Women in space

The first woman in space, Soviet cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova, flew in 1963. However space flight programs did not include women after her until the 1980s. Since then many women from a range of countries have worked in space, though overall women are still significantly less often chosen then men to go to space. The first woman to go to the Moon is planned for 2024, as part of the Artemis program.[3]

.jpg)

Three countries maintain active space programs that have included women: China, Russia, and the United States. In addition, a number of other countries — Canada, France, India, Iran, Italy, Japan, South Korea, and the United Kingdom — have sent women into orbit or space on Russian or US missions. Most women in space have been United States citizens, with missions on the Space Shuttle and on the International Space Station.

Women in space face many of the same challenges faced by men: physical difficulties posed by non-Earth conditions and psychological stresses of isolation and separation. Scientific studies on female amphibians and non-human mammals generally show no adverse effect from short space missions.

Women in space programs

Although the first woman flew into space in 1963, very early in crewed space exploration, it would not be until almost 20 years later that another flew.

And while a number of American women successfully underwent the astronaut selection process in the early 1960s they were not eligible to be astronauts: all astronauts were required to be military test pilots, a career not available to women at the time.[4]

NASA opened the space program to female applicants in 1978, in response to the new anti-discrimination laws of the time. When Sally Ride became the first female U.S. astronaut to go into space, the press asked her questions about her reproductive organs and whether she would cry if things went wrong on the job.[5]

Women with children also face questions about how they would compare to traditional expectations of motherhood.[6] Shannon Lucid, one of the first group of female US astronauts, remembers questions by the press on how her children would handle her being a mother in space.[7] Women are often expected to be the ones mainly responsible for child-rearing, which can impact their career.[8]

Soviet Union and Russia

The first woman in space was a Soviet cosmonaut. Valentina Tereshkova launched with the Vostok 6 mission on June 16, 1963.

The second woman overall to go into space was also a cosmonaut: Svetlana Savitskaya in 1982 on the Soyuz T-7 mission. Savitskaya became the first woman to fly to space twice on the Soyuz T-12 mission on July 25, 1984, and the first woman to walk in space when she performed extravehicular activity (EVA) outside the Salyut 7 space station on the Soyuz T-12 mission.[9]

Post-Soviet Russia

Russian Yelena V. Kondakova became the first woman to travel for both the Soyuz programme and on the Space Shuttle. Yelena Serova became the first female Russian cosmonaut to visit the International Space Station on September 26, 2014.[10]

In 2020 Roscosmos announced selection of Anna Kikina, Russia’s only woman cosmonaut for space flight to ISS in 2022. Anna Kikina was admitted to the Russian cosmonaut corps in 2012.[11]

The Russian space program has also hosted international cosmonauts. Helen Sharman from the United Kingdom (1991), Claudie Haigneré from France (1996 and 2001), Anousheh Ansari from Iran (2006), Yi So-yeon of South Korea (2008) and Samantha Cristoforetti from Italy (2014).

United States

The United States did not have a woman in space until 1983, when astronaut Sally Ride launched with the seventh Space Shuttle mission. Since then more than 40 American women have entered space. Most served on the various Space Shuttle flights from 1983 to 2011.

Sally Ride was the third woman overall to go into space.[9] Ride served on the STS-7 from June 18 to 24 in 1983.[9] Judith Resnik was the second American woman in space and the fourth woman overall in space, as a mission specialist on the maiden voyage of Discovery, from August to September 1984,[12] dying less than a year and a half later when the Space Shuttle Challenger was destroyed.

The first US woman to go on an EVA was Kathryn ("Kathy") Sullivan on the STS-41-G, which launched on October 11, 1984.[9] Mae Jemison became the first woman of color in space in 1992. The first woman to pilot the Space Shuttle was Eileen Collins who piloted Discovery on STS-63 (in 1995) and Atlantis on STS-84, and became the first female Shuttle commander on STS-93.

The first woman to be on an ISS expedition crew was Susan Helms on Expedition 2, which lasted from March 2001 until August 2001.[9] United States NASA astronaut Kathleen Rubins became the 60th woman to fly in space when she launched to the International Space Station on July 6, 2016, serving as a flight engineer on Expedition 48 and Expedition 49.[13] She returned in October 2016, having spent 12 hours and 46 minutes on EVA and 115 days, 12 hours and 46 minutes in space as part of these missions.[14] During her stay on ISS she also conducted numerous experiments including some in the area of biology.[14] She was the first person to sequence DNA in space.[15]

In addition to US citizens, US rockets have launched international astronauts. Roberta Bondar (in 1992) and Julie Payette (in 1999 and 2009) from Canada, Kalpana Chawla of India (1997 and 2003), and Chiaki Mukai (in 1994 and 1998) and Naoko Yamazaki (in 2010) of Japan flew as part of the US space program.

A number of other high-profile women have contributed to interest in space programs. In the early 2000s, Lori Garver initiated a project to increase the visibility and viability of commercial spaceflight with the "AstroMom" project. She aimed to fill an unused Soyuz seat bound for the International Space Station because "…creating a spacefaring civilization was one of the most important things we could do in our lifetime.”[16]

On October 18, 2019, the first all female spacewalk was conducted by Jessica Meir and Christina Koch.

NASA's program Artemis aims to send woman to the moon by 2024.

Canada

Roberta Bondar was the first Canadian woman in space, and the second Canadian. She flew on the Space Shuttle Discovery in January 1992.[17]

Another Canadian woman astronaut is Julie Payette from Montreal. Payette was part of the crew of STS-96, on the Space Shuttle Discovery from May 27 to June 6, 1999. During the mission, the crew performed the first manual docking of the Shuttle to the International Space Station, and delivered four tons of logistics and supplies to the station. On Endeavour in 2009 for STS-127, Payette served as a mission specialist. Her main responsibility was to operate the Canadarm robotic arm from the space station.[18] Payette was sworn in as the 29th Governor-General of Canada on October 2, 2017.

Japan

In 1985, Chiaki Mukai was selected as one of three Japanese Payload Specialist candidates for the First Material Processing Test (Spacelab-J) that flew aboard STS-47 in 1992. She also served as a back-up payload specialist for the Neurolab (STS-90) mission. Mukai has logged over 566 hours in space. She flew aboard STS-65 in 1994 and STS-95 in 1998. She is the first Japanese woman to fly in space, and the first Japanese citizen to fly twice.[19]

Naoko Yamazaki became the second Japanese woman to fly into space with her launch on April 5, 2010. Yamazaki entered space on the shuttle Discovery as part of mission STS-131. She returned to Earth on April 20, 2010.[20][21][22][23] Yamazaki worked on ISS hardware development projects in the 1990s. She is an aerospace engineer and also holds a master's degree in that field.[24] She was selected for astronaut training in 1999 and was certified by 2001.[24] She was a mission specialist on her 2010 space shuttle flight, and spent 362 hours in space.[24] Yamazaki worked on robotics and transitioned through the reorganization of Japanese spaceflight organization in 2003 when NASDA (National Space Development Agency) merged with ISAS (Institute of Space and Astronautical Science) and NAL (National Aerospace Laboratory of Japan).[24] The new organization was called JAXA (Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency).[24]

China

In 2012, the Chinese space program sent their first woman to space.

China's first female astronaut candidates, chosen in 2010 from the ranks of fighter pilots, were required to be married mothers.[25] The Chinese stated that married women were "more physically and psychologically mature" and that the rule that they had have had children was because of concerns that spaceflight would harm their reproductive organs (including unreleased ova).[25] The unknown nature of the effects of spaceflight on women was also noted.[25] However, the director of the China Astronaut Centre has stated that marriage is a preference but not a strict limitation.[26] Part of why they were so strict was because it was their first astronaut selection and they were trying be "extra cautious".[25] China's first woman astronaut, Liu Yang, was married but had no children at the time of her flight in June 2012.[27][28]

First women in space of other countries

- Helen Sharman, United Kingdom (1991, first western European woman in space)

- Claudie Haigneré, France (1996)

- Jessica Meir, Sweden (2019, due to dual citizenship, though flown as US astronaut)

- Yi So-yeon, South Korea (2008)

- Samantha Cristoforetti, Italy (2014)

Women space tourists

Anousheh Ansari was the fourth overall self-funded space traveler, and the first self-funded woman to fly to the International Space Station. She flew to the station in 2006 on the Soyuz TMA-9 spacecraft.[29] Her mission launched from the Baikonur Cosmodrome on September 18, 2006 at 08:09 MSD (04:09 UTC), docked with the ISS at 09:21 MSD (05:21 UTC) on 20 September, and returned to Earth on April 21, 2007. Soyuz TMA-9 transported two-thirds of ISS Expedition 14 to the space station along with Ansari.[30] Ansari performed several experiments on behalf of the European Space Agency.[30]

By 2015 four women were classified as "space flight participants": Helen Sharman, Claudie Haigneré (born André-Deshays), Anousheh Ansari, and Yi So-yeon.[9]

Fatalities

Payload Specialist Christa McAuliffe and mission specialist Judith Resnik became the first women to die on a space mission when the Space Shuttle Challenger exploded less than 2 minutes after launch with the loss of all hands.[31][32][33][34][35]

In the 2003 Space Shuttle Columbia disaster the crew was lost on re-entry, including mission specialists Kalpana Chawla and Laurel Clark.[36]

Physical effects of space on women

Female astronauts are subject to the same general physical effects of space travel as men. These include physiological changes due to weightlessness such as loss of bone and muscle mass, health threats from cosmic rays, dangers due to vacuum and temperature, and psychological stress.

NASA reports initially argued that menstruation could pose serious health risks or have a negative effect on performance, although it is now dealt with as a matter of routine.[37][38]

Astronaut clothing for men has been based on technology used to make bras, and since women have been sent to space the previously men focused clothing has been reconsidered addressing the issues and needs for clothing like space suits for extravehicular activity (EVA) and bras, e.g. for exercise in micro-g environments.[39] Low number of produced smaller sized space suits has been hindering women astronauts to do EVAs because of a lack of fitting suits.[39]

Radiation and uterine and breast cancer

Both men and women are affected by radiation. Massive particles are a concern for astronauts outside the earth's magnetic field who receive solar particles from solar proton events (SPE) and galactic cosmic rays from cosmic sources. These high-energy charged nuclei are blocked by Earth's magnetic field but pose a major health concern for astronauts traveling to the moon and to any distant location beyond the earth orbit. Evidence indicates past solar particle event (SPE) radiation levels that would have been lethal for unprotected astronauts.[44]

However, due to the currently used risk models for endometrial, ovarian and breast cancer, women at NASA can currently only spend half as much time on missions as men, which limits their career options compared to men.[45]

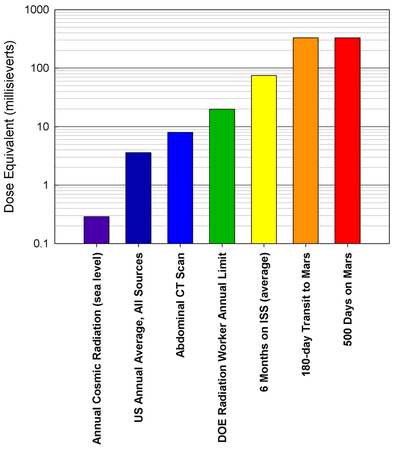

German standards for pregnant woman set a limit of 50 mSv/year for the gonads (ovaries) and uterus, and 150 mSv/year for the breasts.[46] Astronauts on Apollo and Skylab missions received on average 1.2 mSv/day and 1.4 mSv/day respectively.[47] Exposures on the ISS average 0.4 mSv per day[47] (150 mSv per year), although frequent crew rotations minimize risk to individuals.[48] A trip to Mars with current technology might be related to measurements by the Mars Science Laboratory which for a 180-day journey estimated an exposure approximately 300 mSv, which would be equivalent of 24 CAT scans or "15 times an annual radiation limit for a worker in a nuclear power plant".[49]

Fertility

A study published in 2005 in the International Journal of Impotence Research reported that short-duration missions (no longer than nine days) did not affect "the ability of astronauts to conceive and bear healthy children to term."[25] In another experiment, the frog Xenopus laevis successfully ovulated in space.[50]

Pregnancy

NASA has not permitted pregnant astronauts to fly in space,[51] and there have been no pregnant women in space.[52] However, various science experiments have dealt with some aspects of pregnancy.[52]

For air travel, the United States' Federal Aviation Administration recommends a limit of 1 mSv total for a pregnancy, and no more than 0.5 mSv per month.[53]

For fetus radiation increases the risk of childhood cancers.[54] Additionally children of female astronauts could be sterile if the astronaut were exposed to too much ionizing radiation during the later stages of a pregnancy.[55] Ionizing radiation may destroy the egg cells of a female fetus inside a pregnant woman, rendering the offspring infertile even when grown.[55]

While no human had gestated in space as of 2003, scientists have conducted experiments on non-human mammalian gestation.[56] Space missions that have studied "reproducing and growing mammals" include Kosmos 1129 and 1154, as the Shuttle missions STS-66, 70, 72, and 90.[57] A Soviet experiment in 1983 showed that a rat that orbited while pregnant later gave birth to healthy babies; the babies were "thinner and weaker than their Earth-based counterparts and lagged behind a bit in their mental development," although the developing pups eventually caught up.[52]

The lack of knowledge about pregnancy and birth control in micro-gravity has been noted in regards to conducting long-term space missions.[51]

Post-natal

A 1998 Space Shuttle mission showed that rodent Rattus mothers were either not producing enough milk or not feeding their offspring in space.[58] However, a later study on pregnant rats showed that the animals successfully gave birth and lactated normally.[52]

To date no human children have been born in space; neither have children gone into space.[52] Nevertheless, the idea of children in space is taken seriously enough that some have discussed how to write curriculum for children in space-colonizing families.[59]

See also

- List of female astronauts

- List of spaceflight records

- List of space travelers by nationality

- Maximum Absorbency Garment (NASA garment to help contain bodily emissions during spaceflight for men and women)

- Mercury 13

- List of women astronomers

- Women in science

- List of female explorers and travelers

References

- "Four Women will Fly in Space for the First Time in the History". Russian Federal Space Agency. 3 April 2010. Archived from the original on 8 April 2010. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- "Women in Space". NASA. Retrieved 12 April 2010.

- "NASA: Moon to Mars". NASA. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- Weitekamp, Margaret A.; Garber, Steve. "Lovelace's Woman in Space Program". NASA.

- Ryan, Michael. "A Ride in Space – NASA, Sally Ride". People. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- "Astronaut Mom Karen Nyberg Prepares for Mission and Motherhood 255 Miles Up". International Space Station. NASA. May 9, 2013.

- Foster, Amy E. (December 2011). Integrating Women Into the Astronaut Corps: Politics and Logistics at NASA, 1972-2004. Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 146. ISBN 978-1-4214-0195-9.

- Kramer, A. (July 2, 2013). "Parenting From Earth's Orbit". The New York Times.

- Garber, Stephen (July 2017) [July 6, 2015]. "Women in Space". NASA History Program Office. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

- "First Russian woman in International Space Station mission". BBC News. 26 September 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- "Russia's only female cosmonaut expected to make spaceflight in autumn of 2022". TASS. 27 June 2020. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- Wade, Mark. "Resnik". Archived from the original on 2009-10-08. Retrieved 2009-11-21.

- "Station-Bound NASA Astronaut is the 60th Woman to Fly into Space". SPACE.com. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- Dunbar, Brian (December 5, 2016). Whiting, Melanie (ed.). "Kathleen "Kate" Rubins (PH.D.) NASA Astronaut". NASA. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved January 7, 2016.

- Robbins, Gary (August 29, 2016). "UCSD alumna first to sequence DNA in space". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved October 26, 2016.

- Foust, Jeff (November 19, 2007). "AstroMom and Basstronaut, revisited". The Space Review.

- "Dr. Roberta Lynn Bondar: Canada's First Female Astronaut". Sault History Online. Sault Ste. Marie Public Library. 2008. Retrieved 2011-04-17.

- "Inventive Women Biographies: Julie Payette". Inventive Women. Inventive Women Inc. 2006. Archived from the original on February 17, 2009.

- "Astronaut Bio: Chiaki Mukai". NASA. October 2003.

- Harwood, William. "Shuttle Lifts Off for Space Station", The New York Times, New York City, April 5, 2010. Retrieved on 2010-04-05.

- "Astronaut set to become Japan's first mum in space". Reuters UK. Reuters. November 11, 2008. Retrieved November 18, 2008.

- JAXA (November 11, 2008). "Naoko Yamazaki to become second Japanese female astronaut to fly to space". Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency. Archived from the original on December 13, 2009. Retrieved 2008-11-18.

- NASA (2008). "Consolidated Launch Manifest". NASA. Retrieved October 25, 2008.

- "Naoko Yamazaki, JAXA Astronaut". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. April 2010. Archived from the original on July 26, 2015. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- Brenhouse, Hillary (March 25, 2010). "China: Female Astronauts Must Be Married with Children". TIME.

- "Exclusive interview: Astronauts selection process". CCTV News. CNTV. June 16, 2012. Archived from the original on December 13, 2014. Retrieved June 17, 2012.

- 孙兰兰 贾磊 (2012-06-13). "女航天员刘洋婆婆:希望媳妇能尽快生个孩子_资讯频道_凤凰网" [Mother-in-law of female astronaut Liu Yang: I hope daughter-in-law gives birth to a child as soon as possible]. News.ifeng.com. Retrieved 2012-06-18.

- Amos, Jonathan (June 16, 2012). "China launches space mission with first woman astronaut". BBC. Retrieved June 16, 2012.

- Ansari, Anousheh; Hickam, Homer (March 2, 2010). My Dream of Stars: From Daughter of Iran to Space Pioneer. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 9780230105799. Archived from the original on March 9, 2014. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- "ESA experiments with spaceflight participant Ansari to ISS". International Space Center. European Space Agency. 12 September 2006. Retrieved 2006-09-22.

- Lathers, Marie (2010). Space Oddities: Women and Outer Space in Popular Film and Culture, 1960-2000. The Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 106. ISBN 978-1-4411-9049-9.

- Corrigan, Grace George (2000). A Journal for Christa: Christa McAuliffe, Teacher in Space. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. p. 123. ISBN 9780803264113.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "The Crew of the Challenger Shuttle Mission in 1986". NASA. 2004-10-22.

- Corrigan 2000, p. 40

- Burgess, Colin; Corrigan, Grace George (2000). Teacher in space: Christa McAuliffe and the Challenger legacy. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-6182-2.

- "Reflections on the Loss of STS-107, the Space Shuttle Columbia: Ten Years Ago". February 2013.

- Teitel, Amy Shira (June 10, 2016). "A Brief History Of Menstruating In Space: Before women started flying in space, NASA was a little worried they might die having their periods". Popular Science. Bonnier Corporation. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- Beck, Julie (April 21, 2016). "Women Astronauts: To Menstruate or Not to Menstruate". The Atlantic. Retrieved January 7, 2016.

- Sokolowski, Susan L. (5 April 2019). "Female astronauts: How performance products like space suits and bras are designed to pave the way for women's accomplishments". The Conversation. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- Kerr, Richard (31 May 2013). "Radiation Will Make Astronauts' Trip to Mars Even Riskier". Science. 340 (6136): 1031. Bibcode:2013Sci...340.1031K. doi:10.1126/science.340.6136.1031. PMID 23723213.

- Zeitlin, C.; et al. (31 May 2013). "Measurements of Energetic Particle Radiation in Transit to Mars on the Mars Science Laboratory" (PDF). Science. 340 (6136): 1080–1084. Bibcode:2013Sci...340.1080Z. doi:10.1126/science.1235989. PMID 23723233.

- Chang, Kenneth (30 May 2013). "Data Point to Radiation Risk for Travelers to Mars". New York Times. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- Gelling, Cristy (June 29, 2013). "Mars trip would deliver big radiation dose; Curiosity instrument confirms expectation of major exposures". Science News. 183 (13): 8. doi:10.1002/scin.5591831304. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- Battersby, Stephen (21 March 2005). "Superflares could kill unprotected astronauts". New Scientist. Reed Business Information Ltd.

- Kramer, Miriam (August 27, 2013). "Female Astronauts Face Discrimination from Space Radiation Concerns, Astronauts Say". Space.com. Purch. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- Koelzer, Winfried (January 2011). "Radiation exposure, dose limits, Germany". Glossary of nuclear terms. European Nuclear Society. Archived from the original on November 13, 2016. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- Cucinotta, Francis A., "Table-4. Average dose (D) or dose-rate recorded by dosimetry badge and estimates of the effective doses, E received by crews in NASA programs through 2004" (PDF), Space Radiation Organ Doses for Astronauts on Past and Future Missions, p. 22, retrieved 1 February 2014

- W., Anderson, Rupert. The cosmic compendium : space medicine. [printer not identified]. [Place of publication not identified]. ISBN 9781329052000. OCLC 935213314.

- Gifford, Sheyna E. (February 18, 2014). "Calculated Risks: How Radiation Rules Manned Mars Exploration". Astrobiology Magazine. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- Ronca, p. 218.

- Foster, p. 139.

- Stierwalt, Sabrina (May 2006). "Can a human give birth in space?". Ask an Astronomer. Cornell University.

- Davis, Jeffrey R.; Johnson, Robert; Stepanek, Jan; Fogarty, Jennifer A., eds. (2008). Fundamentals of Aerospace Medicine (Fourth ed.). pp. 221–230. ISBN 9780781774666. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- Radiology Clinician Fact Sheet: Radiation Information (PDF), NSW Agency for Clinical Innovation, September 2012, retrieved January 7, 2017

- Taylor, Jerome (February 14, 2011). "Why infertility will stop humans colonising space". The Independent.

- Ronca, April E. (July 15, 2003), "Mammalian Development in Space", in Cogoli, Augusto (ed.), Advances in Space Biology and Medicine, 9, Elsevier Science B.V., p. 219, ISBN 978-0-444-51353-3

- Ronca, p. 222.

- "Nasa To Probe The Deaths Of 51 Baby Rats In Space". Chicago Tribune. April 29, 1998.

- Britton, Alan (2010-11-04), "A school curriculum for the children of stace settlers", in Landfester, Ulrike; Remuss, Nina-Louisa; Schrogl, Kai-Uwe; Worms, Jean-Claude (eds.), Humans in Outer Space: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, p. 65, ISBN 9783709102800

External links

- Women in Space from Telegraph Jobs

- 50 years of humans in space: European Women in Space (ESA)