Athenian democracy

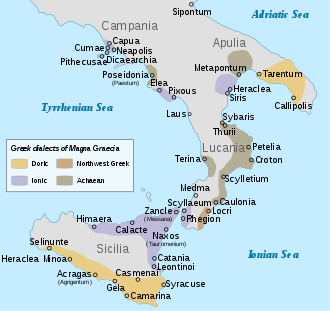

Athenian democracy developed around the sixth century BC in the Greek city-state (known as a polis) of Athens, comprising the city of Athens and the surrounding territory of Attica. Athenian democracy is often described as the first known democracy in the world. Other Greek cities set up democracies, most following the Athenian model, but none are as well documented as Athens' democracy.

Athens practiced a political system of legislation and executive bills. Participation was far from open to all residents, but was instead limited to adult, male citizens (i.e., not a foreign resident, regardless of how many generations of the family had lived in the city, nor a slave, nor a woman), who "were probably no more than 30 percent of the total adult population".[1]

Solon (in 594 BC), Cleisthenes (in 508/7 BC), and Ephialtes (in 462 BC) contributed to the development of Athenian democracy. Cleisthenes broke up the power of the nobility by organizing citizens into ten groups based on where they lived, rather than on their wealth. The longest-lasting democratic leader was Pericles. After his death, Athenian democracy was twice briefly interrupted by oligarchic revolutions towards the end of the Peloponnesian War. It was modified somewhat after it was restored under Eucleides; the most detailed accounts of the system are of this fourth-century modification, rather than the Periclean system. Democracy was suppressed by the Macedonians in 322 BC. The Athenian institutions were later revived, but how close they were to a real democracy is debatable.

Etymology

The word "democracy" (Greek: δημοκρατία) combines the elements dêmos (δῆμος, which means "people") and krátos (κράτος, which means "force" or "power"), and thus means literally "people power". In the words "monarchy" and "oligarchy", the second element comes from archē (ἀρχή), meaning "beginning (that which comes first)", and hence also "first place or power", "sovereignty". One might expect, by analogy, that the term "demarchy" would have been adopted for the new form of government introduced by Athenian democrats. However, the word "demarchy" (δημαρχία) had already been taken and meant "mayoralty", the office or rank of a high municipal magistrate. (In present-day use, the term "demarchy" has acquired a new meaning.)

It is unknown whether the word "democracy" was in existence when systems that came to be called democratic were first instituted. The first conceptual articulation of the term is generally accepted to be c. 470 BC with Aeschylus' The Suppliants (l. 604) with the line sung by the Chorus: δήμου κρατούσα χειρ. This approximately translates as the "people's hand of power", and in the context of the play it acts as a counterpoint to the inclination of the votes cast by the people, i.e. that authority as implemented by the people in the Assembly has power. The word is then completely attested in the works of Herodotus (Histories 6.43.3) in both a verbal passive and nominal sense with the terms δημοκρατέομαι and δημοκρατία. Herodotus wrote some of the earliest surviving Greek prose, but this might not have been before 440 or 430 BC. Around 460 BC an individual is known with the name of Democrates,[2] a name possibly coined as a gesture of democratic loyalty; the name can also be found in Aeolian Temnus.[3]

History

Development

Athens was never the only polis in Ancient Greece that instituted a democratic regime. Aristotle points to other cities that adopted governments in the democratic style. However, accounts of the rise of democratic institutions are in reference to Athens, since only this city-state had sufficient historical records to speculate on the rise and nature of Greek democracy.[4]

Before the first attempt at democratic government, Athens was ruled by a series of archons or chief magistrates, and the Areopagus, made up of ex-archons. The members of these institutions were generally aristocrats. In 621 BC, Draco replaced the prevailing system of oral law by a written code to be enforced only by a court of law.[5][6] In 594 BC, Solon, premier archon at the time, issued reforms that defined citizenship in a way that gave each free resident of Attica a political function: Athenian citizens had the right to participate in assembly meetings. By granting the formerly aristocratic role to every free citizen of Athens who owned property, Solon reshaped the social framework of the city-state. Under these reforms, the boule (a council of 400 members, with 100 citizens from each of Athens's four tribes) ran daily affairs and set the political agenda.[5] The Areopagus, which formerly took on this role, remained but thereafter carried on the role of "guardianship of the laws".[7] Another major contribution to democracy was Solon's setting up of an Ecclesia or Assembly, which was open to all the male citizens.

In 561 BC, the nascent democracy was overthrown by the tyrant Peisistratos but was reinstated after the expulsion of his son, Hippias, in 510. Cleisthenes issued reforms in 508 and 507 BC that undermined the domination of the aristocratic families and connected every Athenian to the city's rule. Cleisthenes formally identified free inhabitants of Attica as citizens of Athens, which gave them power and a role in a sense of civic solidarity.[8] He did this by making the traditional tribes politically irrelevant and instituting ten new tribes, each made up of about three trittyes, each consisting of several demes. Every male citizen over 18 had to be registered in his deme.[9]

The third set of reforms was instigated by Ephialtes in 462/1. While Ephialtes's opponents were away attempting to assist the Spartans, he persuaded the Assembly to reduce the powers of the Areopagus to a criminal court for cases of homicide and sacrilege. At the same time or soon afterward, the membership of the Areopagus was extended to the lower level of the propertied citizenship.[10]

In the wake of Athens's disastrous defeat in the Sicilian campaign in 413 BC, a group of citizens took steps to limit the radical democracy they thought was leading the city to ruin. Their efforts, initially conducted through constitutional channels, culminated in the establishment of an oligarchy, the Council of 400, in the Athenian coup of 411 BC. The oligarchy endured for only four months before it was replaced by a more democratic government. Democratic regimes governed until Athens surrendered to Sparta in 404 BC, when the government was placed in the hands of the so-called Thirty Tyrants, who were pro-Spartan oligarchs.[11] After a year, pro-democracy elements regained control, and democratic forms persisted until the Macedonian army of Phillip II conquered Athens in 338 BC.[12]

Aftermath

Alexander the Great had led a coalition of the Greek states to war with Persia in 336 BC, but his Greek soldiers were hostages for the behavior of their states as much as allies. His relations with Athens were already strained when he returned to Babylon in 324 BC; after his death, Athens and Sparta led several Greek states to war with Macedon and lost.[13]

This led to the Hellenistic control of Athens, with the Macedonian king appointing a local agent as political governor in Athens. However, the governors, like Demetrius of Phalerum, appointed by Cassander, kept some of the traditional institutions in formal existence, although the Athenian public would consider them to be nothing more than Macedonian puppet dictators. Once Demetrius Poliorcetes ended Cassander's rule over Athens, Demetrius of Phalerum went into exile and the democracy was restored in 307 BC. However, by now Athens had become "politically impotent".[14] An example of this was that, in 307, in order to curry favour with Macedonia and Egypt, three new tribes were created, two in honour of the Macedonian king and his son, and the other in honour of the Egyptian king.

However, when Rome fought Macedonia in 200, the Athenians abolished the first two new tribes and created a twelfth tribe in honour of the Pergamene king. The Athenians declared for Rome, and in 146 BC Athens became an autonomous civitas foederata, able to manage internal affairs. This allowed Athens to practice the forms of democracy, though Rome ensured that the constitution strengthened the city's aristocracy.[15]

Under Roman rule, the archons ranked as the highest officials. They were elected, and even foreigners such as Domitian and Hadrian held the office as a mark of honour. Four presided over the judicial administration. The council (whose numbers varied at different times from 300 to 750) was appointed by lot. It was superseded in importance by the Areopagus, which, recruited from the elected archons, had an aristocratic character and was entrusted with wide powers. From the time of Hadrian, an imperial curator superintended the finances. The shadow of the old constitution lingered on and Archons and Areopagus survived the fall of the Roman Empire.[15]

In 88 BC, there was a revolution under the philosopher Athenion, who, as tyrant, forced the Assembly to agree to elect whomever he might ask to office. Athenion allied with Mithridates of Pontus and went to war with Rome; he was killed during the war and was replaced by Aristion. The victorious Roman general, Publius Cornelius Sulla, left the Athenians their lives and did not sell them into slavery; he also restored the previous government, in 86 BC.[16]

After Rome became an Empire under Augustus, the nominal independence of Athens dissolved and its government converged to the normal type for a Roman municipality, with a Senate of decuriones.[17]

Participation and exclusion

Size and make-up of the Athenian population

Estimates of the population of ancient Athens vary. During the 4th century BC, there might well have been some 250,000–300,000 people in Attica.[1] Citizen families could have amounted to 100,000 people and out of these some 30,000 would have been the adult male citizens entitled to vote in the assembly. In the mid-5th century the number of adult male citizens was perhaps as high as 60,000, but this number fell precipitously during the Peloponnesian War.[18] This slump was permanent, due to the introduction of a stricter definition of citizen described below. From a modern perspective these figures may seem small, but among Greek city-states Athens was huge: most of the thousand or so Greek cities could only muster 1000–1500 adult male citizens each; and Corinth, a major power, had at most 15,000.[19]

The non-citizen component of the population was made up of resident foreigners (metics) and slaves, with the latter perhaps somewhat more numerous. Around 338 BC the orator Hyperides (fragment 13) claimed that there were 150,000 slaves in Attica, but this figure is probably no more than an impression: slaves outnumbered those of citizen stock but did not swamp them.[20]

Citizenship in Athens

Only adult male Athenian citizens who had completed their military training as ephebes had the right to vote in Athens. The percentage of the population that actually participated in the government was 10% to 20% of the total number of inhabitants, but this varied from the fifth to the fourth century BC.[18] This excluded a majority of the population: slaves, freed slaves, children, women and metics (foreign residents in Athens).[21] The women had limited rights and privileges, had restricted movement in public, and were very segregated from the men.[22]

Also excluded from voting were citizens whose rights were under suspension (typically for failure to pay a debt to the city: see atimia); for some Athenians, this amounted to permanent (and in fact inheritable) disqualification. Given the exclusive and ancestral concept of citizenship held by Greek city-states, a relatively large portion of the population took part in the government of Athens and of other radical democracies like it, compared to oligarchies and aristocracies.[18]

Some Athenian citizens were far more active than others, but the vast numbers required for the system to work testify to a breadth of direct participation among those eligible that greatly surpassed any present-day democracy.[18] Athenian citizens had to be descended from citizens; after the reforms of Pericles and Cimon in 450 BC, only those descended from two Athenian parents could claim citizenship.[23] Although the legislation was not retrospective, five years later, when a free gift of grain had arrived from the Egyptian king to be distributed among all citizens, many "illegitimate" citizens were removed from the registers.[24]

Citizenship applied to both individuals and their descendants. It could also be granted by the assembly and was sometimes given to large groups (e.g. Plateans in 427 BC and Samians in 405 BC). However, by the 4th century, citizenship was given only to individuals and by a special vote with a quorum of 6000. This was generally done as a reward for some service to the state. In the course of a century, the number of citizenships so granted was in the hundreds rather than thousands.[25]

Main bodies of government

There were three political bodies where citizens gathered in numbers running into the hundreds or thousands. These are the assembly (in some cases with a quorum of 6000), the council of 500 (boule), and the courts (a minimum of 200 people, on some occasions up to 6,000). Of these three bodies, the assembly and the courts were the true sites of power – although courts, unlike the assembly, were never simply called the demos ('the people'), as they were manned by just those citizens over thirty. Crucially, citizens voting in both were not subject to review and prosecution, as were council members and all other officeholders.

In the 5th century BC, there is often a record of the assembly sitting as a court of judgment itself for trials of political importance and it is not a coincidence that 6,000 is the number both for the full quorum for the assembly and for the annual pool from which jurors were picked for particular trials. By the mid-4th century, however, the assembly's judicial functions were largely curtailed, though it always kept a role in the initiation of various kinds of political trial.

Ecclesia

The central events of the Athenian democracy were the meetings of the assembly (ἐκκλησία, ekklesía). Unlike a parliament, the assembly's members were not elected, but attended by right when they chose. Greek democracy created at Athens was direct, rather than representative: any adult male citizen over the age of 20 could take part,[26] and it was a duty to do so. The officials of the democracy were in part elected by the Assembly and in large part chosen by lottery in a process called sortition.

The assembly had four main functions: it made executive pronouncements (decrees, such as deciding to go to war or granting citizenship to a foreigner), elected some officials, legislated, and tried political crimes. As the system evolved, the last function was shifted to the law courts. The standard format was that of speakers making speeches for and against a position, followed by a general vote (usually by show of hands) of yes or no.

Though there might be blocs of opinion, sometimes enduring, on important matters, there were no political parties and likewise no government or opposition (as in the Westminster system). Voting was by simple majority. In the 5th century at least, there were scarcely any limits on the power exercised by the assembly. If the assembly broke the law, the only thing that might happen is that it would punish those who had made the proposal that it had agreed to. If a mistake had been made, from the assembly's viewpoint it could only be because it had been misled.[27]

As usual in ancient democracies, one had to physically attend a gathering in order to vote. Military service or simple distance prevented the exercise of citizenship. Voting was usually by show of hands (χειροτονία, kheirotonia, 'arm stretching') with officials judging the outcome by sight. This could cause problems when it became too dark to see properly. However, any member could demand that officials issue a recount.[28] For a small category of votes, a quorum of 6,000 was required, principally grants of citizenship, and here small coloured stones were used, white for yes and black for no. At the end of the session, each voter tossed one of these into a large clay jar which was afterwards cracked open for the counting of the ballots. Ostracism required the voters to scratch names onto pieces of broken pottery (ὄστρακα, ostraka), though this did not occur within the assembly as such.

In the 5th century BC, there were 10 fixed assembly meetings per year, one in each of the ten state months, with other meetings called as needed. In the following century, the meetings were set to forty a year, with four in each state month. One of these was now called the main meeting, kyria ekklesia. Additional meetings might still be called, especially as up until 355 BC there were still political trials that were conducted in the assembly, rather than in court. The assembly meetings did not occur at fixed intervals, as they had to avoid clashing with the annual festivals that followed the lunar calendar. There was also a tendency for the four meetings to be aggregated toward the end of each state month.[29]

Attendance at the assembly was not always voluntary. In the 5th century, public slaves forming a cordon with a red-stained rope herded citizens from the agora into the assembly meeting place (Pnyx), with a fine being imposed on those who got the red on their clothes.[30] After the restoration of the democracy in 403 BC, pay for assembly attendance was introduced. This promoted a new enthusiasm for assembly meetings. Only the first 6,000 to arrive were admitted and paid, with the red rope now used to keep latecomers at bay.[31]

The Boule

In 594 BC, Solon is said to have created a boule of 400 to guide the work of the assembly.[32] After the reforms of Cleisthenes, the Athenian Boule was expanded to 500 and was elected by lot every year. Each of Cleisthenes's 10 tribes provided 50 councilors who were at least 30 years old. The Boule's roles in public affairs included finance, maintaining the military's cavalry and fleet of ships, advising the generals, approving of newly elected magistrates, and receiving ambassadors. Most importantly, the Boule would draft probouleumata, or deliberations for the Ecclesia to discuss and approve on. During emergencies, the Ecclesia would also grant special temporary powers to the Boule.[33]

Cleisthenes restricted the Boule's membership to those of zeugitai status (and above), presumably because these classes' financial interests gave them an incentive towards effective governance. A member had to be approved by his deme, each of which would have an incentive to select those with experience in local politics and the greatest likelihood at effective participation in government.[34]

The members from each of the ten tribes in the Boule took it in turns to act as a standing committee (the prytaneis) of the Boule for a period of thirty-six days. All fifty members of the prytaneis on duty were housed and fed in the tholos of the Prytaneion, a building adjacent to the bouleuterion, where the boule met. A chairman for each tribe was chosen by lot each day, who was required to stay in the tholos for the next 24 hours, presiding over meetings of the Boule and Assembly.[35]

The boule also served as an executive committee for the assembly, and oversaw the activities of certain other magistrates. The boule coordinated the activities of the various boards and magistrates that carried out the administrative functions of Athens and provided from its own membership randomly selected boards of ten responsible for areas ranging from naval affairs to religious observances.[36] Altogether, the boule was responsible for a great portion of the administration of the state, but was granted relatively little latitude for initiative; the boule's control over policy was executed in its probouleutic, rather than its executive function; in the former, it prepared measures for deliberation by the assembly, in the latter, it merely executed the wishes of the assembly.[37]

Courts

Athens had an elaborate legal system centered on full citizen rights (see atimia). The age limit of 30 or older, the same as that for office holders but ten years older than that required for participation in the assembly, gave the courts a certain standing in relation to the assembly. Jurors were required to be under oath, which was not required for attendance at the assembly. The authority exercised by the courts had the same basis as that of the assembly: both were regarded as expressing the direct will of the people. Unlike office holders (magistrates), who could be impeached and prosecuted for misconduct, the jurors could not be censured, for they, in effect, were the people and no authority could be higher than that. A corollary of this was that, at least acclaimed by defendants, if a court had made an unjust decision, it must have been because it had been misled by a litigant.[38]

Essentially there were two grades of a suit, a smaller kind known as dike (δίκη) or private suit, and a larger kind known as graphe or public suit. For private suits, the minimum jury size was 200 (increased to 401 if a sum of over 1000 drachmas was at issue), for public suits 501. Under Cleisthenes's reforms, juries were selected by lot from a panel of 600 jurors, there being 600 jurors from each of the ten tribes of Athens, making a jury pool of 6000 in total.[39] For particularly important public suits the jury could be increased by adding in extra allotments of 500. 1000 and 1500 are regularly encountered as jury sizes and on at least one occasion, the first time a new kind of case was brought to court (see graphē paranómōn), all 6,000 members of the jury pool may have attended to one case.[40]

The cases were put by the litigants themselves in the form of an exchange of single speeches timed by a water clock or clepsydra, first prosecutor then defendant. In a public suit the litigants each had three hours to speak, much less in private suits (though here it was in proportion to the amount of money at stake). Decisions were made by voting without any time set aside for deliberation. Jurors did talk informally amongst themselves during the voting procedure and juries could be rowdy, shouting out their disapproval or disbelief of things said by the litigants. This may have had some role in building a consensus. The jury could only cast a 'yes' or 'no' vote as to the guilt and sentence of the defendant. For private suits only the victims or their families could prosecute, while for public suits anyone (ho boulomenos, 'whoever wants to' i.e. any citizen with full citizen rights) could bring a case since the issues in these major suits were regarded as affecting the community as a whole.

Justice was rapid: a case could last no longer than one day and had to be completed by the time the sun set.[41] Some convictions triggered an automatic penalty, but where this was not the case the two litigants each proposed a penalty for the convicted defendant and the jury chose between them in a further vote.[42] No appeal was possible. There was however a mechanism for prosecuting the witnesses of a successful prosecutor, which it appears could lead to the undoing of the earlier verdict.

Payment for jurors was introduced around 462 BC and is ascribed to Pericles, a feature described by Aristotle as fundamental to radical democracy (Politics 1294a37). Pay was raised from 2 to 3 obols by Cleon early in the Peloponnesian war and there it stayed; the original amount is not known. Notably, this was introduced more than fifty years before payment for attendance at assembly meetings. Running the courts was one of the major expenses of the Athenian state and there were moments of financial crisis in the 4th century when the courts, at least for private suits, had to be suspended.[43]

The system showed a marked anti-professionalism. No judges presided over the courts, nor did anyone give legal direction to the jurors. Magistrates had only an administrative function and were laymen. Most of the annual magistracies in Athens could only be held once in a lifetime. There were no lawyers as such; litigants acted solely in their capacity as citizens. Whatever professionalism there was tended to disguise itself; it was possible to pay for the services of a speechwriter or logographer (logographos), but this may not have been advertised in court. Jurors would likely be more impressed if it seemed as though litigants were speaking for themselves.[44]

Shifting balance between assembly and courts

As the system evolved, the courts (that is, citizens under another guise) intruded upon the power of the assembly. Starting in 355 BC, political trials were no longer held in the assembly, but only in a court. In 416 BC, the graphē paranómōn ('indictment against measures contrary to the laws') was introduced. Under this, anything passed or proposed by the assembly could be put on hold for review before a jury – which might annul it and perhaps punish the proposer as well.

Remarkably, it seems that blocking and then successfully reviewing a measure was enough to validate it without needing the assembly to vote on it. For example, two men have clashed in the assembly about a proposal put by one of them; it passes, and now the two of them go to court with the loser in the assembly prosecuting both the law and its proposer. The quantity of these suits was enormous. The courts became in effect a kind of upper house.

In the 5th century, there were no procedural differences between an executive decree and a law. They were both simply passed by the assembly. However, beginning in 403 BC, they were set sharply apart. Henceforth, laws were made not in the assembly, but by special panels of citizens drawn from the annual jury pool of 6,000. These were known as the nomothetai (νομοθέται, 'the lawmakers').[45]

Citizen-initiator

The institutions sketched above – assembly, officeholders, council, courts – are incomplete without the figure that drove the whole system, Ho boulomenos ('he who wishes', or 'anyone who wishes'). This expression encapsulated the right of citizens to take the initiative to stand to speak in the assembly, to initiate a public lawsuit (that is, one held to affect the political community as a whole), to propose a law before the lawmakers, or to approach the council with suggestions. Unlike officeholders, the citizen initiator was not voted on before taking up office or automatically reviewed after stepping down; these institutions had, after all, no set tenure and might be an action lasting only a moment. However, any stepping forward into the democratic limelight was risky. If another citizen initiator chose, a public figure could be called to account for their actions and punished. In situations involving a public figure, the initiator was referred to as a kategoros ('accuser'), a term also used in cases involving homicide, rather than ho diokon ('the one who pursues').[46]

Pericles, according to Thucydides, characterized the Athenians as being very well-informed on politics:

We do not say that a man who takes no interest in politics is a man who minds his own business; we say that he has no business here at all.[47]

The word idiot originally simply meant "private citizen"; in combination with its more recent meaning of "foolish person", this is sometimes used by modern commentators to demonstrate that the ancient Athenians considered those who did not participate in politics as foolish.[48][49][50] But the sense history of the word does not support this interpretation.[51][52]

Although, voters under Athenian democracy were allowed the same opportunity to voice their opinion and to sway the discussion, they were not always successful, and, often, the minority was forced to vote in favor of a motion that they did not agree with.[53]

Archons and the Areopagus

Just before the reforms of Solon in the 7th century BC, Athens was governed by a few archons (three, then later nine) and the council of the Areopagus, which was composed of members powerful noble families. While there seems to have also been a type of citizen assembly (presumably of the hoplite class), the archons and the body of the Areopagus ran the state and the mass of people had no say in government at all before these reforms.[54]

Solon's reforms allowed the archons to come from some of the higher propertied classes and not only from the aristocratic families. Since the Areopagus was made up of ex-archons, this would eventually mean the weakening of the hold of the nobles there as well. However, even with Solon's creation of the citizen's assembly, the Archons and Areopagus still wielded a great deal of power.[55]

The reforms of Cleisthenes meant that the archons were elected by the Assembly, but were still selected from the upper classes.[56] The Areopagus kept its power as 'Guardian of the Laws', which meant that it could veto actions it deemed unconstitutional, however, this worked in practice.[57]

Ephialtes, and later Pericles, stripped the Areopagus of its role in supervising and controlling the other institutions, dramatically reducing its power. In the play The Eumenides, performed in 458, Aeschylus, himself a noble, portrays the Areopagus as a court established by Athena herself, an apparent attempt to preserve the dignity of the Areopagus in the face of its disempowerment.[10]

Officeholders

Approximately 1100 citizens (including the members of the council of 500) held office each year. They were mostly chosen by lot, with a much smaller (and more prestigious) group of about 100 elected. Neither was compulsory; individuals had to nominate themselves for both selection methods. In particular, those chosen by lot were citizens acting without particular expertise. This was almost inevitable since, with the notable exception of the generals (strategoi), each office had restrictive term limits. For example, a citizen could only be a member of the Boule in two non-consecutive years in their life.[58] In addition, there were some limitations on who could hold office. Age restrictions were in place with thirty years as a minimum, rendering about a third of the adult citizen body ineligible at any one time. An unknown proportion of citizens were also subject to disenfranchisement (atimia), excluding some of them permanently and others temporarily (depending on the type). Furthermore, all citizens selected were reviewed before taking up office (dokimasia) at which time they might be disqualified.

While citizens voting in the assembly were free of review or punishment, those same citizens when holding an office served the people and could be punished very severely. In addition to being subject to review prior to holding office, officeholders were also subject to an examination after leaving office (euthunai, 'straightenings' or 'submission of accounts') to review their performance. Both of these processes were in most cases brief and formulaic, but they opened up the possibility of a contest before a jury court if some citizen wanted to take a matter up.[59] In the case of scrutiny going to trial, there was the risk for the former officeholder of suffering severe penalties. Even during his period of office, any officeholder could be impeached and removed from office by the assembly. In each of the ten "main meetings" (kuriai ekklesiai) a year, the question was explicitly raised in the assembly agenda: were the office holders carrying out their duties correctly?

Citizens active as officeholders served in a quite different capacity from when they voted in the assembly or served as jurors. By and large, the power exercised by these officials was routine administration and quite limited. These officeholders were the agents of the people, not their representatives, so their role was that of administration, rather than governing. The powers of officials were precisely defined and their capacity for initiative limited. When it came to penal sanctions, no officeholder could impose a fine over fifty drachmas. Anything higher had to go before a court. Competence does not seem to have been the main issue, but rather, at least in the 4th century BC, whether they were loyal democrats or had oligarchic tendencies. Part of the ethos of democracy, rather, was the building of general competence by ongoing involvement. In the 5th century setup, the ten annually elected generals were often very prominent, but for those who had power, it lay primarily in their frequent speeches and in the respect accorded them in the assembly, rather than their vested powers.

Selection by lot

The allotment of an individual was based on citizenship, rather than merit or any form of personal popularity which could be bought. Allotment, therefore, was seen as a means to prevent the corrupt purchase of votes and it gave citizens political equality, as all had an equal chance of obtaining government office. This also acted as a check against demagoguery, though this check was imperfect and did not prevent elections from involving pandering to voters.[60]

The random assignment of responsibility to individuals who may or may not be competent has obvious risks, but the system included features meant to mitigate possible problems. Athenians selected for office served as teams (boards, panels). In a group, one person is more likely to know the right way to do things and those that do not may learn from those that do. During the period of holding a particular office, everyone on the team would be observing everybody else as a sort of check. However, there were officials, such as the nine archons, who while seemingly a board carried out very different functions from each other.

No office appointed by lot could be held twice by the same individual. The only exception was the boule or council of 500. In this case, simply by demographic necessity, an individual could serve twice in a lifetime. This principle extended down to the secretaries and undersecretaries who served as assistants to magistrates such as the archons. To the Athenians, it seems what had to be guarded against was not incompetence but any tendency to use the office as a way of accumulating ongoing power.[61]

Election

During an Athenian election, approximately one hundred officials out of a thousand were elected rather than chosen by lot. There were two main categories in this group: those required to handle large sums of money, and the 10 generals, the strategoi. One reason that financial officials were elected was that any money embezzled could be recovered from their estates; election in general strongly favoured the rich, but in this case, wealth was virtually a prerequisite.

Generals were elected not only because their role required expert knowledge, but also because they needed to be people with experience and contacts in the wider Greek world where wars were fought. In the 5th century BC, principally as seen through the figure of Pericles, the generals could be among the most powerful people in the polis. Yet in the case of Pericles, it is wrong to see his power as coming from his long series of annual generalships (each year along with nine others). His officeholding was rather an expression and a result of the influence he wielded. That influence was based on his relation with the assembly, a relation that in the first instance lay simply in the right of any citizen to stand and speak before the people. Under the 4th century version of democracy, the roles of general and of key political speaker in the assembly tended to be filled by different persons. In part, this was a consequence of the increasingly specialized forms of warfare practiced in the later period.

Elected officials, too, were subject to review before holding office and scrutiny after office. And they could also be removed from office at any time that the assembly met. There was even a death penalty for "inadequate performance" while in office.[62]

Criticism

Athenian democracy has had many critics, both ancient and modern. Ancient Greek critics of Athenian democracy include Thucydides the general and historian, Aristophanes the playwright, Plato the pupil of Socrates, Aristotle the pupil of Plato, and a writer known as the Old Oligarch. While modern critics are more likely to find fault with the restrictive qualifications for political involvement, these ancients viewed democracy as being too inclusive. For them, the common people were not necessarily the right people to rule and were likely to make huge mistakes. According to Samons:

The modern desire to look to Athens for lessons or encouragement for modern thought, government, or society must confront this strange paradox: the people that gave rise to and practiced ancient democracy left us almost nothing but criticism of this form of regime (on a philosophical or theoretical level). And what is more, the actual history of Athens in the period of its democratic government is marked by numerous failures, mistakes, and misdeeds—most infamously, the execution of Socrates—that would seem to discredit the ubiquitous modern idea that democracy leads to good government.[63]

Thucydides, from his aristocratic and historical viewpoint, reasoned that a serious flaw in democratic government was that the common people were often much too credulous about even contemporary facts to rule justly, in contrast to his own critical-historical approach to history. For example, he points to errors regarding Sparta; Athenians erroneously believed that Sparta's kings each had two votes in their ruling council and that there existed a Spartan battalion called Pitanate lochos. To Thucydides, this carelessness was due to common peoples' "preference for ready-made accounts".[64]

Similarly, Plato and Aristotle criticized democratic rule as the numerically preponderant poor tyrannizing the rich. Instead of seeing it as a fair system under which everyone has equal rights, they regarded it as manifestly unjust. In Aristotle's works, this is categorized as the difference between 'arithmetic' and 'geometric' (i.e. proportional) equality.[65]

To its ancient detractors, rule by the demos was also reckless and arbitrary. Two examples demonstrate this:

- In 406 BC, after years of defeats in the wake of the annihilation of their vast invasion force in Sicily, the Athenians at last won a naval victory at Arginusae over the Spartans. After the battle, a storm arose and the generals in command failed to collect survivors. The Athenians tried and sentenced six of the eight generals to death. Technically, it was illegal, as the generals were tried and sentenced together, rather than one by one as Athenian law required. Socrates happened to be the citizen presiding over the assembly that day and refused to cooperate (though to little effect) and stood against the idea that it was outrageous for the people to be unable to do whatever they wanted. In addition to this unlawful injustice, the demos later on regretted the decision and decided that they had been misled. Those charged with misleading the demos were put on trial, including the author of the motion to try the generals together.[66]

- In 399 BC, Socrates himself was put on trial and executed for "corrupting the young and believing in strange gods". His death gave Europe one of the first intellectual martyrs still recorded, but guaranteed the democracy an eternity of bad press at the hands of his disciple and enemy to democracy, Plato. From Socrates's arguments at his trial, Loren Samons writes, "It follows, of course, that any majority—including the majority of jurors—is unlikely to choose rightly." However, "some might argue, Athens is the only state that can claim to have produced a Socrates. Surely, some might continue, we may simply write off events such as Socrates' execution as examples of the Athenians' failure to realize fully the meaning and potential of their own democracy."[67]

While Plato blamed democracy for killing Socrates, his criticisms of the rule of the demos were much more extensive. Much of his writings were about his alternatives to democracy. His The Republic, The Statesman, and Laws contained many arguments against democratic rule and in favour of a much narrower form of government: "The organization of the city must be confided to those who possess knowledge, who alone can enable their fellow-citizens to attain virtue, and therefore excellence, by means of education."[68]

Whether the democratic failures should be seen as systemic, or as a product of the extreme conditions of the Peloponnesian war, there does seem to have been a move toward correction. A new version of democracy was established in 403 BC, but it can be linked with both earlier and subsequent reforms (graphē paranómōn 416 BC; end of assembly trials 355 BC). For instance, the system of nomothesia was introduced. In this:

A new law might be proposed by any citizen. Any proposal to modify an existing law had to be accompanied by a proposed replacement law. The citizen making the proposal had to publish it [in] advance: publication consisted of writing the proposal on a whitened board located next to the statues of the Eponymous Heroes in the agora. The proposal would be considered by the Council, and would be placed on the agenda of the Assembly in the form of a motion. If the Assembly voted in favor of the proposed change, the proposal would be referred for further consideration by a group of citizens called nomothetai (literally "establishers of the law").[18]

Increasingly, responsibility was shifted from the assembly to the courts, with laws being made by jurors and all assembly decisions becoming reviewable by courts. That is to say, the mass meeting of all citizens lost some ground to gatherings of a thousand or so which were under oath, and with more time to focus on just one matter (though never more than a day). One downside to this change was that the new democracy was less capable of responding quickly in times where quick, decisive action was needed.

Another tack of criticism is to notice the disquieting links between democracy and a number of less than appealing features of Athenian life. Although democracy predated Athenian imperialism by over thirty years, they are sometimes associated with each other. For much of the 5th century at least, democracy fed off an empire of subject states. Thucydides the son of Milesias (not the historian), an aristocrat, stood in opposition to these policies, for which he was ostracised in 443 BC.

At times the imperialist democracy acted with extreme brutality, as in the decision to execute the entire male population of Melos and sell off its women and children simply for refusing to become subjects of Athens. The common people were numerically dominant in the navy, which they used to pursue their own interests in the form of work as rowers and in the hundreds of overseas administrative positions. Furthermore, they used the income from empire to fund payment for officeholding. This is the position set out by the anti-democratic pamphlet known whose anonymous author is often called the Old Oligarch. This writer (also called pseudo-Xenophon) produced several comments critical of democracy, such as:[69]

- Democratic rule acts in the benefit of smaller self-interested factions, rather than the entire polis.

- Collectivizing political responsibility lends itself to both dishonest practices and scapegoating individuals when measures become unpopular.

- By being inclusive, opponents to the system become naturally included within the democratic framework, meaning democracy itself will generate few opponents, despite its flaws.

- A democratic Athens with an imperial policy will spread the desire for democracy outside of the polis.

- The democratic government depends on the control of resources, which requires military power and material exploitation.

- The values of freedom of equality include non-citizens more than it should.

- By blurring the distinction between the natural and political world, democracy leads the powerful to act immorally and outside their own best interest.

Aristotle also wrote about what he considered to be a better form of government than democracy. Rather than any citizen partaking with an equal share in the rule, he thought that those who were more virtuous should have greater power in governance.[70]

A case can be made that discriminatory lines came to be drawn more sharply under Athenian democracy than before or elsewhere, in particular in relation to women and slaves, as well as in the line between citizens and non-citizens. By so strongly validating one role, that of the male citizen, it has been argued that democracy compromised the status of those who did not share it.

- Originally, a male would be a citizen if his father was a citizen, Under Pericles, in 450 BC, restrictions were tightened so that a citizen had to be born to an Athenian father and an Athenian mother. So Metroxenoi, those with foreign mothers, were now to be excluded. These mixed marriages were also heavily penalized by the time of Demosthenes. Many Athenians prominent earlier in the century would have lost citizenship had this law applied to them: Cleisthenes, the founder of democracy, had a non-Athenian mother, and the mothers of Cimon and Themistocles were not Greek at all, but Thracian.[71]

- Likewise the status of women seems lower in Athens than in many Greek cities. In Sparta, women competed in public exercise – so in Aristophanes's Lysistrata the Athenian women admire the tanned, muscular bodies of their Spartan counterparts – and women could own property in their own right, as they could not at Athens. Misogyny was by no means an Athenian invention, but it has been claimed that Athens had worse misogyny than other states at the time.[72]

- Slavery was more widespread at Athens than in other Greek cities. Indeed, the extensive use of imported non-Greeks ("barbarians") as chattel slaves seems to have been an Athenian development. This triggers the paradoxical question: Was democracy "based on" slavery? It does seem clear that possession of slaves allowed even poorer Athenians — owning a few slaves was by no means equated with wealth — to devote more of their time to political life.[73] But whether democracy depended on this extra time is impossible to say. The breadth of slave ownership also meant that the leisure of the rich (the small minority who were actually free of the need to work) rested less than it would have on the exploitation of their less well-off fellow citizens. Working for wages was clearly regarded as subjection to the will of another, but at least debt servitude had been abolished at Athens (under the reforms of Solon at the start of the 6th century BC). Allowing a new kind of equality among citizens opened the way to democracy, which in turn called for a new means, chattel slavery, to at least partially equalise the availability of leisure between rich and poor. In the absence of reliable statistics, all these connections remain speculative. However, as Cornelius Castoriadis pointed out, other societies also kept slaves but did not develop democracy. Even with respect to slavery, it is speculated that Athenian fathers had originally been able to register offspring conceived with slave women for citizenship.[71]

Since the 19th century, the Athenian version of democracy has been seen by one group as a goal yet to be achieved by modern societies. They want representative democracy to be added to or even replaced by direct democracy in the Athenian way, perhaps by utilizing electronic democracy. Another group, on the other hand, considers that, since many Athenians were not allowed to participate in its government, Athenian democracy was not a democracy at all. "[C]omparisons with Athens will continue to be made as long as societies keep striving to realize democracy under modern conditions and their successes and failures are discussed."[74]

Greek philosopher and activist Takis Fotopoulos has argued that “the final failure, of Athenian democracy was not due, as it is usually asserted by its critics, to the innate contradictions of democracy itself but, on the contrary, to the fact that the Athenian democracy never matured to become an inclusive democracy. This cannot be adequately explained by simply referring to the immature ‘objective’ conditions, the low development of productive forces and so on—important as may be—because the same objective conditions prevailed at that time in many other places all over the Mediterranean, let alone the rest of Greece, but democracy flourished only in Athens” .[75]

Legacy

Since the middle of the 20th century, most countries have claimed to be democratic, regardless of the actual composition of their governments. Yet after the demise of Athenian democracy few looked upon it as a good form of government. No legitimation of that rule was formulated to counter the negative accounts of Plato and Aristotle, who saw it as the rule of the poor, who plundered the rich. Democracy came to be viewed as a "collective tyranny". "Well into the 18th century democracy was consistently condemned." Sometimes, mixed constitutions evolved with democratic elements, but "it definitely did not mean self-rule by citizens".[76]

It would be misleading to say that the tradition of Athenian democracy was an important part of the 18th-century revolutionaries' intellectual background. The classical example that inspired the American and French revolutionaries, as well as English radicals, was Rome rather than Greece, and, in the age of Cicero and Caesar, Rome was a republic but not a democracy. Thus, the Founding Fathers of the United States who met in Philadelphia in 1787 did not set up a Council of the Areopagos, but a Senate, that, eventually, met on the Capitol.[77] Following Rousseau (1712–1778), "democracy came to be associated with popular sovereignty instead of popular participation in the exercise of power".

Several German philosophers and poets took delight in what they saw as the fullness of life in ancient Athens, and not long afterwards "English liberals put forward a new argument in favor of the Athenians". In opposition, thinkers such as Samuel Johnson were worried about the ignorance of democratic decision-making bodies, but "Macaulay and John Stuart Mill and George Grote saw the great strength of the Athenian democracy in the high level of cultivation that citizens enjoyed, and called for improvements in the educational system of Britain that would make possible a shared civic consciousness parallel to that achieved by the ancient Athenians".[78]

George Grote claimed in his History of Greece (1846–1856) that "Athenian democracy was neither the tyranny of the poor, nor the rule of the mob". He argued that only by giving every citizen the vote would people ensure that the state would be run in the general interest.

Later, and until the end of World War Il, democracy became dissociated from its ancient frame of reference. After that, it was not just one of the many possible ways in which political rule could be organised. Instead, it became the only possible political system in an egalitarian society. [79]

References and sources

References

- Thorley, John (2005). Athenian Democracy. Lancaster Pamphlets in Ancient History. Routledge. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-13-479335-8.

- Raaflaub, Kurt A. (2007): The Breakthrough of Demokratia in Mid-Fifth-Century Athens, p. 112, in: Raaflaub, Kurt A.; Ober, Josiah; Wallace, Robert, eds. (2007). Origins of Democracy in Ancient Greece. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Xenophon, Anabasis 4.4.15.

- Clarke, PB. and Foweraker, Encyclopedia of Democratic Thought. Routledge, 2003, p. 196.

- Thorley, J., Athenian Democracy, Routledge, 2005, p.10.

- Farrar, C., The Origins of Democratic Thinking: The Invention of Politics in Classical Athens, CUP Archive, 25 Aug 1989, p.7.

- Encyclopædia Britannica, Areopagus.

- Farrar, C., The Origins of Democratic Thinking: The Invention of Politics in Classical Athens, CUP Archive, 25 Aug 1989, p.21.

- Thorley, J., Athenian Democracy, Routledge, 2005, p.25.

- Thorley, J., Athenian Democracy, Routledge, 2005, pp. 55–56

- Blackwell, Christopher. "The Development of Athenian Democracy". Dēmos: Classical Athenian Democracy. Stoa. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- "The Final End of Athenian Democracy".

- Habicht, C., Athens from Alexander to Antony, Harvard University Press, 1997, p. 42.

- Green, P., Alexander to Actium: The Historical Evolution of the Hellenistic Age, University of California Press, 1993, p.29.

- A Companion to Greek Studies, CUP Archive, p. 447.

- Cartledge, P, Garnsey, P. and Gruen, ES., Hellenistic Constructs: Essays in Culture, History, and Historiography, University of California Press, 1997, Ch. 5.

- Habicht, passim

- Rothchild, JA., Introduction to Athenian Democracy of the Fifth and Fourth Centuries BCE.

- Dixon, MD., Late Classical and Early Hellenistic Corinth: 338–196 BC, Routledge, 2014, p. 44.

- Kamen, D., Status in Classical Athens, Princeton University Press, 2013 p. 9.

- agathe.gr: The Unenfranchised II – Slaves and Resident Aliens

- agathe.gr: The Unenfranchised I – Women

- Thorley, J., Athenian Democracy, Routledge, 2005, p.59.

- Cohen D. and Gagarin, M., The Cambridge Companion to Ancient Greek Law Cambridge University Press, 2005, p. 278.

- Sinclair, RK.,Democracy and Participation in Athens, Cambridge University Press, 30 Aug 1991, pp. 25–26.

- Thorley, J., Athenian Democracy, Routledge, 2005, p.32.

- Thorley, J., Athenian Democracy, Routledge, 2005, p.57.

- Thorley, J., Athenian Democracy, Routledge, 2005, p 33–34.

- Manville, PB., The Origins of Citizenship in Ancient Athens, Princeton University Press, 2014 p. 182.

- Aristophanes Acharnians 17–22.

- Aristoph. Ekklesiazousai 378-9

- Terry Buckley, Aspects of Greek History: A Source-Based Approach, Routledge, 2006, p. 98.

- Encyclopædia Britannica: boule.

- Thorley, J., Athenian Democracy, Routledge, 2005, pp. 31–32

- Thorley, J., Athenian Democracy, Routledge, 2005, pp. 30–31.

- Hignett, History of the Athenian Constitution, 238

- Hignett, History of the Athenian Constitution, 241

- Dover, KJ., Greek Popular Morality in the Time of Plato and Aristotle, Hackett Publishing, 1994, p.23.

- Thorley, J., Athenian Democracy, Routledge, 2005, pp. 36–38.

- MacDowell, DM., The Law in Classical Athens, Cornell University Press, 1978, p.36.

- Bertoch, MJ., The Greeks had a jury for it, ABA Journal, October, 1971, Vol. 57, p.1013.

- Arnason, JP., Raaflaub, KA. and Wagner, P., The Greek Polis and the Invention of Democracy: A Politico-cultural Transformation and Its Interpretations, John Wiley & Sons, 2013' p. 167.

- Rhodes, PJ., A History of the Classical Greek World: 478 – 323 BC, John Wiley & Sons, 2011, p. 235.

- MacDowell, DM., The Law in Classical Athens, Cornell University Press, 1978, p.250.

- Thorley, J., Athenian Democracy, Routledge, 2005, p.60.

- Cohen D. and Gagarin, M., The Cambridge Companion to Ancient Greek Law Cambridge University Press, 2005, p. 130.

- "Funeral Oration", Thucydides II.40, trans. Rex Warner (1954).

- Goldhill, S., 2004, The Good Citizen, in Love, Sex & Tragedy: Why Classics Matters. John Murray, London, 179-94.

- Anthamatten, Eric (12 June 2017). "Trump and the True Meaning of 'Idiot'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- Parker, Walter C. (January 2005). "Teaching Against Idiocy". 86 (5). Bloomington: Phi Delta Kappa: 344. ERIC EJ709337. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Sparkes, A.W. (1988). "Idiots, Ancient and Modern". Australian Journal of Political Science. 23 (1): 101–102. doi:10.1080/00323268808402051.

- see Idiot#Etymology

- Benn, Stanley (2006). "Democracy". In Borchert, Donald M. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2 (2nd ed.). Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA. pp. 699–703 – via Gale Virtual Reference Library.

- Thorley, J., Athenian Democracy, Routledge, 2005, pp. 8–9.

- Sinclair, RK., Democracy and Participation in Athens, Cambridge University Press, 30 Aug 1991, pp. 1–2.

- Encyclopædia Britannica: archon

- Thorley, J., Athenian Democracy, Routledge, 2005, p. 55.

- Thorley, J., Athenian Democracy, Routledge, 2005, p.29.

- Thorley, J., Athenian Democracy, Routledge, 2005, pp. 42–43.

- Samons, L., What's Wrong with Democracy?: From Athenian Practice to American Worship, University of California Press, 2004, pp. 44–45.

- Raaflaub, Kurt A., Ober, Josiah and Wallace Robert W., Origins of Democracy in Ancient Greece, University of California Press, 2007 p. 182.

- Cartledge, Paul (July 2006). "Ostracism: selection and de-selection in ancient Greece". History & Policy. United Kingdom: History & Policy. Archived from the original on 16 April 2010. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- Samons, L., What's Wrong with Democracy?: From Athenian Practice to American Worship, University of California Press, 2004, p. 6.

- Ober, J., Political Dissent in Democratic Athens: Intellectual Critics of Popular Rule, Princeton University Press, 2001, pp. 54 & 78–79.

- Kagan, D., https://books.google.com/books?id=z9garz74CJ0C&dq=athens+kagan&q=%22Plato+and+Aristotle+must%22#v=snippet&q=%22Plato%20and%20Aristotle%20must%22&f=false The Fall of the Athenian Empire, Cornell University Press, 2013, p. 108.]

- Hobden, F. and Tuplin, C., Xenophon: Ethical Principles and Historical Enquiry, BRILL, 2012, pp. 196–199.

- Samons, L., What's Wrong with Democracy?: From Athenian Practice to American Worship, University of California Press, 2004, p. 12 & 195.

- Beck, H., Companion to Ancient Greek Government, John Wiley & Sons, 2013, p. 103.

- Ober, J., Political Dissent in Democratic Athens: Intellectual Critics of Popular Rule, Princeton University Press, 2001, p. 43.

- Beck, H., Companion to Ancient Greek Government, John Wiley & Sons, 2013, p.107.

- Hansen, MH., The Athenian Democracy in the Age of Demosthenes: Structure, Principles, and Ideology, University of Oklahoma Press, 1991, p.53.

- Just, R., Women in Athenian Law and Life, Routledge, 2008, p. 15.

- Rodriguez, JP., The Historical Encyclopedia of World Slavery, Volume 7, ABC-CLIO, 1997, pp. 312–314.

- Grafton, A., Most, GA. and Settis, S., The Classical Tradition, Harvard University Press, 2010, p.259.

- Fotopoulos Takis, Towards An Inclusive Democracy, Cassell/Continuum, 1997, p.194"

- Grafton, A., Most, G.A. and Settis, S., The Classical Tradition, Harvard University Press, 2010, pp. 256–259.

- Hansen, M.H., The Tradition of Ancient Greek Democracy and Its Importance for Modern Democracy, Kgl. Danske Videnskabernes Selskab, 2005, p. 10.

- Roberts, J., in Euben, J.P., et al., Athenian Political Thought and the Reconstruction of American Democracy', Cornell University Press, 1994, p. 96.

- Vlassopoulos, K., Politics Antiquity and Its Legacy, Oxford University Press, 2009.

Sources

- Habicht, Christian (1997). Athens from Alexander to Antony. Harvard. ISBN 0-674-05111-4.

- Hansen, M.H. (1987). The Athenian Democracy in the age of Demosthenes. Oxford. ISBN 978-0-8061-3143-6.

- Hignett, Charles (1962). A History of the Athenian Constitution. Oxford. ISBN 0-19-814213-7.

- Manville, B.; Ober, Josiah (2003). A company of citizens : what the world's first democracy teaches leaders about creating great organizations. Boston.

- Meier C. 1998, Athens: a portrait of the city in its Golden Age (translated by R. and R. Kimber). New York

- Ober, Josiah (1989). Mass and Elite in Democratic Athens: Rhetoric, Ideology and the Power of the People. Princeton.

- Ober, Josiah; Hendrick, C. (1996). Demokratia: a conversation on democracies, ancient and modern. Princeton.

- Rhodes, P.J. (2004). Athenian democracy. Edinburgh.

- Sinclair, R. K. (1988). Democracy and Participation in Athens. Cambridge University Press.

External links

- Ancient History Encyclopedia – Athenian Democracy

- Ewbank, N. The Nature of Athenian Democracy, Clio History Journal, 2009.