Operation Blacklist Forty

Operation Blacklist Forty[1] was the codename for the United States occupation of Korea between 1945 and 1948. Following the end of World War II, U.S. forces landed within the present-day South Korea to accept the surrender of the Japanese, and help create an independent and unified Korean government with the help of the Soviet Union, which occupied the present-day North Korea. However, when this effort proved unsuccessful, the United States and the Soviet Union both established their own friendly governments, resulting in the current division of the Korean Peninsula.[1][2]

| Operation Blacklist Forty | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Cold War | |

| |

| Location | |

| Objective | Occupation of Korea south of the 38th parallel |

| Date | 1945–1948 |

| Executed by | |

| Outcome | Successful operation

|

Background

The partition of Korea into occupation zones was proposed in August 1945, by the United States to the Soviet Union following the latter's entry in the war against Japan. The 38th parallel north was chosen to separate the two occupation zones on August 10 by two American officers, Dean Rusk and Charles Bonesteel, working on short notice and with little information on Korea. Their superiors endorsed the partition line and the proposal was accepted by the Soviets. The Americans hoped to establish a representative government supportive of American policy in the region, and the Soviets hoped to establish another communist nation friendly to their interests.[1][2][3]

Occupation

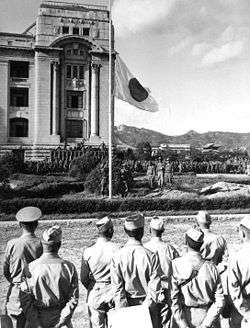

The American occupation force composed of 45,000 men from the United States Army's XXIV Corps. The first of the American forces to arrive in Korea was a small advanced party that landed at Kimpo Airfield near Seoul on September 4, 1945. Another small advanced party, consisting of fourteen men of the 7th Infantry Division, sailed into Inchon on September 8, and the main landing began on the following day. According to author Paul M. Edwards, the United States government had little interest in Korea, and relied on General Douglas MacArthur, who was in command of the occupation of Japan, to make most of the post-war decisions. MacArthur, however, was already "overloaded" with the work that needed to be done in Japan, so he ordered the commander of Operation Blacklist Forty, Lieutenant General John R. Hodge, to maintain a "harsh" occupation of Korea. Hodge set up his headquarters at the Banda Hotel in Seoul, established a military government, declared English to be the official language of Korea, and began the process of building an independent Korean government that was friendly to the United States.[1][2][3]

Hodge was considered a great battlefield commander, but a poor diplomat. There is little doubt he disliked Koreans, and was ignorant of their culture and how it differed from that of the Japanese. As a result, Hodge made many mistakes, including issuing an order to his men to "treat the Koreans as enemies." Furthermore, due to a shortage of manpower, Hodge allowed the old Japanese police force to remain on duty for crowd control and similar work. He also retained the colonial Japanese government, at least initially, until he could find suitable American replacements. However, following a complaint from the Korean people, the American military government in Tokyo officially had Korea removed from Japan's political and administrative control on October 2, 1945. Thus, the Japanese administrators were removed from power, although many were henceforth employed as advisors to their American replacements. Edwards says that General Hodge's most significant contribution to the occupation was the alignment of his military government with that of Korea's wealthy anti-Communist faction, and the promotion of men who had previously collaborated with the Japanese into positions of authority.[1][2][3]

Author E. Takemae says that the American forces were greeted as occupiers, and not as liberators. He also says that the Americans held the Japanese in higher regard than the Koreans, because of the former's military background, and appreciated Japanese knowledge and administrative skills, which they did not find among the Koreans. As it turned out, the Americans found that it was easier to deal with Japanese authorities in regards to the handling of Korea, instead of dealing directly with Korea's many different political factions. According to Takemae; "[I]n the eyes of many Koreans, the Americans were as bad as the Japanese."[3]

_off_the_Korean_coast%2C_28_September_1945.jpg)

Preparations for the withdrawal of American and Soviet forces from the Korean Peninsula could not begin until the United States and the Soviets could agree to establish a unified Korean government friendly to both nations' interests. However, the Soviets refused to accept any idea that did not involve the creation of a communist state, and therefore the negotiations were fruitless. As result of this disagreement, the United States sent the "Korean question" to the United Nations (UN). The UN agreed to take up the challenge in September 1947, and proceeded with providing the Koreans with UN-supervised elections. The Soviet Union, however, made it clear that any decision made by the UN would only apply to the portion of Korea south of the 38th parallel, and that anything north of the parallel would be determined by either itself or the new Democratic People's Republic of Korea (North Korea). Nevertheless, the elections were held, and the exiled Korean leader, Syngman Rhee, was inaugurated president of the new Republic of Korea (South Korea) on July 24, 1948.[1][4]

The American and Soviet occupations of Korean ended soon after, leaving the Korean peninsula divided. According to Edwards, most Americans were glad to be gone. By 1950, Korea, or Far Eastern affairs in general, had become of such small importance to the Americans that on January 5, 1950, President Harry Truman said that he would not intervene in the clash between the Chinese Communists and the Nationalists on Taiwan, or on the Chinese mainland, and seven days later Secretary of State Dean Acheson said that "Korea was now outside the American sphere of influence." Despite this, the United States and South Korea signed a military assistance pact on January 26, 1950, but only $1,000 worth of signal wire had arrived in country by the time of the outbreak of the Korean War on June 25, 1950.[1]

See also

References

- Edwards, Paul M. (2006). The Korean War. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0313332487.

- Edwards, Paul M. (2010). Combat operations of the Korean War: ground, air, sea, special and covert. McFarland. ISBN 0786458127.

- Takemae, E. (2003). The Allied Occupation of Japan. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 0826415210.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1965). The Oxford History of the American People. Oxford University Press.