Amantadine

Amantadine, sold under the brand name Gocovri among others, is a medication used to treat dyskinesia associated with parkinsonism and influenza caused by type A influenzavirus, though its use for the latter is no longer recommended due to drug resistance.[3][4] It acts as a nicotinic antagonist and noncompetitive NMDA antagonist.[5][6] The antiviral mechanism of action is antagonism of the influenzavirus A M2 proton channel, which prevents viral shedding.[5]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Gocovri, Symadine, Symmetrel, others |

| Other names | 1-Adamantylamine |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682064 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 86–90%[1] |

| Protein binding | 67%[1] |

| Metabolism | Minimal (mostly to acetyl metabolites)[1] |

| Elimination half-life | 10–31 hours[1] |

| Excretion | Urine[1] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.011.092 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C10H17N |

| Molar mass | 151.253 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

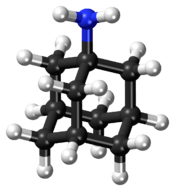

Chemical structure

Amantadine (brand names Gocovri, Symadine, and Symmetrel[6][7]) is the organic compound 1-adamantylamine or 1-aminoadamantane, which consists of an adamantane backbone with an amino group substituted at one of the four methyne positions.[8][9] Rimantadine is a closely related adamantane derivative with similar biological properties;[10] both target the M2 proton channel of influenza A virus.[5]

Medical uses

Parkinson's disease

Amantadine is used to treat Parkinson's disease-related dyskinesia and drug-induced parkinsonism syndromes.[8] Amantadine may be used alone or combined with another anti-parkinson or anticholinergic drug.[5] The specific symptoms targeted by amantadine therapy are dyskinesia and rigidity. Levodopa and amantadine is a common combination.[5][9]

A 2003 Cochrane review concluded evidence inadequately proved the safety or efficacy of amantadine to treat dyskinesia.[11]

The World Health Organization in 2008, reported amantadine is not effective as a stand-alone parkinsonian therapy. Amantadine was recommended for combination therapy with levodopa.[12]

Influenza A

Amantadine is no longer recommended for treatment or prophylaxis of influenza A in the United States.[3] Amantadine has no effect preventing or treating influenza B infections.[3] The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found 100% of seasonal H3N2 and 2009 pandemic flu samples were resistant to adamantanes (amantadine and rimantidine) during the 2008–2009 flu season.[5][13]

The CDC guidelines updated to recommend only neuraminidase inhibitors for influenza treatment and prophylaxis. The CDC currently recommends against amantadine and rimantadine to treat influenza A infections.[3]

Similarly, the 2011 World Health Organization virology report showed all tested H1N1 influenza A viruses were resistant to amantadine.[4] Current WHO guidelines recommend against use of M2 inhibitors for influenza A. The continued high rate of resistance observed in laboratory testing of influenza A has reduced the priority of M2 resistance testing until further notice.

A 2014 Cochrane review did not find evidence for efficacy or safety of amantadine used for the prevention or treatment of influenza A.[14]

Extra-pyramidal side effects

An extended release formulation is used to treat dyskinesia, a side effect of levodopa which is taken by people who have Parkinson's disease.[15] WHO recommendations are for amantadine as a combination therapy to reduce levodopa side effects.[12]

Off-label uses

Fatigue in multiple sclerosis

Amantadine also seems to have moderate effects on multiple sclerosis (MS) related fatigue.[16]

Awareness and consciousness in patients in a vegetative state

Awakening with amantadine from a persistent vegetative state after subarachnoid haemorrhage

In one case, a 36-year-old woman had a subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) and was in a persistent vegetative state. Under a treatment of amantadine, and nine months after the disease onset, the patient improved 5 points on the coma recovery scale, and was able to communicate adequately in two to six-word sentences.[17]

Contraindications

Amantadine is contraindicated in persons with end stage renal disease.[15] The drug is renally cleared.[6][18][19]

Live attenuated vaccines are contraindicated while taking amantadine.[15] It is possible that amantadine will inhibit viral replication and reduce the efficacy of administered vaccines. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommends avoiding live vaccination and amantadine for two weeks prior to vaccine administration or 48 hours afterwards.[18]

Adverse effects

Amantadine has been associated with several central nervous system (CNS) side effects. About 10% or more of patients may experience falls, dizziness, and hallucinations. Other side effects may include constipation or dry mouth.[15]

Serious side effects may include drowsiness (especially while driving), suicidal thoughts, actions, or depression, new or worsened hallucinations, inhibited actions (gambling, sexual activity, spending, other addictions) and diminished control over compulsions, and light headedness, falls, and hypotension (low blood pressure).[15]

Rare cases of severe skin rashes, such as Stevens–Johnson syndrome,[20] and of suicidal ideation have also been reported in patients treated with amantadine.[19][21]

Livedo reticularis is a rare possible side effect of amantadine use for Parkinson's disease.[22]

Mechanism of action

Parkinson's disease

The mechanism of its antiparkinsonian effect is poorly understood.[23] Amantadine appears to be a weak antagonist of the NMDA-type glutamate receptor, increases dopamine release, and blocks dopamine reuptake.[24][25][26] Amantadine probably does not inhibit monoamine oxidase (MAO) enzyme.[27] Moreover, the drug has many effects in the brain, including release of dopamine and norepinephrine from nerve endings. It appears to be an anticholinergic (specifically at alpha-7 nicotinic receptors) like the similar pharmaceutical memantine.

In 2004, it was discovered that amantadine and memantine bind to and act as agonists of the σ1 receptor (Ki = 7.44 μM and 2.60 μM, respectively), and that activation of the σ1 receptor is involved in the dopaminergic effects of amantadine at therapeutically relevant concentrations.[28] These findings may also extend to the other adamantanes such as adapromine, rimantadine, and bromantane, and could explain the psychostimulant-like effects of this family of compounds.[28]

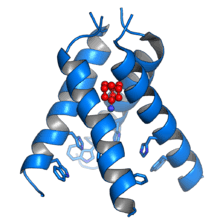

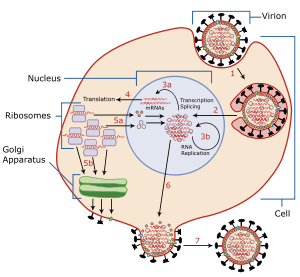

Influenza

The mechanisms for amantadine's antiviral and antiparkinsonian effects are unrelated.[6][18] Amantadine targets the influenza A M2 ion channel protein. The M2 protein's function is to allow the intracellular virus to replicate (M2 also functions as a proton channel for hydrogen ions to cross into the vesicle), and exocytose newly formed viral proteins to the extracellular space (viral shedding). By blocking the M2 channel, the virus is unable to replicate because of impaired replication, protein synthesis, and exocytosis.[30]

Amantadine and rimantadine function in a mechanistically identical fashion, entering the barrel of the tetrameric M2 channel and blocking pore function—i.e., proton translocation.[5]

Resistance to the drug class is a consequence of mutations to the pore-lining residues of the channel, preventing both amantadine and rimantadine from inhibiting the channel in their usual way.

Influenza B strains possess a structurally distinct M2 channel with channel-facing side chains that fully obstruct the channel vis-à-vis binding of adamantine-class channel inhibitors, while still allowing proton flow and channel function to occur; this constriction in the channels is responsible for the ineffectiveness of this drug and rimantadine towards all circulating Influenza B strains.

Interactions

Amantadine may affect the central nervous system due to dopaminergic and anticholinergic properties. The mechanisms of action are not fully known. Because of the CNS effects, caution is required when prescribing additional CNS stimulants or anticholinergic drugs.[18]

Certain drugs increase the chances of déjà vu occurring in the user, resulting in a strong sensation that an event or experience currently being experienced has already been experienced in the past. Some pharmaceutical drugs, when taken together, have also been implicated in the cause of déjà vu. Taiminen and Jääskeläinen (2001)[31] reported the case of an otherwise healthy male who started experiencing intense and recurrent sensations of déjà vu upon taking the drugs amantadine and phenylpropanolamine together to relieve flu symptoms. He found the experience so interesting that he completed the full course of his treatment and reported it to the psychologists to write up as a case study. Because of the dopaminergic action of the drugs and previous findings from electrode stimulation of the brain (e.g. Bancaud, Brunet-Bourgin, Chauvel, & Halgren, 1994),[32] Taiminen and Jääskeläinen speculate that déjà vu occurs as a result of hyperdopaminergic action in the mesial temporal areas of the brain.

History

It was first used in the FRG in 1966. Amantadine was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in October 1968, as a prophylactic agent against Asian influenza.[33][15] Amantadine trial experiments exposed volunteer college students to a viral challenge. The group that received amantadine (100 milligrams 18 hours before viral challenge) had less Asia influenza infections than the placebo group.[33] Amantadine received approval for the treatment of influenza virus A[34][35][36][37] in adults in 1976.[33]

An incidental finding in 1969 prompted investigations about amantadine's effectiveness for treating symptoms of Parkinson's disease.[33] A woman with Parkinson's disease was prescribed amantadine to treat her influenza infection and reported her cogwheel rigidity and tremors improved. She also reported that her symptoms worsened after she finished the course of amantadine.[33] The published case report was not initially corroborated by any other instances by the medical literature or manufacturer data. A team of researchers looked at a group of ten patients with Parkinson's disease and gave them amantadine. Seven of the ten patients showed improvement, which was convincing evidence for the need of a clinical trial. The 1969 trial (lead author Robert S. Schwab, MD) included 163 patients with Parkinson's disease and 66% experienced subjective or objective reduction of symptoms.[33][38] Additional studies from Schwab's team followed patients for greater lengths of time and in different combinations of neurological drugs.[39] The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved amantadine for use in the treatment of Parkinson's disease.[18][33]

In 2017, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the use of amantadine in an extended release formulation developed by Adamas Pharma for the treatment of dyskinesia, an adverse effect of levodopa, that people with Parkinson's experience.[40][41]

Veterinary misuse

In 2005, Chinese poultry farmers were reported to have used amantadine to protect birds against avian influenza.[42] In Western countries and according to international livestock regulations, amantadine is approved only for use in humans. Chickens in China have received an estimated 2.6 billion doses of amantadine.[42] Avian flu (H5N1) strains in China and southeast Asia are now resistant to amantadine, although strains circulating elsewhere still seem to be sensitive. If amantadine-resistant strains of the virus spread, the drugs of choice in an avian flu outbreak will probably be restricted to neuraminidase inhibitors oseltamivir and zanamivir which block the action of viral neuraminidase enzyme on the surface of influenza virus particles.[43] However, there is an increasing incidence of oseltamivir resistance in circulating influenza strains (e.g., H1N1), highlighting the serious need for the development of new anti-influenza therapies.[44]

In September 2015, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration announced the recall of Dingo Chip Twists "Chicken in the Middle" dog treats because the product has the potential to be contaminated with amantadine.[45]

References

- "Symmetrel (amantadine hydrochloride)" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Australia Pty Limited. 29 June 2011. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- "Trilasym 50 mg/ 5 ml Oral Solution - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 24 September 2019. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- "Influenza Antiviral Medications: Summary for Clinicians". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 17 April 2019. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- "WHO | Summary of influenza antiviral susceptibility surveillance findings". WHO. September 2011 – March 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- Golan DE, Armstrong EJ, Armstrong AW (2017). Principles of pharmacology: the pathophysiologic basis of drug therapy (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer. pp. 142, 199, 205t, 224t, 608, 698–700. ISBN 9781451191004. OCLC 914593652.

- "Australian Product Information – Symmetrel (Amantadine Hydrochloride) Capsules". Australian Department of Health Therapeutic Goods Administration. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- "Amantadine: MedlinePlus Drug Information". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- "Amantadine". www.drugbank.ca. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- "Amantadine - an overview". ScienceDirect. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- "Rimantadine hydrochloride (CHEBI:8865)". www.ebi.ac.uk. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- Crosby NJ, Deane KH, Clarke CE, et al. (Cochrane Movement Disorders Group) (22 April 2003). "Amantadine for dyskinesia in Parkinson's disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD003467. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003467. PMID 12804468.

- World Health Organization (2009). Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR (eds.). WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. p. 242. hdl:10665/44053. ISBN 978-9241547659.

- CDC weekly influenza report – week 35, cdc.gov

- Alves Galvão MG, Rocha Crispino Santos MA, Alves da Cunha AJ, et al. (Cochrane Acute Respiratory Infections Group) (November 2014). "Amantadine and rimantadine for influenza A in children and the elderly". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (11): CD002745. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002745.pub4. PMID 25415374.

- "Gocovri- amantadine capsule, coated pellets". DailyMed. 26 December 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- Braley TJ, Chervin RD (August 2010). "Fatigue in multiple sclerosis: mechanisms, evaluation, and treatment". Sleep. 33 (8): 1061–67. doi:10.1093/sleep/33.8.1061. PMC 2910465. PMID 20815187.

- https://casereports.bmj.com/content/2017/bcr-2017-220305#ref-8

- "Symmetrel (Amantadine Hydrochloride, USP) fact sheet" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- "Symmetrel (Amantadine) Prescribing Information" (PDF). Endo Pharmaceuticals. May 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 November 2014. Retrieved 2 August 2007. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Singhal KC, Rahman SZ (2002). "Stevens Johnson Syndrome Induced by Amantadine". Rational Drug Bulletin. 12 (1): 6.

- Cook PE, Dermer SW, McGurk T (November 1986). "Fatal overdose with amantadine". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 31 (8): 757–58. doi:10.1177/070674378603100814. PMID 3791133.

- Vollum DI, Parkes JD, Doyle D (June 1971). "Livedo reticularis during amantadine treatment". British Medical Journal. 2 (5762): 627–28. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.5762.627. PMC 1796527. PMID 5580722.

- "Amantadine – MeSH". NCBI.

- Jasek, W, ed. (2007). Austria-Codex (in German) (62nd ed.). Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag. p. 3962. ISBN 978-3-85200-181-4.

- Kornhuber J, Bormann J, Hübers M, Rusche K, Riederer P (April 1991). "Effects of the 1-amino-adamantanes at the MK-801-binding site of the NMDA-receptor-gated ion channel: a human postmortem brain study". European Journal of Pharmacology. 206 (4): 297–300. doi:10.1016/0922-4106(91)90113-v. PMID 1717296.

- Blanpied TA, Clarke RJ, Johnson JW (March 2005). "Amantadine inhibits NMDA receptors by accelerating channel closure during channel block". The Journal of Neuroscience. 25 (13): 3312–22. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4262-04.2005. PMC 6724906. PMID 15800186.

- Strömberg U, Svensson TH (November 1971). "Further studies on the mode of action of amantadine". Acta Pharmacologica et Toxicologica. 30 (3): 161–71. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0773.1971.tb00646.x. PMID 5171936.

- Peeters M, Romieu P, Maurice T, Su TP, Maloteaux JM, Hermans E (April 2004). "Involvement of the sigma 1 receptor in the modulation of dopaminergic transmission by amantadine". The European Journal of Neuroscience. 19 (8): 2212–20. doi:10.1111/j.0953-816X.2004.03297.x. PMID 15090047.

- Thomaston JL, Alfonso-Prieto M, Woldeyes RA, Fraser JS, Klein ML, Fiorin G, DeGrado WF (November 2015). "High-resolution structures of the M2 channel from influenza A virus reveal dynamic pathways for proton stabilization and transduction". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 112 (46): 14260–65. Bibcode:2015PNAS..11214260T. doi:10.1073/pnas.1518493112. PMC 4655559. PMID 26578770.

- PubChem. "Amantadine". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- Taiminen, T.; Jääskeläinen, S. (2001). "Intense and recurrent déjà vu experiences related to amantadine and phenylpropanolamine in a healthy male". Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 8 (5): 460–462. doi:10.1054/jocn.2000.0810. PMID 11535020.

- Bancaud, J.; Brunet-Bourgin, F.; Chauvel, P.; Halgren, E. (1994). "Anatomical origin of déjà vu and vivid 'memories' in human temporal lobe epilepsy". Brain : A Journal of Neurology. 117 (1): 71–90. doi:10.1093/brain/117.1.71. PMID 8149215.

- Okun, M. S.; Haider, M.; Hubsher, G. (3 April 2012). "Amantadine: The journey from fighting flu to treating Parkinson disease". Neurology. 78 (14): 1096–1099. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e31824e8f0d. ISSN 0028-3878. PMID 22474298.

- Hounshell DA, Kenly Smith J (1988). Science and Corporate Strategy: Du Pont R&D, 1902–1980. Cambridge University Press. p. 469. ISBN 978-0521327671.

- "Sales of flu drug by du Pont unit a 'disappointment'". The New York Times. Wilmington, Delaware. 5 October 1982. Retrieved 19 May 2008.

- Maugh TH (November 1979). "Panel urges wide use of antiviral drug". Science. 206 (4422): 1058–60. Bibcode:1979Sci...206.1058M. doi:10.1126/science.386515. PMID 386515.

- Maugh TH (April 1976). "Amantadine: an alternative for prevention of influenza". Science. 192 (4235): 130–31. doi:10.1126/science.192.4235.130. PMID 17792438.

- Schwab, Robert S. (19 May 1969). "Amantadine in the Treatment of Parkinson's Disease". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 208 (7): 1168. doi:10.1001/jama.1969.03160070046011. ISSN 0098-7484.

- Schwab, R. S. (13 November 1972). "Amantadine in Parkinson's disease. Review of more than two years' experience". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 222 (7): 792–795. doi:10.1001/jama.222.7.792. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 4677928.

- Bastings E. "NDA 208944 Approval Letter" (PDF).

- "Drug Approval Package: Gocovri (amantadine extended-release)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 29 June 2018. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- Sipress A (18 June 2005). "Bird Flu Drug Rendered Useless". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2 August 2007.

- Kumar B, Asha K, Khanna M, Ronsard L, Meseko CA, Sanicas M (April 2018). "The emerging influenza virus threat: status and new prospects for its therapy and control". Archives of Virology. 163 (4): 831–44. doi:10.1007/s00705-018-3708-y. PMC 7087104. PMID 29322273.

- Aoki FY, Boivin G, Roberts N (2007). "Influenza virus susceptibility and resistance to oseltamivir". Antiviral Therapy. 12 (4 Pt B): 603–16. PMID 17944268.

- "Enforcement Report – Week of September 23, 2015". FDA.gov. U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

External links

- "Amantadine". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.