Guru Granth Sahib

Guru Granth Sahib (Punjabi: ਗੁਰੂ ਗ੍ਰੰਥ ਸਾਹਿਬ Punjabi pronunciation: [ɡʊɾuː ɡɾəntʰᵊ saːhɪb]) is the central religious scripture of Sikhism, regarded by Sikhs as the final, sovereign and eternal living Guru following the lineage of the ten human gurus of the religion. The Adi Granth, its first rendition, was compiled by the fifth Guru, Guru Arjan (1563–1606). Guru Gobind Singh, the tenth Sikh Guru, did not add any of his own hymns; however, he added all 115 hymns of Guru Tegh Bahadur, the ninth Sikh Guru, to the Adi Granth and affirmed the text as his successor.[1] This second rendition became known as Guru Granth Sahib and is sometimes also referred to as Adi Granth.[2][3]

| Guru Granth Sahib | |

|---|---|

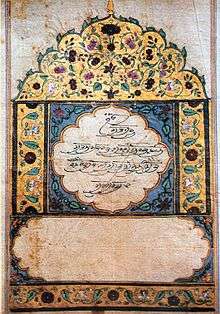

Illuminated Guru Granth Sahib folio with nisan (Mul Mantar) of Guru Nanak | |

| Information | |

| Religion | Sikhism |

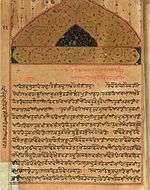

The text consists of 1,430 angs (pages) and 5,894 śabads (line compositions),[4][5][6] which are poetically rendered and set to a rhythmic ancient north Indian classical form of music.[7] The bulk of the scripture is divided into sixty[4][5] rāgas, with each Granth rāga subdivided according to length and author. The hymns in the scripture are arranged primarily by the rāgas in which they are read.[5] The Guru Granth Sahib is written in the Gurmukhi script, in various languages, including Lahnda (Western Punjabi), Braj Bhasha, Kauravi, Sanskrit, Sindhi, and Persian. Copies in these languages often have the generic title of Sant Bhasha.[8]

Guru Granth Sahib was composed predominantly by six Sikh Gurus: Guru Nanak, Guru Angad, Guru Amar Das, Guru Ram Das, Guru Arjan, and Guru Teg Bahadur. It also contains the poetic teachings of thirteen Hindu Bhakti movement sant poets and two Sufi Muslim poets.[9][10]

The vision in the Guru Granth Sahib is of a society based on divine justice without oppression of any kind.[11][12] While the Granth acknowledges and respects the scriptures of Hinduism and Islam, it does not imply a moral reconciliation with either of these religions.[13] It is installed in a Sikh gurdwara (temple). A Sikh typically bows or prostrates before it on entering such a temple.[14] The Granth is revered as eternal gurbānī and the spiritual authority in Sikhism.[15]

History

| Part of a series on |

| Sikh scriptures |

|---|

|

| Guru Granth Sahib |

| Dasam Granth |

|

| Sarbloh Granth |

| Varan Bhai Gurdas |

Guru Nanak composed hymns, which were sung by his followers in rāga set to music.[16] His successor, Guru Angad, opened centers and distributed these hymns. The community would sing the hymns and his agents collected donations.[17] This tradition was continued by the third and fourth gurus as well. The fifth guru, Guru Arjan, discovered that Prithi Chand – his eldest brother and a competing claimant to the Sikh guruship - had a copy of an earlier pothi (palm-leaf manuscript) with hymns and was distributing hymns of the earlier Gurus along with his own of hymns.[18] Guru Arjan considered these as spurious and became concerned about establishing an authentic anthology of approved hymns.[19]

Guru Arjan began compiling an officially approved version of the sacred scripture for the Sikh community. He sent his associates across the Indian subcontinent to collect the circulating hymns of Sikh Gurus and convinced Mohan, the son of Guru Amar Das, to give him the collection of the religious writings of the first three gurus.[19] As his associates returned with their collections, Guru Arjan selected and edited the hymns for inclusion in the Adi Granth with Bhai Gurdas as his scribe.[20][note 1] This effort yielded several drafts and manuscripts, some of which have survived into the modern era.[18][22]

The oldest surviving manuscript version of the Adi Granth is the Guru Nanak Dev University Manuscript 1245 and has been dated to c. 1599. Other early editions of Adi Granth with some variations include the Bahoval pothi (c. 1600), Vanjara pothi (c. 1601) and Bhai Rupa pothi (c. 1603).[22]

Another early variant manuscript is called the Guru Harsahai pothi, preserved by Sodhis and is believed to be the one that existed before Guru Arjan's compilation and one he gave to his eldest brother Prithi Chand. It was initially installed in Amritsar, then was moved in the 18th-century and preserved in Guru Harsahai (35 kilometers west of Faridkot, Punjab) till 1969, when the state government requested it be displayed for the 500 years celebrations. It was moved for the first time in over 200 years and briefly displayed in Patiala for the event. Thereafter, the Sodhis consented to transfers. In 1970, however, during another such transfer, this early version of the Adi Granth manuscript was stolen.[18] However, photos of some pages have survived.

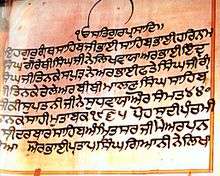

This manuscript is claimed by the Sodhis to be the oldest and one written in part by Guru Nanak. However, this claim is first observed only much later, in texts attributed to the 17th-century Hariji, the grandson of Prithi Chand. Based on the evidence in the surviving photos, it is unlikely that Guru Nanak wrote or maintained a pothi. The features in its Gurmukhi script and the language suggest that the hymns are significantly older, and that the pre-canonical hymns were being written down in early Sikhism and preserved by the Sikh Gurus prior to the editing by Guru Arjan. The existence of Guru Harsahai manuscript attests to the early tradition of Sikh scripture, its existence in variant forms and a competition of ideas on its contents including the Mul Mantar.[23]

Many minor variations, and three significant Adi Granth recensions are known and these provide insights into how the Sikh scripture was compiled, edited and revised over time.[22] There is a fourth significant version called the Lahori bir, but it primarily differs in how the hymns are arranged and the final pages of the Adi Granth.[22][note 2]

Editions

In 1604, the first edition of the Sikh scripture, Adi Granth, was complete and officially approved by Guru Arjan. It was installed at the Golden Temple, with Baba Buddha as the first granthi or reader.[27] No hymns were added by Guru Hargobind, Guru Har Rai and Guru Har Krishan. In the Sikh tradition, Guru Hargobind is credited for adding the rāga tunes for nine out of 22 Vars. The hymns of IX Guru Tegh Bahadur, after his beheading in Delhi, were added to the scripture by his son and successor Guru Gobind Singh.[21]

In 1704 at Damdama Sahib, during a one-year respite from the heavy fighting with the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb, Guru Gobind Singh and Bhai Mani Singh added the religious compositions of Guru Tegh Bahadur to the Adi Granth to create the final edition called the Guru Granth Sahib.[28] Prior to Guru Gobind Singh, three versions of the Adi Granth pothi with minor variations were in circulation at Sikh shrines across the Indian subcontinent.[29] In addition, several unauthorized versions were in circulation, issued by sects founded by one of the sons or relatives of earlier Sikh Gurus such as Prithi Chand, Guru Arjan's elder brother.[29] Guru Gobind Singh issued the definitive final edition that included the hymns of his father, and closed the canon. This manuscript is called the Damdama bir, and a 1707 rare copy of this manuscript is now preserved at the Toshakhana in Nanded, Maharashtra.[29]

The compositions of Guru Gobind Singh were not included in Guru Granth Sahib and set into the Dasven Padsah ka Granth, which is more popularly known as the Dasam Granth.[28] The compilation and release of this definitive edition of the latter was completed by Bhai Mani Singh.[30]

Contributors

Number of hymns contributed to the Guru Granth Sahib[31]

The Guru Granth Sahib contains predominantly hymns of the following Sikh Gurus: Guru Nanak, Guru Angad, Guru Amar Das, Guru Ram Das, Guru Arjan, and Guru Teg Bahadur.[31] It also contains hymns and verses of thirteen Hindu Bhakti movement sant poets (saints) and two Muslim saint poets. There are also adulatory verses for the Gurus such as Guru Nanak fused into some pages, those composed by bards (Bhatts). The hymns and verses are different lengths, some very long, others being just a few line verses.[9][31] Twenty-two of the thirty-one ragas contain the contributions of bhagats.[2] The following is a list of contributors whose hymns are present in Guru Granth Sahib[32] as well as the number of hymns they contributed:[2]

- Guru Nanak Dev (974)

- Guru Angad Dev (62)

- Guru Amar Das (907)

- Guru Ram Das (679)

- Guru Arjan Dev (2218)

- Guru Tegh Bahadur (116)

Others:

- Bhagat Jayadeva (2)

- Bhagat Farid (134)

- Bhagat Ramanand (1)

- Bhagat Namdev (60)

- Bhagat Trilochan (5)

- Bhagat Parmanand (1)

- Bhagat Dhanna (4)

- Bhagat Bhikhan (2)

- Bhagat Beni (3)

- Bhagat Pipa (1)

- Bhagat Sain (1)

- Bhagat Surdas (1)

- Bhagat Sadhana (1)

- Bhagat Ravidas (41)

- Bhagat Kabir (541)

- Baba Sundar (6)

- Balvand Rai (1)

- Bhatt Kalshar (54)

- Bhatt Balh (1)

- Bhatt Bhalh (5)

- Bhatt Bhika (2)

- Bhatt Gayand (13)

- Bhatt Harbans (2)

- Bhatt Jalap (5)

- Bhatt Kirat (8)

- Bhatt Mathura (14)

- Bhatt Nalh (16)

- Bhatt Salh (3)

Manuscript versions

In the 19th and 20th-century, several manuscript versions of the Adi Granth and the Guru Granth Sahib hymns have been discovered. This has triggered contesting theories about authenticity and how the canonical text of Sikhism evolved over time. There are five views:[33]

- The first view held by scholars such as Balwant Singh Dhillon states that there was a consistent "mother tradition", where the hymns of Guru Nanak were carefully preserved as a single codex without any corruption or unauthorized changes, to which the later Gurus added additional hymns. The Sikh scripture developed in linear, pure form becoming first the Adi Granth and finally the closed version of the Guru Granth Sahib. According to this view, there were no pre-canonical diversity, the scripture developed in an organized and disciplined format, and it denies the existence of alternate hymns and texts that were cherished by Sikhs of an earlier era.[33]

- The second view held by scholars such as Gurinder Singh Mann states that the scripture started from a single process, proceeded linearly, then diversified into separate textual traditions with some variations, over time. This school of scholars supports their theory by highlighting the similarities of the manuscripts and close match particularly between the three manuscripts called the Guru Har Sahai MS, the Govindval MS, and the Guru Nanak Dev University MS 1245.[33] This theory is weakened by variations observed in 27 manuscript variants now dated between 1642 and 1692. The alternate formulation of this theory states that two branches developed over time, with the Peshawar pothi and Kartarpur pothi being the two branches.[33]

- The third view held by scholars such as Piar Singh states that independent versions of the Sikh scripture developed in geographically distant regions of the Indian subcontinent.[33] These versions developed because of the forgetfulness or creativity of the local Sikh leaders, errors made by scribes, attempts to adopt popular hymns of bhagats or adapt the hymns to local regional languages where Gurmukhi was not understood. It is these manuscripts that Guru Arjan collected and considered, then edited to produce an approved version of the Adi Granth. The Sikh scripture, according to this school, was thus a collaborative effort and there was no authentic version of the pre-canonical text in Sikhism.[33]

- The fourth view builds upon this third view and is supported by scholars such as Jeevan Deol. According to this view, there were independent textual traditions in Sikhism before Guru Arjan decided to edit and redact them into the Adi Granth.[33] These textual traditions developed in different parts of the Indian subcontinent, greatly influenced by the popularity of regional bhagats and their Bhakti movement ideas about nirguna and saguna forms of the divine, with Guru Arjan favoring the nirgun versions. The Adi Granth reflects the review, editing and compilation of complex and diverse textual traditions before him.[33]

- The fifth view held by scholars such as Pashaura Singh develops and refines the fourth view. It states that the Sikh scripture emerged from a collaborative effort of Guru Arjan and his trusted associates, particularly Bhai Gurdas and Jagana Brahmin of Agra. His collaborators were his devout admirers, well versed in the Sikh thought, Sanskrit traditions and philosophical schools of Indian religions.[34] The variant manuscripts support this theory, as does the handwriting analysis of the Kartarpur bir (manuscript) approved by Guru Arjan which shows at least four distinct scribal styles.[34] The variations in the manuscripts also affirm that the Adi Granth did not develop in a linear way, i.e. it was not simply copied from a previous version.[18][34]

Composition

The entire Guru Granth Sahib is written in the Gurmukhi script, which was standardized by Guru Angad in the 16th century. According to Sikh tradition and the Mahman Prakash, an early Sikh manuscript, Guru Angad Dev had taught and spread Gurmukhi at the suggestion of Guru Nanak Dev which has invented the Gurmukhi script.[35][36] The word Gurmukhī translates to "from the mouth of the guru". It descended from the Laṇḍā scripts and was used from the outset for compiling Sikh scriptures. The Sikhs assign a high degree of sanctity to the Gurmukhī script.[37] It is the official script for writing Punjabi in the Indian State of Punjab.

Gurus considered divine worship through shabad kirtan as the best means of attaining that state of bliss -vismad- which resulted in communion with God. The Guru Granth Sahib is divided by musical settings or rāgas[4] into 1430 pages known as angs "limbs" in Sikh tradition. It can be categorized into two sections:

- Introductory section consisting of the Mul Mantar, Japji Sahib and Sohila, composed by Guru Nanak;

- Compositions of Sikh gurus, followed by those of the bhagats who know only God, collected according to the chronology of ragas or musical settings. (see below).

The word raga refers to the "color"[38] and, more specifically, the emotion or mood produced by a combination or sequence of pitches.[39] A rāga is composed of a series of melodic motifs, based upon a definite scale or mode of the seven svara psalmizations,[40] that provide a basic structure around which the musician performs. Gurbani raags are not time dependent.

Following is the list of all sixty rāgas under which Gurbani is written, in order of appearance with page numbers:

- Asa — 8,

- Gujari — 10,

- Gauri Deepaki — 12,

- Dhanasri — 13,

- Gauri Poorabi — 13,

- Sri — 14,

- Majh — 94,

- Gauri Guarairee — 151,

- Gauri — 151,

- Gauri Dakhani — 152,

- Gauri Chaitee — 154,

- Gauri Bairagan — 156,

- Gauri Poorabi Deepaki — 157,

- Gauri Majh — 172,

- Gauri Malva — 214,

- Gauri Mala — 214,

- Gauri Sorath — 330,

- Asa Kafi — 365,

- Asavari — 369,

- Asa Asavari — 409,

- Devgandhari — 527,

- Bihagra — 537,

- Vadhans — 557,

- Vadhans Dakhani — 580,

- Sorath — 595,

- Jaitsri — 696,

- Todi — 711,

- Bairarri — 719,

- Tilang — 721,

- Tilang Kafi — 726,

- Suhee — 728,

- Suhee Kafi — 751,

- Suhee Lalit — 793,

- Bilaval — 795,

- Bilaval Dakhani — 843,

- Gound — 859,

- Bilaval Gound — 874,

- Ramkali — 876,

- Ramkali Dakhani — 907,

- Nut Narayan — 975,

- Nut — 975,

- Mali Gaura — 984,

- Maru — 989,

- Maru Kafi — 1014,

- Maru Dakhani — 1033,

- Tukhari — 1107,

- Kedara — 1118,

- Bhairo — 1125,

- Basant — 1168,

- Basant Hindol — 1170,

- Sarang — 1197,

- Malar — 1254,

- Kanra — 1294,

- Kaliyan — 1319,

- Kaliyan Bhopali — 1321,

- Parbhati Bibhas — 1327,

- Parbhati — 1327,

- Parbhati Dakhani — 1344,

- Bibhas Parbhati — 1347,

- Jaijavanti — 1352.

Meaning and role in Sikhism

In 1708, Guru Gobind Singh conferred the title of "Guru of the Sikhs" upon the Adi Granth. The event was recorded in a Bhatt Vahi (a bard's scroll) by an eyewitness, Narbud Singh, who was a bard at the Rajput rulers' court associated with gurus.[41] Sikhs since then have accepted Guru Granth Sahib, the sacred scripture, as their eternal-living guru, as the embodiment of the ten Sikh Gurus, the highest religious and spiritual guide for Sikhs. It plays a central role in guiding the Sikh's way of life.[3][42]

No one can change or alter any of the writings of the Sikh gurus written in the Guru Granth Sahib. This includes sentences, words, structure, grammar, and meanings. This tradition was set by Guru Har Rai. He sent his eldest son Ram Rai as an emissary to the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb in Delhi. Aurangzeb, a devout Muslim ruler, objected to a verse in the Sikh scripture (Asa ki Var) that stated, "the clay from a Musalman's grave is kneaded into potter's lump", considering it an insult to Islam. Ram Rai tried to please the emperor by explaining that the text was miscopied and modified it, substituting "Musalman" with "Beiman" (faithless, evil) which Aurangzeb approved.[43][44] The willingness to change a word led Guru Har Rai to bar his son from his presence, and name his younger son as his successor.[44]

Recitation

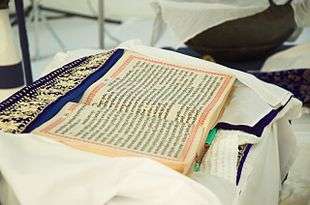

Guru Granth Sahib is always the focal point in any gurdwara, seated on a raised platform known as a Takht (throne), while the congregation of devotees sits on the floor and bow before the guru as a sign of respect. Guru Granth Sahib is given the greatest respect and honour. Sikhs cover their heads and remove their shoes while in the presence of this sacred scripture, their eternal living guru. Guru Granth Sahib is normally carried on the head and as a sign of respect, never touched with unwashed hands or put on the floor.[45] It is attended with all signs of royalty, with a canopy placed over it. A chaur (fan whisk) is waved above the Guru Granth Sahib.[46]

The Guru Granth Sahib is taken care of by a Granthi, who is responsible for reciting from the sacred hymns and leading Sikh prayers. The Granthi also acts as caretaker for the Guru Granth Sahib, keeping the Guru Granth Sahib covered in clean cloths, known as rumala, to protect from heat and dust. The Guru Granth Sahib rests on a manji sahib under a rumala until brought out again.[45]

Rituals

There are several rituals performed every day in major Sikh gurdwaras (temples) such as the Golden Temple. These rituals treat the scripture as a living person, a Guru out of respect. The rituals include:[47][48]

- Closing ritual called sukhasan (sukh means "comfort or rest", asan means "position"). At night, after a series of devotional kirtans and three part ardās, the Guru Granth Sahib is closed, carried on the head, placed into and then carried in a flower decorated, pillow-bed palki (palanquin), with chanting to its bedroom. Once it arrives there, the scripture is tucked into a bed.[47][48][note 3]

- Opening ritual called prakash which means "light". About dawn everyday, the Guru Granth Sahib is taken out its bedroom, carried on the head, placed and carried in a flower-decorated palki with chanting, sometimes with bugle sounding its passage. It is brought to the sanctum. Then after ritual singing of a series of Var Asa kirtans and ardas, a random page is opened. The first complete verse on the left page is the mukhwak (or vak) of the day. It is read out loud, and then written out for the pilgrims to read over that day.[47][48][49]

Translations

Ernest Trumpp – a German philologist, published the first philological study and a major but incomplete translation of the Guru Granth Sahib in 1877, after an 8-year study of the text and field interviews with Sikh intelligentsia of his time.[50][51] Trumpp included his criticism of the Sikh scripture in the preface and introductory sections, and stated "Sikhism is a waning religion, that will soon belong to history". Many in the Sikh community regarded these introductory remarks to his translation as "extremely offensive".[52][53] According to the Indologist Mark Juergensmeyer, setting aside Ernest Trumpp's nasty remarks, he was a German linguist and his years of scholarship, translations, as well as field notes and discussions with Sikhs at the Golden Temple remain valuable reference works for contemporary scholars.[54] While Akshaya Kumar holds Trumpp's translation to be "literal and mechanical" emphasizing preciseness and fastidiously retaining the words as well as the syntax of the original verses, avoiding any creative and inventive restatement to empathize with a believer,[55] Arvind-Pal Singh Mandair noted the clear influence from the Brahmanical leanings of his Nirmala collaborators,[56] among the British-supported Sikh class which had been long enjoying British patronage as they helped to keep “hostile” elements under control,[57] who for example induced Trumpp to omit the numeral “one” in the phrase Ik Oankar in his translation,[56] in an attempt to bring the scripture closer to the Brahmanical-influenced interpretation of the sects that differed with the interpretation of the orthodox Khalsa. Trumpp’s translation was seen to be a challenge to the administration’s already-established view that the Sikhs were a distinct community,[56] prompting the Khalsa to commission its own translation. Trumpp, as well as other translators, were commissioned by colonial administrators.[55]

Max Arthur Macauliffe – a British civil servant, was next to publish a major but incomplete translation of the Guru Granth Sahib, covering the same ground as Trumpp but interspersed his translation between Janamsakhis-based mythical history of the Sikh Gurus.[58][59] A major source of his historical information was Suraj Prakash of Santokh Singh, and his primary translation advisor was the prominent Khalsa Sikh scholar Kahn Singh Nabha – the author of Gurmat Prabhakar and Hum Hindu Nahin.[60][61] Macauliffe's translation appeared embedded in the six-volume The Sikh Religion and was published by Oxford University Press in 1909.[59] Unlike Trumpp who had disregarded the sensibilities and empathy for the Sikhs, Macauliffe used his creative editorial abilities to incorporate these sensibilities.[59] While Trumpp criticized Sikhism and the Guru Granth Sahib, Macauliffe criticized Hinduism and wrote an introduction that presented the hymns of Sikh Gurus as Christian-like with affinities to "Protestant virtues and ethics", presumably for a British audience, states Indologist Giorgio Shani.[62] Macauliffe's translation was well received by the Sikh community and considered by them as closer to how they interpret their scripture.[59] Post-colonial scholarship has questioned Macauliffe's accounting for and incorporation of Sikh traditions as "uncritical" and "dubious", though one that pleased the Sikh community.[59] Macauliffe's version has been widely followed by later scholars and translators.[59] According to Christopher Shackle – a scholar of Languages and Religion, Macauliffe's approach to translation was to work with Khalsa Sikh reformists of the 1890s (Singh Sabha) and exegetically present the scripture in a "progressive monotheism" fold that deserved the support of the British administration as a distinct tradition, and of the native Sikh clergy.[55] He used considerable freedom in restating the archaic poetry into a "vaguely psalm-like translation".[63]

ਹੁਕਮੀ ਹੋਵਨਿ ਆਕਾਰ ਹੁਕਮੁ ਨ ਕਹਿਆ ਜਾਈ ॥ ਹੁਕਮੀ ਹੋਵਨਿ ਜੀਅ ਹੁਕਮਿ ਮਿਲੈ ਵਡਿਆਈ ॥ ਹੁਕਮੀ ਉਤਮੁ ਨੀਚੁ ਹੁਕਮਿ ਲਿਖਿ ਦੁਖ ਸੁਖ ਪਾਈਅਹਿ ॥ ਇਕਨਾ ਹੁਕਮੀ ਬਖਸੀਸ ਇਕਿ ਹੁਕਮੀ ਸਦਾ ਭਵਾਈਅਹਿ ॥ ਹੁਕਮੈ ਅੰਦਰਿ ਸਭੁ ਕੋ ਬਾਹਰਿ ਹੁਕਮ ਨ ਕੋਇ ॥ ਨਾਨਕ ਹੁਕਮੈ ਜੇ ਬੁਝੈ ਤ ਹਉਮੈ ਕਹੈ ਨ ਕੋਇ ॥੨॥ |

Hukmī hovan ākār hukam na kahiā jāī. Hukmī hovan jīa hukam milai vadiāī. Hukmī utam nīch hukam likh dukh sukh pāīah. Iknā hukmī bakhsīs ik hukmī sadā bhavāīah. Hukmai andar sabh ko bāhar hukam na koe. Nānak hukmai je bujhai ta haumai kahai na koe. ॥2॥ |

| —Guru Granth Sahib Japji Sahib 2-3 [64] | —Transliteration |

Translation by Ernest Trumpp (1877)[65] |

Translation by Max Arthur Macauliffe (1909)[66] |

| —Guru Granth Sahib Japji Sahib 2-3 | —Guru Granth Sahib Japji Sahib 2-3 |

The first complete English translation of Guru Granth Sahib, by Gopal Singh, was published in 1960. A revised version published in 1978 removed the obsolete English words such as "thee" and "thou". In 1962, an eight-volume translation into English and Punjabi by Manmohan Singh was published by the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee. In the 2000s, a translation by Sant Singh Khalsa appeared on major Sikhism-related websites such as 3HO/Sikh Dharma Brotherhood's Sikhnet.com.[63]

Printing

The official versions of the Guru Granth Sahib are produced in Amritsar by Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC). The SGPC printers are only authorized worldwide publisher of the scripture, states the Sikh religious body Akal Takht.[67] Prior to 2006, Jeewan Singh Chattar Singh & Sons used to print the official versions and were the oldest publisher in Amritsar. However, in 2006, the Akal Takht banned them from printing the Sikh scripture after a sting operation showed that they were printing and mishandling the scripture as well as selling an illegal copy of the Sikh scripture to a Muslim seer.[68] A subsidiary of the SGPC, the Delhi Sikh Gurudwara Management Committee, is the authorized printer and supplier of the Guru Granth Sahib to Sikhs outside of India. These facilities are a part of the Gurudwara Rakabganj in New Delhi.[69]

The original Guru Granth Sahib is in the possession of the Sodhi family of Kartarpur village and is placed at Gurdwara Thum Sahib. The Sodhis are descendants of Guru Arjan Dev and Kartarpur was founded by him in 1598. Since the early 20th century, it has been printed in a standard edition of 1430 Angs. Prior to the late nineteenth century, only handwritten copies were prepared. The first printed copy of the Guru Granth Sahib was made in 1864. Any copies of Guru Granth Sahib deemed unfit to be read from are cremated, with a ceremony similar to that for cremating a deceased person. Such cremating is called Agan Bheta. Guru Granth Sahib is currently printed in an authorized printing press in the basement of the Gurudwara Ramsar in Amritsar; misprints and set-up sheets, and printer's waste with any of its sacred text on, are cremated at Goindval.[70]

Notes

- According to Khushwant Singh, while the manuscript was being put together, Akbar – the Mughal Emperor, received a report that the Adi Granth contained passages vilifying Islam. Therefore, he asked to inspect it.[21] Baba Buddha and Bhai Gurdas brought him a copy of the manuscript and read a few hymns from it. Akbar decided that this report had been false and donated 51 gold mohurs to the manuscript effort. However, this support for the Sikh scripture and Sikhism was short-lived once Akbar died, with Jehangir calling Sikhism as a "false traffic". Under his orders, Guru Arjan who compiled the first edition of the Sikh scripture was tortured and executed.[21]

- Another controversy has been the discovery of two blank folios in the Kartarpur manuscript (near page 703) and why the Ramakali hymn on that page is just two opening lines. In contrast to the Kartarpur manuscript, the Banno manuscript of Adi Granth discovered in Kanpur, and dated to 1644 CE, is identical in all respects but it has no blank pages and on the folio pages near 703 is a complete hymn. The Banno bir has been controversial because it includes many Hindu rites-of-passage (sanskara) in that version of the Adi Granth.[24] According to W.H. McLeod, the difference in the two versions can be because of three possibilities, from which he withholds judgment:[25] first, Guru Arjan deliberately left the blank folio pages to complete it later, but was unable to because he was arrested and executed by the Mughal emperor Jehangir; second, the hymn and pages existed in the original manuscript, the Banno bir is older, the pages were removed by Khalsa Sikhs from the Kartarpur manuscript and replaced with blank folios in their attempt to carve out a separate Sikh identity from the Hindus during the Singh Sabha Movement; third, the blank pages were intentionally left by Guru Arjan for unknown reasons, and the complete hymn in the Banno bir is an interpolation added by a Sikh follower who wanted to insert Brahminical rites-of-passage rituals in the text. According to G.B. Singh – a Sikh scholar who pioneered study of the early Sikh manuscripts, the evidence supports the second theory.[24][26] According to Pashaura Singh, his examination of the manuscripts and linguistic evidence yields support for the third theory, noting that the smaller hand and different writing implement in which the remaining 22 lines were written, the lines themselves do not match earlier manuscripts and differ in structure and lexicon from the rest of Guru Arjan's writings, the presence of other short verses in all manuscripts like Vār Basant with only three stanzas, and points to the fact that G.B. Singh had made the claim without actually examining the text, positing that he seemed to have been serving the interests of the Arya Samaj based on his writings.[24]

- In moderate size gurdwaras, the palanquin step may be skipped and the scripture is simply carried on the head to its bedroom.[49]

References

- Partridge, Christopher Hugh (2005). Introduction to World Religions. p. 223.

- Kapoor, Sukhbir. Guru Granth Sahib: An Advance Study. Hemkunt Press. p. 139. ISBN 9788170103219.

- Adi Granth, Encyclopaedia Britannica

- Brown, Kerry (1999). Sikh Art and Literature. Psychology Press. p. 200. ISBN 978-0-415-20289-3.

- Christopher Shackle and Arvind Mandair (2005), Teachings of the Sikh Gurus, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415266048, pages xvii-xx

- Penney, Sue. Sikhism. Heinemann. p. 14. ISBN 0-435-30470-4.

- Anna S. King and JL Brockington (2005), The Intimate Other: Love Divine in Indic Religions, Orient Blackswan, ISBN 978-8125028017, pages 359-361

- Harnik Deol, Religion and Nationalism in India. Routledge, 2000. ISBN 0-415-20108-X, 9780415201087. Page 22. "(...) the compositions in the Sikh holy book, Adi Granth, are a melange of various dialects, often coalesced under the generic title of Sant Bhasha."

The Making of Sikh Scripture by Gurinder Singh Mann. Published by Oxford University Press US, 2001. ISBN 0-19-513024-3, ISBN 978-0-19-513024-9 Page 5. "The language of the hymns recorded in the Adi Granth has been called Sant Bhasha, a kind of lingua franca used by the medieval saint-poets of northern India. But the broad range of contributors to the text produced a complex mix of regional dialects."

Surindar Singh Kohli, History of Punjabi Literature. Page 48. National Book, 1993. ISBN 81-7116-141-3, ISBN 978-81-7116-141-6. "When we go through the hymns and compositions of the Guru written in Sant Bhasha (saint-language), it appears that some Indian saint of 16th century...."

Nirmal Dass, Songs of the Saints from the Adi Granth. SUNY Press, 2000. ISBN 0-7914-4683-2, ISBN 978-0-7914-4683-6. Page 13. "Any attempt at translating songs from the Adi Granth certainly involves working not with one language, but several, along with dialectical differences. The languages used by the saints range from Sanskrit; regional Prakrits; western, eastern and southern Apabhramsa; and Sahiskriti. More particularly, we find sant bhasha, Marathi, Old Hindi, central and Lehndi Panjabi, Sgettland Persian. There are also many dialects deployed, such as Purbi Marwari, Bangru, Dakhni, Malwai, and Awadhi." - Shapiro, Michael C.; Dass, Nirmal (2002). "Songs of the Saints, from the Adi Granth". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 122 (4): 924–929. doi:10.2307/3217680.

- Parrinder, Geoffrey (1971). World Religions: From Ancient History to the Present. United States: Hamlyn. p. 256. ISBN 978-0-87196-129-7.

- Torkel Brekke (2014), Religion, War, and Ethics: A Sourcebook of Textual Traditions (Editors: Gregory M. Reichberg and Henrik Syse), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521450386, pages 673, 675, 672-686

- Christopher Shackle and Arvind Mandair (2005), Teachings of the Sikh Gurus, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415266048, pages xxxiv-xli

- William Owen Cole and Piara Singh Sambhi (1995), The Sikhs: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices, Sussex Academic Press, ISBN 978-1898723134, pages 40, 157

- William Owen Cole and Piara Singh Sambhi (1995), The Sikhs: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices, Sussex Academic Press, ISBN 978-1898723134, page 44

- Torkel Brekke (2014), Religion, War, and Ethics: A Sourcebook of Textual Traditions (Editors: Gregory M. Reichberg and Henrik Syse), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521450386, page 675

- Singh, Khushwant (1991). A History of the Sikhs: Vol. 1. 1469-1839. Oxford University Press. p. 46.

- Singh, Khushwant (1991). A History of the Sikhs: Vol. 1. 1469-1839. Oxford University Press. p. 50.

- Gurinder Singh Mann (2001). The Making of Sikh Scripture. Oxford University Press. pp. 33–36. ISBN 978-0-19-513024-9.

- Singh, Khushwant (1991). A History of the Sikhs: Vol. 1. 1469-1839. Oxford University Press. pp. 57–58, 294–295. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- Trumpp, Ernest (2004) [1877]. The Ādi Granth or the Holy Scriptures of the Sikhs. India: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers. p. 1xxxi. ISBN 978-81-215-0244-3.

- Singh, Khushwant (1991). A History of the Sikhs: Vol. 1. 1469-1839. Oxford University Press. pp. 57–61.

- Pashaura Singh; Louis E. Fenech (2014). The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. Oxford University Press. pp. 127–129. ISBN 978-0-19-969930-8.

- Gurinder Singh Mann (2001). The Making of Sikh Scripture. Oxford University Press. pp. 36–38. ISBN 978-0-19-513024-9.

- "Guru Arjan's Rāmakalī Hymn: The Central Issue in the Kartarpur-Banno Debate". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 116 (4): 724–729. 1996. JSTOR 605443.

- W.H. McLeod (1979), The Sikh scriptures: Some Issues, in Sikh Studies: Comparative Perspectives on a Changing Tradition by Mark Jurgensmeyer and N Gerald Barrier (editors), University of California Press, Berkeley Religious Studies Series and Theological Union, pages 101–103

- G.B. Singh (1944), Sri Guru Granth Sahib dian Prachin Biran, Modern Publishers Lahore, (Original (Gurmukhi script); For discussion in English, see Chapter 22 of G Kumar

- William Owen Cole and Piara Singh Sambhi (1995), The Sikhs: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices, Sussex Academic Press, ISBN 978-1898723134, pages 45-46

- Singh, Khushwant (1991). A History of the Sikhs: Vol. 1. 1469-1839. Oxford University Press. pp. 93–94.

- Pashaura Singh; Louis E. Fenech (2014). The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. Oxford University Press. pp. 129–130. ISBN 978-0-19-969930-8.

- McLeod, W. H. (1990). Textual Sources for the Study of Sikhism. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226560854. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- Christopher Shackle; Arvind Mandair (2013). Teachings of the Sikh Gurus: Selections from the Sikh Scriptures. Routledge. pp. xvii–xix. ISBN 978-1-136-45108-9.

- Christopher Shackle; Arvind Mandair (2013). Teachings of the Sikh Gurus: Selections from the Sikh Scriptures. Routledge. pp. xv–xix, xli, 149–158. ISBN 978-1-136-45108-9.

- Pashaura Singh; Louis E. Fenech (2014). The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. Oxford University Press. pp. 125–128. ISBN 978-0-19-969930-8.;

For a more comprehensive discussion of these theories and evidence, see: Pashaura Singh (2003). The Guru Granth Sahib: Canon, Meaning and Authority. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-908773-0. - Pashaura Singh; Louis E. Fenech (2014). The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. Oxford University Press. pp. 127–129. ISBN 978-0-19-969930-8.

- Hoiberg, Dale; Indu Ramchandani (2000). Students' Britannica India. Popular Prakashan. p. 207. ISBN 0-85229-760-2.

- Gupta, Hari Ram (2000). History of the Sikhs Vol. 1; The Sikh Gurus, 1469-1708. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers (P) Ltd. p. 114. ISBN 81-215-0276-4.

- Mann, Gurinder Singh (2001). The making of Sikh Scripture. Oxford University Press. p. 5. ISBN 0-19-513024-3.

- Giriraj, Ruhel (2003). Glory Of Indian Culture. Diamond. p. 96. ISBN 9788171825929.

- The Concise Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, Volume 2. Routledge. 2013. p. 935. ISBN 9781136096020.

- Amrita, Priyamvada (2007). Encyclopaedia of Indian music. p. 252. ISBN 9788126131143.

- Singh, Gurbachan; Sondeep Shankar (1998). The Sikhs : Faith, Philosophy and Folks. Roli & Janssen. p. 55. ISBN 81-7436-037-9.

- Pashaura Singh (2000). The Guru Granth Sahib: Canon, Meaning and Authority. Oxford University Press. pp. 271–275. ISBN 978-0-19-564894-2.

- Gurucharan Singh Anand (2011), Ram Rai, Encyclopedia of Sikhism, Editor in Chief: Harbans Singh, Punjab University

- Louis E. Fenech; W. H. McLeod (2014). Historical Dictionary of Sikhism. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 260–261. ISBN 978-1-4422-3601-1.

- Fowler, Jeaneane (1997). World Religions:An Introduction for Students. Sussex Academic Press. pp. 354–357. ISBN 1-898723-48-6.

- Pashaura Singh (2000). The Guru Granth Sahib: Canon, Meaning and Authority. Oxford University Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-19-564894-2.

- Singh, Nikky-Guninder Kaur (2011). Sikhism: An Introduction. I. B. Tauris. pp. 81–82. ISBN 978-0-85771-962-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kristina Myrvold (2016). The Death of Sacred Texts: Ritual Disposal and Renovation of Texts in World Religions. Routledge. pp. 125–144. ISBN 978-1-317-03640-1.

- W. Owen Cole; Piara Singh Sambhi (2005). A Popular Dictionary of Sikhism: Sikh Religion and Philosophy. Routledge. pp. 38, 79. ISBN 978-1-135-79760-7.

- The Adi Granth, Ernest Trumpp (1877), WH Allen & Co., London; Notes: In this 876 pages publication, Trumpp's translation starts at page 156, while philological notes on the language of the Sikh scripture start at page 140

- Trilochan Singh (1994). Ernest Trumpp and W.H. McLeod as scholars of Sikh history religion and culture. International Centre of Sikh Studies. pp. xv–xvii, 45–49.

- W.H. McLeod (1993). John Stratton Hawley and Gurinder Singh Mann (ed.). Studying the Sikhs: Issues for North America. State University of New York Press. pp. 16–17, 67 note 25. ISBN 978-0-7914-1426-2.

- Nikky-Guninder Kaur Singh (22 February 2011). Sikhism: An Introduction. I.B.Tauris. pp. 128–. ISBN 978-0-85773-549-2.

- Mark Juergensmeyer (1993). John Stratton Hawley and Gurinder Singh Mann (ed.). Studying the Sikhs: Issues for North America. State University of New York Press. pp. 16–17. ISBN 978-0-7914-1426-2.

- Akshaya Kumar (2014). Poetry, Politics and Culture: Essays on Indian Texts and Contexts. Routledge. pp. 167–168. ISBN 978-1-317-80963-0.

- Arvind-Pal Singh Mandair (2013). Sikhism: A Guide for the Perplexed. Bloomsburg Academic. pp. 86–87. ISBN 978-1-4411-0231-7.

- TN Madan (1994). Martin Marty and R Scott Appleby (ed.). Fundamentalisms Observed. University of Chicago Press. pp. 604–610. ISBN 978-0-226-50878-8.

- Donald Dawe (2011), Macauliffe, Max Arthur, Encyclopedia of Sikhism, Volume III, Harbans Singh (Editor), Punjabi University, Patiala;

The translation of Guru Nanak's Janamsakhi and his hymns in the Guru Granth Sahib are in Macauliffe's Volume I, The Sikh Religion (1909) - JS Grewal (1993). John Stratton Hawley; Gurinder Singh Mann (eds.). Studying the Sikhs: Issues for North America. SUNY Press. pp. 164–165. ISBN 978-0-7914-1425-5.

- Arvind-Pal Singh Mandair (2013). Sikhism: A Guide for the Perplexed. A&C Black. pp. 85–89. ISBN 978-1-4411-0231-7.

- Jones, Kenneth W. (1973). "Ham Hindū Nahīn: Arya Sikh Relations, 1877–1905". The Journal of Asian Studies. Cambridge University Press. 32 (3): 457–475. doi:10.2307/2052684.

- Giorgio Shani (2007). Sikh Nationalism and Identity in a Global Age. Routledge. pp. 30–31. ISBN 978-1-134-10189-4.

- Christopher Shackle (2005). Lynne Long (ed.). Translation and Religion. Multilingual Matters. pp. 50–51. ISBN 978-1-84769-550-5.

- Guru Granth Sahib ॥ ੫ ॥, Pages 1-2 of 1430, srigranth.org

- The Adi Granth, Ernest Trumpp (1877), WH Allen & Co, pages 2–5 (see footnotes for alternates)

- The Sikh Religion Vol. 1, Max Authur Macauliffe (1909), Clarendon Press, pages 196–197 (see footnotes for alternates)

- Jolly, Asit (3 April 2004). "Sikh holy book flown to Canada". BBC News. Retrieved 5 January 2010.

- Publishers barred from bringing out Guru Granth Sahib, Varinder Walia, Tribune India, April 23, 2006, Chandigarh

- Modern eco-friendly printing press to print Guru Granth Sahib at Gurudwara Rakabganj: DSGMC, United News of India (July 28, 2019)

- Eleanor Nesbitt, "Sikhism: a very short introduction", ISBN 0-19-280601-7, Oxford University Press, pp. 40-41

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Guru Granth Sahib |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Guru Granth Sahib. |