Women in Mali

The status and social roles of women in Mali have been formed by the complex interplay of a variety of traditions in ethnic communities, the rise and fall of the great Sahelien states, French colonial rule, independence, urbanisation, and postcolonial conflict and progress. Forming just less than half Mali's population, Malian women have sometimes been the center of matrilineal societies, but have always been crucial to the economic and social structure of this largely rural, agricultural society.

A Fula girl in Mali | |

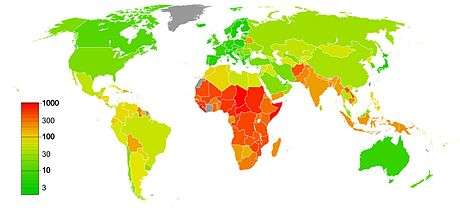

| Gender Inequality Index | |

|---|---|

| Value | 0.649 (2012) |

| Rank | 141st |

| Maternal mortality (per 100,000) | 540 (2010) |

| Women in parliament | 10.2% (2012) |

| Females over 25 with secondary education | 11.3% (2010) |

| Women in labour force | 63% (2017)[1] |

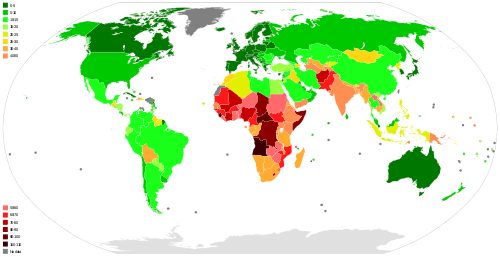

| Global Gender Gap Index[2] | |

| Value | 0.582 (2018) |

| Rank | 143rd out of 149 |

Their role, too, has been shaped by the conflicts over religion, as animist societies gave way gradually to Islam in the 1100–1900 period. In recent years, the rise of religious fundamentalism has posed a thereat to women's wellbeing.[3]

Contemporary problems faced by women in Mali include high rate of violence against women,[4] child marriage[5] and female genital mutilation.[6]

Cultural background

Mali is a landlocked country in West Africa. It obtained independence from France in 1960. The Northern Mali conflict has destabilized the country. Mali has more than 18 million inhabitants, and it is ethically diverse being formed of the following groups: Bambara 34.1%, Fulani (Peul) 14.7%, Sarakole 10.8%, Senufo 10.5%, Dogon 8.9%, Malinke 8.7%, Bobo 2.9%, Songhai 1.6%, Tuareg 0.9%, other Malian 6.1%, from member of Economic Community of West African States 0.3%, other 0.4%. The vast majority of the population follows Islam. The urbanization is 42.4%. The fertility rate is almost 6 children born/woman, one of the highest in the world.[7]

Education

Education is compulsory from ages six to 15. However, many children do not attend school, and girls' enrollment is lower than that of boys at all levels due to factors such as poverty, societal preference to educate boys, child marriage and sexual harassment.[8] Women's literacy rate (aged 15 and over) is significantly lower than that of men: female 22.2%, compared to male 45.1% (2015 est.). [9]

Health care

Mali is one of the world’s poorest nations and is severely affected by poor health and sanitation. Women's health is negatively impacted, although the government provides subsidised medical care to children as well as adults of both sexes. The Constitution of Mali guarantees the right to health.[10] The healthcare policy is based on community involvement, cost recovery and the availability of essential medicines, and it is developed by the Ministry of Health and implemented by the National Health Directorate.[11] In Mali, maternal mortality and infant mortality are very high. Early marriage, lack of family planning, very high fertility, and female genital mutilation contribute to women's illhealth.

Marriage

Child marriage is common in Mali, fueled by lax laws, and lack of enforcement of even the existing laws. The minimum age to marry without parental consent is 16 for girls and 18 for boys. A 15-year-old girl may marry with parental consent if a civil judge approves.[12]

A Malian NGO reported that at least 10 girls-—some below the age of 13—-lost their lives between 2005 and May 2007 because of medical complications resulting from early marriage. In Mali, about 75% of girls up to age 14 and 89% of women age 15-49 are estimated to have undergone female genital mutilation (FGM), a practice which endangers their health.[13]

Family law

Women do not have equal status and rights, particularly concerning divorce and inheritance. The law allows polygamy. Women are legally obligated to obey their husbands and are particularly vulnerable in cases of divorce, child custody, and inheritance. Even the limited rights that women have are often unenforced, due to lack of education and information, as well as cultural views which consider women as inferior. According to the law, the Ministry for the Promotion of Women, the Family, and Children is responsible for ensuring the legal rights of women.[14]

Rights of women under law

Article 2 of the Constitution of Mali states that "All Malians are born and live free and equal in their rights and duties. Any discrimination based on social origin, color, language, race, sex, religion, or political opinion is prohibited", while Article 3 states that "No one will be put to torture, nor to inhumane, cruel, degrading, or humiliating treatment".[15]

Abuse and exploitation of girls

Abuse of girls includes child marriage and female genital mutilation. There are no comprehensive government statistics on child abuse, and the problem is widespread. Child abuse is usually unreported. The police and the social services department in the Ministry of Solidarity and Humanitarian Action have investigated and intervened in some reported cases of child abuse or neglect.[16][17]

Child marriage is very prevalent in Mali, with a majority of girls being married before 18.[18] There is a very strong link between child marriage and lack of education, as well as polygamy, with child brides being more likely to be a 2nd, 3rd or 4th wife.[19]

A 2004 governmental study, which involved 450 interviews, found that the children most at risk for sexual exploitation were girls between the ages of 12 and 18 who worked as street vendors or domestic servants, or who were homeless children or the victims of child trafficking. Such exploitation was most prevalent in areas in which the population and economy were in flux, such as border zones or towns on transportation routes or in mining areas. The study noted that most cases of sexual exploitation went unreported and recommended that the country strengthen its laws to protect children.[20]

Female genital mutilation

Female genital mutilation (FGM) is common, particularly in rural areas, and is performed on girls between the ages of six months to six years. About 75% of girls up to age 14 and 89% of women age 15-49 are estimated to have undergone FGM. [21] Girls are often married at age 13-15, so FGM is performed before this age.[22]

The government has launched a two-phase plan to eliminate FGM, originally by 2008. According to the local human rights organisations fighting FGM, the educational phase (workshops, videos, and theatre) continues in cities, and FGM reportedly has decreased substantially among children of educated parents. In many instances, FGM practitioners have agreed to stop the practice in exchange for other income-generating activity.[23] The National Committee Against Violence Towards Women linked all the NGOs combating FGM,[20] and high-profile work by Former Teachers' Union leader Fatoumata Sire Diakite, president of the Association for the Progress and Defense of Women (APDF) have led efforts to educate rural women and community leaders about the danger FGM poses.[24]

Mali has one of the highest rates of FGM in the world, partly due to the fact that there is a very high ongoing support for the practice among the population: only 20% of Malian women and 21% of men think the practice should end.[25]

Rape and violence

The law criminalises rape. The 2011 US Country Report on Human Rights Practices in Mali states that "There is no law specifically prohibiting spousal rape, but law enforcement officials stated the criminal laws against rape apply to spousal rape."[26] Rape is a widespread problem. Most cases are not reported because of societal pressure, particularly due to the fact that the attackers are frequently close relatives and victims fear retaliation.[27] A report concluded that while 300 women came forward to report sexual abuse every year in Bamako alone, in 2007 only two men were convicted of the crime. Malian organisations like Bamako's Women and Law and Development in Africa, led by lawyer Sidibe Djenba Diop, push for education, strengthening laws, and forcing their application.[28]

Domestic violence against women, including spousal abuse, was tolerated and common. Spousal abuse is a crime, but police were reluctant to enforce laws against or intervene in cases of domestic violence. Assault is punishable by prison terms of one to five years and fines of up to $1,000 (465,000 CFA francs) or, if premeditated, up to 10 years' imprisonment. Many women were reluctant to file complaints against their husbands because they were unable to support themselves financially.[29]

The Ministry for the Promotion of Women, Children, and the Family produced a guide on violence against women for use by health care providers, police, lawyers, and judges. The guide provides definitions of the types of violence and guidelines on how each should be handled. NGOs Action for the Defense and Promotion of Women Rights and Action for the Promotion of Household Maids operated shelters.[20]

Sexual harassment occurs routinely , including in schools, without any government efforts to prevent it, and the law does not prohibit it.[30]

Economic rights and access

While the law gives women equal property rights, traditional practice and ignorance of the law prevents women—even educated women—from taking full advantage of their rights. A community property marriage must be specified in the marriage contract. In addition, if the type of marriage was not specified on the marriage certificate, judges presume the marriage was polygynous. While 48% of Malian women are engaged in agriculture, the vast majority may only access land to which men hold the primary rights. While the Constitution and some laws in Mali support equality between men and women, in practice Malian women do not enjoy equal status with men with respect to property rights and inheritance.[31]

Women's access to employment and to economic and educational opportunities is limited. The labor law prohibits discrimination in employment and occupation based on race, gender, religion, political opinion, nationality, or ethnicity; but this is not effectively enforced, and discrimination is common.[32] Most women in Mali work in the informal sector and in agriculture. The government, which is the major formal sector employer, ostensibly pays women the same as men for similar work, but differences in job descriptions result in pay inequality.[33]

Under a 2004–8 national plan of action to promote the status of women, the government continued efforts to reduce inequalities between men and women and to create links between women within the Economic Community of West African States and throughout Africa.[20]

Prostitution and trafficking in persons

Prostitution is legal, but third party activities (procuring) are illegal.[34] Prostitution is common in Malian cities, and has increased due to the armed conflict.[35]

Mali is a source, transit, and destination country for adults and children subjected to forced labor and sex trafficking. Internal trafficking is more common than transnational trafficking. There are also women and girls from other West African countries, particularly Nigeria and Benin, who are exploited in prostitution and sex trafficking in Mali. These women are often recruited with promises of legitimate jobs in Bamako but then exploited in sex trafficking throughout Mali, including in Chinese-run hotels, and especially in small mining communities. There are reports of corruption and complicity among local police and gendarmes.[36]

The legislative framework was strengthened: Law 2012-023 Relating to the Combat against Trafficking in Persons and Similar Practices, as amended, criminalizes forced labor and sex trafficking. The law prescribes penalties of five to 10 years imprisonment for sex and labor trafficking—except forced begging—and separately criminalizes forced begging with lesser penalties of two to five years imprisonment and a fine.[37]

The Ministry of Justice and the Ministry for the Advancement of Women, Children, and the Family have created programs meant to curb such abuses.[38]

Contemporary slavery

In 2008, the Tuareg-based human rights group Temedt, along with Anti-Slavery International, reported that "several thousand" members of the Tuareg Bella caste remain enslaved in the Gao Region and especially around the towns of Menaka and Ansongo. They complain that while laws provide redress, cases are rarely resolved by Malian courts.[39]

Women's pressure groups

Several women's rights groups, such as the Association of Malian Women Lawyers, the Association of Women in Law and Development, the Collective of Women's Associations, and the Association for the Defense of Women's Rights (Association pour le Progres et la Defense des Droits des Femmes Maliennes – APDF), worked to highlight legal inequities, primarily in the family code, through debates, conferences, and women's rights training. These groups also provided legal assistance to women and targeted magistrates, police officers, and religious and traditional leaders in educational outreach to promote women's rights.[20]

Malian women's rights NGOs, such as Action for the Promotion and Development of Women, the Committee for the Defense of Women's Rights, and the Women's and Children's Rights Watch (CADEF),[40] educated local populations about the negative consequences of underage marriage. The government also helped to enable girls married at an early age to continue in school.[20]

Women in politics

A small number of Malian women have reached the highest level of business, academia and government, with women holding several government Ministerial posts and seats in the National Assembly of Mali. Aminata Dramane Traoré, author and political activist has served as the Minister of Culture and Tourism of Mali, coordinator of the United Nations Development Programme, and board member of the International Press Service.

Sidibé Aminata Diallo, a professor at the University of Bamako, is leader of the Movement for Environmental Education and Sustainable Development political party, and in 2007 became the first woman to stand for President of Mali as one of eight candidates in the April 2007 presidential election.[41] Diallo received over 12,000 votes in the election, 0.55% of the total.[42]

References

- https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.TLF.ACTI.FE.ZS

- "The Global Gender Gap Report 2018" (PDF). World Economic Forum. pp. 10–11.

- https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/africa/mali-unmarried-couple-stoned-death-islamic-law-break-militants-al-qaeda-kidal-france-un-advance-a7742221.html

- https://www.news24.com/Africa/News/Rising-violence-against-women-in-Mali-20140620-3

- https://www.girlsnotbrides.org/child-marriage/mali/

- https://www.unicef.org/mali/media_centre_7809.html

- https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ml.html

- United States Department of State

- https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ml.html

- http://www.access2insulin.org/malis-health-system.html

- http://www.access2insulin.org/malis-health-system.html

- United States Department of State

- https://www.unicef.org/mali/media_centre_7809.html

- United States Department of State

- http://confinder.richmond.edu/admin/docs/Mali.pdf

- United States Department of State

- Wing, S. D. , (2002) "Women's Rights in West Africa: Legal Pluralism and Constitutional Law", Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, Boston Marriott Copley Place, Sheraton Boston & Hynes Convention Center, Boston, Massachusetts Online Retrieved 15 September 2008

- https://www.girlsnotbrides.org/child-marriage/mali/

- https://www.girlsnotbrides.org/child-marriage/mali/

- Report on Human Rights Practices 2006: Mali. United States Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor (6 March 2007). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- https://www.unicef.org/mali/media_centre_7809.html

- https://plan-international.org/blog/2016/02/working-communities-stop-fgm-mali

- MALI: Excision practiced where pre-Islamic traditions strongest, IRIN, 28 October 2006.

- The Struggle Against FGM in Mali, United Nations Development Fund for Women, 24 November 2000

- https://plan-international.org/blog/2016/02/working-communities-stop-fgm-mali

- "Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2016". www.state.gov. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- United States Department of State

- MALI: Violence against women on rise, Bamako, 2 October 2008 (IRIN)].

- Violence against Women in Mali, Human Rights Committee. SEVENTY-SEVENTH SESSION– 17 MARCH – 4 APRIL 2003, UN-OMTC

- United States Department of State

- http://www.focusonland.com/fola/en/countries/brief-women-inheritance-and-islam-in-mali/

- United States Department of State

- United States Department of State

- "Droit-Afrique - Portail du droit des 24 pays d'Afrique francophone" (PDF). Droit-Afrique. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- https://www.upi.com/Prostitution-increasing-in-Mali/44841370449159/

- United States Department of State

- United States Department of State

- United States Department of State

- MALI: Thousands still live in slavery in north. IRIN, 14 Jul 2008

- cadef. "le blog cadef". le blog cadef. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- Almahady Cissé, "A Presidential Election That Breaks With Tradition", Inter Press Service (allAfrica.com), 24 April 2007.

- "Présidentielle au Mali: la Cour constitutionnelle valide la réélection de Touré", AFP (Jeuneafrique.com), 12 May 2007 (in French).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Women of Mali. |