Naxalite

A Naxal or Naxalite (/ˈnʌksəlaɪt/)[1] is a member of any political organisation that claims the legacy of the Communist Party of India (Marxist–Leninist), founded in Calcutta in 1969. The Communist Party of India (Maoist) is the largest existing political group in that lineage today in India.[2]

| Part of a series on |

| Maoism |

|---|

|

|

People

|

|

Theoretical works |

|

History

|

|

Related topics |

|

The term Naxal derives from the name of the village Naxalbari in West Bengal, where the Naxalite peasant revolt took place in 1967. Naxalites are considered far-left communists, supportive of Maoism. Their origin can be traced to the split in 1967 of the Communist Party of India (Marxist) following the Naxalbari peasant uprising, leading to the formation of the Communist Party of India (Marxist–Leninist) two years later. Initially, the movement had its epicentre in West Bengal. In later years, it spread to less developed areas of rural southern and eastern India, such as Chhattisgarh, Odisha, Andhra Pradesh and Telangana through the activities of underground groups like the Communist Party of India (Maoist).[3] Some Naxalite groups have become legal organisations participating in parliamentary elections, such as the Communist Party of India (Marxist–Leninist) Liberation and the Communist Party of India (Marxist–Leninist) Janashakti.

History

The term Naxalites comes from Naxalbari, a small village in West Bengal, where a section of the Communist Party of India (Marxist) (CPI-M) led by Charu Majumdar, Kanu Sanyal, and Jangal Santhal initiated an uprising in 1967. However, the uprising itself formed after two decades of minor communist activity which first began in South India. In current-day Telangana, an Indian state which split from the larger Andhra Pradesh, communism began to manifest, and in July of 1948, a major event known as the Telangana Struggle occurred in which the lower-classes of 2,500 villages of the former Hyderabad State formed a series of communes.[4]Furthermore, in same year, far-leftist mentality was solidified within the government structure by the publication of two major communist documents.. The first, the Andhra Thesis, expressed "that 'Indian revolution' follow the Chinese path of protracted people's war" and how the "Indian revolution" must be similar to the Chinese people's war, in which the entirety of the population from the rural and agrarian areas of the nation should participate in conflict.[5] The second document would be the Andhra Letter which was published in June of 1948, and the letter spoke of how Mao Zedong's concept of New Democracy should be implemented in an Indian revolution.[6] In terms of communists in the young nation, the Communist Party of India (CPI) formed in 1920 had internal conflict because the CPI had support from the Soviets, and by 1964, the Communist Part of India (Marxist) was established.[7] From the Telangana Struggle and the two political manifestos, the Naxalites were not the first instance of communist activity in the newly-formed country.

On 18 May 1967, the Siliguri Kishan Sabha, of which Jangal was the president, declared their support for the movement initiated by Kanu Sanyal, and their readiness to adopt armed struggle to redistribute land to the landless.[8] The following week, a sharecropper near Naxalbari village was attacked by the landlord's men over a land dispute. On 24 May, when a police team arrived to arrest the peasant leaders, it was ambushed by a group of tribals led by Jangal Santhal, and a police inspector was killed in a hail of arrows. This event encouraged many Santhal tribals and other poor people to join the movement and to start attacking local landlords.[9]

These conflicts go back to the failure to implement the 5th and 6th Schedules of the Constitution of India.[10] In theory these Schedules provide for a limited form of tribal autonomy with regard to exploiting natural resources on their lands, e.g. pharmaceutical and mining, and 'land ceiling laws', limiting the land to be possessed by landlords and distribution of excess land to landless farmers and labourers.

Mao Zedong provided ideological leadership for the Naxalbari movement, advocating that Indian peasants and lower class tribals overthrow the government of the upper classes by force. From 1965-1966, the Communist Party of India (Marxist) had a major figure by the name of Charu Majumdar, and he was a major figure of the movement who believed in Zedong's "protracted people's war" ideology.[11][12] A large number of urban elites were also attracted to the ideology, which spread through Charu Majumdar's writings, particularly the 'Historic Eight Documents' which formed the basis of Naxalite ideology.[13] These documents were essays formed from the opinions of communist leaders and theorists such as Mao Zedong, Karl Marx, and Vladimir Lenin.[14] Using People's courts, similar to those established by Mao, Naxalites try opponents and execute with axes or knives, beat, or permanently exile them.[15]

At the time, the leaders of this revolt were members of the CPI (M), which joined a coalition government in West Bengal just a few months back. However, this plan of action led to dispute within the party as Charu Majumdar believed the CPM was to support a doctrine based on revolution similar to that of the People's Republic of China.[16][17] Leaders like land minister Hare Krishna Konar had been until recently "trumpeting revolutionary rhetoric, suggesting that militant confiscation of land was integral to the party's programme."[18] However, now that they were in power, CPI (M) did not approve of the armed uprising, and all the leaders and a number of Calcutta sympathisers were expelled from the party. This disagreement within the party soon culminated with the Naxalbari Uprising on May 25th of the same year, and Majumdar led a group of dissidents to start a revolt in the West Bengal village of Naxalbari.[19] The uprising occurred because an individual who was of tribal background (Adhivasi) was attacked by a group of people who acted on the orders of the local landlords, and this caused other Adhivasis in the area to retake their land, and after seventy-two days of revolt the CPI (M) coalition government suppressed this incident.[20]

Subsequently, In November 1967, this group, led by Sushital Ray Chowdhury, organised the All India Coordination Committee of Communist Revolutionaries (AICCCR).[21] Violent uprisings were organised in several parts of the country. On 22 April 1969 (Lenin's birthday), the AICCCR gave birth to the Communist Party of India (Marxist–Leninist) (CPI (ML)).

Practically all Naxalite groups trace their origin to the CPI (ML). A separate offshoot from the beginning was the Maoist Communist Centre, which evolved out of the Dakshin Desh group. The MCC later fused with the People's War Group to form the Communist Party of India (Maoist). A third offshoot was that of the Andhra revolutionary communists, mainly represented by the UCCRI(ML), following the mass line legacy of T. Nagi Reddy, which broke with the AICCCR at an early stage.

The early 1970s saw the spread of Naxalism to almost every state in India, barring Western India.[22] During the 1970s, the movement was fragmented into disputing factions. By 1980, it was estimated that around 30 Naxalite groups were active, with a combined membership of 30,000.[23]

Violence in West Bengal

Around 1971 the Naxalites gained a strong presence among the radical sections of the student movement in Calcutta.[24] Students left school to join the Naxalites. Majumdar, to entice more students into his organisation, declared that revolutionary warfare was to take place not only in the rural areas as before, but now everywhere and spontaneously. Thus Majumdar declared an "annihilation line", a dictum that Naxalites should assassinate individual "class enemies" (such as landlords, businessmen, university teachers, police officers, politicians of the right and left) and others.[25][26]

The chief minister, Siddhartha Shankar Ray of the Congress Party, instituted strong counter-measures against the Naxalites. The West Bengal police fought back to stop the Naxalites. The house of Somen Mitra, the Congress MLA of Sealdah, was allegedly turned into a torture chamber where Naxals were incarcerated illegally by police and the Congress cadres. CPI-M cadres were also involved in the "state terror". After suffering losses and facing the public rejection of Majumdar's "annihilation line", the Naxalites alleged human rights violations by the West Bengal police, who responded that the state was effectively fighting a civil war and that democratic pleasantries had no place in a war, especially when the opponent did not fight within the norms of democracy and civility.[9]

Large sections of the Naxal movement began to question Majumdar's leadership. In 1971 the CPI(ML) was split, as Satyanarayan Singh revolted against Majumdar's leadership. In 1972 Majumdar was arrested by the police and died in Alipore Jail presumably as a result of torture. His death accelerated the fragmentation of the movement.

Operation Steeplechase

In July 1971, Indira Gandhi took advantage of President's rule to mobilise the Indian Army against the Naxalites and launched a colossal combined army and police counter-insurgency operation, termed "Operation Steeplechase," killing hundreds of Naxalites and imprisoning more than 20,000 suspects and cadres, including senior leaders.[27] The paramilitary forces and a brigade of para commandos also participated in Operation Steeplechase. The operation was choreographed in October 1969, and Lt. General J.F.R. Jacob was enjoined by Govind Narain, the Home Secretary of India, that "there should be no publicity and no records" and Jacob's request to receive the orders in writing was also denied by Sam Manekshaw.[28]

Active regions

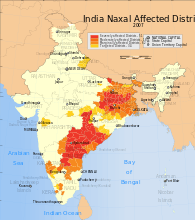

As of April 2018, the areas where Naxalites are most visible are:

- Andhra Pradesh: Visakhapatnam

- Bihar: Gaya, Jamui, Lakhisarai

- Chhattisgarh: Bastar, Bijapur, Dantewada, Kanker, Kondagaon, Narayanpur, Rajnandgaon, Sukma

- Jharkhand: Bokaro, Chatra, Garhwa, Giridih, Gumla, Hazaribagh, Khunti, Latehar, Lohardaga, Palamu, Ranchi, Simdega West, Singhbhum

- Maharashtra: Gadchiroli, Gondia, Yavatmal

- Odisha: Koraput, Malkangiri

- Telangana: Bhadradri, Kothagudem[29]

Situation during 2000–2011

Between 2002 and 2006, over three thousand people had been killed in Naxalite-Government conflicts, and by 2009, the conflict had displaced 350,000 members of tribal groups from their ancestral lands.[30]

In 2006 India's intelligence agency, the Research and Analysis Wing, estimated that 20,000 armed-cadre Naxalites were operating in addition to 50,000 regular cadres.[31] Their growing influence prompted Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh to declare them to be the most serious internal threat to India's national security.[32] Naxalites, and other anti-government militants, are often referred to as "ultras".[33]

In February 2009, the Indian Central government announced a new nationwide initiative, to be called the "Integrated Action Plan" (IAP) for broad, co-ordinated operations aimed at dealing with the Naxalite problem in all affected states (namely Karnataka, Chhattisgarh, Odisha, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Maharashtra, Jharkhand, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, and West Bengal). Importantly, this plan included funding for grass-roots economic development projects in Naxalite-affected areas, as well as increased special police funding for better containment and reduction of Naxalite influence in these areas.[34][35]

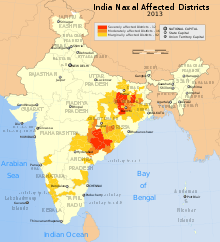

In 2009, Naxalites were active across approximately 180 districts in ten states of India.[36] In August 2010, after the first full year of implementation of the national IAP program, Karnataka was removed from the list of Naxalite-affected states.[37] In July 2011, the number of Naxalite-affected areas was reduced to 83 districts in nine states (including 20 additional districts).[38][39][40] In December 2011, the national government reported that the number of Naxalite-related deaths and injuries nationwide had gone down by nearly 50% from 2010 levels.[41] Maoist communist groups claimed responsibility for 123 deaths in 2013, which was nearly half of all deaths from terrorism in India.[42] The movement is described as "terrorist" by the Indian authorities but it is however popular in the regions where it is present. According to a study of the newspaper The Times of India 58% of people surveyed in the state of Andhra Pradesh, had a positive perception of the guerrillas, 19% against them.[43]

In a 2004 Indian Home Ministry estimate, their numbers were placed at that time at "9,300 hardcore underground cadre ... [holding] around 6,500 regular weapons beside a large number of unlicensed country-made arms".[44] In 2006, according to Judith Vidal-Hall, "Figures (in that year) put the strength of the movement at 15,000, and claim the guerrillas control an estimated one fifth of India's forests, as well as being active in 160 of the country's 604 administrative districts."[45] India's Research and Analysis Wing believed in 2006 that 20,000 Naxals were involved in the growing insurgency.[31]

Situation post 2010

2010

- 6 April: Naxalites launched the most deadly assault in the history of the Naxalite movement by killing 76 security personnel. The attack was launched by up to 1,000 Naxalites[46][47] in a well-planned attack, killing an estimated 76 CRPF personnel in two separate ambushes and wounding 50 others, in the remote jungles of Chhattisgarh's Dantewada district in Eastern/Central India.

- 17 May, Naxals blew up a bus on Dantewda–Sukhma road in Chhattisgarh, killing 15 policemen and 20 civilians. In the third major attack by Naxals on 29 June, at least 26 personnel of the CRPF were killed in Narayanpur district of Chhattisgarh.

Despite the 2010 Chhattisgarh ambushes, the most recent central government campaign to contain and reduce the militant Naxalite presence appears to be having some success.[41] States such as Madhya Pradesh have reported significant reduction in Naxalite activities as a result of their use of IAP funds for rural development within their states.[48] The recent success in containing violence may be due to a combination of more state presence, but also due to the recent introduction of social security schemes, such as NREGA.[49]

2011

- Late 2011:, Kishenji, the military leader of Communist Party of India (Maoist), was killed in an encounter with the joint operation forces, which was a huge blow to the Naxalite movement in eastern India.[50]

- March: Maoist rebels kidnapped two Italians in the eastern Indian state of Odisha, the first time Westerners were abducted there.[51]

- 27 March: 12 CRPF personnel were killed on in a landmine blast triggered by suspected Naxalites in Gadchiroli district of Maharashtra.[52]

2013

- 25 May 2013, Naxalites attacked a rally led by the Indian National Congress in Sukma village in Bastar Chhattisgarh, killing about 29 people. They killed senior party leader Mahendra Karma and Nand Kumar Patel and his son while in the attack another senior party leader Vidya Charan Shukla was severely wounded and later succumbed to death due to his injuries

- 11 June. See: 2013 Maoist attack in Darbha Valley.[53]

2014

2015

- 11 April 2015 : 7 Special Task Force (STF) personnel were killed in a Maoist ambush near Kankerlanka, Sukma, *Chhattisgarh.[74]

- 12 April 2015 : 1 BSF Jawan was killed in a Maoist attack near Bande, Kanker, Chhattisgarh.[75]

- 13 April 2015 : 5 Chhattisgarh Armed Force (CAF) Jawans were killed in a Maoist ambush near Kirandul, Dantewada, Chhattisgarh.[76]

2016

- 24 October 2016 : 24 Naxalites were killed by Andhra Pradesh Greyhounds forces in encounter that took place in the cut-off area of remote Chitrakonda on Andhra-Odisha border.[56]

- In November, 2016, three Naxalites were killed near Karulai in an encounter with Kerala police. Naxalite leader Kappu Devaraj from Andhra Pradesh is included in the list of killed in the incident.[57]

- Late November: In Jharkhand, six Naxalites were killed in a gun battle with Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) commandos. The CRPF recovered 600 bullets of various calibre, about 12 IEDs, an INSAS rifle, an SLR, a carbine and three other guns.[58]

2017

- 24 April 2017: In the 2017 edelbeda attack twenty five CRPF officers were killed in encounter with 300 Naxals. The encounter with 74 battalion of CRPF was reported from Kala Pathar near Chintagufa in Sukma District of Chhattisgarh.[59]

2018

- 13 March 2018: 2018 Sukma attack - 9 CRPF personnel were killed and two injured after a powerful IED blast that destroyed their mine-protected vehicle in Sukma, Chhattisgarh.[60]

- 22 March 2018: At least 37 Naxalites were killed by police in a four-hour gun battle on the border between Maharashtra and Chhattisgarh.[61]

2019

- 8 March 2019 - 1 Naxal leader was killed in an encounter with the Kerala police at a Wayanad resort.[62]

- 1 May 2019 - 15 Indian commandos and driver killed in Maoist attack - Gadchiroli.[63]

- 28 October 2019- Kerala Police's elite commando team "Thunderbolt" gunned down 3 maoists in an encounter in the Attappadi hills region of Palakkad. One remaining member of the maoists group was killed a day later when the police team went to inspect the encounter site, following an attack on the team.[64]

- 23 November 2019 - Naxals opened fire on a patrol van killing an ASI and three home guard Jawans in Latehar, Jharkhand.

Causes

According to Maoist sympathisers, the Indian Constitution "ratified colonial policy and made the state custodian of tribal homelands", turning tribal populations into squatters on their own land and denied them their traditional rights to forest produce.[65] These Naxalite conflicts began in the late 1960s with the prolonged failure of the Indian government to implement constitutional reforms to provide for limited tribal autonomy with respect to natural resources on their lands, e.g. pharmaceutical and mining, as well as pass 'land ceiling laws', limiting the land to be possessed by landlords and distribution of excess land to landless farmers and labourers.[66] In Scheduled Tribes [ST] areas, disputes related to illegal alienation of ST land to non-tribal people, still common, gave rise to the Naxalite movement.[30]

Tribal participation in Naxalite movements

Tribal communities are likely to participate in Naxalism to push back against structural violence by the state, including land theft for purposes of mineral extraction.[67] Impoverished areas with no electricity, running water, or healthcare provided by the state may accept social services from Naxalite groups, and give their support to the Naxal cause in return.[68] Some argue that the state's absence allowed for Naxalites to become the legitimate authority in these areas by performing state-like functions, including enacting policies of redistribution and building infrastructure for irrigation.[69] Healthcare initiatives such as malaria vaccination drives and medical units in areas without doctors or hospitals have also been documented.[70][71] Although Naxalite groups engage in coercion to grow membership, the Adivasi experience of poverty, when contrasted with the state's economic growth, can create an appeal for Naxal ideology and incentivize tribal communities to join Naxal movements out of "moral solidarity".[72]

Recruitment and financial base

In terms of recruitment, the Naxalites focus heavily on the idea of a revolutionary personality, and in the early years of the movement, Charu Majumdar expressed how this type of persona is necessary for maintaining and establishing loyalty among the Naxalites.[73] According to Majumdar, he believed the essential characteristics of a recruit must be selflessness and the ability to self-sacrifice, and in order to produce such a specific personality, the organization began to recruit students and youth.[74] In addition to entrenching loyalty and a revolutionary personality within these new insurgents, Naxalites chose the youth due to other factors. The organization selected the youth because these students represented the educated section of Indian society, and the Naxalites felt it necessary to include educated insurgents because these recruits would then be crucial in the duty of spreading the communist teachings of Mao Zedong.[75] In order to expand their base, the movement relied on these students to spread communist philosophy to the uneducated rural and working class communities.[76] Majumdar believed it necessary to recruit students and youth who were able to integrate themselves with the peasantry and working classes, and by living and working in similar conditions to these lower-class communities, the recruits are able to carry the communist teachings of Mao Zedong to villages and urban centers.[77]

The financial base of the Naxalites is diverse because the organization finances itself from a series of sources. The mining industry is known to be a profitable financial source for the Naxalites, as they tend to extort about 3% of the profits from each mining company that operates in the areas under Naxal control.[78] In order to continue mining operations, these firms also pay the Naxalites for "protection" services which allows miners to work without having to worry about Naxalite attacks.[79] The organization also funds itself through the drug trade, where it cultivates drugs in areas of Orissa, Andhra Pradesh, Jharkhand, and Bihar.[80] Drugs such as marijuana and opium are distributed throughout the country by middlemen who work on behalf of the Naxalites.[81] The drug trade is extremely profitable for the movement, as about 40% of Naxal funding comes through the cultivation and distribution of opium.[82]

See also

- Marxism–Leninism

- Red Corridor

- People's war

- Shramik Sangram Committee

References

- "Naxalite". Collins English Dictionary.

- "Naxalite | Indian communist groups". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- Ramakrishnan, Venkitesh (21 September 2005). "The Naxalite Challenge". Frontline Magazine (The Hindu). Archived from the original on 17 October 2006. Retrieved 15 March 2007.

- "History of Naxalism". Hindustan Times. 9 May 2003. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- "History of Naxalism". Hindustan Times. 9 May 2003. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- "History of Naxalism". Hindustan Times. 9 May 2003. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- Roy, Siddharthya. "Half a Century of India's Maoist Insurgency". thediplomat.com. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- Sen, Sunil Kumar (1982). Peasant movements in India: mid-nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Calcutta: K.P. Bagchi.

- Diwanji, A. K. (2 October 2003). "Primer: Who are the Naxalites?". Rediff.com. Retrieved 15 March 2007.

- See Outlook India comment by E.N. Rammohan 'Unleash the Good Force' – edition 16 July 2012.

- "History of Naxalism | india | Hindustan Times". 22 February 2018. Archived from the original on 22 February 2018. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- Roy, Siddharthya. "Half a Century of India's Maoist Insurgency". thediplomat.com. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- "History of Naxalism". Hindustan Times. 15 December 2005. Archived from the original on 8 February 2011.

- "History of Naxalism | india | Hindustan Times". 22 February 2018. Archived from the original on 22 February 2018. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- Loyd, Anthony (2015). "India's insurgency". National Geographic (April): 82–94. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- "History of Naxalism | india | Hindustan Times". 22 February 2018. Archived from the original on 22 February 2018. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- Roy, Siddharthya. "Half a Century of India's Maoist Insurgency". thediplomat.com. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- Atul Kohli (1998). From breakdown to order: West Bengal, in Partha Chatterjee, State and politics in India. OUP. ISBN 0-19-564765-3.p. 348

- "History of Naxalism | india | Hindustan Times". 22 February 2018. Archived from the original on 22 February 2018. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- "History of Naxalism | india | Hindustan Times". 22 February 2018. Archived from the original on 22 February 2018. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- Mukherjee, Arun (2007). Maoist "spring thunder": the Naxalite movement 1967–1972. K.P. Bagchi & Co., Calcutta. ISBN 978-81-7074-303-3.p.295

- "Naxalite violence continues in Calcutta". The Indian Express. 22 August 1970. p. 7. Retrieved 10 April 2017.

- Singh, Prakash. The Naxalite Movement in India. New Delhi: Rupa & Co., 1999. p. 101.

- Judith Vidal-Hall, "Naxalites", p. 73–75 in Index on Censorship, Volume 35, Number 4 (2006). p. 73.

- Sen, Antara Dev (25 March 2010). "A true leader of the unwashed masses". DNA (Diligent Media Corporation). Mumbai, India. Archived from the original on 7 January 2014.

- Dasgupta, Biplab (1973). "Naxalite Armed Struggles and the Annihilation Campaign in Rural Areas" (PDF). Economic and Political Weekly. 1973: 173–188. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 November 2011.

- Lawoti, Mahendra; Pahari, Anup Kumar (2009). "Part V: Military and state dimension". The Maoist Insurgency in Nepal: Revolution in the Twenty-first Century. London: Routledge. p. 208. ISBN 978-1-135-26168-9.

The second turning point came in the wake of the 1971 Bangladesh war of independence which India supported with armed troops. With large contingents of Indian Army troops amassed in the West Bengal border with what was then East Pakistan, the Government of Indira Gandhi used the opening provided by President's Rule to divert sections of the army to assist the police in decisive counter–insurgency drives across Naxal–impacted areas. "Operation Steeplechase," a police and army joint anti–Naxalite undertaking, was launched in July–August 1971. By the end of "Operation Steeplechase" over 20,000 suspected Naxalites were imprisoned and including senior leaders and cadre, and hundreds had been killed in police encounters. It was a massive counter–insurgency undertaking by any standards.

- Pandita, Rahul (2011). Hello, Bastar : The Untold Story of India's Maoist Movement. Chennai: Westland (Tranquebar Press). pp. 23–24. ISBN 978-93-80658-34-6. OCLC 754482226.

Meanwhile, the Congress government led by Indira Gandhi decided to send in the army and tackle the problem militarily. A combined operation called Operation Steeplechase was launched jointly by military, paramilitary and state police forces in West Bengal, Bihar and Orissa.

In Kolkata, Lt General J.F.R. Jacob of the Indian Army's Eastern Command received two very important visitors in his office in October 1969. One was the army chief General Sam Manekshaw and the other was the home secretary Govind Narain. Jacob was told of the Centre's plan to send in the army to break the Naxal. More than 40 years later, Jacob would recall how he had asked for more troops, some of which he got along with a brigade of para commandos. When he asked his boss to give him something in writing, Manekshaw declined, saying, 'Nothing in writing.' while secretary Narain added that there should be no publicity and no records. - "The contours of the new Red map". The Indian Express. 17 April 2018. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- Pike, John (2 February 2017). "Naxalite". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

In India today there are many Maoist parties and organisations that either predate the Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) or emerged from factions when the CPI-ML split after the death of Charu Majumdar.

- Philip Bowring (18 April 2006). "Maoists who menace India". International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 17 March 2009.

- "South Asia | Senior Maoist 'arrested' in India". BBC News. 19 December 2007. Archived from the original on 20 December 2007.

- Press Trust of India (PTI) (25 March 2006). "Naxals attack Orissa jail, free prisoners, kill 3 cops". Indian Express. Archived from the original on 7 January 2014.

- "Special project for Naxal areas to be extended to 18 more districts". The Times Of India. 8 December 2011. Retrieved 2 January 2012. Times of India describes some details of ongoing nationwide Naxalite containment program, India's "Integrated Action Plan".

- Co-ordinated operations to flush out Naxalites soon The Economic Times, 6 February 2009.

- Handoo, Ashok. "Naxal Problem needs a holistic approach". Press Information Bureau. Archived from the original on 8 September 2009. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

- "Karnataka no longer Naxal infested". The Times Of India. 26 August 2010.

- Chhibber, Maneesh (5 June 2011). "Centre to declare more districts Naxal-hit". Indian Express. Archived from the original on 16 December 2012.

- Ministry of Panchayati Raj (14 January 2011). "Sixty Tribal and Backward districts in 9 states to get Central Grant under IAP". Press Information Bureau, Government of India. Archived from the original on 5 September 2012.

- Singh, Mahendra Kumar (23 June 2011). "Development plan for Naxal-hit districts shows good response". The Times Of India.

- "'Historic low' in terror, Naxal violence". 31 December 2012. Archived from the original on 19 June 2013. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

- "Terror activities rise in India by 70 per cent: Global Index". India News Analysis Opinions on Niti Central. Archived from the original on 24 January 2015.

- "58% in AP say Naxalism is good, finds TOI poll". The Times Of India. 28 September 2010. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- Quoted in Judith Vidal-Hall, "Naxalites", p. 73–75 in Index on Censorship, Volume 35, Number 4 (2006). p. 74.

- Judith Vidal-Hall, "Naxalites", p. 73–75 in Index on Censorship, Volume 35, Number 4 (2006). p. 74.

- "Indian police killed by Maoists". Al Jazeera. 6 April 2010. Archived from the original on 16 September 2012.

- "76 security men killed by Naxals in Chhattisgarh". Ndtv.com. 6 April 2010. Archived from the original on 9 April 2010.

- "MP govt claims positive change in Naxal-hit areas". 2011. Retrieved 2 January 2011.

- Fetzer, Thiemo (18 October 2013). "Can Workfare Programs Moderate Violence? Evidence from India" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 November 2013. Abstract

- Reddy, K. Srinivas (25 November 2011). "Kishenji's death a serious blow to Maoist movement". The Hindu. Chennai, India.

- "India Maoists kidnap Italian tourists in Orissa". BBC News. 18 March 2012.

- "12 CRPF jawans killed in Gadchiroli Naxal ambush". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 27 March 2012.

- "Naxalite attack: 2 Congress leaders massacred, Rahul Gandhi reaches Chhattisgarh". Dainik Bhaskar. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- Suvojit Bagchi. "Maoists kill 15 in Chhattisgarh". The Hindu.

- "Deadly Naxal attack in Chhattisgarh; 14 CRPF troopers dead, 12 injured". Zee News.

- "24 Maoists killed in encounter on Andhra-Odisha border". The Times of India. 24 October 2016. Retrieved 30 October 2016.

- "നിലമ്പൂര് ഏറ്റുമുട്ടല് : കൊല്ലപ്പെട്ടവരില് മാവോവാദി നേതാവും". www.mathrubhumi.com (in Malayalam). 24 November 2016. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- "6 Naxals killed in Jharkhand". The Hindu.

- "Naxal attack in Chhattisgarh's Sukma: How 300 Maoists attacked 99-member CRPF troop". Firstpost. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- "Watch Live : News of 8 soldiers martyr in encounter in Sukma Kistaram | Watch Live : सुकमा के किस्टारम में नक्सलियों ने उड़ाया एंडी लैंडमाइंस व्हीकल : 9 जवान शहीद, 2 घायल; देखें घटनास्थल की तस्वीरें". www.inhnews.in. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- Jadhav, Rajendra. "Police kill at least 37 Maoist militants in central India". TimesLIVE. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- Prashanth, M. P. (7 March 2019). "Maoist killed in police encounter inside Kerala resort". The Times of India. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- Rajput, Rashmi (1 May 2019). "Naxal attack in Gadchiroli leaves 11 security personnel dead". Retrieved 2 May 2019 – via The Economic Times.

- https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/kerala-police-thunderbolts-maoists-naxals-killed-attapadi-hills-palakkad-1613891-2019-10-29

- Roy, Arundhati (27 March 2010). "Gandhi, but with guns: Part One". www.theguardian.com. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- E.N. Rammohan (16 July 2012). "Unleash The Good Force". www.outlookindia.com. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- Shifting perspectives in tribal studies : from an anthropological approach to interdisciplinarity and consilience. Behera, M. C., 1959-. Singapore. 25 June 2019. ISBN 9789811380907. OCLC 1105928010.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Shah, Alpa (1 August 2013). "The intimacy of insurgency: beyond coercion, greed or grievance in Maoist India". Economy and Society. 42 (3): 480–506. doi:10.1080/03085147.2013.783662. ISSN 0308-5147.

- Walia, H.S. (25 April 2018). "The Naxal Quagmire in Bihar & Jharkhand – Genesis & Sustenance". Learning Community: An International Journal of Education and Social Development. 9 (1). doi:10.30954/2231-458X.01.2018.7.

- Santanama (2010). Jangalnama: Inside the Maoist Guerrilla Zone. New Delhi: Penguin. ISBN 9780143414452.

- Pandita, Rahul. (2011). Hello, Bastar : the untold story of India's Maoist movement. Chennai: Tranquebar Press. ISBN 978-9380658346. OCLC 754482226.

- Shah, Alpa (1 August 2013). "The intimacy of insurgency: beyond coercion, greed or grievance in Maoist India". Economy and Society. 42 (3): 480–506. doi:10.1080/03085147.2013.783662. ISSN 0308-5147.

- Dasgupta, Rajeshwari (2006). "UC Berkeley Library Proxy Login". Economic and Political Weekly. 41 (19): 1920–1927. JSTOR 4418215.

- Dasgupta, Rajeshwari (2006). "UC Berkeley Library Proxy Login". Economic and Political Weekly. 41 (19): 1920–1927. JSTOR 4418215.

- Dasgupta, Rajeshwari (2006). "UC Berkeley Library Proxy Login". Economic and Political Weekly. 41 (19): 1920–1927. JSTOR 4418215.

- Dasgupta, Rajeshwari (2006). "UC Berkeley Library Proxy Login". Economic and Political Weekly. 41 (19): 1920–1927. JSTOR 4418215.

- Dasgupta, Rajeshwari (2006). "UC Berkeley Library Proxy Login". Economic and Political Weekly. 41 (19): 1920–1927. JSTOR 4418215.

- Hoelscher, Kristian. "Hearts and Mines: A District-Level Analysis of the Maoist Conflict in India" (PDF).

- Hoelscher, Kristian. "Hearts and Mines: A District-Level Analysis of the Maoist Conflict in India" (PDF).

- Prakash, Om (2015). "UC Berkeley Library Proxy Login". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 76: 900–907. JSTOR 44156660.

- Prakash, Om (2015). "UC Berkeley Library Proxy Login". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 76: 900–907. JSTOR 44156660.

- Prakash, Om (2015). "UC Berkeley Library Proxy Login". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 76: 900–907. JSTOR 44156660.

Further reading

- "Urban Naxals" by Vivek Agnohotri, Publisher: Garuda Prakashan

- Naxalite Politics in India, by J. C. Johari, Institute of Constitutional and Parliamentary Studies, New Delhi, . Published by Research Publications, 1972.

- The Naxalite Movement, by Biplab Dasgupta. 1974.

- The Naxalite Movement: A Maoist Experiment, by Sankar Ghosh. Published by Firma K.L. Mukhopadhyay, 1975. ISBN 0-88386-568-8.

- The Naxalite Movement in India: Origin and Failure of the Maoist Revolutionary Strategy in West Bengal, 1967–1971, by Sohail Jawaid. Published by Associated Pub. House, 1979.

- In the Wake of Naxalbari: A History of the Naxalite Movement in India, by Sumanta Banerjee. Published by Subarnarekha, 1980.

- Edward Duyker Tribal Guerrillas: The Santals of West Bengal and the Naxalite Movement, Oxford University Press, New Delhi, 1987, p. 201, SBN 19 561938 2

- The Naxalite Movement in India, by Prakash Singh. Published by Rupa, 1995. ISBN 81-7167-294-9.

- V. R. Raghavan ed. The Naxal Threat : Causes, State Responses and Consequences, Publisher Vij Books India Pvt Ltd, ISBN 978-93-80177-77-9

- Mary Tyler (1977). My Years in an Indian Prison. London: Victor Gollancz Ltd. OCLC 3273743.

- Verghese, A. (2016). "British Rule and Tribal Revolts in India: The curious case of Bastar." Modern Asian Studies, 50(5), 1619-1644.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Naxalite. |

- Status Paper on the Naxalite problem – South Asia Terrorism Portal

- West Bengal, districts affected by Naxalite violence – South Asia Terrorism Portal

- Articles and Research Reports on Naxalite Violence in India and Pakistan

- "History of Naxalism". Hindustan Times. 15 December 2005. Archived from the original on 8 February 2011.