20th century Art In, Of, and From the Feminine, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, pp. 89–116, ISBN 9780262540810.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Berger, John Ways of Seeing (1972) pp. 45, 47.

- Berger, John (1973), "Section 3", in Berger, John (ed.), Ways of Seeing, London: BBC Penguin Books, pp. 45 and 47, ISBN 9780563122449.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sturken, Marita; Cartwright, Lisa (2001), "Spectatorship, Power, and Knowledge", in Sturken, Marita; Cartwright, Lisa (eds.), Practices of Looking: An Introduction to Visual Culture, Oxford New York: Oxford University Press, p. 81, ISBN 9780198742715.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pollock, Griselda (1988), "Modernity and the Spaces for Femininity", in Pollock, Griselda (ed.), Vision and Difference: Femininity, Feminism, and Histories of Art, London New York: Routledge, pp. 50–90, ISBN 9780415007214.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Abridgement available at: Pollock, Griselda (1992), "Modernity and the Spaces for Femininity", in Broude, Norma; Garrard, Mary D. (eds.), The Expanding Discourse: Feminism and Art History, New York City, New York: Icon Editions, pp. 245–267, ISBN 9780064302074.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) Pdf.

- Vidani, Peter. "A Collection on Feminism and Design — Photograph: Robert Doisneau, Sidelong Glance (1948))". gorillagirls.tumblr.com. Gorilla Girls. Archived from the original on 30 January 2016. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- Gamman, Lorraine (1989), "Watching the Detectives: The Enigma of the Female Gaze", in Gamman, Lorraine; Marshment, Margaret (eds.), The Female Gaze: Women as Viewers of Popular Culture, Seattle: Real Comet Press, p. 16, ISBN 9780941104425.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bolter, Jay David; Grusin, Richard (1999), "Networks of Remediation", in Bolter, Jay David; Grusin, Richard (eds.), Remediation Understanding New Media, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, pp. 64–87, ISBN 9780262024525.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Khan, Atif (2017-01-04). "From Her Perspective". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 2 June 2018. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- hooks, bell. "The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators". The Feminism and Visual Cultural Reader. New York: Routledge, 2003: Amelia Jones. pp. 94–105.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Mulvey, Laura. "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema". Media and Cultural Studies: Keywords. 2001; Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2006: Meenakshi Gigi Durham and Douglas Kellner. pp. 342–352.CS1 maint: location (link)

Further reading

- Neville, Lucy (July 2015). "Male gays in the female gaze: women who watch m/m pornography" (PDF). Porn Studies. 2 (2–3): 192–207. doi:10.1080/23268743.2015.1052937.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)