1957–1958 influenza pandemic

The 1957–1958 influenza pandemic, also known as the Asian flu, was a global pandemic of influenza A virus subtype H2N2 that originated in Guizhou, China, and killed at least a million people worldwide.

| Influenza (Flu) |

|---|

|

|

History

The strain of virus that caused the pandemic, influenza A virus subtype H2N2, was a recombination of avian influenza (probably from geese) and human influenza viruses.[1][2] As it was a novel strain of the virus, the population had minimal immunity.[1][3]

The first cases were reported in Guizhou in late 1956[1] or early 1957,[4][5][6] and they were reported in the neighbouring province of Yunnan before the end of February.[7] On 17 April, The Times reported that "an influenza epidemic has affected thousands of Hong Kong residents".[3] By the end of the month, Singapore also experienced an outbreak of the new flu, which peaked in mid-May with 680 deaths.[8] In Taiwan, 100,000 were affected by mid-May, and India suffered a million cases by June. In late June, the pandemic reached the United Kingdom.[3]

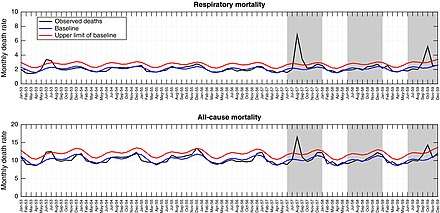

By June 1957, it reached the United States, where it initially caused few infections.[2] Some of the first people affected were US Navy personnel at destroyers docked at Newport Naval Station and new military recruits elsewhere.[9] The first wave peaked in October and affected mainly children who recently returned to school after summer break. The second wave, in January and February 1958, was more pronounced among elderly people and so was more fatal.[2][10]

The microbiologist Maurice Hilleman was alarmed by pictures of those affected by the virus in Hong Kong that were published in The New York Times. He obtained samples of the virus from a US Navy doctor in Japan. The Public Health Service released the virus cultures to vaccine manufacturers on 12 May 1957, and a vaccine entered trials at Fort Ord on 26 July and Lowry Air Force Base on 29 July.[9]

The number of deaths peaked the week ending 17 October, with 600 reported in England and Wales. The vaccine was available in the same month in the United Kingdom.[3] Although it was initially available only in limited quantities,[10][3] its rapid deployment helped contain the pandemic.[2]

H2N2 influenza virus continued to transmit until 1968, when it transformed via antigenic shift into influenza A virus subtype H3N2, the cause of the 1968 influenza pandemic.[2][11]

Mortality estimates

The case fatality rate of Asian flu was approximately 0.67%.[12] The disease was estimated to have a 3% rate of complications and 0.3% mortality in the United Kingdom;[3] it could cause pneumonia by itself without the presence of secondary bacterial infection. It may have infected as many as or more people than the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic, but the vaccine, improved health care, and the invention of antibiotics to manage opportunistic bacterial infections contributed to a lower mortality rate.[1] Estimates of the number of deaths worldwide vary, with the UK government estimating between one and four million and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimating 1.1 million.[1][2][13][14][15] According to a study in the Journal of Infectious Diseases, the highest excess mortality occurred in Latin America.[16] About 70,000 to 116,000 people died in the United States, and an estimated 33,000 deaths in the United Kingdom were attributed to the 1957–58 flu outbreak.[1][11][13][17] It caused many infections in children, spread in schools, and led to many school closures. However, the virus was rarely fatal in children and was most deadly in pregnant women, the elderly, and those with pre-existing heart and lung disease.[1] In Germany, around 30,000 people died of the flu between September 1957 and April 1958.[18]

Economic effects

The Dow Jones Industrial Average lost 15% of its value in the second half of 1957.[17] In the United Kingdom, the government paid out £10,000,000 in sickness benefit, and some factories and mines had to close.[3] Many schools had to close in Ireland, including seventeen in Dublin.[19]

References

- Clark, William R. (2008). Bracing for Armageddon?: The Science and Politics of Bioterrorism in America. Oxford University Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-19-045062-5.

- "1957 flu pandemic". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- Jackson, Claire (1 August 2009). "History lessons: the Asian Flu pandemic". British Journal of General Practice. 59 (565): 622–623. doi:10.3399/bjgp09X453882. PMC 2714797. PMID 22751248.

- Peckham, Robert (2016). Epidemics in Modern Asia. Cambridge University Press. p. 276. ISBN 978-1-107-08468-1.

- Pennington, T H (2006). "A slippery disease: a microbiologist's view". BMJ. 332 (7544): 789–790. doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7544.789. PMC 1420718. PMID 16575087.

- Tsui, Stephen KW (2012). "Some observations on the evolution and new improvement of Chinese guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of influenza". Journal of Thoracic Disease. 4 (1): 7–9. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2011.11.03. ISSN 2072-1439. PMC 3256544. PMID 22295158.

- Strahan, Lachlan M. (October 1994). "An oriental scourge: Australia and the Asian flu epidemic of 1957". Australian Historical Studies. 26 (103): 182–201. doi:10.1080/10314619408595959.

- Ho, Olivia (19 April 2020). "Three times that the world coughed, and Singapore caught the bug". Straits Times. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- Zeldovich, Lina (7 April 2020). "How America Brought the 1957 Influenza Pandemic to a Halt". JSTOR Daily. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- "Definition of Asian flu". MedicineNet. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- "Pandemic flu virus from 1957 mistakenly sent to labs". CIDRAP. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- Nickol, Michaela E.; Kindrachuk, Jason (2019-02-06). "A year of terror and a century of reflection: perspectives on the great influenza pandemic of 1918–1919". BMC Infectious Diseases. 19 (1): 117. doi:10.1186/s12879-019-3750-8. ISSN 1471-2334. PMC 6364422. PMID 30727970.

- "Coronavirus: action plan. A guide to what you can expect across the UK" (PDF). gov.uk. 3 March 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- "Overarching Government Strategy to Respond to Pandemic Influenza. Analysis of the Scientific Evidence Base" (PDF). gov.uk. November 2007. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- "1957-1958 Pandemic (H2N2 virus)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 22 January 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- Viboud, Cécile; Simonsen, Lone; Fuentes, Rodrigo; Flores, Jose; Miller, Mark A.; Chowell, Gerardo (4 February 2016). "Global Mortality Impact of the 1957–1959 Influenza Pandemic". Journal of Infectious Diseases. 213 (5): 738–745. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiv534. PMC 4747626. PMID 26908781.

- Pinsker, Joe (28 February 2020). "How to Think About the Plummeting Stock Market". The Atlantic. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

Perhaps a better parallel is the flu pandemic of 1957 and ’58, which originated in East Asia and killed at least 1 million people, including an estimated 116,000 in the U.S. In the second half of 1957, the Dow fell about 15 percent. "Other things happened over that time period" too, Wald notes, but "at least there was no world war."

- Kutzner, Maximilian (19 May 2020). "Debatte zur Herkunft der Asiatischen Grippe 1957" [Debate on the origin of the Asian flu of 1957]. Deutschland Archiv (in German). Federal Agency for Civic Education. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- Mullally, Una. "An 'Asian flu' pandemic closed 17 Dublin schools in 1957". The Irish Times. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

Sources

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 1957–1958 influenza pandemic. |

- Chowell, Gerardo; Simonsen, Lone; Fuentes, Rodrigo; Flores, Jose; Miller, Mark A.; Viboud, Cécile (May 2017). "Severe mortality impact of the 1957 influenza pandemic in Chile". Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses. 11 (3): 230–239. doi:10.1111/irv.12439. PMC 5410718. PMID 27883281.

- Cobos, April J.; Nelson, Clinton G.; Jehn, Megan; Viboud, Cécile; Chowell, Gerardo (2016). "Mortality and transmissibility patterns of the 1957 influenza pandemic in Maricopa County, Arizona". BMC Infectious Diseases. 16 (1): 405. doi:10.1186/s12879-016-1716-7. ISSN 1471-2334. PMC 4982429. PMID 27516082.