Kingdom of Romania

The Kingdom of Romania (Romanian: Regatul României) was a constitutional monarchy that existed in Romania from 14 March(O.S.) / 26 March 1881 with the crowning of prince Karl of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen as King Carol I, until 1947 with the abdication of King Michael I of Romania, and the Romanian parliament proclaiming Romania a people's republic.

Kingdom of Romania Regatul României | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1881–1947 | |||||||||||||||||||||

Flag

Coat of arms

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Motto: Nihil Sine Deo ("Nothing without God") | |||||||||||||||||||||

Anthem: Marș triumfal ("Triumphant March") (1881–1884) Trăiască Regele ("Long live the King") (1884–1947) | |||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png) The Kingdom of Romania in 1939 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Bucharest (1881–1916, 1918–1947) Iași (Jassy) (1916–1918) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Romanian (official)[1] German, and Hungarian | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Romanian Orthodox | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Constitutional monarchy (1881–1937; 1944-1947) Fascist dictatorship (1937–1938) Absolute monarchy (1938–1940) Totalitarian state (1940–1941) Military dictatorship (1941–1944) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||||||||||||

• 1881–1914 | Carol I | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1914–1927 | Ferdinand I | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1927–1930 | Michael I (1st reign) | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1930–1940 | Carol II | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1940–1947 | Michael I (2nd reign) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||||||||||||||

• 1881 | Ion Brătianu (first) | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1940–1944 | Ion Antonescu[a] | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1945–1947 | Petru Groza (last) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Parliament | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Senate | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Assembly of Deputies | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Belle Époque • World War I • Interwar period • World War II | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 14 March 1881 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 August 1913 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 June 1920 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 29 March 1923 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 20 February 1938 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 14 September 1940 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 21 January 1941 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 23 August 1944 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 12 September 1944 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 30 December 1947 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1915[b] | 138,000 km2 (53,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 1940[b][c] | 295,049 km2 (113,919 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||||||

• 1915[b] | 7,900,000 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 20,058,378 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Romanian Leu | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

a. ^ Was formally declared Conducător (literally, "Leader") of the state on 6 September 1940, by a royal decree which consecrated a ceremonial role for the monarch.[2] b. ^ Area and population according to Ioan Suciu, Istoria contemporana a României (1918–2005).[3] c. ^ The indicator for the localities of Romania (1941).[4] | |||||||||||||||||||||

From 1859 to 1877, Romania evolved from a personal union of two vassal principalities (Moldavia and Wallachia) under a single prince to an autonomous principality with a Hohenzollern monarchy. The country gained its independence from the Ottoman Empire during the 1877–1878 Russo-Turkish War (known locally as the Romanian War of Independence), when it also received Northern Dobruja in exchange for the southern part of Bessarabia. The kingdom's territory during the reign of King Carol I, between 14(O.S.) / 26 March 1881 and 27 September(O.S.) / 10 October 1914 is sometimes referred as the Romanian Old Kingdom, to distinguish it from "Greater Romania", which included the provinces that became part of the state after World War I (Bessarabia, Banat, Bukovina, and Transylvania).

With the exception of the southern halves of Bukovina and Transylvania, these territories were ceded to neighboring countries in 1940, under the pressure of Nazi Germany or the Soviet Union. Following a disastrous World War II campaign on the side of the Axis powers and name change (Legionary Romania), Romania joined the Allies in 1944, recovering Northern Transylvania. The influence of the neighboring Soviet Union and the policies followed by Communist-dominated coalition governments ultimately led to the abolition of the monarchy, with Romania becoming a People's Republic on the last day of 1947.

Unification and monarchy

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Romania |

|

|

Post-Revolution |

|

|

The 1859 ascendancy of Alexandru Ioan Cuza as prince of both Moldavia and Wallachia under the nominal[5][6] suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire united an identifiably Romanian nation under a single ruler. On 24 January(O.S.) / 5 February 1862, the two principalities were formally united to form the Principality of Romania, with Bucharest as its capital.

On 11(O.S.) / 23 February 1866 a so-called Monstrous coalition, composed of Conservatives and radical Liberals, forced Cuza to abdicate. The German prince Charles of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen was appointed as Prince of Romania, in a move to assure German backing to unity and future independence. He immediately adopted the Romanian spelling of his name, Carol, and his cognatic descendants would rule Romania until the overthrow of the monarchy in 1947.

Following the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878, Romania was recognized as an independent state by the Treaty of Berlin, 1878 and acquired Dobruja, although it was forced to surrender southern Bessarabia (Budjak) to Russia. On 15 March 1881, as an assertion of full sovereignty, the Romanian parliament raised the country to the status of a kingdom, and Carol was crowned as king on 10 May.

The new state, squeezed between the Ottoman, Austro-Hungarian, and Russian Empires, with Slavic populations on its southwestern, southern, and northeastern borders, the Black Sea due east, and Hungarian neighbors on its western and northwestern borders, looked to the West, particularly France, for its cultural, educational, and administrative models.

Abstaining from the Initial Balkan War against the Ottoman Empire, the Kingdom of Romania entered the Second Balkan War in June 1913 against the Tsardom of Bulgaria. 330,000 Romanian troops moved across the Danube and into Bulgaria. One army occupied Southern Dobrudja and another moved into northern Bulgaria to threaten Sofia, helping to bring an end to the war. Romania thus acquired the ethnically-mixed territory of Southern Dobrudja, which it had desired for years.

In 1916 Romania entered World War I on the Entente side. Romania engaged in a conflict against Bulgaria but as a result Bulgarian forces, after a series of successful battles, regained Dobruja, which had been previously ceded from Bulgaria by the treaty of Bucharest and the Berlin congress. Although the Romanian forces did not fare well militarily, by the end of the war the Austrian and Russian empires were gone; various assemblies proclaimed as representative bodies in Transylvania, Bessarabia and Bukovina decided on union with Romania. In 1919 by the Treaty of Saint-Germain and in 1920 by the Treaty of Trianon most of territories claimed were assigned to Romania.

Romanian Old Kingdom (1881–1918)

The Romanian Old Kingdom (Romanian: Vechiul Regat or just Regat; German: Regat or Altreich) is a colloquial term referring to the territory covered by the first independent Romanian nation state, which was composed of the Danubian Principalities — Wallachia and Moldavia. It was achieved when, under the auspices of the Treaty of Paris (1856), the ad hoc Divans of both countries - which were under Imperial Ottoman suzerainty at the time - voted for Alexander Ioan Cuza as their prince, thus achieving a de facto unification. The region itself is defined by the result of that political act, followed by the inclusion of Northern Dobruja in 1878, the proclamation of the Kingdom of Romania in 1881, and the annexation of Southern Dobruja in 1913.

The term came into use after World War I, when the Old Kingdom was opposed to Greater Romania, which included Transylvania, Banat, Bessarabia, and Bukovina. Nowadays, the term mainly has a historical relevance, and is otherwise used as a common term for all regions in Romania included in both the Old Kingdom and present-day borders (namely: Wallachia, Moldavia, and Northern Dobruja).

Maps

Proclamation Act of the Kingdom of Romania

Proclamation Act of the Kingdom of Romania.svg.png) The Kingdom of Romania in 1890

The Kingdom of Romania in 1890- 1901 German map of Romania

.svg.png) The Kingdom of Romania in 1914

The Kingdom of Romania in 1914

World War I

Romania delayed in entering World War I, but ultimately declared war on the Central Powers in 1916. The Romanian military campaign ended in stalemate when the Central Powers quickly crushed the country's offensive into Transylvania and occupied Wallachia and Dobruja, including Bucharest and the strategically important oil fields, by the end of 1916. In 1917, despite fierce Romanian resistance, especially at Mărăşeşti, due to Russia's withdrawal from the war following the October Revolution, Romania, being almost completely surrounded by the Central Powers, was forced to also drop from the war, signing the Armistice of Focșani and next year, in May 1918, the Treaty of Bucharest. But after the successful offensive on the Thessaloniki front which put Bulgaria out of the war, Romania's government quickly reasserted control and put an army back into the field on November 10, 1918, a day before the war ended in Western Europe. Following the proclamation of the union of Transylvania with the Kingdom of Romania on December 1, 1918, by the representatives of Transylvanian Romanians gathered at Alba Iulia, Transylvania was soon united with the Kingdom, as was Bessarabia earlier in 1918, since the power vacuum in Russia caused by the civil war there allowed Sfatul Țării, or National Council, to proclaim the Union of Bessarabia with Romania. War with the Hungarian Soviet Republic in 1919 resulted in the occupation of Budapest by Romanian troops and the end of Béla Kun's Bolshevik regime.

Union with Transylvania, Bessarabia and Bukovina

At the Paris Peace Conference, Romania received territories of Transylvania, part of Banat and other territories from Hungary, while as well Bessarabia (Eastern Moldavia between Prut and Dniester rivers) and Bukovina. In the Treaty of Trianon, Hungary renounced in favor of Romania all the claims of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy over Transylvania.[7] The union of Romania with Bukovina was ratified in 1919 in the Treaty of Saint Germain,[8] and in 1920 some of the Western powers recognized Romanian rule over Bessarabia by the Treaty of Paris.[9] Thus, Romania in 1920 was more than twice the size it had been in 1914. The last territorial change during this period came in 1923, when a few border settlements were exchanged between Romania and Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. The most notable Romanian acquisition was the town of Jimbolia, while the most notable Yugoslav acquisition was the town of Jaša Tomić.[10][11] Although the country had no further territorial claims, it aroused the enmity of Bulgaria, and especially Hungary and the Soviet Union. It is worth noting, however, that the Treaty of Paris - recognizing the union with Bessarabia - never came into effect because one of its signatories, Japan, refused to ratify it. This meant that the union was not recognized by the international society, making it - unlike the other provinces - more of a de facto union than an official, de jure one.[12] Furthermore, President Wilson left the peace conference to emphasize his disagreements, following the U.S. Congress did not ratify the Treaty of Trianon, the United States of America and the Kingdom of Hungary signed a separate peace treaty on 29 August 1921.[13]

Greater Romania now encompassed a significant minority population, especially of Hungarians, and faced the difficulty of assimilation. Transylvania had significant Hungarian and German population, and with a historically contemptuous attitude towards Romanians, they now feared reprisals. Both groups were effectively excluded from politics as the postwar Romanian regime passed an edict stating that all personnel employed by the state had to speak Romanian. The new Romanian state was also a highly centralized one, so it was unlikely that the Hungarian or German minorities would exercise political influence without personal connections in the government in Bucharest. The Romanian policy towards Hungarians and Germans was fairly balanced, and both were permitted to have schools in their respective languages and the freedom to publish written material. Judicial hearings would also be conducted in their native official languages.

Lesser minorities were not as well treated because of their small numbers and because they had no outside power to support them. Jews in particular were highly unpopular.

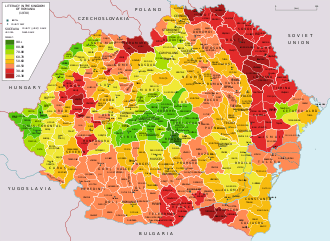

Romanian education was a mixed bag. While the nobility had a long tradition of sending their sons to Europe's finest schools, the educated were a tiny minority. Transylvania had the most educated population in Romania, while Bessarabia fared the worst. While all Romanian children were required to attend at least four years of school, few actually went and the system was designed to separate those who would go on to higher education from those who would not. While this was partially necessary due to limited resources, it also ensured that peasants had almost no chance of becoming educated.

High school and college education in Romania was modeled after French schools. Students undertook a rigid curriculum based around the liberal arts and anyone who could pass was very well-educated. However, Romania suffered from the same problem as the rest of Eastern Europe, which was that most students preferred abstract subjects like theology, philosophy, literature, the fine arts, and law (in the philosophical rather than the applied sense) to practical ones like science, business, and engineering.

The peasant population was among the poorest in the region, a situation aggravated by one of Europe's highest birth rates. As elsewhere, peasants everywhere were convinced that land reform would solve their problems, and after the war they began to clamor loudly for such action, which led to the 1921 land reform. But it did precious little to improve productivity, especially since the richness of Romania's soil was negated by a lack of modern farming techniques. Agricultural exports could not compete with those of Western Europe and North America, and the onset of the Great Depression caused the market for them to completely dry up.

In 1919, a staggering 72% of Romanians were engaged in agriculture. And due to one of Europe's highest birth rates, as much as a quarter of the rural population was unnecessary surplus. Farming was primitive and machinery and chemical fertilizers almost unheard of. The Regat (prewar Romania) was traditionally a land of large estates worked by peasants who either had no land of their own or else dwarf plots. The situation in Transylania and Bessarabia was marginally better. After peasant calls for land reform snowballed into an avalanche, King Ferdinand had to oblige, especially once the Russian Revolution had encouraged peasants to take the matter in their own hands. In the end, it did nothing to remedy the basic problems of rural overpopulation and technological backwardness. The redistributed plots were invariably too small to feed their owners and peasants also could not overcome their tradition of growing grain over cash crops. Since draft animals were rare, to say nothing of machinery, actual agricultural productivity was worse than before.

Despite the land reforms, landowners still controlled up to 30% of Romania's soil, also including the forests that peasants needed for fuel. Romania also had little opportunity to export agricultural products since the biggest ones like grain couldn't possibly compete with producers in the United States or elsewhere.

Romanian industry was quite well-developed due to an abundance of natural resources, especially oil. Lumber and various minerals were produced mainly for export, but most industry was owned by foreign companies, over 70% during the interwar period.

Industrial development

Pre-Kingdom Era to World War I

At the time of the proclamation of the Kingdom, there were already several industrial facilities in the country: The Assan and Olamazu steam mills, built in 1853 and 1862 respectively, a brick factory built in 1865, and two sugar factories built in 1873, among others. In 1857, the first oil refinery in the world was built at Ploiești.[14] In 1880, after several railways were built, the CFR was founded. After proclamation of the Kingdom, the pre-established industrial facilities began to be highly developed: 6 more, larger, sugar factories were built and the railway network was expanded more. Another, more modern brick factory was built in 1891. Despite all of these industrial achievements, the overwhelming majority of Romania's economy remained the agriculture.[15]

Interwar years

Despite the destruction provoked by the First World War, Romanian industry managed significant growth, as a result of new establishments and development of the older ones. The MALAXA industrial engineering and manufacturing company was established in 1921 by Romanian industrialist Nicolae Malaxa and dealt especially with rolling stock maintenance and manufacturing. It developed rapidly, and by 1930 Romania had managed to cease importing locomotives altogether, all required rolling stock being supplied by the local industry.[16] Industrial facilities acquired along with the new provinces, such as the Reșița works, also contributed to the rapid development of Romanian heavy industry. Other important establishments were the Copșa Mică works, producing non-ferrous metals and the Romanian Optical Enterprise. Construction also developed, as great monuments like the Caraiman Cross (1928), Arcul de Triumf (1936) and the Mausoleum of Mărășești (1938) were erected. The oil industry was also greatly expanded, making Romania one of the top oil exporters by the late 1930s, which also attracted German and Italian interest.

Armament industry

Romanian military industry during World War I was mainly focused on converting various fortification guns into field and anti-aircraft artillery. Up to 334 German 53 mm Fahrpanzer guns, 93 French 57 mm Hotchkiss guns, 66 Krupp 150 mm guns and dozens more 210 mm guns were mounted on Romanian-built carriages and transformed into mobile field artillery, with 45 Krupp 75 mm guns and 132 Hotchkiss 57 mm guns being transformed into anti-aircraft artillery. The Romanians also upgraded 120 German Krupp 105 mm howitzers, the result being the most effective field howitzer in Europe at that time. Romania even managed to design and build from scratch its own model of mortar, the 250 mm Negrei Model 1916.[17] Other Romanian technological assets include the building of Vlaicu III, the world's first aircraft made of metal.[18] The Romanian Navy possessed the largest warships on the Danube. They were a class of 4 river monitors, built locally at the Galați shipyard using parts manufactured in Austria-Hungary, and the first one launched was Lascăr Catargiu, in 1907.[19][20] The Romanian monitors displaced almost 700 tons, were armed with three 120 mm naval guns in 3 turrets, two 120 mm naval howitzers, four 47 mm anti-aircraft guns and two 6.5 machine guns.[21] The monitors took part in the Battle of Turtucaia and the First Battle of Cobadin. The Romanian-designed Schneider 150 mm Model 1912 howitzer was considered one of the most modern field guns on the Western Front.[22]

.jpg)

The Romanian armament industry was expanded greatly during the Interwar period and World War II. New factories were constructed, such as the Industria Aeronautică Română and Societatea Pentru Exploatări Tehnice aircraft factories, which produced hundreds of indigenous aircraft, such as IAR 37, IAR 80 and SET 7. Before the war, Romania acquired from France the licence to produce hundreds of Brandt Mle 27/31 and Brandt Mle 1935 mortars, with hundreds more produced during the war,[23] and also the licence to produce 140 French 47 mm Schneider anti-tank guns at the Concordia factory, with 118 produced between 26 May 1939 and 1 August 1940 and hundreds more produced during the war;[24][25] these guns were to be towed by Malaxa Tip UE armored carriers, built since late 1939 at the Malaxa factory under French licence, eventually 126 being built until March 1941. Czechoslovak licence was acquired in 1938 to produce the ZB vz. 30 machine gun, with 5,000 being built at the Cugir gun factory until the start of Operation Barbarossa in June 1941.[26] Romania also acquired the licence to produce the AH-IV tankette, but ultimately only one prototype was built locally.[27] German licence was acquired in 1938 to produce 360 37 mm Rheinmetall anti-aircraft guns, but only 102 were produced until May 1941.[26] British licence was acquired to produce 100 Vickers Model 1931 75 mm anti-aircraft guns at the Reșița works, with the first battery of 6 guns entering service on 1 August 1939, and 100 more guns were built during the war for a total production of 200.[26] On 14 June, Romania launched the first locally-built warship, the minelayer NMS Amiral Murgescu.

During the war, Romania copied and produced hundreds of Soviet M1938 mortars,[25] as well as designing and producing up to 400 75 mm Reșița Model 1943 anti-tank guns. Infantry weapons designed and produced by Romania during the war include the Orița M1941 sub-machinegun and the Argeș flamethrower. Romania also built 30 Vănătorul de care R-35,[28] 34 TACAM T-60, 21 TACAM R-2 tank destroyers and rebuilt 34 captured Soviet Komsomolets armored tractors.[29] A few prototype vehicles were also built, such as the Mareșal tank destroyer, which is credited with being the inspiration for the German Hetzer,[28] a Renault R-35 tank with a T-26 turret[28] and an artillery tractor known as T-1. Warships built include the submarines NMS Rechinul and NMS Marsuinul, a class of 4 minesweepers, 6 Dutch-designed torpedo boats[30] and 2 gunboats.[31]

The Interbellum (inter-war) years

The Romanian expression România Mare (literal translation "Great Romania", but more commonly rendered in English: "Greater Romania") generally refers to the Romanian state in the interwar period, and by extension, to the territory Romania covered at the time. Romania achieved at that time its greatest territorial extent (almost 300,000 km²[32]). At the 1930 census, there were over 18 million inhabitants in Romania.

The resulting "Greater Romania" did not survive World War II. Until 1938, Romania's governments maintained the form, if not always the substance, of a liberal constitutional monarchy. The National Liberal Party, dominant in the years immediately after World War I, became increasingly clientelist and nationalist, and in 1927 was supplanted in power by the National Peasants' Party. Between 1930 and 1940 there were over 25 separate governments; on several occasions in the last few years before World War II, the rivalry between the fascist Iron Guard and other political groupings approached the level of a civil war.

Upon the death of king Ferdinand in 1927, his son Prince Carol was prevented from succeeding him because of previous marital scandals that had resulted in his renunciation of rights to the throne. After living three years in exile, with his brother Nicolae serving as regent and his young son Michael as king, Carol changed his mind and with the support of the ruling National Peasants' Party he returned and proclaimed himself king.

Iuliu Maniu, leader of the National Peasants' Party, engineered Carol's return on the basis of a promise that he would forsake his mistress Magda Lupescu, and Lupescu herself had agreed to the arrangement. However, it became clear upon Carol's first re-encounter with his former wife, Elena, that he had no interest in a reconciliation with her, and Carol soon arranged for Magda Lupescu's return to his side. Her unpopularity was to be a millstone around Carol's neck for the rest of his reign, particularly because she was widely viewed as his closest advisor and confidante. Maniu and his National Peasant Party shared the same general political aims of the Iron Guard: both fought against the corruption and dictatorial policies of King Carol II and the National Liberal Party.[33]

The worldwide Great Depression that started in 1929 destabilised Romania. The early 1930s were marked by social unrest, high unemployment, and strikes. In several instances, the Romanian government violently repressed strikes and riots, notably the 1929 miners' strike in Valea Jiului and the strike in the Griviţa railroad workshops. In the mid-1930s, the Romanian economy recovered and the industry grew significantly, although about 80% of Romanians were still employed in agriculture. French economic and political influence was predominant in the early 1920s but then Germany became more dominant, especially in the 1930s.[34]

As the 1930s progressed, Romania's already shaky democracy slowly deteriorated toward fascist dictatorship. The constitution of 1923 gave the king free rein to dissolve parliament and call elections at will; as a result, Romania was to experience over 25 governments in a single decade.

Increasingly, these governments were dominated by a number of anti-Semitic, ultra-nationalist, and mostly at least quasi-fascist parties. The National Liberal Party steadily became more nationalistic than liberal, but nonetheless lost its dominance over Romanian politics. It was eclipsed by parties like the (relatively moderate) National Peasants' Party and its more radical Romanian Front offshoot, the National-Christian Defense League (LANC) and the Iron Guard. In 1935, LANC merged with the National Agrarian Party to form the National Christian Party (NCP). The quasi-mystical fascist Iron Guard was an earlier LANC offshoot that, even more than these other parties, exploited nationalist feelings, fear of communism, and resentment of alleged foreign and Jewish domination of the economy.

Already, the Iron Guard had embraced the politics of assassinations, and various governments had reacted more or less in kind. On December 10, 1933, Liberal prime minister Ion Duca "dissolved" the Iron Guard, arresting thousands; consequently, 19 days later he was assassinated by Iron Guard legionnaires.

Throughout the 1930s, these nationalist parties had a mutually distrustful relationship with King Carol II. Nonetheless, in December 1937, the king appointed LANC leader, the poet Octavian Goga as prime minister of Romania's first Fascist government. Around this time, Carol met with Adolf Hitler, who expressed his wish to see a Romanian government headed by the pro-Nazi Iron Guard. Instead, on 10 February 1938 King Carol II used the occasion of a public insult by Goga toward Lupescu as a reason to dismiss the government and institute a short-lived royal dictatorship, sanctioned seventeen days later by a new constitution under which the king named personally not only the prime minister but all the ministers.

In April 1938, King Carol had Iron Guard leader Corneliu Zelea Codreanu (aka "The Captain") arrested and imprisoned. On the night of 29–30 November 1938, Codreanu and several other legionnaires were killed while purportedly attempting to escape from prison. It is generally agreed that there was no such escape attempt, but that they were murdered in retaliation for a series of assassinations by Iron Guard commandos.

The royal dictatorship was brief. On 7 March 1939, a new government was formed with Armand Călinescu as prime minister; on 21 September 1939, three weeks after the start of World War II, Călinescu, in turn, was also assassinated by legionnaires avenging Codreanu's murder.

In 1939, Germany and the Soviet Union signed the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, which stipulated, among other things, the Soviet "interest" in Bessarabia. After the 1940 territorial losses and growing increasingly unpopular, Carol was compelled to abdicate and name general Ion Antonescu as the new Prime-Minister with full powers in ruling the state by royal decree.[35]

Romanian overseas territories

Between 13 August 1934 and 7 April 1939, Romania administered a territory in the Albanian town of Sarandë (Saranda in Romanian). The territory was gifted by Albania to Nicolae Iorga, a Romanian historian and politician, in recognition for his scholarly activity on Albanian history. Iorga donated half of that territory to the Romanian state, thus giving Romania its only ever overseas territory and a coast on the Adriatic.[36][37]

The concession was acquired by Romania through soft power, and thus elements of the Romanian Armed Forces were never deployed to the area. The territory was ultimately conquered by Italy, along with all of Albania, in April 1939.

Monarchs

King Carol I (1881–1914)

King Carol I (1881–1914) King Ferdinand I (1914–1927)

King Ferdinand I (1914–1927) Prince Nicholas (Regent) (1927–1930)

Prince Nicholas (Regent) (1927–1930) King Carol II (1930–1940)

King Carol II (1930–1940) King Michael I (1927–1930; 1940–1947)

King Michael I (1927–1930; 1940–1947)

Demographics

According to the 1930 Romanian Census, Romania had a population of 18,057,028. Romanians made up 71.9% of the population and 28.1% of the population were ethnic minorities.

| Ethnicity | number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Romanians | 12,981,324 | 71.9 |

| Hungarians | 1,425,507 | 7.9 |

| Germans | 745,421 | 4.1 |

| Jews | 728,115 | 4.0 |

| Ruthenians and Ukrainians | 582,115 | 3.2 |

| Russians | 409,150 | 2.3 |

| Bulgarians | 366,384 | 2.0 |

| Romani | 262,501 | 1.5 |

| Turks | 154,772 | 0.9 |

| Gagauzians | 105,750 | 0.6 |

| Czechs and Slovaks | 51,842 | 0.3 |

| Serbs, Croats and Slovenes | 51,062 | 0.3 |

| Poles | 48,310 | 0.3 |

| Greeks | 26,495 | 0.1 |

| Tatars | 22,141 | 0.1 |

| Armenians | 15,544 | 0.0 |

| Hutsuls | 12,456 | 0.0 |

| Albanians | 4,670 | 0.0 |

| Others | 56,355 | 0.3 |

| Undeclared | 7,114 | 0.0 |

| Total | 18,057,028 | 100.0 |

Cities

Largest cities as per 1930 census:

| Rank | Name | Population |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bucharest | 570,881 (639,0401) |

| 2 | Chișinău (now located in Moldova) | 114,896 |

| 3 | Cernăuți (now located in Ukraine) | 112,427 |

| 4 | Iași | 102,872 |

| 5 | Cluj | 100,844 |

| 6 | Galați | 100,611 |

| 7 | Timișoara | 91,580 |

Notes: 1 - including 12 suburban communities.

Two of Romania's seven largest cities in 1930 are currently located outside of Romania as a result of World War II border changes.

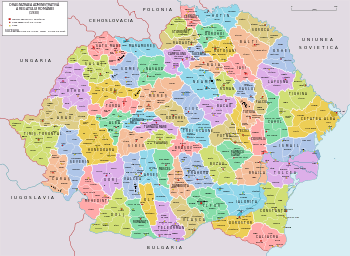

Administrative division

After Independence, the Romanian Old Kingdom was divided into 33 counties.

After World War I, as a result of the 1925 administrative unification law, the territory was divided into 71 counties, 489 districts (plăși) and 8,879 communes.

In 1938, King Carol II promulgated a new Constitution, and subsequently he had the administrative division of the Romanian territory changed. Ten ținuturi (approximate translation: "lands") were created (by merging the counties) to be ruled by rezidenți regali (approximate translation: "Royal Residents") - appointed directly by the King. This administrative reform did not last and the counties were re-established after the fall of Carol's regime.

Timeline (1859–1940)

| • 1859 – | Alexander John Cuza unites Moldavia and Wallachia under his personal rule. |

| • 1862 – | Formal union of Moldavia and Wallachia to form principality of Romania. |

| • 1866 – | Cuza forced to abdicate and a foreign dynasty is established. Carol I signed the first modern Constitution. |

| • 1877 – | April 16. Treaty by which the Russian troops are allowed to pass through Romanian territory April 24. Russia declares war on the Ottoman Empire and its troops enter Romania May 9. Romanian independence declared by the Romanian parliament, start of Romanian War of Independence May 10. Carol I ratifies independence declaration |

| • 1878 – | Under Treaty of Berlin, Ottoman Empire recognizes Romanian independence. Romania ceded southern Bessarabia to Russia. |

| • 1881 – | Carol I was proclaimed King of Romania on March 14. |

| • 1894 – | Leaders of the Transylvanian Romanians who sent a Memorandum to the Austrian Emperor demanding national rights for the Romanians are found guilty of treason. |

| • 1907 – | Violent peasant revolts crushed throughout Romania, thousands of persons killed. |

| • 1914 – | Death of Carol I, succeeded by his nephew Ferdinand. |

| • 1916 – | August. Romania enters World War I on the Entente side. December. Romanian Treasure sent to Russia for safekeeping but was seized by Soviets after the Romanian army refused to withdraw from Bessarabia. |

| • 1918 – | Greater Romania is created. |

| By the Treaty of Versailles, Romania agreed to grant citizenship to the former citizens of Russian and Austro-Hungarian Empires living in the new Romanian territories. | |

| • 1919 – | A military conflict occurs between Romania and Hungarian Soviet Republic led by Béla Kun. The Romanian Army takes over Budapest on 4 August 1919. The city is ruled by a military administration until 16 November 1919. The Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye officially assigns Bukovina to Romania. |

| • 1920 – | The Treaty of Trianon officially assigns Transylvania, Banat and Partium to Romania. Little Entente alliance with Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia initiated. |

| • 1921 – | A major and radical agrarian reform. Polish–Romanian Alliance established. |

| • 1923 – | The 1923 Constitution is adopted based on a National Liberal Party project. National-Christian Defense League (LANC) founded. |

| • 1924 – | LANC member (later Iron Guard founder) Corneliu Zelea Codreanu assassinates the Prefect of Police in Iaşi, but is acquitted. |

| • 1926 – | Liberal Electoral Law adopted. Franco-Romanian Treaty. |

| • 1927 – | The National Peasants' Party takes over the government from the National Liberal Party. The Legion of the Archangel Michael, later the Iron Guard, splits from LANC. Michael (Mihai) becomes king under a regency regime. |

| • 1929 – | Beginning of the Great Depression. |

| • 1930 – | Carol II crowned King. |

| • 1931 – | First ban on Iron Guard. |

| • 1933 – | 16 February. Griviţa Railcar Workshops strike violently put down by police. 10 December. Prime Minister Ion Duca "dissolves" the Iron Guard, arresting thousands; 19 days later he is assassinated by Iron Guard legionnaires. |

| • 1935 – | LANC and National Agrarian Party merge to form the fascist National Christian Party (NCP). |

| • 1937 – | Electoral "non-aggression pact" between the National Peasants' Party and Iron Guard, later adding the Agrarian Union. Romanian Communist Party denounces pact, but, in practice, supports the National-Peasants. LANC forms government, but is rapidly in conflict with Carol II over his Jewish mistress. |

| • 1938 – | 10 February. Royal dictatorship declared. New constitution adopted 27 February. 29–30 November. Iron Guard leader Codreanu and other legionnaires shot on the King's orders. |

| • 1939 – | 7 March. Armand Călinescu forms government. 23 August. Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact stipulates Soviet "interest" in Bessarabia. 1 September. Germany invades Poland. Start of World War II. 21 September. Călinescu assassinated by Iron Guard legionnaires. |

| • 1940 – | 6 September. After the forced abdication of King Carol II, his 19-year-old son Michael I assumes the throne, being obliged to grant dictatorial powers to Prime Minister and Conducător Ion Antonescu. 14 September. The Kingdom of Romania is supplanted by a short-lived dictatorship called the National Legionary State. |

- Selection of newspapers of the Kingdom of Romania

Alegătorul liber, January 23, 1875

Alegătorul liber, January 23, 1875 Bukarester Tagblatt, August 10, 1880 (in German)

Bukarester Tagblatt, August 10, 1880 (in German) Voința naționala, November 1, 1884

Voința naționala, November 1, 1884 Opinia, August 22, 1913

Opinia, August 22, 1913

Kings of Romania (1881–1947)

| Name | Lifespan | Reign start | Reign end | Notes | Family | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Charles I

| 20 April 1839 – 10 October 1914 (aged 75) | 15 March 1881 | 10 October 1914 | Prince Karl of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen elected Sovereign Prince of Romania 20 April 1866 | Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen |  |

Ferdinand I

| 24 August 1865 – 20 July 1927 (aged 61) | 10 October 1914 | 20 July 1927 | Nephew of Carol I | Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen |  |

| Michael I (1st reign) [39]

| 25 October 1921 – 5 December 2017 (aged 96) | 20 July 1927 | 8 June 1930 | Grandson of Ferdinand I | Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen | .jpg) |

Charles II

| 15 October 1893 – 4 April 1953 (aged 59) | 8 June 1930 | 6 September 1940 | Son of Ferdinand I | Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen |  |

| Michael I (2nd reign) [40]

| 25 October 1921 – 5 December 2017 (aged 96) | 6 September 1940 | 30 December 1947 | Son of Carol II; Restored | Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen |  |

Queens-consort of Romania

| Name | Lifespan | Reign start | Reign end | Notes | Family | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elisabeth | 29 December 1843 – 2 March 1916 (aged 72) | 15 March 1881 | 10 October 1914 | Consort of King Carol I | Wied |  |

| Marie | 29 October 1875 – 18 July 1938 (aged 62) | 10 October 1914 | 20 July 1927 | Consort of King Ferdinand | Saxe-Coburg and Gotha |  |

| Helen | 2 May 1896 – 28 November 1982 (aged 86) | Consort of Crown Prince Carol Queen Mother on Michael I's 2nd accession | Greece (Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg) |  | ||

| Anne | 18 September 1923 – 1 August 2016 (aged 92) | Consort of King Michael I Wed after husband's deposition | Bourbon-Parma |  |

Pretenders to the Romanian throne

| Pretender | Portrait | Lifespan | Pretending from | Pretending until |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Michael I |  | 25 October 1921 – 5 December 2017 (aged 96) | 30 December 1947 | 5 December 2017 |

Timeline

This is a graphical lifespan timeline of Kings, Heirs and Pretenders to the Romanian throne. The kings, heirs and the pretenders are listed in chronological order.

Royal Standards

.svg.png) Royal Standard (1881–1922)

Royal Standard (1881–1922).svg.png) Royal Standard (1922–1947)

Royal Standard (1922–1947)

See also

- Romanian War of Independence

- Historical administrative divisions of Romania

References

- "Constitutiunea din 1923" (in Romanian). Legislatie pentru Democratie. Retrieved 19 September 2011.

- Dennis Deletant, Hitler's Forgotten Ally: Ion Antonescu and His Regime, Romania, 1940–1944, Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2006. ISBN 1-4039-9341-6

- Ioan Scurtu (2005). "Istoria contemporana a României (1918-2005)" (in Romanian). Bucharest. Retrieved 19 September 2011.

- Institutul Central de Statistică (1943). "Indicatorul localităților din România" (PDF) (in Romanian). Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- "Timeline". Archived from the original on 2016-12-19.

- "Romania - The Crimean War and Unification".

- "Text of the Treaty of Trianon". World War I Document Archive. Retrieved 2007-12-07.

- Bernard Anthony Cook (2001). Europe Since 1945: An Encyclopedia. Taylor&Francis. p. 162. ISBN 0-8153-4057-5. Retrieved 2007-12-07.

- Malbone W. Graham (October 1944). "The Legal Status of the Bukovina and Bessarabia". The American Journal of International Law. American Society of International Law. 38 (4): 667–673. doi:10.2307/2192802. JSTOR 2192802.

- Dan Petre, Hotarele românismului în date (Ed. Litera Internațional, București, 2005), pp. 106-107

- Peter Jordan (OKmsr Dr.), Österreichisches Ost- und Südosteuropa-Institut, 1989, Atlas Ost- und Südosteuropa: aktuelle Karten zu Ökologie, Bevölkerung und Wirtschaft, Issue 2, p. 27

- Takako Ueta, Eric Remacle, Peter Lang, 2005, Japan and Enlarged Europe: Partners in Global Governance, p. 81

- 1921. évi XLVIII. törvénycikk az Amerikai Egyesült-Államokkal 1921. évi augusztus hó 29. napján Budapesten kötött békeszerződés becikkelyezéséről - XLVIII. Act of 1921 about the enactment the peace treaty signed in Budapest on 29. August 1921 with the United States of America - http://www.1000ev.hu/index.php?a=3¶m=7504

- "WORLD EVENTS: 1844-1856". PBS.org. Retrieved 2009-04-22.

world's first oil refinery

- "industria romana inainte de primul razboi mondial Archives - Romania Military".

- "Metallic Welded Constructions. Faur Bucharest Romania".

- Adrian Storea, Gheorghe Băjenaru, Artileria română în date și imagini (Romanian artillery in data and pictures), pp. 40, 49, 50, 54, 59, 61, 63, 65 and 66 (in Romanian)

- Jozef Wilczynski, Technology in Comecon: Acceleration of Technological Progress Through Economic Planning and the Market, p. 243

- International Naval Research Organization, Warship International, Volume 21, p. 160

- Frederick Thomas Jane, Jane's Fighting Ships, p. 343

- Robert Gardiner, Conway's All the World Fighting Ships 1906–1921, p. 422

- Adrian Storea, Gheorghe Băjenaru, Artileria română în date și imagini (Romanian artillery in data and pictures), p. 53 (in Romanian)

- Third Axis. Fourth Ally. Romanian Armed Forces in the European War, 1941-1945, pp. 29, 30, 75 and 147

- Dan Ovidiu Pintilie, Istoricul societății Concordia 1907-1948, p. 142 (in Romanian)

- Third Axis. Fourth Ally. Romanian Armed Forces in the European War, 1941-1945, p. 75

- Third Axis. Fourth Ally. Romanian Armed Forces in the European War, 1941-1945, p. 29

- Charles K. Kliment, Vladimir Francev, Czechoslovak Armored Fighting Vehicles, pp. 113-134

- Steven J. Zaloga, Tanks of Hitler's Eastern Allies 1941-45, p. 31

- Third Axis. Fourth Ally. Romanian Armed Forces in the European War, 1941-1945, p. 220

- Spencer C. Tucker, World War II at Sea: An Encyclopedia: An Encyclopedia, p. 633

- Cristian Crăciunoiu, Romanian Navy torpedo boats

- "Statul national unitar (România Mare 1919 - 1940)". Istoria romanilor din cele mai vechi timpuri pana astazi (in Romanian). Media.ici.ro. Archived from the original on 2010-01-08. Retrieved 19 September 2011.

- Rebecca Ann Haynes, "Reluctant allies? Iuliu Maniu and Corneliu Zelea Codreanu against King Carol II of Romania." Slavonic and East European Review (2007): 105-134. online

- William A. Hoisington Jr, "The Struggle for Economic Influence in Southeastern Europe: The French Failure in Romania, 1940." Journal of Modern History 43.3 (1971): 468-482.

- Ioan Scurtu; Theodora Stănescu-Stanciu; Georgiana Margareta Scurtu. "Decret regal privind investirea generalului Ion Antonescu cu depline puteri". Istoria românilor între anii 1918–1940 (in Romanian). Archived from the original on 2 October 2011. Retrieved 19 September 2011.

- Constantin Hamangiu, George Alexianu, Impt. Centrală, 1938, Codul general al României: (Codurile, legile și regulamentele în vigoare) Intocmit după textele oficiale, Volume 26, Part 2, p. 1318 (in Romanian)

- Virgil Cândea, Editura Enciclopedică, 1998, Mărturii româneşti peste hotare: mică enciclopedie de creaţii româneşti şi de izvoare despre Români în colecţii din străinătate. India - Olanda : supliment Albania - Grecia, Volume 2, p. 2 (in Romanian)

- Populaţia pe Neamuri (in Romanian). Institutul Central de Statistică. pp. XXIV. Retrieved 2011-10-27.

- Nicholas ruling as Prince Regent.

- With Ion Antonescu as Conducător, from 6 September 1940 to 23 August 1944.

Further reading

- Great Britain. Admiralty. A handbook of Roumania (1920) primary source that focuses on prewar economy and society online free

- Treptow, Kurt W. A history of Romania (1996).

External links

- Lampe, John R. (1982). Balkan Economic History, 1550–1950: From Imperial Borderlands to Developing Nations. ISBN 0-253-30368-0.