Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev[lower-alpha 2] (Russian: Михаи́л Серге́евич Горбачёв; born 2 March 1931) is a Russian and former Soviet politician. The eighth and last leader of the Soviet Union, he was the general secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1985 until 1991. He was also the country's head of state from 1988 until 1991, serving as the chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet from 1988 to 1989, chairman of the Supreme Soviet from 1989 to 1990, and president of the Soviet Union from 1990 to 1991. Ideologically, he initially adhered to Marxism–Leninism although by the early 1990s had moved toward social democracy.

Mikhail Gorbachev | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Михаи́л Горбачёв | |||||||||||||||||||||

.png) Gorbachev in 1986 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| President of the Soviet Union | |||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 15 March 1990 – 19 August 1991[lower-alpha 1] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Vice President | Gennady Yanayev | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Office established (partly himself as Chairman of the Supreme Soviet) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by |

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union | |||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 11 March 1985 – 24 August 1991 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Deputy | Vladimir Ivashko | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Konstantin Chernenko | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Vladimir Ivashko (acting) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union | |||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 25 May 1989 – 15 March 1990 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Deputy | Anatoly Lukyanov | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Himself as Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Anatoly Lukyanov | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union | |||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 1 October 1988 – 25 May 1989 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Andrei Gromyko | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Himself as Chairman of the Supreme Soviet | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev 2 March 1931 Privolnoye, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Nationality |

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | Union of Social Democrats (2007–present) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Other political affiliations |

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse(s) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Irina Virganskaya | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | Moscow State University | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Awards | Nobel Peace Prize | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | Official website | ||||||||||||||||||||

Central institution membership

Other offices held

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Of mixed Russian and Ukrainian heritage, Gorbachev was born in Privolnoye, Stavropol Krai, to a poor peasant family. Growing up under the rule of Joseph Stalin, in his youth he operated combine harvesters on a collective farm before joining the Communist Party, which then governed the Soviet Union as a one-party state according to Marxist-Leninist doctrine. While studying at Moscow State University, he married fellow student Raisa Titarenko in 1953 prior to receiving his law degree in 1955. Moving to Stavropol, he worked for the Komsomol youth organization and, after Stalin's death, became a keen proponent of the de-Stalinization reforms of Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev. He was appointed the First Party Secretary of the Stavropol Regional Committee in 1970, in which position he oversaw construction of the Great Stavropol Canal. In 1978 he returned to Moscow to become a Secretary of the party's Central Committee and in 1979 joined its governing Politburo. Within three years of the death of Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev, following the brief regimes of Yuri Andropov and Konstantin Chernenko, the Politburo elected Gorbachev as General Secretary, the de facto head of government, in 1985.

Although committed to preserving the Soviet state and to its socialist ideals, Gorbachev believed significant reform was necessary, particularly after the 1986 Chernobyl disaster. He withdrew from the Soviet–Afghan War and embarked on summits with United States President Ronald Reagan to limit nuclear weapons and end the Cold War. Domestically, his policy of glasnost ("openness") allowed for enhanced freedom of speech and press, while his perestroika ("restructuring") sought to decentralize economic decision making to improve efficiency. His democratization measures and formation of the elected Congress of People's Deputies undermined the one-party state. Gorbachev declined to intervene militarily when various Eastern Bloc countries abandoned Marxist-Leninist governance in 1989–90. Internally, growing nationalist sentiment threatened to break up the Soviet Union, leading Marxist-Leninist hardliners to launch the unsuccessful August Coup against Gorbachev in 1991. In the wake of this, the Soviet Union dissolved against Gorbachev's wishes and he resigned. After leaving office, he launched his Gorbachev Foundation, became a vocal critic of Russian Presidents Boris Yeltsin and Vladimir Putin, and campaigned for Russia's social-democratic movement.

Widely considered one of the most significant figures of the second half of the 20th century, Gorbachev remains the subject of controversy. The recipient of a wide range of awards—including the Nobel Peace Prize—he was widely praised for his pivotal role in ending the Cold War, curtailing human rights abuses in the Soviet Union, and tolerating both the fall of Marxist–Leninist administrations in eastern and central Europe and the reunification of Germany. Conversely, in Russia he is often derided for not stopping the Soviet collapse, an event which brought a decline in Russia's global influence and precipitated an economic crisis.

Early life

Childhood: 1931–1950

Gorbachev was born on 2 March 1931 in the village of Privolnoye, Stavropol Krai, then in the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, one of the constituent republics of the Soviet Union.[4] At the time, Privolnoye was divided almost evenly between ethnic Russians and ethnic Ukrainians.[5] Gorbachev's paternal family were ethnic Russians and had moved to the region from Voronezh several generations before; his maternal family were of ethnic Ukrainian heritage and had migrated from Chernigov.[6] His parents named him Victor, but at the insistence of his mother—a devout Orthodox Christian—he had a secret baptism, where his grandfather christened him Mikhail.[7] His relationship with his father, Sergey Andreyevich Gorbachev, was close; his mother, Maria Panteleyevna Gorbacheva (née Gopkalo), was colder and punitive.[8] His parents were poor,[9] and lived as peasants.[10] They had married as teenagers in 1928,[11] and in keeping with local tradition had initially resided in Sergei's father's house, an adobe-walled hut, before a hut of their own could be built.[12]

The Soviet Union was a one-party state governed by the Communist Party, and during Gorbachev's childhood was under the leadership of Joseph Stalin. Stalin had initiated a project of mass rural collectivization which, in keeping with his Marxist-Leninist ideas, he believed would help convert the country into a socialist society.[13] Gorbachev's maternal grandfather joined the Communist Party and helped form the village's first kolkhoz (collective farm) in 1929, becoming its chair.[14] This farm was 19 kilometres (12 mi) outside Privolnoye village and when he was three years old, Gorbachev left his parental home and moved into the kolkhoz with his maternal grandparents.[15]

The country was then experiencing the famine of 1932–33, in which two of Gorbachev's paternal uncles and an aunt died.[16] This was followed by the Great Purge, in which individuals accused of being "enemies of the people"—including those sympathetic to rival interpretations of Marxism like Trotskyism—were arrested and interned in labor camps, if not executed. Both of Gorbachev's grandfathers were arrested—his maternal in 1934 and his paternal in 1937—and both spent time in Gulag labor camps prior to being released.[17] After his December 1938 release, Gorbachev's maternal grandfather discussed having been tortured by the secret police, an account that influenced the young boy.[18]

Following on from the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, in June 1941 the German Army invaded the Soviet Union. German forces occupied Privolnoye for four and a half months in 1942.[19] Gorbachev's father had joined the Soviet Red Army and fought on the frontlines; he was wrongly declared dead during the conflict and fought in the Battle of Kursk before returning to his family, injured.[20] After Germany was defeated, Gorbachev's parents had their second son, Aleksandr, in 1947; he and Mikhail would be their only children.[11]

The village school had closed during much of the war but re-opened in autumn 1944.[21] Gorbachev did not want to return but when he did he excelled academically.[22] He read voraciously, moving from the Western novels of Thomas Mayne Reid to the work of Vissarion Belinsky, Alexander Pushkin, Nikolai Gogol, and Mikhail Lermontov.[23] In 1946, he joined Komsomol, the Soviet political youth organization, becoming leader of his local group and then being elected to the Komsomol committee for the district.[24] From primary school he moved to the high school in Molotovskeye; he stayed there during the week while walking the 19 km (12 mi) home during weekends.[25] As well as being a member of the school's drama society,[26] he organized sporting and social activities and led the school's morning exercise class.[27] Over the course of five consecutive summers from 1946 onward he returned home to assist his father operate a combine harvester, during which they sometimes worked 20-hour days.[28] In 1948, they harvested over 8000 centners of grain, a feat for which Sergey was awarded the Order of Lenin and his son the Order of the Red Banner of Labour.[29]

University: 1950–1955

— Gorbachev's letter requesting membership of the Communist Party, 1950[30]

In June 1950, Gorbachev became a candidate member of the Communist Party.[30] He also applied to study at the law school of Moscow State University (MSU), then the most prestigious university in the country. They accepted without asking for an exam, likely because of his worker-peasant origins and his possession of the Order of the Red Banner of Labour.[31] His choice of law was unusual; it was not a well-regarded subject in Soviet society at that time.[32] Aged 19, he traveled by train to Moscow, the first time he had left his home region.[33]

In the city, he resided with fellow MSU students at a dormitory in Sokolniki District.[34] He and other rural students felt at odds with their Muscovite counterparts but he soon came to fit in.[35] Fellow students recall him working especially hard, often late into the night.[36] He gained a reputation as a mediator during disputes,[37] and was also known for being outspoken in class, although would only reveal a number of his views privately; for instance he confided in some students his opposition to the Soviet jurisprudential norm that a confession proved guilt, noting that confessions could have been forced.[38] During his studies, an anti-semitic campaign spread through the Soviet Union, culminating in the Doctors' plot; Gorbachev publicly defended a Jewish student who was accused of disloyalty to the country by one of their fellows.[39]

At MSU, he became the Komsomol head of his entering class, and then Komsomol's deputy secretary for agitation and propaganda at the law school.[40] One of his first Komsomol assignments in Moscow was to monitor the election polling in Krasnopresnenskaya district to ensure the government's desire for near total turnout; Gorbachev found that most of those who voted did so "out of fear".[41] In 1952, he was appointed a full member of the Communist Party.[42] As a party and Komsomol member he was tasked with monitoring fellow students for potential subversion; some of his fellow students said that he did so only minimally and that they trusted him to keep confidential information secret from the authorities.[43] Gorbachev became close friends with Zdeněk Mlynář, a Czechoslovak student who later became a primary ideologist of the 1968 Prague Spring. Mlynář recalled that the duo remained committed Marxist-Leninists despite their growing concerns about the Stalinist system.[44] After Stalin died in March 1953, Gorbachev and Mlynář joined the crowds amassing to see Stalin's body laying in state.[45]

At MSU, Gorbachev met Raisa Titarenko, a Ukrainian studying in the university's philosophy department.[46] She was engaged to another man but after that engagement fell apart, she began a relationship with Gorbachev;[47] together they went to bookstores, museums, and art exhibits.[48] In early 1953, he took an internship at the procurator's office in Molotovskoye district, but was angered by the incompetence and arrogance of those working there.[49] That summer, he returned to Privolnoe to work with his father on the harvest; the money earned allowed him to pay for a wedding.[50] On 25 September 1953 he and Raisa registered their marriage at Sokolniki Registry Office;[50] and in October moved in together at the Lenin Hills dormitory.[51] Raisa discovered that she was pregnant and although the couple wanted to keep the child she fell ill and required a life-saving abortion.[52]

In June 1955, Gorbachev graduated with a distinction;[53] his final paper had been on the advantages of "socialist democracy" (the Soviet political system) over "bourgeois democracy" (liberal democracy).[54] He was subsequently assigned to the Soviet Procurator's office, which was then focusing on the rehabilitation of the innocent victims of Stalin's purges, but found that they had no work for him.[55] He was then offered a place on an MSU graduate course specializing in kolkhoz law, but declined.[56] He had wanted to remain in Moscow, where Raisa was enrolled on a PhD program, but instead gained employment in Stavropol; Raisa abandoned her studies to join him there.[57]

Rise in the Communist Party

Stavropol Komsomol: 1955–1969

In August 1955, Gorbachev started work at the Stavropol regional procurator's office, but disliked the job and used his contacts to get a transfer to work for Komsomol,[58] becoming deputy director of Komsomol's agitation and propaganda department for that region.[59] In this position, he visited villages in the area and tried to improve the lives of their inhabitants; he established a discussion circle in Gorkaya Balka village to help its peasant residents gain social contacts.[60]

Gorbachev and his wife initially rented a small room in Stavropol,[61] taking daily evening walks around the city and on weekends hiking in the countryside.[62] In January 1957, Raisa gave birth to a daughter, Irina,[63] and in 1958 they moved into two rooms in a communal apartment.[64] In 1961, Gorbachev pursued a second degree, on agricultural production; he took a correspondence course from the local Stavropol Agricultural Institute, receiving his diploma in 1967.[65] His wife had also pursued a second degree, attaining a PhD in sociology in 1967 from the Moscow Pedagogical Institute;[66] while in Stavropol she too joined the Communist Party.[67]

Stalin was ultimately succeeded as Soviet leader by Nikita Khrushchev, who denounced Stalin and his cult of personality in a speech given in February 1956, after which he launched a de-Stalinization process throughout Soviet society.[68] Later biographer William Taubman suggested that Gorbachev "embodied" the "reformist spirit" of the Khrushchev era.[69] Gorbachev was among those who saw themselves as "genuine Marxists" or "genuine Leninists" in contrast to what they regarded as the perversions of Stalin.[70] He helped spread Khrushchev's anti-Stalinist message in Stavropol, but encountered many who continued to regard Stalin as a hero or who praised the Stalinist purges as just.[71]

Gorbachev rose steadily through the ranks of the local administration.[72] The authorities regarded him as politically reliable,[73] and he would flatter his superiors, for instance gaining favor with prominent local politician Fyodor Kulakov.[74] With an ability to outmanoeuvre rivals, some colleagues resented his success.[75] In September 1956, he was promoted First Secretary of the Stavropol city's Komsomol, placing him in charge of it;[76] in April 1958 he was made deputy head of the Komsomol for the entire region.[77] At this point he was given better accommodation: a two-room flat with its own private kitchen, toilet, and bathroom.[78] In Stavropol, he formed a discussion club for youths,[79] and helped mobilize local young people to take part in Khrushchev's agricultural and development campaigns.[80]

In March 1961, Gorbachev became First Secretary of the regional Komsomol,[81] in which position he went out of his way to appoint women as city and district leaders.[82] In 1961, Gorbachev played host to the Italian delegation for the World Youth Festival in Moscow;[83] that October, he also attended the 22nd Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.[84] In January 1963, Gorbachev was promoted to personnel chief for the regional party's agricultural committee,[85] and in September 1966 became First Secretary of the Stavropol City Party Organization ("Gorkom").[86] By 1968 he was increasingly frustrated with his job—in large part because Khrushchev's reforms were stalling or being reversed—and he contemplated leaving politics to work in academia.[87] However, in August 1968, he was named Second Secretary of the Stavropol Kraikom, making him the deputy of First Secretary Leonid Yefremov and the second most senior figure in the Stavrapol region.[88] In 1969 he was elected as a deputy to the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union and made a member of its Standing Commission for the Protection of the Environment.[89]

Cleared for travel to Eastern Bloc countries, in 1966 he was part of a delegation visiting East Germany, and in 1969 and 1974 visited Bulgaria.[90] In August 1968 the Soviet Union led an invasion of Czechoslovakia to put an end to the Prague Spring, a period of political liberalization in the Marxist–Leninist country. Although Gorbachev later stated that he had had private concerns about the invasion, he publicly supported it.[91] In September 1969 he was part of a Soviet delegation sent to Czechoslovakia, where he found the Czechoslovak people largely unwelcoming to them.[92] That year, the Soviet authorities ordered him to punish Fagien B. Sadykov, a Stavropol-based agronomist whose ideas were regarded as critical of Soviet agricultural policy; Gorbachev ensured that Sadykov was fired from teaching but ignored calls for him to face tougher punishment.[93] Gorbachev later related that he was "deeply affected" by the incident; "my conscience tormented me" for overseeing Sadykov's persecution.[94]

Heading the Stavropol Region: 1970–1977

In April 1970, Yefremov was promoted to a higher position in Moscow and Gorbachev succeeded him as the First Secretary of the Stavropol kraikom. This granted Gorbachev significant power over the Stavropol region.[95] He had been personally vetted for the position by senior Kremlin leaders and was informed of their decision by the Soviet leader, Leonid Brezhnev.[96] Aged 39, he was considerably younger than his predecessors in the position.[97] As head of the Stavropol region, he automatically became a member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1971.[98] According to biographer Zhores Medvedev, Gorbachev "had now joined the Party's super-elite".[99] As regional leader, Gorbachev initially attributed economic and other failures to "the inefficiency and incompetence of cadres, flaws in management structure or gaps in legislation", but eventually concluded that they were caused by an excessive centralization of decision making in Moscow.[100] He began reading translations of restricted texts by Western Marxist authors like Antonio Gramsci, Louis Aragon, Roger Garaudy, and Giuseppe Boffa, and came under their influence.[100]

Gorbachev's main task as regional leader was to raise agricultural production levels, something hampered by severe droughts in 1975 and 1976.[101] He oversaw the expansion of irrigation systems through construction of the Great Stavropol Canal.[102] For overseeing a record grain harvest in Ipatovsky district, in March 1972 he was awarded by Order of the October Revolution by Brezhnev in a Moscow ceremony.[103] Gorbachev always sought to maintain Brezhnev's trust;[104] as regional leader, he repeatedly praised Brezhnev in his speeches, for instance referring to him as "the outstanding statesman of our time".[105] Gorbachev and his wife holidayed in Moscow, Leningrad, Uzbekistan, and resorts in the North Caucusus;[106] he holidayed with the head of the KGB, Yuri Andropov, who was favorable towards him and who became an important patron.[107] Gorbachev also developed good relationships with senior figures like the Soviet Prime Minister, Alexei Kosygin,[108] and the longstanding senior party member Mikhail Suslov.[109]

The government considered Gorbachev sufficiently reliable that he was sent as part of Soviet delegations to Western Europe; he made five trips there between 1970 and 1977.[110] In September 1971 he was part of a delegation who traveled to Italy, where they met with representatives of the Italian Communist Party; Gorbachev loved Italian culture but was struck by the poverty and inequality he saw in the country.[111] In 1972 he visited Belgium and the Netherlands and in 1973 West Germany.[112] Gorbachev and his wife visited France in 1976 and 1977, on the latter occasion touring the country with a guide from the French Communist Party.[113] He was surprised by how openly West Europeans offered their opinions and criticized their political leaders, something absent from the Soviet Union, where most people did not feel safe speaking so openly.[114] He later related that for him and his wife, these visits "shook our a priori belief in the superiority of socialist over bourgeois democracy".[115]

Gorbachev had remained close to his parents; after his father became terminally ill in 1974, Gorbachev traveled to be with him in Privolnoe shortly before his death.[116] His daughter, Irina, married fellow student Anatoly Virgansky in April 1978.[117] In 1977, the Supreme Soviet appointed Gorbachev to chair the Standing Commission on Youth Affairs due to his experience with mobilizing young people in Komsomol.[118]

Secretary of the Central Committee: 1978–1984

In November 1978, Gorbachev was appointed a Secretary of the Central Committee.[119] His appointment had been approved unanimously by the Central Committee's members.[120] To fill this position, Gorbachev and his wife moved to Moscow, where they were initially given an old dacha outside the city. They then moved to another, at Sosnovka, before finally being allocated a newly built brick house.[121] He was also given an apartment inside the city, but gave that to his daughter and son-in-law; Irina had begun work at Moscow's Second Medical Institute.[122] As part of the Moscow political elite, Gorbachev and his wife now had access to better medical care and to specialized shops; they were also given cooks, servants, bodyguards, and secretaries, although many of these were spies for the KGB.[123] In his new position, Gorbachev often worked twelve to sixteen hour days.[123] He and his wife socialized little, but liked to visit Moscow's theaters and museums.[124]

In 1978, Gorbachev was appointed to the Central Committee's Secretariat for Agriculture, replacing his old friend Kulakov, who had died of a heart attack.[125] Gorbachev concentrated his attentions on agriculture: the harvests of 1979, 1980, and 1981 were all poor, due largely to weather conditions,[126] and the country had to import increasing quantities of grain.[127] He had growing concerns about the country's agricultural management system, coming to regard it as overly centralized and requiring more bottom-up decision making;[128] he raised these points at his first speech at a Central Committee Plenum, given in July 1978.[129] He began to have concerns about other policies too. In December 1979, the Soviets sent the Red Army into neighbouring Afghanistan to support its Soviet-aligned government against Islamist insurgents; Gorbachev privately thought it a mistake.[130] At times he openly supported the government position; in October 1980 he for instance endorsed Soviet calls for Poland's Marxist–Leninist government to crack down on growing internal dissent in that country.[130] That same month, he was promoted from a candidate member to a full member of the Politburo, the highest decision-making authority in the Communist Party.[131] At the time, he was the Politburo's youngest member.[131]

After Brezhnev's death in November 1982, Andropov succeeded him as General Secretary of the Communist Party, the de facto head of government in the Soviet Union. Gorbachev was enthusiastic about the appointment.[132] However, although Gorbachev hoped that Andropov would introduce liberalizing reforms, the latter carried out only personnel shifts rather than structural change.[133] Gorbachev became Andropov's closest ally in the Politburo;[134] with Andropov's encouragement, Gorbachev sometimes chaired Politburo meetings.[135] Andropov encouraged Gorbachev to expand into policy areas other than agriculture, preparing him for future higher office.[136] In April 1983, Gorbachev delivered the annual speech marking the birthday of the Soviet founder Vladimir Lenin;[137] this required him re-reading many of Lenin's later writings, in which the latter had called for reform in the context of the New Economic Policy of the 1920s, and encouraged Gorbachev's own conviction that reform was needed.[138] In May 1983, Gorbachev was sent to Canada, where he met Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and spoke to the Canadian Parliament.[139] There, he met and befriended the Soviet ambassador, Aleksandr Yakovlev, who later became a key political ally.[140]

In February 1984, Andropov died; on his deathbed he indicated his desire that Gorbachev succeed him.[141] Many in the Central Committee nevertheless thought the 53-year old Gorbachev was too young and inexperienced.[142] Instead, Konstantin Chernenko—a longstanding Brezhnev ally—was appointed General Secretary, but he too was in very poor health.[143] Chernenko was often too sick to chair Politburo meetings, with Gorbachev stepping in last minute.[144] Gorbachev continued to cultivate allies both in the Kremlin and beyond,[145] and also gave the main speech at a conference on Soviet ideology, where he angered party hardliners by implying that the country required reform.[146]

In April 1984, he was appointed chair of the Foreign Affairs Committee of the Soviet legislature, a largely honorific position.[147] In June he traveled to Italy as a Soviet representative for the funeral of Italian Communist Party leader Enrico Berlinguer,[148] and in September to Sofia, Bulgaria to attend celebrations of the fortieth anniversary of its liberation by the Red Army.[149] In December, he visited Britain at the request of its Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher; she was aware that he was a potential reformer and wanted to meet him.[150] At the end of the visit, Thatcher said: "I like Mr Gorbachev. We can do business together".[151] He felt that the visit helped to erode Andrei Gromyko's dominance of Soviet foreign policy while at the same time sending a signal to the United States government that he wanted to improve Soviet-U.S. relations.[152]

General Secretary of the CPSU

On 10 March 1985, Chernenko died.[153] Gromyko proposed Gorbachev as the next General Secretary; as a longstanding party member, Gromyko's recommendation carried great weight among the Central Committee.[154] Gorbachev expected much opposition to his nomination as General Secretary, but ultimately the rest of the Politburo supported him.[155] Shortly after Chernenko's death, the Politburo unanimously elected Gorbachev as his successor; they wanted him over another elderly leader.[156] He thus became the eighth leader of the Soviet Union.[10] Few in the government imagined that he would be as radical a reformer as he proved.[157] Although not a well-known figure to the Soviet public, there was widespread relief that the new leader was not elderly and ailing.[158] Gorbachev's first public appearance as leader was at Chernenko's Red Square funeral, held on 14 March.[159] Two months after being elected, he left Moscow for the first time, traveling to Leningrad, where he spoke to assembled crowds.[160] In June he traveled to Ukraine, in July to Belarus, and in September to Tyumen Oblast, urging party members in these areas to take more responsibility for fixing local problems.[161]

Early years: 1985–1986

Gorbachev's leadership style differed from that of his predecessors. He would stop to talk to civilians on the street, forbade the display of his portrait at the 1985 Red Square holiday celebrations, and encouraged frank and open discussions at Politburo meetings.[162] To the West, Gorbachev was seen as a more moderate and less threatening Soviet leader; some Western commentators however believed this an act to lull Western governments into a false sense of security.[163] His wife was his closest adviser, and took on the unofficial role of a "first lady" by appearing with him on foreign trips; her public visibility was a breach of standard practice and generated resentment.[164] His other close aides were Georgy Shakhnazarov and Anatoly Chernyaev.[165]

Gorbachev was aware that the Politburo could remove him from office, and that he could not pursue more radical reform without a majority of supporters in the Politburo.[166] He sought to remove several older members from the Politburo, encouraging Grigory Romanov, Nikolai Tikhonov, and Viktor Grishin into retirement.[167] He promoted Gromyko to head of state, a largely ceremonial role with little influence, and moved his own ally, Eduard Shevardnadze, to Gromyko's former post in charge of foreign policy.[168] Other allies whom he saw promoted were Yakovlev, Anatoly Lukyanov, and Vadim Medvedev.[169] Another of those promoted by Gorbachev was Boris Yeltsin, who was made a Secretary of the Central Committee in July 1985.[170] Most of these appointees were from a new generation of well-educated officials who had been frustrated during the Brezhnev era.[171] In his first year, 14 of the 23 heads of department in the secretariat were replaced.[172] Doing so, Gorbachev secured dominance in the Politburo within a year, faster than either Stalin, Khrushchev, or Brezhnev had achieved.[173]

Domestic policies

Gorbachev recurrently employed the term perestroika, first used publicly in March 1984.[174] He saw perestroika as encompassing a complex series of reforms to restructure society and the economy.[175] He was concerned by the country's low productivity, poor work ethic, and inferior quality goods;[176] like several economists, he feared this would lead to the country becoming a second-rate power.[177] The first stage of Gorbachev's perestroika was uskoreniye ("acceleration"), a term he used regularly in the first two years of his leadership.[178] The Soviet Union was behind the United States in many areas of production,[179] but Gorbachev claimed that it would accelerate industrial output to match that of the U.S. by 2000.[180] The Five Year Plan of 1985–90 was targeted to expand machine building by 50 to 100%.[181] To boost agricultural productivity, he merged five ministries and a state committee into a single entity, Agroprom, although by late 1986 acknowledged this merger as a failure.[182]

The purpose of reform was to prop up the centrally planned economy—not to transition to market socialism. Speaking in late summer 1985 to the secretaries for economic affairs of the central committees of the East European communist parties, Gorbachev said: "Many of you see the solution to your problems in resorting to market mechanisms in place of direct planning. Some of you look at the market as a lifesaver for your economies. But, comrades, you should not think about lifesavers but about the ship, and the ship is socialism."[183] Gorbachev's perestroika also entailed attempts to move away from technocratic management of the economy by increasingly involving the labor force in industrial production.[184] He was of the view that once freed from the strong control of central planners, state-owned enterprises would act as market agents.[185] Gorbachev and other Soviet leaders did not anticipate opposition to the perestroika reforms; according to their interpretation of Marxism, they believed that in a socialist society like the Soviet Union there would not be "antagonistic contradictions".[186] However, there would come to be a public perception in the country that many bureaucrats were paying lip service to the reforms while trying to undermine them.[187] He also initiated the concept of gospriyomka (state acceptance of production) during his time as leader,[188] which represented quality control.[189] In April 1986, he introduced an agrarian reform which linked salaries to output and allowed collective farms to sell 30% of their produce directly to shops or co-operatives rather than giving it all to the state for distribution.[190] In a September 1986 speech, he embraced the idea of reintroducing market economics to the country alongside limited private enterprise, citing Lenin's New Economic Policy as a precedent; he nevertheless stressed that he did not regard this as a return to capitalism.[190]

In the Soviet Union, alcohol consumption had risen steadily between 1950 and 1985.[191] By the 1980s, drunkenness was a major social problem and Andropov had planned a major campaign to limit alcohol consumption. Encouraged by his wife, Gorbachev—who believed the campaign would improve health and work efficiency—oversaw its implementation.[192] Alcohol production was reduced by around 40 percent, the legal drinking age rose from 18 to 21, alcohol prices were increased, stores were banned from selling it before 2pm, and tougher penalties were introduced for workplace or public drunkenness and home production of alcohol.[193] The All-Union Voluntary Society for the Struggle for Temperance was formed to promote sobriety; it had over 14 million members within three years.[194] As a result, crime rates fell and life expectancy grew slightly between 1986 and 1987.[195] However, moonshine production rose considerably,[196] and the reform had significant costs to the Soviet economy, resulting in losses of up to US$100 billion between 1985 and 1990.[197] Gorbachev later considered the campaign to have been an error,[198] and it was terminated in October 1988.[199] After it ended, it took several years for production to return to previous levels, after which alcohol consumption soared in Russia between 1990 and 1993.[200]

In the second year of his leadership, Gorbachev began speaking of glasnost, or "openness".[201] According to Doder and Branston, this meant "greater openness and candour in government affairs and for an interplay of different and sometimes conflicting views in political debates, in the press, and in Soviet culture."[202] Encouraging reformers into prominent media positions, he brought in Sergei Zalygin as head of Novy Mir magazine and Yegor Yakovlev as editor-in-chief of Moscow News.[203] He made the historian Yuri Afanasiev dean of the State Historical Archive Faculty, from where Afansiev could press for the opening of secret archives and the reassessment of Soviet history.[171] Prominent dissidents like Andrei Sakharov were freed from internal exile or prison.[204] Gorbachev saw glasnost as a necessary measure to ensure perestroika by alerting the Soviet populace to the nature of the country's problems in the hope that they would support his efforts to fix them.[205] Particularly popular among the Soviet intelligentsia, who became key Gorbachev supporters,[206] glasnost boosted his domestic popularity but alarmed many Communist Party hardliners.[207] For many Soviet citizens, this newfound level of freedom of speech and press—and its accompanying revelations about the country's past—was uncomfortable.[208]

Some in the party thought Gorbachev was not going far enough in his reforms; a prominent liberal critic was Yeltsin. He had risen rapidly since 1985, attaining the role of Moscow city boss.[209] Like many members of the government, Gorbachev was skeptical of Yeltsin, believing that he engaged in too much self-promotion.[210] Yeltsin was also critical of Gorbachev, regarding him as patronizing.[209] In early 1986, Yeltsin began sniping at Gorbachev in Politburo meetings.[210] At the Twenty-Seventh Party Congress in February, Yeltsin called for more far-reaching reforms than Gorbachev was initiating and criticized the party leadership, although did not cite Gorbachev by name, claiming that a new cult of personality was forming. Gorbachev then opened the floor to responses, after which attendees publicly criticized Yeltsin for several hours.[211] After this, Gorbachev also criticized Yeltsin, claiming that he only cared for himself and was "politically illiterate".[212] Yeltsin then resigned as both Moscow boss and as a member of the Politburo.[212] From this point, tensions between the two men developed into a mutual hatred.[213]

In April 1986 the Chernobyl disaster occurred.[214] In the immediate aftermath, officials fed Gorbachev incorrect information to downplay the incident. As the scale of the disaster became apparent, 336,000 people were evacuated from the area around Chernobyl.[215] Taubman noted that the disaster marked "a turning point for Gorbachev and the Soviet regime".[216] Several days after it occurred, he gave a televised report to the nation.[217] He cited the disaster as evidence for what he regarded as widespread problems in Soviet society, such as shoddy workmanship and workplace inertia.[218] Gorbachev later described the incident as one which made him appreciate the scale of incompetence and cover-ups in the Soviet Union.[216] From April to the end of the year, Gorbachev became increasingly open in his criticism of the Soviet system, including food production, state bureaucracy, the military draft, and the large size of the prison population.[219]

Foreign policy

In a May 1985 speech given to the Soviet Foreign Ministry—the first time a Soviet leader had directly addressed his country's diplomats—Gorbachev spoke of a "radical restructuring" of foreign policy.[220] A major issue facing his leadership was Soviet involvement in the Afghan Civil War, which had then been going on for over five years.[221] Over the course of the war, the Soviet Army took heavy casualties and there was much opposition to Soviet involvement among both the public and military.[221] On becoming leader, Gorbachev saw withdrawal from the war as a key priority.[222] In October 1985, he met with Afghan Marxist leader Babrak Karmal, urging him to acknowledge the lack of widespread public support for his government and pursue a power sharing agreement with the opposition.[222] That month, the Politburo approved Gorbachev's decision to withdraw combat troops from Afghanistan, although the last troops did not leave until February 1989.[223]

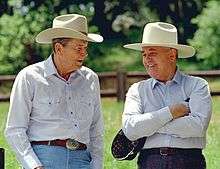

Gorbachev had inherited a renewed period of high tension in the Cold War.[224] He believed strongly in the need to sharply improve relations with the United States; he was appalled at the prospect of nuclear war, was aware that the Soviet Union was unlikely to win the arms race, and thought that the continued focus on high military spending was detrimental to his desire for domestic reform.[224] Although privately also appalled at the prospect of nuclear war, U.S. President Ronald Reagan publicly appeared to not want a de-escalation of tensions, having scrapped détente and arms controls, initiating a military build-up, and calling the Soviet Union the "evil empire".[225]

Both Gorbachev and Reagan wanted a summit to discuss the Cold War, but each faced some opposition to such a move within their respective governments.[226] They agreed to hold a summit in Geneva, Switzerland in November 1985.[227] In the buildup to this, Gorbachev sought to improve relations with the U.S.' NATO allies, visiting France in October 1985 to meet with President François Mitterrand.[228] At the Geneva summit, discussions between Gorbachev and Reagan were sometimes heated, and Gorbachev was initially frustrated that his U.S. counterpart "does not seem to hear what I am trying to say".[229] As well as discussing the Cold War proxy conflicts in Afghanistan and Nicaragua and human rights issues, the pair discussed the U.S.' Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), to which Gorbachev was strongly opposed.[230] The duo's wives also met and spent time together at the summit.[231] The summit ended with a joint commitment to avoiding nuclear war and to meet for two further summits: in Washington D.C. in 1986 and in Moscow in 1987.[230] Following the conference, Gorbachev traveled to Prague to inform other Warsaw Pact leaders of developments.[232]

In January 1986, Gorbachev publicly proposed a three-stage programme for abolishing the world's nuclear weapons by the end of the 20th century.[234] An agreement was then reached to meet with Reagan in Reykjavík, Iceland in October 1986. Gorbachev wanted to secure guarantees that SDI would not be implemented, and in return was willing to offer concessions, including a 50% reduction in Soviet long range nuclear missiles.[235] Both leaders agreed with the shared goal of abolishing nuclear weapons, but Reagan refused to terminate the SDI program and no deal was reached.[236] After the summit, many of Reagan's allies criticized him for going along with the idea of abolishing nuclear weapons.[237] Gorbachev meanwhile told the Politburo that Reagan was "extraordinarily primitive, troglodyte, and intellectually feeble".[237]

In his relations with the developing world, Gorbachev found many of the leaders professing revolutionary socialist credentials or a pro-Soviet attitude—such as Libya's Muammar Gaddafi and Syria's Hafez al-Assad—frustrating, and his best personal relationship was instead with India's Prime Minister, Rajiv Gandhi.[221] He thought that the "socialist camp" of Marxist-Leninist governed states—the Eastern Bloc countries, North Korea, Vietnam, and Cuba—were a drain on the Soviet economy, receiving a far greater amount of goods from the Soviet Union than they collectively gave in return.[238] He sought improved relations with China, a country whose Marxist government had severed ties with the Soviets in the Sino-Soviet Split and had since undergone its own structural reform. In June 1985 he signed a US$14 billion five-year trade agreement with the country and in July 1986, he proposed troop reductions along the Soviet-Chinese border, hailing China as "a great socialist country".[239] He made clear his desire for Soviet membership of the Asian Development Bank and for greater ties to Pacific countries, especially China and Japan.[240]

Further reform: 1987–1989

Domestic reforms

In January 1987, Gorbachev attended a Central Committee plenum where he talked about perestroika and democratization while criticizing widespread corruption.[241] He considered putting a proposal to allow multi-party elections into his speech, but decided against doing so.[242] After the plenum, he focused his attentions on economic reform, holding discussions with government officials and economists.[243] Many economists proposed reducing ministerial controls on the economy and allowing state-owned enterprises to set their own targets; Ryzhkov and other government figures were skeptical.[244] In June, Gorbachev finished his report on economic reform. It reflected a compromise: ministers would retain the ability to set output targets but these would not be considered binding.[245] That month, a plenum accepted his recommendations and the Supreme Soviet passed a "law on enterprises" implementing the changes.[246] Economic problems remained: by the late 1980s there were still widespread shortages of basic goods, rising inflation, and declining living standards.[247] These stoked a number of miners' strikes in 1989.[248]

By 1987, the ethos of glasnost had spread through Soviet society: journalists were writing increasingly openly,[249] many economic problems were being publicly revealed,[250] and studies appeared that critically reassessed Soviet history.[251] Gorbachev was broadly supportive, describing glasnost as "the crucial, irreplaceable weapon of perestroika".[249] He nevertheless insisted that people should use the newfound freedom responsibly, stating that journalists and writers should avoid "sensationalism" and be "completely objective" in their reporting.[252] Nearly two hundred previously restricted Soviet films were publicly released, and a range of Western films were also made available.[253] In 1989, Soviet responsibility for the 1940 Katyn massacre was finally revealed.[254]

In September 1987, the government stopped jamming the signal of the British Broadcasting Corporation and Voice of America.[255] The reforms also included greater tolerance of religion;[256] an Easter service was broadcast on Soviet television for the first time and the millennium celebrations of the Russian Orthodox Church were given media attention.[257] Independent organizations appeared, most supportive of Gorbachev, although the largest, Pamyat, was ultra-nationalist and anti-Semitic in nature.[258] Gorbachev also announced that Soviet Jews wishing to migrate to Israel would be allowed to do so, something previously prohibited.[259]

In August 1987, Gorbachev holidayed in Nizhniaia Oreanda, Ukraine, there writing Perestroika: New Thinking for Our Country and Our World at the suggestion of U.S. publishers.[260] For the 70th anniversary of the October Revolution of 1917—which brought Lenin and the Communist Party to power—Gorbachev produced a speech on "October and Perestroika: The Revolution Continues". Delivered to a ceremonial joint session of the Central Committee and the Supreme Soviet in the Kremlin Palace of Congresses, it praised Lenin but criticized Stalin for overseeing mass human rights abuses.[261] Party hardliners thought the speech went too far; liberalisers thought it did not go far enough.[262]

In March 1988, the magazine Sovetskaya Rossiya published an open letter by the teacher Nina Andreyeva. It criticized elements of Gorbachev's reforms, attacking what she regarded as the denigration of the Stalinist era and arguing that a reformer clique—whom she implied were mostly Jews and ethnic minorities—were to blame.[263] Over 900 Soviet newspapers reprinted it and anti-reformists rallied around it; many reformers panicked, fearing a backlash against perestroika.[264] On returning from Yugoslavia, Gorbachev called a Politburo meeting to discuss the letter, at which he confronted those hardliners supporting its sentiment. Ultimately, the Politburo arrived at a unanimous decision to express disapproval of Andreyeva's letter and publish a rebuttal in Pravda.[265] Yakovlev and Gorbachev's rebuttal claimed that those who "look everywhere for internal enemies" were "not patriots" and presented Stalin's "guilt for massive repressions and lawlessness" as "enormous and unforgiveable".[266]

Forming the Congress of People's Deputies

Although the next party congress was not scheduled until 1991, Gorbachev convened the 19th Party Conference in its place in June 1988. He hoped that by allowing a broader range of people to attend than at previous conferences, he would gain additional support for his reforms.[267] With sympathetic officials and academics, Gorbachev drafted plans for reforms that would shift power away from the Politburo and towards the soviets. While the soviets had become largely powerless bodies that rubber-stamped Politburo policies, he wanted them to become year-round legislatures. He proposed the formation of a new institution, the Congress of People's Deputies, whose members were to be elected in a largely free vote.[268] This congress would in turn elect a USSR Supreme Soviet, which would do most of the legislating.[269]

These proposals reflected Gorbachev's desire for more democracy; however, in his view there was a major impediment in that the Soviet people had developed a "slave psychology" after centuries of Tsarist autocracy and Marxist-Leninist authoritarianism.[270] Held at the Kremlin Palace of Congresses, the conference brought together 5,000 delegates and featured arguments between hardliners and liberalisers. The proceedings were televised, and for the first time since the 1920s, voting was not unanimous.[271] In the months following the conference, Gorbachev focused on redesigning and streamlining the party apparatus; the Central Committee staff—which then numbered around 3,000—was halved, while various Central Committee departments were merged to cut down the overall number from twenty to nine.[272]

In March and April 1989, elections to the new Congress were held.[273] Of the 2,250 legislators to be elected, one hundred — termed the "Red Hundred" by the press — were directly chosen by the Communist Party, with Gorbachev ensuring many were reformists.[274] Although over 85% of elected deputies were party members,[275] many of those elected—including Sakharov and Yeltsin—were liberalisers.[276] Gorbachev was happy with the result, describing it as "an enormous political victory under extraordinarily difficult circumstances".[277] The new Congress convened in May 1989.[278] Gorbachev was then elected its chair – the new de facto head of state – with 2,123 votes in favor to 87 against.[279] Its sessions were televised live,[279] and its members elected the new Supreme Soviet.[280] At the Congress, Sakharov spoke repeatedly, exasperating Gorbachev with his calls for greater liberalization and the introduction of private property.[281] When Sakharov died shortly after, Yeltsin became the figurehead of the liberal opposition.[282]

Relations with China and Western states

Gorbachev tried to improve relations with the UK, France, and West Germany;[283] like previous Soviet leaders, he was interested in pulling Western Europe away from U.S. influence.[284] Calling for greater pan-European co-operation, he publicly spoke of a "Common European Home" and of a Europe "from the Atlantic to the Urals".[285] In March 1987, Thatcher visited Gorbachev in Moscow; despite their ideological differences, they liked one another.[286] In April 1989 he visited London, lunching with Elizabeth II.[287] In May 1987, Gorbachev again visited France, and in November 1988 Mitterrand visited him in Moscow.[288] The West German Chancellor, Helmut Kohl, had initially offended Gorbachev by comparing him to Nazi propagandist Joseph Goebbels, although later informally apologized and in October 1988 visited Moscow.[289] In June 1989 Gorbachev then visited Kohl in West Germany.[290] In November 1989 he also visited Italy, meeting with Pope John Paul II.[291] Gorbachev's relationships with these West European leaders were typically far warmer than those he had with their Eastern Bloc counterparts.[292]

Gorbachev continued to pursue good relations with China to heal the Sino-Soviet Split. In May 1989 he visited Beijing and there met its leader Deng Xiaoping; Deng shared Gorbachev's belief in economic reform but rejected calls for democratization.[293] Pro-democracy students had amassed in Tiananmen Square during Gorbachev's visit but after he left were massacred by troops. Gorbachev did not condemn the massacre publicly but it reinforced his commitment not to use violent force in dealing with pro-democracy protests in the Eastern Bloc.[294]

Following the failures of earlier talks with the U.S., in February 1987, Gorbachev held a conference in Moscow, titled "For a World without Nuclear Weapons, for Mankind's Survival", which was attended by various international celebrities and politicians.[295] By publicly pushing for nuclear disarmament, Gorbachev sought to give the Soviet Union the moral high ground and weaken the West's self-perception of moral superiority.[296] Aware that Reagan would not budge on SDI, Gorbachev focused on reducing "Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces", to which Reagan was receptive.[297] In April 1987, Gorbachev discussed the issue with U.S. Secretary of State George P. Shultz in Moscow; he agreed to eliminate the Soviets' SS-23 rockets and allow U.S. inspectors to visit Soviet military facilities to ensure compliance.[298] There was hostility to such compromises from the Soviet military, but following the May 1987 Mathias Rust incident—in which a West German teenager was able to fly undetected from Finland and land in Red Square—Gorbachev fired many senior military figures for incompetence.[299] In December 1987, Gorbachev visited Washington D.C., where he and Reagan signed the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty.[300] Taubman called it "one of the highest points of Gorbachev's career".[301]

A second U.S.-Soviet summit occurred in Moscow in May–June 1988, which Gorbachev expected to be largely symbolic.[302] Again, he and Reagan criticized each other's countries—Reagan raising Soviet restrictions on religious freedom; Gorbachev highlighting poverty and racial discrimination in the U.S.—but Gorbachev related that they spoke "on friendly terms".[303] They reached an agreement on notifying each other before conducting the ballistic missile test and made agreements on transport, fishing, and radio navigation.[304] At the summit, Reagan told reporters that he no longer considered the Soviet Union an "evil empire" and the duo revealed that they considered themselves friends.[305]

The third summit was held in New York City in December.[306] Arriving there, Gorbachev gave a speech to the United Nations Assembly where he announced a unilateral reduction in the Soviet armed forces by 500,000; he also announced that 50,000 troops would be withdrawn from Central and Eastern Europe.[307] He then met with Reagan and President-elect George H. W. Bush; he rushed home, skipping a planned visit to Cuba, to deal with the Armenian earthquake.[308] On becoming U.S. president, Bush appeared interested in continuing talks with Gorbachev but wanted to appear tougher on the Soviets than Reagan had to allay criticism from the right-wing of his Republican Party.[309] In December 1989, Gorbachev and Bush met at the Malta Summit.[310] Bush offered to assist the Soviet economy by suspending the Jackson-Vanik Amendment and repealing the Stevenson and Baird Amendments.[311] There, the duo agreed to a joint press conference, the first time that a U.S. and Soviet leader had done so.[312] Gorbachev also urged Bush to normalize relations with Cuba and meet its president, Fidel Castro, although Bush refused to do so.[313]

The nationality question and the Eastern Bloc

On taking power, Gorbachev found some unrest among different national groups within the Soviet Union. In December 1986, riots broke out in several Kazakh cities after a Russian was appointed head of the region.[314] In 1987, Crimean Tatars protested in Moscow to demand resettlement in Crimea, the area from which they had been deported on Stalin's orders in 1944. Gorbachev ordered a commission, headed by Gromyko, to examine their situation. Gromyko's report opposed calls for assisting Tatar resettlement in Crimea.[315] By 1988, the Soviet "nationality question" was increasingly pressing.[316] In February, the administration of the Nagorno-Karabakh region officially requested that it be transferred from the Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic to the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic; the majority of the region's population were ethnically Armenian and wanted unification with other majority Armenian areas.[317] As rival Armenian and Azerbaijani demonstrations took place in Nagorno-Karabakh, Gorbachev called an emergency meeting of the Politburo.[318] Ultimately, Gorbachev promised greater autonomy for Nagorno-Karabakh but refused the transfer, fearing that it would set off similar ethnic tensions and demands throughout the Soviet Union.[319]

That month, in the Azerbaijani city of Sumgait, Azerbaijani gangs began killing members of the Armenian minority. Local troops tried to quell the unrest but were attacked by mobs.[320] The Politburo ordered additional troops into the city, but in contrast to those like Ligachev who wanted a massive display of force, Gorbachev urged restraint. He believed that the situation could be resolved through a political solution, urging talks between the Armenian and Azerbaijani Communist Parties.[321] Further anti-Armenian violence broke out in Baku in 1990.[322] Problems also emerged in the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic; in April 1989, Georgian nationalists demanding independence clashed with troops in Tbilisi, resulting in various deaths.[323] Independence sentiment was also rising in the Baltic states; the Supreme Soviets of the Estonian, Lithuanian, and Latvian Soviet Socialist Republics declared their economic "autonomy" from Russia and introduced measures to restrict Russian immigration.[324] In August 1989, protesters formed the Baltic Way, a human chain across the three republics to symbolize their wish for independence.[325] That month, the Lithuanian Supreme Soviet ruled the 1940 Soviet annexation of their country to be illegal;[326] in January 1990, Gorbachev visited the republic to encourage it to remain part of the Soviet Union.[327]

Gorbachev rejected the "Brezhnev Doctrine", the idea that the Soviet Union had the right to intervene militarily in other Marxist-Leninist countries if their governments were threatened.[328] In December 1987 he announced the withdrawal of 500,000 Soviet troops from Central and Eastern Europe.[329] While pursuing domestic reforms, he did not publicly support reformers elsewhere in the Eastern Bloc.[330] Hoping instead to lead by example, he later related that he did not want to interfere in their internal affairs, but he may have feared that pushing reform in Central and Eastern Europe would have angered his own hardliners too much.[331] Some Eastern Bloc leaders, like Hungary's János Kádár and Poland's Wojciech Jaruzelski, were sympathetic to reform; others, like Romania's Nicolae Ceaușescu, were hostile to it.[332] In May 1987 Gorbachev visited Romania, where he was appalled by the state of the country, later telling the Politburo that there "human dignity has absolutely no value".[333] He and Ceaușescu disliked each other, and argued over Gorbachev's reforms.[334]

Unraveling of the USSR

In the Revolutions of 1989, most of the Marxist-Leninist states of Central and Eastern Europe held multi-party elections resulting in regime change.[335] In most countries, like Poland and Hungary, this was achieved peacefully, but in Romania the revolution turned violent and led to Ceaușescu's overthrow and execution.[335] Gorbachev was too preoccupied with domestic problems to pay much attention to these events.[336] He believed that democratic elections would not lead Eastern European countries into abandoning their commitment to socialism.[337] In 1989 he visited East Germany for the fortieth anniversary of its founding;[338] shortly after, in November, the East German government allowed its citizens to cross the Berlin Wall, a decision Gorbachev praised. Over following years, much of the wall was demolished.[339] Neither Gorbachev nor Thatcher or Mitterrand wanted a swift reunification of Germany, aware that it would likely become the dominant European power. Gorbachev wanted a gradual process of German integration but Kohl began calling for rapid reunification.[340] With Germany reunified, many observers declared the Cold War over.[341]

Presidency of the Soviet Union: 1990–1991

In February 1990, both liberalisers and Marxist-Leninist hardliners intensified their attacks on Gorbachev.[342] A liberalizer march took part in Moscow criticizing Communist Party rule,[343] while at a Central Committee meeting, the hardliner Vladimir Brovikov accused Gorbachev of reducing the country to "anarchy" and "ruin" and of pursuing Western approval at the expense of the Soviet Union and the Marxist-Leninist cause.[344] Gorbachev was aware that the Central Committee could still oust him as General Secretary, and so decided to reformulate the role of head of government to a presidency from which they could not remove him.[345] He decided that the presidential election should be held by the Congress of People's Deputies. He chose this over a public vote because he thought the latter would escalate tensions and feared that he might lose it;[346] a spring 1990 poll nevertheless still showed him as the most popular politician in the country.[347]

In March, the Congress of People's Deputies held the first (and only) Soviet presidential election, in which Gorbachev was the only candidate. He secured 1,329 in favor to 495 against; 313 votes were invalid or absent. He therefore became the first executive President of the Soviet Union.[348] A new 18-member Presidential Council de facto replaced the Politburo.[349] At the same Congress meeting, he presented the idea of repealing Article 6 of the Soviet constitution, which had ratified the Communist Party as the "ruling party" of the Soviet Union. The Congress passed the reform, undermining the de jure nature of the one-party state.[350]

In the 1990 elections for the Russian Supreme Soviet, the Communist Party faced challengers from an alliance of liberalisers known as "Democratic Russia"; the latter did particularly well in urban centers.[351] Yeltsin was elected the parliament's chair, something Gorbachev was unhappy about.[352] That year, opinion polls showed Yeltsin overtaking Gorbachev as the most popular politician in the Soviet Union.[347] Gorbachev struggled to understand Yeltsin's growing popularity, commenting: "he drinks like a fish... he's inarticulate, he comes up with the devil knows what, he's like a worn-out record."[353] The Russian Supreme Soviet was now out of Gorbachev's control;[353] in June 1990, it declared that in the Russian Republic, its laws took precedence over those of the Soviet central government.[354] Amid a growth in Russian nationalist sentiment, Gorbachev had reluctantly allowed the formation of a Communist Party of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic as a branch of the larger Soviet Communist Party. Gorbachev attended its first congress in June, but soon found it dominated by hardliners who opposed his reformist stance.[355]

German reunification and the Iraq War

In January 1990, Gorbachev privately agreed to permit East German reunification with West Germany, but rejected the idea that a unified Germany could retain West Germany's NATO membership.[356] His compromise that Germany might retain both NATO and Warsaw Pact memberships did not attract support.[357] In May 1990, he visited the U.S. for talks with President Bush;[358] there, he agreed that an independent Germany would have the right to choose its international alliances.[357] He later revealed that he had agreed to do so because U.S. Secretary of State James Baker promised that NATO troops would not be posted to eastern Germany and that the military alliance would not expand into Eastern Europe.[359] Privately, Bush ignored Baker's assurances and later pushed for NATO expansion.[360] On the trip, the U.S. informed Gorbachev of its evidence that the Soviet military—possibly unbeknownst to Gorbachev—had been pursuing a biological weapons program in contravention of the 1987 Biological Weapons Convention.[361] In July, Kohl visited Moscow and Gorbachev informed him that the Soviets would not oppose a reunified Germany being part of NATO.[362] Domestically, Gorbachev's critics accused him of betraying the national interest;[363] more broadly, they were angry that Gorbachev had allowed the Eastern Bloc to move away from direct Soviet influence.[364]

In August 1990, Saddam Hussein's Iraqi government invaded Kuwait; Gorbachev endorsed President Bush's condemnation of it. This brought criticism from many in the Soviet state apparatus, who saw Hussein as a key ally in the Persian Gulf and feared for the safety of the 9,000 Soviet citizens in Iraq, although Gorbachev argued that the Iraqis were the clear aggressors in the situation.[365] In November the Soviets endorsed a UN Resolution permitting force to be used in expelling the Iraqi Army from Kuwait.[366] Gorbachev later called it a "watershed" in world politics, "the first time the superpowers acted together in a regional crisis."[367] However, when the U.S. announced plans for a ground invasion, Gorbachev opposed it, urging instead a peaceful solution.[368] In October 1990, Gorbachev was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize; he was flattered but acknowledged "mixed feelings" about the accolade.[369] Polls indicated that 90% of Soviet citizens disapproved of the award, which was widely seen as a Western and anti-Soviet accolade.[370]

With the Soviet budget deficit climbing and no domestic money markets to provide the state with loans, Gorbachev looked elsewhere.[371] Throughout 1991, Gorbachev requested sizable loans from Western countries and Japan, hoping to keep the Soviet economy afloat and ensure the success of perestroika.[372] Although the Soviet Union had been excluded from the G7, Gorbachev secured an invitation to its London summit in July 1991.[373] There, he continued to call for financial assistance; Mitterrand and Kohl backed him,[374] while Thatcher—no longer in office— also urged Western leaders to agree.[375] Most G7 members were reluctant, instead offering technical assistance and proposing the Soviets receive "special associate" status—rather than full membership—of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund.[376] Gorbachev was frustrated that the U.S. would spend $100 billion on the Gulf War but would not offer his country loans.[377] Other countries were more forthcoming; West Germany had given the Soviets DM60 billion by mid-1991.[378] Later that month, Bush visited Moscow, where he and Gorbachev signed the START I treaty, a bilateral agreement on the reduction and limitation of strategic offensive arms, after ten years of negotiation.[379]

August putsch and government crises

At the 28th Communist Party Congress in July 1990, hardliners criticized the reformists but Gorbachev was re-elected party leader with the support of three-quarters of delegates and his choice of Deputy General Secretary, Vladimir Ivashko, was also elected.[380] Seeking compromise with the liberalizers, Gorbachev assembled a team of both his own and Yeltsin's advisers to come up with an economic reform package: the result was the "500 Days" programme. This called for further decentralization and some privatization.[381] Gorbachev described the plan as "modern socialism" rather than a return to capitalism but had many doubts about it.[382] In September, Yeltsin presented the plan to the Russian Supreme Soviet, which backed it.[383] Many in the Communist Party and state apparatus warned against it, arguing that it would create marketplace chaos, rampant inflation, and unprecedented levels of unemployment.[384] The 500 Days plan was abandoned.[385] At this, Yeltsin rallied against Gorbachev in an October speech, claiming that Russia would no longer accept a subordinate position to the Soviet government.[386]

By mid-November 1990, much of the press was calling for Gorbachev to resign and predicting civil war.[387] Hardliners were urging Gorbachev to disband the presidential council and arrest vocal liberals in the media.[388] In November, he addressed the Supreme Soviet where he announced an eight-point program, which included governmental reforms, among them the abolition of the presidential council.[389] By this point, Gorbachev was isolated from many of his former close allies and aides.[390] Yakovlev had moved out of his inner circle and Shevardnadze had resigned.[391] His support among the intelligentsia was declining,[392] and by the end of 1990 his approval ratings had plummeted.[393]

Amid growing dissent in the Baltics, especially Lithuania, in January 1991 Gorbachev demanded that the Lithuanian Supreme Council rescind its pro-independence reforms.[394] Soviet troops occupied several Vilnius buildings and clashed with protesters, 15 of whom were killed.[395] Gorbachev was widely blamed by liberalizers, with Yeltsin calling for his resignation.[396] Gorbachev denied sanctioning the military operation, although some in the military claimed that he had; the truth of the matter was never clearly established.[397] Fearing more civil disturbances, that month Gorbachev banned demonstrations and ordered troops to patrol Soviet cities alongside the police. This further alienated the liberalizers but was not enough to win-over hardliners.[398] Wanting to preserve the Union, in April Gorbachev and the leaders of nine Soviet republics jointly pledged to prepare a treaty that would renew the federation under a new constitution; six of the republics—Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, Georgia, and Armenia—did not endorse this.[399] A referendum on the issue brought 76.4% in favor of continued federation but the six rebellious republics had not taken part.[400] Negotiations as to what form the new constitution would take took place, again bringing together Gorbachev and Yeltsin in discussion; it was planned to be formally signed in August.[401]

In August, Gorbachev and his family holidayed at their dacha, "Zarya" ('Dawn') in Foros, Crimea.[402] Two weeks into his holiday, a group of senior Communist Party figures—the "Gang of Eight"—calling themselves the State Committee on the State of Emergency launched a coup d'état to seize control of the Soviet Union.[403] The phone lines to his dacha were cut and a group arrived, including Boldin, Shenin, Baklanov, and General Varennikov, informing him of the take-over.[404] The coup leaders demanded that Gorbachev formally declare a state of emergency in the country, but he refused.[405] Gorbachev and his family were kept under house arrest in their dacha.[406] The coup plotters publicly announced that Gorbachev was ill and thus Vice President Yanayev would take charge of the country.[407]

Yeltsin, now President of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, went inside the Moscow White House. Tens of thousands of protesters amassed outside it to prevent troops storming the building to arrest him.[408] Gorbachev feared that the coup plotters would order him killed, so had his guards barricade his dacha.[409] However, the coup's leaders realized that they lacked sufficient support and ended their efforts. On 21 August, Vladimir Kryuchkov, Dmitry Yazov, Oleg Baklanov, and Anatoly Lukyanov, and Vladimir Ivashko arrived at Gorbachev's dacha to inform him that they were doing so.[409]

That evening, Gorbachev returned to Moscow, where he thanked Yeltsin and the protesters for helping to undermine the coup.[410] At a subsequent press conference, he pledged to reform the Soviet Communist Party.[411] Two days later, he resigned as its General Secretary and called on the Central Committee to disband.[412] Several members of the coup committed suicide; others were fired.[413] Gorbachev attended a session of the Russian Supreme Soviet on 23 August, where Yeltsin aggressively criticized him for having appointed and promoted many of the coup members to start with. Yeltsin then announced a ban on the Russian Communist Party.[414]

Final collapse

On August 29, the Supreme Soviet indefinitely suspended all Communist Party activity, effectively ending Communist rule in the Soviet Union. From then on, the Soviet Union collapsed with dramatic speed. By the end of September, Gorbachev had lost the ability to influence events outside of Moscow.

On 30 October, Gorbachev attended a conference in Madrid trying to revive the Israeli–Palestinian peace process. The event was co-sponsored by the U.S. and Soviet Union, one of the first examples of such cooperation between the two countries. There, he again met with Bush.[415] En route home, he traveled to France where he stayed with Mitterrand at the latter's home near Bayonne.[416]

After the coup, Yeltsin had suspended all Communist Party activities on Russian soil by shutting down the Central Committee offices in Staraya Square along with raising of the imperial Russian tricolor flag alongside the Soviet flag at Red Square. By the final weeks of 1991, Yeltsin began to take over the remnants of the Soviet government including the Kremlin itself.

To keep unity within the country, Gorbachev continued to pursue plans for a new union treaty but found increasing opposition to the idea of a continued federal state as the leaders of various Soviet republics bowed to growing nationalist pressure.[417] Yeltsin stated that he would veto any idea of a unified state, instead favoring a confederation with little central authority.[418] Only the leaders of the Kazakhstan and Kirghizia supported Gorbachev's approach.[419] The referendum in Ukraine on 1 December with a 90% turnout for secession from the Union was a fatal blow; Gorbachev had expected Ukrainians to reject independence.[420]

Without Gorbachev's knowledge, Yeltsin met with Ukrainian President Leonid Kravchuk and Belarusian President Stanislav Shushkevich in Belovezha Forest, near Brest, Belarus, on 8 December and signed the Belavezha Accords, which declared the Soviet Union had ceased to exist and formed the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) as its successor.[421] Gorbachev only learned of this development when Shushkevich phoned him; Gorbachev was furious.[422] He desperately looked for an opportunity to preserve the Soviet Union, hoping in vain that the media and intelligentsia might rally against the idea of its dissolution.[423] Ukrainian, Belarusian, and Russian Supreme Soviets then ratified the establishment of the CIS.[424] On 10 December, he issued a statement calling the CIS agreement "illegal and dangerous".[425] On 20 December, the leaders of 11 of the 12 remaining republics–all except Georgia–met in Alma-Ata and signed the Alma-Ata Protocol, agreeing to dismantle the Soviet Union and formally establish the CIS. They also provisionally accepted Gorbachev's resignation as president of what remained of the Soviet Union. Gorbachev revealed that he would resign as soon as he saw that the CIS was a reality.[426][427]

Accepting the fait accompli of the Soviet Union's dissolution, Gorbachev reached a deal with Yeltsin that called for Gorbachev to formally announce his resignation as Soviet President and Commander-in-Chief on 25 December, before vacating the Kremlin by 29 December.[428] Yakovlev, Chernyaev, and Shevardnadze joined Gorbachev to help him write a resignation speech.[426] Gorbachev then gave his speech in the Kremlin in front of television cameras, allowing for international broadcast.[429] In it, he announced, "I hereby discontinue my activities at the post of President of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics." He expressed regret for the breakup of the Soviet Union but cited what he saw as the achievements of his administration: political and religious freedom, the end of totalitarianism, the introduction of democracy and a market economy, and an end to the arms race and Cold War.[430] Gorbachev was only the third Soviet leader, after Malenkov and Khrushchev, not to die in office.[431][432] The following day, 26 December, the Council of the Republics, the upper house of the Supreme Soviet, formally voted the Soviet Union out of existence.[433] The Soviet Union officially ceased to exist at midnight on 31 December 1991;[434] as of that date, all Soviet institutions that had not been taken over by Russia ceased to function.

Post-presidency

Initial years: 1991–1999

Out of office, Gorbachev had more time to spend with his wife and family.[435] He and Raisa initially lived in their dilapidated dacha on Rublevskoe Shosse, although were also allowed to privatize their small apartment on Kosygin Street.[435] He focused on establishing his International Foundation for Socio-Economic and Political Studies, or "Gorbachev Foundation", launched in March 1992;[436] Yakovlev and Grigory Revenko were its first Vice Presidents.[437] Its initial tasks were in analyzing and publishing material on the history of perestroika, as well as defending the policy from what it called "slander and falsifications". The foundation also tasked itself with monitoring and critiquing life in post-Soviet Russia and presenting alternate forms of development to those pursued by Yeltsin.[437] In 1993, Gorbachev launched Green Cross International, which focused on encouraging sustainable futures, and then the World Political Forum.[438]

To finance his foundation, Gorbachev began lecturing internationally, charging large fees to do so.[437] On a visit to Japan, he was well received and given multiple honorary degrees.[439] In 1992, he toured the U.S. in a Forbes private jet to raise money for his foundation. During the trip he met up with the Reagans for a social visit.[439] From there he went to Spain, where he attended the Expo '92 world fair in Seville and also met with Prime Minister Felipe González, who had become a friend of his.[440] In March, he visited Germany, where he was received warmly by many politicians who praised his role in facilitating German reunification.[441] To supplement his lecture fees and book sales, Gorbachev appeared in print and television adverts for companies like Pizza Hut and Louis Vuitton, enabling him to keep the foundation afloat.[442][443] With his wife's assistance, Gorbachev worked on his memoirs, which were published in Russian in 1995 and in English the following year.[444] He also began writing a monthly syndicated column for The New York Times.[445]